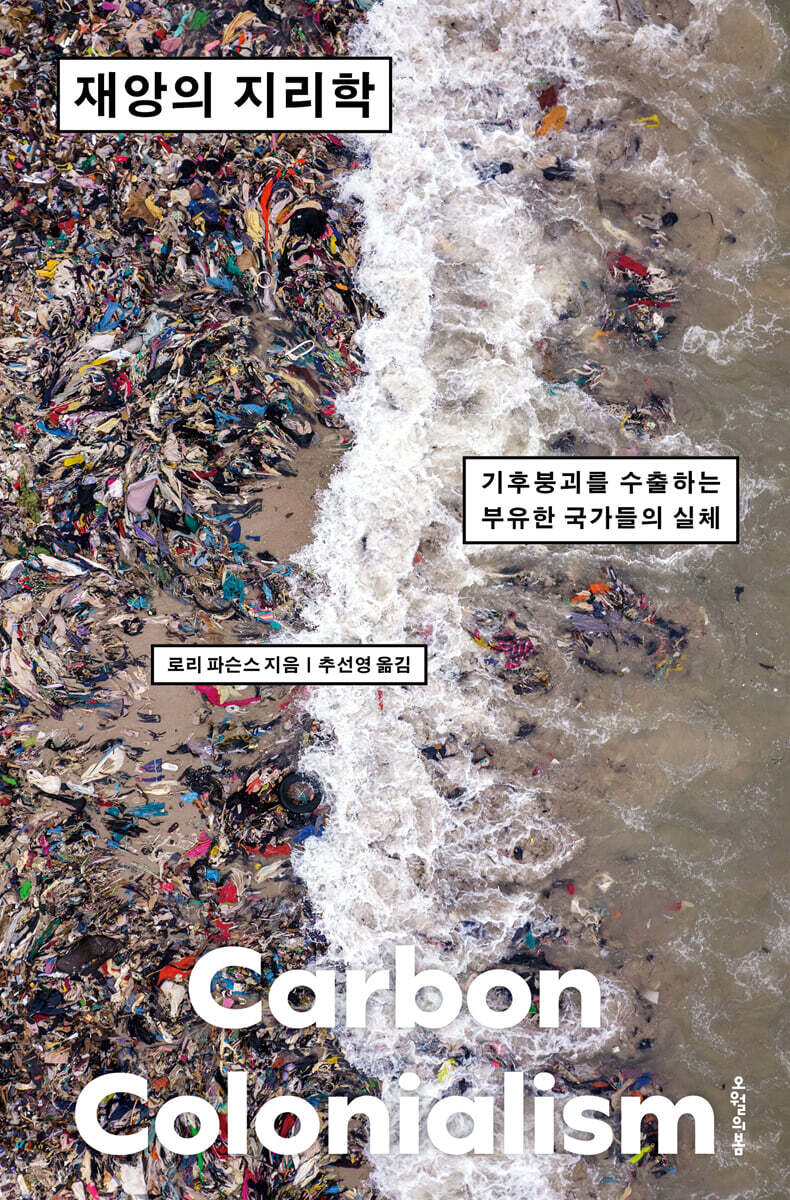

Geography of Disaster

|

Description

Book Introduction

On the massive inequality of the climate crisis

Behind ‘sustainability’ and ‘eco-friendliness’

The ugly faces of hypocrisy that sell disaster

“The climate never acts alone.

“Climate meets humans wearing the clothes of society.”

Can so-called "ethical consumption" practices like zero waste and reducing plastic use prevent the climate crisis? If so, why is the climate catastrophe worsening and accelerating? Global companies are churning out products with slogans and labels like "sustainability," "green growth," "fair trade," "eco-friendly," and "organic," and consumers' calls for "ethical production" are louder than ever.

But the reality is actually going in the opposite direction.

Geographer Laurie Parsons, who consistently writes from a labor perspective, casts strong doubts on such a "green outlook" and uncovers the truth hidden by global supply chains.

In an era of global production, where goods are no longer produced in a single country, how meaningless is it to advocate for "carbon reduction" solely based on domestic carbon emissions? Corporations relocate factories to poorer countries, selling off environmental pollution and climate collapse, while wealthy nations tolerate the ills of such overseas production and continue to only count carbon emissions within their own borders.

This is the reality of their eco-friendly and carbon-reduction efforts.

The author has been conducting field research at several production plants in Southeast Asia (Cambodia) to trace this outdated carbon accounting mechanism.

The starting point of the discussion is to face the fact that environmental degradation and the climate crisis are not neutral natural phenomena, but rather 'massive inequalities.'

Impressively, the author presents the climate crisis, which has been conveyed only through numbers, statistics, and shocking spectacle, through the life of an individual experiencing the phenomenon.

This 'subjectivity' aligns with the book's unique perspective: its brilliant way of problematizing climate change as a disaster that directly impacts the lives of the poor, not the rich.

As the author emphasizes, the climate never acts alone.

The climate reveals itself (only) through the lives of workers in brick kilns and garment subcontractors and the urban poor.

Behind ‘sustainability’ and ‘eco-friendliness’

The ugly faces of hypocrisy that sell disaster

“The climate never acts alone.

“Climate meets humans wearing the clothes of society.”

Can so-called "ethical consumption" practices like zero waste and reducing plastic use prevent the climate crisis? If so, why is the climate catastrophe worsening and accelerating? Global companies are churning out products with slogans and labels like "sustainability," "green growth," "fair trade," "eco-friendly," and "organic," and consumers' calls for "ethical production" are louder than ever.

But the reality is actually going in the opposite direction.

Geographer Laurie Parsons, who consistently writes from a labor perspective, casts strong doubts on such a "green outlook" and uncovers the truth hidden by global supply chains.

In an era of global production, where goods are no longer produced in a single country, how meaningless is it to advocate for "carbon reduction" solely based on domestic carbon emissions? Corporations relocate factories to poorer countries, selling off environmental pollution and climate collapse, while wealthy nations tolerate the ills of such overseas production and continue to only count carbon emissions within their own borders.

This is the reality of their eco-friendly and carbon-reduction efforts.

The author has been conducting field research at several production plants in Southeast Asia (Cambodia) to trace this outdated carbon accounting mechanism.

The starting point of the discussion is to face the fact that environmental degradation and the climate crisis are not neutral natural phenomena, but rather 'massive inequalities.'

Impressively, the author presents the climate crisis, which has been conveyed only through numbers, statistics, and shocking spectacle, through the life of an individual experiencing the phenomenon.

This 'subjectivity' aligns with the book's unique perspective: its brilliant way of problematizing climate change as a disaster that directly impacts the lives of the poor, not the rich.

As the author emphasizes, the climate never acts alone.

The climate reveals itself (only) through the lives of workers in brick kilns and garment subcontractors and the urban poor.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Prologue: The Myth of a Sustainable Future 13

Evolution toward Sustainability? 22 | The Profit of Ignorance 33

Part 1: The Dark World of the Global Economy

Chapter 1: 500 Years of the Global Factory: The Economic System That Sweeps Everything 46

The Birth of the Industrial Workforce 55 | The Past and Present of the Apparel Industry 67

Chapter 2: The Trap of "Good Consumption" and "Sustainability": The Abyss of the Supply Chain 78

Greenwashing in Global Factories 92 | The Huge Void of Global Factories 105

Chapter 3: Carbon Colonialism: How Rich Countries Outsource Their Emissions 118

The Geography of the Apparel Industry 129 | The Hidden Truth About Climate Change 135 | Carbon Colonialism 141

Part 2: The Great Inequality of Climate Change

Chapter 4: Climate Instability: Vulnerabilities Created by Global Inequality 152

Signal and Noise 159 | Experiences with Climate Change 171

Chapter 5 Money Talks: Power Relations Surrounding Climate Speech 184

Humans and Nature 194 | The Power of Climate Knowledge 199 | The Power to See 205

Chapter 6: Wolves in Sheep's Clothing: How Corporate Logic Embraces Climate Action 222

Rain Gambling 231 | The Politics of Climate Truth 242

Epilogue: Six Myths That Fuel Carbon Colonialism 257

Six Myths About the Environment 264 | Myth 1 267 | Myth 271 | Myth 3 277 | Myth 4 283 | Myth 5 289 | Myth 6 292 | Ending Carbon Colonialism 295

Week 303

Evolution toward Sustainability? 22 | The Profit of Ignorance 33

Part 1: The Dark World of the Global Economy

Chapter 1: 500 Years of the Global Factory: The Economic System That Sweeps Everything 46

The Birth of the Industrial Workforce 55 | The Past and Present of the Apparel Industry 67

Chapter 2: The Trap of "Good Consumption" and "Sustainability": The Abyss of the Supply Chain 78

Greenwashing in Global Factories 92 | The Huge Void of Global Factories 105

Chapter 3: Carbon Colonialism: How Rich Countries Outsource Their Emissions 118

The Geography of the Apparel Industry 129 | The Hidden Truth About Climate Change 135 | Carbon Colonialism 141

Part 2: The Great Inequality of Climate Change

Chapter 4: Climate Instability: Vulnerabilities Created by Global Inequality 152

Signal and Noise 159 | Experiences with Climate Change 171

Chapter 5 Money Talks: Power Relations Surrounding Climate Speech 184

Humans and Nature 194 | The Power of Climate Knowledge 199 | The Power to See 205

Chapter 6: Wolves in Sheep's Clothing: How Corporate Logic Embraces Climate Action 222

Rain Gambling 231 | The Politics of Climate Truth 242

Epilogue: Six Myths That Fuel Carbon Colonialism 257

Six Myths About the Environment 264 | Myth 1 267 | Myth 271 | Myth 3 277 | Myth 4 283 | Myth 5 289 | Myth 6 292 | Ending Carbon Colonialism 295

Week 303

Into the book

We can see that vulnerability to the risks posed by climate change is by no means inevitable.

This is a function whose outcome depends on choice, or more appropriately, the presence or absence of wealth.

--- p.20

In the geography of disaster risk, money is indispensable.

Countries like Haiti, Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Pakistan face landslides, droughts, floods, and heat waves, and these risks are expected to worsen in the future.

For millions of people, this means disruption to farming and food shortages.

However, the meaning does not necessarily have to be found in these results.

The cause of this lies in a system where the environmental costs associated with wealth creation are paid in places far removed from where the wealth is accumulated.

This system is called carbon colonialism in this book.

--- p.20~21

In a global system, production relies on the classification and recording of goods moving in and out of containers.

And from that point on, we can no longer directly observe the goods.

The path of goods can only be traced through the logbook that records them, and their appearance is revealed only at departure and arrival.

We can't choose anything and we can't see anything.

--- p.103

Environmental pressures have accelerated mechanization, spurred a shift to the garment sector and other industries, and continue to act as stressors on those who remain, straining their livelihoods.

--- p.175

We can learn more about the crisis at the root of climate breakdown through this vast terrain of ignorance than through our own knowledge of the environment.

It's fundamentally a question of power, not technology.

--- p.215

People are realizing that climate change is not a problem of undeveloped technology, but has always been a problem of unequal power.

As the impacts of climate breakdown become clearer, this realization has the potential to transform into a moment of political and social rupture, and ultimately a break with the status quo.

But to unlock this potential, everyone must step up.

This is a function whose outcome depends on choice, or more appropriately, the presence or absence of wealth.

--- p.20

In the geography of disaster risk, money is indispensable.

Countries like Haiti, Myanmar, Bangladesh, and Pakistan face landslides, droughts, floods, and heat waves, and these risks are expected to worsen in the future.

For millions of people, this means disruption to farming and food shortages.

However, the meaning does not necessarily have to be found in these results.

The cause of this lies in a system where the environmental costs associated with wealth creation are paid in places far removed from where the wealth is accumulated.

This system is called carbon colonialism in this book.

--- p.20~21

In a global system, production relies on the classification and recording of goods moving in and out of containers.

And from that point on, we can no longer directly observe the goods.

The path of goods can only be traced through the logbook that records them, and their appearance is revealed only at departure and arrival.

We can't choose anything and we can't see anything.

--- p.103

Environmental pressures have accelerated mechanization, spurred a shift to the garment sector and other industries, and continue to act as stressors on those who remain, straining their livelihoods.

--- p.175

We can learn more about the crisis at the root of climate breakdown through this vast terrain of ignorance than through our own knowledge of the environment.

It's fundamentally a question of power, not technology.

--- p.215

People are realizing that climate change is not a problem of undeveloped technology, but has always been a problem of unequal power.

As the impacts of climate breakdown become clearer, this realization has the potential to transform into a moment of political and social rupture, and ultimately a break with the status quo.

But to unlock this potential, everyone must step up.

--- p.301

Publisher's Review

On the massive inequality of the climate crisis

Behind ‘sustainability’ and ‘eco-friendliness’

The ugly faces of hypocrisy that sell disaster

“The climate never acts alone.

“Climate meets humans wearing the clothes of society.”

Can so-called "ethical consumption" practices like zero waste and reducing plastic use prevent the climate crisis? If so, why is the climate catastrophe worsening and accelerating? Global companies are churning out products with slogans and labels like "sustainability," "green growth," "fair trade," "eco-friendly," and "organic," and consumers' calls for "ethical production" are louder than ever.

But the reality is actually going in the opposite direction.

Geographer Laurie Parsons, who consistently writes from a labor perspective, casts strong doubts on such a "green outlook" and uncovers the truth hidden by global supply chains.

In an era of global production, where goods are no longer produced in a single country, how meaningless is it to advocate for "carbon reduction" solely based on domestic carbon emissions? Corporations relocate factories to poorer countries, selling off environmental pollution and climate collapse, while wealthy nations tolerate the ills of such overseas production and continue to only count carbon emissions within their own borders.

This is the reality of their eco-friendly and carbon-reduction efforts.

The author has been conducting field research at several production plants in Southeast Asia (Cambodia) to trace this outdated carbon accounting mechanism.

The starting point of the discussion is to face the fact that environmental degradation and the climate crisis are not neutral natural phenomena, but rather 'massive inequalities.'

Impressively, the author presents the climate crisis, which has been conveyed only through numbers, statistics, and shocking spectacle, through the life of an individual experiencing the phenomenon.

This 'subjectivity' aligns with the book's unique perspective: its brilliant way of problematizing climate change as a disaster that directly impacts the lives of the poor, not the rich.

As the author emphasizes, the climate never acts alone.

The climate reveals itself (only) through the lives of workers in brick kilns and garment subcontractors and the urban poor.

Why 'Good Consumption' Fails: The Illusion of Green Capitalism

“All of this points to a fundamental and core truth about the environment in our globalized world.

In other words, what we know is much less than we think.”

No one can deny that climate change is a fact and a reality anymore.

After the 1970s and 1980s, when scientists engaged in significant debates over the scientific evidence for climate change, and the 1990s and 2000s, when some still questioned whether humans could truly be blamed for global warming, humanity has finally entered the era of "climate consensus."

No one can deny that climate change has already begun, is happening here and now, and is only getting worse.

Until this era of consensus dawned, there were countless disasters such as floods, droughts, heat waves, landslides, and hurricanes, and the Earth's temperature steadily rose every year.

As the landscape of public opinion surrounding climate change shifts, even the companies driving the global economy are no longer immune to pressure.

We are faced with a situation where we have to kill two birds with one stone: economic growth and environmental sustainability.

The solution chosen by global corporations that could not give up economic expansion was, in a word, a disguise called 'greenwashing.'

Greenwashing is a term that criticizes the practices of companies that claim to be environmentally friendly but ultimately continue to operate/produce in a way that is far from that. It is commonly found in advertisements and promotional materials provided by companies.

So to speak, today's environmental discussions are filled with things that only appear sustainable, not things that are truly sustainable.

Moreover, greenwashing techniques are becoming increasingly sophisticated, allowing “today’s newly globalized economy to appear sustainable with minimal effort.”

Consumers are enthusiastic about eco-friendly products, and global companies are responding to these expectations by focusing on promoting their eco-friendly image, regardless of whether it is true or not.

Thanks to this, there are few products sold on the streets of wealthy countries today that do not claim to be environmentally friendly.

This is the illusion of green capitalism.

“However, these claims are nothing more than a fantasy to increase profitability, as they have not been verified.

“At best, it’s greenwashing; at worst, it’s an outright lie.”

Where Nothing Can Be Seen: The Vast Void of the Global Factory

“The fact that a significant portion of the global economy is located thousands of miles from the people who buy its products is already an insurmountable barrier.

This barrier effectively blocks consumers.

“No matter how good the intentions, reality is opaque.”

So how does greenwashing, which derails "good consumption," specifically work? Rather than limiting greenwashing to dubious or outright false claims that companies and brands often embed in their product advertising, Lori Parsons analyzes it as a fundamental mechanism that powers global production networks.

In other words, greenwashing is not limited to green phrases like “100 percent natural,” “for the ecological era,” “biodegradable,” “recyclable,” and “does not destroy the ozone layer.”

21st-century globalization, anchored in the deep-rooted practices of imperialist extractivism that began in the 17th century, has opened up a new horizon called the "global supply chain" based on its historical foundation.

The supply chains established by empires of the past have become interconnected to an unprecedented degree, thanks to tremendous technological leaps in communications and logistics.

Two key innovations made this international supply chain possible: the introduction of containers as a key mode of transport and the deregulation led by China in the 1970s and 1980s.

Mechanized containers have contributed to steadily lowering standard prices, as they can be loaded, unloaded, and transported by cranes alone, without human labor, while deregulation has enabled companies to build truly global factories (in other countries) by removing restrictions that prevent foreign ownership.

These innovations have enabled wealthy nations to efficiently manage the chain of operations—extracting raw materials, processing goods, and transporting waste back to the global periphery—making cost reduction, rather than distance, a priority.

In this way, global supply chains have transformed the environments of (distant) producing countries to suit the tastes of consuming countries.

This is why production is no longer done locally today.

Global factories located overseas operate through remote monitoring, adjusted by various technical indicators, so there is nothing that can be directly observed with the naked eye.

Unlike a factory (in the traditional sense) that has a physical entity, you cannot see the flow/process through which materials and goods are produced, nor can you directly inspect them as they move.

Even if a brand has the will to conduct inspections, it is largely unreasonable to periodically dispatch a team of inspectors equipped with the necessary inspection equipment to each stop along a long and complex supply chain to conduct meaningful oversight.

When a local broker overseeing the process on behalf of a brand says, "The inspection is being done well," you have no choice but to blindly believe them.

But overseeing a remote location in a far-flung country presents numerous opportunities for brands to deviate from the standards they themselves have set.

What's Happening Behind the 'Eco-Friendly Label': Carbon Colonialism

"What if one place was clean, and the other was destroyed? What if one place was safe, and the other was dangerous?"

Cambodian garment subcontractor workers, whom the author met and interviewed in person, vividly portray the even more horrific truth inside global factories.

The rampant illegal subcontracting, and the hundreds of small factories (actually roadside shacks) that offload this subcontracted labor and the notorious exploitation that takes place there, are presented as being entirely unrelated to the brand's decisions.

But this vast shadow industry, unexplained by the many formalized indicators of rising minimum wages, corporate social responsibility, and best-practice supply chains in recent years, is the true reality of the apparel industry.

This silent labor force, which produces a significant portion of the orders placed by brands, is never mentioned on the labels of the clothes we buy or in any of the various fairness indicators of companies.

The case of Cambodian garment workers highlights the profound distortion of the very landscape of environmental discourse.

Amidst the ongoing trend toward sustainable, fair production and ethical consumption, eco-friendliness continues to gain traction, and even individual countries are achieving massive carbon reductions. Yet, why do atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations continue to soar? Why are disasters becoming more frequent and severe? From the first World Climate Conference in 1979 to the Paris Agreement in 2016, major nations around the world have agreed to policies to reduce carbon emissions through various agreements and conferences, and have actually "clearly" reduced their emissions.

This is a 'fact' proven by 'objective' statistical data, as the European Union alone succeeded in reducing its net carbon dioxide emissions from 5.6 billion tons in 1990 to 4.2 billion tons in 2018.

What lies behind this discrepancy? The author seeks the answer in the unequal historical power relations encapsulated by the term "carbon colonialism."

Carbon colonialism literally refers to the practice of systematically exporting/outsourcing industrial processes that cause more environmental pollution to poor countries in the global south or Southeast Asia.

This is precisely how wealthy, so-called "developed" countries move their carbon emissions off their environmental ledgers.

Of course, they still get to keep the economic benefits of the production process while moving it (which is highly polluting).

The long history of colonialism has evolved even further today, encroaching even on discourse about the environment and climate.

The change we need now is not any consumer practices.

In other words, rather than worrying about which eco-friendly products to take to the checkout counter, we must accurately understand and confront the development process and mechanisms of a global system that supports the easy promotion of eco-friendliness while relying on poor working conditions and cheap, disposable labor.

This is the practice of converting knowledge about products into knowledge about production and supply chains.

The Vicious Cycle: The Truth Beyond the Statistics

“The experiences we share, the environments in which we work and live, the specific pressures we face in life—all of these shape how we perceive the world around us.”

“The climate never acts alone.

Climate meets humans wearing the clothes of society.

Climate appears in the form of governance systems and economies, as well as in the form of norms, morals, and beliefs.

These two spheres of human experience work together to determine who will suffer most, who will suffer least, and who will be the winners of climate breakdown.”

The truth about the global production system and the carbon colonialism hidden within it reminds us that we must think about the human crisis from a completely new perspective.

Carbon colonialism is the latest form of imperialist violence, trampling and destroying one world for another, exposing the vast inequalities concealed by individual countries' carbon emissions and carbon reduction rates.

While wealthy countries promote cleanliness and environmental friendliness through global production, the costs of that production (carbon and waste) are transferred to poorer countries, gradually destroying the local environment there.

The impacts of climate change, including disasters, are traded in a way that wealthier countries export them and less wealthy countries import them as a price for economic growth.

This is how the global economy worsens climate change.

As long as that mechanism is in operation, climate change cannot be a neutral natural phenomenon.

Experiences of climate change are deeply connected to social status and the amount of money one has, both at the national level and in one's own life.

At its simplest, the cold is a completely different world for those who can afford to heat their homes and those who cannot.

This subjectivity that conditions our experience of climate change is perhaps the least understood aspect of climate change, yet it reveals crucial aspects that scientific metrics like physical quantities and statistics fail to capture.

When most ordinary people talk about climate, they primarily relate it to what they do, that is, what kind of livelihood they engage in.

Just as fishermen who make a living by fishing in the lake and small-scale farmers who farm do not experience climate change in the same way.

A fisherman would talk about the change in wind, but a farmer would emphasize the severity of the drought.

In this way, climate is still experienced as “the climate that a person immediately faces, such as weather in general, air quality, and rainfall quality.”

That is why the author goes beyond the scientific concept of climate or environmental information expressed in statistical indicators or objective figures, and focuses on the detailed lives of bricklayers, farmers, and the urban poor.

If climate is as much a cultural concept as it is a scientific one, and if this is how we all experience our own climate, then discussing climate is ultimately about talking about the context in which we live.

Even climate science is subjective in some sense.

Climate scientists also assess the timeframe, scale, and aspects they consider relevant.

The farmers and workers the author met during his fieldwork convey an obvious but often overlooked point: “The subtle and complex ways in which climate change intertwines with the economics of daily life and work are missed in statistics.”

Climate change, such as droughts, floods, heat waves, and global warming, is forcing farmers into a swamp of loans and debt (since mechanized farming forces them to buy machines) or, worse, forcing them to abandon their land and become industrial workers.

And in the process, some people become streetwalkers in the city.

This vicious cycle, in which a changing environment forces people off the land, those people flock to factories, and those factories, in turn, destroy the rural environment, will only worsen in the future.

This process is upending the world as it experiences climate change, reshaping the landscape itself and reconfiguring working conditions accordingly.

This is what climate change means to people.

“Climate change isn’t just experienced as catastrophic floods, endless droughts reminiscent of the Dust Bowl, or heat waves that leave people collapsing and dying on the streets.

Climate change means crop failures and food shortages, and for the vast majority of people, it is experienced as increasing pressure, increasingly powerful pressures, reduced bargaining power, and worsening working conditions.”

Power Relations Surrounding Climate Talk: How Not Knowing Becomes Power

“Knowledge is power.

But whose power is it? What power is it? How does knowledge shape the environment?

“Like other forms of knowledge, climate knowledge is power.”

And the power of wealth isn't just a story about the experience of climate change.

At a more fundamental level, it touches on the 'power of speech' or 'power of language' – the power to choose the terms used in climate discussions and decide which issues are presented as important or unimportant.

In this respect, what the author wants to talk about through “Geography of Disaster” is by no means the climate crisis or environmental issues themselves.

What is truly being overlooked is the underlying framework that problematizes such natural phenomena: the problem inherent in today's environmentalism.

“Protecting the environment is, at a deeper level, a matter of defining what is valuable, how, and for whom.

What cannot be defined cannot be protected.

But the power to define what needs protection is grossly unequal.”

The power to define what is protected or to establish our relationship with nature is strictly economic.

Ultimately, poor countries will have no choice but to fully embrace the neoliberal development model, putting their natural assets on the global market and even ceding control over their value.

It is the wealthy and powerful nations that devise the terms to describe our relationship with nature, and it is they who have the say in defining the environment.

As the author emphasizes, the Earth we know now, and the climate and environmental knowledge we have, is knowledge that has 'already' been 'determined' that we need to know.

In other words, the power to determine what we need to know is already at work here.

“The human environment holds a story of countless side effects, of things that are irrelevant, of things that ‘we’ do not need to know about, of an endless legacy left behind.

The Earth that humans live on is an Earth we do not know.

It is the invisible, unintended, unwanted shadow of everything we do.”

This means that when discussing the climate crisis, what we need is not the environmental knowledge we already have, but this 'vast terrain of ignorance.'

This terrain of ignorance, which most people are unaware of, speaks volumes about the crisis at the root of climate breakdown.

“It’s not fundamentally a question of technology, it’s a question of power.

Power has to do with the frameworks we have for understanding the world, what we can see through those frameworks, and what remains invisible because we lack the tools to grasp it.”

Every day, we visit various stores, select various products, and place them on the checkout counter.

And most of these products are engraved with various types of eco-friendly marks and labels indicating the country of origin or manufacturing.

Such information often lulls our consumers into the illusion that they have clear and transparent knowledge about the product.

But we know nothing.

Where did harmless items we use on a daily basis, like clothing or bricks, get here, what path did they take, and what twists and turns did they encounter along the way?

What we need now is not the kind of generic knowledge manufactured within the framework of power, that is, knowledge about commodities.

Unless we investigate how such seemingly harmless items are implicated in serious environmental destruction and climate change, the crucial truth behind labels and claims will remain hidden forever.

It's so easy and convenient to hide all the ugly things that happen during the production process and pretend to be 'eco-friendly' and 'sustainable'.

So, that fantasy is the new front line of the climate crisis.

We must transform the climate debate by calling those empty slogans the terrain of "ignorance" rather than "knowledge."

Behind ‘sustainability’ and ‘eco-friendliness’

The ugly faces of hypocrisy that sell disaster

“The climate never acts alone.

“Climate meets humans wearing the clothes of society.”

Can so-called "ethical consumption" practices like zero waste and reducing plastic use prevent the climate crisis? If so, why is the climate catastrophe worsening and accelerating? Global companies are churning out products with slogans and labels like "sustainability," "green growth," "fair trade," "eco-friendly," and "organic," and consumers' calls for "ethical production" are louder than ever.

But the reality is actually going in the opposite direction.

Geographer Laurie Parsons, who consistently writes from a labor perspective, casts strong doubts on such a "green outlook" and uncovers the truth hidden by global supply chains.

In an era of global production, where goods are no longer produced in a single country, how meaningless is it to advocate for "carbon reduction" solely based on domestic carbon emissions? Corporations relocate factories to poorer countries, selling off environmental pollution and climate collapse, while wealthy nations tolerate the ills of such overseas production and continue to only count carbon emissions within their own borders.

This is the reality of their eco-friendly and carbon-reduction efforts.

The author has been conducting field research at several production plants in Southeast Asia (Cambodia) to trace this outdated carbon accounting mechanism.

The starting point of the discussion is to face the fact that environmental degradation and the climate crisis are not neutral natural phenomena, but rather 'massive inequalities.'

Impressively, the author presents the climate crisis, which has been conveyed only through numbers, statistics, and shocking spectacle, through the life of an individual experiencing the phenomenon.

This 'subjectivity' aligns with the book's unique perspective: its brilliant way of problematizing climate change as a disaster that directly impacts the lives of the poor, not the rich.

As the author emphasizes, the climate never acts alone.

The climate reveals itself (only) through the lives of workers in brick kilns and garment subcontractors and the urban poor.

Why 'Good Consumption' Fails: The Illusion of Green Capitalism

“All of this points to a fundamental and core truth about the environment in our globalized world.

In other words, what we know is much less than we think.”

No one can deny that climate change is a fact and a reality anymore.

After the 1970s and 1980s, when scientists engaged in significant debates over the scientific evidence for climate change, and the 1990s and 2000s, when some still questioned whether humans could truly be blamed for global warming, humanity has finally entered the era of "climate consensus."

No one can deny that climate change has already begun, is happening here and now, and is only getting worse.

Until this era of consensus dawned, there were countless disasters such as floods, droughts, heat waves, landslides, and hurricanes, and the Earth's temperature steadily rose every year.

As the landscape of public opinion surrounding climate change shifts, even the companies driving the global economy are no longer immune to pressure.

We are faced with a situation where we have to kill two birds with one stone: economic growth and environmental sustainability.

The solution chosen by global corporations that could not give up economic expansion was, in a word, a disguise called 'greenwashing.'

Greenwashing is a term that criticizes the practices of companies that claim to be environmentally friendly but ultimately continue to operate/produce in a way that is far from that. It is commonly found in advertisements and promotional materials provided by companies.

So to speak, today's environmental discussions are filled with things that only appear sustainable, not things that are truly sustainable.

Moreover, greenwashing techniques are becoming increasingly sophisticated, allowing “today’s newly globalized economy to appear sustainable with minimal effort.”

Consumers are enthusiastic about eco-friendly products, and global companies are responding to these expectations by focusing on promoting their eco-friendly image, regardless of whether it is true or not.

Thanks to this, there are few products sold on the streets of wealthy countries today that do not claim to be environmentally friendly.

This is the illusion of green capitalism.

“However, these claims are nothing more than a fantasy to increase profitability, as they have not been verified.

“At best, it’s greenwashing; at worst, it’s an outright lie.”

Where Nothing Can Be Seen: The Vast Void of the Global Factory

“The fact that a significant portion of the global economy is located thousands of miles from the people who buy its products is already an insurmountable barrier.

This barrier effectively blocks consumers.

“No matter how good the intentions, reality is opaque.”

So how does greenwashing, which derails "good consumption," specifically work? Rather than limiting greenwashing to dubious or outright false claims that companies and brands often embed in their product advertising, Lori Parsons analyzes it as a fundamental mechanism that powers global production networks.

In other words, greenwashing is not limited to green phrases like “100 percent natural,” “for the ecological era,” “biodegradable,” “recyclable,” and “does not destroy the ozone layer.”

21st-century globalization, anchored in the deep-rooted practices of imperialist extractivism that began in the 17th century, has opened up a new horizon called the "global supply chain" based on its historical foundation.

The supply chains established by empires of the past have become interconnected to an unprecedented degree, thanks to tremendous technological leaps in communications and logistics.

Two key innovations made this international supply chain possible: the introduction of containers as a key mode of transport and the deregulation led by China in the 1970s and 1980s.

Mechanized containers have contributed to steadily lowering standard prices, as they can be loaded, unloaded, and transported by cranes alone, without human labor, while deregulation has enabled companies to build truly global factories (in other countries) by removing restrictions that prevent foreign ownership.

These innovations have enabled wealthy nations to efficiently manage the chain of operations—extracting raw materials, processing goods, and transporting waste back to the global periphery—making cost reduction, rather than distance, a priority.

In this way, global supply chains have transformed the environments of (distant) producing countries to suit the tastes of consuming countries.

This is why production is no longer done locally today.

Global factories located overseas operate through remote monitoring, adjusted by various technical indicators, so there is nothing that can be directly observed with the naked eye.

Unlike a factory (in the traditional sense) that has a physical entity, you cannot see the flow/process through which materials and goods are produced, nor can you directly inspect them as they move.

Even if a brand has the will to conduct inspections, it is largely unreasonable to periodically dispatch a team of inspectors equipped with the necessary inspection equipment to each stop along a long and complex supply chain to conduct meaningful oversight.

When a local broker overseeing the process on behalf of a brand says, "The inspection is being done well," you have no choice but to blindly believe them.

But overseeing a remote location in a far-flung country presents numerous opportunities for brands to deviate from the standards they themselves have set.

What's Happening Behind the 'Eco-Friendly Label': Carbon Colonialism

"What if one place was clean, and the other was destroyed? What if one place was safe, and the other was dangerous?"

Cambodian garment subcontractor workers, whom the author met and interviewed in person, vividly portray the even more horrific truth inside global factories.

The rampant illegal subcontracting, and the hundreds of small factories (actually roadside shacks) that offload this subcontracted labor and the notorious exploitation that takes place there, are presented as being entirely unrelated to the brand's decisions.

But this vast shadow industry, unexplained by the many formalized indicators of rising minimum wages, corporate social responsibility, and best-practice supply chains in recent years, is the true reality of the apparel industry.

This silent labor force, which produces a significant portion of the orders placed by brands, is never mentioned on the labels of the clothes we buy or in any of the various fairness indicators of companies.

The case of Cambodian garment workers highlights the profound distortion of the very landscape of environmental discourse.

Amidst the ongoing trend toward sustainable, fair production and ethical consumption, eco-friendliness continues to gain traction, and even individual countries are achieving massive carbon reductions. Yet, why do atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations continue to soar? Why are disasters becoming more frequent and severe? From the first World Climate Conference in 1979 to the Paris Agreement in 2016, major nations around the world have agreed to policies to reduce carbon emissions through various agreements and conferences, and have actually "clearly" reduced their emissions.

This is a 'fact' proven by 'objective' statistical data, as the European Union alone succeeded in reducing its net carbon dioxide emissions from 5.6 billion tons in 1990 to 4.2 billion tons in 2018.

What lies behind this discrepancy? The author seeks the answer in the unequal historical power relations encapsulated by the term "carbon colonialism."

Carbon colonialism literally refers to the practice of systematically exporting/outsourcing industrial processes that cause more environmental pollution to poor countries in the global south or Southeast Asia.

This is precisely how wealthy, so-called "developed" countries move their carbon emissions off their environmental ledgers.

Of course, they still get to keep the economic benefits of the production process while moving it (which is highly polluting).

The long history of colonialism has evolved even further today, encroaching even on discourse about the environment and climate.

The change we need now is not any consumer practices.

In other words, rather than worrying about which eco-friendly products to take to the checkout counter, we must accurately understand and confront the development process and mechanisms of a global system that supports the easy promotion of eco-friendliness while relying on poor working conditions and cheap, disposable labor.

This is the practice of converting knowledge about products into knowledge about production and supply chains.

The Vicious Cycle: The Truth Beyond the Statistics

“The experiences we share, the environments in which we work and live, the specific pressures we face in life—all of these shape how we perceive the world around us.”

“The climate never acts alone.

Climate meets humans wearing the clothes of society.

Climate appears in the form of governance systems and economies, as well as in the form of norms, morals, and beliefs.

These two spheres of human experience work together to determine who will suffer most, who will suffer least, and who will be the winners of climate breakdown.”

The truth about the global production system and the carbon colonialism hidden within it reminds us that we must think about the human crisis from a completely new perspective.

Carbon colonialism is the latest form of imperialist violence, trampling and destroying one world for another, exposing the vast inequalities concealed by individual countries' carbon emissions and carbon reduction rates.

While wealthy countries promote cleanliness and environmental friendliness through global production, the costs of that production (carbon and waste) are transferred to poorer countries, gradually destroying the local environment there.

The impacts of climate change, including disasters, are traded in a way that wealthier countries export them and less wealthy countries import them as a price for economic growth.

This is how the global economy worsens climate change.

As long as that mechanism is in operation, climate change cannot be a neutral natural phenomenon.

Experiences of climate change are deeply connected to social status and the amount of money one has, both at the national level and in one's own life.

At its simplest, the cold is a completely different world for those who can afford to heat their homes and those who cannot.

This subjectivity that conditions our experience of climate change is perhaps the least understood aspect of climate change, yet it reveals crucial aspects that scientific metrics like physical quantities and statistics fail to capture.

When most ordinary people talk about climate, they primarily relate it to what they do, that is, what kind of livelihood they engage in.

Just as fishermen who make a living by fishing in the lake and small-scale farmers who farm do not experience climate change in the same way.

A fisherman would talk about the change in wind, but a farmer would emphasize the severity of the drought.

In this way, climate is still experienced as “the climate that a person immediately faces, such as weather in general, air quality, and rainfall quality.”

That is why the author goes beyond the scientific concept of climate or environmental information expressed in statistical indicators or objective figures, and focuses on the detailed lives of bricklayers, farmers, and the urban poor.

If climate is as much a cultural concept as it is a scientific one, and if this is how we all experience our own climate, then discussing climate is ultimately about talking about the context in which we live.

Even climate science is subjective in some sense.

Climate scientists also assess the timeframe, scale, and aspects they consider relevant.

The farmers and workers the author met during his fieldwork convey an obvious but often overlooked point: “The subtle and complex ways in which climate change intertwines with the economics of daily life and work are missed in statistics.”

Climate change, such as droughts, floods, heat waves, and global warming, is forcing farmers into a swamp of loans and debt (since mechanized farming forces them to buy machines) or, worse, forcing them to abandon their land and become industrial workers.

And in the process, some people become streetwalkers in the city.

This vicious cycle, in which a changing environment forces people off the land, those people flock to factories, and those factories, in turn, destroy the rural environment, will only worsen in the future.

This process is upending the world as it experiences climate change, reshaping the landscape itself and reconfiguring working conditions accordingly.

This is what climate change means to people.

“Climate change isn’t just experienced as catastrophic floods, endless droughts reminiscent of the Dust Bowl, or heat waves that leave people collapsing and dying on the streets.

Climate change means crop failures and food shortages, and for the vast majority of people, it is experienced as increasing pressure, increasingly powerful pressures, reduced bargaining power, and worsening working conditions.”

Power Relations Surrounding Climate Talk: How Not Knowing Becomes Power

“Knowledge is power.

But whose power is it? What power is it? How does knowledge shape the environment?

“Like other forms of knowledge, climate knowledge is power.”

And the power of wealth isn't just a story about the experience of climate change.

At a more fundamental level, it touches on the 'power of speech' or 'power of language' – the power to choose the terms used in climate discussions and decide which issues are presented as important or unimportant.

In this respect, what the author wants to talk about through “Geography of Disaster” is by no means the climate crisis or environmental issues themselves.

What is truly being overlooked is the underlying framework that problematizes such natural phenomena: the problem inherent in today's environmentalism.

“Protecting the environment is, at a deeper level, a matter of defining what is valuable, how, and for whom.

What cannot be defined cannot be protected.

But the power to define what needs protection is grossly unequal.”

The power to define what is protected or to establish our relationship with nature is strictly economic.

Ultimately, poor countries will have no choice but to fully embrace the neoliberal development model, putting their natural assets on the global market and even ceding control over their value.

It is the wealthy and powerful nations that devise the terms to describe our relationship with nature, and it is they who have the say in defining the environment.

As the author emphasizes, the Earth we know now, and the climate and environmental knowledge we have, is knowledge that has 'already' been 'determined' that we need to know.

In other words, the power to determine what we need to know is already at work here.

“The human environment holds a story of countless side effects, of things that are irrelevant, of things that ‘we’ do not need to know about, of an endless legacy left behind.

The Earth that humans live on is an Earth we do not know.

It is the invisible, unintended, unwanted shadow of everything we do.”

This means that when discussing the climate crisis, what we need is not the environmental knowledge we already have, but this 'vast terrain of ignorance.'

This terrain of ignorance, which most people are unaware of, speaks volumes about the crisis at the root of climate breakdown.

“It’s not fundamentally a question of technology, it’s a question of power.

Power has to do with the frameworks we have for understanding the world, what we can see through those frameworks, and what remains invisible because we lack the tools to grasp it.”

Every day, we visit various stores, select various products, and place them on the checkout counter.

And most of these products are engraved with various types of eco-friendly marks and labels indicating the country of origin or manufacturing.

Such information often lulls our consumers into the illusion that they have clear and transparent knowledge about the product.

But we know nothing.

Where did harmless items we use on a daily basis, like clothing or bricks, get here, what path did they take, and what twists and turns did they encounter along the way?

What we need now is not the kind of generic knowledge manufactured within the framework of power, that is, knowledge about commodities.

Unless we investigate how such seemingly harmless items are implicated in serious environmental destruction and climate change, the crucial truth behind labels and claims will remain hidden forever.

It's so easy and convenient to hide all the ugly things that happen during the production process and pretend to be 'eco-friendly' and 'sustainable'.

So, that fantasy is the new front line of the climate crisis.

We must transform the climate debate by calling those empty slogans the terrain of "ignorance" rather than "knowledge."

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 2, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 324 pages | 392g | 135*205*22mm

- ISBN13: 9791168731233

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)