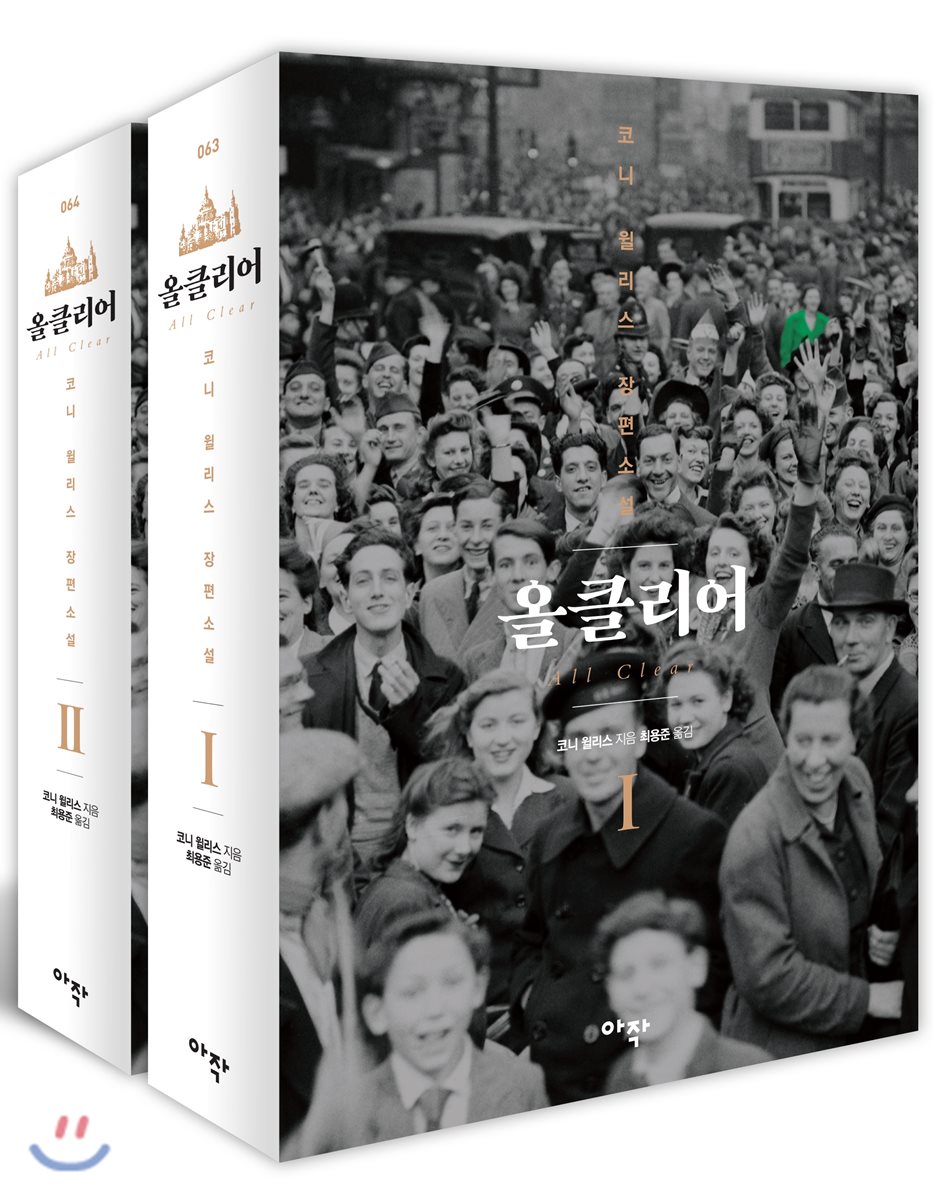

All Clear 1,2 sets

|

Description

Book Introduction

This product is a product made by YES24. (Individual returns are not possible.) [Book] All Clear 1 | Author/Translator | Ajak (Design Comma) [Book] All Clear 2 | Author/Translator | Ajak (Design Comma) Following 『Fire Watch』 『Doomsday Book』 『Dogs and Dogs』 『Blackout』 The Oxford Time Travel Series Finally Concludes The greatest time travel series completed in 30 years Oxford in 2060 is thrown into chaos when dozens of time-traveling historians are sent back in time. Michael Davis is preparing to go to Pearl Harbor. Merope Ward is dealing with refugee children from 1940 and, once this mission is over, is trying to convince Professor Dunworthy to let her attend the war memorial service. Polly Churchill's next assignment is as a clerk in a department store in the heart of London's Oxford Street. But suddenly the lab canceled all missions and changed the schedules of all historians. And things get worse when Michael, Merope, and Polly finally arrive in World War II. There they face air raids, blackouts, and bomb clearance, and there is a growing sense that not only their mission, but the war and history itself are spiraling out of control. The once-reliable mechanism of time travel began to show major flaws. Our heroes began to doubt their own unwavering convictions. “Can historians really not change the past?” |

index

Volume 1

1_1

2_12

3_24

4_44

5_60

6_76

7_82

8_112

9_122

10_130

11_145

12_156

13_170

14_190

15_213

16_230

17_247

18_260

19_284

20_301

21_312

22_328

23_341

24_358

25_369

26_382

27_400

28_419

29_433

30_448

31_457

32_476

33_492

34_518

35_533

1_1

2_12

3_24

4_44

5_60

6_76

7_82

8_112

9_122

10_130

11_145

12_156

13_170

14_190

15_213

16_230

17_247

18_260

19_284

20_301

21_312

22_328

23_341

24_358

25_369

26_382

27_400

28_419

29_433

30_448

31_457

32_476

33_492

34_518

35_533

Volume 2

36_555

37_564

38_585

39_601

40_623

41_641

42_649

43_672

44_692

45_707

46_722

47_735

48_744

49_771

50_786

51_810

52_828

53_844

54_862

55_875

56_895

57_904

58_919

59_935

60_951

61_969

62_987

63_1013

64_1016

65_1037

66_1051

67_1067

68_1090 Volume 2

36_555

37_564

38_585

39_601

40_623

41_641

42_649

43_672

44_692

45_707

46_722

47_735

48_744

49_771

50_786

51_810

52_828

53_844

54_862

55_875

56_895

57_904

58_919

59_935

60_951

61_969

62_987

63_1013

64_1016

65_1037

66_1051

67_1067

68_1090

36_555

37_564

38_585

39_601

40_623

41_641

42_649

43_672

44_692

45_707

46_722

47_735

48_744

49_771

50_786

51_810

52_828

53_844

54_862

55_875

56_895

57_904

58_919

59_935

60_951

61_969

62_987

63_1013

64_1016

65_1037

66_1051

67_1067

68_1090 Volume 2

36_555

37_564

38_585

39_601

40_623

41_641

42_649

43_672

44_692

45_707

46_722

47_735

48_744

49_771

50_786

51_810

52_828

53_844

54_862

55_875

56_895

57_904

58_919

59_935

60_951

61_969

62_987

63_1013

64_1016

65_1037

66_1051

67_1067

68_1090

Publisher's Review

All five works in the series won Hugo Awards!

Winner of the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus Awards!

This is the masterpiece of Connie Willis, who has won 11 Hugo Awards, 7 Nebula Awards, and 12 Locus Awards, establishing herself as a true SF grandmaster and authority. It is also the final full-length novel in the Oxford Time Travel series, which continues the worldview of the short story "The Fire Watch."

Winner of the Hugo Award, Nebula Award, and Locus Award!

The journey of miracles continues.

Connie Willis has proven once again that she is one of America's greatest writers.

- Denver Post

Connie Willis's bizarre and moving leap

Finally, the latest installment in Connie Willis' Oxford Time Travel series, All Clear, has arrived.

This piece appears to be the last in the series.

Because it followed the rules of sequels too well.

In fact, "All Clear," which should be considered the same work as the previous work, "Blackout," is the largest and most complex work in the series.

Connie Willis herself even commented on this work, saying, “I pushed it to the limit.”

If I hadn't thought this was the end, I might not have made the plot so complicated.

Connie Willis, who poured all her energy into this, didn't lose as if it were a lie.

I hope you are doing well with your work.

However, it seems like it will be a long time before this time travel series returns.

Connie Willis wasn't the kind of writer who enjoyed juggling complex and varied storylines like a grand symphony.

Reading "All Clear" makes you feel like the author's own words about pushing himself to the limit are sincere.

Including 『Blackout』, which can be compiled into a single work, this novel reaches 2,000 pages in Korean edition.

The number of characters is much larger.

The main timelines in which time travelers operate will also expand.

The years 1941 and 1944, along with the year 2060, which can be considered the 'present' time in the novel's setting, have a close influence on each other, and additional time periods that play a secondary role appear.

Since the same character often appears in more than one time period, it can be confusing at first.

During 『Blackout』.

However, those of you who are challenging 『All Clear』 will have already overcome that confusion.

But the problem arises again.

The plot of this novel, which unfolds across different time periods, was an unavoidable problem.

It feels like it's going nowhere.

As seen in "Blackout," the time "fall" suddenly becomes too great, so you can't arrive in London in 1941 or 1944 at your desired time.

So some time travelers were stuck in 1941, some in 1944, and some in both 1941 and 1944.

The protagonists of 1941 and 1944 influence each other, but the problem is that even if one of these two time periods discovers something, there is no way to convey it to the other.

So the reader is left to watch characters from one timeline unravel some of the mystery surrounding time travel, and then watch characters from another timeline grapple with nearly identical issues.

So the story of 『All Clear』 flows slowly.

If it were a longer, slower novel, it might feel like a fatal problem to some readers.

So, some fans say that if 『All Clear』 were shortened by about a third, it would be a better novel.

In terms of storytelling efficiency, that might be true.

As I mentioned earlier, this novel, which is inherently slow to develop due to its plot structure, is filled with numerous details that further slow down the pace.

Don't skimp on the dedication of this novel.

All the professions featured here are also active in the novel (does a mystery writer really appear? Agatha Christie 'appears').

"All Clear" spares no effort in showing how these little heroes live.

There are quite a few anecdotes that have almost nothing to do with the main story, so it's hard to call them subplots.

Could this be called a clutter?

If it were really just extraneous elements, why would Connie Willis, who knows how to write short stories effectively, leave them in?

There's no way I didn't know.

Let's picture the plot of "All Clear".

I imagine small short stories and leaflets branching out like branches from the large trunk of a novel, forming one body.

The main trunk is the story of time travelers, and the smaller branches are the stories of Londoners who encourage each other and carry on living amidst German air raids.

For efficiency, it is okay to prune all the branches.

The 'mystery of the space-time continuum', the most important material in 'All Clear', goes beyond what was shown in the previous Oxford time travel series.

Even if we had only deduced the key events surrounding this shift in thinking, it would have been a fascinating work (or even more so, depending on the reader).

It's a nice, smooth log that's been trimmed to look good.

That's the typical novel writing style.

But why didn't Connie Willis do that?

Even while suffering myself.

The reason is that the theme of this novel is to show how small branches form a single tree with a large trunk.

I mean, the little branches of ordinary, generally good people's lives.

This was actually a message that ran through the entire Oxford Time Travel series, and indeed the entire world of Connie Willis's work (see the introduction to Connie Willis's Christmas short story collection).

Especially in the Oxford Time Travel series, the question of why such innocent and good people are subjected to suffering continues.

That is, the question is what salvation is.

Bartholomew, the protagonist of the short story "The Fire Watch" that started this series, is furious that humans must accept the tragic fate given to them.

The question raised here becomes even clearer in the next work, Doomsday Book.

In this work, which borrows its form from the Biblical Passion Play, the time traveler and the characters around him reenact Jesus' actions in their own way (though perhaps unconsciously).

But this method could not help but remain a kind of allegory.

Because the person who reenacted Jesus' actions was not Jesus, and therefore the miracle did not occur.

The Protestant doctrine that humans cannot save humans remains unchanged.

'History' is fixed, fate does not change, and the good are never more blessed.

The theological question of why the Lord causes suffering to the lambs of the Lord and the good little branches, however, takes a major turn in All Clear.

This major turning point, which begins to reveal its true identity about halfway through the novel, is the novel's central plot point and emotional driving force.

If you're a fan of the series, you should read "All Clear" just to get this far.

It is difficult to elaborate on this.

But it would be better to keep the story simple.

Connie Willis made a bold choice.

Because it changed the nature of this 'space-time continuum', the system that supports the world called 'Oxford Time Travel Series', which has no personality or consciousness but has four-dimensional powers.

Given a few scenes in the latter half, it seems clear what direction Connie Willis's new choices are pointing.

Now Connie Willis makes no secret of her desires.

Connie Willis, who previously equated human hope with apathetic goodness, now boldly advances beyond that.

The reason it's bold is because at first glance it seems so naive.

Even in the novel, someone says:

“There is no evidence,” he said.

What's the point of a hypothesis filled with unproven good wishes? Is it any different from the idea of going to heaven after death? If so, isn't the bold shift in worldview that "All Clear" boldly unfolds a futile endeavor?

Yes, it may be a futile attempt.

And that futility shines beautifully in this novel.

Because "All Clear" is a tribute and memorial to all the insignificant, small, and good events and people (I encourage you to read the tribute again after you've finished the novel).

Beyond Doomsday Book, where weak humans struggle alone against fate in a universe devoid of God, Allclear suggests that God may not be absent, but merely watching (or intervening only in ways we don't understand).

Isn't it the same in the end? No.

A French theologian said:

How much love would it take for a being with truly omnipotent power to endure and watch without using that power?

"All Clear" finally reveals this innocent and pure will.

The power to look after all the people in the world, even the smallest branches, and cherish them whether they prosper or perish.

Or the moment you truly believe that such a power exists.

The Oxford Time Travel series has soared to such heights.

ps: Actually, it might be more appropriate to write 'It ended flying so high like this'.

However, if you're a fan of the series, you'll notice that I didn't mention "The Dog".

The mysteries (or clues) presented in this delightful spin-off remain unsolved.

Also, given the development of this series, which has been a tragedy-comedy-tragedy(?) so far, I have a strange feeling that the series will end with something really funny and happy, like a sweet and sour ending.

Yes? Oh, of course, “there is no evidence.”

★★★★★ 2011 Hugo Award Winner

★★★★★ Winner of the 2011 Nebula Award

★★★★★ 2011 Locus Award Winner

★★★★☆ Nominated for the 2011 Campbell Award

Translator's Note

“Is it a comedy or a tragedy?”

Translation is like opening a window to let light in.

Breaking the shell so that the kernel can be eaten,

Pulling back the curtains so that we can see the sacred ground.

Opening the well lid so that water can be drunk.

― From the translator to the reader, 『King James Bible』

HG

Wells's Occupation - Occupations Suffering from Time Travel - Oxford - The Rules of Time Travel

― Shakespeare ― The Importance of Cell Phones ― Ultimately a Comedy

HG, a science journalist, civilization critic, and novelist

Since Wells wrote The Time Machine in 1895, many writers have shown great interest in the subject of time travel.

In fact, time travel has become one of the most widely used themes in the science fiction genre, alongside faster-than-light flight.

Of course, there were novels about time travel before Wells (Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889) is one example), but Wells's The Time Machine was the first to introduce time travel through scientific methods (in the novel) rather than through wish-granting or time-slip methods relying on a transcendent being.

In other words, The Time Machine is a classic time travel novel, a work that combines Wells's sensibility ahead of its time, the possibility of the future (where the novelistic imagination is fully developed) that can be said to be a characteristic of science fiction, and sharp satire that compares the social structure of the time to the future.

The description of the end of the sun in particular is surprising considering that at the time the work was published, astronomical research on stellar evolution was still virtually non-existent.

Whether time travel is possible or not is a matter for discussion among scientists studying quantum mechanics or relativity, but the current trend is that research results are coming out in the direction of time travel being impossible (the most famous debate about the possibility of time travel is the wormhole-time machine debate between Kip Thorne and Stephen Hawking).

If you are curious about the debate between these two and the possibility of time travel, see "Do the Laws of Physics Permit Wormholes for Interstellar Travel and Machines for Time Travel?" by Kip Thorne in Carl Sagan's Universe (1997).

However, since no definitive conclusion has been reached yet, it is still too early to conclude that time travel is absolutely impossible.

Therefore, there is no need to give up on the dream of time travel, and those who are interested in it would do well to pay attention to tenses for writing about time travel.

(The problem of defining tenses according to time travel is also a task for theoretical linguists.

If you are interested in more about time travel and tenses, see The Theory and Practice of Time Travel (1973) by Larry Niven, known for The Ring World (1970).

And if time travel is possible, theologians cannot be free from related discussions either.

For example, if time travel is possible, where in the "present" are the souls of those we have met and converted in the past or future? For a theological perspective on time travel, see Ingela Madfor, "Backward Time Travel and Its Relevance for Theological Study" (2011).

As we have seen, although the idea of time travel has been explored in science and may be explored in other fields in the future, it is currently most actively explored in fiction.

And of all the novels that have dealt with time travel to date, the best are Connie Willis's Time Travel series, set at Oxford University.

The Oxford Time Travel series began with the novella The Fire Watch (1982), followed by the novels Doomsday Book (1992), To Say No to Dogs (1997), and the two-part series Blackout and All Clear (2010). All four works won the Hugo Award, and three won the Nebula Award (To Say No to Dogs was a finalist for the Nebula Award).

Considering that the Hugo Awards are chosen by popular vote among readers, while the Nebula Awards are decided by writers and critics, Connie Willis's series is a work that has received recognition from both readers and critics.

This series, which began with the 1982 novella "The Fire Watch," is set in the mid-21st century, when time travel has become possible, and deals with the events that unfold as the story travels back in time to the past, set in the Department of History at Oxford University in England.

When we look at novels that deal with time travel, we see that authors create and apply their own rules.

For example, Wells assumed the most liberal rule that could be allowed for time travel: that characters could visit the past and future without any restrictions.

Therefore, in "The Time Machine," the time traveler can act as he wishes, and the difficulties the protagonist encounters are merely devices to highlight the protagonist's abilities.

But Connie Willis enforces the strictest of time travel rules.

That is, due to the elasticity of space-time, it was assumed that a time traveler could never reverse causality, and even could not arrive at the desired space-time precisely due to deviation.

It was also assumed that no object could be brought or taken away that could potentially reverse causality (from this perspective, Colin's trip to the Middle Ages in Domesday Book with aspirin and a flashlight could be understood not as a misconception, but as a result of the fact that everyone around him was already dead, so nothing could be changed).

Therefore, the past is not a time of fools who are fooled by the present or future figures, but a time of equal relations, and the time traveler is limited to the role of a thorough observer who knows the outcome but cannot influence it in any way.

The Fire Watch, Doomsday Book, and Of Course the Dogs Were Based on These Basic Rules.

And in recent works like 『Blackout』 and 『All Clear』, this rule becomes more expanded and complex, assuming that deviations are not devices to prevent contradictions from occurring, but rather post-facto measures to resolve contradictions that have arisen.

This series has the important characteristic of recreating historical reality through extensive research, and for this reason, it can be said to be both science fiction and historical novel.

In fact, it took Connie Willis anywhere from five to eight years to complete each work, as she collected historical research.

Another characteristic of Connie Willis that runs through this series is his ability to do both comedy and tragedy.

It is common to find confessions that readers who first read the consistently cheerful "Dogs and All" with its comical yet serious atmosphere about the possibility of the universe being destroyed because of a cat were shocked by the endlessly dark development of "Doomsday Book" set during the Black Death, and there is even a conspiracy theory called "Connie Willis II" that there are separate writers of comedies and tragedies because of her writing style that freely crosses between comedy and tragedy.

His talent reaches its peak in 『Blackout』 and 『All Clear』, which provide the pleasure of reading through the exquisite combination of comedy and tragedy, the dialogue of characters and description of the period reminiscent of the works of Shakespeare, and the detailed plot setting like a mystery novel (as the author admits to being a mystery novel fan).

If there's one complaint readers have about this series as a whole, it's that Oxford in 2050-60 doesn't feel like a futuristic world at all.

For example, Oxford in 2054, as depicted in the novel Domesday Book, is not much different from the present, and in some ways is even behind in science and technology (think of 2054 without mobile phones).

However, if we consider that the purpose of science fiction is never to accurately predict the future through extrapolation, the inaccuracy of the science and technology of the future society depicted in this series cannot be a major flaw.

Rather, to borrow a phrase from Haruki Murakami, you could think of it as an alternative history novel about a world with time machines but no cell phones.

From John Bartholomew of The Fire Watch, who maintained an onlooker's attitude that he could not interfere with history in any way, to Kivrin of Doomsday Book, who tried to save people even though she knew it was impossible, to Verity and Ned of Of Course the Dog, who tried to correct their mistakes, fearing that their mistakes might change the outcome of the war, to Polly, Eileen, and Mike of Blackout and All Clear, who are now actively participating in history themselves, Connie Willis's works have continued to develop and change.

But what remains consistent through all these changes is that, as Polly answered Lord Godfrey's question, "Is it a comedy or a tragedy?" with "It is a comedy."

This is a part that clearly shows the love for humanity that Connie Willis has for humanity, who has published numerous works over the past 40 years since 1978 and has told stories of human courage and hope in all of her works.

Even back in 2000, when I was translating "The Dog Needs No Saying," I never imagined that I would end up doing this entire series over such a long period of time.

After that, I translated 『Doomsday Book』, and then, through connections, I translated 『The Fire Watch』, 『Blackout』, and 『All Clear』.

While the translation may not be free from mistranslations, I hope that this series will allow you to experience the bright light and beautiful scenery, and to eat and drink delicious grains and clear water.

- Choi Yong-jun

Winner of the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus Awards!

This is the masterpiece of Connie Willis, who has won 11 Hugo Awards, 7 Nebula Awards, and 12 Locus Awards, establishing herself as a true SF grandmaster and authority. It is also the final full-length novel in the Oxford Time Travel series, which continues the worldview of the short story "The Fire Watch."

Winner of the Hugo Award, Nebula Award, and Locus Award!

The journey of miracles continues.

Connie Willis has proven once again that she is one of America's greatest writers.

- Denver Post

Connie Willis's bizarre and moving leap

Finally, the latest installment in Connie Willis' Oxford Time Travel series, All Clear, has arrived.

This piece appears to be the last in the series.

Because it followed the rules of sequels too well.

In fact, "All Clear," which should be considered the same work as the previous work, "Blackout," is the largest and most complex work in the series.

Connie Willis herself even commented on this work, saying, “I pushed it to the limit.”

If I hadn't thought this was the end, I might not have made the plot so complicated.

Connie Willis, who poured all her energy into this, didn't lose as if it were a lie.

I hope you are doing well with your work.

However, it seems like it will be a long time before this time travel series returns.

Connie Willis wasn't the kind of writer who enjoyed juggling complex and varied storylines like a grand symphony.

Reading "All Clear" makes you feel like the author's own words about pushing himself to the limit are sincere.

Including 『Blackout』, which can be compiled into a single work, this novel reaches 2,000 pages in Korean edition.

The number of characters is much larger.

The main timelines in which time travelers operate will also expand.

The years 1941 and 1944, along with the year 2060, which can be considered the 'present' time in the novel's setting, have a close influence on each other, and additional time periods that play a secondary role appear.

Since the same character often appears in more than one time period, it can be confusing at first.

During 『Blackout』.

However, those of you who are challenging 『All Clear』 will have already overcome that confusion.

But the problem arises again.

The plot of this novel, which unfolds across different time periods, was an unavoidable problem.

It feels like it's going nowhere.

As seen in "Blackout," the time "fall" suddenly becomes too great, so you can't arrive in London in 1941 or 1944 at your desired time.

So some time travelers were stuck in 1941, some in 1944, and some in both 1941 and 1944.

The protagonists of 1941 and 1944 influence each other, but the problem is that even if one of these two time periods discovers something, there is no way to convey it to the other.

So the reader is left to watch characters from one timeline unravel some of the mystery surrounding time travel, and then watch characters from another timeline grapple with nearly identical issues.

So the story of 『All Clear』 flows slowly.

If it were a longer, slower novel, it might feel like a fatal problem to some readers.

So, some fans say that if 『All Clear』 were shortened by about a third, it would be a better novel.

In terms of storytelling efficiency, that might be true.

As I mentioned earlier, this novel, which is inherently slow to develop due to its plot structure, is filled with numerous details that further slow down the pace.

Don't skimp on the dedication of this novel.

All the professions featured here are also active in the novel (does a mystery writer really appear? Agatha Christie 'appears').

"All Clear" spares no effort in showing how these little heroes live.

There are quite a few anecdotes that have almost nothing to do with the main story, so it's hard to call them subplots.

Could this be called a clutter?

If it were really just extraneous elements, why would Connie Willis, who knows how to write short stories effectively, leave them in?

There's no way I didn't know.

Let's picture the plot of "All Clear".

I imagine small short stories and leaflets branching out like branches from the large trunk of a novel, forming one body.

The main trunk is the story of time travelers, and the smaller branches are the stories of Londoners who encourage each other and carry on living amidst German air raids.

For efficiency, it is okay to prune all the branches.

The 'mystery of the space-time continuum', the most important material in 'All Clear', goes beyond what was shown in the previous Oxford time travel series.

Even if we had only deduced the key events surrounding this shift in thinking, it would have been a fascinating work (or even more so, depending on the reader).

It's a nice, smooth log that's been trimmed to look good.

That's the typical novel writing style.

But why didn't Connie Willis do that?

Even while suffering myself.

The reason is that the theme of this novel is to show how small branches form a single tree with a large trunk.

I mean, the little branches of ordinary, generally good people's lives.

This was actually a message that ran through the entire Oxford Time Travel series, and indeed the entire world of Connie Willis's work (see the introduction to Connie Willis's Christmas short story collection).

Especially in the Oxford Time Travel series, the question of why such innocent and good people are subjected to suffering continues.

That is, the question is what salvation is.

Bartholomew, the protagonist of the short story "The Fire Watch" that started this series, is furious that humans must accept the tragic fate given to them.

The question raised here becomes even clearer in the next work, Doomsday Book.

In this work, which borrows its form from the Biblical Passion Play, the time traveler and the characters around him reenact Jesus' actions in their own way (though perhaps unconsciously).

But this method could not help but remain a kind of allegory.

Because the person who reenacted Jesus' actions was not Jesus, and therefore the miracle did not occur.

The Protestant doctrine that humans cannot save humans remains unchanged.

'History' is fixed, fate does not change, and the good are never more blessed.

The theological question of why the Lord causes suffering to the lambs of the Lord and the good little branches, however, takes a major turn in All Clear.

This major turning point, which begins to reveal its true identity about halfway through the novel, is the novel's central plot point and emotional driving force.

If you're a fan of the series, you should read "All Clear" just to get this far.

It is difficult to elaborate on this.

But it would be better to keep the story simple.

Connie Willis made a bold choice.

Because it changed the nature of this 'space-time continuum', the system that supports the world called 'Oxford Time Travel Series', which has no personality or consciousness but has four-dimensional powers.

Given a few scenes in the latter half, it seems clear what direction Connie Willis's new choices are pointing.

Now Connie Willis makes no secret of her desires.

Connie Willis, who previously equated human hope with apathetic goodness, now boldly advances beyond that.

The reason it's bold is because at first glance it seems so naive.

Even in the novel, someone says:

“There is no evidence,” he said.

What's the point of a hypothesis filled with unproven good wishes? Is it any different from the idea of going to heaven after death? If so, isn't the bold shift in worldview that "All Clear" boldly unfolds a futile endeavor?

Yes, it may be a futile attempt.

And that futility shines beautifully in this novel.

Because "All Clear" is a tribute and memorial to all the insignificant, small, and good events and people (I encourage you to read the tribute again after you've finished the novel).

Beyond Doomsday Book, where weak humans struggle alone against fate in a universe devoid of God, Allclear suggests that God may not be absent, but merely watching (or intervening only in ways we don't understand).

Isn't it the same in the end? No.

A French theologian said:

How much love would it take for a being with truly omnipotent power to endure and watch without using that power?

"All Clear" finally reveals this innocent and pure will.

The power to look after all the people in the world, even the smallest branches, and cherish them whether they prosper or perish.

Or the moment you truly believe that such a power exists.

The Oxford Time Travel series has soared to such heights.

ps: Actually, it might be more appropriate to write 'It ended flying so high like this'.

However, if you're a fan of the series, you'll notice that I didn't mention "The Dog".

The mysteries (or clues) presented in this delightful spin-off remain unsolved.

Also, given the development of this series, which has been a tragedy-comedy-tragedy(?) so far, I have a strange feeling that the series will end with something really funny and happy, like a sweet and sour ending.

Yes? Oh, of course, “there is no evidence.”

★★★★★ 2011 Hugo Award Winner

★★★★★ Winner of the 2011 Nebula Award

★★★★★ 2011 Locus Award Winner

★★★★☆ Nominated for the 2011 Campbell Award

Translator's Note

“Is it a comedy or a tragedy?”

Translation is like opening a window to let light in.

Breaking the shell so that the kernel can be eaten,

Pulling back the curtains so that we can see the sacred ground.

Opening the well lid so that water can be drunk.

― From the translator to the reader, 『King James Bible』

HG

Wells's Occupation - Occupations Suffering from Time Travel - Oxford - The Rules of Time Travel

― Shakespeare ― The Importance of Cell Phones ― Ultimately a Comedy

HG, a science journalist, civilization critic, and novelist

Since Wells wrote The Time Machine in 1895, many writers have shown great interest in the subject of time travel.

In fact, time travel has become one of the most widely used themes in the science fiction genre, alongside faster-than-light flight.

Of course, there were novels about time travel before Wells (Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889) is one example), but Wells's The Time Machine was the first to introduce time travel through scientific methods (in the novel) rather than through wish-granting or time-slip methods relying on a transcendent being.

In other words, The Time Machine is a classic time travel novel, a work that combines Wells's sensibility ahead of its time, the possibility of the future (where the novelistic imagination is fully developed) that can be said to be a characteristic of science fiction, and sharp satire that compares the social structure of the time to the future.

The description of the end of the sun in particular is surprising considering that at the time the work was published, astronomical research on stellar evolution was still virtually non-existent.

Whether time travel is possible or not is a matter for discussion among scientists studying quantum mechanics or relativity, but the current trend is that research results are coming out in the direction of time travel being impossible (the most famous debate about the possibility of time travel is the wormhole-time machine debate between Kip Thorne and Stephen Hawking).

If you are curious about the debate between these two and the possibility of time travel, see "Do the Laws of Physics Permit Wormholes for Interstellar Travel and Machines for Time Travel?" by Kip Thorne in Carl Sagan's Universe (1997).

However, since no definitive conclusion has been reached yet, it is still too early to conclude that time travel is absolutely impossible.

Therefore, there is no need to give up on the dream of time travel, and those who are interested in it would do well to pay attention to tenses for writing about time travel.

(The problem of defining tenses according to time travel is also a task for theoretical linguists.

If you are interested in more about time travel and tenses, see The Theory and Practice of Time Travel (1973) by Larry Niven, known for The Ring World (1970).

And if time travel is possible, theologians cannot be free from related discussions either.

For example, if time travel is possible, where in the "present" are the souls of those we have met and converted in the past or future? For a theological perspective on time travel, see Ingela Madfor, "Backward Time Travel and Its Relevance for Theological Study" (2011).

As we have seen, although the idea of time travel has been explored in science and may be explored in other fields in the future, it is currently most actively explored in fiction.

And of all the novels that have dealt with time travel to date, the best are Connie Willis's Time Travel series, set at Oxford University.

The Oxford Time Travel series began with the novella The Fire Watch (1982), followed by the novels Doomsday Book (1992), To Say No to Dogs (1997), and the two-part series Blackout and All Clear (2010). All four works won the Hugo Award, and three won the Nebula Award (To Say No to Dogs was a finalist for the Nebula Award).

Considering that the Hugo Awards are chosen by popular vote among readers, while the Nebula Awards are decided by writers and critics, Connie Willis's series is a work that has received recognition from both readers and critics.

This series, which began with the 1982 novella "The Fire Watch," is set in the mid-21st century, when time travel has become possible, and deals with the events that unfold as the story travels back in time to the past, set in the Department of History at Oxford University in England.

When we look at novels that deal with time travel, we see that authors create and apply their own rules.

For example, Wells assumed the most liberal rule that could be allowed for time travel: that characters could visit the past and future without any restrictions.

Therefore, in "The Time Machine," the time traveler can act as he wishes, and the difficulties the protagonist encounters are merely devices to highlight the protagonist's abilities.

But Connie Willis enforces the strictest of time travel rules.

That is, due to the elasticity of space-time, it was assumed that a time traveler could never reverse causality, and even could not arrive at the desired space-time precisely due to deviation.

It was also assumed that no object could be brought or taken away that could potentially reverse causality (from this perspective, Colin's trip to the Middle Ages in Domesday Book with aspirin and a flashlight could be understood not as a misconception, but as a result of the fact that everyone around him was already dead, so nothing could be changed).

Therefore, the past is not a time of fools who are fooled by the present or future figures, but a time of equal relations, and the time traveler is limited to the role of a thorough observer who knows the outcome but cannot influence it in any way.

The Fire Watch, Doomsday Book, and Of Course the Dogs Were Based on These Basic Rules.

And in recent works like 『Blackout』 and 『All Clear』, this rule becomes more expanded and complex, assuming that deviations are not devices to prevent contradictions from occurring, but rather post-facto measures to resolve contradictions that have arisen.

This series has the important characteristic of recreating historical reality through extensive research, and for this reason, it can be said to be both science fiction and historical novel.

In fact, it took Connie Willis anywhere from five to eight years to complete each work, as she collected historical research.

Another characteristic of Connie Willis that runs through this series is his ability to do both comedy and tragedy.

It is common to find confessions that readers who first read the consistently cheerful "Dogs and All" with its comical yet serious atmosphere about the possibility of the universe being destroyed because of a cat were shocked by the endlessly dark development of "Doomsday Book" set during the Black Death, and there is even a conspiracy theory called "Connie Willis II" that there are separate writers of comedies and tragedies because of her writing style that freely crosses between comedy and tragedy.

His talent reaches its peak in 『Blackout』 and 『All Clear』, which provide the pleasure of reading through the exquisite combination of comedy and tragedy, the dialogue of characters and description of the period reminiscent of the works of Shakespeare, and the detailed plot setting like a mystery novel (as the author admits to being a mystery novel fan).

If there's one complaint readers have about this series as a whole, it's that Oxford in 2050-60 doesn't feel like a futuristic world at all.

For example, Oxford in 2054, as depicted in the novel Domesday Book, is not much different from the present, and in some ways is even behind in science and technology (think of 2054 without mobile phones).

However, if we consider that the purpose of science fiction is never to accurately predict the future through extrapolation, the inaccuracy of the science and technology of the future society depicted in this series cannot be a major flaw.

Rather, to borrow a phrase from Haruki Murakami, you could think of it as an alternative history novel about a world with time machines but no cell phones.

From John Bartholomew of The Fire Watch, who maintained an onlooker's attitude that he could not interfere with history in any way, to Kivrin of Doomsday Book, who tried to save people even though she knew it was impossible, to Verity and Ned of Of Course the Dog, who tried to correct their mistakes, fearing that their mistakes might change the outcome of the war, to Polly, Eileen, and Mike of Blackout and All Clear, who are now actively participating in history themselves, Connie Willis's works have continued to develop and change.

But what remains consistent through all these changes is that, as Polly answered Lord Godfrey's question, "Is it a comedy or a tragedy?" with "It is a comedy."

This is a part that clearly shows the love for humanity that Connie Willis has for humanity, who has published numerous works over the past 40 years since 1978 and has told stories of human courage and hope in all of her works.

Even back in 2000, when I was translating "The Dog Needs No Saying," I never imagined that I would end up doing this entire series over such a long period of time.

After that, I translated 『Doomsday Book』, and then, through connections, I translated 『The Fire Watch』, 『Blackout』, and 『All Clear』.

While the translation may not be free from mistranslations, I hope that this series will allow you to experience the bright light and beautiful scenery, and to eat and drink delicious grains and clear water.

- Choi Yong-jun

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: February 1, 2019

- Page count, weight, size: 1,136 pages | 1,226g | 137*197*70mm

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)