Completely equal and extremely discriminatory

|

Description

Book Introduction

Kim Won-young, known to readers as a lawyer and author of 『A Defense for the Disqualified』 and 『Becoming a Cyborg』 (co-authored).

In the former, there is a heated debate on the legal and social rights of minorities, and in the latter, the bodies of the disabled. He, who has been thinking about another identity created through the combination of technology, has returned with a new theme of 'body, dance, and equality.' "Completely Equal and Extremely Discriminatory" is a record of his journey from lawyer to dancer, exploring the relationship between discrimination and equality, a subject he has long explored, through the questions he faced as a disabled person and the history of dance. Beginning with a look at the emergence of 'unusual' bodies in the history of dance, it goes beyond the Eastern and Western dance world's other figures, such as Choi Seung-hee and Nijinsky, to vividly address the voices of disabled dance troupes and dance teams that created their own unique contemporary trends, restoring the presence of forgotten others on stage. This book, which examines the order engraved in the body and the scenes of overturning that order, focusing on asymmetrical power relations such as normal and abnormal, majority and minority, East and West, will propose a bold imagination for an equal stage (community) created by different bodies. It is thanks to witnessing that not only the order engraved in our bodies, but also that sometimes just slightly twisting that order or creating a new order can open a stage for hospitality. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

ㆍEntering / Between equal power and differential ability

Part 1 Into the Light

On the first tightrope

Second Freak Show

Inside and Outside of the Third Gaze

The Fourth Dance of the Sick Bodies

Part 2: Opening a Closed World

A theater without a fifth wall

Don't wait for the sixth altitude

Becoming a Part 3 Dancer

The Seventh Spring Explosion

Democracy of the Eighth Dance

Become the ninth dancer

Acknowledgements

Americas

Part 1 Into the Light

On the first tightrope

Second Freak Show

Inside and Outside of the Third Gaze

The Fourth Dance of the Sick Bodies

Part 2: Opening a Closed World

A theater without a fifth wall

Don't wait for the sixth altitude

Becoming a Part 3 Dancer

The Seventh Spring Explosion

Democracy of the Eighth Dance

Become the ninth dancer

Acknowledgements

Americas

Detailed image

Into the book

The painful truth that rises from within deceives us.

You have to open your eyes, open the door, and step into the light shining outside.

There my body will be subject to discrimination, contempt, and disdain.

If so, you need to learn the techniques of hiding as much as possible, moving less, and controlling well.

--- From "On a Tightrope"

If I had tried to conceal my disability by wearing cultural and intellectual badges and trying to disguise myself as a "normal, ordinary citizen" as best I could, the Frick boy of 1895 had no such option.

Rather, he faces his own transformed body head-on to survive reality, and takes the path of maximizing monstrosity, savagery, mystery, and strangeness.

This will require much more courage than hiding your disability.

I cannot imagine a way to attract the public's blatant gaze toward oneself as intensely as if a magnifying glass were focused on the sun's heat.

--- From "Freak Show"

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the world called various beings called 'others', including Freak, to the center of the world, and within them, some experienced liberation and subversion, others oppression and exploitation, or both.

Because dancers stand before the public with their whole bodies, they are particularly prominent in the midst of the forces of desire and exclusion that surround the other.

--- From "Freak Show"

When we create a strange and creatively unexpected moment in front of the 'gaze' that captures, trades, mocks, exploits, hates, sympathizes, and desires, that is, when we discover ourselves as a body that cannot possibly be captured, traded, mocked, exploited, hated, pitied, or desired, we all open the door to a world we have never imagined before.

The person looking and the person being looked at enter into a completely different relationship than before.

--- From "Inside and Outside the Gaze"

The bodies of disabled people are the source of disturbances, big and small, in any public place.

Disability is a condition or state that is likely to be at odds with existing social rules, order, rituals, cultural practices, and public infrastructure.

--- From "Not Waiting for Altitude"

All the performers I've mentioned are artists who have finally found their own unique territory while struggling to relate to their "helpless bodies" in various ways.

They have been criticized for 'speech-shaming' on stage, for harming their health by dancing with their arms and legs, and for wearing leotards on top of their uncontrolled bodies.

In the process, I proved that I could do the unexpected even with a disabled body, and I was frustrated by the fact that there were things I simply could not do.

Perhaps good dancing (acting) comes from the coexistence of the fundamental attitude that one cannot dance everything while simultaneously realizing that a disability is not a defect that prevents one from dancing?

--- From "Not Waiting for Altitude"

Dancing is a highly sophisticated art, allowing us to transcend the various norms that bind us and willingly become part of a wondrous moment, while remaining aware of objective external circumstances, conditions, and the presence of others, and connecting with that world.

It takes training to master this.

I will suggest one method later that will help you with this skill.

But before that, I want to emphasize that the art we are training in is not just about good dancing or creating wonderful personal experiences; it is also about preventing violence in a very political and communal way.

--- From "Democracy of Dance"

That is how the history of dance began for people with disabilities to enter the field.

It wasn't a truly revolutionary disabled dancer who opened up the door to a courageous, existential challenge.

In the mid-20th century, when the era of great and heroic genius artists was coming to an end, dancers began to 'ride' each other's bodies.

Disabled dancers were able to open the door to the dance world because they were experts in this 'riding' on a daily basis.

Instead of artists who rush to ruin alone, overcome by fever, and drown in the river, people who hold the hands of others and ride the waves have emerged.

As we began to actively engage with each other, the stage was soon set.

You have to open your eyes, open the door, and step into the light shining outside.

There my body will be subject to discrimination, contempt, and disdain.

If so, you need to learn the techniques of hiding as much as possible, moving less, and controlling well.

--- From "On a Tightrope"

If I had tried to conceal my disability by wearing cultural and intellectual badges and trying to disguise myself as a "normal, ordinary citizen" as best I could, the Frick boy of 1895 had no such option.

Rather, he faces his own transformed body head-on to survive reality, and takes the path of maximizing monstrosity, savagery, mystery, and strangeness.

This will require much more courage than hiding your disability.

I cannot imagine a way to attract the public's blatant gaze toward oneself as intensely as if a magnifying glass were focused on the sun's heat.

--- From "Freak Show"

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the world called various beings called 'others', including Freak, to the center of the world, and within them, some experienced liberation and subversion, others oppression and exploitation, or both.

Because dancers stand before the public with their whole bodies, they are particularly prominent in the midst of the forces of desire and exclusion that surround the other.

--- From "Freak Show"

When we create a strange and creatively unexpected moment in front of the 'gaze' that captures, trades, mocks, exploits, hates, sympathizes, and desires, that is, when we discover ourselves as a body that cannot possibly be captured, traded, mocked, exploited, hated, pitied, or desired, we all open the door to a world we have never imagined before.

The person looking and the person being looked at enter into a completely different relationship than before.

--- From "Inside and Outside the Gaze"

The bodies of disabled people are the source of disturbances, big and small, in any public place.

Disability is a condition or state that is likely to be at odds with existing social rules, order, rituals, cultural practices, and public infrastructure.

--- From "Not Waiting for Altitude"

All the performers I've mentioned are artists who have finally found their own unique territory while struggling to relate to their "helpless bodies" in various ways.

They have been criticized for 'speech-shaming' on stage, for harming their health by dancing with their arms and legs, and for wearing leotards on top of their uncontrolled bodies.

In the process, I proved that I could do the unexpected even with a disabled body, and I was frustrated by the fact that there were things I simply could not do.

Perhaps good dancing (acting) comes from the coexistence of the fundamental attitude that one cannot dance everything while simultaneously realizing that a disability is not a defect that prevents one from dancing?

--- From "Not Waiting for Altitude"

Dancing is a highly sophisticated art, allowing us to transcend the various norms that bind us and willingly become part of a wondrous moment, while remaining aware of objective external circumstances, conditions, and the presence of others, and connecting with that world.

It takes training to master this.

I will suggest one method later that will help you with this skill.

But before that, I want to emphasize that the art we are training in is not just about good dancing or creating wonderful personal experiences; it is also about preventing violence in a very political and communal way.

--- From "Democracy of Dance"

That is how the history of dance began for people with disabilities to enter the field.

It wasn't a truly revolutionary disabled dancer who opened up the door to a courageous, existential challenge.

In the mid-20th century, when the era of great and heroic genius artists was coming to an end, dancers began to 'ride' each other's bodies.

Disabled dancers were able to open the door to the dance world because they were experts in this 'riding' on a daily basis.

Instead of artists who rush to ruin alone, overcome by fever, and drown in the river, people who hold the hands of others and ride the waves have emerged.

As we began to actively engage with each other, the stage was soon set.

--- From "Becoming a Dancer"

Publisher's Review

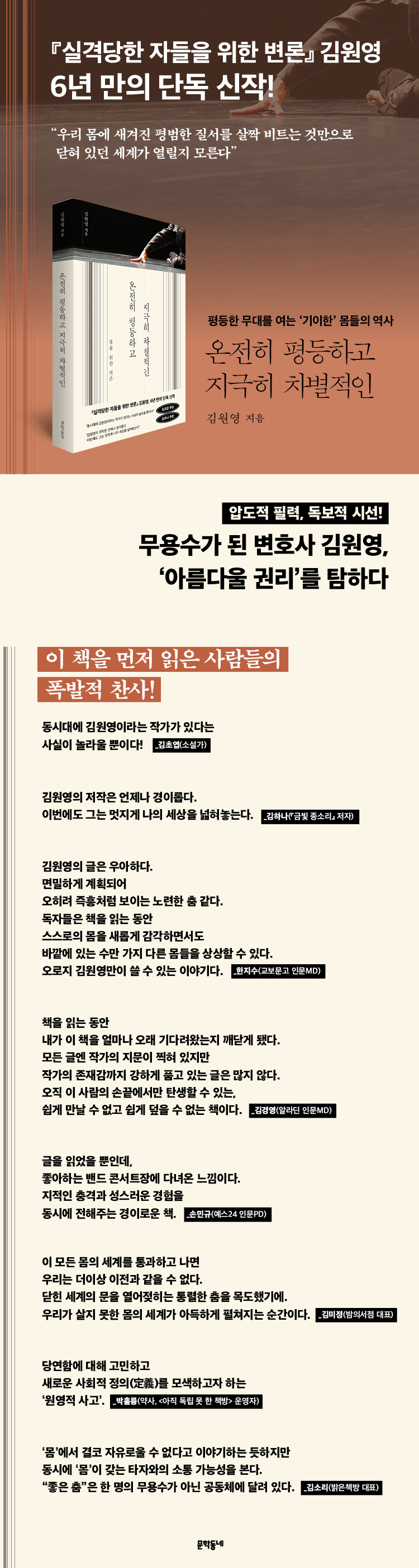

"A Defense of the Disqualified," Kim Won-young's first solo work in six years.

Is 'equality of opportunity for beauty' available to everyone?

A lawyer turned dancer pleads for her body

Kim Won-young, known to readers as a lawyer and author of 『A Defense for the Disqualified』 and 『Becoming a Cyborg』 (co-authored).

In the former, there is a heated debate on the legal and social rights of minorities, and in the latter, the bodies of the disabled.

He has been thinking about another identity created through the combination of technology, and this time he has returned with a new question.

Is ‘equal opportunity to be beautiful’ allowed to those with so-called ‘abnormal bodies’?

Even as minorities strive to affirm their dignity and enshrine it in law and institutions, they cannot avoid one remaining question:

'Can I be an attractive being in and of myself (without relying on law, morality, education, or human rights awareness)?'

He confesses.

Although he has criticized discrimination against the disabled and advocated for their equality as a political entity, he has not been able to affirm his own body for a long time.

I was secretly amazed by the “efficiency of the body without disabilities” and thought that the “efficient, fast, and balanced bodies of non-disabled people were beautiful.”

But about 10 years ago, when he got on stage and started moving his body, Kim Won-young began to awaken to “the experience of becoming the most vivid version of himself” and the sense of “existing as himself.”

After realizing the 'power' within his own body through the process of revealing it rather than hiding it, he no longer disguised himself as a non-disabled person.

In the realm of dance, where physical presence is more crucial than in any other art form, what kind of experiences has Kim Won-young, who has a disability, endured? Kim Won-young, who left her life as a lawyer, where her body could be hidden, to become a dancer, revealing her ample chest and slender legs.

His body is the place where fiery thoughts begin.

What exactly is beauty? Have "abnormal" bodies ever graced the stage throughout history? How did they respond to the gaze of their contemporaries, and what did they desire? What kind of stage presence are contemporary disabled dancers creating? Why is accessibility to art, including dance, important not only for people with disabilities but also for people without disabilities?

"Completely Equal and Extremely Discriminatory" is a record of Kim Won-young's exploration of the relationship between discrimination and equality, restoring the presence of forgotten others on stage through personal experiences and the history of dance.

Beginning with a look at the emergence of "unusual" bodies in the history of dance, the film vividly addresses the voices of domestic and international disabled dance troupes and dance teams in the late 20th century, calling upon others from both the Eastern and Western dance worlds, such as Choi Seung-hee and Nijinsky, and further creating their own unique styles.

This book, which examines the order engraved in the body and the scenes of overturning that order, focusing on asymmetrical power relations such as normal and abnormal, majority and minority, East and West, will propose a bold imagination for an equal stage (community) created by different bodies.

It is thanks to witnessing that not only the order engraved in our bodies, but also that sometimes just slightly twisting that order or creating a new order can open a stage for hospitality.

Above all, this book, "A Defense for the Body," reminds us that, in moving toward a world beyond the familiar order, we must ultimately pay attention to the possibilities of specific bodies.

‘Trust in oneself’ is impossible without ‘trust in one’s body,’ and the relationship one has with one’s own body becomes the basis of one’s relationship with the community.

If I continue to make conscious efforts to protect, guard, and hide this body from the gaze of others, violence, and physical accidents without being able to feel and experience the world with my body itself, it will be difficult for me to reach the limit of my body's (=myself's) potential capacity within the situation I am in.

(...) to the point where I forget that I am the 'source' from which my body operates.

The experience of losing ‘me’ and allowing the ‘body’ to become the most vivid version of me.

A boy with a bulging chest who can crawl on the floor but cannot walk has no idea how far his body can move.

I don't know what my body can and can't do.

_「On a Tightrope」, pp. 32-33

From freak show to retard dance,

Even today, we meet dancers with disabilities.

A History of 'Strange' Bodies that Open the Stage for Equality

Can you picture a disabled body dancing on stage? Whether you picture a ballerina or a K-pop dancer, it's likely not a disabled person.

What about the history of dance? Has there ever been a time when sick bodies, "strange" bodies, appeared? Kim Won-young focuses on the freak shows of the modern exhibition culture of the 19th and early 20th centuries as a space where such bodies were revealed.

In the heart of 19th-century imperialism, curiosity about exotic civilizations in the periphery grew, and 'people' quickly delivered along with flora and fauna from distant lands began to appear as exhibits in commercialized 'freak shows.'

Freaks are usually non-European immigrants, people with disabilities, and people with unusual bodies, but Kim Won-young's perspective on freak shows is somewhat complicated.

While freak shows are clearly sites of violence and exploitation with a history of racial and ableist discrimination, they are also places where socially excluded bodies can engage professionally and influence the public.

While maintaining a critical attitude towards the context in which the freak show was held, he wants to remember the courage of the freaks who faced contempt and exclusion, and the pride of not giving up self-respect amidst all that.

Meanwhile, in the tradition of Korean dance, the most representative dance performed by people with disabilities is the 'Byeongsin Dance'.

How did the "Byeongsin Dance" appeal to the author, who has a "sick body"? The idea that this dance degrades and mocks people with disabilities has long been a concern, and disability groups even raised criticism of the dance in the 1980s.

Of course, opinions are divided, ranging from the view that the disabled dance is a dance of 'human liberation' to the view that the common people objectify the disabled, who are weaker than themselves, as a means of liberation.

Rather than jumping to conclusions about the dance of the disabled, the author examines various perspectives and questions the existence of the subject performing this dance.

The Miryang Baekjungnori performers that I have seen on video sometimes acted exaggeratedly and comically at certain moments, but for the most part, they realistically imitated the body movements down to the smallest detail.

But they didn't seem like real 'idiots' who danced in a spirited manner, liberated from the world's authority, order, and people's gaze ('stares').

They were 'handicapped performers' who meticulously imitated the disabled.

What I found in their acting and dancing were not abstract, expressive gestures that overturned the hierarchical, physical, and cultural order and symbolized human liberation and harmony.

It was a daily gesture that the senior I spoke to in the break room had been making, and it was an image that was reproduced through effective imitation.

(...) If there is no 'disabled person' who dances the 'disabled dance' for whatever reason, I cannot accept the interpretation that this dance is not a dance that simply mocks disability, but rather a dance that breaks free from oppression, reaches enlightenment together, and creates a place for liberation and harmony.

_「Dance of the Sick Bodies」, pp. 118-120

However, as in the example above, 'abnormal' bodies were not only confined to the gaze and constraints of normal people.

In the early 20th century, Korean dancer Choi Seung-hee and Japanese actress Kawakami Sadayako were consumed as colonial and Oriental other, but they sought to confront the dominant gaze surrounding the stage and redefine their ability to dance on their own.

Entering the latter half of the 20th century, we can encounter a growing number of 'other bodies' both domestically and internationally, who create a stir by focusing on the power they possess.

Examples include Kim Man-ri, a Zainichi Korean performer who crawled on stage in a leotard in Kyoto, Japan in the 1980s, asserting the radicalism of uncivilized bodies; the British Candoco Dance Company, which did not hide the physical characteristics of each disabled person—protruding rib cages, amputated legs, etc.—but brought them to the forefront on stage; the Bremen Theater Dance Company in Germany, which sought to reach the experiences of other bodies through choreography that imitated each other's movements; and actor Baek Woo-ram ('Theatre Lover'), who embraced the involuntary movements of his body in his own way rather than controlling them.

Sometimes, they find the rhythm of their words while being 'stuck for words' on stage, and by dancing with both arms as best they can without legs, they easily overcome the prejudice that disability is a flaw that prevents them from dancing.

I accepted that I couldn't dance all the dances, but I found my own unique realm by struggling with my 'helpless body'.

In the process of passing through this diverse world of bodies, the power relations between normal and abnormal are reversed, and readers can witness moments of beauty and wonder in which different bodies exist in their own ways.

When we create a strange and creatively unexpected moment in front of the 'gaze' that captures, trades, mocks, exploits, hates, sympathizes, and desires, that is, when we discover ourselves as a body that cannot possibly be captured, traded, mocked, exploited, hated, pitied, or desired, we all open the door to a world we have never imagined before.

The person looking and the person being looked at enter into a completely different relationship than before.

_「Inside and Outside the Gaze」, p. 97

A Question for a Community of Wonder Where Other Bodies Dance Together

How can 'abnormal bodies' be treated equally?

Our discrimination is more beautiful than your equality.

Let's go back to the original question.

Are "disabled bodies" and non-disabled bodies equal? Are these bodies given equal opportunities to be beautiful? Kim Won-young emphasizes that we are all equal in that we possess "power."

However, power is not synonymous with ability.

Power is the foundation of ability, but it does not remain within one's limitations; it is also the driving force that changes the world's standards of ability.

Thus, although we are in a highly discriminatory relationship because each of us has different abilities, we can achieve complete equality by respecting and trusting each other's strengths.

For example, just because a ballerina doesn't dance ballet in front of Kim Won-young, it doesn't mean that he and the ballerina are equal.

With her ability to dance ballet well, the ballerina can suggest ways to access a world unknown to Kim Won-young.

Meanwhile, Kim Won-young cannot tightrope walk, but he has a "differentiating ability" to rhythmically crawl under a rubber band, and he can invite ballerinas to his performances to suggest other body-becomings (this move is also part of the choreography of "Reality Principle" performed by Kim Won-young).

His 'creeping movements' are the accumulation of a long period of struggle with his body, having been told since childhood, "Don't crawl, don't bulge," and those bodies are connected to the bodies of the people who took care of him, the individuals he met, learned with, and performed on stage with.

Kim Won-young's unique experience leaves a distinctive power in his body, and that power is the root that creates a different world.

For Kim Won-young, dancing is not just a matter of personal pleasure.

The existence of a dancer with a disability is political in itself, as it transcends the norms expected of their bodies, and communal, as it presupposes the existence of others.

Since a community cannot be established without the concept of 'we', it is inevitable that some beings will be excluded. He proposes 'accessibility', a principle of dance, as a new ethics for the community.

As discussed in detail in Part 2, “Opening a Closed World,” accessibility in the field of dance means installing barrier-free devices in the audience and attempts to enable various movements on stage. However, he expands the concept of accessibility as a device to equalize not only the dance stage but also the stage of the community.

Even in the moment of becoming part of a wonderful community, we must be aware of the existence of others beyond the same "us," and consider the context in which other members will experience it.

The democratic principles of dance are also the democratic principles of a society.

Accessibility is not a specific set of formats that govern many areas of life, nor is it an ideology.

Increasing accessibility is a practice that involves so many different cases and entities that it is difficult for a set of rules to serve as a goal for systematic logic or ideology.

Rather, it's the opposite.

Accessibility is the anchor that holds us together when we become captivated by some overwhelming ideology, when we close ourselves off from other members of the world and the various contexts that exist, and when we drift away into a narcissistic (or group-oriented) 'ecstasy'.

_"Democracy of Dance," p. 299

Completely equal and extremely discriminatory… … .

Discrimination and equality, which appear in the book's title, may have become superficial and trite terms used in Korean society today.

Nevertheless, Kim Won-young's reflections on the body, which have continued throughout the history of dance, are enough to re-emerge the flat equality confined by law and institutions as a stage for fierce life.

We will hone our art to respect the equality of power while paying attention to the discriminatory power of specific faces.

When we do, we become part of a larger world, a community of dignity and wonder where no one is discriminated against.

My grandmother and mother worried about the countless strange and suspicious looks they would receive from a child crawling on the floor with a bulging chest about 30 years ago.

The 2020s were different.

Some gazes remain the same, but bodies that have slightly changed their gazes have been empowered by those slight gazes and have changed more quickly, and those changed bodies are radically changing more gazes.

Those who take responsibility for the bodies entrusted to them and strive to dance well have expanded the meaning of good dance. Within this expanded standard of good dance, people who dance even better have emerged, and these people are reconstructing the values of our time about what good dance is.

If we assert our rights, love willingly, and dance to our hearts' content, our lives will not be ruined.

Therefore, the only task before us is to become fully equal and extremely discriminatory beings.

_「Becoming a Dancer, pp. 342-343

Is 'equality of opportunity for beauty' available to everyone?

A lawyer turned dancer pleads for her body

Kim Won-young, known to readers as a lawyer and author of 『A Defense for the Disqualified』 and 『Becoming a Cyborg』 (co-authored).

In the former, there is a heated debate on the legal and social rights of minorities, and in the latter, the bodies of the disabled.

He has been thinking about another identity created through the combination of technology, and this time he has returned with a new question.

Is ‘equal opportunity to be beautiful’ allowed to those with so-called ‘abnormal bodies’?

Even as minorities strive to affirm their dignity and enshrine it in law and institutions, they cannot avoid one remaining question:

'Can I be an attractive being in and of myself (without relying on law, morality, education, or human rights awareness)?'

He confesses.

Although he has criticized discrimination against the disabled and advocated for their equality as a political entity, he has not been able to affirm his own body for a long time.

I was secretly amazed by the “efficiency of the body without disabilities” and thought that the “efficient, fast, and balanced bodies of non-disabled people were beautiful.”

But about 10 years ago, when he got on stage and started moving his body, Kim Won-young began to awaken to “the experience of becoming the most vivid version of himself” and the sense of “existing as himself.”

After realizing the 'power' within his own body through the process of revealing it rather than hiding it, he no longer disguised himself as a non-disabled person.

In the realm of dance, where physical presence is more crucial than in any other art form, what kind of experiences has Kim Won-young, who has a disability, endured? Kim Won-young, who left her life as a lawyer, where her body could be hidden, to become a dancer, revealing her ample chest and slender legs.

His body is the place where fiery thoughts begin.

What exactly is beauty? Have "abnormal" bodies ever graced the stage throughout history? How did they respond to the gaze of their contemporaries, and what did they desire? What kind of stage presence are contemporary disabled dancers creating? Why is accessibility to art, including dance, important not only for people with disabilities but also for people without disabilities?

"Completely Equal and Extremely Discriminatory" is a record of Kim Won-young's exploration of the relationship between discrimination and equality, restoring the presence of forgotten others on stage through personal experiences and the history of dance.

Beginning with a look at the emergence of "unusual" bodies in the history of dance, the film vividly addresses the voices of domestic and international disabled dance troupes and dance teams in the late 20th century, calling upon others from both the Eastern and Western dance worlds, such as Choi Seung-hee and Nijinsky, and further creating their own unique styles.

This book, which examines the order engraved in the body and the scenes of overturning that order, focusing on asymmetrical power relations such as normal and abnormal, majority and minority, East and West, will propose a bold imagination for an equal stage (community) created by different bodies.

It is thanks to witnessing that not only the order engraved in our bodies, but also that sometimes just slightly twisting that order or creating a new order can open a stage for hospitality.

Above all, this book, "A Defense for the Body," reminds us that, in moving toward a world beyond the familiar order, we must ultimately pay attention to the possibilities of specific bodies.

‘Trust in oneself’ is impossible without ‘trust in one’s body,’ and the relationship one has with one’s own body becomes the basis of one’s relationship with the community.

If I continue to make conscious efforts to protect, guard, and hide this body from the gaze of others, violence, and physical accidents without being able to feel and experience the world with my body itself, it will be difficult for me to reach the limit of my body's (=myself's) potential capacity within the situation I am in.

(...) to the point where I forget that I am the 'source' from which my body operates.

The experience of losing ‘me’ and allowing the ‘body’ to become the most vivid version of me.

A boy with a bulging chest who can crawl on the floor but cannot walk has no idea how far his body can move.

I don't know what my body can and can't do.

_「On a Tightrope」, pp. 32-33

From freak show to retard dance,

Even today, we meet dancers with disabilities.

A History of 'Strange' Bodies that Open the Stage for Equality

Can you picture a disabled body dancing on stage? Whether you picture a ballerina or a K-pop dancer, it's likely not a disabled person.

What about the history of dance? Has there ever been a time when sick bodies, "strange" bodies, appeared? Kim Won-young focuses on the freak shows of the modern exhibition culture of the 19th and early 20th centuries as a space where such bodies were revealed.

In the heart of 19th-century imperialism, curiosity about exotic civilizations in the periphery grew, and 'people' quickly delivered along with flora and fauna from distant lands began to appear as exhibits in commercialized 'freak shows.'

Freaks are usually non-European immigrants, people with disabilities, and people with unusual bodies, but Kim Won-young's perspective on freak shows is somewhat complicated.

While freak shows are clearly sites of violence and exploitation with a history of racial and ableist discrimination, they are also places where socially excluded bodies can engage professionally and influence the public.

While maintaining a critical attitude towards the context in which the freak show was held, he wants to remember the courage of the freaks who faced contempt and exclusion, and the pride of not giving up self-respect amidst all that.

Meanwhile, in the tradition of Korean dance, the most representative dance performed by people with disabilities is the 'Byeongsin Dance'.

How did the "Byeongsin Dance" appeal to the author, who has a "sick body"? The idea that this dance degrades and mocks people with disabilities has long been a concern, and disability groups even raised criticism of the dance in the 1980s.

Of course, opinions are divided, ranging from the view that the disabled dance is a dance of 'human liberation' to the view that the common people objectify the disabled, who are weaker than themselves, as a means of liberation.

Rather than jumping to conclusions about the dance of the disabled, the author examines various perspectives and questions the existence of the subject performing this dance.

The Miryang Baekjungnori performers that I have seen on video sometimes acted exaggeratedly and comically at certain moments, but for the most part, they realistically imitated the body movements down to the smallest detail.

But they didn't seem like real 'idiots' who danced in a spirited manner, liberated from the world's authority, order, and people's gaze ('stares').

They were 'handicapped performers' who meticulously imitated the disabled.

What I found in their acting and dancing were not abstract, expressive gestures that overturned the hierarchical, physical, and cultural order and symbolized human liberation and harmony.

It was a daily gesture that the senior I spoke to in the break room had been making, and it was an image that was reproduced through effective imitation.

(...) If there is no 'disabled person' who dances the 'disabled dance' for whatever reason, I cannot accept the interpretation that this dance is not a dance that simply mocks disability, but rather a dance that breaks free from oppression, reaches enlightenment together, and creates a place for liberation and harmony.

_「Dance of the Sick Bodies」, pp. 118-120

However, as in the example above, 'abnormal' bodies were not only confined to the gaze and constraints of normal people.

In the early 20th century, Korean dancer Choi Seung-hee and Japanese actress Kawakami Sadayako were consumed as colonial and Oriental other, but they sought to confront the dominant gaze surrounding the stage and redefine their ability to dance on their own.

Entering the latter half of the 20th century, we can encounter a growing number of 'other bodies' both domestically and internationally, who create a stir by focusing on the power they possess.

Examples include Kim Man-ri, a Zainichi Korean performer who crawled on stage in a leotard in Kyoto, Japan in the 1980s, asserting the radicalism of uncivilized bodies; the British Candoco Dance Company, which did not hide the physical characteristics of each disabled person—protruding rib cages, amputated legs, etc.—but brought them to the forefront on stage; the Bremen Theater Dance Company in Germany, which sought to reach the experiences of other bodies through choreography that imitated each other's movements; and actor Baek Woo-ram ('Theatre Lover'), who embraced the involuntary movements of his body in his own way rather than controlling them.

Sometimes, they find the rhythm of their words while being 'stuck for words' on stage, and by dancing with both arms as best they can without legs, they easily overcome the prejudice that disability is a flaw that prevents them from dancing.

I accepted that I couldn't dance all the dances, but I found my own unique realm by struggling with my 'helpless body'.

In the process of passing through this diverse world of bodies, the power relations between normal and abnormal are reversed, and readers can witness moments of beauty and wonder in which different bodies exist in their own ways.

When we create a strange and creatively unexpected moment in front of the 'gaze' that captures, trades, mocks, exploits, hates, sympathizes, and desires, that is, when we discover ourselves as a body that cannot possibly be captured, traded, mocked, exploited, hated, pitied, or desired, we all open the door to a world we have never imagined before.

The person looking and the person being looked at enter into a completely different relationship than before.

_「Inside and Outside the Gaze」, p. 97

A Question for a Community of Wonder Where Other Bodies Dance Together

How can 'abnormal bodies' be treated equally?

Our discrimination is more beautiful than your equality.

Let's go back to the original question.

Are "disabled bodies" and non-disabled bodies equal? Are these bodies given equal opportunities to be beautiful? Kim Won-young emphasizes that we are all equal in that we possess "power."

However, power is not synonymous with ability.

Power is the foundation of ability, but it does not remain within one's limitations; it is also the driving force that changes the world's standards of ability.

Thus, although we are in a highly discriminatory relationship because each of us has different abilities, we can achieve complete equality by respecting and trusting each other's strengths.

For example, just because a ballerina doesn't dance ballet in front of Kim Won-young, it doesn't mean that he and the ballerina are equal.

With her ability to dance ballet well, the ballerina can suggest ways to access a world unknown to Kim Won-young.

Meanwhile, Kim Won-young cannot tightrope walk, but he has a "differentiating ability" to rhythmically crawl under a rubber band, and he can invite ballerinas to his performances to suggest other body-becomings (this move is also part of the choreography of "Reality Principle" performed by Kim Won-young).

His 'creeping movements' are the accumulation of a long period of struggle with his body, having been told since childhood, "Don't crawl, don't bulge," and those bodies are connected to the bodies of the people who took care of him, the individuals he met, learned with, and performed on stage with.

Kim Won-young's unique experience leaves a distinctive power in his body, and that power is the root that creates a different world.

For Kim Won-young, dancing is not just a matter of personal pleasure.

The existence of a dancer with a disability is political in itself, as it transcends the norms expected of their bodies, and communal, as it presupposes the existence of others.

Since a community cannot be established without the concept of 'we', it is inevitable that some beings will be excluded. He proposes 'accessibility', a principle of dance, as a new ethics for the community.

As discussed in detail in Part 2, “Opening a Closed World,” accessibility in the field of dance means installing barrier-free devices in the audience and attempts to enable various movements on stage. However, he expands the concept of accessibility as a device to equalize not only the dance stage but also the stage of the community.

Even in the moment of becoming part of a wonderful community, we must be aware of the existence of others beyond the same "us," and consider the context in which other members will experience it.

The democratic principles of dance are also the democratic principles of a society.

Accessibility is not a specific set of formats that govern many areas of life, nor is it an ideology.

Increasing accessibility is a practice that involves so many different cases and entities that it is difficult for a set of rules to serve as a goal for systematic logic or ideology.

Rather, it's the opposite.

Accessibility is the anchor that holds us together when we become captivated by some overwhelming ideology, when we close ourselves off from other members of the world and the various contexts that exist, and when we drift away into a narcissistic (or group-oriented) 'ecstasy'.

_"Democracy of Dance," p. 299

Completely equal and extremely discriminatory… … .

Discrimination and equality, which appear in the book's title, may have become superficial and trite terms used in Korean society today.

Nevertheless, Kim Won-young's reflections on the body, which have continued throughout the history of dance, are enough to re-emerge the flat equality confined by law and institutions as a stage for fierce life.

We will hone our art to respect the equality of power while paying attention to the discriminatory power of specific faces.

When we do, we become part of a larger world, a community of dignity and wonder where no one is discriminated against.

My grandmother and mother worried about the countless strange and suspicious looks they would receive from a child crawling on the floor with a bulging chest about 30 years ago.

The 2020s were different.

Some gazes remain the same, but bodies that have slightly changed their gazes have been empowered by those slight gazes and have changed more quickly, and those changed bodies are radically changing more gazes.

Those who take responsibility for the bodies entrusted to them and strive to dance well have expanded the meaning of good dance. Within this expanded standard of good dance, people who dance even better have emerged, and these people are reconstructing the values of our time about what good dance is.

If we assert our rights, love willingly, and dance to our hearts' content, our lives will not be ruined.

Therefore, the only task before us is to become fully equal and extremely discriminatory beings.

_「Becoming a Dancer, pp. 342-343

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 1, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 360 pages | 576g | 140*220*22mm

- ISBN13: 9791141606459

- ISBN10: 1141606453

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)