Seeing the forest from the trees

|

Description

Book Introduction

A realistic and concise account of a museum of living time

Richard Forty's Grimdike Forest Project

“In this small forest, I enjoyed the pleasure of observing and recording for a year.”

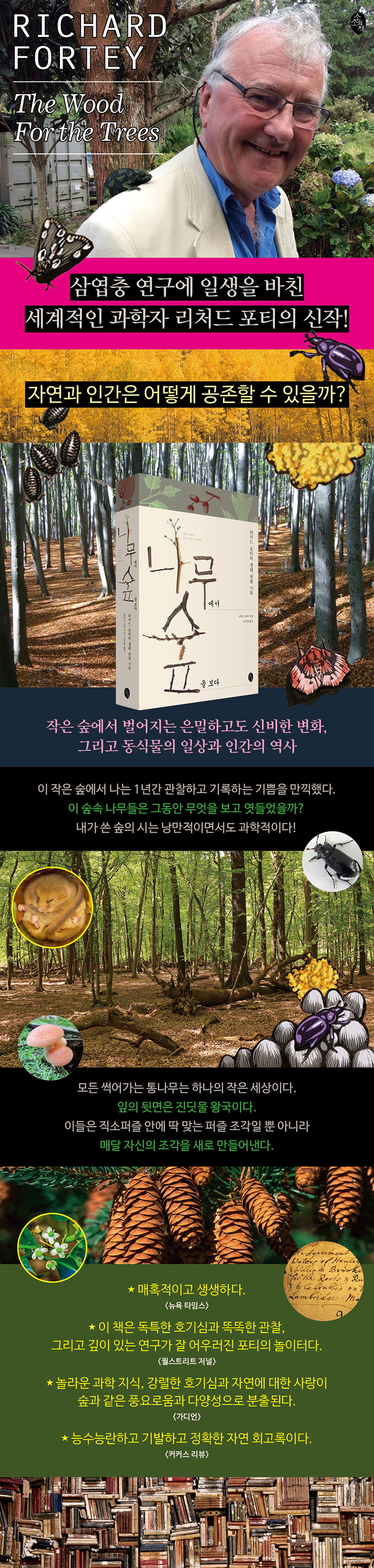

Richard Forty, a senior paleontologist and science writer at the Natural History Museum in London, is a naturalist who believes that all life is as interesting as humans.

Having spent his life in museums, handling fossils of extinct animals, this time he headed to the forest, a realm of coexistence between nature and humans, to explore various plants, animals, and living creatures.

This book is the result of his own exploration and observation of his own forest, along with forest-related materials and the assistance of experts.

He describes the forest's fundamental flora and fauna, the changing seasons, visits from enthusiastic companions, the play of light among the branches, the influence of geology, and how the forest has shaped history, architecture, and industry.

On every page, he demonstrates how a detailed study of a small forest can reveal countless facts about the natural world, and he recounts his own delight in the incomparable joy of discovery.

Richard Forty, a scientist who has studied trilobites for 30 years and is well known to domestic readers, purchased a 5,000-pyeong beech-bluebell forest after retiring from the museum.

Soon he began to record his observations and discoveries in a small leather notebook, which soon became a biographies of the forest.

This book illuminates from various angles not only the ever-changing diversity of the natural world, but also the relationship between forests, with their history spanning over 1,000 years, and humans to this day.

In the past, forests were inevitably closely linked to the wider world of commerce and markets.

The ancient manor decided the fate of the forest for centuries.

The appearance of the forest has also changed according to human needs.

Today, forests are valued more as attractive backdrops or scenic views than as productive resources for people.

The fate of the tree was the same.

Before the industrial age, life without oak trees was unimaginable.

Oak was an essential material for those who made wooden barrels and cart wheels.

When building a ship, the only material that could support the captain's cabin and provide splendid decoration was oak.

The oak was an irreplaceable resource, a tree imbued with the virtues of trust and patience.

After that golden age, the oak was deified in literature, but its utility as a profitable resource was lost.

Yet the old oak tree still stands there.

To cover both natural and human history in this book, Forty had to search for archaeological sites that are over 2,000 years old and study the long history of forests, from the making of wooden furniture to the making of tent pegs.

It also traces old objects forgotten from people's memories and how people lived at that time.

You can make bowls and collectibles from trees cut in your own forest, and experience the charcoal-making process.

I imagine what historical events the trees in the forest have witnessed, what secret conversations they have overheard, and who might be hiding beneath the trees.

We will explore the archaeological remains of ancient structures in a long drainage ditch stretching along the edge of the forest and discover whether forests can provide humans with not only spiritual inspiration but also physical fulfillment.

In this book, Poti, who is meticulous and does not overlook anything, fully displays his literary talent along with his scientist's unique temperament.

Sometimes he speaks cynically, but he also whispers his own recipes using mushrooms, berries, and wild greens that can be found in the forest.

Collect moss, lichen, grass, insects, etc., and examine all the trees in the forest, including beech, oak, ash, and yew.

On moonlit nights, I catch moths, and during the day, I chase them around here and there, carrying a net to catch crickets.

I dig up rotten logs to examine the decay process, and I poke, prod, and sniff the base of each strawberry bush.

Tiles are made from forest clay and quartz pebbles are melted to create green glass.

He listens to the breathing of the forest without any interference from anyone in his forest, and brings out the colorful stories of those who made the forest their home or had a connection with the forest.

Richard Forty's Grimdike Forest Project

“In this small forest, I enjoyed the pleasure of observing and recording for a year.”

Richard Forty, a senior paleontologist and science writer at the Natural History Museum in London, is a naturalist who believes that all life is as interesting as humans.

Having spent his life in museums, handling fossils of extinct animals, this time he headed to the forest, a realm of coexistence between nature and humans, to explore various plants, animals, and living creatures.

This book is the result of his own exploration and observation of his own forest, along with forest-related materials and the assistance of experts.

He describes the forest's fundamental flora and fauna, the changing seasons, visits from enthusiastic companions, the play of light among the branches, the influence of geology, and how the forest has shaped history, architecture, and industry.

On every page, he demonstrates how a detailed study of a small forest can reveal countless facts about the natural world, and he recounts his own delight in the incomparable joy of discovery.

Richard Forty, a scientist who has studied trilobites for 30 years and is well known to domestic readers, purchased a 5,000-pyeong beech-bluebell forest after retiring from the museum.

Soon he began to record his observations and discoveries in a small leather notebook, which soon became a biographies of the forest.

This book illuminates from various angles not only the ever-changing diversity of the natural world, but also the relationship between forests, with their history spanning over 1,000 years, and humans to this day.

In the past, forests were inevitably closely linked to the wider world of commerce and markets.

The ancient manor decided the fate of the forest for centuries.

The appearance of the forest has also changed according to human needs.

Today, forests are valued more as attractive backdrops or scenic views than as productive resources for people.

The fate of the tree was the same.

Before the industrial age, life without oak trees was unimaginable.

Oak was an essential material for those who made wooden barrels and cart wheels.

When building a ship, the only material that could support the captain's cabin and provide splendid decoration was oak.

The oak was an irreplaceable resource, a tree imbued with the virtues of trust and patience.

After that golden age, the oak was deified in literature, but its utility as a profitable resource was lost.

Yet the old oak tree still stands there.

To cover both natural and human history in this book, Forty had to search for archaeological sites that are over 2,000 years old and study the long history of forests, from the making of wooden furniture to the making of tent pegs.

It also traces old objects forgotten from people's memories and how people lived at that time.

You can make bowls and collectibles from trees cut in your own forest, and experience the charcoal-making process.

I imagine what historical events the trees in the forest have witnessed, what secret conversations they have overheard, and who might be hiding beneath the trees.

We will explore the archaeological remains of ancient structures in a long drainage ditch stretching along the edge of the forest and discover whether forests can provide humans with not only spiritual inspiration but also physical fulfillment.

In this book, Poti, who is meticulous and does not overlook anything, fully displays his literary talent along with his scientist's unique temperament.

Sometimes he speaks cynically, but he also whispers his own recipes using mushrooms, berries, and wild greens that can be found in the forest.

Collect moss, lichen, grass, insects, etc., and examine all the trees in the forest, including beech, oak, ash, and yew.

On moonlit nights, I catch moths, and during the day, I chase them around here and there, carrying a net to catch crickets.

I dig up rotten logs to examine the decay process, and I poke, prod, and sniff the base of each strawberry bush.

Tiles are made from forest clay and quartz pebbles are melted to create green glass.

He listens to the breathing of the forest without any interference from anyone in his forest, and brings out the colorful stories of those who made the forest their home or had a connection with the forest.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

april

Starting the Project | April's Bluebell Sea | Chiltern Hills and a Dot of Peace | Lambridgewood and its Connection to the Darwin Family | Cherry Blossoms and Tutu | Spring Symphony Orchestra | Wild Minari Soup

May

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde | The First Logging | The Spring Forest Scent Expert | The Shameless Writer Who Came to Live in the Countryside | The Stranger in the Forest, or rather, Lee Bang-seok | The Old Maid and the Geranium | The Party Bugle Blown by the Ferns | The Elegance of Spring with Beech Wine | Guessing the Name of the Bat by the Inaudible Sound

June

The Story Behind the Moth's Name | Guessing the Age of the Beech Tree | The Wicked Squirrel | Ghosts and a Love Triangle | Climbing Through the Forest Canopy | Revenge on the Nettle | Making Fertilizer

July

A spooky rainy walk | The Devil's ruins and treasured gold coins | The windless yew tree | Deer and dog | Under the sun | Wild cherry jam

August

Why aren't there many snails in our forest? | The Horned God | In Search of the Origins of Grimdike Forest | The Immortal Forest That Defies Time | Bricks and Stones | Experience the Stone Age

September

Gold and Perfect Design | Mansions and Cities | Oak Trees | Truffles | Daddy-Long-Legs | Braised Mushrooms and Potatoes

october

The Arms Race with the Beech Tree | The Grays Court People | The Mushroom Gallery | The Elm Story | Spiders, Experts in Traps and Cunning

November

Small Gunshots and Pheasants | Big Gunshots and the Estate Manager | Drama in the Dark World Under the Log | Chills and Seizures on Earth | My Hobby is Deer Poop Cultivation

december

Frosty Morning | Holly and Noah's Ark | Slavery | Highwaymen and Turnpikes | Cooperation in the Trees

january

The Second Logging | The Chair That Saved the Forest | The Bridgemaker and the Turner | Wooden Bowls | The Miraculous Sound That Opened a New Era | Henry Royal Regatta | Snow

february

Moss expert, Napsiyo|The last person in the dark age of the beech tree|The last spell|Blow, wind, so that your cheeks are torn|Charcoal

March

An Early Spring Windfall | The Land of the People | Beetles | The Future of the Forest | An Apology to All Small Creatures | Starting Again | The Completed Curiosity Box

Acknowledgments | Translator's Note | Notes | List of Illustrations | Index

Starting the Project | April's Bluebell Sea | Chiltern Hills and a Dot of Peace | Lambridgewood and its Connection to the Darwin Family | Cherry Blossoms and Tutu | Spring Symphony Orchestra | Wild Minari Soup

May

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde | The First Logging | The Spring Forest Scent Expert | The Shameless Writer Who Came to Live in the Countryside | The Stranger in the Forest, or rather, Lee Bang-seok | The Old Maid and the Geranium | The Party Bugle Blown by the Ferns | The Elegance of Spring with Beech Wine | Guessing the Name of the Bat by the Inaudible Sound

June

The Story Behind the Moth's Name | Guessing the Age of the Beech Tree | The Wicked Squirrel | Ghosts and a Love Triangle | Climbing Through the Forest Canopy | Revenge on the Nettle | Making Fertilizer

July

A spooky rainy walk | The Devil's ruins and treasured gold coins | The windless yew tree | Deer and dog | Under the sun | Wild cherry jam

August

Why aren't there many snails in our forest? | The Horned God | In Search of the Origins of Grimdike Forest | The Immortal Forest That Defies Time | Bricks and Stones | Experience the Stone Age

September

Gold and Perfect Design | Mansions and Cities | Oak Trees | Truffles | Daddy-Long-Legs | Braised Mushrooms and Potatoes

october

The Arms Race with the Beech Tree | The Grays Court People | The Mushroom Gallery | The Elm Story | Spiders, Experts in Traps and Cunning

November

Small Gunshots and Pheasants | Big Gunshots and the Estate Manager | Drama in the Dark World Under the Log | Chills and Seizures on Earth | My Hobby is Deer Poop Cultivation

december

Frosty Morning | Holly and Noah's Ark | Slavery | Highwaymen and Turnpikes | Cooperation in the Trees

january

The Second Logging | The Chair That Saved the Forest | The Bridgemaker and the Turner | Wooden Bowls | The Miraculous Sound That Opened a New Era | Henry Royal Regatta | Snow

february

Moss expert, Napsiyo|The last person in the dark age of the beech tree|The last spell|Blow, wind, so that your cheeks are torn|Charcoal

March

An Early Spring Windfall | The Land of the People | Beetles | The Future of the Forest | An Apology to All Small Creatures | Starting Again | The Completed Curiosity Box

Acknowledgments | Translator's Note | Notes | List of Illustrations | Index

Detailed image

Into the book

The soul of a sleeping scientist was reawakened as he explored how plants and animals cooperate to form a rich ecosystem.

I collected everything from moss, lichen, grass, insects, and mushrooms.

We also surveyed all the trees in the forest, including beech, oak, ash, and yew.

On moonlit nights, I would catch moths, and during the day, I would play with insect nets and catch crickets.

I dug up rotten logs to examine the decay process, and I poked and prodded and sniffed under each strawberry bush.

I wanted to sublimate the geology of the forest into tiles and glass.

People usually think that the landscape does not change.

But the forest told me that the landscape was always changing.

Finally, the Grimdike Forest became a project.

---From "Starting the April Project"

After hearing about the twists and turns surrounding the ghost orchid, I decided to thoroughly search the forest of Grimdike in June.

I wondered what I could expect from this small patch of land, but I still carefully examined each ditch, densely packed with beech trees.

I won't miss a single one.

I walked up and down, up and down again, for 30 minutes like a zombie who majored in botany.

For a moment, my heart stopped.

Flowers were hanging from yellow stems that rose from the ground.

There were no leaves, no green of any kind.

Is this me? The stem tip was bent like a shepherd's crook, and the clusters of five or six yellow flowers resembled bluebell inflorescences.

But this flower was shaped like a trap.

There is no known orchid that looks like this.

Of course, it wasn't a ghost.

Still, I felt a thrill as if I had seen an unfamiliar welcome.

The Red Data List is a list of the most precious and rare plant species in Britain.

One of them is in our forest! ---From "June - Ghosts, and a Love Triangle"

I don't know why so many people are skeptical about fungi.

Is it simply because they appear out of nowhere? Or because some of them are highly toxic? Perhaps it's because fungi are associated with decay and decay processes.

Like a rotten apple covered in green powder and gray dust clumps on a piece of bread shoved in a corner.

However, plants that are not entangled with fungi cannot grow healthily.

Without scavenging organisms, cellulose and lignin would consume the world.

If it weren't for fungal antibiotics, gangrene would still be a terrible curse today, just as it was for the Nolis family in the past.

I found a shiny orange-brown brown ink mushroom (Coprinellus micaceus) in the forest that someone had trampled underfoot.

It seemed as if a passerby had deliberately crushed it, as if condemning a criminal.

I can't find anything wrong with this mushroom, other than the fact that it's strangely beautiful.

---From "October - Mushroom Gallery"

What I'm taking home today is 'poop'.

Like a rotten log, poop is a special habitat for someone.

These are all part of our forest biodiversity, providing habitat for species that particularly love nitrogen.

Feces reproduce the chain of events in the ecosystem in miniature.

Because, like dignitaries appearing in a market street parade, one species follows the other in a set order.

This parade is always better to watch at home than to go out and see it every time.

Be careful not to let the stool dry out, but also not let it get soaked.

The best way is to put about five pieces of fresh dung in a clear bottle, such as an olive bottle, and add some wet moss to increase the relative humidity.

And then you just open the lid every few days and examine it with a large magnifying glass.

---From "November - My hobby is deer dung cultivation"

The wheel of seasons turns and turns again.

Even in the midst of timelessness, we realize that there is nothing in the forest untouched by history.

This ancient land is inextricably intertwined with human use, and economic necessity, no less than afforestation or squirrel farming, has shaped the forest's shape.

Even the atmosphere carries subtle influences from afar.

If climate change accelerates, the long reign of the beech tree will eventually come to an end.

Regardless of my personal likes and dislikes, this little forest is a very small part of the unified world, and has become increasingly so since the de Grey era.

I dread the thought that our perfect Chiltern Hills beech trees will retreat into the damp bastions as prophesied in ??New Silva??.

But we must accept the fact that nothing lasts forever.

Even this forest with a deep history.

I collected everything from moss, lichen, grass, insects, and mushrooms.

We also surveyed all the trees in the forest, including beech, oak, ash, and yew.

On moonlit nights, I would catch moths, and during the day, I would play with insect nets and catch crickets.

I dug up rotten logs to examine the decay process, and I poked and prodded and sniffed under each strawberry bush.

I wanted to sublimate the geology of the forest into tiles and glass.

People usually think that the landscape does not change.

But the forest told me that the landscape was always changing.

Finally, the Grimdike Forest became a project.

---From "Starting the April Project"

After hearing about the twists and turns surrounding the ghost orchid, I decided to thoroughly search the forest of Grimdike in June.

I wondered what I could expect from this small patch of land, but I still carefully examined each ditch, densely packed with beech trees.

I won't miss a single one.

I walked up and down, up and down again, for 30 minutes like a zombie who majored in botany.

For a moment, my heart stopped.

Flowers were hanging from yellow stems that rose from the ground.

There were no leaves, no green of any kind.

Is this me? The stem tip was bent like a shepherd's crook, and the clusters of five or six yellow flowers resembled bluebell inflorescences.

But this flower was shaped like a trap.

There is no known orchid that looks like this.

Of course, it wasn't a ghost.

Still, I felt a thrill as if I had seen an unfamiliar welcome.

The Red Data List is a list of the most precious and rare plant species in Britain.

One of them is in our forest! ---From "June - Ghosts, and a Love Triangle"

I don't know why so many people are skeptical about fungi.

Is it simply because they appear out of nowhere? Or because some of them are highly toxic? Perhaps it's because fungi are associated with decay and decay processes.

Like a rotten apple covered in green powder and gray dust clumps on a piece of bread shoved in a corner.

However, plants that are not entangled with fungi cannot grow healthily.

Without scavenging organisms, cellulose and lignin would consume the world.

If it weren't for fungal antibiotics, gangrene would still be a terrible curse today, just as it was for the Nolis family in the past.

I found a shiny orange-brown brown ink mushroom (Coprinellus micaceus) in the forest that someone had trampled underfoot.

It seemed as if a passerby had deliberately crushed it, as if condemning a criminal.

I can't find anything wrong with this mushroom, other than the fact that it's strangely beautiful.

---From "October - Mushroom Gallery"

What I'm taking home today is 'poop'.

Like a rotten log, poop is a special habitat for someone.

These are all part of our forest biodiversity, providing habitat for species that particularly love nitrogen.

Feces reproduce the chain of events in the ecosystem in miniature.

Because, like dignitaries appearing in a market street parade, one species follows the other in a set order.

This parade is always better to watch at home than to go out and see it every time.

Be careful not to let the stool dry out, but also not let it get soaked.

The best way is to put about five pieces of fresh dung in a clear bottle, such as an olive bottle, and add some wet moss to increase the relative humidity.

And then you just open the lid every few days and examine it with a large magnifying glass.

---From "November - My hobby is deer dung cultivation"

The wheel of seasons turns and turns again.

Even in the midst of timelessness, we realize that there is nothing in the forest untouched by history.

This ancient land is inextricably intertwined with human use, and economic necessity, no less than afforestation or squirrel farming, has shaped the forest's shape.

Even the atmosphere carries subtle influences from afar.

If climate change accelerates, the long reign of the beech tree will eventually come to an end.

Regardless of my personal likes and dislikes, this little forest is a very small part of the unified world, and has become increasingly so since the de Grey era.

I dread the thought that our perfect Chiltern Hills beech trees will retreat into the damp bastions as prophesied in ??New Silva??.

But we must accept the fact that nothing lasts forever.

Even this forest with a deep history.

---From "March - Starting Again"

Publisher's Review

The curiosity and passion of a scientist blends with nature.

Showing their own small, precious, and mysterious world!

“Maybe I just wanted to be a boy again.”

Richard Forty, from famous scientist to owner of a small forest.

He set himself the challenge of completing a list of the species that inhabit his forest.

It begins in April, when spring flowers embrace warmth and light in the shallow soil where sunlight reaches.

Bluebells transform the beech forest floor into a pretty skirt of flowers in clusters, and the cherry trees unfold a feast of white blossoms at the forest canopy.

Birds suddenly burst into song throughout the forest in search of mates.

In the forests of May, where it has rained for several days, the spurge blooms with unique flowers.

The story of the writer and philosopher who suddenly appeared like this plant, and Miss Stapleton who bloomed with enchanting and vivid red flowers, stimulates the imagination like the pleasant breeze of spring.

In June, when darkness falls, moths, each with its own unique appearance and complex story, are captured by the light, and before the forest sky is covered with green leaves, beech seedlings full of hope sprout here and there in the fallen leaves.

The squirrels that damage beech trees are at their most active these days, and the twists and turns surrounding Britain's rarest plant, the ghost orchid, tempt you to scour the forest.

The forest in July is dark and gloomy because the sunlight does not reach it.

Although no trace of the ancient primeval forest remains, the gaze may recall a mysterious era, and the sight of a deer hopping through a raspberry bush brings to mind the fate of the forest mammals that must have changed over time.

In August, after the thunder and lightning, mushrooms begin to emerge and the competition among trees to grow against the clock becomes fierce.

We look back at how tiles, bricks, and chalk quarried from the chalk beds, which reveal the unique identity of the forest soil, were used in earlier times.

Under the golden September sun, wildflowers nearing the end of their lives spread their tiny seeds.

The adjacent mansions and cities grew up taking advantage of the forests and rivers, and trees were an essential part of the local economy.

Around this time of year, you can find precious truffles underground and observe the flying magpies that flutter like confetti in the air.

In October, the chestnut trees are full of fruit.

It's the time of year when you can explore the colorful mushrooms exploding throughout the forest, and spiders, seemingly under the guidance of a geometer, are busy building their nests for their final hunt.

In November, when frost falls and leaves fall, we reflect on the changing times of humanity centered around the forest and look into the world hidden beneath the rotten logs.

And we also investigate the mysterious forms of life that emerge and change within the deer droppings we collect in the forest.

In December, when ice grows on every branch, walking sticks are made from holly.

Even in the 18th and 19th centuries, people still exploited the forests, and due to poor road conditions, the forests became hideouts for highway robbers.

Lichens that clothe bare trees are like eternal sentinels warning of impending unseen change.

In January, I plan to make a collection box out of the cherry trees I felled.

And I also imagine the hardships of the sawmills, chair makers, and lathe workers who once worked in the forest.

Later, as we entered the industrial age, railroads were built and rowing competitions were held on rivers near cities, forests also took on new roles.

In February, when the trees in the forest are in hibernation, I go out in search of moss plants with a moss guide.

We read about the past from beer bottles found in the forest, and we also make charcoal, which has provided strong firepower for a long time.

In March, when the forest orchestra plays, we discover a dormouse nest and add to the story of the most diverse beetle on Earth.

I believe that forests must continue to be managed in the future, and that the countless creatures that live within them are all precious in their own right.

Beyond pure science and respect for life

A book that shows how nature and humans can coexist

“The forest poem I wrote is romantic yet scientific!”

This book is not just a simple forest story.

As a scientist, he does not stay in the realm of observation or thinking in order to be faithful to his role.

The author, Richard Forty, wanders freely and unconventionally, and does not hesitate to seek expert help when it comes to things in the forest that are beyond his own understanding.

Of course, the record is extremely detailed and not glossed over.

Readers of this book may be surprised to discover that so many living creatures live in forests, parks, or even beneath rotting tree stumps that they pass by without a second thought.

Even fungi, which require a microscope to observe at the molecular level, are not so far removed from us, and it is fascinating to look into what goes on in their world.

The setting of this book is Grimdike, a small forest near London, England.

Here, the author observes and experiences various things.

Sometimes through the eyes of a scientist, sometimes with the curiosity of a fourteen-year-old boy.

When researching and identifying related materials and documents, do not guess but always get confirmation from an expert.

And he records and organizes it in detail in his own way.

In addition, when he describes his daily life, thoughts, or the characteristic scenery of the forest that changes with the seasons, he transforms into a literary writer.

They make alcohol using ingredients from the forest, add unique flavors, and even make jam.

However, even within the same species, there are cases where they are called by different names, and cases where they are different species but are called by the same name.

To minimize such confusion, the plants, animals, and fungi mentioned in this book are given their common names, and the names used on government websites are used with preference.

In cases where there is no Korean name, the English name is used, and for plants, animals, and fungi with unclear names, the Latin scientific name is given and written in italics.

For reference, you can go to the website 'http://www.british-birdsongs.uk' and search for the scientific name of the bird mentioned in this book to hear the song of that bird.

The author also presents a gloomy outlook that if climate change accelerates on Earth, forests will also disappear.

In fact, humans are only a very small part of the natural world, and it is unclear how long they will reign as rulers of this Earth.

All organisms are as interesting as humans, and no less important than the observer.

When I think like that, I feel a sense of fear and my attitude towards nature inevitably changes.

Readers will be able to glimpse the future of nature and humanity in Richard Forty's delightful and joyful tale of forest life, which began to satisfy his own curiosity.

Showing their own small, precious, and mysterious world!

“Maybe I just wanted to be a boy again.”

Richard Forty, from famous scientist to owner of a small forest.

He set himself the challenge of completing a list of the species that inhabit his forest.

It begins in April, when spring flowers embrace warmth and light in the shallow soil where sunlight reaches.

Bluebells transform the beech forest floor into a pretty skirt of flowers in clusters, and the cherry trees unfold a feast of white blossoms at the forest canopy.

Birds suddenly burst into song throughout the forest in search of mates.

In the forests of May, where it has rained for several days, the spurge blooms with unique flowers.

The story of the writer and philosopher who suddenly appeared like this plant, and Miss Stapleton who bloomed with enchanting and vivid red flowers, stimulates the imagination like the pleasant breeze of spring.

In June, when darkness falls, moths, each with its own unique appearance and complex story, are captured by the light, and before the forest sky is covered with green leaves, beech seedlings full of hope sprout here and there in the fallen leaves.

The squirrels that damage beech trees are at their most active these days, and the twists and turns surrounding Britain's rarest plant, the ghost orchid, tempt you to scour the forest.

The forest in July is dark and gloomy because the sunlight does not reach it.

Although no trace of the ancient primeval forest remains, the gaze may recall a mysterious era, and the sight of a deer hopping through a raspberry bush brings to mind the fate of the forest mammals that must have changed over time.

In August, after the thunder and lightning, mushrooms begin to emerge and the competition among trees to grow against the clock becomes fierce.

We look back at how tiles, bricks, and chalk quarried from the chalk beds, which reveal the unique identity of the forest soil, were used in earlier times.

Under the golden September sun, wildflowers nearing the end of their lives spread their tiny seeds.

The adjacent mansions and cities grew up taking advantage of the forests and rivers, and trees were an essential part of the local economy.

Around this time of year, you can find precious truffles underground and observe the flying magpies that flutter like confetti in the air.

In October, the chestnut trees are full of fruit.

It's the time of year when you can explore the colorful mushrooms exploding throughout the forest, and spiders, seemingly under the guidance of a geometer, are busy building their nests for their final hunt.

In November, when frost falls and leaves fall, we reflect on the changing times of humanity centered around the forest and look into the world hidden beneath the rotten logs.

And we also investigate the mysterious forms of life that emerge and change within the deer droppings we collect in the forest.

In December, when ice grows on every branch, walking sticks are made from holly.

Even in the 18th and 19th centuries, people still exploited the forests, and due to poor road conditions, the forests became hideouts for highway robbers.

Lichens that clothe bare trees are like eternal sentinels warning of impending unseen change.

In January, I plan to make a collection box out of the cherry trees I felled.

And I also imagine the hardships of the sawmills, chair makers, and lathe workers who once worked in the forest.

Later, as we entered the industrial age, railroads were built and rowing competitions were held on rivers near cities, forests also took on new roles.

In February, when the trees in the forest are in hibernation, I go out in search of moss plants with a moss guide.

We read about the past from beer bottles found in the forest, and we also make charcoal, which has provided strong firepower for a long time.

In March, when the forest orchestra plays, we discover a dormouse nest and add to the story of the most diverse beetle on Earth.

I believe that forests must continue to be managed in the future, and that the countless creatures that live within them are all precious in their own right.

Beyond pure science and respect for life

A book that shows how nature and humans can coexist

“The forest poem I wrote is romantic yet scientific!”

This book is not just a simple forest story.

As a scientist, he does not stay in the realm of observation or thinking in order to be faithful to his role.

The author, Richard Forty, wanders freely and unconventionally, and does not hesitate to seek expert help when it comes to things in the forest that are beyond his own understanding.

Of course, the record is extremely detailed and not glossed over.

Readers of this book may be surprised to discover that so many living creatures live in forests, parks, or even beneath rotting tree stumps that they pass by without a second thought.

Even fungi, which require a microscope to observe at the molecular level, are not so far removed from us, and it is fascinating to look into what goes on in their world.

The setting of this book is Grimdike, a small forest near London, England.

Here, the author observes and experiences various things.

Sometimes through the eyes of a scientist, sometimes with the curiosity of a fourteen-year-old boy.

When researching and identifying related materials and documents, do not guess but always get confirmation from an expert.

And he records and organizes it in detail in his own way.

In addition, when he describes his daily life, thoughts, or the characteristic scenery of the forest that changes with the seasons, he transforms into a literary writer.

They make alcohol using ingredients from the forest, add unique flavors, and even make jam.

However, even within the same species, there are cases where they are called by different names, and cases where they are different species but are called by the same name.

To minimize such confusion, the plants, animals, and fungi mentioned in this book are given their common names, and the names used on government websites are used with preference.

In cases where there is no Korean name, the English name is used, and for plants, animals, and fungi with unclear names, the Latin scientific name is given and written in italics.

For reference, you can go to the website 'http://www.british-birdsongs.uk' and search for the scientific name of the bird mentioned in this book to hear the song of that bird.

The author also presents a gloomy outlook that if climate change accelerates on Earth, forests will also disappear.

In fact, humans are only a very small part of the natural world, and it is unclear how long they will reign as rulers of this Earth.

All organisms are as interesting as humans, and no less important than the observer.

When I think like that, I feel a sense of fear and my attitude towards nature inevitably changes.

Readers will be able to glimpse the future of nature and humanity in Richard Forty's delightful and joyful tale of forest life, which began to satisfy his own curiosity.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: April 20, 2018

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 416 pages | 730g | 152*225*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791188941025

- ISBN10: 118894102X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)