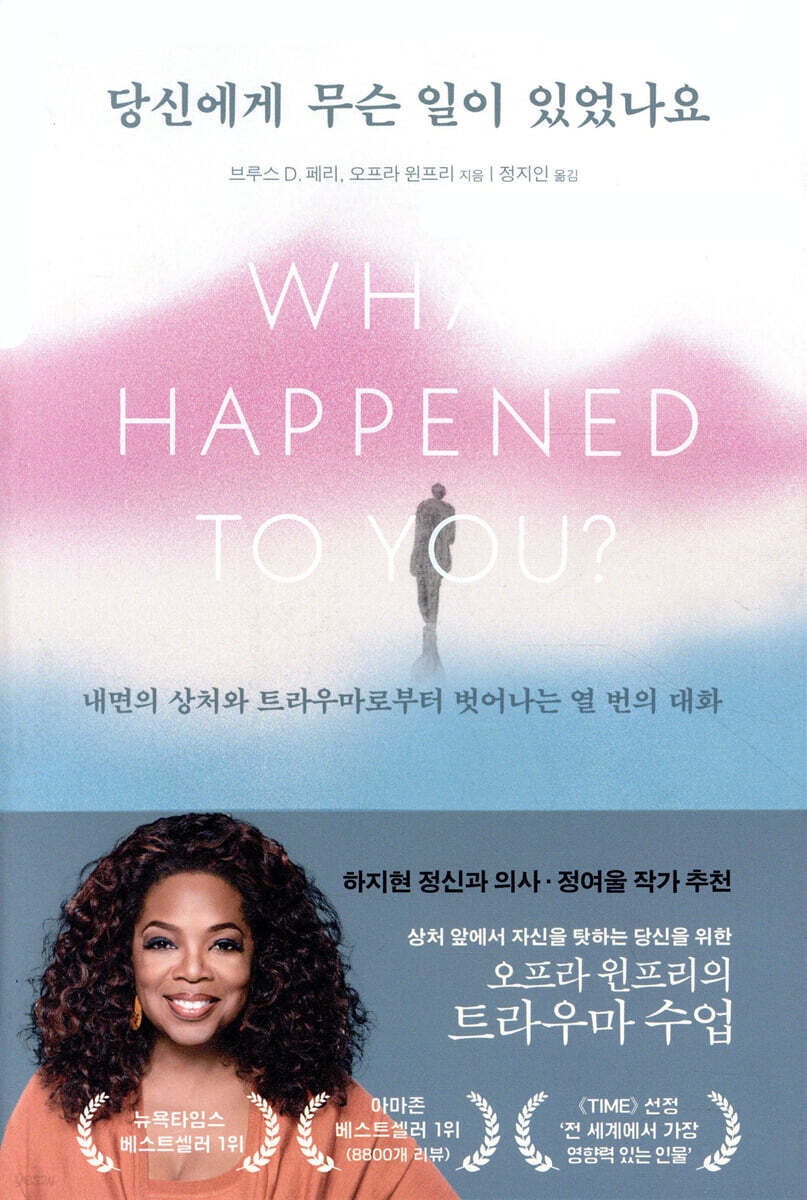

What happened to you

|

Description

Book Introduction

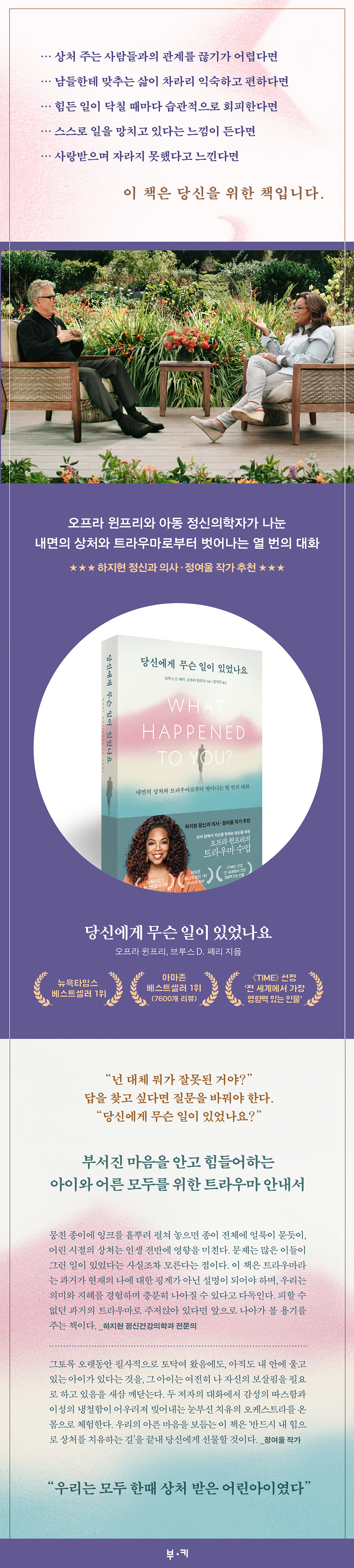

Oprah Winfrey and a child psychiatrist A Conversation on Trauma and the Brain, Healing, and Resilience When we can't break out of a pattern of repeated mistakes and failures, when no matter how hard we try, things only get worse, when we feel like we're ruining ourselves, it feels like someone is asking us with a frustrated look on their face behind our backs: “What the hell is wrong with you?” But the problem that is bothering you now may be because something happened in the past that affected your brain. Especially the pain and wounds experienced during childhood leave marks on a person's body and mind that sometimes last a lifetime. Oprah Winfrey and child psychiatrist Bruce D. Dr. Perry says that by changing the direction of the question to, “What happened to you?”, you can find the real cause and answer to the problem, and save yourself and your loved ones from the hellish state of mind. This book condenses the conversations the two have had on the topic of trauma and healing over a period of over 30 years. Oprah's warm, empathetic language, a longtime struggle with her own childhood trauma, and Dr. Perry's compassionate scientific insights, a child trauma expert, transcend the weighty subject matter and unfamiliar concepts of brain science and psychiatry, leading us deep into our own selves. This is a guide that will illuminate those who want to understand how trauma works in our brains and bodies and find their own path to healing. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Author's Note

prolog

First Conversation: How the Brain Understands the World

The present me, the past brain · What happens in the head when you are stressed · The brain creates its own code book from birth · Traumatic memories that are engraved before words · All new relationships create stress · Buttons of memories and associations that move the present

Second Conversation: Finding Balance to Sustain Life

'Rhythm' and 'regulation' that calm anxiety and restore balance. · Regulation, relationships, and rewards shape a child's worldview. · When parents collapse, children collapse too. · How to calm inner storms.

Third Conversation: How We Were Loved

The love we receive as children determines our resilience. · Cereal moments? Being fully connected. · Two responses to stress: arousal and dissociation. · People trapped in endless fear.

Fourth Conversation: What We Call Trauma

What experiences become traumatic? · Myths and truths about adverse childhood experiences · The risk of adversity depends on connectivity and timing · What is the right amount of healing? · Four symptoms that identify post-traumatic stress disorder

Conversation Five: Connecting the Dots

Trauma that is passed down through generations · Ancestral trauma is etched into our DNA · The impact of trauma on physical health · Bottom-up processes in the brain · Neural networks that open only to safe and intimate partners

Conversation Six: Moving from Coping to Healing

Neglect that has a devastating impact on brain development · Outsourced attention and love to smartphones · Good dissociation as a healthy coping mechanism · Sensitized dissociation that breeds avoidance and compliance · Healing begins with recognizing patterns

Seventh Conversation: Wisdom from Trauma

The Irreversibility of Trauma · Three Elements for Building Resilience · The Path from Pain to Wisdom · A Healing Community · No One Should Face Everything Alone

Conversation Eight: Our Brains, Our Biases, Our Systems

Social awareness of trauma · Education system that understands trauma · There is more than one tool for healing · Prejudice that starts from the first experience · Unconscious filter that acts on implicit bias · From individual change to systemic change

Ninth Conversation: Modern Society's Hunger for Relationships

The Vulnerability Caused by Relationship Poverty · The Disease of Disconnection and Loneliness · We Must Reconnect

Tenth Conversation: What We Need Now

The order and steps to healing · You can't be anything without taking care of yourself · Learning and growing from trauma

Epilogue

References

Acknowledgements

prolog

First Conversation: How the Brain Understands the World

The present me, the past brain · What happens in the head when you are stressed · The brain creates its own code book from birth · Traumatic memories that are engraved before words · All new relationships create stress · Buttons of memories and associations that move the present

Second Conversation: Finding Balance to Sustain Life

'Rhythm' and 'regulation' that calm anxiety and restore balance. · Regulation, relationships, and rewards shape a child's worldview. · When parents collapse, children collapse too. · How to calm inner storms.

Third Conversation: How We Were Loved

The love we receive as children determines our resilience. · Cereal moments? Being fully connected. · Two responses to stress: arousal and dissociation. · People trapped in endless fear.

Fourth Conversation: What We Call Trauma

What experiences become traumatic? · Myths and truths about adverse childhood experiences · The risk of adversity depends on connectivity and timing · What is the right amount of healing? · Four symptoms that identify post-traumatic stress disorder

Conversation Five: Connecting the Dots

Trauma that is passed down through generations · Ancestral trauma is etched into our DNA · The impact of trauma on physical health · Bottom-up processes in the brain · Neural networks that open only to safe and intimate partners

Conversation Six: Moving from Coping to Healing

Neglect that has a devastating impact on brain development · Outsourced attention and love to smartphones · Good dissociation as a healthy coping mechanism · Sensitized dissociation that breeds avoidance and compliance · Healing begins with recognizing patterns

Seventh Conversation: Wisdom from Trauma

The Irreversibility of Trauma · Three Elements for Building Resilience · The Path from Pain to Wisdom · A Healing Community · No One Should Face Everything Alone

Conversation Eight: Our Brains, Our Biases, Our Systems

Social awareness of trauma · Education system that understands trauma · There is more than one tool for healing · Prejudice that starts from the first experience · Unconscious filter that acts on implicit bias · From individual change to systemic change

Ninth Conversation: Modern Society's Hunger for Relationships

The Vulnerability Caused by Relationship Poverty · The Disease of Disconnection and Loneliness · We Must Reconnect

Tenth Conversation: What We Need Now

The order and steps to healing · You can't be anything without taking care of yourself · Learning and growing from trauma

Epilogue

References

Acknowledgements

Detailed image

Into the book

First Conversation: How the Brain Understands the World

What I've learned from talking to countless victims of traumatic events, abuse and neglect, is that after absorbing these painful experiences, children begin to suffer.

There is a deep-seated desire to feel needed, accepted, and valuable.

As they grow up, these children have no idea what they deserve.

--- p.24

When a child experiences abuse, the child's brain associates the abuser's characteristics, such as hair color or speech, or the context of the abuse, such as the music playing in the background, with feelings of fear.

The complex and confusing associations created in this way can influence behavior for a long time.

For example, many years later, you might go to a restaurant and have a panic attack when you see a brown-haired waiter looking down at you and taking your order.

But because there is no persistent cognitive recall, or linear narrative memory, the panic attacks are often felt and interpreted as random events unrelated to previous experiences.

Experiencing trauma at a young age can lead to certain beliefs and behaviors that may last a lifetime.

--- p.44

Second Conversation: Finding Balance to Sustain Life

In my twenties, I first encountered a situation where managing stress was extremely difficult.

It was when I got a job as a reporter and was working 100 hours a week.

I wanted to be a team player, but I felt like I was increasingly out of sync with others.

(...) When I felt my body sending me stress signals, I ignored them and instead consoled myself with the most readily available medicine: food.

The further my life got out of sync, the more I sought solace in silencing those signals.

--- p.62

When parents provide consistent and predictable care, the child's stress response system becomes more flexible.

When the stress response system is activated over a long period of time or in a chaotic manner, as in cases of abuse or neglect, it becomes sensitized and unable to function properly.

--- p.79

When you ask someone, “What happened to you?” you often discover that the person experienced some form of trauma during their development.

Most people who have experienced 'developmental adversity' have chronic dysregulation.

It generally means that you are nervous and anxious.

Sometimes I get so shocked that I feel like I'm going to burst out of my body, and I feel an inner storm, as Russell Brand so well described.

(...) This is because the core control neural network is sensitized.

--- p.83

There is always a need to control, a need to find comfort, a need to fill a reward bucket.

But it turns out that the most powerful rewards are those that come from human relationships.

Positive interactions with people bring us the satisfaction of reward and the stability of control.

Without connections with people who care about you, spend time with you, and support you, it's nearly impossible to break free from harmful reward and conditioning patterns.

--- p.91

Third Conversation: How We Were Loved

Whether it's the President of the United States, the incredible Beyoncé, a mother spilling a painful secret, or a criminal asking for forgiveness, anyone I've ever spoken to has, after an interview, checked my expression to gauge my reaction, asking, "Did I do a good job?"

(...) Everyone has the same desire to be accepted by others and to have their truth confirmed.

Beyond science, I know that this feeling ultimately boils down to 'how you were loved.'

--- p.100~101

Our ability to connect in meaningful and healthy ways is built by our first relationships.

Love and affectionate care are the foundation of development.

--- p.101

Stress is not something to be feared or avoided.

What causes problems is the pattern and intensity of stress, and whether it is controllable.

The sad thing is that so many people have stress activation patterns that are unpredictable, uncontrollable, long-lasting, or extreme.

--- p.113

Fourth Conversation: What We Call Trauma

I believe trauma can also arise from less obvious and quiet events, such as emotional abuse, such as humiliation or shame from parents, or the marginalization of children from minority groups within the majority community.

--- p.137~138

A key finding is that the timing of adversity makes a big difference in determining overall risk.

Simply put, a trauma experienced at age 2 has a greater impact on health than the same trauma experienced at age 17.

--- p.145

If a child has been abused within an intimate relationship (for example, by a parent), the child may come to feel threatened by intimacy, that is, emotional and physical closeness.

These people often take a long time to form connections in relationships, and when they do get close to someone, they feel anxious, confused, or overwhelmed.

You end up avoiding the intimacy that comes from human relationships.

If you can't avoid intimacy, you'll end up doing things that will damage or ruin the relationship.

This is one of the most common and least recognized aspects of the impact of developmental trauma.

--- p.158

This means that countless adults continue to carry these wounds in their daily lives, at work, and in their relationships, passing them on to their children.

And those adults may not have realized what had happened to them.

Not only do they not know what happened, but their partners, doctors, and coworkers also do not know.

That's exactly why so many misunderstandings arise.

--- p.161

Conversation Five: Connecting the Dots

Connecting the dots to finally understand both the cause and effect of my sleep problems was a complete mind-altering experience for me.

I still feel myself reacting to the deep stress points created in my grandmother's bedroom long ago, but now I have the tools to understand the situation, step back, observe what I'm feeling, and choose how to move through that fear.

--- p.166~167

One of the most important ways we pass on 'information' to the next generation is through our genes.

Some aspects of our stress response system are also 'heritable'.

--- p.179

The good news is that the brain is still capable of change.

(...) Just as threats and trauma can cause epigenetic changes, the interplay of good care can reverse those changes.

--- p.181~182

Conversation Six: Moving from Coping to Healing

Why can't I finish what I'm doing when things get difficult? It's because my brain is trained to dissociate when things become uncomfortable or threatening.

Even though a math test isn't as big of a threat as someone trying to harm me, Harry's reactivity is so heightened that he'll react by blocking even to a math test.

--- p.236~237

If you don't notice the pattern, it's very difficult to change it.

The children and adults we worked with were so accustomed to chaos that they actually felt more comfortable in chaos than in calm.

So they were very uncomfortable going into a classroom or a new foster home with people who were predictable, consistent, and thoughtful.

As that discomfort gradually grew and reached a certain limit, they eventually provoked others into reacting in a way they could predict.

--- p.251~253

People think of psychotherapy as going back into something that happened in the past and trying to get it out of the way.

But whatever past experiences have created in our brains, (...) we can't just erase them.

You can't erase the past.

Rather, psychotherapy is more about building new associations and creating new, healthy basic pathways.

It's like driving on a two-lane dirt road and then building a new four-lane highway next to it.

The old road still remains, but it is no longer used as much as it once was.

--- p.255~256

Seventh Conversation: Wisdom from Trauma

We often use the belief that others will be 'resilient' as a shield to protect our emotions.

It's about protecting ourselves from the discomfort, confusion, and helplessness we feel in the face of their trauma.

This is a kind of externalization.

--- p.258~259

For tens of thousands of years, humans lived in small groups made up of several generations.

There were no mental hospitals, but there was a lot of trauma.

I think many of our ancestors suffered from post-traumatic stress disorders such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders.

But at the same time, I think they also experienced healing.

(...) Unfortunately, few modern approaches make good use of all four methods.

The medical model over-focuses on psychopharmacology (④) and cognitive-behavioral approaches (③), while greatly underestimating the value of connectivity (①) and rhythm (②).

--- p.280

Allie's healing power and continued resilience were possible because she had enduring relationships that provided her with safety and security, and through those relationships, she was able to 'make sense' of the horrific events and reframe them within the context of her own belief system.

Even people who seem to have incredible resilience can be depleted by poor relationships, persistent stress, distress, and trauma.

--- p.282

Conversation Eight: Our Brains, Our Biases, Our Systems

I don't think you can truly understand trauma unless you recognize the biases embedded within you and the structural biases in the systems you live in—bias around race, gender, and sexual orientation.

Being marginalized—being excluded, undervalued, and insulted—is traumatic.

--- p.308

Unfortunately, schools (...) tend to prohibit many of the behaviors that help children self-regulate.

This includes actions such as walking or swaying your body back and forth, fiddling with something while listening to class, or listening to music with earphones while doing homework.

(...) We also tend to underestimate the powerful healing and resilience-building activities like sports, music, and art.

(...) In fact, it contains regulatory and relational elements, which can be the most important foundation for academic study.

--- p.318~319

Ninth Conversation: Modern Society's Relationships

In modern life, we have fewer and fewer opportunities to share in relational interactions. (...) As a result, as a population, we have become more self-absorbed, anxious, depressed, and therefore less resilient.

--- p.364~365

One might argue that part of the reason for the rise in anxiety in the modern world is the influx of newness, especially social newness, coupled with the lack of relational connections that could provide a counterbalance.

--- p.374

Tenth Conversation: What We Need Now

Adversity, challenges, disappointments, losses, traumas—all of these things broadly cultivate our capacity to empathize with others and to grow in wisdom.

In some ways, trauma and adversity can be gifts.

What people do with these gifts will vary.

What I've learned from talking to countless victims of traumatic events, abuse and neglect, is that after absorbing these painful experiences, children begin to suffer.

There is a deep-seated desire to feel needed, accepted, and valuable.

As they grow up, these children have no idea what they deserve.

--- p.24

When a child experiences abuse, the child's brain associates the abuser's characteristics, such as hair color or speech, or the context of the abuse, such as the music playing in the background, with feelings of fear.

The complex and confusing associations created in this way can influence behavior for a long time.

For example, many years later, you might go to a restaurant and have a panic attack when you see a brown-haired waiter looking down at you and taking your order.

But because there is no persistent cognitive recall, or linear narrative memory, the panic attacks are often felt and interpreted as random events unrelated to previous experiences.

Experiencing trauma at a young age can lead to certain beliefs and behaviors that may last a lifetime.

--- p.44

Second Conversation: Finding Balance to Sustain Life

In my twenties, I first encountered a situation where managing stress was extremely difficult.

It was when I got a job as a reporter and was working 100 hours a week.

I wanted to be a team player, but I felt like I was increasingly out of sync with others.

(...) When I felt my body sending me stress signals, I ignored them and instead consoled myself with the most readily available medicine: food.

The further my life got out of sync, the more I sought solace in silencing those signals.

--- p.62

When parents provide consistent and predictable care, the child's stress response system becomes more flexible.

When the stress response system is activated over a long period of time or in a chaotic manner, as in cases of abuse or neglect, it becomes sensitized and unable to function properly.

--- p.79

When you ask someone, “What happened to you?” you often discover that the person experienced some form of trauma during their development.

Most people who have experienced 'developmental adversity' have chronic dysregulation.

It generally means that you are nervous and anxious.

Sometimes I get so shocked that I feel like I'm going to burst out of my body, and I feel an inner storm, as Russell Brand so well described.

(...) This is because the core control neural network is sensitized.

--- p.83

There is always a need to control, a need to find comfort, a need to fill a reward bucket.

But it turns out that the most powerful rewards are those that come from human relationships.

Positive interactions with people bring us the satisfaction of reward and the stability of control.

Without connections with people who care about you, spend time with you, and support you, it's nearly impossible to break free from harmful reward and conditioning patterns.

--- p.91

Third Conversation: How We Were Loved

Whether it's the President of the United States, the incredible Beyoncé, a mother spilling a painful secret, or a criminal asking for forgiveness, anyone I've ever spoken to has, after an interview, checked my expression to gauge my reaction, asking, "Did I do a good job?"

(...) Everyone has the same desire to be accepted by others and to have their truth confirmed.

Beyond science, I know that this feeling ultimately boils down to 'how you were loved.'

--- p.100~101

Our ability to connect in meaningful and healthy ways is built by our first relationships.

Love and affectionate care are the foundation of development.

--- p.101

Stress is not something to be feared or avoided.

What causes problems is the pattern and intensity of stress, and whether it is controllable.

The sad thing is that so many people have stress activation patterns that are unpredictable, uncontrollable, long-lasting, or extreme.

--- p.113

Fourth Conversation: What We Call Trauma

I believe trauma can also arise from less obvious and quiet events, such as emotional abuse, such as humiliation or shame from parents, or the marginalization of children from minority groups within the majority community.

--- p.137~138

A key finding is that the timing of adversity makes a big difference in determining overall risk.

Simply put, a trauma experienced at age 2 has a greater impact on health than the same trauma experienced at age 17.

--- p.145

If a child has been abused within an intimate relationship (for example, by a parent), the child may come to feel threatened by intimacy, that is, emotional and physical closeness.

These people often take a long time to form connections in relationships, and when they do get close to someone, they feel anxious, confused, or overwhelmed.

You end up avoiding the intimacy that comes from human relationships.

If you can't avoid intimacy, you'll end up doing things that will damage or ruin the relationship.

This is one of the most common and least recognized aspects of the impact of developmental trauma.

--- p.158

This means that countless adults continue to carry these wounds in their daily lives, at work, and in their relationships, passing them on to their children.

And those adults may not have realized what had happened to them.

Not only do they not know what happened, but their partners, doctors, and coworkers also do not know.

That's exactly why so many misunderstandings arise.

--- p.161

Conversation Five: Connecting the Dots

Connecting the dots to finally understand both the cause and effect of my sleep problems was a complete mind-altering experience for me.

I still feel myself reacting to the deep stress points created in my grandmother's bedroom long ago, but now I have the tools to understand the situation, step back, observe what I'm feeling, and choose how to move through that fear.

--- p.166~167

One of the most important ways we pass on 'information' to the next generation is through our genes.

Some aspects of our stress response system are also 'heritable'.

--- p.179

The good news is that the brain is still capable of change.

(...) Just as threats and trauma can cause epigenetic changes, the interplay of good care can reverse those changes.

--- p.181~182

Conversation Six: Moving from Coping to Healing

Why can't I finish what I'm doing when things get difficult? It's because my brain is trained to dissociate when things become uncomfortable or threatening.

Even though a math test isn't as big of a threat as someone trying to harm me, Harry's reactivity is so heightened that he'll react by blocking even to a math test.

--- p.236~237

If you don't notice the pattern, it's very difficult to change it.

The children and adults we worked with were so accustomed to chaos that they actually felt more comfortable in chaos than in calm.

So they were very uncomfortable going into a classroom or a new foster home with people who were predictable, consistent, and thoughtful.

As that discomfort gradually grew and reached a certain limit, they eventually provoked others into reacting in a way they could predict.

--- p.251~253

People think of psychotherapy as going back into something that happened in the past and trying to get it out of the way.

But whatever past experiences have created in our brains, (...) we can't just erase them.

You can't erase the past.

Rather, psychotherapy is more about building new associations and creating new, healthy basic pathways.

It's like driving on a two-lane dirt road and then building a new four-lane highway next to it.

The old road still remains, but it is no longer used as much as it once was.

--- p.255~256

Seventh Conversation: Wisdom from Trauma

We often use the belief that others will be 'resilient' as a shield to protect our emotions.

It's about protecting ourselves from the discomfort, confusion, and helplessness we feel in the face of their trauma.

This is a kind of externalization.

--- p.258~259

For tens of thousands of years, humans lived in small groups made up of several generations.

There were no mental hospitals, but there was a lot of trauma.

I think many of our ancestors suffered from post-traumatic stress disorders such as anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders.

But at the same time, I think they also experienced healing.

(...) Unfortunately, few modern approaches make good use of all four methods.

The medical model over-focuses on psychopharmacology (④) and cognitive-behavioral approaches (③), while greatly underestimating the value of connectivity (①) and rhythm (②).

--- p.280

Allie's healing power and continued resilience were possible because she had enduring relationships that provided her with safety and security, and through those relationships, she was able to 'make sense' of the horrific events and reframe them within the context of her own belief system.

Even people who seem to have incredible resilience can be depleted by poor relationships, persistent stress, distress, and trauma.

--- p.282

Conversation Eight: Our Brains, Our Biases, Our Systems

I don't think you can truly understand trauma unless you recognize the biases embedded within you and the structural biases in the systems you live in—bias around race, gender, and sexual orientation.

Being marginalized—being excluded, undervalued, and insulted—is traumatic.

--- p.308

Unfortunately, schools (...) tend to prohibit many of the behaviors that help children self-regulate.

This includes actions such as walking or swaying your body back and forth, fiddling with something while listening to class, or listening to music with earphones while doing homework.

(...) We also tend to underestimate the powerful healing and resilience-building activities like sports, music, and art.

(...) In fact, it contains regulatory and relational elements, which can be the most important foundation for academic study.

--- p.318~319

Ninth Conversation: Modern Society's Relationships

In modern life, we have fewer and fewer opportunities to share in relational interactions. (...) As a result, as a population, we have become more self-absorbed, anxious, depressed, and therefore less resilient.

--- p.364~365

One might argue that part of the reason for the rise in anxiety in the modern world is the influx of newness, especially social newness, coupled with the lack of relational connections that could provide a counterbalance.

--- p.374

Tenth Conversation: What We Need Now

Adversity, challenges, disappointments, losses, traumas—all of these things broadly cultivate our capacity to empathize with others and to grow in wisdom.

In some ways, trauma and adversity can be gifts.

What people do with these gifts will vary.

--- p.402

Publisher's Review

The fundamental trauma that permeates our lives

How were you loved or not loved?

A few years ago, Oprah Winfrey spent hours watching TV in her dying mother's room.

I flew a long distance thinking that it might be the last time I would spend with my mother, but the whole time I was alone with her, I couldn't think of anything to say.

Why did the talk show queen, who had spoken to thousands of people, from world-famous stars to politicians and criminals, remain silent in front of her dying mother? What happened between them?

Born to a single mother with no financial means, Winfrey spent the first six years of her life raised by her grandmother as a "battered, smiling child." She then grew up between her estranged parents, never establishing roots with either.

From the earliest days I can remember, I've always felt lonely, never loved, and just a burden to my parents.

For Winfrey, the underlying trauma that permeates all of life's misfortunes boils down to "the feeling of not being loved."

Bruce D. Views Trauma Through the Lens of the Brain and Development

According to Dr. Perry, negative experiences and stresses, both big and small, in childhood can affect us throughout our lives.

Children who do not receive stable affection and care from their parents, and who have even experienced abuse or neglect, are unable to establish standards for their own worth and qualifications.

They suppress their own desires and conform to others, habitually avoid difficult challenges or uncomfortable situations, and have difficulty forming or maintaining relationships with others.

This conformist tendency is a case where the dissociative response, a coping mechanism that appears in people who have experienced unavoidable threats or stress, has developed into a personality trait.

It took Winfrey half a lifetime to overcome this tendency, and her relationship with her mother remained a problem she never fully resolved.

Struggling with a broken heart

A Trauma Guide for Children and Adults

Winfrey's conversation with child psychiatrist Dr. Perry about trauma dates back 30 years.

It was a time when Dr. Perry, a young researcher who had studied brain science and then entered the field of psychiatry, was grappling with childhood trauma, a topic that even his colleagues had little interest in.

The two, who met through Winfrey's initial contact, have shared their intense struggles with trauma and healing from their own perspectives, and this book condenses their 30-year-long conversation into ten chapters.

Their conversation moves toward healing by exploring how trauma works in our brains and bodies (conversations one through three), the diverse experiences of individuals that cause trauma (conversation four), historical trauma that is passed down through generations (conversation five), and how our brains cope with threats (conversation six).

The conversation unfolds in turn: what each of us needs to build resilience (seventh conversation); what needs to be done at the societal level, such as in education and health systems (eighth conversation); how we have become more vulnerable in times of isolation and disconnection (ninth conversation); and how it is possible to transform the wounds of trauma into wisdom (tenth conversation).

It contains various stories of adults and children they met, along with friendly scientific explanations that are easy on the eyes.

These stories, which sometimes overwhelm with shock and sadness, and sometimes make you want to quietly hold their hand, help us understand the complex concepts and theories of brain science and psychiatry with our hearts, not just our heads.

The past that has already happened cannot be changed, but our brain has the flexibility to change at any time.

The authors say there is hope for us all here, guiding readers to find the courage to look within themselves and ultimately discover “the path to healing wounds with one’s own strength” (Jeong Yeo-ul’s recommendation).

“What the hell is wrong with you?”

If you want to find the answer, you have to change the question.

“What happened to you?”

Although the word trauma is widely used and it's no surprise to see celebrities on TV counseling programs talking about their childhood traumas, it's still not easy to recognize our own trauma.

When we are overcome by negative emotions for no reason, when we are unable to change recurring, harmful behavior patterns, or when we cannot identify the cause, we often blame ourselves.

“What the hell is wrong with me?”

Even if you seek out a psychiatrist or counselor to address your issues, focusing only on symptoms and diagnoses will prevent you from addressing the root causes and solutions.

Even if several people have the same diagnosis, the cause may be different for each person.

Thomas and James, twelve-year-olds Dr. Perry met, were both diagnosed with ADHD.

However, the carelessness of Thomas, who grew up under an abusive father and was highly vigilant, and the carelessness of James, who fell into daydreams to escape into his inner world in the chaotic situation of constantly changing caregivers, were completely different.

Accordingly, the treatment methods and progress of the two boys were different.

Dr. Perry says that before diagnosing people and prescribing treatments, we need to look at each person's life history to see if there were any events that affected their brain while they were growing up and living, and if there were any relationships that served as a safety net to prevent them from completely falling apart when faced with adversity and stress.

This is why I strongly believe that this book should shift the question to, “What happened to you?”

By asking this question, we can find the cause and answer to the problem without blaming others for their actions and problems in their hearts, and thereby save ourselves and our loved ones from the hellish state of mind.

A body that hurts for no reason, a brain that falls into anxiety and fear

People who have suffered trauma live in the present, but their brains are stuck in the past.

The brain, which has adapted to deal with certain threats or stresses, cannot escape from the past state even after the situation is over.

Examples include Mr. Roseman, who screamed as if he were transported back to the trenches of the Korean War the moment he heard the sound of a motorcycle engine, and Sam, who unconsciously felt a sense of rejection towards a teacher who smelled like the cosmetics of his abusive father.

They have in common a sensitized stress response system affected by trauma.

Even minor things can easily cause the brain to feel anxious and fearful, triggering coping responses such as arousal or dissociation.

As a result, people who seem to others to explode with emotions or cause problem behavior for no reason or over trivial things.

The impact of trauma does not stop at these psychological realms.

Trauma can actually threaten our physical health.

Chronic abdominal pain, headaches, and cramps are common symptoms experienced by people with developmental trauma, and research has shown that childhood adversity increases the risk of all kinds of health problems.

The key to building resilience is connectivity.

How can healing, the process of correcting a misaligned system and restoring balance between body and mind, be achieved? The most important tool for healing presented in this book is connection—our relationships with others.

In particular, the love we receive as children becomes the foundation for developing resilience.

Eleven-year-old Kate says sharing a bowl of cereal with her dying mother at 2 a.m. was the best moment of the months she spent with her dying mother.

Such moments of complete connection are often trivial and everyday.

That brief but powerful moment is said to have been a great source of strength for Kate as she went through the painful times of losing her mother.

The inside of a traumatized person is like a shipwreck.

To mend a broken heart, we must revisit the scene of the shipwreck, examine the shattered fragments, and move some of them to a new, safe haven in the present.

Through this process of recalling and reprocessing traumatic experiences, our internal systems slowly 'reset'.

Ideally, we would experience hundreds or thousands of these brief moments of healing in relationships with people who support us and are fully present with us.

Winfrey and her friend Gayle King were each other's therapists.

Winfrey had never received professional trauma therapy, but daily open conversations with King gave her the strength to heal her own wounds.

“We were all once wounded children.”

The journey to recovery from trauma can be slow and painful, but it can also be a process of developing your own strengths and capabilities.

For those who have survived adversity, there comes a time in life when they can look back on that experience, learn from it, and grow.

Oprah, who was returning home without saying a word to her mother in what might be her last meeting, finally mustered up the courage to turn around.

And in front of my mother, I finally said what I had been preparing for a long time.

He said he was “okay.”

“So now you know I’m okay and you can leave.”

To free her mother from the guilt of her past, Oprah first freed herself from painful memories and emotions.

The authors hope that those struggling with broken hearts will read this book and tell themselves, "It's okay."

Sometimes offering tender comfort, sometimes offering sober scientific advice, this book will be an essential guide for anyone seeking to understand, let go of, and finally move forward from what has happened to them.

How were you loved or not loved?

A few years ago, Oprah Winfrey spent hours watching TV in her dying mother's room.

I flew a long distance thinking that it might be the last time I would spend with my mother, but the whole time I was alone with her, I couldn't think of anything to say.

Why did the talk show queen, who had spoken to thousands of people, from world-famous stars to politicians and criminals, remain silent in front of her dying mother? What happened between them?

Born to a single mother with no financial means, Winfrey spent the first six years of her life raised by her grandmother as a "battered, smiling child." She then grew up between her estranged parents, never establishing roots with either.

From the earliest days I can remember, I've always felt lonely, never loved, and just a burden to my parents.

For Winfrey, the underlying trauma that permeates all of life's misfortunes boils down to "the feeling of not being loved."

Bruce D. Views Trauma Through the Lens of the Brain and Development

According to Dr. Perry, negative experiences and stresses, both big and small, in childhood can affect us throughout our lives.

Children who do not receive stable affection and care from their parents, and who have even experienced abuse or neglect, are unable to establish standards for their own worth and qualifications.

They suppress their own desires and conform to others, habitually avoid difficult challenges or uncomfortable situations, and have difficulty forming or maintaining relationships with others.

This conformist tendency is a case where the dissociative response, a coping mechanism that appears in people who have experienced unavoidable threats or stress, has developed into a personality trait.

It took Winfrey half a lifetime to overcome this tendency, and her relationship with her mother remained a problem she never fully resolved.

Struggling with a broken heart

A Trauma Guide for Children and Adults

Winfrey's conversation with child psychiatrist Dr. Perry about trauma dates back 30 years.

It was a time when Dr. Perry, a young researcher who had studied brain science and then entered the field of psychiatry, was grappling with childhood trauma, a topic that even his colleagues had little interest in.

The two, who met through Winfrey's initial contact, have shared their intense struggles with trauma and healing from their own perspectives, and this book condenses their 30-year-long conversation into ten chapters.

Their conversation moves toward healing by exploring how trauma works in our brains and bodies (conversations one through three), the diverse experiences of individuals that cause trauma (conversation four), historical trauma that is passed down through generations (conversation five), and how our brains cope with threats (conversation six).

The conversation unfolds in turn: what each of us needs to build resilience (seventh conversation); what needs to be done at the societal level, such as in education and health systems (eighth conversation); how we have become more vulnerable in times of isolation and disconnection (ninth conversation); and how it is possible to transform the wounds of trauma into wisdom (tenth conversation).

It contains various stories of adults and children they met, along with friendly scientific explanations that are easy on the eyes.

These stories, which sometimes overwhelm with shock and sadness, and sometimes make you want to quietly hold their hand, help us understand the complex concepts and theories of brain science and psychiatry with our hearts, not just our heads.

The past that has already happened cannot be changed, but our brain has the flexibility to change at any time.

The authors say there is hope for us all here, guiding readers to find the courage to look within themselves and ultimately discover “the path to healing wounds with one’s own strength” (Jeong Yeo-ul’s recommendation).

“What the hell is wrong with you?”

If you want to find the answer, you have to change the question.

“What happened to you?”

Although the word trauma is widely used and it's no surprise to see celebrities on TV counseling programs talking about their childhood traumas, it's still not easy to recognize our own trauma.

When we are overcome by negative emotions for no reason, when we are unable to change recurring, harmful behavior patterns, or when we cannot identify the cause, we often blame ourselves.

“What the hell is wrong with me?”

Even if you seek out a psychiatrist or counselor to address your issues, focusing only on symptoms and diagnoses will prevent you from addressing the root causes and solutions.

Even if several people have the same diagnosis, the cause may be different for each person.

Thomas and James, twelve-year-olds Dr. Perry met, were both diagnosed with ADHD.

However, the carelessness of Thomas, who grew up under an abusive father and was highly vigilant, and the carelessness of James, who fell into daydreams to escape into his inner world in the chaotic situation of constantly changing caregivers, were completely different.

Accordingly, the treatment methods and progress of the two boys were different.

Dr. Perry says that before diagnosing people and prescribing treatments, we need to look at each person's life history to see if there were any events that affected their brain while they were growing up and living, and if there were any relationships that served as a safety net to prevent them from completely falling apart when faced with adversity and stress.

This is why I strongly believe that this book should shift the question to, “What happened to you?”

By asking this question, we can find the cause and answer to the problem without blaming others for their actions and problems in their hearts, and thereby save ourselves and our loved ones from the hellish state of mind.

A body that hurts for no reason, a brain that falls into anxiety and fear

People who have suffered trauma live in the present, but their brains are stuck in the past.

The brain, which has adapted to deal with certain threats or stresses, cannot escape from the past state even after the situation is over.

Examples include Mr. Roseman, who screamed as if he were transported back to the trenches of the Korean War the moment he heard the sound of a motorcycle engine, and Sam, who unconsciously felt a sense of rejection towards a teacher who smelled like the cosmetics of his abusive father.

They have in common a sensitized stress response system affected by trauma.

Even minor things can easily cause the brain to feel anxious and fearful, triggering coping responses such as arousal or dissociation.

As a result, people who seem to others to explode with emotions or cause problem behavior for no reason or over trivial things.

The impact of trauma does not stop at these psychological realms.

Trauma can actually threaten our physical health.

Chronic abdominal pain, headaches, and cramps are common symptoms experienced by people with developmental trauma, and research has shown that childhood adversity increases the risk of all kinds of health problems.

The key to building resilience is connectivity.

How can healing, the process of correcting a misaligned system and restoring balance between body and mind, be achieved? The most important tool for healing presented in this book is connection—our relationships with others.

In particular, the love we receive as children becomes the foundation for developing resilience.

Eleven-year-old Kate says sharing a bowl of cereal with her dying mother at 2 a.m. was the best moment of the months she spent with her dying mother.

Such moments of complete connection are often trivial and everyday.

That brief but powerful moment is said to have been a great source of strength for Kate as she went through the painful times of losing her mother.

The inside of a traumatized person is like a shipwreck.

To mend a broken heart, we must revisit the scene of the shipwreck, examine the shattered fragments, and move some of them to a new, safe haven in the present.

Through this process of recalling and reprocessing traumatic experiences, our internal systems slowly 'reset'.

Ideally, we would experience hundreds or thousands of these brief moments of healing in relationships with people who support us and are fully present with us.

Winfrey and her friend Gayle King were each other's therapists.

Winfrey had never received professional trauma therapy, but daily open conversations with King gave her the strength to heal her own wounds.

“We were all once wounded children.”

The journey to recovery from trauma can be slow and painful, but it can also be a process of developing your own strengths and capabilities.

For those who have survived adversity, there comes a time in life when they can look back on that experience, learn from it, and grow.

Oprah, who was returning home without saying a word to her mother in what might be her last meeting, finally mustered up the courage to turn around.

And in front of my mother, I finally said what I had been preparing for a long time.

He said he was “okay.”

“So now you know I’m okay and you can leave.”

To free her mother from the guilt of her past, Oprah first freed herself from painful memories and emotions.

The authors hope that those struggling with broken hearts will read this book and tell themselves, "It's okay."

Sometimes offering tender comfort, sometimes offering sober scientific advice, this book will be an essential guide for anyone seeking to understand, let go of, and finally move forward from what has happened to them.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: April 26, 2022

- Page count, weight, size: 424 pages | 534g | 140*210*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788960519176

- ISBN10: 8960519170

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)