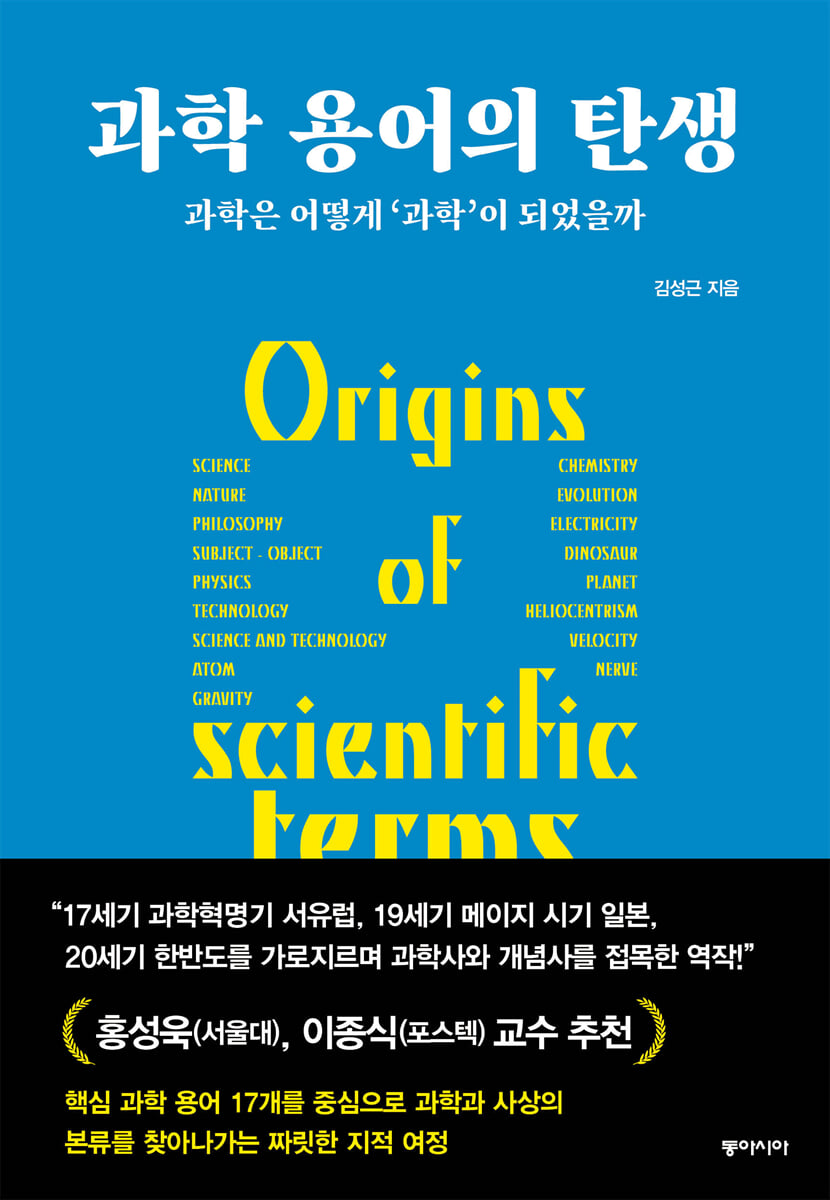

The Birth of Scientific Terminology

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

Modern science we have acceptedScience, nature, philosophy, subjective and objective, physics, technology, and even dinosaurs.

Most of the key concepts of Western-led modern science came through Japan.

This book goes one step further.

How did we perceive the words translated by Japan? A history of academic and scientific vocabulary compiled by a Korean scholar.

March 4, 2025. Natural Science PD Son Min-gyu

That's how 'science' began -

The romantic fantasy that language creates thought meets the history of science.

In East Asia, including Korea, the 'rainbow', which was once described as 'five-colored', became a 'seven-colored rainbow' after coming into contact with the Western concept of 'Sept couleurs de l'arc-en-ciel', which was influenced by Christian thought.

It is a shift in the rainbow paradigm.

The bold linguistic hypothesis that a person's thinking is governed by the language he or she uses was born more than 1,000 years ago and continues to subtly 'govern' our thinking to this day.

There has been much debate regarding this, but the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which was developed by Edward Sapir, a representative linguist who advocated this hypothesis, and his disciple Benjamin Lee Whorf, is not fully accepted today.

This is because the dominance-subordination relationship or causality between language and thought is not something that can be proven.

However, this hypothesis has not yet been completely rejected even in modern times, and remains somewhat lukewarm, suggesting that language and thought influence each other.

In fact, it is impossible for modern linguists to go back in time and observe the origins of language and the moment of birth of social culture.

But there is a language that can observe that moment.

These are ‘new words’ and ‘translated words.’

We often think 'scientifically' in our daily lives.

“?? is science,” he says, and “physically it is impossible.”

Distinguish between ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ and enjoy modern civilization created through ‘science and technology’.

When we say 'dinosaur', we all think of Tyrannosaurus Rex and other familiar creatures.

Memorize the order of the planets in the solar system, saying, 'Su, Geum, Ji, Hwa, Mok, To, Cheon, Hae (name).'

But when did this pattern of behavior begin? When did we begin to attribute a "scientific" quality to the word "science"? If we were to use the word "science" in conversation with someone from the Joseon Dynasty, they would likely interpret it entirely differently.

Before 'science' became established as a translation of science, science (科學) was an abbreviation of the study for the civil service examination, that is, the study of the civil service examination (科擧之學).

If you look at the list of classes at Wonsan Academy, which is considered the first science education institution in Korea, there is a subject called ‘Gyeokchi (格致)’.

This is a saying from the book “Gyeokmulchiji” (格物致知), which means “to investigate the principles of all things to the end and reach knowledge.”

What would this subject be like today? Of course, it's science.

It was a subject called science.

Various words, including 'gyeokchi', 'science', 'knowledge', 'academic', and 'academics', competed for the translation of 'science'.

In the end, what remained was 'science', but in fact, it wouldn't have been strange if someone had survived.

It is clear that the meaning of 'Gyeokchi', which we looked at earlier, is semantically related to what we mean by 'science' today.

Moreover, considering that the Latin word scientia, the etymology of science, meant a broad range of things such as 'knowledge' and 'knowledge', it is reasonable to question whether science has become 'science'.

But in the end, it was ‘science’ that survived.

No, it's science.

Science still lives on today and has a profound influence on many aspects of our thinking.

The author believes in the age-old idea that “language is the window to thought.”

Although language does not entirely govern our thinking, our thoughts are concretized through language, and human society is bound by language.

We discuss truth, understand science, and define life by sharing language.

However, not many people have explored the process through which such an important language came to be in its current form.

As a specialist in the history of science, the author explores the origins of many of the key scientific vocabulary we use today.

It traces how the framework of thought we 'inherit' was created and disseminated, and how its vocabulary has influenced the formation of our thought systems and worldview.

We cannot trace the vocabulary of the distant past beyond the limited sources and the vast time span.

However, it is possible to examine the process by which new vocabulary related to science was created and translated in modern times.

When we consider that as new vocabulary was translated and introduced, East Asian languages, cultures, and concepts inevitably served as receptors, it is also an observation of the friction that arose when Western scientific concepts encountered traditional East Asian thought.

And this was also a process of new birth in which different ideas collided to create the current system of thought, as Hegel talks about in dialectical thinking.

It is precisely this scene that we want to look into in this book.

The romantic fantasy that language creates thought meets the history of science.

In East Asia, including Korea, the 'rainbow', which was once described as 'five-colored', became a 'seven-colored rainbow' after coming into contact with the Western concept of 'Sept couleurs de l'arc-en-ciel', which was influenced by Christian thought.

It is a shift in the rainbow paradigm.

The bold linguistic hypothesis that a person's thinking is governed by the language he or she uses was born more than 1,000 years ago and continues to subtly 'govern' our thinking to this day.

There has been much debate regarding this, but the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which was developed by Edward Sapir, a representative linguist who advocated this hypothesis, and his disciple Benjamin Lee Whorf, is not fully accepted today.

This is because the dominance-subordination relationship or causality between language and thought is not something that can be proven.

However, this hypothesis has not yet been completely rejected even in modern times, and remains somewhat lukewarm, suggesting that language and thought influence each other.

In fact, it is impossible for modern linguists to go back in time and observe the origins of language and the moment of birth of social culture.

But there is a language that can observe that moment.

These are ‘new words’ and ‘translated words.’

We often think 'scientifically' in our daily lives.

“?? is science,” he says, and “physically it is impossible.”

Distinguish between ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ and enjoy modern civilization created through ‘science and technology’.

When we say 'dinosaur', we all think of Tyrannosaurus Rex and other familiar creatures.

Memorize the order of the planets in the solar system, saying, 'Su, Geum, Ji, Hwa, Mok, To, Cheon, Hae (name).'

But when did this pattern of behavior begin? When did we begin to attribute a "scientific" quality to the word "science"? If we were to use the word "science" in conversation with someone from the Joseon Dynasty, they would likely interpret it entirely differently.

Before 'science' became established as a translation of science, science (科學) was an abbreviation of the study for the civil service examination, that is, the study of the civil service examination (科擧之學).

If you look at the list of classes at Wonsan Academy, which is considered the first science education institution in Korea, there is a subject called ‘Gyeokchi (格致)’.

This is a saying from the book “Gyeokmulchiji” (格物致知), which means “to investigate the principles of all things to the end and reach knowledge.”

What would this subject be like today? Of course, it's science.

It was a subject called science.

Various words, including 'gyeokchi', 'science', 'knowledge', 'academic', and 'academics', competed for the translation of 'science'.

In the end, what remained was 'science', but in fact, it wouldn't have been strange if someone had survived.

It is clear that the meaning of 'Gyeokchi', which we looked at earlier, is semantically related to what we mean by 'science' today.

Moreover, considering that the Latin word scientia, the etymology of science, meant a broad range of things such as 'knowledge' and 'knowledge', it is reasonable to question whether science has become 'science'.

But in the end, it was ‘science’ that survived.

No, it's science.

Science still lives on today and has a profound influence on many aspects of our thinking.

The author believes in the age-old idea that “language is the window to thought.”

Although language does not entirely govern our thinking, our thoughts are concretized through language, and human society is bound by language.

We discuss truth, understand science, and define life by sharing language.

However, not many people have explored the process through which such an important language came to be in its current form.

As a specialist in the history of science, the author explores the origins of many of the key scientific vocabulary we use today.

It traces how the framework of thought we 'inherit' was created and disseminated, and how its vocabulary has influenced the formation of our thought systems and worldview.

We cannot trace the vocabulary of the distant past beyond the limited sources and the vast time span.

However, it is possible to examine the process by which new vocabulary related to science was created and translated in modern times.

When we consider that as new vocabulary was translated and introduced, East Asian languages, cultures, and concepts inevitably served as receptors, it is also an observation of the friction that arose when Western scientific concepts encountered traditional East Asian thought.

And this was also a process of new birth in which different ideas collided to create the current system of thought, as Hegel talks about in dialectical thinking.

It is precisely this scene that we want to look into in this book.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

preface

01.

science

The Japanese word 'science' (科學) meant 'the study of a branch' / Nishi Amane, Japan's first modern philosopher, translated science as 'hak' (學) / Science ultimately triumphs amidst various translations of science / The first Korean literature in which 'science' appeared was Yu Gil-jun's 'Seoyu Gyeonmun' in 1895 / The concept of 'science' by Jang Eung-jin, a Korean student studying in Japan / The word 'science' became popular in Joseon society

02.

nature

The first source of the Chinese character word '自然' is Lao Tzu's 'Tao Te Ching' / How did Edo-period Japanese scholars translate the Dutch word 'natuur'? / In the 19th century, the Chinese character word '自然' was used as a translation of 'natural' or 'naturally' / Nature, ultimately capturing 'nature' / Korea's traditional concept of 'nature' / Korean students studying in Japan accept the concept of 'nature' as 'a collection of external things' / The emergence of the term 'natural science'

03.

philosophy

Nishi Amane, who translated philosophy as '철학 (哲學)' / The word '철학' created to distinguish it from Confucianism / Japanese intellectuals who opposed the translated word '철학' / The spread of '철학' in Japan as a government-mandated word / The word '철학' appearing in Yu Gil-jun's '서유견문' / Philosophy is a science beyond science / The debate over old and new learning in Joseon around the 1910s and 'philosophy'

04.

Subjective-objective

Nishi Amane translates subjective as "this view" and objective as "the other view" / Why were subjectivity and objectivity separated in Nishi's philosophy? / 'Subjectivity' and 'Objectivity' after Nishi's philosophy / The myth of 'objectivity' and scientific imperialism / When did 'subjectivity' and 'objectivity' enter Korea, and how were they used?

05.

physics

The term "physics" used in East Asia before the modern era meant "the way or principle of things" / The unprecedented and bizarre incident called "Gungni" / Nishi Amane's concept of physics / Nishi Amane's "Hakuhakyeonhwan" and "Gyeokmulhak" / The Meiji government's institutionalization of science and the vocabulary of "physics" / The establishment of the "Physics Translation Society" in 1883 / How was the concept of "physics" as a natural science accepted in Korea? / Kim Du-bong, who advocated changing the word "physics" to the Korean word "Mongyeolgal"

06.

technology

How did technology meet science? / The etymology of technology / The concept of 'technology' in traditional East Asia / Nishi Amane's 'technology' and 'art' / The Meiji government and the introduction of modern industrial technology / Translations of technology in modern Japanese dictionaries / Yu Gil-jun's concept of 'technology' meaning industrial technology / Translations of technology and art in Korean dictionaries / Distinctions between crafts, industry, technology, and art

07.

science and technology

The term "science and technology" emerged under Japan's wartime mobilization system in the 1940s / The term "science and technology" first appeared in Korea / The term "science and technology" in Korea after liberation

08.

atom

Tadao Shizuki's 'atom' and 'vacuum' / Reinterpreting atoms as qi / How did pre-modern East Asians translate 'atom' and 'vacuum'? / 19th-century Japanese scholars who translated the smallest particle as 'molecule' / Who coined the word 'atom' and when? / When did 'atom' and 'vacuum' first come into use in Korea?

09.

gravitation

Shizuki's 'old calendar' meant gravity / Changing 'old calendar' to 'gravity' and 'gravitation' / The concepts of 'gravity' and 'universal gravitation' in the Meiji era / How did 'gravity' appear in Korea?

10.

chemistry

The word 'chemistry' first appeared in China / The counterattack of the Japanese translation 'samil' / The Chinese word 'chemistry' is transmitted to Japan / Nishi Amane's 'chemistry' / The tenacious survival of the word 'samil' / When and how was 'chemistry' introduced to Korea?

11.

evolution

The Japanese word 'evolution' first appeared in the 1878 『Gakuyejirim』 / China's Enfu chose the translation 'natural' / Social Darwinism that swept Japan in the late 19th century / The vocabulary 'natural selection' and 'survival of the fittest' that shook modern East Asia / The word 'evolution' in Korea

12.

electricity

The Chinese word 'electricity' was created in China / In Japan, the Dutch word 'elektriciteit' initially meant 'vessel' / The Chinese word 'electricity' was imported to Japan / The word 'socket' of unknown origin / The word 'electricity' was imported to Korea / Electric lights were turned on in Gyeongbokgung Palace and Geoncheonggung Palace on March 6, 1887

13.

dinosaur

The word 'dinosaur' was coined by Richard Owen in 1842 / Matajiro Yokoyama, who first coined the word 'dinosaur' / When did Koreans first learn about 'dinosaur'?

14.

planet

Why is it called a planet in Korea and a planet in Japan? / Neptune was almost called 'Dragon King' / How did 'planet' survive in Korea?

15.

heliocentrism

In search of the first source of the term 'geocentric theory' / Yoshio Nanko, the first person to use the term 'geocentric theory' / The geocentric theory in China / The term 'geocentric theory' in Korea

16.

speed

Aristotle's Physics and 'Speed' / The distinction between 'Speed' and 'Velocity' was made in the 19th century / Translations of 'Momentum' and 'Force' / Nishi Amane, who first coined the term 'Speed' / How was velocity translated in China? / 'Speed' and 'Velocity' in Korean literature

17.

nerves

Western medicine and 'nerve' encountered by the Chinese / Genpaku Sugita, who first coined the word 'nerve' = the path of the gods / The spread of the word 'nerve' in Japan around the Meiji period / The word 'brain' created by Western missionaries in China / In Korean dictionaries at the end of the Joseon Dynasty, nerve was mainly translated as 'tendon' / The first Korean literature in which the word 'nerve' appeared was 『Hansung Sunbo』

Conclusion

annotation

preface

01.

science

The Japanese word 'science' (科學) meant 'the study of a branch' / Nishi Amane, Japan's first modern philosopher, translated science as 'hak' (學) / Science ultimately triumphs amidst various translations of science / The first Korean literature in which 'science' appeared was Yu Gil-jun's 'Seoyu Gyeonmun' in 1895 / The concept of 'science' by Jang Eung-jin, a Korean student studying in Japan / The word 'science' became popular in Joseon society

02.

nature

The first source of the Chinese character word '自然' is Lao Tzu's 'Tao Te Ching' / How did Edo-period Japanese scholars translate the Dutch word 'natuur'? / In the 19th century, the Chinese character word '自然' was used as a translation of 'natural' or 'naturally' / Nature, ultimately capturing 'nature' / Korea's traditional concept of 'nature' / Korean students studying in Japan accept the concept of 'nature' as 'a collection of external things' / The emergence of the term 'natural science'

03.

philosophy

Nishi Amane, who translated philosophy as '철학 (哲學)' / The word '철학' created to distinguish it from Confucianism / Japanese intellectuals who opposed the translated word '철학' / The spread of '철학' in Japan as a government-mandated word / The word '철학' appearing in Yu Gil-jun's '서유견문' / Philosophy is a science beyond science / The debate over old and new learning in Joseon around the 1910s and 'philosophy'

04.

Subjective-objective

Nishi Amane translates subjective as "this view" and objective as "the other view" / Why were subjectivity and objectivity separated in Nishi's philosophy? / 'Subjectivity' and 'Objectivity' after Nishi's philosophy / The myth of 'objectivity' and scientific imperialism / When did 'subjectivity' and 'objectivity' enter Korea, and how were they used?

05.

physics

The term "physics" used in East Asia before the modern era meant "the way or principle of things" / The unprecedented and bizarre incident called "Gungni" / Nishi Amane's concept of physics / Nishi Amane's "Hakuhakyeonhwan" and "Gyeokmulhak" / The Meiji government's institutionalization of science and the vocabulary of "physics" / The establishment of the "Physics Translation Society" in 1883 / How was the concept of "physics" as a natural science accepted in Korea? / Kim Du-bong, who advocated changing the word "physics" to the Korean word "Mongyeolgal"

06.

technology

How did technology meet science? / The etymology of technology / The concept of 'technology' in traditional East Asia / Nishi Amane's 'technology' and 'art' / The Meiji government and the introduction of modern industrial technology / Translations of technology in modern Japanese dictionaries / Yu Gil-jun's concept of 'technology' meaning industrial technology / Translations of technology and art in Korean dictionaries / Distinctions between crafts, industry, technology, and art

07.

science and technology

The term "science and technology" emerged under Japan's wartime mobilization system in the 1940s / The term "science and technology" first appeared in Korea / The term "science and technology" in Korea after liberation

08.

atom

Tadao Shizuki's 'atom' and 'vacuum' / Reinterpreting atoms as qi / How did pre-modern East Asians translate 'atom' and 'vacuum'? / 19th-century Japanese scholars who translated the smallest particle as 'molecule' / Who coined the word 'atom' and when? / When did 'atom' and 'vacuum' first come into use in Korea?

09.

gravitation

Shizuki's 'old calendar' meant gravity / Changing 'old calendar' to 'gravity' and 'gravitation' / The concepts of 'gravity' and 'universal gravitation' in the Meiji era / How did 'gravity' appear in Korea?

10.

chemistry

The word 'chemistry' first appeared in China / The counterattack of the Japanese translation 'samil' / The Chinese word 'chemistry' is transmitted to Japan / Nishi Amane's 'chemistry' / The tenacious survival of the word 'samil' / When and how was 'chemistry' introduced to Korea?

11.

evolution

The Japanese word 'evolution' first appeared in the 1878 『Gakuyejirim』 / China's Enfu chose the translation 'natural' / Social Darwinism that swept Japan in the late 19th century / The vocabulary 'natural selection' and 'survival of the fittest' that shook modern East Asia / The word 'evolution' in Korea

12.

electricity

The Chinese word 'electricity' was created in China / In Japan, the Dutch word 'elektriciteit' initially meant 'vessel' / The Chinese word 'electricity' was imported to Japan / The word 'socket' of unknown origin / The word 'electricity' was imported to Korea / Electric lights were turned on in Gyeongbokgung Palace and Geoncheonggung Palace on March 6, 1887

13.

dinosaur

The word 'dinosaur' was coined by Richard Owen in 1842 / Matajiro Yokoyama, who first coined the word 'dinosaur' / When did Koreans first learn about 'dinosaur'?

14.

planet

Why is it called a planet in Korea and a planet in Japan? / Neptune was almost called 'Dragon King' / How did 'planet' survive in Korea?

15.

heliocentrism

In search of the first source of the term 'geocentric theory' / Yoshio Nanko, the first person to use the term 'geocentric theory' / The geocentric theory in China / The term 'geocentric theory' in Korea

16.

speed

Aristotle's Physics and 'Speed' / The distinction between 'Speed' and 'Velocity' was made in the 19th century / Translations of 'Momentum' and 'Force' / Nishi Amane, who first coined the term 'Speed' / How was velocity translated in China? / 'Speed' and 'Velocity' in Korean literature

17.

nerves

Western medicine and 'nerve' encountered by the Chinese / Genpaku Sugita, who first coined the word 'nerve' = the path of the gods / The spread of the word 'nerve' in Japan around the Meiji period / The word 'brain' created by Western missionaries in China / In Korean dictionaries at the end of the Joseon Dynasty, nerve was mainly translated as 'tendon' / The first Korean literature in which the word 'nerve' appeared was 『Hansung Sunbo』

Conclusion

annotation

Detailed image

Into the book

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the English word science (French word science) appeared as early as the mid-14th century.

But at that time, this vocabulary was far from today's science.

It meant 'knowing' or 'knowledge in general', like the Latin 'scientiae'.

If we look for a word in the literature of that time that is close to what we understand today as science, it is not the English word science or the Latin word scientia, but rather the word 'natural philosophy philosophiæ naturalis'.

Moreover, people called such explorers natural philosophers, virtuosos, savant, etc.

For example, Isaac Newton wrote a Latin work called Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), also known as Principia, in 1687, and as the title suggests, he called his discipline "natural philosophy" rather than "science."

--- From 「01ㆍScience/科學/Science」

Lee Man-gyu revealed that linguist Lee Yun-jae had gone to Shanghai and written down some of the scientific vocabulary created by Kim Du-bong, and introduced about 521 terms related to physics, chemistry, and mathematics written in pure Korean.

For example, Kim Du-bong wrote physics as 'mon-gyeol-gal', mechanics as 'him-gal', movement as 'eom-jeok', inertia as 'beor-haeng', gravity as 'jeojae-him', universal gravitation as 'da-it-geul-him', centripetal force as 'sok-chat-him', and centrifugal force as 'sok-tteu-him'.

Kim Du-bong's proposal was very meaningful in that it looked back at the problem of foreign words that had been accepted almost uncritically during the modernization process and sought to replace them with pure Korean words.

--- From 「05ㆍPhysics/Physics」

The Latin word 'ars' (English art) is closer to today's technology and was actively used until the early modern period.

However, with the development of capitalism, as mechanical industries grew beyond the traditional craftsmanship, it became necessary to distinguish art in factories or production sites from art as a traditional discipline, art, or handicraft.

That is, a new term, ‘mechanical art’, has emerged within the field of art.

Peter Ramus, a 16th-century French philosopher and educational reformer, divided art into liberal art and mechanical art, and used the Latin word technologia as an umbrella term for them.

Nowadays, technology is usually translated as 'skill', but traditionally, the Chinese character '技術' had a different meaning.

That is, the earliest example of the Chinese character 技術 can be found in the first section of the “Biographies of the Traders” in Sima Qian’s “Records of the Grand Historian” (around 91 BC).

This is a passage that says, “The reason why doctors, radiologist, and other technicians who make a living exert their talents to the fullest while striving for spiritual well-being is because they value food.”

The "Hwasik Yeoljeon" of the "Records of the Grand Historian" introduces each country's agricultural, fishery, and commerce products, as well as industrial fields such as iron and steel, metallurgy, and foundry. In the above sentence, "technology" meant the "skill" or "talent" of doctors and magicians.

--- From 「06ㆍTechnology/技術/Technology」

The following year, February 24, 1908, in the 18th issue of the Taegeuk Hakbo titled “Injogeum,” it states, “The theory that all matter is made of extremely fine dust is still widely popular today, and they call this fine dust an atom and advocate monism, but this is nothing more than a speculation [Is the theory that all matter is made of extremely fine dust still prevalent today? Why give this fine dust the name of an atom and advocate monism? Is this not a single theory?”

The term "mijin" (微塵), which was originally a traditional Buddhist term, is used here to mean "atom," indicating that atomism is nothing but nonsense.

--- From "08ㆍAtom"

Unlike the English word dinosaur, which means 'a frighteningly large lizard', the Chinese character for dinosaur means 'a fearsome dragon'.

Matajiro, like Goto, translated saurus as 'dragon' and added the character 'gong' (fearful) in front of it to create a new translation, 'dinosaur'.

However, there were some who preferred the translation that was more faithful to the original concept of the word, 'fearfully great lizard', coined by Owen, rather than the word 'dinosaur' coined by Matajiro.

And instead of 'dinosaur', they used the word 'Gongcheok-fear?' or 'Gongseok-fear?'

'Gongcheok' or 'Gongseok' are Chinese characters that refer to lizards, 'Domagyeom Cheok?' or 'Domagyeom Seok?', and the character 'Gong', meaning 'fearful', is added to them.

--- From "13ㆍDinosaur/恐龍/Dinosaur"

These five planets are also associated with ancient Chinese philosophy.

The Five Elements Theory is a representative example.

This theory of the five elements, which states that everything in the world is made up of five substances: fire, water, wood, metal, and earth, developed through their mutual correspondence with the five planets.

It is also well known that these five planets and seven celestial bodies, including the sun and moon, formed the basis of Eastern and Western cosmology, calendars, and alchemy.

The names of the days of the week for the 7th are representative.

Sunday corresponds to the Sun, Monday corresponds to the Moon, Tuesday corresponds to Mars, Wednesday corresponds to Mercury, Thursday corresponds to Jupiter, Friday corresponds to Venus, and Saturday corresponds to Saturn.

The calendar called 'Chiljeongsan', created in 1442 during the reign of King Sejong, is a record of the movements of these seven celestial bodies.

--- From "14ㆍPlane"

You might ask, wouldn't the confusion go away if we translated speed as velocity and velocity as speed?

But the problem is not that simple.

Some argue that it is more appropriate to change speed to velocity and velocity to speed.

Because the degree of speed refers to the ‘degree of doing something’, and the force of velocity refers to the ‘power of doing something’.

Therefore, etymologically, the 'do' of 'speed' indicates 'the degree of something', like temperature, density, and humidity, so it is closer to a scalar value that only indicates size, whereas the 'force' of speed, that is, force, is more appropriate to express as a vector value because the direction in which it acts is important.

But at that time, this vocabulary was far from today's science.

It meant 'knowing' or 'knowledge in general', like the Latin 'scientiae'.

If we look for a word in the literature of that time that is close to what we understand today as science, it is not the English word science or the Latin word scientia, but rather the word 'natural philosophy philosophiæ naturalis'.

Moreover, people called such explorers natural philosophers, virtuosos, savant, etc.

For example, Isaac Newton wrote a Latin work called Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), also known as Principia, in 1687, and as the title suggests, he called his discipline "natural philosophy" rather than "science."

--- From 「01ㆍScience/科學/Science」

Lee Man-gyu revealed that linguist Lee Yun-jae had gone to Shanghai and written down some of the scientific vocabulary created by Kim Du-bong, and introduced about 521 terms related to physics, chemistry, and mathematics written in pure Korean.

For example, Kim Du-bong wrote physics as 'mon-gyeol-gal', mechanics as 'him-gal', movement as 'eom-jeok', inertia as 'beor-haeng', gravity as 'jeojae-him', universal gravitation as 'da-it-geul-him', centripetal force as 'sok-chat-him', and centrifugal force as 'sok-tteu-him'.

Kim Du-bong's proposal was very meaningful in that it looked back at the problem of foreign words that had been accepted almost uncritically during the modernization process and sought to replace them with pure Korean words.

--- From 「05ㆍPhysics/Physics」

The Latin word 'ars' (English art) is closer to today's technology and was actively used until the early modern period.

However, with the development of capitalism, as mechanical industries grew beyond the traditional craftsmanship, it became necessary to distinguish art in factories or production sites from art as a traditional discipline, art, or handicraft.

That is, a new term, ‘mechanical art’, has emerged within the field of art.

Peter Ramus, a 16th-century French philosopher and educational reformer, divided art into liberal art and mechanical art, and used the Latin word technologia as an umbrella term for them.

Nowadays, technology is usually translated as 'skill', but traditionally, the Chinese character '技術' had a different meaning.

That is, the earliest example of the Chinese character 技術 can be found in the first section of the “Biographies of the Traders” in Sima Qian’s “Records of the Grand Historian” (around 91 BC).

This is a passage that says, “The reason why doctors, radiologist, and other technicians who make a living exert their talents to the fullest while striving for spiritual well-being is because they value food.”

The "Hwasik Yeoljeon" of the "Records of the Grand Historian" introduces each country's agricultural, fishery, and commerce products, as well as industrial fields such as iron and steel, metallurgy, and foundry. In the above sentence, "technology" meant the "skill" or "talent" of doctors and magicians.

--- From 「06ㆍTechnology/技術/Technology」

The following year, February 24, 1908, in the 18th issue of the Taegeuk Hakbo titled “Injogeum,” it states, “The theory that all matter is made of extremely fine dust is still widely popular today, and they call this fine dust an atom and advocate monism, but this is nothing more than a speculation [Is the theory that all matter is made of extremely fine dust still prevalent today? Why give this fine dust the name of an atom and advocate monism? Is this not a single theory?”

The term "mijin" (微塵), which was originally a traditional Buddhist term, is used here to mean "atom," indicating that atomism is nothing but nonsense.

--- From "08ㆍAtom"

Unlike the English word dinosaur, which means 'a frighteningly large lizard', the Chinese character for dinosaur means 'a fearsome dragon'.

Matajiro, like Goto, translated saurus as 'dragon' and added the character 'gong' (fearful) in front of it to create a new translation, 'dinosaur'.

However, there were some who preferred the translation that was more faithful to the original concept of the word, 'fearfully great lizard', coined by Owen, rather than the word 'dinosaur' coined by Matajiro.

And instead of 'dinosaur', they used the word 'Gongcheok-fear?' or 'Gongseok-fear?'

'Gongcheok' or 'Gongseok' are Chinese characters that refer to lizards, 'Domagyeom Cheok?' or 'Domagyeom Seok?', and the character 'Gong', meaning 'fearful', is added to them.

--- From "13ㆍDinosaur/恐龍/Dinosaur"

These five planets are also associated with ancient Chinese philosophy.

The Five Elements Theory is a representative example.

This theory of the five elements, which states that everything in the world is made up of five substances: fire, water, wood, metal, and earth, developed through their mutual correspondence with the five planets.

It is also well known that these five planets and seven celestial bodies, including the sun and moon, formed the basis of Eastern and Western cosmology, calendars, and alchemy.

The names of the days of the week for the 7th are representative.

Sunday corresponds to the Sun, Monday corresponds to the Moon, Tuesday corresponds to Mars, Wednesday corresponds to Mercury, Thursday corresponds to Jupiter, Friday corresponds to Venus, and Saturday corresponds to Saturn.

The calendar called 'Chiljeongsan', created in 1442 during the reign of King Sejong, is a record of the movements of these seven celestial bodies.

--- From "14ㆍPlane"

You might ask, wouldn't the confusion go away if we translated speed as velocity and velocity as speed?

But the problem is not that simple.

Some argue that it is more appropriate to change speed to velocity and velocity to speed.

Because the degree of speed refers to the ‘degree of doing something’, and the force of velocity refers to the ‘power of doing something’.

Therefore, etymologically, the 'do' of 'speed' indicates 'the degree of something', like temperature, density, and humidity, so it is closer to a scalar value that only indicates size, whereas the 'force' of speed, that is, force, is more appropriate to express as a vector value because the direction in which it acts is important.

--- From 「16ㆍSpeed/Speed/Velocity」

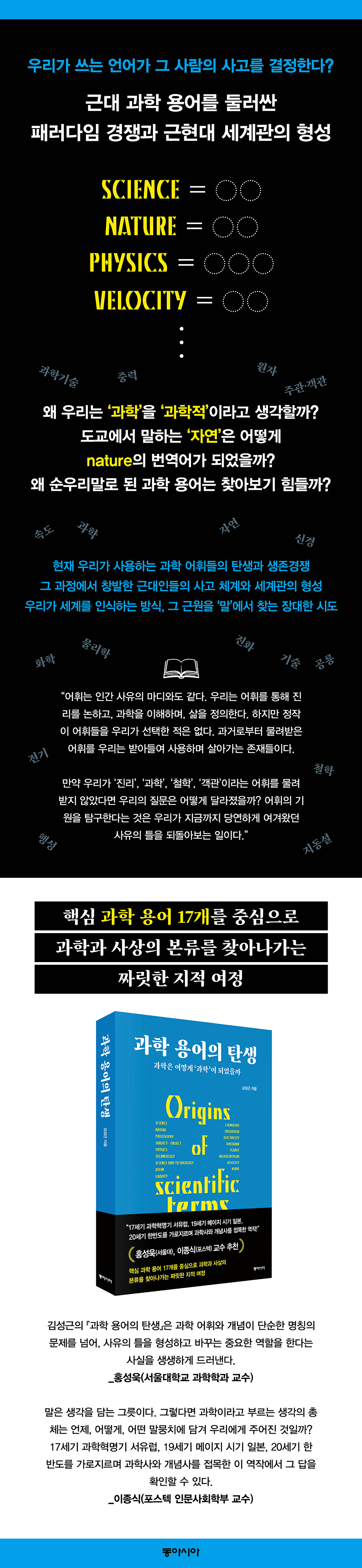

Publisher's Review

By observing the paradigm competition of vocabulary

We can understand how that vocabulary works in our thought system.

What is science? What is physics? What is philosophy? It may seem like a Zen question, but few people can readily give a clear, immediate answer when asked such questions.

We often use 'scientific' terms in our daily lives.

In a way, this could be said to be the result of the modernization process that made reason and rationality the common good that our society should pursue.

Rational over emotional, scientific over magical, objective over subjective.

So what exactly is this "scientific" thing we consider "better"? Dictionary definitions of science are readily available, and examples can be used to illustrate what constitutes scientific practice. But there's a more precise way to explore the essence of science.

It's about going back to the beginning and finding out what we started calling 'science'.

Perhaps this is not so much the essence of science as the essence of what we define as science.

“It seems that people often think that it is impossible to find and write all scientific terms in Korean, and that they can only be pronounced as they are in Western or Chinese characters.

But scientific terms are nothing special.

“It is made by inserting the name of an invented person or place name, and it is made according to the nature, shape, movement, source, use, etc. of the object. If we look at the word elements hidden in the predicate like this, there is absolutely no need to worry about not being able to find the predicate due to a lack of Korean.”

Lee Man-gyu, "Scientific Terminology and the Korean Language"

In this book, the author tells the story of Lee Man-gyu and Kim Du-bong, who attempted to replace scientific terms with pure Korean words.

If you were to ask modern people today, most would likely accept scientific terms like science, physics, planets, and dinosaurs as being 'as such', but there was a fierce paradigm competition over these too.

As Lee Man-gyu says, scientific terms were also determined by humans for their convenience, and there was no absolute standard.

Nevertheless, why did scientific terminology settle into its current form? By exploring this process, we can delve into the essence of the terminology.

For example, let's think about a planet.

If you immediately thought of the translation 'planet', then you are faithfully following the scientific thinking system commonly used in Korea.

Despite being part of the same Chinese character cultural sphere, Japan uses the word '惑星' as a translation for 'planet'.

On the other hand, despite having adopted many scientific terms from Japan, the word 'planet' is rarely used in our country.

It is said that the reason why the word 惑 used in Japan has meanings such as 'wandering' or 'losing one's way', but in Korea, it is mostly used in the sense of 'to be troubled' rather than in that sense.

However, as can be seen from the meaning of 'wandering', the word 'planet' is also a coined word that implies that a celestial body does not stay in one place but moves.

If you look at the etymology, it has something in common with the word ‘planet.’

As scientific terms are translated, coordination occurs in the process of using words that already existed in each society as receptors.

If we go back through this process, each term has its own reason and justification for its creation.

That is precisely the essence we give to the term.

That is, it is a manifestation of our thinking.

It is this process of competition that the author explores in this book.

From the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century, through Meiji Japan, to the Korean Peninsula, scientific terms have undergone constant competition to become what they are today.

What is established through this is not simply the existence of individual terms, but our current scientific thinking system itself, which has been built through changes in the scientific paradigm.

This is the framework of thought we share now.

This book is an intellectual journey that seeks to dismantle and examine the framework of such thinking.

Gyeokchi, Gungri, Mongyeolgal, Samil, Yongwangseong, Sachung, Gongseok, Gongcheok…

How would we have thought if other vocabulary had survived?

The competitive process of each scientific term introduced by the author in this book was by no means smooth.

Each term survived by competing with countless alternatives, and the process was not inevitable, but rather there was a decisive moment until it seemed somewhat irrational, such as a preemptive effect due to chance or simple chronological order, or the adoption of a controlled term.

If you think of it as words written on paper, it seems extremely static, but at the same time, the process of this competition is extremely dynamic.

It may seem like a pointless fantasy now, but it is only natural to think, “What if this word had survived?” while reading this book.

Even though there is no scientific basis for this, in popular culture, dinosaurs and dragons are often linked.

But would that have happened even if we hadn't translated "dinosaur" as "공룡(恐龍)"? The author provides more details in the book, but the meaning of "dinosaur" is closer to the English meaning of "fearfully great, a lizard."

If this meaning had been preserved, it is highly likely that the word 'Gongcheok (恐?)' or 'Gongseok (恐?)' would have survived instead of 'Dinosaur (恐?)'.

It is a combination of the Chinese characters for lizard, ‘lizard chuck(?)’ or ‘lizard stone(?)’, and the character for fear, ‘gong’.

If that had happened, wouldn't our current fears and admiration for dinosaurs have diminished somewhat? In this book, the author traces the evolution of scientific terminology, examining the remnants of obsolete vocabulary whose meanings are now difficult to discern.

The process is tedious but never boring.

This is not simply a stuffed animal displaying the corpse of language, but a dynamic adventure exploring the roots of our shared perceptions and thoughts.

We can understand how that vocabulary works in our thought system.

What is science? What is physics? What is philosophy? It may seem like a Zen question, but few people can readily give a clear, immediate answer when asked such questions.

We often use 'scientific' terms in our daily lives.

In a way, this could be said to be the result of the modernization process that made reason and rationality the common good that our society should pursue.

Rational over emotional, scientific over magical, objective over subjective.

So what exactly is this "scientific" thing we consider "better"? Dictionary definitions of science are readily available, and examples can be used to illustrate what constitutes scientific practice. But there's a more precise way to explore the essence of science.

It's about going back to the beginning and finding out what we started calling 'science'.

Perhaps this is not so much the essence of science as the essence of what we define as science.

“It seems that people often think that it is impossible to find and write all scientific terms in Korean, and that they can only be pronounced as they are in Western or Chinese characters.

But scientific terms are nothing special.

“It is made by inserting the name of an invented person or place name, and it is made according to the nature, shape, movement, source, use, etc. of the object. If we look at the word elements hidden in the predicate like this, there is absolutely no need to worry about not being able to find the predicate due to a lack of Korean.”

Lee Man-gyu, "Scientific Terminology and the Korean Language"

In this book, the author tells the story of Lee Man-gyu and Kim Du-bong, who attempted to replace scientific terms with pure Korean words.

If you were to ask modern people today, most would likely accept scientific terms like science, physics, planets, and dinosaurs as being 'as such', but there was a fierce paradigm competition over these too.

As Lee Man-gyu says, scientific terms were also determined by humans for their convenience, and there was no absolute standard.

Nevertheless, why did scientific terminology settle into its current form? By exploring this process, we can delve into the essence of the terminology.

For example, let's think about a planet.

If you immediately thought of the translation 'planet', then you are faithfully following the scientific thinking system commonly used in Korea.

Despite being part of the same Chinese character cultural sphere, Japan uses the word '惑星' as a translation for 'planet'.

On the other hand, despite having adopted many scientific terms from Japan, the word 'planet' is rarely used in our country.

It is said that the reason why the word 惑 used in Japan has meanings such as 'wandering' or 'losing one's way', but in Korea, it is mostly used in the sense of 'to be troubled' rather than in that sense.

However, as can be seen from the meaning of 'wandering', the word 'planet' is also a coined word that implies that a celestial body does not stay in one place but moves.

If you look at the etymology, it has something in common with the word ‘planet.’

As scientific terms are translated, coordination occurs in the process of using words that already existed in each society as receptors.

If we go back through this process, each term has its own reason and justification for its creation.

That is precisely the essence we give to the term.

That is, it is a manifestation of our thinking.

It is this process of competition that the author explores in this book.

From the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century, through Meiji Japan, to the Korean Peninsula, scientific terms have undergone constant competition to become what they are today.

What is established through this is not simply the existence of individual terms, but our current scientific thinking system itself, which has been built through changes in the scientific paradigm.

This is the framework of thought we share now.

This book is an intellectual journey that seeks to dismantle and examine the framework of such thinking.

Gyeokchi, Gungri, Mongyeolgal, Samil, Yongwangseong, Sachung, Gongseok, Gongcheok…

How would we have thought if other vocabulary had survived?

The competitive process of each scientific term introduced by the author in this book was by no means smooth.

Each term survived by competing with countless alternatives, and the process was not inevitable, but rather there was a decisive moment until it seemed somewhat irrational, such as a preemptive effect due to chance or simple chronological order, or the adoption of a controlled term.

If you think of it as words written on paper, it seems extremely static, but at the same time, the process of this competition is extremely dynamic.

It may seem like a pointless fantasy now, but it is only natural to think, “What if this word had survived?” while reading this book.

Even though there is no scientific basis for this, in popular culture, dinosaurs and dragons are often linked.

But would that have happened even if we hadn't translated "dinosaur" as "공룡(恐龍)"? The author provides more details in the book, but the meaning of "dinosaur" is closer to the English meaning of "fearfully great, a lizard."

If this meaning had been preserved, it is highly likely that the word 'Gongcheok (恐?)' or 'Gongseok (恐?)' would have survived instead of 'Dinosaur (恐?)'.

It is a combination of the Chinese characters for lizard, ‘lizard chuck(?)’ or ‘lizard stone(?)’, and the character for fear, ‘gong’.

If that had happened, wouldn't our current fears and admiration for dinosaurs have diminished somewhat? In this book, the author traces the evolution of scientific terminology, examining the remnants of obsolete vocabulary whose meanings are now difficult to discern.

The process is tedious but never boring.

This is not simply a stuffed animal displaying the corpse of language, but a dynamic adventure exploring the roots of our shared perceptions and thoughts.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: February 14, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 372 pages | 500g | 146*211*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788962626438

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)