Your dreams are not accidental

|

Description

Book Introduction

This book provides a neuroscientific explanation of the meaning and origin of dreams. It answers core questions such as what dreams are, where they come from, what they mean, and why we dream, based on neuroscientific ideas and the latest findings. It contains information that anyone would be curious about dreams, from the definition of dreams and the process of conceptualizing human dreams to forgotten pioneers in dream research, their connection to sleep, the content and types of dreams, and the functions and possibilities of dreams. In particular, we will examine the functions and possibilities of dreams, focusing on the dream research theory called 'NEXTUP', and introduce methods of utilizing dreams to bring out inner potential and connect it to reality. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommended Article: Time to become an artist who creates dreams and the future.

Introduction Your Brain Knows Your Dreams

Chapter 1: What is a Dream?

Dreams, a Fake Reality That Feels Real | How Do Children Perceive Dreams? | The Uncertainty of Dreams and Waking | What Can Be Considered a 'Dream'?

Chapter 2: Early Explorers of the Dream World

Freud's Arrogance | Dream Researchers Before Freud | Alfred Maury, Who Accessed the Dream World on His Own | Carl Schener, Who Discovered the Symbolism of Dreams | Saint-Denis, a Pioneer in Lucid Dream Research | Calkins, Who Laid the Foundation for Statistical Dream Research | De Sanctis, Who Developed a Multifaceted Approach to Dream Research

Chapter 3: Did Freud Uncover the Secret of Dreams?

Dreams are the guardians of sleep | Jung and the alternative to the clinical conception of dreams | Freud is overrated | Experimental psychologists who challenged Freud's theories

Chapter 4: The Birth of a New Dream Science

REM, rapid, sudden eye movements | REM sleep cycle | Dreams during the night | Talking about dream content

Chapter 5: Is sleep just a solution to drowsiness?

Sleep Management Functions | Main Functions of Sleep | Sleep and Memory Evolution | When Sleep Doesn't Work Properly

Chapter 6 “Do Dogs Dream?”

Do animals dream? | Do babies dream? | People who don't dream | The brain that shows a dreamlike state

Chapter 7 “Why Do We Dream?”

How Does the Brain Create Dreams? | What is the Function of Dreams? 1 | What is the Function of Dreams? 2 | Why Do We Dream?

Chapter 8: Network Exploration for Understanding Possibilities

Exploring the Next-Up Model and Weak Correlations | Next-Up and the Strangeness of Dreams | The Meaning of Understanding Possibilities | Assigning Meaning to Next-Up and Dreams | Next-Up and Each Stage of Dreams | Next-Up and the DMN | Next-Up and the Function of Dreams in Each Sleep Stage | Next-Up and Insomnia | Could Bird Dreams Have a Next-Up Function?

Chapter 9: The Innumerable Contents of a Dream

Hall and Van de Castle's Dream Scoring System | Next Up and Formal Characteristics of Dreams | Formal Properties of Dreams in Each Sleep Stage

Chapter 10: What Do We Dream?

Everyday Dreams | Typical Dreams | Recurring Dreams | Nightmares | Sexual Dreams | Dream Content and Next Up

Chapter 11: Dreams and Inner Creativity

Creativity as a Problem-Solving Ability | Dream Creativity and the Multi-Framework of Thought | Capturing Creativity in Dreams

Chapter 12 Dream Work

Clinical Uses of Dreams | Personal Dream Work | Finding Meaning in a Series of Dreams | Next Up, Insight, and the Source of Dreams in Reality

Chapter 13: Things We Encounter at Night

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) nightmares | Idiopathic nightmares | Idiopathic nightmares and the next step | Nightmares and image rehearsal therapy | Sleep paralysis | REM sleep behavior disorder | Narcolepsy | Sleepwalking | Vast dreams

Chapter 14: Awake Mind, Sleeping Brain

What is and isn't a lucid dream? Left, right, left, right. When the brain is lucid, how to induce a lucid dream. Wait, turn, and keep dreaming. Interacting with characters in lucid dreams.

Chapter 15: Telepathy and Precognitive Dreams

Dreams and Telepathy | Experimental Investigation of Supernatural Dreams | Precognitive Dreams: Coincidences Created by the Brain's Unconscious

What We Know and Don't Know About Late Dreams

The Peak and Fall of Dream Research | Another Thought on Next Up and the Function of Dreams | What's Next? | The Mystery and Magic of Dreams

Acknowledgements

Appendix: How Dreams Work, Revealed by Nextup

Further Reading

References

Introduction Your Brain Knows Your Dreams

Chapter 1: What is a Dream?

Dreams, a Fake Reality That Feels Real | How Do Children Perceive Dreams? | The Uncertainty of Dreams and Waking | What Can Be Considered a 'Dream'?

Chapter 2: Early Explorers of the Dream World

Freud's Arrogance | Dream Researchers Before Freud | Alfred Maury, Who Accessed the Dream World on His Own | Carl Schener, Who Discovered the Symbolism of Dreams | Saint-Denis, a Pioneer in Lucid Dream Research | Calkins, Who Laid the Foundation for Statistical Dream Research | De Sanctis, Who Developed a Multifaceted Approach to Dream Research

Chapter 3: Did Freud Uncover the Secret of Dreams?

Dreams are the guardians of sleep | Jung and the alternative to the clinical conception of dreams | Freud is overrated | Experimental psychologists who challenged Freud's theories

Chapter 4: The Birth of a New Dream Science

REM, rapid, sudden eye movements | REM sleep cycle | Dreams during the night | Talking about dream content

Chapter 5: Is sleep just a solution to drowsiness?

Sleep Management Functions | Main Functions of Sleep | Sleep and Memory Evolution | When Sleep Doesn't Work Properly

Chapter 6 “Do Dogs Dream?”

Do animals dream? | Do babies dream? | People who don't dream | The brain that shows a dreamlike state

Chapter 7 “Why Do We Dream?”

How Does the Brain Create Dreams? | What is the Function of Dreams? 1 | What is the Function of Dreams? 2 | Why Do We Dream?

Chapter 8: Network Exploration for Understanding Possibilities

Exploring the Next-Up Model and Weak Correlations | Next-Up and the Strangeness of Dreams | The Meaning of Understanding Possibilities | Assigning Meaning to Next-Up and Dreams | Next-Up and Each Stage of Dreams | Next-Up and the DMN | Next-Up and the Function of Dreams in Each Sleep Stage | Next-Up and Insomnia | Could Bird Dreams Have a Next-Up Function?

Chapter 9: The Innumerable Contents of a Dream

Hall and Van de Castle's Dream Scoring System | Next Up and Formal Characteristics of Dreams | Formal Properties of Dreams in Each Sleep Stage

Chapter 10: What Do We Dream?

Everyday Dreams | Typical Dreams | Recurring Dreams | Nightmares | Sexual Dreams | Dream Content and Next Up

Chapter 11: Dreams and Inner Creativity

Creativity as a Problem-Solving Ability | Dream Creativity and the Multi-Framework of Thought | Capturing Creativity in Dreams

Chapter 12 Dream Work

Clinical Uses of Dreams | Personal Dream Work | Finding Meaning in a Series of Dreams | Next Up, Insight, and the Source of Dreams in Reality

Chapter 13: Things We Encounter at Night

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) nightmares | Idiopathic nightmares | Idiopathic nightmares and the next step | Nightmares and image rehearsal therapy | Sleep paralysis | REM sleep behavior disorder | Narcolepsy | Sleepwalking | Vast dreams

Chapter 14: Awake Mind, Sleeping Brain

What is and isn't a lucid dream? Left, right, left, right. When the brain is lucid, how to induce a lucid dream. Wait, turn, and keep dreaming. Interacting with characters in lucid dreams.

Chapter 15: Telepathy and Precognitive Dreams

Dreams and Telepathy | Experimental Investigation of Supernatural Dreams | Precognitive Dreams: Coincidences Created by the Brain's Unconscious

What We Know and Don't Know About Late Dreams

The Peak and Fall of Dream Research | Another Thought on Next Up and the Function of Dreams | What's Next? | The Mystery and Magic of Dreams

Acknowledgements

Appendix: How Dreams Work, Revealed by Nextup

Further Reading

References

Detailed image

Into the book

This book proposes a new and innovative model for explaining why we dream, drawing on remarkable neuroscientific ideas and cutting-edge findings from research on sleep and dreams.

We will call this NEXTUP (Network Exploration to Understand Possibilities).

Simply put, it is a new theory that studies the meaning and possibilities of dreams.

We delve into how NextUp works, uncovering why the human brain needs dreams and offering new answers to four fundamental questions: what are dreams, where do they come from, what do dreams mean, and why do we dream?

--- p.10, from the "Preface"

There are many possible explanations for what happens in the brain when we dream.

In this book, we will explore all these possible explanations and see where they lead us.

There is no right answer, and explanations are not exclusive.

Sometimes, if you look at it a little more flexibly, it can all be reasonable.

But the most interesting explanation, both intellectually and scientifically, is the approach mentioned last, that dreams are memory processing.

--- p.27, from “Chapter 1: What is a Dream”

Freud's ideas and theories were certainly revolutionary, and The Interpretation of Dreams had a profound influence on dream research.

However, Freud's disdain and selective portrayal of dream theory and research that preceded his masterpiece obscured the valuable contributions of dozens of researchers before him, and scientific dream research virtually lost its momentum for the next fifty years.

Dream research before Freud was gradually relegated to the trash can and eventually forgotten by people.

So, we begin our journey into the science of dreams with the pioneers of dream research, some of whom have been forgotten.

It is the first step to reviving the achievements of those who deserve recognition.

--- p.36, from “Chapter 2: Early Explorers of the Dream World”

Do all of these dream theories align with Freud's assertions that "dreams are wish fulfillments" or "guardians of sleep"? Numerous dream studies have reached the simple conclusion that there is little empirical evidence to support Freud's claims of dream function.

Moreover, most scientists studying sleep and dreams have long since abandoned Freud's conceptualization of dreaming in favor of a streamlined, experimental model rooted in modern clinical and neuroscience.

But that doesn't mean that modern dream researchers have abandoned the notion that dreams have personal meaning, that they reflect the dreamer's waking anxieties, that they reference old memories, or that dreamwork is clinically useful.

All of these concepts have been and will continue to be innovative research topics.

It has little to do with Freud's dream theory itself.

--- p.58, from “Chapter 3: Did Freud Reveal the Secret of Dreams?”

When we compared dream reports obtained by waking participants during REM sleep with reports obtained by waking them during non-REM sleep, a surprising result emerged.

When participants were awakened from non-REM sleep, only 7 percent reported a "coherent and detailed description of the dream."

However, when awakened during REM sleep, 80 percent of the participants—more than 10 times more—reported consistent dreaming.

Dreams were no longer mystical mental phenomena emerging from somewhere hidden deep within the mind.

In an instant, the dream became a 'biological function'.

--- p.68, from “Chapter 4: The Birth of a New Dream Science”

Sleep helps solidify recently formed memories and prevents them from being forgotten or disturbed, but its functions are much more extensive.

The term 'memory evolution' draws attention to the numerous functions of sleep, as well as the fact that memory continually changes in various ways throughout life.

--- p.95, from “Chapter 5: Is sleep just a solution to drowsiness?”

As you can see, we've run into a much trickier problem than whether dogs dream.

The question is whether animals other than humans have consciousness.

Bob often surprises his students by saying that there is no scientific evidence that humans are conscious.

It's true.

Philosopher David Chalmers points out that “we think we know conscious experience very well, but in fact nothing is more difficult to explain.”

--- p.110, from Chapter 6, “Do Dogs Dream?”

In 2016, Levonsuo and his colleagues advanced the theory that dreams are alternative social simulations, arguing that the function of dreams is to simulate and reinforce "social skills, relationships, interactions, and networks relevant to the real world." Like the TST model, the social simulation theory of dreams argues that dream simulations enhanced our ancestors' survival and adaptability.

--- p.133, from Chapter 7, “Why Do We Dream?”

When we dream, our brain explores weakly connected networks to understand possibilities.

The brain explores more broadly than it does when awake, investigates less obvious connections, and finds hidden treasures in places it would never look while awake.

During bright daylight, when the brain is primarily focused on processing newly acquired sensations and the neurotransmitters in the brain are optimized for processing information in the here and now, it is difficult to determine whether newly identified associations are useful or "correct."

But that's okay.

There's no need to understand why the brain chooses these associations.

We don't even need to know whether the associations used to build our dreams are useful or not.

You don't even need to remember your dreams.

Because all the important work was done while we were sleeping.

While we dream, our brain discovers, explores, and evaluates associations.

And if some of these associations are deemed truly novel, creative, and potentially useful, the brain strengthens them and stores them for later use.

--- p.150, from “Chapter 8 Network Exploration for Understanding Possibilities”

Unlike classical music, there is no recapitulation at the end of a dream.

Like a good novel, the denouement is not connected to the beginning.

This pattern of dreams is valid.

Dreams rarely come to a clean conclusion.

The most common ending to a dream report is “And then I woke up from the dream.”

The dreaming brain doesn't compose the entire storyline.

In fact, because of the decline in norepinephrine we discussed in Chapter 8, NextUp cannot sustain a single plot narrative for long.

Instead, NextUp works by observing the "principle of proximity," weaving together a series of memories and network explorations.

Much like a cocktail party conversation, we move from topic to topic in a constantly unfolding narrative, always finding new, potentially useful connections.

--- p.186, from “Chapter 9: The Innumerable Contents of a Dream”

But rather than bringing in the entire episodic memory from the previous day's events and inserting it, the brain only brings in bits and pieces: objects, settings, characters, impressions, fleeting thoughts, and brief conversations.

Some of these daytime remnants combine with details from older, weakly related memories to form the details that make up a personal dream narrative.

--- p.220, from “Chapter 10: What Do We Dream of?”

True creativity, as discovered in dreams, arises from creative exploration of associated neural networks, where the brain identifies weak connections that are crucial for problem solving.

Whether this process can be considered true creativity becomes a problem when defining dream creativity.

Robert Franken, in his book Human Motivation, defines creativity as “the tendency to generate and recognize ideas, alternatives, and possibilities that are useful for solving problems, communicating with others, and entertaining ourselves and others.”

--- p.236, from “Chapter 11 Dreams and Inner Creativity”

But we do not see dreams as a mechanism that evolved simply to be interpreted.

The first reason this idea doesn't make sense is because we remember so few of the dreams we have each night.

The second reason is that among the dreams we 'remember', there are very few that can be interpreted by anyone, let alone so-called experts.

Therefore, it is important to distinguish between the biological and adaptive functions of dreams that occur 'vividly' while the dream unfolds and the uses of dreams, such as interpretation, creativity, or simple enjoyment, that we 'select' for the purpose of understanding the dream we remember after waking.

--- p.245, from “Chapter 12 Dream Work”

But dreams, and by extension the neurobiology of next-up, are too complex to be simply judged as success or failure.

Between the extremes of success and failure, there is a broad middle ground where sleep-dependent memory evolution occurs intermittently and with varying effects.

For example, 90 percent of people who develop PTSD after being exposed to trauma report nightmares that are similar in many ways to the traumatic event itself, but only half of the nightmares replay the traumatic memory.

Instead, post-traumatic nightmares may distort and reveal traumatic elements, metaphorically present the traumatic event, or relive the same distressing emotions—fear, sadness, helplessness—that were experienced at the time of the trauma without directly mentioning the actual traumatic event.

--- p.267, from “Chapter 13 Things We Encounter at Night”

Many people confuse the concepts of lucid dreaming and dream control.

But these two are different.

Although two experiences can and do occur simultaneously, being aware that you are dreaming may not allow you to change the direction of the dream, nor may you want to.

Conversely, you can intentionally change things in your dreams in ways that would be impossible in the real world, even if you don't realize you're dreaming.

Moreover, the term ‘dream control’ is inappropriate.

Lucid dreamers can consciously direct their actions in their dreams, but most can only 'influence' how the dream unfolds.

--- p.293, from “Chapter 14: Awake Mind, Sleeping Brain”

But another possibility is that the vague nature of dream memory, coupled with the associative nature of dreams (“I think there was something to do with cats…”), allows us to retrospectively recall a dream as being related to a particular topic, such as the death of a parent, even though they have nothing in common (“I felt really sad, like I lost something…”).

We will call this NEXTUP (Network Exploration to Understand Possibilities).

Simply put, it is a new theory that studies the meaning and possibilities of dreams.

We delve into how NextUp works, uncovering why the human brain needs dreams and offering new answers to four fundamental questions: what are dreams, where do they come from, what do dreams mean, and why do we dream?

--- p.10, from the "Preface"

There are many possible explanations for what happens in the brain when we dream.

In this book, we will explore all these possible explanations and see where they lead us.

There is no right answer, and explanations are not exclusive.

Sometimes, if you look at it a little more flexibly, it can all be reasonable.

But the most interesting explanation, both intellectually and scientifically, is the approach mentioned last, that dreams are memory processing.

--- p.27, from “Chapter 1: What is a Dream”

Freud's ideas and theories were certainly revolutionary, and The Interpretation of Dreams had a profound influence on dream research.

However, Freud's disdain and selective portrayal of dream theory and research that preceded his masterpiece obscured the valuable contributions of dozens of researchers before him, and scientific dream research virtually lost its momentum for the next fifty years.

Dream research before Freud was gradually relegated to the trash can and eventually forgotten by people.

So, we begin our journey into the science of dreams with the pioneers of dream research, some of whom have been forgotten.

It is the first step to reviving the achievements of those who deserve recognition.

--- p.36, from “Chapter 2: Early Explorers of the Dream World”

Do all of these dream theories align with Freud's assertions that "dreams are wish fulfillments" or "guardians of sleep"? Numerous dream studies have reached the simple conclusion that there is little empirical evidence to support Freud's claims of dream function.

Moreover, most scientists studying sleep and dreams have long since abandoned Freud's conceptualization of dreaming in favor of a streamlined, experimental model rooted in modern clinical and neuroscience.

But that doesn't mean that modern dream researchers have abandoned the notion that dreams have personal meaning, that they reflect the dreamer's waking anxieties, that they reference old memories, or that dreamwork is clinically useful.

All of these concepts have been and will continue to be innovative research topics.

It has little to do with Freud's dream theory itself.

--- p.58, from “Chapter 3: Did Freud Reveal the Secret of Dreams?”

When we compared dream reports obtained by waking participants during REM sleep with reports obtained by waking them during non-REM sleep, a surprising result emerged.

When participants were awakened from non-REM sleep, only 7 percent reported a "coherent and detailed description of the dream."

However, when awakened during REM sleep, 80 percent of the participants—more than 10 times more—reported consistent dreaming.

Dreams were no longer mystical mental phenomena emerging from somewhere hidden deep within the mind.

In an instant, the dream became a 'biological function'.

--- p.68, from “Chapter 4: The Birth of a New Dream Science”

Sleep helps solidify recently formed memories and prevents them from being forgotten or disturbed, but its functions are much more extensive.

The term 'memory evolution' draws attention to the numerous functions of sleep, as well as the fact that memory continually changes in various ways throughout life.

--- p.95, from “Chapter 5: Is sleep just a solution to drowsiness?”

As you can see, we've run into a much trickier problem than whether dogs dream.

The question is whether animals other than humans have consciousness.

Bob often surprises his students by saying that there is no scientific evidence that humans are conscious.

It's true.

Philosopher David Chalmers points out that “we think we know conscious experience very well, but in fact nothing is more difficult to explain.”

--- p.110, from Chapter 6, “Do Dogs Dream?”

In 2016, Levonsuo and his colleagues advanced the theory that dreams are alternative social simulations, arguing that the function of dreams is to simulate and reinforce "social skills, relationships, interactions, and networks relevant to the real world." Like the TST model, the social simulation theory of dreams argues that dream simulations enhanced our ancestors' survival and adaptability.

--- p.133, from Chapter 7, “Why Do We Dream?”

When we dream, our brain explores weakly connected networks to understand possibilities.

The brain explores more broadly than it does when awake, investigates less obvious connections, and finds hidden treasures in places it would never look while awake.

During bright daylight, when the brain is primarily focused on processing newly acquired sensations and the neurotransmitters in the brain are optimized for processing information in the here and now, it is difficult to determine whether newly identified associations are useful or "correct."

But that's okay.

There's no need to understand why the brain chooses these associations.

We don't even need to know whether the associations used to build our dreams are useful or not.

You don't even need to remember your dreams.

Because all the important work was done while we were sleeping.

While we dream, our brain discovers, explores, and evaluates associations.

And if some of these associations are deemed truly novel, creative, and potentially useful, the brain strengthens them and stores them for later use.

--- p.150, from “Chapter 8 Network Exploration for Understanding Possibilities”

Unlike classical music, there is no recapitulation at the end of a dream.

Like a good novel, the denouement is not connected to the beginning.

This pattern of dreams is valid.

Dreams rarely come to a clean conclusion.

The most common ending to a dream report is “And then I woke up from the dream.”

The dreaming brain doesn't compose the entire storyline.

In fact, because of the decline in norepinephrine we discussed in Chapter 8, NextUp cannot sustain a single plot narrative for long.

Instead, NextUp works by observing the "principle of proximity," weaving together a series of memories and network explorations.

Much like a cocktail party conversation, we move from topic to topic in a constantly unfolding narrative, always finding new, potentially useful connections.

--- p.186, from “Chapter 9: The Innumerable Contents of a Dream”

But rather than bringing in the entire episodic memory from the previous day's events and inserting it, the brain only brings in bits and pieces: objects, settings, characters, impressions, fleeting thoughts, and brief conversations.

Some of these daytime remnants combine with details from older, weakly related memories to form the details that make up a personal dream narrative.

--- p.220, from “Chapter 10: What Do We Dream of?”

True creativity, as discovered in dreams, arises from creative exploration of associated neural networks, where the brain identifies weak connections that are crucial for problem solving.

Whether this process can be considered true creativity becomes a problem when defining dream creativity.

Robert Franken, in his book Human Motivation, defines creativity as “the tendency to generate and recognize ideas, alternatives, and possibilities that are useful for solving problems, communicating with others, and entertaining ourselves and others.”

--- p.236, from “Chapter 11 Dreams and Inner Creativity”

But we do not see dreams as a mechanism that evolved simply to be interpreted.

The first reason this idea doesn't make sense is because we remember so few of the dreams we have each night.

The second reason is that among the dreams we 'remember', there are very few that can be interpreted by anyone, let alone so-called experts.

Therefore, it is important to distinguish between the biological and adaptive functions of dreams that occur 'vividly' while the dream unfolds and the uses of dreams, such as interpretation, creativity, or simple enjoyment, that we 'select' for the purpose of understanding the dream we remember after waking.

--- p.245, from “Chapter 12 Dream Work”

But dreams, and by extension the neurobiology of next-up, are too complex to be simply judged as success or failure.

Between the extremes of success and failure, there is a broad middle ground where sleep-dependent memory evolution occurs intermittently and with varying effects.

For example, 90 percent of people who develop PTSD after being exposed to trauma report nightmares that are similar in many ways to the traumatic event itself, but only half of the nightmares replay the traumatic memory.

Instead, post-traumatic nightmares may distort and reveal traumatic elements, metaphorically present the traumatic event, or relive the same distressing emotions—fear, sadness, helplessness—that were experienced at the time of the trauma without directly mentioning the actual traumatic event.

--- p.267, from “Chapter 13 Things We Encounter at Night”

Many people confuse the concepts of lucid dreaming and dream control.

But these two are different.

Although two experiences can and do occur simultaneously, being aware that you are dreaming may not allow you to change the direction of the dream, nor may you want to.

Conversely, you can intentionally change things in your dreams in ways that would be impossible in the real world, even if you don't realize you're dreaming.

Moreover, the term ‘dream control’ is inappropriate.

Lucid dreamers can consciously direct their actions in their dreams, but most can only 'influence' how the dream unfolds.

--- p.293, from “Chapter 14: Awake Mind, Sleeping Brain”

But another possibility is that the vague nature of dream memory, coupled with the associative nature of dreams (“I think there was something to do with cats…”), allows us to retrospectively recall a dream as being related to a particular topic, such as the death of a parent, even though they have nothing in common (“I felt really sad, like I lost something…”).

--- p.325, from “Chapter 15 Telepathy and Precognitive Dreams”

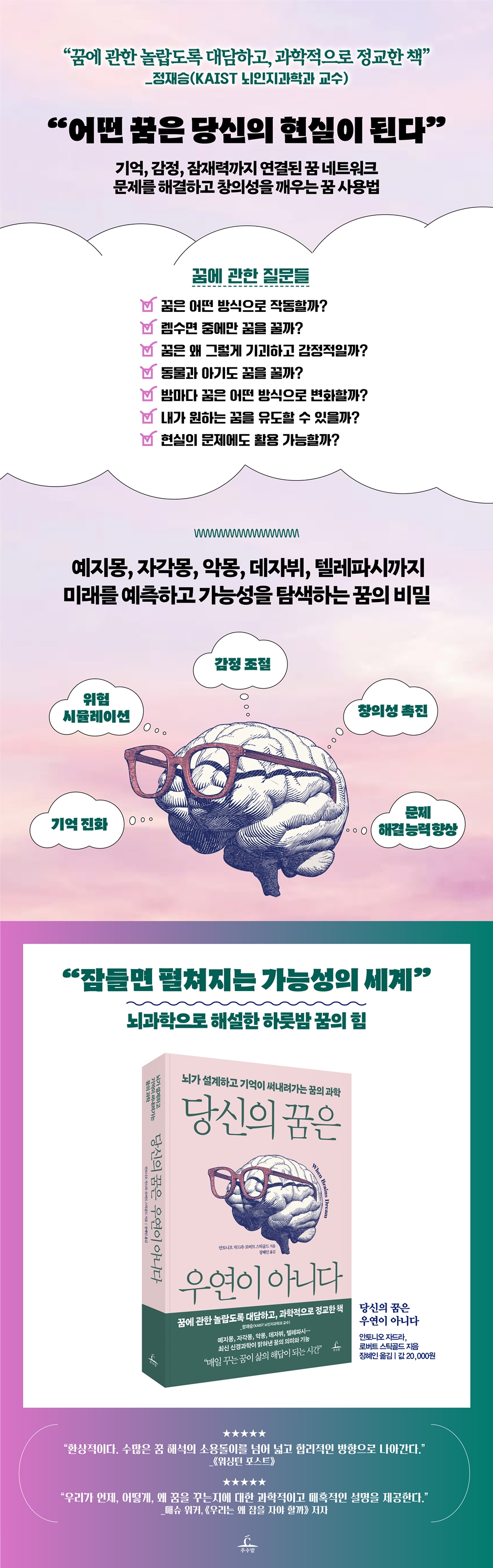

Publisher's Review

“A surprisingly bold and scientifically sophisticated book about dreams.”

_Jeong Jae-seung (Professor, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, KAIST)

“A world of possibilities unfolds when you fall asleep.”

The power of one-night dreams we didn't know about

What do the novel "The Nine Cloud Dreams," the film "Inception," and Salvador Dali's paintings have in common? It's all "dreams."

Dreams are something that anyone can encounter when they fall asleep, but they are a personal realm that only the dreamer can experience.

It's so vivid that it feels like reality, but you only realize it's a dream when you wake up.

This strange and mysterious world has been explored throughout human history and has been the subject of countless works of art and literature.

Because dreams are difficult to define clearly, they have long been considered an unscientific phenomenon and discussed primarily in psychoanalytic terms.

But if you think about it, dreams are scientific.

It deals with events that occur in reality and is based on a cognitive foundation.

This book provides an innovative interpretation of dreams by approaching the meaning and origin of dreams from a neuroscientific perspective.

In this book, world-renowned sleep researchers Antonio Zadra and Robert Stickgold present scientific answers to core questions such as what dreams are, how they work, and why we dream.

Furthermore, we are reinterpreting dreams based on neuroscientific ideas and the latest findings from various studies on sleep and dreams.

In particular, we will explore the functions and possibilities of dreams, focusing on the dream research theory called 'NEXTUP', and even teach you how to utilize dreams to cultivate inner creativity and gain insight.

“What are dreams and why do we dream?”

The Definition of Dreams Explained Through Brain Science

Young children cannot distinguish between dreams and reality, so they mistake dolls for monsters or believe that others can see their dreams as well.

This book talks about the development of children's concept of dreams and speculates that the concept of dreams in humans may have gone through a similar process.

It presents a range of perspectives on what dreams can be, from fragmentary sleep mental activity to epic nocturnal adventures, focusing on the rich and immersive experience of dreaming.

In addition, it introduces early dream researchers who were forgotten and overshadowed by Freud, who was considered a pioneer in dream research, and directly criticizes Freud's dream theory.

We will learn about 'dreams', which we did not know about, through the research of five pioneers of dream research, including Alfred Maury, who came up with the idea that dreams occur instantaneously, Carl Schener, the first to discover the symbolism of dreams, and Saint-Denis, who developed an innovative technique to induce lucid dreams.

“When and How Do We Dream?”

Dreams as Biological Functions and Their Main Functions

Next, we talk about new discoveries in 20th century dream science.

First, let's learn about the discovery of REM sleep, which led us to believe that dreams are a 'biological process'.

We will examine what changes occur in our brain and body during REM sleep, and also study changes in brain, eye, and muscle activity during each sleep stage.

It also explains the characteristics of dreams during REM sleep and corrects the misconception that dreams occur only during REM sleep.

We also introduce a more detailed research method used by dream scientists to collect what participants think in their dreams.

And it speaks of the necessity of 'sleep', which is the passage and process through which we dream.

We explore the key functions of sleep, including helping the body grow, boosting immunity, regulating insulin, and clearing brain waste, as well as evolving memory, forming a sense of self, and enhancing creativity.

In particular, the results of an experiment that examined how typing speed changed before and after sleep revealed how important sleep is for memory processing.

Another important point to consider in understanding sleep and dreams is the question of consciousness. It begins with the question, "Do animals and babies dream?" and discusses the connection between dreams and consciousness.

Furthermore, we will examine the relationship between consciousness and dreams more deeply through examples such as those who do not dream and those in comas.

“A dream that predicts the future and unleashes potential.”

The Infinite Potential of Dreams as Seen Through the 'Next Up' Theory

This book seeks to answer the most fundamental question, "Why do we dream?" through "NextUp," a new theory that explains the biological function and operating principles of dreams.

According to this theory, which stands for "network exploration for understanding possibilities," dreams are "a unique sleep-dependent memory processing process that extracts new knowledge by discovering and strengthening previously unexplored weak associations."

When we dream, our brain explores a network of weakly associated memories to understand a multitude of possibilities.

In an experiment measuring the speed of recognizing words that had different degrees of association with a reference word, participants responded faster to words with strong associations under normal circumstances, but responded faster to words with weak associations when awakened during REM sleep.

Dreams, which operate by first exploring weak connections like this, show us stories that are impossible in reality, predict the future, and explore possibilities.

Based on these next-up principles, it explains why our dreams are bizarre, how dreams change in each stage of sleep, and what function they serve.

Next, we discuss the content of the dream.

First, we will examine the characteristics of dreams and the formal properties of dreams in each sleep stage.

We have compiled interesting properties such as sensory images, such as 'are dreams black and white or color?' and 'what do visually impaired people dream of?', the plot or continuity of dreams, the point of view in dreams, and the type and degree of bizarreness.

Next, let's look at the types of dreams.

From everyday dreams to typical dreams, recurring dreams, nightmares, and sexual dreams, it presents the dreams we have and the characteristics of each dream.

And try to guess where the details of these dreams come from.

“Escape from nightmares and practice lucid dreaming?”

How to Use Dreams to Solve Problems and Awaken Creativity

So what can we achieve with dreams? The authors discuss how dreams stimulate our inner creativity and how we can reap the benefits of this creativity.

We also introduce 'dream incubation techniques', which are techniques you can practice while awake to dream about specific topics or find ways to solve specific problems.

And it guides you on what you can do in your daily life to gain insight from your dreams.

We introduce a personal dream work method that includes recording dreams and asking questions about them as soon as you wake up.

Additionally, we will learn about dream-related disorders such as PTSD nightmares, REM sleep behavior disorder, and narcolepsy, as well as their causes and treatments.

It also explains dreams that are considered strange, such as lucid dreams, telepathic dreams, and precognitive dreams.

It contains interesting information such as what the brain looks like when you are lucid dreaming, how to induce lucid dreams, and how to communicate with characters in lucid dreams.

We also explore the scientific possibility of dreams that allow us to read minds and predict the future through various experimental results.

If we scientifically understand the nature of dreams and discover their possibilities, dreams will no longer be absurd and meaningless phenomena.

It could be a path to coming up with an original idea, or it could be a script that creates a defining scene in your life.

This book will help you discover special ways to utilize your dreams so that they can connect to the possibilities of reality.

_Jeong Jae-seung (Professor, Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, KAIST)

“A world of possibilities unfolds when you fall asleep.”

The power of one-night dreams we didn't know about

What do the novel "The Nine Cloud Dreams," the film "Inception," and Salvador Dali's paintings have in common? It's all "dreams."

Dreams are something that anyone can encounter when they fall asleep, but they are a personal realm that only the dreamer can experience.

It's so vivid that it feels like reality, but you only realize it's a dream when you wake up.

This strange and mysterious world has been explored throughout human history and has been the subject of countless works of art and literature.

Because dreams are difficult to define clearly, they have long been considered an unscientific phenomenon and discussed primarily in psychoanalytic terms.

But if you think about it, dreams are scientific.

It deals with events that occur in reality and is based on a cognitive foundation.

This book provides an innovative interpretation of dreams by approaching the meaning and origin of dreams from a neuroscientific perspective.

In this book, world-renowned sleep researchers Antonio Zadra and Robert Stickgold present scientific answers to core questions such as what dreams are, how they work, and why we dream.

Furthermore, we are reinterpreting dreams based on neuroscientific ideas and the latest findings from various studies on sleep and dreams.

In particular, we will explore the functions and possibilities of dreams, focusing on the dream research theory called 'NEXTUP', and even teach you how to utilize dreams to cultivate inner creativity and gain insight.

“What are dreams and why do we dream?”

The Definition of Dreams Explained Through Brain Science

Young children cannot distinguish between dreams and reality, so they mistake dolls for monsters or believe that others can see their dreams as well.

This book talks about the development of children's concept of dreams and speculates that the concept of dreams in humans may have gone through a similar process.

It presents a range of perspectives on what dreams can be, from fragmentary sleep mental activity to epic nocturnal adventures, focusing on the rich and immersive experience of dreaming.

In addition, it introduces early dream researchers who were forgotten and overshadowed by Freud, who was considered a pioneer in dream research, and directly criticizes Freud's dream theory.

We will learn about 'dreams', which we did not know about, through the research of five pioneers of dream research, including Alfred Maury, who came up with the idea that dreams occur instantaneously, Carl Schener, the first to discover the symbolism of dreams, and Saint-Denis, who developed an innovative technique to induce lucid dreams.

“When and How Do We Dream?”

Dreams as Biological Functions and Their Main Functions

Next, we talk about new discoveries in 20th century dream science.

First, let's learn about the discovery of REM sleep, which led us to believe that dreams are a 'biological process'.

We will examine what changes occur in our brain and body during REM sleep, and also study changes in brain, eye, and muscle activity during each sleep stage.

It also explains the characteristics of dreams during REM sleep and corrects the misconception that dreams occur only during REM sleep.

We also introduce a more detailed research method used by dream scientists to collect what participants think in their dreams.

And it speaks of the necessity of 'sleep', which is the passage and process through which we dream.

We explore the key functions of sleep, including helping the body grow, boosting immunity, regulating insulin, and clearing brain waste, as well as evolving memory, forming a sense of self, and enhancing creativity.

In particular, the results of an experiment that examined how typing speed changed before and after sleep revealed how important sleep is for memory processing.

Another important point to consider in understanding sleep and dreams is the question of consciousness. It begins with the question, "Do animals and babies dream?" and discusses the connection between dreams and consciousness.

Furthermore, we will examine the relationship between consciousness and dreams more deeply through examples such as those who do not dream and those in comas.

“A dream that predicts the future and unleashes potential.”

The Infinite Potential of Dreams as Seen Through the 'Next Up' Theory

This book seeks to answer the most fundamental question, "Why do we dream?" through "NextUp," a new theory that explains the biological function and operating principles of dreams.

According to this theory, which stands for "network exploration for understanding possibilities," dreams are "a unique sleep-dependent memory processing process that extracts new knowledge by discovering and strengthening previously unexplored weak associations."

When we dream, our brain explores a network of weakly associated memories to understand a multitude of possibilities.

In an experiment measuring the speed of recognizing words that had different degrees of association with a reference word, participants responded faster to words with strong associations under normal circumstances, but responded faster to words with weak associations when awakened during REM sleep.

Dreams, which operate by first exploring weak connections like this, show us stories that are impossible in reality, predict the future, and explore possibilities.

Based on these next-up principles, it explains why our dreams are bizarre, how dreams change in each stage of sleep, and what function they serve.

Next, we discuss the content of the dream.

First, we will examine the characteristics of dreams and the formal properties of dreams in each sleep stage.

We have compiled interesting properties such as sensory images, such as 'are dreams black and white or color?' and 'what do visually impaired people dream of?', the plot or continuity of dreams, the point of view in dreams, and the type and degree of bizarreness.

Next, let's look at the types of dreams.

From everyday dreams to typical dreams, recurring dreams, nightmares, and sexual dreams, it presents the dreams we have and the characteristics of each dream.

And try to guess where the details of these dreams come from.

“Escape from nightmares and practice lucid dreaming?”

How to Use Dreams to Solve Problems and Awaken Creativity

So what can we achieve with dreams? The authors discuss how dreams stimulate our inner creativity and how we can reap the benefits of this creativity.

We also introduce 'dream incubation techniques', which are techniques you can practice while awake to dream about specific topics or find ways to solve specific problems.

And it guides you on what you can do in your daily life to gain insight from your dreams.

We introduce a personal dream work method that includes recording dreams and asking questions about them as soon as you wake up.

Additionally, we will learn about dream-related disorders such as PTSD nightmares, REM sleep behavior disorder, and narcolepsy, as well as their causes and treatments.

It also explains dreams that are considered strange, such as lucid dreams, telepathic dreams, and precognitive dreams.

It contains interesting information such as what the brain looks like when you are lucid dreaming, how to induce lucid dreams, and how to communicate with characters in lucid dreams.

We also explore the scientific possibility of dreams that allow us to read minds and predict the future through various experimental results.

If we scientifically understand the nature of dreams and discover their possibilities, dreams will no longer be absurd and meaningless phenomena.

It could be a path to coming up with an original idea, or it could be a script that creates a defining scene in your life.

This book will help you discover special ways to utilize your dreams so that they can connect to the possibilities of reality.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 25, 2023

- Page count, weight, size: 368 pages | 684g | 152*224*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791155402252

- ISBN10: 1155402251

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)