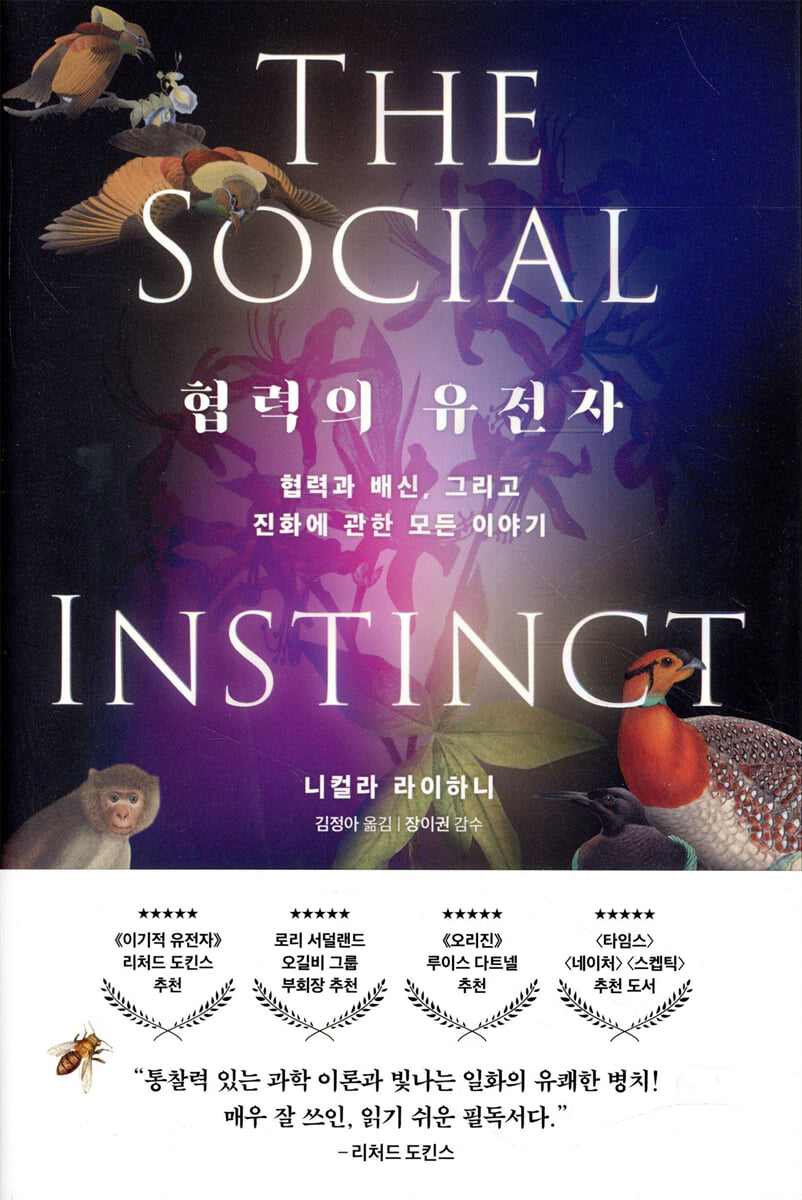

The gene of cooperation

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

Cooperation, the force that has guided humanityBecause humans are multicellular organisms made up of cooperation between cells, they possess genes for cooperation.

From family formation and community formation to working with others toward a common goal, humanity has evolved and developed through cooperation in all aspects, and the power of cooperation will enable us to overcome future crises.

October 14, 2022. Natural Science PD Ahn Hyeon-jae

“Cooperation has made the world, from the small to the truly magnificent!”

On the evolution of all life through cooperation and betrayal

Recently, we have faced several crises that we cannot respond to on our own.

The emergence of COVID-19 has brought us to an unprecedented pandemic, and we are experiencing the various consequences of human selfish behavior, such as climate change due to reckless development, and the destruction and extinction of habitats for plants and animals.

So are we truly "selfish" beings? Perhaps this is the most important question we have ever faced, or will ever face.

Nicola Raihany, a professor of biology at University College London (UCL) and a world-renowned evolutionary psychologist, points out in her first book, The Cooperation Gene, that the nature of humans, which has been misunderstood as selfish until now, is actually 'cooperation', and that cooperation is the force that made the birth and evolution of all life possible.

Nicola Reihani, who has conducted extensive and in-depth research across fields and species, including psychology and evolutionary biology, says that we humans, too, were able to exist through cooperation.

This is because humans are multicellular organisms made up of tens of trillions of cells working together.

He also explains that the various phenomena and groups that make up human society, such as the reason we live with our families, the existence of grandmothers, the causes of paranoia and jealousy, and the reasons we deceive one another, were possible because of cooperation.

From this perspective, "The Cooperation Gene" points out that cooperation is a part of human history and a factor that will have a significant impact on the future we will face.

To better understand the power of cooperation and its evolution, we will examine not only the history of human evolution but also the stories of other diverse social life forms on Earth.

Through this, we will learn more about ourselves and the other species that share this planet, and along the way, we will rediscover that cooperation is truly human nature and the true force that has driven all of our evolution and prosperity.

On the evolution of all life through cooperation and betrayal

Recently, we have faced several crises that we cannot respond to on our own.

The emergence of COVID-19 has brought us to an unprecedented pandemic, and we are experiencing the various consequences of human selfish behavior, such as climate change due to reckless development, and the destruction and extinction of habitats for plants and animals.

So are we truly "selfish" beings? Perhaps this is the most important question we have ever faced, or will ever face.

Nicola Raihany, a professor of biology at University College London (UCL) and a world-renowned evolutionary psychologist, points out in her first book, The Cooperation Gene, that the nature of humans, which has been misunderstood as selfish until now, is actually 'cooperation', and that cooperation is the force that made the birth and evolution of all life possible.

Nicola Reihani, who has conducted extensive and in-depth research across fields and species, including psychology and evolutionary biology, says that we humans, too, were able to exist through cooperation.

This is because humans are multicellular organisms made up of tens of trillions of cells working together.

He also explains that the various phenomena and groups that make up human society, such as the reason we live with our families, the existence of grandmothers, the causes of paranoia and jealousy, and the reasons we deceive one another, were possible because of cooperation.

From this perspective, "The Cooperation Gene" points out that cooperation is a part of human history and a factor that will have a significant impact on the future we will face.

To better understand the power of cooperation and its evolution, we will examine not only the history of human evolution but also the stories of other diverse social life forms on Earth.

Through this, we will learn more about ourselves and the other species that share this planet, and along the way, we will rediscover that cooperation is truly human nature and the true force that has driven all of our evolution and prosperity.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Praise poured in for "The Gene of Cooperation"

Entering

Part 1: Cooperation, Creating Life

Eyes that make your blood run cold

Evolution, Inventing Individuals

Enemy within

Part 2: The Birth of a Family

Mom and Dad

Ants and grasshoppers

Nice to meet you, baby

The Teachings of the Araknoreori Chire

Long live the Queen

A bloody battle for the throne

Part 3 Beyond the Family

Betrayal or cooperation?

Taming the Traitor

valuable reputation

tightrope walking

Part 4: The Extraordinary Ape

Facebook for chimpanzees

The Two Faces of Cooperation

The danger lurking in our hearts

Taking back control

victims of collaboration

To those who are grateful

main

Entering

Part 1: Cooperation, Creating Life

Eyes that make your blood run cold

Evolution, Inventing Individuals

Enemy within

Part 2: The Birth of a Family

Mom and Dad

Ants and grasshoppers

Nice to meet you, baby

The Teachings of the Araknoreori Chire

Long live the Queen

A bloody battle for the throne

Part 3 Beyond the Family

Betrayal or cooperation?

Taming the Traitor

valuable reputation

tightrope walking

Part 4: The Extraordinary Ape

Facebook for chimpanzees

The Two Faces of Cooperation

The danger lurking in our hearts

Taking back control

victims of collaboration

To those who are grateful

main

Detailed image

Into the book

Our social nature, our human nature, has led us to a pandemic.

But the only way out of this is through sociality.

It's not clear when we'll get out of this crisis, but we do know how to get out of it.

To combat COVID-19, we must suppress our most basic instincts, the ones that whisper to us to socialize in times of crisis.

We must accept the constraints that govern where, with whom, and what we do.

Scientists must dedicate themselves to achieving the common goal of developing a vaccine, while essential workers must provide the critical services and supplies we need to survive.

Political leaders must be considerate not only of their constituents but also of people living in other countries and even beyond.

Yes, that's right.

We must cooperate with each other.

---From "Entering"

Describing genes as selfish does not mean that they contain traits such as immorality, cunning, and spitefulness that are considered characteristics of selfish humans.

Nor does it refer to genes associated with selfish traits that exist only in the bodies of extremely evil individuals.

All 26,000 genes in our bodies could be described as "selfish" genes, or, to put it mildly, "self-centered" genes.

This means that each gene has its own 'interests' that it considers most important.

---From "01_Chilling Eyes"

The most aggressive and invasive cancers arise from these diverse, mutually supportive communities of cells.

(…) If we look at cancer from this perspective, a more universal point becomes clear.

What is cooperation on one side is competition on the other.

Cancer cell colonies cooperate with each other in multicellular organisms, but this cooperation comes at a great cost to the host.

So a bitter and disappointing situation arises.

Even cancer that wins the battle ends up losing the war.

Most cancers are not contagious and have no way to leave the host body.

Even if you briefly hijack a ship to achieve your goal, if the ship sinks, you die along with it.

---From "03_The Enemy Within"

They say that conflicts arise everywhere in the process of parents caring for their young.

Even if a male and female raise their young together, they are tempted to invest slightly less than their partner, and to raise their young only twice while their partner raises them three times.

Experiments have shown that when a female geese trusts a male, she becomes more lazy and passes on more of the heavy lifting of childcare to him.

This female strategy leads to the very unfortunate result mentioned above, whereby offspring with both a mother and a father grow up to be more unhealthy than offspring with only a mother.

So how can we avoid this conflict? (…) Theorists predict that if one parent neglects childcare, the other parent will shoulder more of the burden rather than investing less than the other parent, making up for the shortfall.

The important point here is that even if that were the case, it would not completely fill the gap.

---From "05_The Ant and the Grasshopper"

Thanks to numerous long-term studies that have shed light on animal behavior, we now know a great deal about how baboons, meerkats, baboons, and other interesting species cooperate.

This valuable knowledge allows us to see how similar we are to other social animals and how diverse and complex cooperation can be.

Collaboration enables us to accomplish many different things.

As we saw in the case of the songbird, cooperation can help detect predators, protect the nest, and provide food and education for the chicks.

But sometimes cooperation changes the individual.

It causes irreversible and permanent changes in the entity to make it a better helper.

---From "07_The Teachings of the Araknorae Kkori Chire"

Why does a woman's fertility decline so dramatically in her late 30s? Why do they persist in infertility, even when their reproductive prospects seem to be at an impasse? To answer these questions, we need to examine menopause from an evolutionary perspective.

Then we can see that menopause is the product of an evolutionary battle between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law that has been going on for countless years.

(…) According to this data, when a mother-in-law gave birth to and raised a child at the same time as her daughter-in-law, both children had difficulty surviving.

The price of this simultaneous reproduction was enormous.

In cases where there was reproductive competition between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law, less than half of the children survived to the age of 15.

---From "08_Long Live the Queen"

Cooperation creates not only a collection of individuals but also stable family groups in which some individuals help others reproduce and raise children.

But sometimes cooperation can hinder, rather than help, the evolution of larger, more complex groups.

Recall how cancer cells, as we saw in Part 1, work together to harm the host organism.

(…) Therefore, counterintuitively, it may be that hindering cooperation can actually stabilize society, especially when the benefits of such alliances are detrimental to the group as a whole.

This is a fundamental challenge that runs deep in cooperation.

And we humans are not immune to the influence of this challenge.

Cooperation is both essential to humanity's collective success and the greatest threat to that success.

---From "09_Bloody Battle for the Throne"

Even in the course of human evolution, a system of help and exchange based on needs was not unusual but commonplace.

Even today, such systems are common in many hunter-gatherer societies and many non-industrial societies.

This system does not replace the reciprocal sharing system, but coexists with it.

(…) In social interactions, not counting every penny from our colleagues is an unspoken message that says, 'We depend on each other.'

Interdependence means that your interests depend on the well-being of your colleagues, so interdependent colleagues don't have to calculate the cost-benefit ratio every time they interact.

The reason I feel bad for a friend who insists on buying me coffee today because I bought him coffee last week is because it sounds like he doesn't consider me an important friend, that he's putting a higher price on a cup of coffee than his own self-interest in my well-being.

---From "10_Betrayal or Cooperation"

We are not the only image-conscious species.

The blue-lined cleaner wrasse is also surprisingly similar to us here.

They try to look good to others.

As you know, there is a conflict of interest between the bluefin tuna and the customer fish.

The customer wants the cleaner wrasse to get rid of parasites, and the cleaner wrasse wants to eat the customer's mucus and scales.

Unlike humans, cleaner wrasses and customer fish can't sit down and have a conversation, and they can't leave reviews of poor service.

Yet, both sides manage to defuse the tension in surprisingly similar ways to our own.

---From "12_Precious Reputation"

We reflexively divide others into 'in-group' and 'out-group'.

However, the classification criteria are completely arbitrary (according to previous experiments, classifications were made based on criteria such as the color of the name tag and whether one liked Picasso or Monet).

Our tendency to be overly partial is a perverse consequence of our highly cooperative nature.

Early humans were increasingly able to overcome the challenges nature presented thanks to their collaborative efforts.

Food and water shortages, and the threat of dangerous predators were all mitigated through cooperation.

But that wind has made others emerge as the main threat.

The opponent in the fight was no longer nature.

It was us humans.

---From "15_The Two Faces of Cooperation"

We must harness these capabilities if we are to have any hope of solving the global problems facing us.

We need to create effective systems, such as rules, agreements, and incentives, that encourage long-term perspectives and cooperation rather than immediate selfish interests.

We know how to foresee better solutions.

I know how to draw a brighter world.

Know how to design social rules that encourage people to cooperate.

(…) No matter what anyone says, the key factor that led us to success is cooperation.

But the only way out of this is through sociality.

It's not clear when we'll get out of this crisis, but we do know how to get out of it.

To combat COVID-19, we must suppress our most basic instincts, the ones that whisper to us to socialize in times of crisis.

We must accept the constraints that govern where, with whom, and what we do.

Scientists must dedicate themselves to achieving the common goal of developing a vaccine, while essential workers must provide the critical services and supplies we need to survive.

Political leaders must be considerate not only of their constituents but also of people living in other countries and even beyond.

Yes, that's right.

We must cooperate with each other.

---From "Entering"

Describing genes as selfish does not mean that they contain traits such as immorality, cunning, and spitefulness that are considered characteristics of selfish humans.

Nor does it refer to genes associated with selfish traits that exist only in the bodies of extremely evil individuals.

All 26,000 genes in our bodies could be described as "selfish" genes, or, to put it mildly, "self-centered" genes.

This means that each gene has its own 'interests' that it considers most important.

---From "01_Chilling Eyes"

The most aggressive and invasive cancers arise from these diverse, mutually supportive communities of cells.

(…) If we look at cancer from this perspective, a more universal point becomes clear.

What is cooperation on one side is competition on the other.

Cancer cell colonies cooperate with each other in multicellular organisms, but this cooperation comes at a great cost to the host.

So a bitter and disappointing situation arises.

Even cancer that wins the battle ends up losing the war.

Most cancers are not contagious and have no way to leave the host body.

Even if you briefly hijack a ship to achieve your goal, if the ship sinks, you die along with it.

---From "03_The Enemy Within"

They say that conflicts arise everywhere in the process of parents caring for their young.

Even if a male and female raise their young together, they are tempted to invest slightly less than their partner, and to raise their young only twice while their partner raises them three times.

Experiments have shown that when a female geese trusts a male, she becomes more lazy and passes on more of the heavy lifting of childcare to him.

This female strategy leads to the very unfortunate result mentioned above, whereby offspring with both a mother and a father grow up to be more unhealthy than offspring with only a mother.

So how can we avoid this conflict? (…) Theorists predict that if one parent neglects childcare, the other parent will shoulder more of the burden rather than investing less than the other parent, making up for the shortfall.

The important point here is that even if that were the case, it would not completely fill the gap.

---From "05_The Ant and the Grasshopper"

Thanks to numerous long-term studies that have shed light on animal behavior, we now know a great deal about how baboons, meerkats, baboons, and other interesting species cooperate.

This valuable knowledge allows us to see how similar we are to other social animals and how diverse and complex cooperation can be.

Collaboration enables us to accomplish many different things.

As we saw in the case of the songbird, cooperation can help detect predators, protect the nest, and provide food and education for the chicks.

But sometimes cooperation changes the individual.

It causes irreversible and permanent changes in the entity to make it a better helper.

---From "07_The Teachings of the Araknorae Kkori Chire"

Why does a woman's fertility decline so dramatically in her late 30s? Why do they persist in infertility, even when their reproductive prospects seem to be at an impasse? To answer these questions, we need to examine menopause from an evolutionary perspective.

Then we can see that menopause is the product of an evolutionary battle between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law that has been going on for countless years.

(…) According to this data, when a mother-in-law gave birth to and raised a child at the same time as her daughter-in-law, both children had difficulty surviving.

The price of this simultaneous reproduction was enormous.

In cases where there was reproductive competition between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law, less than half of the children survived to the age of 15.

---From "08_Long Live the Queen"

Cooperation creates not only a collection of individuals but also stable family groups in which some individuals help others reproduce and raise children.

But sometimes cooperation can hinder, rather than help, the evolution of larger, more complex groups.

Recall how cancer cells, as we saw in Part 1, work together to harm the host organism.

(…) Therefore, counterintuitively, it may be that hindering cooperation can actually stabilize society, especially when the benefits of such alliances are detrimental to the group as a whole.

This is a fundamental challenge that runs deep in cooperation.

And we humans are not immune to the influence of this challenge.

Cooperation is both essential to humanity's collective success and the greatest threat to that success.

---From "09_Bloody Battle for the Throne"

Even in the course of human evolution, a system of help and exchange based on needs was not unusual but commonplace.

Even today, such systems are common in many hunter-gatherer societies and many non-industrial societies.

This system does not replace the reciprocal sharing system, but coexists with it.

(…) In social interactions, not counting every penny from our colleagues is an unspoken message that says, 'We depend on each other.'

Interdependence means that your interests depend on the well-being of your colleagues, so interdependent colleagues don't have to calculate the cost-benefit ratio every time they interact.

The reason I feel bad for a friend who insists on buying me coffee today because I bought him coffee last week is because it sounds like he doesn't consider me an important friend, that he's putting a higher price on a cup of coffee than his own self-interest in my well-being.

---From "10_Betrayal or Cooperation"

We are not the only image-conscious species.

The blue-lined cleaner wrasse is also surprisingly similar to us here.

They try to look good to others.

As you know, there is a conflict of interest between the bluefin tuna and the customer fish.

The customer wants the cleaner wrasse to get rid of parasites, and the cleaner wrasse wants to eat the customer's mucus and scales.

Unlike humans, cleaner wrasses and customer fish can't sit down and have a conversation, and they can't leave reviews of poor service.

Yet, both sides manage to defuse the tension in surprisingly similar ways to our own.

---From "12_Precious Reputation"

We reflexively divide others into 'in-group' and 'out-group'.

However, the classification criteria are completely arbitrary (according to previous experiments, classifications were made based on criteria such as the color of the name tag and whether one liked Picasso or Monet).

Our tendency to be overly partial is a perverse consequence of our highly cooperative nature.

Early humans were increasingly able to overcome the challenges nature presented thanks to their collaborative efforts.

Food and water shortages, and the threat of dangerous predators were all mitigated through cooperation.

But that wind has made others emerge as the main threat.

The opponent in the fight was no longer nature.

It was us humans.

---From "15_The Two Faces of Cooperation"

We must harness these capabilities if we are to have any hope of solving the global problems facing us.

We need to create effective systems, such as rules, agreements, and incentives, that encourage long-term perspectives and cooperation rather than immediate selfish interests.

We know how to foresee better solutions.

I know how to draw a brighter world.

Know how to design social rules that encourage people to cooperate.

(…) No matter what anyone says, the key factor that led us to success is cooperation.

---From "18_Victims of Cooperation"

Publisher's Review

Are genes really 'selfish'?

The question of the selfish gene has been recurring since Richard Dawkins described it in The Selfish Gene in 1976.

But if, as Dawkins suggests, our genes are selfish, how can we explain the countless examples of "cooperation" occurring around the world? Meerkats, for example, sacrifice their own reproduction to volunteer as helpers and educate their fellow offspring.

Vampire bats, which live in large colonies, regurgitate and share the blood they have consumed with their companions who are unable to obtain blood.

Some ants are willing to sacrifice their lives to protect other ants in their colony from attack.

To understand all this, we need to revisit what exactly we mean by the word "selfish" in describing genes.

That is, describing genes as selfish does not mean that genes contain traits that are characteristic of selfish humans, such as immorality or cunning.

Our genes are selfish, which means they have 'interests' that they consider most important.

Its sole purpose is to find a way to future generations.

So, paradoxically, selfish genes can, and often do, cooperate to achieve their goals.

The concept of survival of the fittest, where only the strong survive, and the perception that being kind to others ultimately leads to harm are all too prevalent, yet countless creatures on Earth have made history through collective action and cooperation.

Cooperation is a selfish strategy.

Stories of life forms that survived and thrived through the evolution of cooperation.

So when did we first begin to cooperate, and why do we do it? Nicola Reihani, a world-renowned evolutionary psychologist, begins this fascinating journey by revealing that every conceivable human achievement has been achieved through cooperation.

Humans exist through cooperation.

Because humans are multicellular organisms made up of tens of trillions of cells that allow us to live, breathe, and run.

Therefore, the author argues that the most important moment in human history is not the beginning of agriculture or the invention of the wheel, but the very moment when a chance collaboration between genes occurred.

How on earth did we humans develop a sphere of cooperation, from our very existence, through the small community of the family, to the grand concepts of nation and world? Early humans had to hunt and gather to secure food, and to avoid starvation, they had to work together.

But it was at this point that a distinct difference from other primate species arose.

Chimpanzees, who eat fruit as their staple food, have no need to cooperate as long as they live in a jungle that resembles a "giant salad bowl."

On the other hand, we humans have had to cooperate in almost every aspect of our survival, from eating to teaching life skills and raising children.

Of course, this does not mean that the social behavior that characterizes humanity is unique to humanity.

Rather, cooperation often emerges in species that are distant from humans.

To confirm this, the authors expand the scope of their research to various species.

Her in-depth research and unique stories about the world's diverse cooperative creatures, including the short-tailed blue jay, which willingly shares resources with its peers; the meerkats, which forgo reproduction to co-parent and educate their peers' young; the squid-tailed wrasse, which forms tight-knit family groups and achieves efficient role distribution through cooperation; and the blue-lined cleaner wrasse, which cooperates with fish it knows beyond its family boundaries, continue to pique the interest of readers.

The Paradox of Cooperation: The Traitor Within

There are not only positive aspects to cooperation.

Where there is cooperation, there are always cheaters and traitors.

This also happens frequently within our bodies, as we saw earlier, and 'cancer' is a representative example.

Cancer is essentially a renegade within a multicellular organism.

They are trickster cells that refuse to cooperate and multiply, eating away at our health.

But on the other hand, cancer cells are also willing to participate in cooperation.

They band together for their own selfish gain, even though cancer wreaks havoc on the cellular community and the ultimate outcome when they triumph is suicidal.

This reveals the 'paradox of cooperation' engraved in our genes.

What is cooperation on one side may be competition on the other.

Menopause in women is also one of the cruel aspects of cooperation.

Humanity evolved to form families through cooperation.

But in this process, a unique being called ‘Grandmother’ appears.

Among the countless living creatures, there are few that have lost their reproductive function and live this long.

To understand this, we need to look at menopause from a strictly evolutionary perspective.

In other words, menopause is the product of an evolutionary battle between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law that has been going on for countless years.

If we look at historical records from before industrialization, we see that when a mother-in-law and daughter-in-law gave birth to and raised children at the same time, both children had difficulty surviving.

Therefore, if the daughter-in-law's child is indeed her son's, the mother-in-law has a stronger genetic interest in paying attention to her grandchild.

Ultimately, grandmother is a being born from the ashes of a conflict that occurred during the evolutionary process.

This forces us to confront the inconvenient truth that has always lurked behind every situation we have ever encountered.

Perhaps the essence of cooperation lies in the means by which living beings elevate their position in this world. Yet, this brutal truth also helps us understand corruption, a chronic problem in communities.

The author argues that social corruption can be seen as a form of cooperation: giving family members priority in hiring good jobs, bribing executives to secure contracts, are all cooperative activities that involve help and trust.

However, the reason I consider these activities to be evil is because the cooperation of these few inevitably brings about social costs.

Ultimately, the way to prevent this from happening and establish a foundation for social consensus and legislation can also be achieved through cooperation across society.

The key to humanity's success, no matter what anyone says, is cooperation.

The world has recently faced a very specific situation where trust among nations is collapsing and cooperation is breaking down.

When the entire society was paralyzed by COVID-19, I was faced with empty supermarket shelves as people panicked and bought everything they could.

As the number of critically ill patients increased, distrust in the national health care system grew uncontrollably.

In fact, the pandemic is not the only problem facing humanity, nor is it the most serious problem.

Human-induced climate change, habitat destruction and extinction, increased environmental pollution, nuclear weapons—these are all a depressing list of ways in which we humans have failed to cooperate to achieve the common good.

The reason these problems are difficult to solve is because they can only be solved if all of humanity 'cooperates'.

Today, the world's population is nearly 8 billion.

It is an incredible achievement.

This achievement can be attributed to our social instincts, our desire to help close friends, family, and loved ones.

But with a massive population impacting the Earth's environment, we must move beyond our natural instincts and work together in ways we've never done before.

The late Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom said that the best way to solve global problems is to "think globally but act locally."

We must trust and cooperate with people beyond those with whom we have strong relationships or with blood relatives, even with strangers, and even with people we will never meet again.

We humans have come this far thanks to cooperation.

But if we don't find the right way to leverage collaboration, our success will hold us back.

Nevertheless, the author emphasizes once again:

Cooperation is inherent in human nature, and we have the power to overcome the various crises we face.

The key factor that has led humanity to success, no matter what anyone says, is cooperation.

The question of the selfish gene has been recurring since Richard Dawkins described it in The Selfish Gene in 1976.

But if, as Dawkins suggests, our genes are selfish, how can we explain the countless examples of "cooperation" occurring around the world? Meerkats, for example, sacrifice their own reproduction to volunteer as helpers and educate their fellow offspring.

Vampire bats, which live in large colonies, regurgitate and share the blood they have consumed with their companions who are unable to obtain blood.

Some ants are willing to sacrifice their lives to protect other ants in their colony from attack.

To understand all this, we need to revisit what exactly we mean by the word "selfish" in describing genes.

That is, describing genes as selfish does not mean that genes contain traits that are characteristic of selfish humans, such as immorality or cunning.

Our genes are selfish, which means they have 'interests' that they consider most important.

Its sole purpose is to find a way to future generations.

So, paradoxically, selfish genes can, and often do, cooperate to achieve their goals.

The concept of survival of the fittest, where only the strong survive, and the perception that being kind to others ultimately leads to harm are all too prevalent, yet countless creatures on Earth have made history through collective action and cooperation.

Cooperation is a selfish strategy.

Stories of life forms that survived and thrived through the evolution of cooperation.

So when did we first begin to cooperate, and why do we do it? Nicola Reihani, a world-renowned evolutionary psychologist, begins this fascinating journey by revealing that every conceivable human achievement has been achieved through cooperation.

Humans exist through cooperation.

Because humans are multicellular organisms made up of tens of trillions of cells that allow us to live, breathe, and run.

Therefore, the author argues that the most important moment in human history is not the beginning of agriculture or the invention of the wheel, but the very moment when a chance collaboration between genes occurred.

How on earth did we humans develop a sphere of cooperation, from our very existence, through the small community of the family, to the grand concepts of nation and world? Early humans had to hunt and gather to secure food, and to avoid starvation, they had to work together.

But it was at this point that a distinct difference from other primate species arose.

Chimpanzees, who eat fruit as their staple food, have no need to cooperate as long as they live in a jungle that resembles a "giant salad bowl."

On the other hand, we humans have had to cooperate in almost every aspect of our survival, from eating to teaching life skills and raising children.

Of course, this does not mean that the social behavior that characterizes humanity is unique to humanity.

Rather, cooperation often emerges in species that are distant from humans.

To confirm this, the authors expand the scope of their research to various species.

Her in-depth research and unique stories about the world's diverse cooperative creatures, including the short-tailed blue jay, which willingly shares resources with its peers; the meerkats, which forgo reproduction to co-parent and educate their peers' young; the squid-tailed wrasse, which forms tight-knit family groups and achieves efficient role distribution through cooperation; and the blue-lined cleaner wrasse, which cooperates with fish it knows beyond its family boundaries, continue to pique the interest of readers.

The Paradox of Cooperation: The Traitor Within

There are not only positive aspects to cooperation.

Where there is cooperation, there are always cheaters and traitors.

This also happens frequently within our bodies, as we saw earlier, and 'cancer' is a representative example.

Cancer is essentially a renegade within a multicellular organism.

They are trickster cells that refuse to cooperate and multiply, eating away at our health.

But on the other hand, cancer cells are also willing to participate in cooperation.

They band together for their own selfish gain, even though cancer wreaks havoc on the cellular community and the ultimate outcome when they triumph is suicidal.

This reveals the 'paradox of cooperation' engraved in our genes.

What is cooperation on one side may be competition on the other.

Menopause in women is also one of the cruel aspects of cooperation.

Humanity evolved to form families through cooperation.

But in this process, a unique being called ‘Grandmother’ appears.

Among the countless living creatures, there are few that have lost their reproductive function and live this long.

To understand this, we need to look at menopause from a strictly evolutionary perspective.

In other words, menopause is the product of an evolutionary battle between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law that has been going on for countless years.

If we look at historical records from before industrialization, we see that when a mother-in-law and daughter-in-law gave birth to and raised children at the same time, both children had difficulty surviving.

Therefore, if the daughter-in-law's child is indeed her son's, the mother-in-law has a stronger genetic interest in paying attention to her grandchild.

Ultimately, grandmother is a being born from the ashes of a conflict that occurred during the evolutionary process.

This forces us to confront the inconvenient truth that has always lurked behind every situation we have ever encountered.

Perhaps the essence of cooperation lies in the means by which living beings elevate their position in this world. Yet, this brutal truth also helps us understand corruption, a chronic problem in communities.

The author argues that social corruption can be seen as a form of cooperation: giving family members priority in hiring good jobs, bribing executives to secure contracts, are all cooperative activities that involve help and trust.

However, the reason I consider these activities to be evil is because the cooperation of these few inevitably brings about social costs.

Ultimately, the way to prevent this from happening and establish a foundation for social consensus and legislation can also be achieved through cooperation across society.

The key to humanity's success, no matter what anyone says, is cooperation.

The world has recently faced a very specific situation where trust among nations is collapsing and cooperation is breaking down.

When the entire society was paralyzed by COVID-19, I was faced with empty supermarket shelves as people panicked and bought everything they could.

As the number of critically ill patients increased, distrust in the national health care system grew uncontrollably.

In fact, the pandemic is not the only problem facing humanity, nor is it the most serious problem.

Human-induced climate change, habitat destruction and extinction, increased environmental pollution, nuclear weapons—these are all a depressing list of ways in which we humans have failed to cooperate to achieve the common good.

The reason these problems are difficult to solve is because they can only be solved if all of humanity 'cooperates'.

Today, the world's population is nearly 8 billion.

It is an incredible achievement.

This achievement can be attributed to our social instincts, our desire to help close friends, family, and loved ones.

But with a massive population impacting the Earth's environment, we must move beyond our natural instincts and work together in ways we've never done before.

The late Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom said that the best way to solve global problems is to "think globally but act locally."

We must trust and cooperate with people beyond those with whom we have strong relationships or with blood relatives, even with strangers, and even with people we will never meet again.

We humans have come this far thanks to cooperation.

But if we don't find the right way to leverage collaboration, our success will hold us back.

Nevertheless, the author emphasizes once again:

Cooperation is inherent in human nature, and we have the power to overcome the various crises we face.

The key factor that has led humanity to success, no matter what anyone says, is cooperation.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: September 23, 2022

- Page count, weight, size: 380 pages | 530g | 140*210*25mm

- ISBN13: 9791157846153

- ISBN10: 1157846157

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)