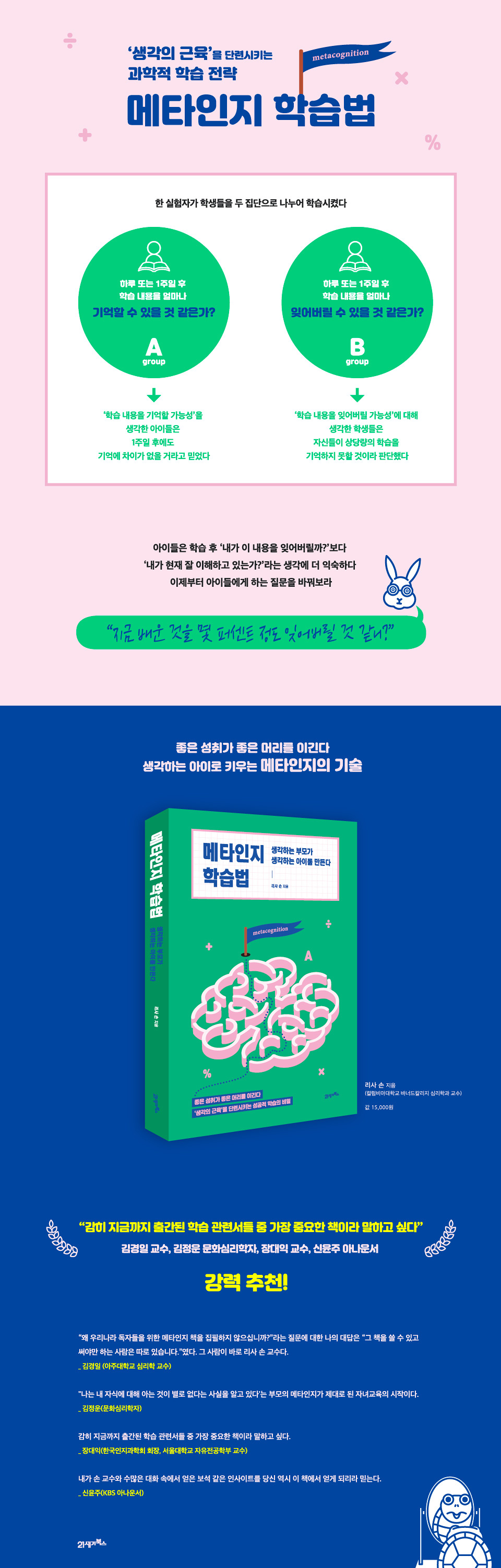

Metacognitive learning method

|

Description

Book Introduction

All learning begins with metacognition.

Do you remember the fable "The Tortoise and the Hare"? It's Aesop's fable about a race between a tortoise and a hare.

We already know that in the race between the tortoise and the hare, the tortoise won.

But strangely enough, many parents want their children to be rabbits.

Whether it's studying or arts and physical education, it means 'I just want the child to learn quickly.'

Reflecting this, in Korea, metacognition is known as the 'study method of the top 1%' or 'how to study well.'

Many parents view metacognition through a means-end framework, thinking that fostering metacognition will help their children "learn faster" or "get 100 on tests."

However, the real purpose of metacognition is to help us realize that the process of developing metacognition is the process of learning.

The metacognitive learning method presented by Professor Lisa Sohn, a professor of psychology at Barnard College, Columbia University and a leading expert in metacognitive psychology, provides much food for thought for parents who are only focused on speed and grades.

Based on numerous research results, it scientifically explains why children get different results even when studying for the same amount of time, what to look for when there is no change in a child's grades despite studying hard, and how to raise a child with strong 'power of thought = inner strength.'

Do you remember the fable "The Tortoise and the Hare"? It's Aesop's fable about a race between a tortoise and a hare.

We already know that in the race between the tortoise and the hare, the tortoise won.

But strangely enough, many parents want their children to be rabbits.

Whether it's studying or arts and physical education, it means 'I just want the child to learn quickly.'

Reflecting this, in Korea, metacognition is known as the 'study method of the top 1%' or 'how to study well.'

Many parents view metacognition through a means-end framework, thinking that fostering metacognition will help their children "learn faster" or "get 100 on tests."

However, the real purpose of metacognition is to help us realize that the process of developing metacognition is the process of learning.

The metacognitive learning method presented by Professor Lisa Sohn, a professor of psychology at Barnard College, Columbia University and a leading expert in metacognitive psychology, provides much food for thought for parents who are only focused on speed and grades.

Based on numerous research results, it scientifically explains why children get different results even when studying for the same amount of time, what to look for when there is no change in a child's grades despite studying hard, and how to raise a child with strong 'power of thought = inner strength.'

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Prologue | "Mom, but this isn't normal!"

Before we begin, all learning begins with metacognition.

Chapter 1: The First Illusion That Hinders Metacognition: Thinking the Fast Way Is Good

1 Are children who learn quickly smart?

2. The Trap of Overconfidence: “Mom Knows Best”

3. “I already knew it?” The fallacy of hindsight bias

4 The Swamp of Stereotypes That Threatens Children's Self-Confidence

5 How is anxiety learned?

6. Allow trial and error to become the foundation for growth.

7. “I’m afraid of not living up to expectations” Acquired Imposter Syndrome

8 Why results vary even when studying for the same amount of time

9. There is also a golden time for metacognition.

Chapter 2: The Second Illusion That Hinders Metacognition: Thinking the Easy Way Is Better

1 Short-term action strategies to achieve long-term goals

2 Understanding 'context' reveals metacognition.

3 What would you think?

4 The very dangerous illusion that you are learning well

5 Lightning Strike vs.

Distributed learning

6 Good achievements beat good heads.

7 What's Blocking Our Child's Metacognition?

Chapter 3: The Third Illusion That Hinders Metacognition: Thinking the Path Without Failure is Good

1 Do machines have metacognition?

2 A child's language ability is limitless.

3 Children who learn on their own even without the correct answer

4 “So what do you think?”

5 Ask not 'How much will I remember?' but 'How much will I forget?'

6. The pitfalls of multiple-choice tests that don't even give you time to think.

7 Rediscovering Mistakes, Rediscovering Experience

8 Secrets of Self-Study: Motivation

Chapter 4: Finding the Right Balance Between the Tortoise and the Hare

1 Why the Tortoise Participated in the Race with the Hare

2 Do you trust your child's choices?

3. Don't rush, but don't rest either: A parent's attitude toward dealing with impatience

4 Will learning metacognition improve my child's grades?

5 Even animals without language use metacognition.

6 Thinking Habits That Develop Creativity

Chapter 5 All change begins with 'knowing' myself.

1. The person who knows you best is you.

2 Parents' faith is the best reward.

3 The Power of Self-Confidence

4. Make your child a knowledge transmitter: Teaching training

5 Are you a parent who prioritizes your child's metacognition?

6 Without fear there is no courage.

7 Other people don't know my child's true abilities.

8 Ultimately, my child is the answer, the limits of privilege

Epilogue | To all the turtles of the world

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Glossary

References

Before we begin, all learning begins with metacognition.

Chapter 1: The First Illusion That Hinders Metacognition: Thinking the Fast Way Is Good

1 Are children who learn quickly smart?

2. The Trap of Overconfidence: “Mom Knows Best”

3. “I already knew it?” The fallacy of hindsight bias

4 The Swamp of Stereotypes That Threatens Children's Self-Confidence

5 How is anxiety learned?

6. Allow trial and error to become the foundation for growth.

7. “I’m afraid of not living up to expectations” Acquired Imposter Syndrome

8 Why results vary even when studying for the same amount of time

9. There is also a golden time for metacognition.

Chapter 2: The Second Illusion That Hinders Metacognition: Thinking the Easy Way Is Better

1 Short-term action strategies to achieve long-term goals

2 Understanding 'context' reveals metacognition.

3 What would you think?

4 The very dangerous illusion that you are learning well

5 Lightning Strike vs.

Distributed learning

6 Good achievements beat good heads.

7 What's Blocking Our Child's Metacognition?

Chapter 3: The Third Illusion That Hinders Metacognition: Thinking the Path Without Failure is Good

1 Do machines have metacognition?

2 A child's language ability is limitless.

3 Children who learn on their own even without the correct answer

4 “So what do you think?”

5 Ask not 'How much will I remember?' but 'How much will I forget?'

6. The pitfalls of multiple-choice tests that don't even give you time to think.

7 Rediscovering Mistakes, Rediscovering Experience

8 Secrets of Self-Study: Motivation

Chapter 4: Finding the Right Balance Between the Tortoise and the Hare

1 Why the Tortoise Participated in the Race with the Hare

2 Do you trust your child's choices?

3. Don't rush, but don't rest either: A parent's attitude toward dealing with impatience

4 Will learning metacognition improve my child's grades?

5 Even animals without language use metacognition.

6 Thinking Habits That Develop Creativity

Chapter 5 All change begins with 'knowing' myself.

1. The person who knows you best is you.

2 Parents' faith is the best reward.

3 The Power of Self-Confidence

4. Make your child a knowledge transmitter: Teaching training

5 Are you a parent who prioritizes your child's metacognition?

6 Without fear there is no courage.

7 Other people don't know my child's true abilities.

8 Ultimately, my child is the answer, the limits of privilege

Epilogue | To all the turtles of the world

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

Glossary

References

Detailed image

Into the book

Having any kind of stereotype is like creating a category about a certain type.

For example, if a child first sees a small, white animal and learns to call it a "puppy," he or she will also respond by calling a small, white cat a "puppy."

As this process is repeated, the categorization process also becomes faster.

Categorization plays a significant role in concept formation, and these categorization strategies become stereotypes through the brain's automatic processing (the unconscious judgment of information about an object).

--- From "The Swamp of Stereotypes That Threaten Children's Confidence"

Many children who fall into the metacognitive illusion suffer from the pressure of having to 'study for a long time'.

Due to the illusion of control, I am spending 3 hours studying when I should have finished in 30 minutes.

If you focus only on English and not on math because your English skills are lacking, you will end up failing both subjects.

Focusing all your energy on just one subject is not a good study habit.

Learning also requires choice and focus, and to do it well, you must also know how to choose to 'give up.'

This does not mean that you should give up on related learning altogether, but that you should take a break from your learning pace, even if only for a moment.

--- From "Why results are different even when studying for the same amount of time"

To retrieve memories stored in the mind, humans use something called a 'cue'.

Context helps us learn because it contains many of these clues.

For example, to remember what was learned in class, we may use external cues, such as the desks or teachers around us at the time, or internal contexts, such as drunkenness or sobriety, or good or bad moods.

Learning by using a combination of cues rather than relying solely on specific contextual clues allows you to recall the information you want to remember regardless of the context.

The important thing is to use variable cues well, which are easy tools for 'recalling'.

--- From "What should I think?"

This fact suggests that metacognitive illusions can be corrected in a very simple way.

When studying, you should keep in mind not how well you will remember, but how well you will forget.

We know very well that we forget more than we learn.

But many experimental results tell a different story.

Many students believe they will 'remember' what they learn.

In fact, children are more likely to be asked, "Do I understand this well now?" than to ask, "Will I forget this?" or "At what point will I stop remembering the lesson?" after class.

--- From "Ask not 'How much will you remember', but 'How much will you forget'"

For example, if a child first sees a small, white animal and learns to call it a "puppy," he or she will also respond by calling a small, white cat a "puppy."

As this process is repeated, the categorization process also becomes faster.

Categorization plays a significant role in concept formation, and these categorization strategies become stereotypes through the brain's automatic processing (the unconscious judgment of information about an object).

--- From "The Swamp of Stereotypes That Threaten Children's Confidence"

Many children who fall into the metacognitive illusion suffer from the pressure of having to 'study for a long time'.

Due to the illusion of control, I am spending 3 hours studying when I should have finished in 30 minutes.

If you focus only on English and not on math because your English skills are lacking, you will end up failing both subjects.

Focusing all your energy on just one subject is not a good study habit.

Learning also requires choice and focus, and to do it well, you must also know how to choose to 'give up.'

This does not mean that you should give up on related learning altogether, but that you should take a break from your learning pace, even if only for a moment.

--- From "Why results are different even when studying for the same amount of time"

To retrieve memories stored in the mind, humans use something called a 'cue'.

Context helps us learn because it contains many of these clues.

For example, to remember what was learned in class, we may use external cues, such as the desks or teachers around us at the time, or internal contexts, such as drunkenness or sobriety, or good or bad moods.

Learning by using a combination of cues rather than relying solely on specific contextual clues allows you to recall the information you want to remember regardless of the context.

The important thing is to use variable cues well, which are easy tools for 'recalling'.

--- From "What should I think?"

This fact suggests that metacognitive illusions can be corrected in a very simple way.

When studying, you should keep in mind not how well you will remember, but how well you will forget.

We know very well that we forget more than we learn.

But many experimental results tell a different story.

Many students believe they will 'remember' what they learn.

In fact, children are more likely to be asked, "Do I understand this well now?" than to ask, "Will I forget this?" or "At what point will I stop remembering the lesson?" after class.

--- From "Ask not 'How much will you remember', but 'How much will you forget'"

--- From the text

Publisher's Review

Good achievements beat good brains

Metacognitive techniques for raising thinking children

Do you remember the fable "The Tortoise and the Hare"? It's Aesop's fable about a race between a tortoise and a hare.

We already know that in the race between the tortoise and the hare, the tortoise won.

But strangely enough, many parents want their children to be rabbits.

Whether it's studying or arts and physical education, it means 'I just want the child to learn quickly.'

Reflecting this, in Korea, metacognition is known as the 'study method of the top 1%' or 'how to study well.'

Many parents view metacognition through a means-end framework, thinking that fostering metacognition will help their children "learn faster" or "get 100 on tests."

However, the real purpose of metacognition is to help us realize that the process of developing metacognition is the process of learning.

If parents ignore the various meanings and fun that the learning process provides and focus only on 'increasing the child's learning speed,' the child's metacognition cannot develop.

The reason why parents of elementary school students fall into the delusion that 'children who learn quickly are smart' is because of the fast learning speed of elementary school students.

When it comes to learning at a fast pace, children exhibit several characteristics. First, the younger the child, the more fun they find racing with their friends. Second, because the learning level is not difficult, they complete the learning at a faster pace than expected.

Finally, the third is that children who reach their learning goals easily and quickly become intoxicated by their own success and think of themselves as smart.

However, many children who are accustomed to speed battles and who did quite well in elementary school see their grades decline after advancing to higher level schools.

As the problems become more difficult, it is natural that the learning and achievement speeds slow down, but parents and children who are accustomed to speed battles do not understand this situation.

This is especially true for parents who are not directly involved in the study.

So, when a child is slowing down, we ask questions like, “You were always good at it, why are you acting like this these days?” or “Are you already going through puberty?”

My child is studying hard, what's the problem?

The Core of Metacognitive Strategies: Monitoring and Control

For successful learning, 'monitoring' and 'control', which are the core of metacognitive strategies, must be properly implemented.

Monitoring is the process of evaluating the quality and quantity of one's own knowledge, and control is the process of setting a learning direction based on this monitoring.

If either one of them is not functioning properly, learning is likely to fail.

For example, there are cases where children finish studying early because they think they know the material well, but there are also many cases where the opposite is true.

It is an action that arises from the illusion that one knows something one does not know.

To develop monitoring skills, you need to know what you 'find difficult' and at the same time acknowledge that you 'might not know'.

You can't properly develop your monitoring and control skills if you don't even recognize that you might not know something.

There is a proverb that says, 'A frog can't think of its past as a tadpole.'

Most parents are like frogs.

Parents not only easily forget the process of learning through countless trials and errors, but they also fall into the illusion that they acquired knowledge quickly.

This is also why parents try to quickly pass on the knowledge and information they know to their children without giving them time to learn on their own.

This phenomenon, called 'hindsight bias (the tendency to think as if you knew the outcome of an event from the beginning after learning the outcome)', can be summarized as 'I knew it would turn out this way from the beginning.'

This is another example of faulty metacognition.

Parents with this bias mistakenly believe that they knew everything from the beginning, or that they should know everything.

They believe that their child should be able to do everything as well as they do.

That's why I think, 'I already have the answer in my head, but why is my child so slow?'

It is an 'error of bias' that thinks about the process and results based on the knowledge already acquired without looking back at the state of oneself before acquiring knowledge.

Thinking parents create thinking children.

Parents' Thought Habits for Raising Children with Strong Inner Strength

The problem is that these errors and misconceptions make already anxious parents even more anxious.

And what about the academy's advertising slogans?

It is a blatant phrase that stimulates the psychology of anxious parents, making them think, 'Is my child the only one falling behind?'

But take a closer look at the advertisements for moisturizing academies.

They promote their academies with words like 'fast', 'easy', 'no-failure', 'only', and 'absolute', all of which describe machines.

Children are not machines.

It is natural for children to learn and grow through repeated failures and mistakes that are appropriate for their age.

The metacognitive learning method presented by Professor Lisa Sohn, a professor of psychology at Barnard College, Columbia University and a leading expert in metacognitive psychology, provides much food for thought for parents who are only focused on speed and grades.

Based on numerous research results, it scientifically explains why children get different results even when studying for the same amount of time, what to look for when there is no change in a child's grades despite studying hard, and how to raise a child with the power of thought = inner strength.

Ultimately, this book argues that thinking parents can create thinking children, and that parents' metacognition is just as important as their children's metacognition. It will be the best guide for developing the metacognition of both parents and children.

Metacognitive techniques for raising thinking children

Do you remember the fable "The Tortoise and the Hare"? It's Aesop's fable about a race between a tortoise and a hare.

We already know that in the race between the tortoise and the hare, the tortoise won.

But strangely enough, many parents want their children to be rabbits.

Whether it's studying or arts and physical education, it means 'I just want the child to learn quickly.'

Reflecting this, in Korea, metacognition is known as the 'study method of the top 1%' or 'how to study well.'

Many parents view metacognition through a means-end framework, thinking that fostering metacognition will help their children "learn faster" or "get 100 on tests."

However, the real purpose of metacognition is to help us realize that the process of developing metacognition is the process of learning.

If parents ignore the various meanings and fun that the learning process provides and focus only on 'increasing the child's learning speed,' the child's metacognition cannot develop.

The reason why parents of elementary school students fall into the delusion that 'children who learn quickly are smart' is because of the fast learning speed of elementary school students.

When it comes to learning at a fast pace, children exhibit several characteristics. First, the younger the child, the more fun they find racing with their friends. Second, because the learning level is not difficult, they complete the learning at a faster pace than expected.

Finally, the third is that children who reach their learning goals easily and quickly become intoxicated by their own success and think of themselves as smart.

However, many children who are accustomed to speed battles and who did quite well in elementary school see their grades decline after advancing to higher level schools.

As the problems become more difficult, it is natural that the learning and achievement speeds slow down, but parents and children who are accustomed to speed battles do not understand this situation.

This is especially true for parents who are not directly involved in the study.

So, when a child is slowing down, we ask questions like, “You were always good at it, why are you acting like this these days?” or “Are you already going through puberty?”

My child is studying hard, what's the problem?

The Core of Metacognitive Strategies: Monitoring and Control

For successful learning, 'monitoring' and 'control', which are the core of metacognitive strategies, must be properly implemented.

Monitoring is the process of evaluating the quality and quantity of one's own knowledge, and control is the process of setting a learning direction based on this monitoring.

If either one of them is not functioning properly, learning is likely to fail.

For example, there are cases where children finish studying early because they think they know the material well, but there are also many cases where the opposite is true.

It is an action that arises from the illusion that one knows something one does not know.

To develop monitoring skills, you need to know what you 'find difficult' and at the same time acknowledge that you 'might not know'.

You can't properly develop your monitoring and control skills if you don't even recognize that you might not know something.

There is a proverb that says, 'A frog can't think of its past as a tadpole.'

Most parents are like frogs.

Parents not only easily forget the process of learning through countless trials and errors, but they also fall into the illusion that they acquired knowledge quickly.

This is also why parents try to quickly pass on the knowledge and information they know to their children without giving them time to learn on their own.

This phenomenon, called 'hindsight bias (the tendency to think as if you knew the outcome of an event from the beginning after learning the outcome)', can be summarized as 'I knew it would turn out this way from the beginning.'

This is another example of faulty metacognition.

Parents with this bias mistakenly believe that they knew everything from the beginning, or that they should know everything.

They believe that their child should be able to do everything as well as they do.

That's why I think, 'I already have the answer in my head, but why is my child so slow?'

It is an 'error of bias' that thinks about the process and results based on the knowledge already acquired without looking back at the state of oneself before acquiring knowledge.

Thinking parents create thinking children.

Parents' Thought Habits for Raising Children with Strong Inner Strength

The problem is that these errors and misconceptions make already anxious parents even more anxious.

And what about the academy's advertising slogans?

It is a blatant phrase that stimulates the psychology of anxious parents, making them think, 'Is my child the only one falling behind?'

But take a closer look at the advertisements for moisturizing academies.

They promote their academies with words like 'fast', 'easy', 'no-failure', 'only', and 'absolute', all of which describe machines.

Children are not machines.

It is natural for children to learn and grow through repeated failures and mistakes that are appropriate for their age.

The metacognitive learning method presented by Professor Lisa Sohn, a professor of psychology at Barnard College, Columbia University and a leading expert in metacognitive psychology, provides much food for thought for parents who are only focused on speed and grades.

Based on numerous research results, it scientifically explains why children get different results even when studying for the same amount of time, what to look for when there is no change in a child's grades despite studying hard, and how to raise a child with the power of thought = inner strength.

Ultimately, this book argues that thinking parents can create thinking children, and that parents' metacognition is just as important as their children's metacognition. It will be the best guide for developing the metacognition of both parents and children.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of publication: June 26, 2019

- Page count, weight, size: 260 pages | 448g | 148*210*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788950981891

- ISBN10: 8950981890

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)