I want to die in peace

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

I want to die like a human beingModern human death resembles that of livestock.

He died after going back and forth between home and hospital without his consent.

To borrow the expression of this book, we are destined to move on the 'conveyor belt of medicine.'

Is it possible to face death with dignity and agency? Medical anthropologists and hospice doctors explored alternatives.

December 13, 2024. Humanities PD Son Min-gyu

Why Are Our Deaths Becoming More and More Poor?

The Way to a 'Peaceful Death' Discovered at Hospice

Consulting and appearance on EBS Documentary Prime's "Where is My Last Home?"

Highly recommended by novelist Choi Jin-young and reporter Jang Il-ho

In today's Korean society, the end of life brings about anxiety and even fear rather than stability and comfort.

Many people often get lost and stumble between meaningless life-prolonging treatment and radical euthanasia.

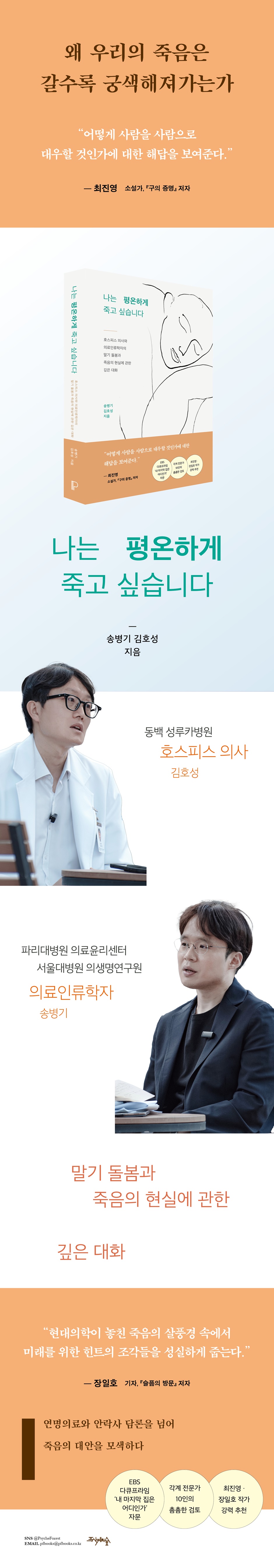

In this book, two young intellectuals, medical anthropologist Song Byeong-gi and hospice doctor Kim Ho-seong, calmly observe this dizzying reality.

The book places hospice at the center of the book and examines the realities of terminal care and death faced by Korean society from various angles.

We selected six keywords (space, food, terminal diagnosis, symptoms, care, and mourning) and held several conversations over the course of two years. Based on the transcripts, we meticulously supplemented them with new writing and numerous other materials.

It explores the topic of hospice and death from a multifaceted perspective, including vivid field experiences and episodes, institutional analysis, cross-cultural perspectives, historical review, and anthropological exploration.

It presents hospice practices in a rich context and explores alternatives to death that go beyond the treatment-centered paradigm.

The Way to a 'Peaceful Death' Discovered at Hospice

Consulting and appearance on EBS Documentary Prime's "Where is My Last Home?"

Highly recommended by novelist Choi Jin-young and reporter Jang Il-ho

In today's Korean society, the end of life brings about anxiety and even fear rather than stability and comfort.

Many people often get lost and stumble between meaningless life-prolonging treatment and radical euthanasia.

In this book, two young intellectuals, medical anthropologist Song Byeong-gi and hospice doctor Kim Ho-seong, calmly observe this dizzying reality.

The book places hospice at the center of the book and examines the realities of terminal care and death faced by Korean society from various angles.

We selected six keywords (space, food, terminal diagnosis, symptoms, care, and mourning) and held several conversations over the course of two years. Based on the transcripts, we meticulously supplemented them with new writing and numerous other materials.

It explores the topic of hospice and death from a multifaceted perspective, including vivid field experiences and episodes, institutional analysis, cross-cultural perspectives, historical review, and anthropological exploration.

It presents hospice practices in a rich context and explores alternatives to death that go beyond the treatment-centered paradigm.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

preface

Part 1: Back in the World of Life

Chapter 1 Space

Into the hospice

Life and death are gently connected

Is a single room always better?

Have a wedding ceremony at a hospital

Photos, cafes, and life

Patients going on a picnic in the garden

There are no wall clocks in the hospice.

The story of life continues

I hope there will be more colorful spaces

A different way of life called hospice

Chapter 2 Food

How much can you eat?

Memories of food, food of memories

The misconception that eating well will make you feel better

Why We're Obsessed with Sap and Supplements

The Nose Dilemma

Good intentions sometimes require caution.

Hospitality for the Poor

Part 2 Through Pain

Chapter 3 Terminal Diagnosis

The difficulty of drawing a line

wandering non-cancerous patients

The paradox of medical technological progress

The law's dream for the terminal stage

See the reality beyond the legal provisions

Who dares to speak out?

Patients are also living everyday lives.

Chapter 4 Symptoms

What is pain

First priority: pain relief

Using narcotic painkillers

A storm of meaning is coming

Healthy social distancing

There's a plan for everything, even care.

About delirium

Palliative care and ethics

Three Perspectives on Suffering

From pain to solidarity

Part 3: Remaking Death

Chapter 5 Care

There is no daily life without care.

Bathing, the pinnacle of care

Treat as a human being

For the patient's comfort

Expand your senses and mental space

The Work of a Hospice Nurse

So the care becomes smaller

A remote island with no money and only rocks

A country where aging becomes a nuisance

What Makes Care Possible

Chapter 6: Mourning

The last scene of a certain life

Following the patient's body

Caring for the carer

Why is hospice care so difficult?

What happens after death

What is a truly good death?

The cycle of care connecting life and death

Hospice: A New Imagination of Death

Conclusion

Reviews

Acknowledgements

main

References

Part 1: Back in the World of Life

Chapter 1 Space

Into the hospice

Life and death are gently connected

Is a single room always better?

Have a wedding ceremony at a hospital

Photos, cafes, and life

Patients going on a picnic in the garden

There are no wall clocks in the hospice.

The story of life continues

I hope there will be more colorful spaces

A different way of life called hospice

Chapter 2 Food

How much can you eat?

Memories of food, food of memories

The misconception that eating well will make you feel better

Why We're Obsessed with Sap and Supplements

The Nose Dilemma

Good intentions sometimes require caution.

Hospitality for the Poor

Part 2 Through Pain

Chapter 3 Terminal Diagnosis

The difficulty of drawing a line

wandering non-cancerous patients

The paradox of medical technological progress

The law's dream for the terminal stage

See the reality beyond the legal provisions

Who dares to speak out?

Patients are also living everyday lives.

Chapter 4 Symptoms

What is pain

First priority: pain relief

Using narcotic painkillers

A storm of meaning is coming

Healthy social distancing

There's a plan for everything, even care.

About delirium

Palliative care and ethics

Three Perspectives on Suffering

From pain to solidarity

Part 3: Remaking Death

Chapter 5 Care

There is no daily life without care.

Bathing, the pinnacle of care

Treat as a human being

For the patient's comfort

Expand your senses and mental space

The Work of a Hospice Nurse

So the care becomes smaller

A remote island with no money and only rocks

A country where aging becomes a nuisance

What Makes Care Possible

Chapter 6: Mourning

The last scene of a certain life

Following the patient's body

Caring for the carer

Why is hospice care so difficult?

What happens after death

What is a truly good death?

The cycle of care connecting life and death

Hospice: A New Imagination of Death

Conclusion

Reviews

Acknowledgements

main

References

Detailed image

Into the book

[Song Byeong-gi] When I arrived at the entrance, I encountered an unexpected scene.

People took off their shoes.

It felt strange.

I thought I was taking off my shoes for hygiene reasons, but it also felt like I was entering someone's house.

Looking at the various types of shoes placed in the spacious hallway, I wondered what kind of people might be there.

I took off my shoes, and strangely enough, I felt a little more at ease.

--- p.35

[Kim Ho-seong] Basically, single rooms are comfortable and convenient.

However, we experience that this is not the case for all patients.

Sometimes, you even go to a single room and then move back to a double room.

It has its own special characteristics.

For example, in a double room, one patient may have limited mobility, but the other patient may be in good physical condition. In this case, the patient in better condition will take care of the patient next to him.

“Nurse, this patient is sick.

Something like, “Come and take a look.”

--- p.43

[Song Byeong-gi] The most striking thing about this hospital room is the large window.

The sunlight is bright and the scenery is so clear that it seems as if it could be captured.

You can see a small mountain in front of the hospice, and next to it you can see a road and apartments.

You can also see people relaxing in the garden on the first floor.

(Omitted) In other words, the hospice space seeks to be connected to the patient's network of relationships represented by home and daily life.

As a space where life and death are gently connected.

The patient is in the hospital room, but he is not a disconnected entity.

--- p.44~45

[Kim Ho-seong] The program room is a meeting space for the multidisciplinary team, where patients receive various therapies such as music and art therapy, and where events take place.

For us who live our daily lives, an event means something special, but for patients admitted to hospice, it means a return to their previous daily lives.

For example, things like celebrating the birthday of a patient or guardian.

One time, we even had a small wedding.

The daughter and father, each dressed in a dress and a tuxedo, entered in front of the mother who was lying on the bed, and the groom entered.

The guests and nurses all gathered and applauded.

It was a touching scene.

--- p.47

[Song Byeong-gi] I conducted field research at a nursing home in Paris where elderly people suffering from degenerative neurological diseases gathered.

(Omitted) For them, the start of the day depended on what clothes they wore, what speed they moved at, what place they went to, what sound they heard, and who they met – in other words, their overall sense.

Just because they have poor memories, repeat the same actions, wander, and speak nonsense, does that mean their lives are worthless? Is it right to judge them based on whether they're sane or not? Shouldn't we instead see them as living their lives with a different sense?

--- p.64~65

[Kim Ho-seong] Of course, alcohol is prohibited in hospitals.

This is because, in addition to addiction, the patient is actually administered multiple medications, which can affect liver function.

(Omitted) However, the patient had cancer in the brain, not in another organ, and his liver function was fine.

Even if I were to drink again, I thought I would only drink a small amount.

So I gave permission.

I think that small amounts of alcohol can be given to patients who do not have much time left, as long as it is meaningful and does not cause obvious harm.

--- p.82~83

[Song Byeong-gi] Food is connected to the narrative of life.

It's no coincidence that some people say that pajeon and makgeolli are 'really good' on a rainy day.

This is only possible if you had the experience and enjoyed it, heard that the experience was good, or felt that the experience would be good.

People believe that experiences, memories, and knowledge about eating are imprinted in the 'body' rather than the 'head'.

(Omitted) Food is connected to understanding and respecting the continuity of life.

--- p.87~88

[Kim Ho-seong] Because cancer is invisible to patients and their guardians, they often blame food for their loss of energy.

In their view, the biggest reason for the decline in physical strength is the decrease in the amount of food consumed.

So, they eat more than the patient's capacity, or feed more.

And that's where the problem arises.

It can cause pneumonia or abdominal pain.

So, the medical staff always emphasize this during the interview.

In hospice, people eat for quality of life, not for energy recovery.

--- p.93

[Song Byeong-gi] Even though my daughter-in-law is a medical professional and is in charge of nursing, it was difficult for her to give an honest opinion about artificial nutrition for patients.

If you bring that up for no reason, you might be morally criticized for saying, “Do you wish your in-laws would die soon?”

The medical staff, knowing the circumstances, looked for the 'son' when making 'important medical decisions'.

Medical decisions within hospice are closely linked to family and gender issues.

--- p.114

[Kim Ho-seong] Stories of people like Scott Nearing and Zen monks ending their lives comfortably through voluntary fasting are often cited as 'ideal' examples.

However, if you look at the literature, the process of fasting is not always smooth.

There are reports that the physical pain of patients, such as thirst and delirium, is not insignificant, and that it also causes a lot of ethical guilt among medical staff who watch it.

Moreover, in Korea, the Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment stipulates that even if life-sustaining treatment is refused, basic hydration and nutrition must be provided.

--- p.119

[Song Byeong-gi] The patient says he goes to the facility to avoid causing trouble to his family, the family says they have no choice but to find various ways to ensure the patient's safety, and the medical staff says they have to prevent and respond to emergency situations.

As if each person was fighting individually, they were each carrying out their respective responsibilities at the time.

However, within that very ‘ethics’, the existing structure that makes patients vulnerable and ahistorical is firmly maintained.

Families, caregivers, and medical staff also struggle to provide care in some way, often under vulnerable conditions, and become exhausted.

Why are we forced to experience care in this way?

--- p.132

[Song Byeong-gi] In the case of terminally ill patients who cannot enter hospice, life-sustaining treatment can only be discontinued if two or more doctors determine that the patient has entered the terminal stage.

The problem, as we have seen, is that it is clinically very difficult to distinguish between the terminal and end-of-life stages.

The End-of-Life Treatment Decisions Act clearly states that the terminal stage is a “state of imminent death,” but common sense tells us that it is not easy to define “how imminent death is.”

Should we say "one minute before death"? Or "one hour before"? Or "24 hours before"? Or "one year before"? Above all, I question whether it's appropriate to measure the end of life in such quantitative terms.

--- p.148

[Kim Ho-seong] It's a law that's hard to find abroad.

In most countries, the right to self-determination of terminally ill patients is left to the judgment of on-site medical staff and their relationship with the patient.

However, Korea has been going through many legal cases and has been restrictively approving the relationship between doctors and patients through complicated and cumbersome 'laws' rather than the autonomous relationship between doctors and patients.

There is also a historical context in which these laws were created, and it is also bittersweet that they seem to show a cross-section of a 'low-trust society.'

--- p.153

[Song Byeong-gi] There are various forms of life, and the form of the family is also changing rapidly.

It is no exaggeration to say that now, a single-person household, rather than a four-person household, is the 'normal family'.

There are many only children, and many people who have lost their parents and live alone.

There are also many people who live in unmarried single-person households, same-sex couples, or cohabiting relationships.

However, in such cases, even if you have a close relationship with the patient, it is difficult to participate in life-sustaining treatment decisions on his behalf.

--- p.158

[Kim Ho-seong] Of course, doctors play an important role in reducing the physical difficulties of patients.

But from the perspective of one person's life, I'm not sure if being a doctor is the most important thing.

(Omitted) For patients with chronic or terminal illnesses, rather than acute illnesses, the role of doctors is not as great as expected.

In this case, the quality of care is relatively more important than medical treatment.

Questions like, “Should I have surgery after I’m over eighty?” and “Should I really get cancer screenings at ninety?” are necessary.

--- p.176

[Song Byeong-gi] Pain cannot be summarized as a disease.

There is also 'suffering' that patients experience physically.

For example, the musculoskeletal disorders experienced by caregivers and nursing assistants cannot be understood solely through biomedical systems.

Their suffering is closely related to their relationships with patients and their caregivers, harsh working conditions, social perceptions of care, and the health insurance and long-term care insurance systems for the elderly.

(Omitted) In short, ‘pain’ is a intersection of biological order and social order.

--- p.183

[Kim Ho-seong] The medical staff must quickly control this pain.

Only then can the next work of hospice begin.

When pain control is not effective, patients invariably say, “I don’t want to live like this,” or “I want to die as soon as possible.”

First of all, if the patient's pain is not controlled, it is difficult for the hospice multidisciplinary team to even approach them.

The patient's psychological difficulties, the existential meaning of life, and family relationships all become secondary issues in the face of pain.

Therefore, pain control is the most important prerequisite for starting the role of the multidisciplinary team.

--- p.184

[Song Byeong-gi] I don't think the reason patients are sick is just because of the disease.

Aren't "urgent" encounters between patients and medical staff, "easy" touching of the patient's body, and situations where the patient's story is treated "shabby" all contributing to the patient's pain? Care takes time.

A time for patients and medical staff to talk and get to know each other.

--- p.196~197

[Kim Ho-seong] Usually, when the pain subsides, the pain of your past life that was hidden for a long time appears, and you are soon faced with a storm of 'meaning'.

Now that life is running out, the proposition that we must spend the remaining time meaningfully suddenly arises.

But the problem is that many people don't know how to spend that time.

“Yeah, I need to spend the remaining time meaningfully.

But what should I do?”

--- p.201

[Song Byeong-gi] If you have lived for a long time according to the imperative of 'being healthy', you might be confused about what to say at a hospice.

In that respect, I think hospice is a kind of language school.

The multidisciplinary team studies the language of patients and their caregivers, and patients and caregivers learn another language of life.

Above all, I believe it is important for patients, guardians, and the multidisciplinary team to 'practice' communication with each other.

--- p.201~202

[Kim Ho-seong] I think the more fundamental and important thing in the field is to alleviate the inevitable and inevitable pain of patients as much as possible and, in the process, create beauty created by chance and fleeting moments.

A pleasant old story that I happened to share while exchanging dry snippets of conversation with a caregiver, or the fragrant coffee that momentarily makes me forget the lonely life that no one visits the hospital.

--- p.206

[Song Byeong-gi] Without proper communication between the patient, guardian, and multidisciplinary team, palliative sedation can seem like a "slow euthanasia."

Of course, as mentioned earlier, the goals of euthanasia and palliative sedation are clearly different.

Nevertheless, even if palliative sedation does not hasten the patient's death, it can make the patient appear to be dead.

In this context, we can imagine the anxiety and concerns of patients, guardians, and medical staff.

--- p.228

[Kim Ho-seong] The faces of patients who have been struggling with illness for a long time become clear after bathing, and their hair becomes refreshed and free of oil.

When I make rounds, I see that the patient is very soft.

Some patients are a little tired and fall asleep.

Patients' greatest feeling of welcome at hospice probably comes after taking a bath.

Volunteers are happy to see such patients.

We are also beings who feel the meaning and joy of life when we see others happy because of us.

--- p.258~259

[Song Byeong-gi] I still remember a scene I happened to see recently while passing through the corridor of a clinic at a university hospital.

A doctor opened the door to his examination room wide and examined a patient.

But as soon as the patient enters the examination room, the doctor starts talking to him in a scolding tone.

Your blood test results are bad, you need to lose weight, you shouldn't eat meat, etc.

The patient, who appeared to be middle-aged, remained still as if he had committed a sin.

The doctor's words were probably medically correct.

The doctor would have given the patient loving advice.

Still, did the doctor really have to talk like that with the office door open? Moreover, did the doctor have no choice but to establish a relationship with the patient through such words? Many questions arose.

--- p.269

[Kim Ho-seong] But realistically, there are difficulties.

One patient said, “I don’t feel any meaning in life.

When someone says, "I want to die quickly," who can truly say, "This is the meaning of your life?" It's someone else's life.

We can help a little by finding clues, but ultimately, the patient has to think and make their own decisions.

The multidisciplinary team is the people who are by the patient's side.

The question of 'how much help should we give?' or, from the patient's perspective, 'how much should we rely on them?' is always a difficult one.

It's also our limitation.

So, for spiritual matters, we turn to priests and nuns for help.

--- p.282~283

[Song Byeong-gi] What's notable is that the hospital's pursuit of profit maximization and patients' preference for cutting-edge technology are intertwined.

As can be easily seen in the mass media, hospitals popular with patients are those equipped with 'famous doctors' who are good at diagnosis and treatment and with cutting-edge medical equipment.

Given this reality, it is no surprise that hospice care is unpopular with patients.

Care hovers on the margins of healthcare.

It is considered to be something with low marketability, something whose effectiveness is difficult to measure, something secondary, or something that individuals do on their own.

--- p.296

[Kim Ho-seong] I recently watched a Japanese film called “Plan 75.”

The story is that if elderly people over the age of 75 promise to die, the state will pay them money and even provide euthanasia and cremation.

My heart was complicated as I thought about the reality of terminal care in Korea throughout the movie.

What also surprised me was the story the film's director heard while interviewing fifteen elderly Japanese people while writing the script.

The director was surprised by the unexpectedly large number of elderly people who responded, “I wish there was such a system,” and “I would feel reassured if it actually existed.”

Old people recognized that growing old was a miserable thing and a burden to their families and society.

--- p.306~307

[Song Byeong-gi] Medical knowledge about death is growing exponentially, and people are easily accessing that knowledge through various media.

The problem is not the quantity and accessibility of knowledge about death, but its content and form.

Today, discourse about death is commonly used as discourse against death.

For example, medical knowledge about lifestyles, symptoms, and diseases that 'hasten' death is used to 'delay' death.

It's not that that way of knowing is bad.

However, I am pointing out that this particular way of knowing can paradoxically narrow the scope of our understanding of death.

--- p.321

[Kim Ho-seong] The timing of hospice transfer is the most important factor in a patient's quality of life.

As I've mentioned several times, the decline in physical strength in terminally ill cancer patients is almost always rapid.

So, if a patient is transferred to hospice care in the late stages of instability or at the end of life, there is little improvement in the quality of life.

The focus is simply on caring for the guardians.

Sometimes, there are repeated instances where patients are sent from higher-level hospitals too late.

That's really no different from thinking of hospice as a so-called 'place to die'.

It is not helpful to the patient and their guardian, nor to the multidisciplinary team.

This is because multidisciplinary teams continue to burn out as they care for caregivers who are not yet ready for death.

That's what it means to not take proper care of the patient.

--- p.329~330

[Song Byeong-gi] According to statistics from 2021, the number of deaths from diseases eligible for hospice care was 89,000, but only about 19,000 of them used hospice care.

The utilization rate is only about 21 percent.

(Omitted) There are a total of 88 hospice wards nationwide, 35 of which are concentrated in the metropolitan area, while there is only one in Ulsan Metropolitan City and Jeju Island, and none in Sejong City.

In this reality, talking about why people don't go to hospice or are reluctant to go there feels like a play on the absurd.

--- p.334~335

[Kim Ho-seong] Sometimes, there are patients who pass away as if they are really asleep. If you change their clothes, it seems like they are really asleep.

When I wear my regular clothes, I feel like I'm just sleeping in bed.

Then, the caregivers can avoid taking their last impression of the patient as simply a loss.

It's like saying, 'I'm still alive', 'This is not the end'.

And this affects future mourning.

Because we remember that person's last appearance as wearing what he or she usually wore.

--- p.342

[Song Byeong-gi] There is a sanctuary in front of the entrance on the first floor of Dongbaek St. Luke's Hospital, and the names of the dead are written on the wall next to the sanctuary.

As people enter and leave the hospice, they encounter the names of the dead.

Looking at the names of those who died like this, wouldn't we realize that they were not simply "terminal patients," but individuals with distinct personalities? In short, this intertwining of objects, rituals, memories, and imaginations urges us not to dismiss death as a personal event or an intimate experience, but rather to view it as a social relationship involving the dying and their caregivers, the dead and the living.

--- p.358

[Kim Ho-seong] We must accurately and continuously discuss the value of hospice palliative care.

We need to actively promote what usefulness it has.

(Omitted) I still think there is an opportunity in Korea.

But if we don't prepare now, I think we're going to face a really big crisis.

When we are hit head-on by the unprecedented wave of aging, the influx of patients with various diseases and terminal illnesses, without thorough preparation, Korean society will experience unprecedented suffering.

We need to understand the value of hospice palliative care and establish a reality.

People took off their shoes.

It felt strange.

I thought I was taking off my shoes for hygiene reasons, but it also felt like I was entering someone's house.

Looking at the various types of shoes placed in the spacious hallway, I wondered what kind of people might be there.

I took off my shoes, and strangely enough, I felt a little more at ease.

--- p.35

[Kim Ho-seong] Basically, single rooms are comfortable and convenient.

However, we experience that this is not the case for all patients.

Sometimes, you even go to a single room and then move back to a double room.

It has its own special characteristics.

For example, in a double room, one patient may have limited mobility, but the other patient may be in good physical condition. In this case, the patient in better condition will take care of the patient next to him.

“Nurse, this patient is sick.

Something like, “Come and take a look.”

--- p.43

[Song Byeong-gi] The most striking thing about this hospital room is the large window.

The sunlight is bright and the scenery is so clear that it seems as if it could be captured.

You can see a small mountain in front of the hospice, and next to it you can see a road and apartments.

You can also see people relaxing in the garden on the first floor.

(Omitted) In other words, the hospice space seeks to be connected to the patient's network of relationships represented by home and daily life.

As a space where life and death are gently connected.

The patient is in the hospital room, but he is not a disconnected entity.

--- p.44~45

[Kim Ho-seong] The program room is a meeting space for the multidisciplinary team, where patients receive various therapies such as music and art therapy, and where events take place.

For us who live our daily lives, an event means something special, but for patients admitted to hospice, it means a return to their previous daily lives.

For example, things like celebrating the birthday of a patient or guardian.

One time, we even had a small wedding.

The daughter and father, each dressed in a dress and a tuxedo, entered in front of the mother who was lying on the bed, and the groom entered.

The guests and nurses all gathered and applauded.

It was a touching scene.

--- p.47

[Song Byeong-gi] I conducted field research at a nursing home in Paris where elderly people suffering from degenerative neurological diseases gathered.

(Omitted) For them, the start of the day depended on what clothes they wore, what speed they moved at, what place they went to, what sound they heard, and who they met – in other words, their overall sense.

Just because they have poor memories, repeat the same actions, wander, and speak nonsense, does that mean their lives are worthless? Is it right to judge them based on whether they're sane or not? Shouldn't we instead see them as living their lives with a different sense?

--- p.64~65

[Kim Ho-seong] Of course, alcohol is prohibited in hospitals.

This is because, in addition to addiction, the patient is actually administered multiple medications, which can affect liver function.

(Omitted) However, the patient had cancer in the brain, not in another organ, and his liver function was fine.

Even if I were to drink again, I thought I would only drink a small amount.

So I gave permission.

I think that small amounts of alcohol can be given to patients who do not have much time left, as long as it is meaningful and does not cause obvious harm.

--- p.82~83

[Song Byeong-gi] Food is connected to the narrative of life.

It's no coincidence that some people say that pajeon and makgeolli are 'really good' on a rainy day.

This is only possible if you had the experience and enjoyed it, heard that the experience was good, or felt that the experience would be good.

People believe that experiences, memories, and knowledge about eating are imprinted in the 'body' rather than the 'head'.

(Omitted) Food is connected to understanding and respecting the continuity of life.

--- p.87~88

[Kim Ho-seong] Because cancer is invisible to patients and their guardians, they often blame food for their loss of energy.

In their view, the biggest reason for the decline in physical strength is the decrease in the amount of food consumed.

So, they eat more than the patient's capacity, or feed more.

And that's where the problem arises.

It can cause pneumonia or abdominal pain.

So, the medical staff always emphasize this during the interview.

In hospice, people eat for quality of life, not for energy recovery.

--- p.93

[Song Byeong-gi] Even though my daughter-in-law is a medical professional and is in charge of nursing, it was difficult for her to give an honest opinion about artificial nutrition for patients.

If you bring that up for no reason, you might be morally criticized for saying, “Do you wish your in-laws would die soon?”

The medical staff, knowing the circumstances, looked for the 'son' when making 'important medical decisions'.

Medical decisions within hospice are closely linked to family and gender issues.

--- p.114

[Kim Ho-seong] Stories of people like Scott Nearing and Zen monks ending their lives comfortably through voluntary fasting are often cited as 'ideal' examples.

However, if you look at the literature, the process of fasting is not always smooth.

There are reports that the physical pain of patients, such as thirst and delirium, is not insignificant, and that it also causes a lot of ethical guilt among medical staff who watch it.

Moreover, in Korea, the Act on Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment stipulates that even if life-sustaining treatment is refused, basic hydration and nutrition must be provided.

--- p.119

[Song Byeong-gi] The patient says he goes to the facility to avoid causing trouble to his family, the family says they have no choice but to find various ways to ensure the patient's safety, and the medical staff says they have to prevent and respond to emergency situations.

As if each person was fighting individually, they were each carrying out their respective responsibilities at the time.

However, within that very ‘ethics’, the existing structure that makes patients vulnerable and ahistorical is firmly maintained.

Families, caregivers, and medical staff also struggle to provide care in some way, often under vulnerable conditions, and become exhausted.

Why are we forced to experience care in this way?

--- p.132

[Song Byeong-gi] In the case of terminally ill patients who cannot enter hospice, life-sustaining treatment can only be discontinued if two or more doctors determine that the patient has entered the terminal stage.

The problem, as we have seen, is that it is clinically very difficult to distinguish between the terminal and end-of-life stages.

The End-of-Life Treatment Decisions Act clearly states that the terminal stage is a “state of imminent death,” but common sense tells us that it is not easy to define “how imminent death is.”

Should we say "one minute before death"? Or "one hour before"? Or "24 hours before"? Or "one year before"? Above all, I question whether it's appropriate to measure the end of life in such quantitative terms.

--- p.148

[Kim Ho-seong] It's a law that's hard to find abroad.

In most countries, the right to self-determination of terminally ill patients is left to the judgment of on-site medical staff and their relationship with the patient.

However, Korea has been going through many legal cases and has been restrictively approving the relationship between doctors and patients through complicated and cumbersome 'laws' rather than the autonomous relationship between doctors and patients.

There is also a historical context in which these laws were created, and it is also bittersweet that they seem to show a cross-section of a 'low-trust society.'

--- p.153

[Song Byeong-gi] There are various forms of life, and the form of the family is also changing rapidly.

It is no exaggeration to say that now, a single-person household, rather than a four-person household, is the 'normal family'.

There are many only children, and many people who have lost their parents and live alone.

There are also many people who live in unmarried single-person households, same-sex couples, or cohabiting relationships.

However, in such cases, even if you have a close relationship with the patient, it is difficult to participate in life-sustaining treatment decisions on his behalf.

--- p.158

[Kim Ho-seong] Of course, doctors play an important role in reducing the physical difficulties of patients.

But from the perspective of one person's life, I'm not sure if being a doctor is the most important thing.

(Omitted) For patients with chronic or terminal illnesses, rather than acute illnesses, the role of doctors is not as great as expected.

In this case, the quality of care is relatively more important than medical treatment.

Questions like, “Should I have surgery after I’m over eighty?” and “Should I really get cancer screenings at ninety?” are necessary.

--- p.176

[Song Byeong-gi] Pain cannot be summarized as a disease.

There is also 'suffering' that patients experience physically.

For example, the musculoskeletal disorders experienced by caregivers and nursing assistants cannot be understood solely through biomedical systems.

Their suffering is closely related to their relationships with patients and their caregivers, harsh working conditions, social perceptions of care, and the health insurance and long-term care insurance systems for the elderly.

(Omitted) In short, ‘pain’ is a intersection of biological order and social order.

--- p.183

[Kim Ho-seong] The medical staff must quickly control this pain.

Only then can the next work of hospice begin.

When pain control is not effective, patients invariably say, “I don’t want to live like this,” or “I want to die as soon as possible.”

First of all, if the patient's pain is not controlled, it is difficult for the hospice multidisciplinary team to even approach them.

The patient's psychological difficulties, the existential meaning of life, and family relationships all become secondary issues in the face of pain.

Therefore, pain control is the most important prerequisite for starting the role of the multidisciplinary team.

--- p.184

[Song Byeong-gi] I don't think the reason patients are sick is just because of the disease.

Aren't "urgent" encounters between patients and medical staff, "easy" touching of the patient's body, and situations where the patient's story is treated "shabby" all contributing to the patient's pain? Care takes time.

A time for patients and medical staff to talk and get to know each other.

--- p.196~197

[Kim Ho-seong] Usually, when the pain subsides, the pain of your past life that was hidden for a long time appears, and you are soon faced with a storm of 'meaning'.

Now that life is running out, the proposition that we must spend the remaining time meaningfully suddenly arises.

But the problem is that many people don't know how to spend that time.

“Yeah, I need to spend the remaining time meaningfully.

But what should I do?”

--- p.201

[Song Byeong-gi] If you have lived for a long time according to the imperative of 'being healthy', you might be confused about what to say at a hospice.

In that respect, I think hospice is a kind of language school.

The multidisciplinary team studies the language of patients and their caregivers, and patients and caregivers learn another language of life.

Above all, I believe it is important for patients, guardians, and the multidisciplinary team to 'practice' communication with each other.

--- p.201~202

[Kim Ho-seong] I think the more fundamental and important thing in the field is to alleviate the inevitable and inevitable pain of patients as much as possible and, in the process, create beauty created by chance and fleeting moments.

A pleasant old story that I happened to share while exchanging dry snippets of conversation with a caregiver, or the fragrant coffee that momentarily makes me forget the lonely life that no one visits the hospital.

--- p.206

[Song Byeong-gi] Without proper communication between the patient, guardian, and multidisciplinary team, palliative sedation can seem like a "slow euthanasia."

Of course, as mentioned earlier, the goals of euthanasia and palliative sedation are clearly different.

Nevertheless, even if palliative sedation does not hasten the patient's death, it can make the patient appear to be dead.

In this context, we can imagine the anxiety and concerns of patients, guardians, and medical staff.

--- p.228

[Kim Ho-seong] The faces of patients who have been struggling with illness for a long time become clear after bathing, and their hair becomes refreshed and free of oil.

When I make rounds, I see that the patient is very soft.

Some patients are a little tired and fall asleep.

Patients' greatest feeling of welcome at hospice probably comes after taking a bath.

Volunteers are happy to see such patients.

We are also beings who feel the meaning and joy of life when we see others happy because of us.

--- p.258~259

[Song Byeong-gi] I still remember a scene I happened to see recently while passing through the corridor of a clinic at a university hospital.

A doctor opened the door to his examination room wide and examined a patient.

But as soon as the patient enters the examination room, the doctor starts talking to him in a scolding tone.

Your blood test results are bad, you need to lose weight, you shouldn't eat meat, etc.

The patient, who appeared to be middle-aged, remained still as if he had committed a sin.

The doctor's words were probably medically correct.

The doctor would have given the patient loving advice.

Still, did the doctor really have to talk like that with the office door open? Moreover, did the doctor have no choice but to establish a relationship with the patient through such words? Many questions arose.

--- p.269

[Kim Ho-seong] But realistically, there are difficulties.

One patient said, “I don’t feel any meaning in life.

When someone says, "I want to die quickly," who can truly say, "This is the meaning of your life?" It's someone else's life.

We can help a little by finding clues, but ultimately, the patient has to think and make their own decisions.

The multidisciplinary team is the people who are by the patient's side.

The question of 'how much help should we give?' or, from the patient's perspective, 'how much should we rely on them?' is always a difficult one.

It's also our limitation.

So, for spiritual matters, we turn to priests and nuns for help.

--- p.282~283

[Song Byeong-gi] What's notable is that the hospital's pursuit of profit maximization and patients' preference for cutting-edge technology are intertwined.

As can be easily seen in the mass media, hospitals popular with patients are those equipped with 'famous doctors' who are good at diagnosis and treatment and with cutting-edge medical equipment.

Given this reality, it is no surprise that hospice care is unpopular with patients.

Care hovers on the margins of healthcare.

It is considered to be something with low marketability, something whose effectiveness is difficult to measure, something secondary, or something that individuals do on their own.

--- p.296

[Kim Ho-seong] I recently watched a Japanese film called “Plan 75.”

The story is that if elderly people over the age of 75 promise to die, the state will pay them money and even provide euthanasia and cremation.

My heart was complicated as I thought about the reality of terminal care in Korea throughout the movie.

What also surprised me was the story the film's director heard while interviewing fifteen elderly Japanese people while writing the script.

The director was surprised by the unexpectedly large number of elderly people who responded, “I wish there was such a system,” and “I would feel reassured if it actually existed.”

Old people recognized that growing old was a miserable thing and a burden to their families and society.

--- p.306~307

[Song Byeong-gi] Medical knowledge about death is growing exponentially, and people are easily accessing that knowledge through various media.

The problem is not the quantity and accessibility of knowledge about death, but its content and form.

Today, discourse about death is commonly used as discourse against death.

For example, medical knowledge about lifestyles, symptoms, and diseases that 'hasten' death is used to 'delay' death.

It's not that that way of knowing is bad.

However, I am pointing out that this particular way of knowing can paradoxically narrow the scope of our understanding of death.

--- p.321

[Kim Ho-seong] The timing of hospice transfer is the most important factor in a patient's quality of life.

As I've mentioned several times, the decline in physical strength in terminally ill cancer patients is almost always rapid.

So, if a patient is transferred to hospice care in the late stages of instability or at the end of life, there is little improvement in the quality of life.

The focus is simply on caring for the guardians.

Sometimes, there are repeated instances where patients are sent from higher-level hospitals too late.

That's really no different from thinking of hospice as a so-called 'place to die'.

It is not helpful to the patient and their guardian, nor to the multidisciplinary team.

This is because multidisciplinary teams continue to burn out as they care for caregivers who are not yet ready for death.

That's what it means to not take proper care of the patient.

--- p.329~330

[Song Byeong-gi] According to statistics from 2021, the number of deaths from diseases eligible for hospice care was 89,000, but only about 19,000 of them used hospice care.

The utilization rate is only about 21 percent.

(Omitted) There are a total of 88 hospice wards nationwide, 35 of which are concentrated in the metropolitan area, while there is only one in Ulsan Metropolitan City and Jeju Island, and none in Sejong City.

In this reality, talking about why people don't go to hospice or are reluctant to go there feels like a play on the absurd.

--- p.334~335

[Kim Ho-seong] Sometimes, there are patients who pass away as if they are really asleep. If you change their clothes, it seems like they are really asleep.

When I wear my regular clothes, I feel like I'm just sleeping in bed.

Then, the caregivers can avoid taking their last impression of the patient as simply a loss.

It's like saying, 'I'm still alive', 'This is not the end'.

And this affects future mourning.

Because we remember that person's last appearance as wearing what he or she usually wore.

--- p.342

[Song Byeong-gi] There is a sanctuary in front of the entrance on the first floor of Dongbaek St. Luke's Hospital, and the names of the dead are written on the wall next to the sanctuary.

As people enter and leave the hospice, they encounter the names of the dead.

Looking at the names of those who died like this, wouldn't we realize that they were not simply "terminal patients," but individuals with distinct personalities? In short, this intertwining of objects, rituals, memories, and imaginations urges us not to dismiss death as a personal event or an intimate experience, but rather to view it as a social relationship involving the dying and their caregivers, the dead and the living.

--- p.358

[Kim Ho-seong] We must accurately and continuously discuss the value of hospice palliative care.

We need to actively promote what usefulness it has.

(Omitted) I still think there is an opportunity in Korea.

But if we don't prepare now, I think we're going to face a really big crisis.

When we are hit head-on by the unprecedented wave of aging, the influx of patients with various diseases and terminal illnesses, without thorough preparation, Korean society will experience unprecedented suffering.

We need to understand the value of hospice palliative care and establish a reality.

--- p.366

Publisher's Review

Beyond the discourse of meaningless life-prolonging treatment and radical euthanasia

Seeking Alternatives to Death Today

“How to treat people as people

“It shows the answer.”

Choi Jin-young (novelist, author of "Proof of the Sphere")

Death is painful, but the process of dying is even more painful.

Because the process of dying in a hospital is not so easy.

It's not easy to sacrifice daily life for intensive treatment at a large hospital, but it's also not easy to endure the gloom that slowly eats away at one's life as one moves back and forth between nursing homes and convalescent hospitals.

Many people in Korean society are so aware of this fact that they are consumed by a desire to escape the pain, a “desire to die cleanly” (p. 9).

It is in this context that the so-called pro-euthanasia opinion appears to be around 80% in opinion polls.

But is this the only way to escape suffering? Shouldn't we explore alternatives before making a convenient, yet risky, choice? Could it be that we're obsessed with efficiency, even when it comes to death? While the two authors of this book fully agree that the face of death today needs to change, they believe we should seek a slower, more nuanced approach, rather than a hasty one.

A process of death that relieves the patient's suffering while also being considered complete by both the guardian and the hospital staff.

It is not too late to think about simple and so-called clean means later.

With this problem in mind, what the authors are focusing on is 'hospice'.

This book, focusing on hospice, provides a stark reflection on the reality of terminal care and death in Korean society today.

Hospice is commonly known as a place where terminally ill cancer patients spend the last days of their lives.

Medical anthropologist Song Byeong-gi and hospice doctor Kim Ho-seong go beyond this simple impression and meticulously examine, based on their respective expertise, what hospice does, how it operates, and its institutional and systematic characteristics.

It explores the topic of hospice and death through a multi-faceted lens, including vivid field experiences and episodes, institutional analysis, cross-cultural perspectives, historical review, and anthropological exploration.

The authors selected six keywords (space, food, terminal diagnosis, symptoms, care, and grief) and held several conversations over the course of two years. Based on the transcripts, they meticulously supplemented the book with new writing and numerous other materials.

By presenting it in a conversational format rather than narrative prose, the authors' mutual understanding is clearly revealed, while also facilitating easy understanding for readers.

It is particularly noteworthy that it is a hospice story that deals with the Korean situation and Korean questions.

This book presents hospice practices in a rich context as a response to “neither letting patients die nor leaving them to die” (p. 369), and explores alternatives to death that go beyond the treatment-centered paradigm.

“In the midst of the death scene that modern medicine has missed,

“I diligently gather pieces of hints for the future.”

Jang Il-ho (journalist, author of "A Visit from Sadness")

Why a 'peaceful death'?

The main goal of hospice is the physical, psychological, and social 'comfort' of the patient.

To make the patient's body and mind comfortable, we administer medication, provide nutrition, provide counseling, and implement various therapies.

The value of patient comfort is at the core of the care provided in hospice.

The title suggests the keyword ‘peaceful death’ to convey that aspiration.

But why a "peaceful" death, rather than a "comfortable" death? When hospice staff say the patient is "comfortable," they are "expressing a general feeling that 'the patient is in a difficult but manageable state of daily life,' rather than 'the absence of pain'" (p. 273).

Furthermore, patient comfort “does not only refer to physical comfort,” but can also be seen as “the expansion of the patient’s mental space” (p. 284).

Rather than the keyword "comfortable death," which can easily be focused on the physical meaning when presented without any specific context, I tried to express the purpose of this book with the keyword "peaceful death," which focuses on the patient's inner self and the relationship between them without excluding realistic pain.

The contents of each chapter are as follows (the contents of each chapter are excerpted from the ‘Preface’).

Part 1 provides an overview of hospice through ‘space’ (Chapter 1) and ‘food’ (Chapter 2).

First, in Chapter 1, we will look at the garden, café, prayer room, patient rooms, bathroom, and program room of Dongbaek St. Luke's Hospital and examine the values that are central to the design and operation of the hospice space.

Chapter 2, 'Food', sharply reveals the characteristics of hospice care through eating, the most basic condition of life.

In hospice, you come to realize that food is not just for survival, but an existential and social thing that gives meaning to life.

Part 2 covers the medical care provided in hospice care in detail, under the topics of ‘Terminal Diagnosis’ (Chapter 3) and ‘Symptoms’ (Chapter 4).

In Korea, a complex mix of legal, institutional, social, and medical factors makes it by no means easy to declare a terminal illness to a cancer patient.

Chapter 3, “Terminal Diagnosis,” delves into this difficult reality in detail.

Chapter 4, “Symptoms,” then examines hospice’s approach to patient pain and the ethical challenges that arise from it.

It highlights how pain and suffering are dealt with, particularly in hospice.

Part 3 highlights the characteristics of hospice care using the keywords ‘care’ (Chapter 5) and ‘mourning’ (Chapter 6).

Chapter 5, “Care,” focuses on the meticulous care that is rarely seen in general hospitals and the working methods of the multidisciplinary team that makes this possible.

It clearly states that care is at the heart of hospice.

Finally, Chapter 6, ‘Mourning,’ conveys the scene in the death room when the patient is dying and the scenery after the death.

It shows the image of the holistic care that hospice aims for, from the physical symptoms of terminally ill patients to the work of multidisciplinary team members during that period and care for bereaved families.

The content written in this way was meticulously reviewed by 10 experts from various fields.

There were various opinions on the basic facts, logical structure, appropriateness of discourse, and content composition, and these were faithfully reflected in the final completion.

The list of 10 experts is as follows: Dongbaek St. Luke's Hospital Director Jeong Geuk-gyu, Department Head Lee Jeong-ae, Seoul National University Hematology and Oncology Professor Kim Beom-seok, Soonchunhyang University School of Medicine Professor Kim Hyeong-sook, Kyungpook National University School of Medicine Professor Choi Eun-kyung and Professor Kang Ji-yeon, Ewha Womans University Law School Professor Kim Hyeon-cheol, Sugiyama Jogakuen University Department of Information and Society Professor Kabumoto Chizuru, Seoul National University Department of Anthropology Professor Lee Hyeon-jeong, and EBS Documentary Prime reporter Kim Seo-yoon for 'Where is My Last Home?'

Seeking Alternatives to Death Today

“How to treat people as people

“It shows the answer.”

Choi Jin-young (novelist, author of "Proof of the Sphere")

Death is painful, but the process of dying is even more painful.

Because the process of dying in a hospital is not so easy.

It's not easy to sacrifice daily life for intensive treatment at a large hospital, but it's also not easy to endure the gloom that slowly eats away at one's life as one moves back and forth between nursing homes and convalescent hospitals.

Many people in Korean society are so aware of this fact that they are consumed by a desire to escape the pain, a “desire to die cleanly” (p. 9).

It is in this context that the so-called pro-euthanasia opinion appears to be around 80% in opinion polls.

But is this the only way to escape suffering? Shouldn't we explore alternatives before making a convenient, yet risky, choice? Could it be that we're obsessed with efficiency, even when it comes to death? While the two authors of this book fully agree that the face of death today needs to change, they believe we should seek a slower, more nuanced approach, rather than a hasty one.

A process of death that relieves the patient's suffering while also being considered complete by both the guardian and the hospital staff.

It is not too late to think about simple and so-called clean means later.

With this problem in mind, what the authors are focusing on is 'hospice'.

This book, focusing on hospice, provides a stark reflection on the reality of terminal care and death in Korean society today.

Hospice is commonly known as a place where terminally ill cancer patients spend the last days of their lives.

Medical anthropologist Song Byeong-gi and hospice doctor Kim Ho-seong go beyond this simple impression and meticulously examine, based on their respective expertise, what hospice does, how it operates, and its institutional and systematic characteristics.

It explores the topic of hospice and death through a multi-faceted lens, including vivid field experiences and episodes, institutional analysis, cross-cultural perspectives, historical review, and anthropological exploration.

The authors selected six keywords (space, food, terminal diagnosis, symptoms, care, and grief) and held several conversations over the course of two years. Based on the transcripts, they meticulously supplemented the book with new writing and numerous other materials.

By presenting it in a conversational format rather than narrative prose, the authors' mutual understanding is clearly revealed, while also facilitating easy understanding for readers.

It is particularly noteworthy that it is a hospice story that deals with the Korean situation and Korean questions.

This book presents hospice practices in a rich context as a response to “neither letting patients die nor leaving them to die” (p. 369), and explores alternatives to death that go beyond the treatment-centered paradigm.

“In the midst of the death scene that modern medicine has missed,

“I diligently gather pieces of hints for the future.”

Jang Il-ho (journalist, author of "A Visit from Sadness")

Why a 'peaceful death'?

The main goal of hospice is the physical, psychological, and social 'comfort' of the patient.

To make the patient's body and mind comfortable, we administer medication, provide nutrition, provide counseling, and implement various therapies.

The value of patient comfort is at the core of the care provided in hospice.

The title suggests the keyword ‘peaceful death’ to convey that aspiration.

But why a "peaceful" death, rather than a "comfortable" death? When hospice staff say the patient is "comfortable," they are "expressing a general feeling that 'the patient is in a difficult but manageable state of daily life,' rather than 'the absence of pain'" (p. 273).

Furthermore, patient comfort “does not only refer to physical comfort,” but can also be seen as “the expansion of the patient’s mental space” (p. 284).

Rather than the keyword "comfortable death," which can easily be focused on the physical meaning when presented without any specific context, I tried to express the purpose of this book with the keyword "peaceful death," which focuses on the patient's inner self and the relationship between them without excluding realistic pain.

The contents of each chapter are as follows (the contents of each chapter are excerpted from the ‘Preface’).

Part 1 provides an overview of hospice through ‘space’ (Chapter 1) and ‘food’ (Chapter 2).

First, in Chapter 1, we will look at the garden, café, prayer room, patient rooms, bathroom, and program room of Dongbaek St. Luke's Hospital and examine the values that are central to the design and operation of the hospice space.

Chapter 2, 'Food', sharply reveals the characteristics of hospice care through eating, the most basic condition of life.

In hospice, you come to realize that food is not just for survival, but an existential and social thing that gives meaning to life.

Part 2 covers the medical care provided in hospice care in detail, under the topics of ‘Terminal Diagnosis’ (Chapter 3) and ‘Symptoms’ (Chapter 4).

In Korea, a complex mix of legal, institutional, social, and medical factors makes it by no means easy to declare a terminal illness to a cancer patient.

Chapter 3, “Terminal Diagnosis,” delves into this difficult reality in detail.

Chapter 4, “Symptoms,” then examines hospice’s approach to patient pain and the ethical challenges that arise from it.

It highlights how pain and suffering are dealt with, particularly in hospice.

Part 3 highlights the characteristics of hospice care using the keywords ‘care’ (Chapter 5) and ‘mourning’ (Chapter 6).

Chapter 5, “Care,” focuses on the meticulous care that is rarely seen in general hospitals and the working methods of the multidisciplinary team that makes this possible.

It clearly states that care is at the heart of hospice.

Finally, Chapter 6, ‘Mourning,’ conveys the scene in the death room when the patient is dying and the scenery after the death.

It shows the image of the holistic care that hospice aims for, from the physical symptoms of terminally ill patients to the work of multidisciplinary team members during that period and care for bereaved families.

The content written in this way was meticulously reviewed by 10 experts from various fields.

There were various opinions on the basic facts, logical structure, appropriateness of discourse, and content composition, and these were faithfully reflected in the final completion.

The list of 10 experts is as follows: Dongbaek St. Luke's Hospital Director Jeong Geuk-gyu, Department Head Lee Jeong-ae, Seoul National University Hematology and Oncology Professor Kim Beom-seok, Soonchunhyang University School of Medicine Professor Kim Hyeong-sook, Kyungpook National University School of Medicine Professor Choi Eun-kyung and Professor Kang Ji-yeon, Ewha Womans University Law School Professor Kim Hyeon-cheol, Sugiyama Jogakuen University Department of Information and Society Professor Kabumoto Chizuru, Seoul National University Department of Anthropology Professor Lee Hyeon-jeong, and EBS Documentary Prime reporter Kim Seo-yoon for 'Where is My Last Home?'

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: December 1, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 408 pages | 604g | 140*210*23mm

- ISBN13: 9791189336776

- ISBN10: 1189336774

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)