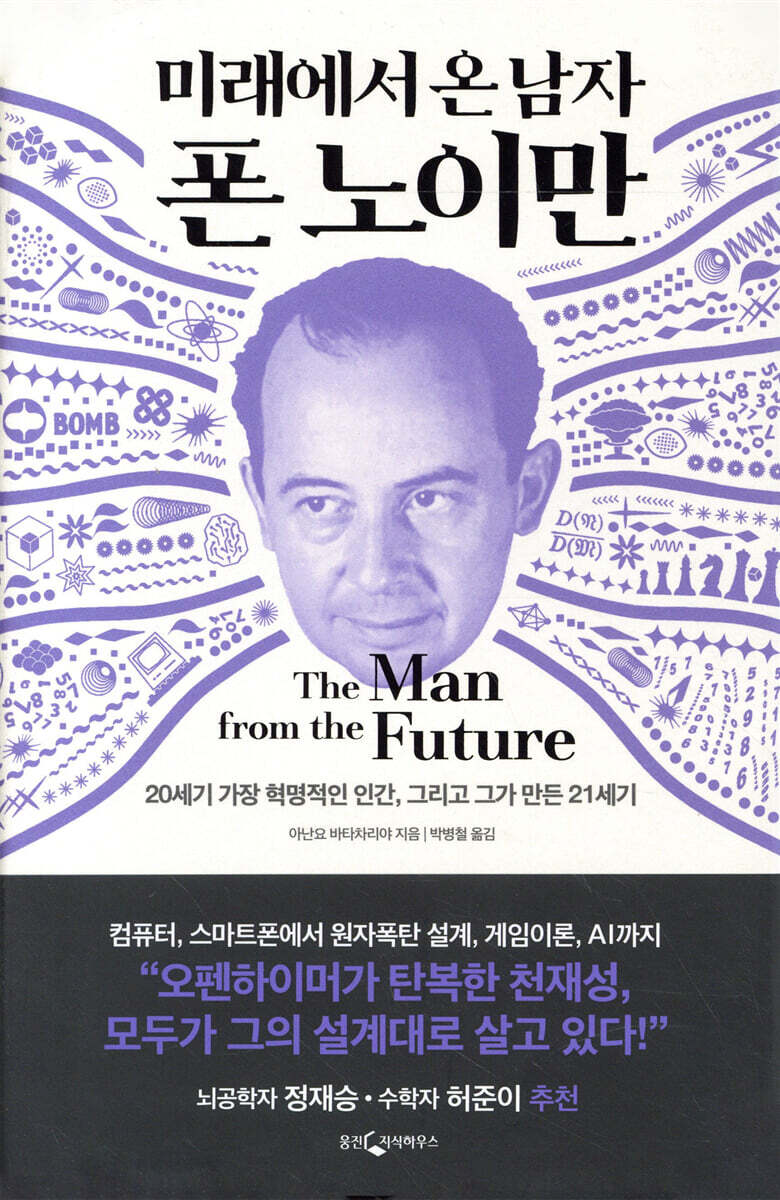

The Man from the Future, Von Neumann

|

Description

Book Introduction

Computers and the 'von Neumann architecture', game theory and quantum mechanics,

From the Manhattan Project and intercontinental ballistic missiles to automata theory and AI. A dazzling biography of an extraordinary genius in the breathtaking history of science in the 20th century. “Our entire life is the history of 20th century science. Now we are living according to von Neumann’s design!” Amazon UK and US rank #1 in science 2022 Financial Times Book of the Year Did you know that the bold ideas that have laid the foundations of 21st-century life—the smartphones and digital computers we use every day, the geopolitics of nuclear war looming over the globe, the rapidly evolving artificial intelligence (AI), and even self-replicating spaceships—all originated in the mind of a genius scientist? That scientist is John von Neumann, one of the most influential scientists in history. Born in Budapest in 1903, he mastered calculus at the age of eight, contributed to the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics, and played a key role in the Manhattan Project and the design of the atomic bomb at the request of Robert Oppenheimer. Not only did he contribute to laying the foundations of Cold War geopolitics and modern economic theory through 'game theory', but he also created the first programmable digital computer, 'EDVAC', making him the 'father of modern computers' and predicting the potential of self-replicating machines. During his time at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, his colleagues called him "the world's fastest brain," beating out Einstein and Gödel, who were considered geniuses of their time. Author Ananyo Bhattacharya re-evaluates the extensive academic achievements and contributions of John von Neumann, a man less well-known historically than Einstein or Richard Feynman, while also vividly portraying the history of 20th-century science through compelling storytelling. Centered around Neumann, the exhibition presents a panorama of intellectual exchange and creativity among the geniuses who shaped the 'belle epoque era of 20th-century science and technology.' |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

· Recommendations · Preface to the Korean edition

Preface by von Neumann, Man More Than Human

Chapter 1: The Mathematical Genius of Budapest: The Secret of the Hungarian Phenomenon

Chapter 2: Beyond Infinity - The Teenage Boy Who Saved Mathematics from Crisis

Chapter 3: Opening the Age of Quantum Mechanics - How Does God Play the Dice Game?

Chapter 4: The Manhattan Project and Nuclear War: An Apocalypse foretelling the destruction of humanity

Chapter 5: The Birth of the Computer - From ENIAC to Apple, the Computing Machines That Changed the World

Chapter 6: The Revolution Called Game Theory - Overturning Our Perspectives on Humanity and Society

Chapter 7: War as a Game - RAND and the Science of War

Chapter 8: In Search of the Logic of Life - Self-Replicating Machines and Mind-Creating Machines

Epilogue: Neumann, what future did he come from?

·Notes ·Acknowledgements ·Translator's Note

·References ·Image Source ·Search

Preface by von Neumann, Man More Than Human

Chapter 1: The Mathematical Genius of Budapest: The Secret of the Hungarian Phenomenon

Chapter 2: Beyond Infinity - The Teenage Boy Who Saved Mathematics from Crisis

Chapter 3: Opening the Age of Quantum Mechanics - How Does God Play the Dice Game?

Chapter 4: The Manhattan Project and Nuclear War: An Apocalypse foretelling the destruction of humanity

Chapter 5: The Birth of the Computer - From ENIAC to Apple, the Computing Machines That Changed the World

Chapter 6: The Revolution Called Game Theory - Overturning Our Perspectives on Humanity and Society

Chapter 7: War as a Game - RAND and the Science of War

Chapter 8: In Search of the Logic of Life - Self-Replicating Machines and Mind-Creating Machines

Epilogue: Neumann, what future did he come from?

·Notes ·Acknowledgements ·Translator's Note

·References ·Image Source ·Search

Detailed image

Into the book

How could a country as small as a booger produce so many outstanding mathematicians and scientists? The secret is a matter of debate even among Martians, but there's widespread agreement on one hypothesis.

“If we are Martians, then one of us is an alien species from another galaxy altogether.” This is how Eugene Wigner, the Hungarian-born American physicist who won the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physics, responded when asked about this enigmatic “Hungarian phenomenon.”

“There is no such thing.

Hungarians are similar to people from other countries.

However, there is one person who needs an explanation, and that is John von Neumann.”

--- p.23, from “Chapter 1: Mathematical Geniuses of Budapest”

Neumann had no particular animosity toward quantum mechanics, which was incredibly strange.

He was much more lenient than Einstein, who nitpicked at every word.

Neumann simply wanted to know what contradictions the duality underlying quantum mechanics would produce.

Fortunately, the duality did not create any contradictions.

No matter where we draw the boundary between the quantum and classical systems, the answer the observer gets is always the same.

Thus, Neumann concluded that this boundary could be moved deep within the observer's body, even to the point just before awareness arises (wherever that may be).

This boundary is known today as the 'Heisenberg cut', but more fairly it should be called the 'Heisenberg-Neumann cut'.

--- p.100, from “Chapter 3: Opening the Era of Quantum Mechanics”

Neumann devoted nearly a third of his research time to developing the bomb.

He was probably the only researcher who knew everything about Los Alamos who was free to come and go without being locked up.

When he received a call from Los Alamos, the Army and Navy strongly insisted that their research on ballistics and shock waves was also needed.

So Neumann's theoretical research was conducted under tight security in the secure offices of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) in Washington, and small-scale explosive experiments were also carried out secretly at Woods Hole in Massachusetts.

--- p.167, from “Chapter 4: The Manhattan Project and Nuclear War”

ENIAC was a war machine born for one purpose.

But after the war ended and other uses emerged, the machine's very existence became its biggest drawback.

Among the project team members, the one who most accurately identified this problem was Neumann.

Not only team members, but there may not have been anyone in this world who knew him as well as he did.

More importantly, Neumann already had a blueprint for a "flexible computer capable of constantly changing its program." Throughout the project, the ENIAC team had recognized the machine's shortcomings and sought solutions, and Neumann's arrival gave them a boost.

--- p.209, from “Chapter 5: The Birth of the Computer”

Neumann made possible what was thought impossible.

We have developed a rigorous method of assigning numbers to the vague desires and partial tendencies of humans.

In 2011, more than 60 years after the publication of Game Theory, Nobel laureate in economics Daniel Kahneman called it “the most important theoretical book in the history of social science.”

After the publication of "Game Theory," the concepts of "utility theory" and "rational calculation," which are at the core of the theory, quickly spread beyond the ivory tower to all fields.

--- p.299, from “Chapter 6: The Revolution Called Game Theory”

Initially, Neumann focused on improving game theory at RAND.

When Williams wrote to Neumann in 1947 expressing his intention to "concentrate for some time on the application of game theory," Neumann responded very positively.

“The game theory project you have been pursuing so enthusiastically and successfully is of great interest to me as well.

“I can’t say enough about this.”26 Neumann looked closely at the game theory report submitted by the mathematicians at RAND.

Although his previous books had focused primarily on finding solutions to two-player and n-games, Neumann's interest had now shifted from finding theoretical solutions to computing practical solutions.

--- p.355, from “Chapter 7: War Became a Game”

Neumann's cellular automata became the seed of all theories that emerged in this field, and provided a spark of inspiration to the brave pioneers who set out to create life.

The kinetic automata he never completed also bore fruit.

Shortly after John Kemeny introduced Neumann's ideas to the general public, a group of scientists implemented a similar device in the real world, not on a computer.

However, the devices they created were not made of soft materials like living things, but were rigid machines made mainly of bolts and nuts.

Nanotechnology pioneer Eric Drexler called the device a "rattling replicator."

--- p.466, from “Chapter 8: In Search of the Logic of Life”

The cancer that had been eating away at Neumann's body had now reached his brain.

He muttered in Hungarian in his sleep, and called over the soldiers guarding the sickroom, muttering something unintelligible, saying, “I have an urgent message for headquarters.”

The intellect of one of the sharpest men on Earth slowly faded away.

At the last minute, Neumann asked Marina to give him a simple arithmetic problem, such as “7+4.” Neumann was unable to answer any of the several problems Marina posed, and Marina, unable to bear it any longer, burst into tears and ran out of the hospital room.

“If we are Martians, then one of us is an alien species from another galaxy altogether.” This is how Eugene Wigner, the Hungarian-born American physicist who won the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physics, responded when asked about this enigmatic “Hungarian phenomenon.”

“There is no such thing.

Hungarians are similar to people from other countries.

However, there is one person who needs an explanation, and that is John von Neumann.”

--- p.23, from “Chapter 1: Mathematical Geniuses of Budapest”

Neumann had no particular animosity toward quantum mechanics, which was incredibly strange.

He was much more lenient than Einstein, who nitpicked at every word.

Neumann simply wanted to know what contradictions the duality underlying quantum mechanics would produce.

Fortunately, the duality did not create any contradictions.

No matter where we draw the boundary between the quantum and classical systems, the answer the observer gets is always the same.

Thus, Neumann concluded that this boundary could be moved deep within the observer's body, even to the point just before awareness arises (wherever that may be).

This boundary is known today as the 'Heisenberg cut', but more fairly it should be called the 'Heisenberg-Neumann cut'.

--- p.100, from “Chapter 3: Opening the Era of Quantum Mechanics”

Neumann devoted nearly a third of his research time to developing the bomb.

He was probably the only researcher who knew everything about Los Alamos who was free to come and go without being locked up.

When he received a call from Los Alamos, the Army and Navy strongly insisted that their research on ballistics and shock waves was also needed.

So Neumann's theoretical research was conducted under tight security in the secure offices of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) in Washington, and small-scale explosive experiments were also carried out secretly at Woods Hole in Massachusetts.

--- p.167, from “Chapter 4: The Manhattan Project and Nuclear War”

ENIAC was a war machine born for one purpose.

But after the war ended and other uses emerged, the machine's very existence became its biggest drawback.

Among the project team members, the one who most accurately identified this problem was Neumann.

Not only team members, but there may not have been anyone in this world who knew him as well as he did.

More importantly, Neumann already had a blueprint for a "flexible computer capable of constantly changing its program." Throughout the project, the ENIAC team had recognized the machine's shortcomings and sought solutions, and Neumann's arrival gave them a boost.

--- p.209, from “Chapter 5: The Birth of the Computer”

Neumann made possible what was thought impossible.

We have developed a rigorous method of assigning numbers to the vague desires and partial tendencies of humans.

In 2011, more than 60 years after the publication of Game Theory, Nobel laureate in economics Daniel Kahneman called it “the most important theoretical book in the history of social science.”

After the publication of "Game Theory," the concepts of "utility theory" and "rational calculation," which are at the core of the theory, quickly spread beyond the ivory tower to all fields.

--- p.299, from “Chapter 6: The Revolution Called Game Theory”

Initially, Neumann focused on improving game theory at RAND.

When Williams wrote to Neumann in 1947 expressing his intention to "concentrate for some time on the application of game theory," Neumann responded very positively.

“The game theory project you have been pursuing so enthusiastically and successfully is of great interest to me as well.

“I can’t say enough about this.”26 Neumann looked closely at the game theory report submitted by the mathematicians at RAND.

Although his previous books had focused primarily on finding solutions to two-player and n-games, Neumann's interest had now shifted from finding theoretical solutions to computing practical solutions.

--- p.355, from “Chapter 7: War Became a Game”

Neumann's cellular automata became the seed of all theories that emerged in this field, and provided a spark of inspiration to the brave pioneers who set out to create life.

The kinetic automata he never completed also bore fruit.

Shortly after John Kemeny introduced Neumann's ideas to the general public, a group of scientists implemented a similar device in the real world, not on a computer.

However, the devices they created were not made of soft materials like living things, but were rigid machines made mainly of bolts and nuts.

Nanotechnology pioneer Eric Drexler called the device a "rattling replicator."

--- p.466, from “Chapter 8: In Search of the Logic of Life”

The cancer that had been eating away at Neumann's body had now reached his brain.

He muttered in Hungarian in his sleep, and called over the soldiers guarding the sickroom, muttering something unintelligible, saying, “I have an urgent message for headquarters.”

The intellect of one of the sharpest men on Earth slowly faded away.

At the last minute, Neumann asked Marina to give him a simple arithmetic problem, such as “7+4.” Neumann was unable to answer any of the several problems Marina posed, and Marina, unable to bear it any longer, burst into tears and ran out of the hospital room.

--- p.493-494, from “Chapter 8: In Search of the Logic of Life”

Publisher's Review

This book is a brilliant biography of one of the most brilliant, unpredictable, and ultimately dangerous mathematicians of the 20th century.

― The Financial Times

Von Neumann, a name encountered in almost every area that defines modern society.

― A vivid account of the revolutionary history of 20th-century science through the life of an extraordinary scientist.

Is "artificial intelligence" a technological challenge or a societal one? The impact of AI, which has grown rapidly in recent years, has not been confined to industry.

Artificial intelligence, with its ability to learn on its own, is expanding its reach across fields such as science and R&D, art, medicine, law, the military, and even cooking.

If we trace back the origins of these changes, we come across someone.

That's John von Neumann.

Von Neumann is a difficult figure to define.

He is a mathematician and physicist, and studied chemistry in college.

From his teenage years, he solved many of the most difficult problems in 20th-century mathematics, discovered important theorems in quantum mechanics, participated in the Manhattan Project to develop nuclear weapons, and in the process contributed to the birth of the computer.

It gave birth to game theory, completely changing the way we view modern economy and society, and it also designed the origin of machines that think and replicate themselves by discovering the logic of life.

He was the first to use the term “singularity” to refer to the point where machines surpass human capabilities, “unified the fields of computer science and neuroscience” (Ray Kurzweil), and laid the theoretical foundations for molecular biology.

Perhaps because his name can be found in almost every field that defines modern society, world-renowned cognitive philosopher Daniel Dennett once said, “I doubt if there is any field in the history of thought in the latter half of the 20th century where von Neumann could not be called the ‘father of ~’.”

Von Neumann's life spans an entire century of scientific history.

― Not just the story of one man, but the footsteps of a prophet who runs through the entire history of 20th-century civilization.

This book, "John von Neumann: The Man from the Future," is a book written by Ananyo Bhattacharya, a science journalist who served as a senior editor for the academic journal "Nature" for 15 years, and summarizes the life of John von Neumann, his academic achievements, and his contributions to humanity.

The greatest strength of this book is that it does not simply trace the life of a scientist named von Neumann, but is structured so that readers can explore the entire history of 20th-century civilization along with von Neumann's story.

When explaining von Neumann's contributions to quantum mechanics, the author organized the main issues from the birth of quantum mechanics, and to describe von Neumann's role in the Manhattan Project, he looked at the principles of nuclear fission and nuclear fusion, the mechanism of utilizing them in weapons, and the numerous scientific advances made during the World Wars and the Cold War, from the Manhattan Project to the Institute for Advanced Study and the RAND Corporation later on.

When discussing Neumann's activities, which heralded the birth of the computer age, we present the history from the emergence of the concept of an "automatic calculating machine" to the birth and limitations of ENIAC, and its overcoming to create the first programmable computer, EDVAC.

In the early 20th century, as the discipline of economics emerged and scientific approaches emerged, Neumann's influence led to the birth of a new concept called game theory, and this book explains the entire process in detail.

The concept of 21st-century artificial intelligence emerged in computer development.

From the leaps forward in mathematics and physics to the revolutionary discoveries of the atomic bomb, computers, and artificial intelligence.

Neumann gave birth to the concept of artificial intelligence in the process of developing a simple calculating machine into a modern computer.

After that, he developed the theory of automata and proposed the idea of a self-replicating machine that can replicate itself, which later led to the creation of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and even synthetic life.

The author describes in detail the meeting between Alan Turing and Neumann, the progress and limitations of the ENIAC project, and how the automata theory proposed by Neumann was later developed by other scientists.

Thus, although this book follows the footsteps of one man, von Neumann, in chronological order, it can be said that what it contains is actually the entire history of 20th-century civilization.

The early 20th century saw groundbreaking discoveries in mathematics and physics, and two world wars soon followed, allowing humanity to leverage these scientific advances to develop weapons capable of wiping out virtually all life on Earth.

As the era of thermonuclear war passed and the Cold War arrived, humanity refined its theories to utilize the weapon called economy in a more sophisticated and precise way.

What an advanced industrial society needed was a machine with excellent computing power that could make judgments and decisions on its own without being ordered.

This led to the development of computers and the emergence of artificial intelligence, which grew into a field that would define the 21st century.

In this way, Neumann's science, like the self-replicating machine he proposed, continuously spread, replicated, and evolved.

A person whose only pleasure is thinking

―A perfect genius or an immature human? What kind of person was von Neumann?

Aside from his numerous studies and achievements, there is a certain degree of agreement on the human assessment of von Neumann.

He is an overly rational person and extremely immature in interpersonal relationships.

Von Neumann's only daughter, Marina, described him as a man who had both the qualities of a "cynical scientist and a kind man," a man who was constantly fighting fiercely between two opposing personalities within him, all the while trying to appear as generous and honorable as possible on the outside, a "great enigma of nature."

Neumann had no interest or talent for physical activity other than studying.

He was not good at playing musical instruments and hated sports so much that when his second wife suggested they go skiing, he said without a moment's hesitation, "Let's get a divorce."

It is said that although he developed a method to always win at chess games, his actual chess skills never went beyond intermediate level.

I liked driving, but I wasn't very good at it, so I had to change my car once a year.

Because the car turned into scrap metal in just one year.

It is said that during his time at Princeton, the curved road where he frequently had accidents was nicknamed “Neumann Corner.”

There is one thing in common in the evaluations of Neumann by those around him.

That is, he was the person who loved thinking (thinking) more than anyone else.

He was “a man whose only pleasure was thinking” (Edward Teller), a “severe thinking addict” (Peter Lacks), and “a person who would have built a computer out of Lego blocks if they had existed back then” (Marina von Neumann).

He had a “desire to bring order and rationality to a chaotic and irrational world,” and he had “an extraordinary ability to transform all the world’s problems into problems of mathematical logic” (Freeman Dyson). Based on this, he was also a person who “proved what most mathematicians could prove, but he proved what he wanted to prove” (Rosa Peter).

A panorama of exchange and creativity among the great geniuses who shaped our time.

― From Einstein, Gödel, Oppenheimer to Neumann's second wife, Clara Dann

As we read this book, we will encounter the names of many people who are familiar to us, including Kurt Gödel, Erwin Schrödinger, Albert Einstein, Richard Feynman, Edward Teller, Oskar Morgenstern, Bernhard Riemann, Robert Oppenheimer, Alan Turing, John Nash, Lloyd Shapley, and David Hilbert.

This book provides a fascinating introduction to Neumann's personal relationships and stories with those who have achieved remarkable things in their respective fields.

In this book, author Ananya Bhattacharya focuses on the life of a person who is not as well known as the famous people: Clara Dann, Neumann's second wife.

The author details Clara's accomplishments, which she underestimated due to "the side effects of marrying the smartest man on Earth."

Clara, like most women at the time, was an ordinary person who had never attended college.

The couple married in the winter of 1938 and moved to Princeton, USA.

During the war, she happened to work at the Princeton University Census Bureau, where her abilities were recognized, and she later became, in effect, the first coder (programmer) in human history, developing a Monte Carlo program that took full advantage of ENIAC's numerical processing capabilities to calculate the trajectories of neutrons as they spread out in all directions inside a nuclear bomb.

As we read the stories of those who intellectually interacted with von Neumann and revolutionized new knowledge and ideas, the history of civilization in the 20th century unfolds before us like a panorama.

By following the trajectory of his life, which has been less highlighted than that of Einstein, Feynman, and Oppenheimer, I hope to properly evaluate von Neumann, the "man from the future," and enjoy the 21st century he created in a new way.

― The Financial Times

Von Neumann, a name encountered in almost every area that defines modern society.

― A vivid account of the revolutionary history of 20th-century science through the life of an extraordinary scientist.

Is "artificial intelligence" a technological challenge or a societal one? The impact of AI, which has grown rapidly in recent years, has not been confined to industry.

Artificial intelligence, with its ability to learn on its own, is expanding its reach across fields such as science and R&D, art, medicine, law, the military, and even cooking.

If we trace back the origins of these changes, we come across someone.

That's John von Neumann.

Von Neumann is a difficult figure to define.

He is a mathematician and physicist, and studied chemistry in college.

From his teenage years, he solved many of the most difficult problems in 20th-century mathematics, discovered important theorems in quantum mechanics, participated in the Manhattan Project to develop nuclear weapons, and in the process contributed to the birth of the computer.

It gave birth to game theory, completely changing the way we view modern economy and society, and it also designed the origin of machines that think and replicate themselves by discovering the logic of life.

He was the first to use the term “singularity” to refer to the point where machines surpass human capabilities, “unified the fields of computer science and neuroscience” (Ray Kurzweil), and laid the theoretical foundations for molecular biology.

Perhaps because his name can be found in almost every field that defines modern society, world-renowned cognitive philosopher Daniel Dennett once said, “I doubt if there is any field in the history of thought in the latter half of the 20th century where von Neumann could not be called the ‘father of ~’.”

Von Neumann's life spans an entire century of scientific history.

― Not just the story of one man, but the footsteps of a prophet who runs through the entire history of 20th-century civilization.

This book, "John von Neumann: The Man from the Future," is a book written by Ananyo Bhattacharya, a science journalist who served as a senior editor for the academic journal "Nature" for 15 years, and summarizes the life of John von Neumann, his academic achievements, and his contributions to humanity.

The greatest strength of this book is that it does not simply trace the life of a scientist named von Neumann, but is structured so that readers can explore the entire history of 20th-century civilization along with von Neumann's story.

When explaining von Neumann's contributions to quantum mechanics, the author organized the main issues from the birth of quantum mechanics, and to describe von Neumann's role in the Manhattan Project, he looked at the principles of nuclear fission and nuclear fusion, the mechanism of utilizing them in weapons, and the numerous scientific advances made during the World Wars and the Cold War, from the Manhattan Project to the Institute for Advanced Study and the RAND Corporation later on.

When discussing Neumann's activities, which heralded the birth of the computer age, we present the history from the emergence of the concept of an "automatic calculating machine" to the birth and limitations of ENIAC, and its overcoming to create the first programmable computer, EDVAC.

In the early 20th century, as the discipline of economics emerged and scientific approaches emerged, Neumann's influence led to the birth of a new concept called game theory, and this book explains the entire process in detail.

The concept of 21st-century artificial intelligence emerged in computer development.

From the leaps forward in mathematics and physics to the revolutionary discoveries of the atomic bomb, computers, and artificial intelligence.

Neumann gave birth to the concept of artificial intelligence in the process of developing a simple calculating machine into a modern computer.

After that, he developed the theory of automata and proposed the idea of a self-replicating machine that can replicate itself, which later led to the creation of artificial intelligence, machine learning, and even synthetic life.

The author describes in detail the meeting between Alan Turing and Neumann, the progress and limitations of the ENIAC project, and how the automata theory proposed by Neumann was later developed by other scientists.

Thus, although this book follows the footsteps of one man, von Neumann, in chronological order, it can be said that what it contains is actually the entire history of 20th-century civilization.

The early 20th century saw groundbreaking discoveries in mathematics and physics, and two world wars soon followed, allowing humanity to leverage these scientific advances to develop weapons capable of wiping out virtually all life on Earth.

As the era of thermonuclear war passed and the Cold War arrived, humanity refined its theories to utilize the weapon called economy in a more sophisticated and precise way.

What an advanced industrial society needed was a machine with excellent computing power that could make judgments and decisions on its own without being ordered.

This led to the development of computers and the emergence of artificial intelligence, which grew into a field that would define the 21st century.

In this way, Neumann's science, like the self-replicating machine he proposed, continuously spread, replicated, and evolved.

A person whose only pleasure is thinking

―A perfect genius or an immature human? What kind of person was von Neumann?

Aside from his numerous studies and achievements, there is a certain degree of agreement on the human assessment of von Neumann.

He is an overly rational person and extremely immature in interpersonal relationships.

Von Neumann's only daughter, Marina, described him as a man who had both the qualities of a "cynical scientist and a kind man," a man who was constantly fighting fiercely between two opposing personalities within him, all the while trying to appear as generous and honorable as possible on the outside, a "great enigma of nature."

Neumann had no interest or talent for physical activity other than studying.

He was not good at playing musical instruments and hated sports so much that when his second wife suggested they go skiing, he said without a moment's hesitation, "Let's get a divorce."

It is said that although he developed a method to always win at chess games, his actual chess skills never went beyond intermediate level.

I liked driving, but I wasn't very good at it, so I had to change my car once a year.

Because the car turned into scrap metal in just one year.

It is said that during his time at Princeton, the curved road where he frequently had accidents was nicknamed “Neumann Corner.”

There is one thing in common in the evaluations of Neumann by those around him.

That is, he was the person who loved thinking (thinking) more than anyone else.

He was “a man whose only pleasure was thinking” (Edward Teller), a “severe thinking addict” (Peter Lacks), and “a person who would have built a computer out of Lego blocks if they had existed back then” (Marina von Neumann).

He had a “desire to bring order and rationality to a chaotic and irrational world,” and he had “an extraordinary ability to transform all the world’s problems into problems of mathematical logic” (Freeman Dyson). Based on this, he was also a person who “proved what most mathematicians could prove, but he proved what he wanted to prove” (Rosa Peter).

A panorama of exchange and creativity among the great geniuses who shaped our time.

― From Einstein, Gödel, Oppenheimer to Neumann's second wife, Clara Dann

As we read this book, we will encounter the names of many people who are familiar to us, including Kurt Gödel, Erwin Schrödinger, Albert Einstein, Richard Feynman, Edward Teller, Oskar Morgenstern, Bernhard Riemann, Robert Oppenheimer, Alan Turing, John Nash, Lloyd Shapley, and David Hilbert.

This book provides a fascinating introduction to Neumann's personal relationships and stories with those who have achieved remarkable things in their respective fields.

In this book, author Ananya Bhattacharya focuses on the life of a person who is not as well known as the famous people: Clara Dann, Neumann's second wife.

The author details Clara's accomplishments, which she underestimated due to "the side effects of marrying the smartest man on Earth."

Clara, like most women at the time, was an ordinary person who had never attended college.

The couple married in the winter of 1938 and moved to Princeton, USA.

During the war, she happened to work at the Princeton University Census Bureau, where her abilities were recognized, and she later became, in effect, the first coder (programmer) in human history, developing a Monte Carlo program that took full advantage of ENIAC's numerical processing capabilities to calculate the trajectories of neutrons as they spread out in all directions inside a nuclear bomb.

As we read the stories of those who intellectually interacted with von Neumann and revolutionized new knowledge and ideas, the history of civilization in the 20th century unfolds before us like a panorama.

By following the trajectory of his life, which has been less highlighted than that of Einstein, Feynman, and Oppenheimer, I hope to properly evaluate von Neumann, the "man from the future," and enjoy the 21st century he created in a new way.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 15, 2023

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 576 pages | 856g | 142*217*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788901275161

- ISBN10: 8901275163

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)