There's a climate monster living inside me.

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

- Modern people are sick.

It may be due to excessive competition and complex social structures.

However, 『The Climate Monster Lives Inside Me』 presents a different perspective.

It is highly likely that climate change has caused problems for our physical and mental health.

Cognitive decline, increased anger, and epidemics of infectious diseases may not be just coincidences.

- Min-gyu Son, PD of Natural Sciences

For those who have long considered climate change a "natural problem," the examples presented in this book will be quite shocking.

"The evidence of climate change isn't heat waves, wildfires, typhoons, or droughts, but 'our own bodies'?" This book overturns the complacent mindset that has viewed climate disasters as near-future events or apocalyptic spectacles, exposing the reality of climate disasters currently unfolding within our very bodies.

Author Clayton Page Alden, a neuroscientist and environmental journalist, uses neuroscience, data science, and cognitive psychology to explain how climate change is causing devastating problems across our brains, bodies, and minds.

From memory loss, to the onset of violence, to the rise of neurodegenerative diseases, to the resurgence of infectious diseases, to the explosion of trauma and depression, the silent approach of the "climate monster" that controls humanity is revealed in detail.

"The evidence of climate change isn't heat waves, wildfires, typhoons, or droughts, but 'our own bodies'?" This book overturns the complacent mindset that has viewed climate disasters as near-future events or apocalyptic spectacles, exposing the reality of climate disasters currently unfolding within our very bodies.

Author Clayton Page Alden, a neuroscientist and environmental journalist, uses neuroscience, data science, and cognitive psychology to explain how climate change is causing devastating problems across our brains, bodies, and minds.

From memory loss, to the onset of violence, to the rise of neurodegenerative diseases, to the resurgence of infectious diseases, to the explosion of trauma and depression, the silent approach of the "climate monster" that controls humanity is revealed in detail.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommended Reading: Climate Change: The Monster Within Me

Prologue: Climate change exists both inside and outside of us.

Part 1: Dangerous Signals from the Brain

Chapter 1: Memory: When I Forget the Climate Within Me

Is the Climate Changing? | How Climate Became Part of Us | Rapidly Changing Climate Causes Amnesia | The Pitfalls of Updating Climate Normals for Future Forecasting | Shifting Baselines: Gradual Acclimation to Gradual Destruction | 'Climate Empathy': The Antidote to 'Climate Amnesia'

Chapter 2: Cognition: The Brain Is Embedded in Nature

Abnormal brain signals in hot places | Cognitive decline due to heat waves and air pollution | Objective judgment is an illusion in the face of soaring temperatures | The brain becomes dull to survive heat waves | Biological organisms sensitive to the environment | Ecoclimate design to restore climate damage

Chapter 3: Action: Who Killed Tyson Morlock?

How External Pressures Aggravate Stress | Rising Temperatures Fuel Retaliatory Actions | The Link Between Temperature, Serotonin, and Violence | Does Climate Change Even Determine Our Free Will? | How to Develop Self-Control in a World of Explosive Impulsivity

Part 2: How the Body Twists

Chapter 4 Neurodegeneration: The Bloom of Toxins

The Strange Brains of Bottlenose Dolphins and Vervet Monkeys | Amino Acid Toxins Spewed by Cyanobacteria | Neurotoxins Found Across the Marine Food Chain | Climate Change Fuels Cyanobacterial Booms | Dementia Spreads from Deserts to Coastlines | The Synergistic Effect of Mercury Poisoning, Paralysis, and Alzheimer's | Why the Risks of Cyanotoxins Are Unregulated | What Aerosol Detectors Find in Your Backyard

Chapter 5: Infection: The Great Revenge of Disease

When amoebas get up your nose in summer | Brain diseases on the rise with climate change | Underestimating disease means you can't control it | Rabies spread by vampire bats that have become climate refugees | Climate diseases don't come equally | Environmental stress experienced by individuals throughout their lives | Innovations in public health policy strengthen interconnectedness | How to respond to new infectious brain diseases

Chapter 6 Trauma: When the Whirlwind Rises Inside You

How Post-Traumatic Stress Responds to Our Bodies | Trauma is Both Innate and Acquired | When Environmental Trauma Becomes Physical Disability | Reconstructing Memory to Weaken Trauma | Neurological Antidotes to the Impacts of Climate Change | What Happens to the Brain and People When We Immerse Ourselves in a Story

Part 3: The Mind, a Movement of Loss and Recovery

Chapter 7: Senses: The Power that Connects the Brain and the World

Excessive carbon dioxide causes hearing loss in fish | Minimize surprise, maximize sensory evidence | The brain and the world dance and change together | A sense of losing sound and color due to climate change | The body's game of agile prediction, response, and action | The unpredictable movement that creates a livable planet

Chapter 8: Pain: A Call for Empathy

Extreme weather fuels climate anxiety | Solarstalgia, the depression caused by climate change | When a mountaintop disappears, a community disappears | Mental health worsens in underdeveloped areas | Suffering connects mind, body, and world | Traces of climate migrants who lost their homes | Resilience and adaptability to navigate rough waters

Chapter 9 Language: The Grammar of the Earth Left Behind by the Sami Language

GEASSI (summer) | ?AK?A-GEASSI (autumn-summer) | RAGAT (estrus) | VUOSTTA? MUOHTA (first snow) | SKABMA (dark period) | DALVI (winter) | DALVEGUOVDIL (midwinter) | GIđđA (spring) | GUOTTET (calving season)

Epilogue: Feeling the Weight of Nature Together

Acknowledgements

Notes and References

Prologue: Climate change exists both inside and outside of us.

Part 1: Dangerous Signals from the Brain

Chapter 1: Memory: When I Forget the Climate Within Me

Is the Climate Changing? | How Climate Became Part of Us | Rapidly Changing Climate Causes Amnesia | The Pitfalls of Updating Climate Normals for Future Forecasting | Shifting Baselines: Gradual Acclimation to Gradual Destruction | 'Climate Empathy': The Antidote to 'Climate Amnesia'

Chapter 2: Cognition: The Brain Is Embedded in Nature

Abnormal brain signals in hot places | Cognitive decline due to heat waves and air pollution | Objective judgment is an illusion in the face of soaring temperatures | The brain becomes dull to survive heat waves | Biological organisms sensitive to the environment | Ecoclimate design to restore climate damage

Chapter 3: Action: Who Killed Tyson Morlock?

How External Pressures Aggravate Stress | Rising Temperatures Fuel Retaliatory Actions | The Link Between Temperature, Serotonin, and Violence | Does Climate Change Even Determine Our Free Will? | How to Develop Self-Control in a World of Explosive Impulsivity

Part 2: How the Body Twists

Chapter 4 Neurodegeneration: The Bloom of Toxins

The Strange Brains of Bottlenose Dolphins and Vervet Monkeys | Amino Acid Toxins Spewed by Cyanobacteria | Neurotoxins Found Across the Marine Food Chain | Climate Change Fuels Cyanobacterial Booms | Dementia Spreads from Deserts to Coastlines | The Synergistic Effect of Mercury Poisoning, Paralysis, and Alzheimer's | Why the Risks of Cyanotoxins Are Unregulated | What Aerosol Detectors Find in Your Backyard

Chapter 5: Infection: The Great Revenge of Disease

When amoebas get up your nose in summer | Brain diseases on the rise with climate change | Underestimating disease means you can't control it | Rabies spread by vampire bats that have become climate refugees | Climate diseases don't come equally | Environmental stress experienced by individuals throughout their lives | Innovations in public health policy strengthen interconnectedness | How to respond to new infectious brain diseases

Chapter 6 Trauma: When the Whirlwind Rises Inside You

How Post-Traumatic Stress Responds to Our Bodies | Trauma is Both Innate and Acquired | When Environmental Trauma Becomes Physical Disability | Reconstructing Memory to Weaken Trauma | Neurological Antidotes to the Impacts of Climate Change | What Happens to the Brain and People When We Immerse Ourselves in a Story

Part 3: The Mind, a Movement of Loss and Recovery

Chapter 7: Senses: The Power that Connects the Brain and the World

Excessive carbon dioxide causes hearing loss in fish | Minimize surprise, maximize sensory evidence | The brain and the world dance and change together | A sense of losing sound and color due to climate change | The body's game of agile prediction, response, and action | The unpredictable movement that creates a livable planet

Chapter 8: Pain: A Call for Empathy

Extreme weather fuels climate anxiety | Solarstalgia, the depression caused by climate change | When a mountaintop disappears, a community disappears | Mental health worsens in underdeveloped areas | Suffering connects mind, body, and world | Traces of climate migrants who lost their homes | Resilience and adaptability to navigate rough waters

Chapter 9 Language: The Grammar of the Earth Left Behind by the Sami Language

GEASSI (summer) | ?AK?A-GEASSI (autumn-summer) | RAGAT (estrus) | VUOSTTA? MUOHTA (first snow) | SKABMA (dark period) | DALVI (winter) | DALVEGUOVDIL (midwinter) | GIđđA (spring) | GUOTTET (calving season)

Epilogue: Feeling the Weight of Nature Together

Acknowledgements

Notes and References

Detailed image

Into the book

By summarizing the contents of this book, we will be able to recognize one truth about climate change that we, as scholars, politicians, and individuals, have ignored without even realizing that it is eating away at our own lives.

Despite the serious public health crisis that climate change poses on our brains, little has been reported on it.

In fact, it is already too late to take action.

Immigration officers are more likely to reject asylum applications on hotter days.

Some medications that act on the brain become less effective as temperatures rise.

Frequent forest fires take away people's homes.

Chronic stress has become a disease.

As the climate changes, so do ecosystems, allowing previously unheard-of disease vectors, from malaria-carrying mosquitoes to brain-eating amoebas, to expand their reach.

As natural landscapes are lost, rates of severe depression also soar.

Students taking tests on hot days are more likely to get a few questions wrong.

In this way, we are suffering from the climate crisis, knowingly or unknowingly.

It's a terrifying reality.

No, it is a reality that must feel terrifying.

--- From the "Prologue"

According to Frankland, the rate at which forgetting occurs depends in part on how predictable the environment is.

“In dynamic environments, the usefulness of existing information decreases over time, whereas in static environments, the usefulness of existing information is maintained, so forgetting may occur less frequently.” If the purpose of performing active forgetting is to accurately model the world, then when the environment changes, there also arises a need to adjust certain beliefs that conflict with reality.

In other words, the brain tries to suppress inaccurate knowledge.

Frankland also points out this:

“Not all memories fade equally.”

--- From "Chapter 1: Memory: When I Forget the Climate Within Me"

A team of researchers at the University of Ottawa, led by economist Anthony Hayes, wanted to test how the asylum process would behave under stress.

Could this kind of judgment—a judgment "largely unrelated to the temperature at the time"—be influenced by seemingly unrelated factors? Like any outstanding economist, Hayes collected hundreds of thousands of relevant cases.

After collecting four years' worth of 200,000 decisions and isolating the impact of temperature, they found that for every 10 degrees Fahrenheit increase in outdoor temperatures, the likelihood of an asylum officer making a favorable decision fell by nearly 7 percent.

The researchers added.

“In other words, if we look at this sample from a lenient perspective, the difference in approval probability between the top 25% of judges and the bottom 25% is 7.9%.” Objectivity was an illusion in the face of temperature.

--- From "Chapter 2 Cognition: The Brain is Embedded in Nature"

Narayan wanted to understand which aspects of the workplace and its surrounding socioeconomic context influenced instances of discrimination and harassment.

In other words, we wanted to measure the impact of each work environment and each employee's background on the likelihood of committing discriminatory acts.

After months of analyzing 250,000 EEO (equal employment opportunity) data sets using a variety of statistical techniques, Narayan published his rigorous and precise findings in the 2022 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Among the factors that influence discrimination, temperature was also one of them.

Assuming all other things are equal, EEO complaints increased by 5% on days with a high temperature above 32 degrees Celsius compared to days with a high temperature between 16 and 21 degrees Celsius.

As temperatures rose, the number of union complaints also increased by nearly 4 percent.

Also, as with Anthony Hayes's investigation of immigration officers, the effects of heat were found to persist indoors.

Because whether they were postmen or office workers, they were equally affected.

--- From "Chapter 3 Action: Who Killed Tyson Morlock"

A shocking pattern of mass outbreaks has been revealed.

Nine of the cases were recorded near Lake Mascoma in western New Hampshire, where a summer blue-green algae bloom occurred.

Worldwide, only about 2 to 3 people per million are diagnosed with ALS (Lou Gehrig's disease) each year.

So, nine people getting sick near the lake represents an outbreak rate that is 10 to 25 times higher than average.

The patients were not related, so the cause was not genetic.

Moreover, outbreaks were mostly concentrated along the coast, which is affected by prevailing winds.

Even among the patients were the landlord and the gardener, and it was revealed that the two often visited the same place.

Stomel emphasizes this:

“That doesn’t mean that cyanobacteria cause ALS cases.

However, it does mean that being near murky water puts you at risk for developing ALS.”

--- From "Chapter 4 Neurodegeneration: The Bloom of Toxic Substances"

The theory that vampire bats are causing rabies due to climate change goes like this.

Vampire bats are creatures that play a complex ecological role.

It means that our very existence is intertwined with the delicate balance of the ecosystem.

But as climate change takes hold, vampire bats face a double threat.

Because the changeable weather and rising temperatures affect not only habitats but also food.

Even vampire bats are ultimately climate refugees.

As the animals are forced out of their original habitat, the rabies virus moves with them.

--- From "Chapter 5 Infection: The Great Revenge of Disease"

As we have seen, PTSD often causes temporal dislocation.

Past trauma seeps into the present, overwhelming our sense of security and control.

But meditation helps us navigate the darkness by grounding us firmly in the continuous flow of sensory experience.

The forest of the mind can be a place filled with danger and uncertainty, but it is also a place of wonder, beauty, resilience, and adaptability.

Through meditation, we can see trauma as part of the landscape, rather than as a disaster that fills the landscape.

By caring for your own wounds with compassion and enduring your inner storms with grace, you can regain your capacity for growth and adaptability.

You can make peace with the trauma you've experienced and integrate it into the larger narrative of your life.

--- From "Chapter 6 Trauma: When the Whirlwind Rises Inside Your Body"

The magic of surprise minimization theory is that it provides tools to read the dynamics of nature in the same language at all scales of analysis.

We can use the same language for mitochondria, cells, organisms, species, and ecosystems.

If that sounds too arbitrary, it's because you're not yet used to thinking that way.

It's hard to believe that the same mechanisms for sustainable existence apply to a single brain cell, an individual bonobo, or an entire forest colony of apricot mushrooms.

Priston's research doesn't simply dismantle boundaries and claim, "We're all connected."

Rather, the surprise minimization theory is intended to limit individual existence.

To make sense, individuality is ultimately necessary.

Of course we are all connected.

But it's boring.

What's not boring is that, despite the boundaries that intricately separate us and the interconnectedness between objects and their environments, we share a definition of success with everything else that physically exists.

“Sustainability” means the same thing to everyone.

--- From "Chapter 7 Senses: The Power that Connects the Brain and the World"

Pain reminds us that our brain exists in our body and that our body exists in space.

We have to eat.

We must exercise.

We should treat our bodies like bodies.

Think about how your hand flinches when it touches fire.

The movement itself is not a separate response to a painful stimulus.

It is a movement of self-preservation.

It is a story realized through danger and escape.

Hands not only convey the sensation of pain, but also express it through action.

A specific story of suffering is recorded in that movement.

Our painful experiences are also deeply intertwined with our emotions, thoughts, and memories.

Painful experiences can trigger painful memories from the past, trigger feelings of fear or stress, and trigger thoughts of harm or threat.

Pain is a complex intertwining of sensations, emotions, cognitions, and memories.

When we embody awareness by remembering our bodies as bodies, suffering reveals itself as a complex part of our being, demonstrating the deep interconnectedness of mind, body, self, and world.

--- From "Chapter 8 Pain: A Call for Empathy"

The words we use, the dialects we choose, and the stories we tell change and move with us as we navigate the winding paths of life.

Personal and collective experiences are etched into the language we use, which in turn shapes the linguistic environment for future generations.

Northern Sami may have a word for snow that a Hawaiian might never know, and Hawaiian may have a word to describe a subtle aspect of the ocean that would forever be foreign to a Northern Sami speaker.

Our language is both a map and a mirror.

Despite the serious public health crisis that climate change poses on our brains, little has been reported on it.

In fact, it is already too late to take action.

Immigration officers are more likely to reject asylum applications on hotter days.

Some medications that act on the brain become less effective as temperatures rise.

Frequent forest fires take away people's homes.

Chronic stress has become a disease.

As the climate changes, so do ecosystems, allowing previously unheard-of disease vectors, from malaria-carrying mosquitoes to brain-eating amoebas, to expand their reach.

As natural landscapes are lost, rates of severe depression also soar.

Students taking tests on hot days are more likely to get a few questions wrong.

In this way, we are suffering from the climate crisis, knowingly or unknowingly.

It's a terrifying reality.

No, it is a reality that must feel terrifying.

--- From the "Prologue"

According to Frankland, the rate at which forgetting occurs depends in part on how predictable the environment is.

“In dynamic environments, the usefulness of existing information decreases over time, whereas in static environments, the usefulness of existing information is maintained, so forgetting may occur less frequently.” If the purpose of performing active forgetting is to accurately model the world, then when the environment changes, there also arises a need to adjust certain beliefs that conflict with reality.

In other words, the brain tries to suppress inaccurate knowledge.

Frankland also points out this:

“Not all memories fade equally.”

--- From "Chapter 1: Memory: When I Forget the Climate Within Me"

A team of researchers at the University of Ottawa, led by economist Anthony Hayes, wanted to test how the asylum process would behave under stress.

Could this kind of judgment—a judgment "largely unrelated to the temperature at the time"—be influenced by seemingly unrelated factors? Like any outstanding economist, Hayes collected hundreds of thousands of relevant cases.

After collecting four years' worth of 200,000 decisions and isolating the impact of temperature, they found that for every 10 degrees Fahrenheit increase in outdoor temperatures, the likelihood of an asylum officer making a favorable decision fell by nearly 7 percent.

The researchers added.

“In other words, if we look at this sample from a lenient perspective, the difference in approval probability between the top 25% of judges and the bottom 25% is 7.9%.” Objectivity was an illusion in the face of temperature.

--- From "Chapter 2 Cognition: The Brain is Embedded in Nature"

Narayan wanted to understand which aspects of the workplace and its surrounding socioeconomic context influenced instances of discrimination and harassment.

In other words, we wanted to measure the impact of each work environment and each employee's background on the likelihood of committing discriminatory acts.

After months of analyzing 250,000 EEO (equal employment opportunity) data sets using a variety of statistical techniques, Narayan published his rigorous and precise findings in the 2022 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Among the factors that influence discrimination, temperature was also one of them.

Assuming all other things are equal, EEO complaints increased by 5% on days with a high temperature above 32 degrees Celsius compared to days with a high temperature between 16 and 21 degrees Celsius.

As temperatures rose, the number of union complaints also increased by nearly 4 percent.

Also, as with Anthony Hayes's investigation of immigration officers, the effects of heat were found to persist indoors.

Because whether they were postmen or office workers, they were equally affected.

--- From "Chapter 3 Action: Who Killed Tyson Morlock"

A shocking pattern of mass outbreaks has been revealed.

Nine of the cases were recorded near Lake Mascoma in western New Hampshire, where a summer blue-green algae bloom occurred.

Worldwide, only about 2 to 3 people per million are diagnosed with ALS (Lou Gehrig's disease) each year.

So, nine people getting sick near the lake represents an outbreak rate that is 10 to 25 times higher than average.

The patients were not related, so the cause was not genetic.

Moreover, outbreaks were mostly concentrated along the coast, which is affected by prevailing winds.

Even among the patients were the landlord and the gardener, and it was revealed that the two often visited the same place.

Stomel emphasizes this:

“That doesn’t mean that cyanobacteria cause ALS cases.

However, it does mean that being near murky water puts you at risk for developing ALS.”

--- From "Chapter 4 Neurodegeneration: The Bloom of Toxic Substances"

The theory that vampire bats are causing rabies due to climate change goes like this.

Vampire bats are creatures that play a complex ecological role.

It means that our very existence is intertwined with the delicate balance of the ecosystem.

But as climate change takes hold, vampire bats face a double threat.

Because the changeable weather and rising temperatures affect not only habitats but also food.

Even vampire bats are ultimately climate refugees.

As the animals are forced out of their original habitat, the rabies virus moves with them.

--- From "Chapter 5 Infection: The Great Revenge of Disease"

As we have seen, PTSD often causes temporal dislocation.

Past trauma seeps into the present, overwhelming our sense of security and control.

But meditation helps us navigate the darkness by grounding us firmly in the continuous flow of sensory experience.

The forest of the mind can be a place filled with danger and uncertainty, but it is also a place of wonder, beauty, resilience, and adaptability.

Through meditation, we can see trauma as part of the landscape, rather than as a disaster that fills the landscape.

By caring for your own wounds with compassion and enduring your inner storms with grace, you can regain your capacity for growth and adaptability.

You can make peace with the trauma you've experienced and integrate it into the larger narrative of your life.

--- From "Chapter 6 Trauma: When the Whirlwind Rises Inside Your Body"

The magic of surprise minimization theory is that it provides tools to read the dynamics of nature in the same language at all scales of analysis.

We can use the same language for mitochondria, cells, organisms, species, and ecosystems.

If that sounds too arbitrary, it's because you're not yet used to thinking that way.

It's hard to believe that the same mechanisms for sustainable existence apply to a single brain cell, an individual bonobo, or an entire forest colony of apricot mushrooms.

Priston's research doesn't simply dismantle boundaries and claim, "We're all connected."

Rather, the surprise minimization theory is intended to limit individual existence.

To make sense, individuality is ultimately necessary.

Of course we are all connected.

But it's boring.

What's not boring is that, despite the boundaries that intricately separate us and the interconnectedness between objects and their environments, we share a definition of success with everything else that physically exists.

“Sustainability” means the same thing to everyone.

--- From "Chapter 7 Senses: The Power that Connects the Brain and the World"

Pain reminds us that our brain exists in our body and that our body exists in space.

We have to eat.

We must exercise.

We should treat our bodies like bodies.

Think about how your hand flinches when it touches fire.

The movement itself is not a separate response to a painful stimulus.

It is a movement of self-preservation.

It is a story realized through danger and escape.

Hands not only convey the sensation of pain, but also express it through action.

A specific story of suffering is recorded in that movement.

Our painful experiences are also deeply intertwined with our emotions, thoughts, and memories.

Painful experiences can trigger painful memories from the past, trigger feelings of fear or stress, and trigger thoughts of harm or threat.

Pain is a complex intertwining of sensations, emotions, cognitions, and memories.

When we embody awareness by remembering our bodies as bodies, suffering reveals itself as a complex part of our being, demonstrating the deep interconnectedness of mind, body, self, and world.

--- From "Chapter 8 Pain: A Call for Empathy"

The words we use, the dialects we choose, and the stories we tell change and move with us as we navigate the winding paths of life.

Personal and collective experiences are etched into the language we use, which in turn shapes the linguistic environment for future generations.

Northern Sami may have a word for snow that a Hawaiian might never know, and Hawaiian may have a word to describe a subtle aspect of the ocean that would forever be foreign to a Northern Sami speaker.

Our language is both a map and a mirror.

--- From "Chapter 9 Language: The Grammar of the Earth Left Behind by the Sami Language"

Publisher's Review

“As the spectacle ended, the silent assault began.”

An invisible disaster that permeates every nook and cranny of the body.

A defining moment when climate change changes our thoughts, feelings, and actions.

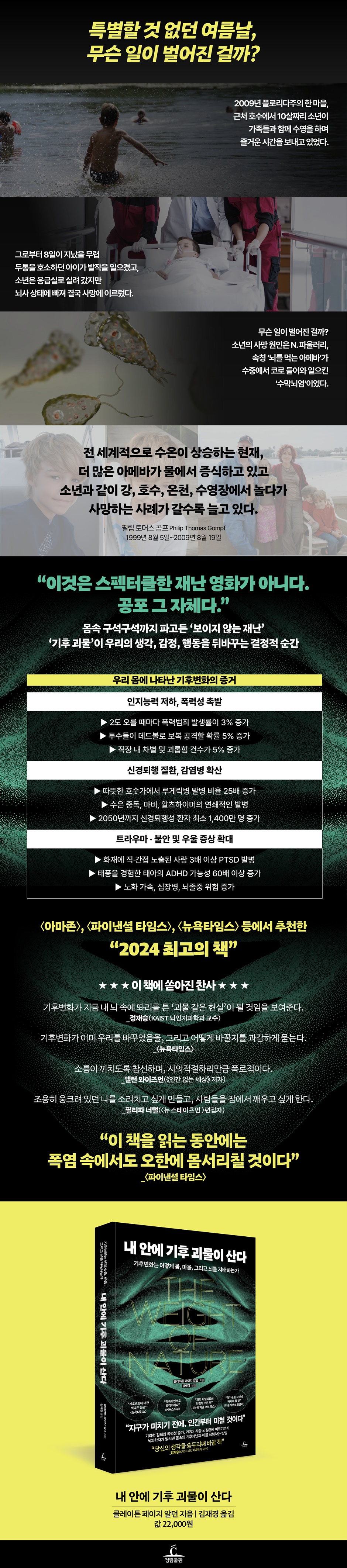

An unremarkable summer day,

What happened?

It was a perfectly ordinary summer day in Auburndale, Florida, in 2009.

On this day, a 10-year-old boy was having a good time swimming with his relatives in a nearby lake.

About five or six days later, the boy complained of a headache to his mother and father, who were infectious disease specialists.

There was no fever and the child had no stiff neck, so the couple reassured the child and put him to sleep.

The next morning, the boy could not wake up, his body completely frozen.

His father rushed him to the emergency room, but his condition did not improve and the boy began to have seizures.

And then he fell into a brain dead state.

It had been eight days since I had swum in the lake.

The couple, who had been watching their child in a vegetative state and unable to be revived, eventually had to make the difficult decision to remove the life support machine.

What happened? The boy's cause of death was N.

It was meningoencephalitis caused by Fowleri's disease, commonly known as the 'brain-eating amoeba', entering the nose from underwater.

Although only a small number of cases of N. fowleri infection are known, with water temperatures rising worldwide, more N. fowleri are becoming more common.

Fowleri is waking up, and there are more and more deaths from swimming in lakes, rivers, hot springs and pools while unprotected, like the boy.

In 2014, five years after the boy's death, his parents began actively raising awareness about the dangers of climate change with a campaign titled "Beware of the Summer of Amoeba Explosion."

?

“This isn’t a disaster movie, it’s horror itself.”

The true nature of the "climate monster" that silently attacks our bodies.

The above examples are just a small sample of the numerous data in this book.

For those who have long thought of climate change as a "natural problem," the examples presented in "The Weight of Nature" will be quite a shock.

"The evidence of climate change isn't heat waves, wildfires, typhoons, or droughts, but 'our own bodies'?" This book overturns the complacent mindset that has viewed climate disasters as near-future events or apocalyptic spectacles, exposing the reality of climate disasters currently unfolding within our very bodies.

Author Clayton Page Alden, a neuroscientist and environmental journalist, uses neuroscience, data science, and cognitive psychology to explain how climate change is causing devastating problems across our brains, bodies, and minds.

From memory loss, to the onset of violence, to the rise of neurodegenerative diseases, to the resurgence of infectious diseases, to the explosion of trauma and depression, the silent approach of the "climate monster" that controls humanity is revealed in detail.

Objectivity is an illusion in the face of soaring temperatures.

Changes in memory, cognition, and behavior caused by a damaged brain

Every year, we hear news of "record-breaking heat waves," and even though the ever-changing weather is becoming increasingly difficult to predict, we often try to ignore or turn a blind eye to the reality of climate change.

And this 'climate forgetting' is a phenomenon that can be explained neuroscientifically.

As the environment changes rapidly and predictability decreases, the rate at which the brain forgets also increases.

As if suffering from collective amnesia, the human attitude of forgetting the past and adapting to the present by continuously renewing the average temperature limit (climate normal) is creating a vicious cycle between the Earth and humans, and even within neural circuits.

From 'memory loss' to 'cognitive decline' and 'increased violence', Part 1 explores the various abnormal symptoms that climate change will cause in our cognitive behavior.

Experiments, data, and interviews clearly show that rising temperatures not only impair our judgment and work abilities, but also our school grades.

In the heat wave, the brain becomes dull and overheats as it heats up its metabolism to survive, and as a result, it reacts sensitively to even small stresses, which can even lead to death.

As serotonin, which regulates violent behavior in the brain, decreases, impulsivity increases and retaliatory behavior increases.

To break this vicious cycle, the author offers hints on 'climate empathy', 'history', and 'self-control' to control one's impulses and recognize one's future self.

“If you underestimate a disease, you can’t control it.”

How Twisted Bodies Lead to Neurodegeneration, Infection, and Trauma

Why did 800 bottlenose dolphins die en masse off the coast of Florida? Cyanobacteria, a blue-green algae that has affected all life throughout Earth's history, is exploding today, fueled by climate change. The amino acids they release are deadly neurotoxins, causing neurological disorders such as tremors, paralysis, and dementia.

Similar to the brains of vervet monkeys with Alzheimer's disease, the brains of bottlenose dolphins were honeycombed, and similar substances were found in the brains of people in Florida.

Anyone living in areas close to cyanobacteria, which proliferate in deserts and waterways, could not be free from diseases such as Lou Gehrig's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and mercury poisoning.

Part 2 details the "infectious diseases" and "trauma" that climate change will cause to our bodies, in addition to the horrific "neurodegenerative diseases."

In addition to the previously introduced 'meningoencephalitis', it reveals how dangerous Ebola hemorrhagic fever, yellow fever, and microcephaly are as zoonotic infectious diseases that are expected to increase in number. It also introduces PTSD symptoms suffered by people who have directly or indirectly experienced climate disasters and seeks solutions to treat them.

The author suggests that while innovation in public health policy can create a system that can respond quickly to diseases, for individuals, meditation (mindfulness) and storytelling can serve as ways to heal trauma.

“When one mountaintop disappears, the community disappears.”

A Journey of Loss and Recovery with Sense, Pain, and Language

What if the bloody clouds depicted in Munch's "The Scream" are the aftermath of the massive eruption of Krakatau, which occurred around the time the painting was created? "The Scream" isn't simply a depiction of the closed-off inner world of a person suffering from panic disorder.

And our psychology does not only mean an inner world that is completely separated from the outside world.

We interact with the world in ways that minimize surprise and maximize sensory evidence.

Ultimately, we either isolate ourselves (depression) as a rational way to cope with an overwhelmingly changing world, or we actively interact with the world, reacting and acting in a close manner.

The former will be a journey of 'loss' that our hearts will experience along with climate change, and the latter will be a journey of 'recovery'.

Part 3 introduces the 'theory of sensation and action' as well as the 'pain' and 'language loss' that climate change has caused in our minds.

It introduces not only 'climate anxiety', which refers to a pathological worry about the impending climate crisis, but also 'solastalgia' (nostalgia and depression caused by climate change) experienced by communities that have lost their mountains to open-pit mining, and talks about 'resilience' and 'adaptability' as the brain's neuroplasticity to overcome all of this reality, along with the wounds of climate migrants who have lost their homes.

Furthermore, he suggests that recalling the disappearing Sami language to delicately feel and understand the changing seasons and restoring the identity and linguistic diversity of ethnic minorities can be another way to respond to climate change.

“How to feel the ‘weight of nature’ with your whole body”

A delicate and thoughtful essay by a scientist who believes in the power of empathy.

Rather than the vague conclusions of existing environmental books calling for societal change, the author explores a variety of practical solutions from a deeply personal perspective.

What makes this book more than a simple data report and more than a flowing "science essay" is that the author's sharp argument shifts to a thoughtful style that offers unexpected comfort toward the end of each chapter.

The author reveals the gravity of "The Weight of Nature" as a massive impact of climate change, while also guiding us into the realm of "empathy," where we can feel, shoulder, and experience that weight together.

The author's meticulous approach, which examines underdeveloped communities already suffering irreversible damage from climate change, encourages us to reflect on ourselves and our surroundings "now," rather than making grand predictions about the future or making hasty alternatives.

Although we may not be able to change much immediately, the solutions presented in this book—meditation, storytelling, history, resilience, adaptability, and linguistic diversity—could be the "healing" we most need as we live with the reality of climate change.

An invisible disaster that permeates every nook and cranny of the body.

A defining moment when climate change changes our thoughts, feelings, and actions.

An unremarkable summer day,

What happened?

It was a perfectly ordinary summer day in Auburndale, Florida, in 2009.

On this day, a 10-year-old boy was having a good time swimming with his relatives in a nearby lake.

About five or six days later, the boy complained of a headache to his mother and father, who were infectious disease specialists.

There was no fever and the child had no stiff neck, so the couple reassured the child and put him to sleep.

The next morning, the boy could not wake up, his body completely frozen.

His father rushed him to the emergency room, but his condition did not improve and the boy began to have seizures.

And then he fell into a brain dead state.

It had been eight days since I had swum in the lake.

The couple, who had been watching their child in a vegetative state and unable to be revived, eventually had to make the difficult decision to remove the life support machine.

What happened? The boy's cause of death was N.

It was meningoencephalitis caused by Fowleri's disease, commonly known as the 'brain-eating amoeba', entering the nose from underwater.

Although only a small number of cases of N. fowleri infection are known, with water temperatures rising worldwide, more N. fowleri are becoming more common.

Fowleri is waking up, and there are more and more deaths from swimming in lakes, rivers, hot springs and pools while unprotected, like the boy.

In 2014, five years after the boy's death, his parents began actively raising awareness about the dangers of climate change with a campaign titled "Beware of the Summer of Amoeba Explosion."

?

“This isn’t a disaster movie, it’s horror itself.”

The true nature of the "climate monster" that silently attacks our bodies.

The above examples are just a small sample of the numerous data in this book.

For those who have long thought of climate change as a "natural problem," the examples presented in "The Weight of Nature" will be quite a shock.

"The evidence of climate change isn't heat waves, wildfires, typhoons, or droughts, but 'our own bodies'?" This book overturns the complacent mindset that has viewed climate disasters as near-future events or apocalyptic spectacles, exposing the reality of climate disasters currently unfolding within our very bodies.

Author Clayton Page Alden, a neuroscientist and environmental journalist, uses neuroscience, data science, and cognitive psychology to explain how climate change is causing devastating problems across our brains, bodies, and minds.

From memory loss, to the onset of violence, to the rise of neurodegenerative diseases, to the resurgence of infectious diseases, to the explosion of trauma and depression, the silent approach of the "climate monster" that controls humanity is revealed in detail.

Objectivity is an illusion in the face of soaring temperatures.

Changes in memory, cognition, and behavior caused by a damaged brain

Every year, we hear news of "record-breaking heat waves," and even though the ever-changing weather is becoming increasingly difficult to predict, we often try to ignore or turn a blind eye to the reality of climate change.

And this 'climate forgetting' is a phenomenon that can be explained neuroscientifically.

As the environment changes rapidly and predictability decreases, the rate at which the brain forgets also increases.

As if suffering from collective amnesia, the human attitude of forgetting the past and adapting to the present by continuously renewing the average temperature limit (climate normal) is creating a vicious cycle between the Earth and humans, and even within neural circuits.

From 'memory loss' to 'cognitive decline' and 'increased violence', Part 1 explores the various abnormal symptoms that climate change will cause in our cognitive behavior.

Experiments, data, and interviews clearly show that rising temperatures not only impair our judgment and work abilities, but also our school grades.

In the heat wave, the brain becomes dull and overheats as it heats up its metabolism to survive, and as a result, it reacts sensitively to even small stresses, which can even lead to death.

As serotonin, which regulates violent behavior in the brain, decreases, impulsivity increases and retaliatory behavior increases.

To break this vicious cycle, the author offers hints on 'climate empathy', 'history', and 'self-control' to control one's impulses and recognize one's future self.

“If you underestimate a disease, you can’t control it.”

How Twisted Bodies Lead to Neurodegeneration, Infection, and Trauma

Why did 800 bottlenose dolphins die en masse off the coast of Florida? Cyanobacteria, a blue-green algae that has affected all life throughout Earth's history, is exploding today, fueled by climate change. The amino acids they release are deadly neurotoxins, causing neurological disorders such as tremors, paralysis, and dementia.

Similar to the brains of vervet monkeys with Alzheimer's disease, the brains of bottlenose dolphins were honeycombed, and similar substances were found in the brains of people in Florida.

Anyone living in areas close to cyanobacteria, which proliferate in deserts and waterways, could not be free from diseases such as Lou Gehrig's disease, Alzheimer's disease, and mercury poisoning.

Part 2 details the "infectious diseases" and "trauma" that climate change will cause to our bodies, in addition to the horrific "neurodegenerative diseases."

In addition to the previously introduced 'meningoencephalitis', it reveals how dangerous Ebola hemorrhagic fever, yellow fever, and microcephaly are as zoonotic infectious diseases that are expected to increase in number. It also introduces PTSD symptoms suffered by people who have directly or indirectly experienced climate disasters and seeks solutions to treat them.

The author suggests that while innovation in public health policy can create a system that can respond quickly to diseases, for individuals, meditation (mindfulness) and storytelling can serve as ways to heal trauma.

“When one mountaintop disappears, the community disappears.”

A Journey of Loss and Recovery with Sense, Pain, and Language

What if the bloody clouds depicted in Munch's "The Scream" are the aftermath of the massive eruption of Krakatau, which occurred around the time the painting was created? "The Scream" isn't simply a depiction of the closed-off inner world of a person suffering from panic disorder.

And our psychology does not only mean an inner world that is completely separated from the outside world.

We interact with the world in ways that minimize surprise and maximize sensory evidence.

Ultimately, we either isolate ourselves (depression) as a rational way to cope with an overwhelmingly changing world, or we actively interact with the world, reacting and acting in a close manner.

The former will be a journey of 'loss' that our hearts will experience along with climate change, and the latter will be a journey of 'recovery'.

Part 3 introduces the 'theory of sensation and action' as well as the 'pain' and 'language loss' that climate change has caused in our minds.

It introduces not only 'climate anxiety', which refers to a pathological worry about the impending climate crisis, but also 'solastalgia' (nostalgia and depression caused by climate change) experienced by communities that have lost their mountains to open-pit mining, and talks about 'resilience' and 'adaptability' as the brain's neuroplasticity to overcome all of this reality, along with the wounds of climate migrants who have lost their homes.

Furthermore, he suggests that recalling the disappearing Sami language to delicately feel and understand the changing seasons and restoring the identity and linguistic diversity of ethnic minorities can be another way to respond to climate change.

“How to feel the ‘weight of nature’ with your whole body”

A delicate and thoughtful essay by a scientist who believes in the power of empathy.

Rather than the vague conclusions of existing environmental books calling for societal change, the author explores a variety of practical solutions from a deeply personal perspective.

What makes this book more than a simple data report and more than a flowing "science essay" is that the author's sharp argument shifts to a thoughtful style that offers unexpected comfort toward the end of each chapter.

The author reveals the gravity of "The Weight of Nature" as a massive impact of climate change, while also guiding us into the realm of "empathy," where we can feel, shoulder, and experience that weight together.

The author's meticulous approach, which examines underdeveloped communities already suffering irreversible damage from climate change, encourages us to reflect on ourselves and our surroundings "now," rather than making grand predictions about the future or making hasty alternatives.

Although we may not be able to change much immediately, the solutions presented in this book—meditation, storytelling, history, resilience, adaptability, and linguistic diversity—could be the "healing" we most need as we live with the reality of climate change.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 20, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 384 pages | 680g | 152*224*26mm

- ISBN13: 9791155402412

- ISBN10: 1155402413

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)