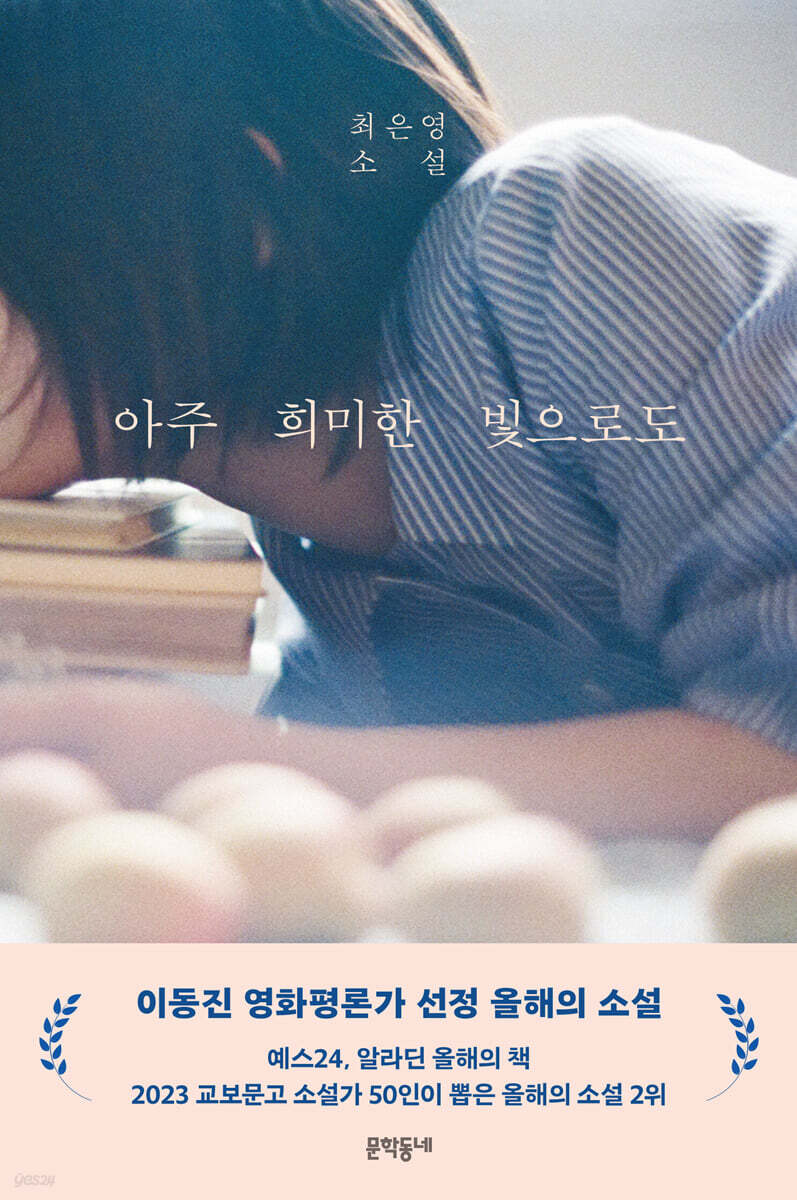

Even in the faintest light

|

Description

Book Introduction

To be more truthful, more fierce, more courageous Five years after "A Person Harmless to Me" The quietly swirling world of Choi Eun-young Recommended by novelist Kwon Yeo-seon and book reviewer Jeong Hee-jin Includes the 2020 Young Writer's Award winning work, "Even in a Very Dim Light" Choi Eun-young's third collection of short stories, "Even with a Very Dim Light," has been published, providing the rare experience of having a "novelist of our generation who has grown together with us," and establishing herself as a special name among fellow writers, critics, and readers alike. Choi Eun-young, who celebrates her 10th debut anniversary this year, has transparently illuminated the intimate and subtle emotions of characters who repeatedly meet and part ways, examining how our private relationships gain a social context (『Shoko's Smile』, 2016). She has also examined how facing memories through a character who persistently recalls the past can become a process of regeneration and recovery (『A Harmless Person to Me』, 2018). By following the life trajectories of characters across four generations, she has depicted how a vertical chronology written from the past to the present positions characters in horizontal relationships and progresses into a horizontal chronology (『Bright Night』, 2021). This collection of short stories, which continues the critical awareness contained in his previous works with a deeper and sharper perspective, shows how the author's original intentions when he first began his career continue to his current perspective, movingly proving that "deepening and broadening are not mutually exclusive in literature" (Hankook Ilbo Literary Award judges' comments). The seven short stories in "Even in a Very Dim Light" stand out for their immersive and appealing power, beginning with a gentle narrative but then suddenly increasing in volume, drawing us into the midst of a fiery passion. “What would you have done? Choi Eun-young's novels, which ask, "What would you have done if you were me?" (Reply, p. 170), actively pull us into the novels from outside the novels, sometimes into the classroom where a character who has just entered college after working feels both overflowing joy and unexpected difficulties ("Even in a Very Dim Light"), sometimes into the car where she carpools with an intern of the same age and has a completely different conversation than before ("One Year"), and sometimes into the lonely seat next to a character who has been pushing herself to prove her existence ("To Aunt"), taking us through the times she spent with them. And through our time with them, he shows us that “our hearts can become attached to the hearts of people who have no relationship with us” (Share, p. 66). That is the power that operates powerfully in Choi Eun-young's new collection of short stories, and it is the power we most desperately need right now: the imagination of others. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Even in the faintest light / 007

Quotient / 047

One year / 085

Reply / 125

Sowing / 181

To my aunt / 213

Disappearing, Not Disappearing / 267

Commentary│Yang Kyung-eon (literary critic)

I want to go further / 321

Author's Note / 347

Quotient / 047

One year / 085

Reply / 125

Sowing / 181

To my aunt / 213

Disappearing, Not Disappearing / 267

Commentary│Yang Kyung-eon (literary critic)

I want to go further / 321

Author's Note / 347

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

To live each day without hating or pitying my shortcomings too much.

It's about continuing to watch over me, knowing that when I'm sad I'm sad, knowing that when I'm angry I'm angry, and knowing that when I love I love.

I think I'm doing something like that right now.

---From the author's note

I still remember the face of the person who said those words.

My heart also trembled when he called cruelty cruelty and resistance resistance out loud.

On the one hand, seeing someone speak so raw about how I felt and what I thought made me feel less alone, but on the other hand, it allowed me to simultaneously face my own cowardice, the inability and unwillingness to do so before.

---From "Even in a Very Dim Light"

Maybe at that time I vaguely wanted to follow her.

Perhaps I wished that someone like me would walk ahead of me, holding a lantern, and let me know that my feet were not in the air.

I don't know where it's going, but I wanted to follow that light, that light that tells me that I can at least keep going without disappearing.

And I wanted to see that light in her, not in anyone else.

---From "Even in a Very Dim Light"

It wasn't all a lie to say that it was the same.

Saying that you are still the same was more like telling each other that, amidst all the changes, the old you still existed, and that I could see that fact.

---From "Share"

You wanted to write something like that.

A piece of writing that once read, you can never go back to the way you were before, a solid and strong piece that no one can refute with logic, a piece that breaks down the wall of the first sentence and moves forward, a piece that prevents the sentences you have already written from becoming a wall for future sentences, a piece that can always transform your feelings and thoughts locked deep inside into words and connect with someone.

---From "Share"

If writing were easy, if it were something you had a natural talent for and could do well without much effort, you might have easily lost interest.

You were captivated by the fact that writing is difficult, painful, tiring, embarrassing, and sometimes even humiliating, yet it also helps you overcome all of that.

The happiness of being able to overcome those limitations, even if only a little, by writing again while recognizing your own limitations through writing, you couldn't go back to the person you were before you realized it.

---From "Share"

I didn't want to be that kind of person.

There are people who live their lives free from the feeling of guilt, thinking that they have done their part to some extent just by reading and writing.

People who feel justified just by criticizing injustice and live forever believing that they are right.

When I was working in the editorial department, I think I was that kind of person to some extent.

That's what I did.

Other people might be different.

Heeyoung said that and looked at you gently.

Sister Jeongyoon said that.

I can't write about this issue.

Maybe that's true.

Sometimes, when my sisters' hearts feel so close to me that I feel like I know what they're thinking, I think about what Jeongyoon said.

Even if I die and wake up, I won't know.

Let's not get confused.

On your way back home after spending the night at that house, you thought of Hee-young's young face.

That was the face of a person in love.

It was the face of a lonely lover.

---From "Share"

Whenever I talk to Dahee, I feel like I'm swimming in warm sea water.

Everything was natural, like water gently wrapping around the body.

After meeting Dahee, she realized that the conversations she had been having up until now were in fact just monologues directed at each other.

Because the conversations she had as an adult were all about filling time, or at least maintaining social relationships, or defending herself.

Only then did she realize that even though she had wanted to be completely alone in her quiet room where no one could hear a sound, and even though she didn't want to hear anyone's voice, she had also wanted to talk to someone.

---From "One Year"

She resigned herself to the situation and hoped it would all pass.

It was painful, but she survived, and she knew what it meant to survive.

Come alive.

If you do that, it will disappear.

The pain, the time to endure it, disappears.

---From "One Year"

She tried not to feel resentful towards Dahee.

Because there was something violent about the feeling of regret.

The feeling that you have to react according to my will.

Regret is less intense than resentment and less direct than hatred, but it is very close to those emotions.

She didn't want to feel that way about Dahee.

---From "One Year"

When you were sleeping and groaning, I wondered about the world that was busily building inside you, and I thought that whatever world it was, it should be protected with care.

What power do you have to grow every day?

How can you, so small, hold up your neck and turn over?

How do small, translucent baby teeth emerge from your gums?

When you held my finger tightly in those soft hands, I knew I was in love with you.

---From "Reply"

But I don't think that was the whole reason we weren't honest back then.

To leave something as if it were not.

Pretending not to know.

That was our old habit of dealing with situations that were beyond our power to handle.

It was also a way of acknowledging that we couldn't be each other's decisive strength.

That's how you deceive yourself.

Everything is fine, it's not a big deal, stirring things up will only make the problem worse.

---From "Reply"

When I couldn't stand it anymore, when I couldn't control myself, I wrote down my feelings in a notebook and then immediately tore it up and threw it away.

I used to think that writing was just writing.

But I think that ultimately, choosing to write something is about conveying the feelings you have.

And that feeling is actually conveyed.

Whether the other person reads the text or not.

---From "Reply"

But it was all just a useless imagination.

She wished she could convey her gratitude and apologies even after death or rebirth, but she couldn't believe that was possible.

Only the simple truth remained in her mind.

The truth was that he was no longer in this world, and there was no way for him to repay the love he had given her.

The truth was that nothing could be undone, and that her feelings for him would remain filled with indelible regret and guilt.

---From "Sowing"

Because my mom and dad were always busy, I spent most of my childhood with my aunt.

I learned the language from my aunt.

Before I started using words like fun, scary, happy, pretty, and bad, my aunt's worldview and interpretations must have been the basis for forming those concepts.

I conceptualized within myself the characteristics of the things my aunt said were pretty, and I did the same for the characteristics of the things my aunt said were bad.

So when I said that I was scared, that I hated, and that I was disgusted, those words contained the worldview and interpretation that had passed through my aunt's life.

---From "To Aunt"

I devoted myself to preparing for the entrance exams out of a longing for stability and independence.

As I pushed myself to the point of pain, surprisingly, the thoughts that were hurting me gradually became less and less frequent.

It was a sadistic way of putting off the real issues by turning a deaf ear, but at the time I believed I was doing pretty well.

(…) I demanded better results from myself than the best I could achieve at my level.

Although my body was tired, I felt good that I could control my body and actions with my mental strength.

The elation of becoming a better being was addictive.

It's about continuing to watch over me, knowing that when I'm sad I'm sad, knowing that when I'm angry I'm angry, and knowing that when I love I love.

I think I'm doing something like that right now.

---From the author's note

I still remember the face of the person who said those words.

My heart also trembled when he called cruelty cruelty and resistance resistance out loud.

On the one hand, seeing someone speak so raw about how I felt and what I thought made me feel less alone, but on the other hand, it allowed me to simultaneously face my own cowardice, the inability and unwillingness to do so before.

---From "Even in a Very Dim Light"

Maybe at that time I vaguely wanted to follow her.

Perhaps I wished that someone like me would walk ahead of me, holding a lantern, and let me know that my feet were not in the air.

I don't know where it's going, but I wanted to follow that light, that light that tells me that I can at least keep going without disappearing.

And I wanted to see that light in her, not in anyone else.

---From "Even in a Very Dim Light"

It wasn't all a lie to say that it was the same.

Saying that you are still the same was more like telling each other that, amidst all the changes, the old you still existed, and that I could see that fact.

---From "Share"

You wanted to write something like that.

A piece of writing that once read, you can never go back to the way you were before, a solid and strong piece that no one can refute with logic, a piece that breaks down the wall of the first sentence and moves forward, a piece that prevents the sentences you have already written from becoming a wall for future sentences, a piece that can always transform your feelings and thoughts locked deep inside into words and connect with someone.

---From "Share"

If writing were easy, if it were something you had a natural talent for and could do well without much effort, you might have easily lost interest.

You were captivated by the fact that writing is difficult, painful, tiring, embarrassing, and sometimes even humiliating, yet it also helps you overcome all of that.

The happiness of being able to overcome those limitations, even if only a little, by writing again while recognizing your own limitations through writing, you couldn't go back to the person you were before you realized it.

---From "Share"

I didn't want to be that kind of person.

There are people who live their lives free from the feeling of guilt, thinking that they have done their part to some extent just by reading and writing.

People who feel justified just by criticizing injustice and live forever believing that they are right.

When I was working in the editorial department, I think I was that kind of person to some extent.

That's what I did.

Other people might be different.

Heeyoung said that and looked at you gently.

Sister Jeongyoon said that.

I can't write about this issue.

Maybe that's true.

Sometimes, when my sisters' hearts feel so close to me that I feel like I know what they're thinking, I think about what Jeongyoon said.

Even if I die and wake up, I won't know.

Let's not get confused.

On your way back home after spending the night at that house, you thought of Hee-young's young face.

That was the face of a person in love.

It was the face of a lonely lover.

---From "Share"

Whenever I talk to Dahee, I feel like I'm swimming in warm sea water.

Everything was natural, like water gently wrapping around the body.

After meeting Dahee, she realized that the conversations she had been having up until now were in fact just monologues directed at each other.

Because the conversations she had as an adult were all about filling time, or at least maintaining social relationships, or defending herself.

Only then did she realize that even though she had wanted to be completely alone in her quiet room where no one could hear a sound, and even though she didn't want to hear anyone's voice, she had also wanted to talk to someone.

---From "One Year"

She resigned herself to the situation and hoped it would all pass.

It was painful, but she survived, and she knew what it meant to survive.

Come alive.

If you do that, it will disappear.

The pain, the time to endure it, disappears.

---From "One Year"

She tried not to feel resentful towards Dahee.

Because there was something violent about the feeling of regret.

The feeling that you have to react according to my will.

Regret is less intense than resentment and less direct than hatred, but it is very close to those emotions.

She didn't want to feel that way about Dahee.

---From "One Year"

When you were sleeping and groaning, I wondered about the world that was busily building inside you, and I thought that whatever world it was, it should be protected with care.

What power do you have to grow every day?

How can you, so small, hold up your neck and turn over?

How do small, translucent baby teeth emerge from your gums?

When you held my finger tightly in those soft hands, I knew I was in love with you.

---From "Reply"

But I don't think that was the whole reason we weren't honest back then.

To leave something as if it were not.

Pretending not to know.

That was our old habit of dealing with situations that were beyond our power to handle.

It was also a way of acknowledging that we couldn't be each other's decisive strength.

That's how you deceive yourself.

Everything is fine, it's not a big deal, stirring things up will only make the problem worse.

---From "Reply"

When I couldn't stand it anymore, when I couldn't control myself, I wrote down my feelings in a notebook and then immediately tore it up and threw it away.

I used to think that writing was just writing.

But I think that ultimately, choosing to write something is about conveying the feelings you have.

And that feeling is actually conveyed.

Whether the other person reads the text or not.

---From "Reply"

But it was all just a useless imagination.

She wished she could convey her gratitude and apologies even after death or rebirth, but she couldn't believe that was possible.

Only the simple truth remained in her mind.

The truth was that he was no longer in this world, and there was no way for him to repay the love he had given her.

The truth was that nothing could be undone, and that her feelings for him would remain filled with indelible regret and guilt.

---From "Sowing"

Because my mom and dad were always busy, I spent most of my childhood with my aunt.

I learned the language from my aunt.

Before I started using words like fun, scary, happy, pretty, and bad, my aunt's worldview and interpretations must have been the basis for forming those concepts.

I conceptualized within myself the characteristics of the things my aunt said were pretty, and I did the same for the characteristics of the things my aunt said were bad.

So when I said that I was scared, that I hated, and that I was disgusted, those words contained the worldview and interpretation that had passed through my aunt's life.

---From "To Aunt"

I devoted myself to preparing for the entrance exams out of a longing for stability and independence.

As I pushed myself to the point of pain, surprisingly, the thoughts that were hurting me gradually became less and less frequent.

It was a sadistic way of putting off the real issues by turning a deaf ear, but at the time I believed I was doing pretty well.

(…) I demanded better results from myself than the best I could achieve at my level.

Although my body was tired, I felt good that I could control my body and actions with my mental strength.

The elation of becoming a better being was addictive.

---From "To Aunt"

Publisher's Review

“There is a part of me that doesn’t know what to do because I want to hurt my sister.

“There was another me fighting, afraid of losing my sister.”

When deep affection and transparent hatred are intricately intertwined

When I belatedly realized the love I received at one time

Seven long letters written with all my heart, contemplating my own share.

Choi Eun-young's novels, which display a remarkable sense of depicting human relationships, are particularly adept at capturing the moments when relationships begin and fall apart, or more precisely, at examining with intense precision what causes those relationships to become distorted.

One of the characteristics of this collection of short stories is that it examines the nature of such relationships in relation to social issues.

As literary critic Yang Kyung-eon accurately points out, “Choi Eun-young’s work has always pointed out that the subtle waves are caused by various social conditions and historical and structural problems,” and she is “still brave in dealing with the problems of reality” (“I Want to Go Further,” commentary on “Even in a Very Dim Light,” p. 332).

Therefore, examining the relationships between characters in a novel cannot be separated from understanding the kind of ground they stand on.

“It is a perfect stitch without a single seam.

“One Year,” which was nominated for the final round of the Lee Hyo-seok Literary Award with the comment “A unique answer to the question of what human relationships are” (critic Jeong Yeo-ul), follows the year that the narrator, Ji-su, spends with Da-hee, a contract intern of the same age when he was a third-year employee.

At the time, Jisoo was in charge of going to the construction site every day to check the situation ahead of the wind power plant opening ceremony, and Dahee had started working as Jisoo's assistant because she was fluent in Chinese.

Despite the difference between a full-time employee and a contract intern, the two carpool together and have a genuine conversation they have never had before while commuting to and from the construction site.

Only through that conversation was there “a heart that revealed itself” (p. 123), but the two people’s different situations created an unexpected rift in their relationship, and they broke up without being able to be honest with each other.

But the novel goes a step further and sets up a situation where the two meet by chance eight years later.

The important thing is that this brief encounter does not serve as a refreshing opportunity for the two to start a new relationship, but rather as a time to honestly reflect on what that one year has meant to each other.

“Even in a Very Dim Light” focuses on depicting such a complex process of disharmony and reconciliation.

Hee-won, a twenty-seven-year-old who worked at a bank and later transferred to the English department at university, is fascinated by a young lecturer named “Her,” who “wears neutral clothes and speaks her thoughts clearly in English with a strong Korean accent” (p. 10).

Through her intellectually stimulating classes, Heewon reflects deeply on whether her writing was not "safe writing" that was concerned about the opinions of others, and approaches writing with a little more seriousness and courage.

However, when she tells him that she wants to go to graduate school, “You can study even if you’re not a graduate school student, Hee-won, you know that too” (page 37), Hee-won is hurt and blurts out words that hurt her pride.

It was only after time had passed and he had become a young instructor like her that Hee-won began to understand why she had said that to him.

When Hee-won, recalling her, calmly confesses, “Although I cannot agree with her, I think I can understand her feelings now,” and “I, too, just wanted to go further. / Perhaps, at that time, I vaguely wanted to follow her” (p. 43), we see a faint but clear light connecting Hee-won and her.

Meanwhile, while "One Year" overlaps the issue of irregular employment on top of changes in relationships, "Even in a Very Dim Light" highlights the space called "Yongsan."

The novel seriously explores the meaning of writing by recalling Yongsan, a space that binds Hee-won and her through shared memories and a place where a disaster occurred due to excessive government suppression, as the basis for writing.

"Share" is also a work that encapsulates the core keywords of this collection of short stories—relationships, society, and writing—and powerfully portrays the achievements, rewards, and limitations experienced through writing by three characters who became close while working together on the school newspaper's editorial staff.

In the fall of 1996, twenty-year-old Hae-jin accidentally picked up a pile of school newspapers in front of the library and was captivated by Jeong-yoon's writing. As if by fate, he joined the school newspaper's editorial department.

Haejin is overwhelmed by the sharp and elegant writing of her peer Heeyoung, but as she gradually begins to write her own, she is captivated by the fact that “writing is difficult, painful, tiring, and embarrassing, and sometimes makes you feel nothing but self-deprecation, but it is also what helps you overcome all that” (p. 75).

However, the situation in the 1990s, which was not much different from today, with its sharp conflicts and debates surrounding women's issues, gradually created a rift between Hae-jin, Hee-young, and Jeong-yoon.

The problematic awareness of "Share", which acknowledges that solidarity and reconciliation are not easily achieved simply because we are all women, and examines the complexity of women's issues, continues in "Reply."

This novel, the most intense of the collected works, is written in the form of a letter sent by 'I' to my sister's daughter whom I can no longer meet.

Why am I writing a letter to my niece and not my sister?

Why can't I meet my sister and niece anymore?

As we read the novel with such curiosity, what we encounter is a violence so strong that it seems impossible to overcome with individual will alone.

'I' begins the letter by telling 'you', my nephew, about my childhood.

'I' grew up neglected by my father after my mother left home, but my older sister, who is 3 years older and has a strong sense of responsibility, has been my parent since I was little and has been my greatest strength.

When did that older sister start to change?

One day, a black sedan stops in front of my house, and unexpectedly, my sister gets out of it.

My sister is embarrassed and makes excuses, saying that she was just given a lift by a teacher she met by chance, but I realize that she is lying.

And my sister says that when she turns twenty-one, she will marry that teacher who is fifteen years older than her.

She said she was pregnant and that the man would take responsibility for her.

But in reality, he ignores his sister so naturally and openly, as if he has nothing to be ashamed of, both at the meeting and after marriage.

'I' am unbearably angry at his attitude, but I feel helpless because I don't know how I can help my sister.

And that anger explodes due to a certain incident.

'I' begins to fight against him with all my might because "I want to protect my beloved sister, and I want to show her that she is a precious person who should not be treated so carelessly" (p. 177).

“What will be the result of the choice made at that time?” (p. 170).

“Even if you don’t want it to, the traces won’t disappear.”

Looking honestly at the traces carved into myself

Moving forward toward others and society

The three novels, “Sowing,” “To Aunt,” and “Disappearing, Not Disappearing,” placed side by side in the latter half, show a family different from what is commonly considered a “normal family.”

"Sowing" is the story of a younger brother who belatedly realizes the love of his older brother who took care of him in place of their mother who passed away early. It delicately captures the feelings shared between siblings against the backdrop of the "garden," a space that metaphorically symbolizes the older brother's attitude toward life and the love he left behind.

As the title suggests, “To My Aunt” is a story written by me as I reminisce about my aunt, with whom I spent most of my childhood.

'I' cannot stand my emotionally stingy and strict aunt, and while trying to deny the mark deeply engraved on me, I also miss my aunt who cared for me in a way no one else did.

Because 'I' am not writing this to judge my aunt.

Because that kind of judgment is too easy.

When we say, “I don’t want to talk about my aunt in that easy way” (p. 217), we realize that accepting her as she is may also mean accepting aspects of ourselves that we find so unbearable.

If "Sowing" deals with siblings and "To Aunt" deals with an aunt and her nephew, "Disappearing, Not Disappearing" takes a long-term look at the most complex and difficult relationship between mother and daughter.

'Kinam', a woman in her sixties, goes on a short trip to meet her younger daughter 'Woo-kyung' who lives in Hong Kong.

What Ki-nam realizes on his trip is the invisible line between himself and Woo-kyung, but the person who unexpectedly becomes a comfort to Ki-nam is his seven-year-old grandson, Michael.

Michael is busy trying to get the attention of Ki-nam whom he hasn't seen in a long time, and at the same time, he throws unexpected words at Ki-nam with a bright expression.

Ki-nam goes on an outing to downtown Hong Kong with Woo-kyung and Michael, but makes a mistake. Returning home to a depressed atmosphere because of him, Ki-nam looks back on his life and suddenly feels ashamed.

But then Michael comes up to Gi-nam and sits down next to him, and as if he had read Gi-nam's mind, he says this.

“It’s okay to be embarrassed.

“It’s cute to be embarrassed” (p. 318).

Kinam carefully stroked Michael's head.

The thick, curly hair was just like when Woo-kyung was young.

“Michael is so sweet.”

"that's right.

My mom said so.

Michael is so affectionate.

“Like a Korean grandmother.”

"really?"

“But you shouldn’t be too affectionate.”

Michael looked at Gi-nam for a moment and then continued speaking.

“Being too affectionate is a bad deal.”

A warm pain spread through Gi-nam's back and stomach.

Kinam nodded quietly while stroking Michael's hair.

Michael didn't know himself and he didn't know the time he had lived.

But at that moment, why did it feel like the person who knew nothing about me understood me better than I did?

It's okay to be embarrassed.

Kinam couldn't believe it.

Words I never expected.

Ki-nam thought he would never forget those words. (p. 319)

The 'warm pain' that Ki-nam feels at Michael's words is similar to the emotion that spreads within us while reading Choi Eun-young's novel.

When a wound is touched precisely, when someone we barely know seems to understand us deeply, when we have a feeling that we will never forget that moment, we become aware of our intimate connection with the other person.

Our existence cannot stand unrelated to anything within relationships or within society.

Choi Eun-young, who has presented brilliant works so far, constantly examines her writing and clearly engraves this image of us into this collection of short stories.

“There was another me fighting, afraid of losing my sister.”

When deep affection and transparent hatred are intricately intertwined

When I belatedly realized the love I received at one time

Seven long letters written with all my heart, contemplating my own share.

Choi Eun-young's novels, which display a remarkable sense of depicting human relationships, are particularly adept at capturing the moments when relationships begin and fall apart, or more precisely, at examining with intense precision what causes those relationships to become distorted.

One of the characteristics of this collection of short stories is that it examines the nature of such relationships in relation to social issues.

As literary critic Yang Kyung-eon accurately points out, “Choi Eun-young’s work has always pointed out that the subtle waves are caused by various social conditions and historical and structural problems,” and she is “still brave in dealing with the problems of reality” (“I Want to Go Further,” commentary on “Even in a Very Dim Light,” p. 332).

Therefore, examining the relationships between characters in a novel cannot be separated from understanding the kind of ground they stand on.

“It is a perfect stitch without a single seam.

“One Year,” which was nominated for the final round of the Lee Hyo-seok Literary Award with the comment “A unique answer to the question of what human relationships are” (critic Jeong Yeo-ul), follows the year that the narrator, Ji-su, spends with Da-hee, a contract intern of the same age when he was a third-year employee.

At the time, Jisoo was in charge of going to the construction site every day to check the situation ahead of the wind power plant opening ceremony, and Dahee had started working as Jisoo's assistant because she was fluent in Chinese.

Despite the difference between a full-time employee and a contract intern, the two carpool together and have a genuine conversation they have never had before while commuting to and from the construction site.

Only through that conversation was there “a heart that revealed itself” (p. 123), but the two people’s different situations created an unexpected rift in their relationship, and they broke up without being able to be honest with each other.

But the novel goes a step further and sets up a situation where the two meet by chance eight years later.

The important thing is that this brief encounter does not serve as a refreshing opportunity for the two to start a new relationship, but rather as a time to honestly reflect on what that one year has meant to each other.

“Even in a Very Dim Light” focuses on depicting such a complex process of disharmony and reconciliation.

Hee-won, a twenty-seven-year-old who worked at a bank and later transferred to the English department at university, is fascinated by a young lecturer named “Her,” who “wears neutral clothes and speaks her thoughts clearly in English with a strong Korean accent” (p. 10).

Through her intellectually stimulating classes, Heewon reflects deeply on whether her writing was not "safe writing" that was concerned about the opinions of others, and approaches writing with a little more seriousness and courage.

However, when she tells him that she wants to go to graduate school, “You can study even if you’re not a graduate school student, Hee-won, you know that too” (page 37), Hee-won is hurt and blurts out words that hurt her pride.

It was only after time had passed and he had become a young instructor like her that Hee-won began to understand why she had said that to him.

When Hee-won, recalling her, calmly confesses, “Although I cannot agree with her, I think I can understand her feelings now,” and “I, too, just wanted to go further. / Perhaps, at that time, I vaguely wanted to follow her” (p. 43), we see a faint but clear light connecting Hee-won and her.

Meanwhile, while "One Year" overlaps the issue of irregular employment on top of changes in relationships, "Even in a Very Dim Light" highlights the space called "Yongsan."

The novel seriously explores the meaning of writing by recalling Yongsan, a space that binds Hee-won and her through shared memories and a place where a disaster occurred due to excessive government suppression, as the basis for writing.

"Share" is also a work that encapsulates the core keywords of this collection of short stories—relationships, society, and writing—and powerfully portrays the achievements, rewards, and limitations experienced through writing by three characters who became close while working together on the school newspaper's editorial staff.

In the fall of 1996, twenty-year-old Hae-jin accidentally picked up a pile of school newspapers in front of the library and was captivated by Jeong-yoon's writing. As if by fate, he joined the school newspaper's editorial department.

Haejin is overwhelmed by the sharp and elegant writing of her peer Heeyoung, but as she gradually begins to write her own, she is captivated by the fact that “writing is difficult, painful, tiring, and embarrassing, and sometimes makes you feel nothing but self-deprecation, but it is also what helps you overcome all that” (p. 75).

However, the situation in the 1990s, which was not much different from today, with its sharp conflicts and debates surrounding women's issues, gradually created a rift between Hae-jin, Hee-young, and Jeong-yoon.

The problematic awareness of "Share", which acknowledges that solidarity and reconciliation are not easily achieved simply because we are all women, and examines the complexity of women's issues, continues in "Reply."

This novel, the most intense of the collected works, is written in the form of a letter sent by 'I' to my sister's daughter whom I can no longer meet.

Why am I writing a letter to my niece and not my sister?

Why can't I meet my sister and niece anymore?

As we read the novel with such curiosity, what we encounter is a violence so strong that it seems impossible to overcome with individual will alone.

'I' begins the letter by telling 'you', my nephew, about my childhood.

'I' grew up neglected by my father after my mother left home, but my older sister, who is 3 years older and has a strong sense of responsibility, has been my parent since I was little and has been my greatest strength.

When did that older sister start to change?

One day, a black sedan stops in front of my house, and unexpectedly, my sister gets out of it.

My sister is embarrassed and makes excuses, saying that she was just given a lift by a teacher she met by chance, but I realize that she is lying.

And my sister says that when she turns twenty-one, she will marry that teacher who is fifteen years older than her.

She said she was pregnant and that the man would take responsibility for her.

But in reality, he ignores his sister so naturally and openly, as if he has nothing to be ashamed of, both at the meeting and after marriage.

'I' am unbearably angry at his attitude, but I feel helpless because I don't know how I can help my sister.

And that anger explodes due to a certain incident.

'I' begins to fight against him with all my might because "I want to protect my beloved sister, and I want to show her that she is a precious person who should not be treated so carelessly" (p. 177).

“What will be the result of the choice made at that time?” (p. 170).

“Even if you don’t want it to, the traces won’t disappear.”

Looking honestly at the traces carved into myself

Moving forward toward others and society

The three novels, “Sowing,” “To Aunt,” and “Disappearing, Not Disappearing,” placed side by side in the latter half, show a family different from what is commonly considered a “normal family.”

"Sowing" is the story of a younger brother who belatedly realizes the love of his older brother who took care of him in place of their mother who passed away early. It delicately captures the feelings shared between siblings against the backdrop of the "garden," a space that metaphorically symbolizes the older brother's attitude toward life and the love he left behind.

As the title suggests, “To My Aunt” is a story written by me as I reminisce about my aunt, with whom I spent most of my childhood.

'I' cannot stand my emotionally stingy and strict aunt, and while trying to deny the mark deeply engraved on me, I also miss my aunt who cared for me in a way no one else did.

Because 'I' am not writing this to judge my aunt.

Because that kind of judgment is too easy.

When we say, “I don’t want to talk about my aunt in that easy way” (p. 217), we realize that accepting her as she is may also mean accepting aspects of ourselves that we find so unbearable.

If "Sowing" deals with siblings and "To Aunt" deals with an aunt and her nephew, "Disappearing, Not Disappearing" takes a long-term look at the most complex and difficult relationship between mother and daughter.

'Kinam', a woman in her sixties, goes on a short trip to meet her younger daughter 'Woo-kyung' who lives in Hong Kong.

What Ki-nam realizes on his trip is the invisible line between himself and Woo-kyung, but the person who unexpectedly becomes a comfort to Ki-nam is his seven-year-old grandson, Michael.

Michael is busy trying to get the attention of Ki-nam whom he hasn't seen in a long time, and at the same time, he throws unexpected words at Ki-nam with a bright expression.

Ki-nam goes on an outing to downtown Hong Kong with Woo-kyung and Michael, but makes a mistake. Returning home to a depressed atmosphere because of him, Ki-nam looks back on his life and suddenly feels ashamed.

But then Michael comes up to Gi-nam and sits down next to him, and as if he had read Gi-nam's mind, he says this.

“It’s okay to be embarrassed.

“It’s cute to be embarrassed” (p. 318).

Kinam carefully stroked Michael's head.

The thick, curly hair was just like when Woo-kyung was young.

“Michael is so sweet.”

"that's right.

My mom said so.

Michael is so affectionate.

“Like a Korean grandmother.”

"really?"

“But you shouldn’t be too affectionate.”

Michael looked at Gi-nam for a moment and then continued speaking.

“Being too affectionate is a bad deal.”

A warm pain spread through Gi-nam's back and stomach.

Kinam nodded quietly while stroking Michael's hair.

Michael didn't know himself and he didn't know the time he had lived.

But at that moment, why did it feel like the person who knew nothing about me understood me better than I did?

It's okay to be embarrassed.

Kinam couldn't believe it.

Words I never expected.

Ki-nam thought he would never forget those words. (p. 319)

The 'warm pain' that Ki-nam feels at Michael's words is similar to the emotion that spreads within us while reading Choi Eun-young's novel.

When a wound is touched precisely, when someone we barely know seems to understand us deeply, when we have a feeling that we will never forget that moment, we become aware of our intimate connection with the other person.

Our existence cannot stand unrelated to anything within relationships or within society.

Choi Eun-young, who has presented brilliant works so far, constantly examines her writing and clearly engraves this image of us into this collection of short stories.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 7, 2023

- Page count, weight, size: 352 pages | 496g | 133*200*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788954695053

- ISBN10: 8954695051

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)