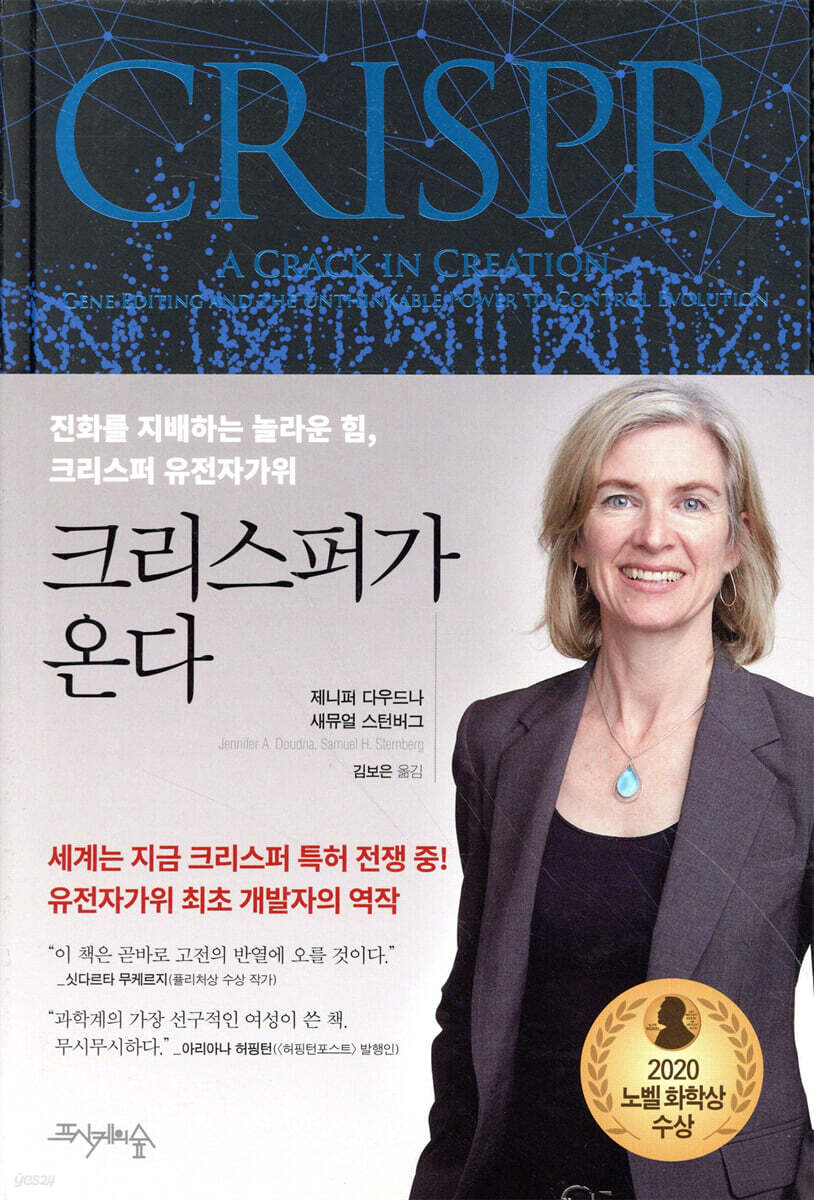

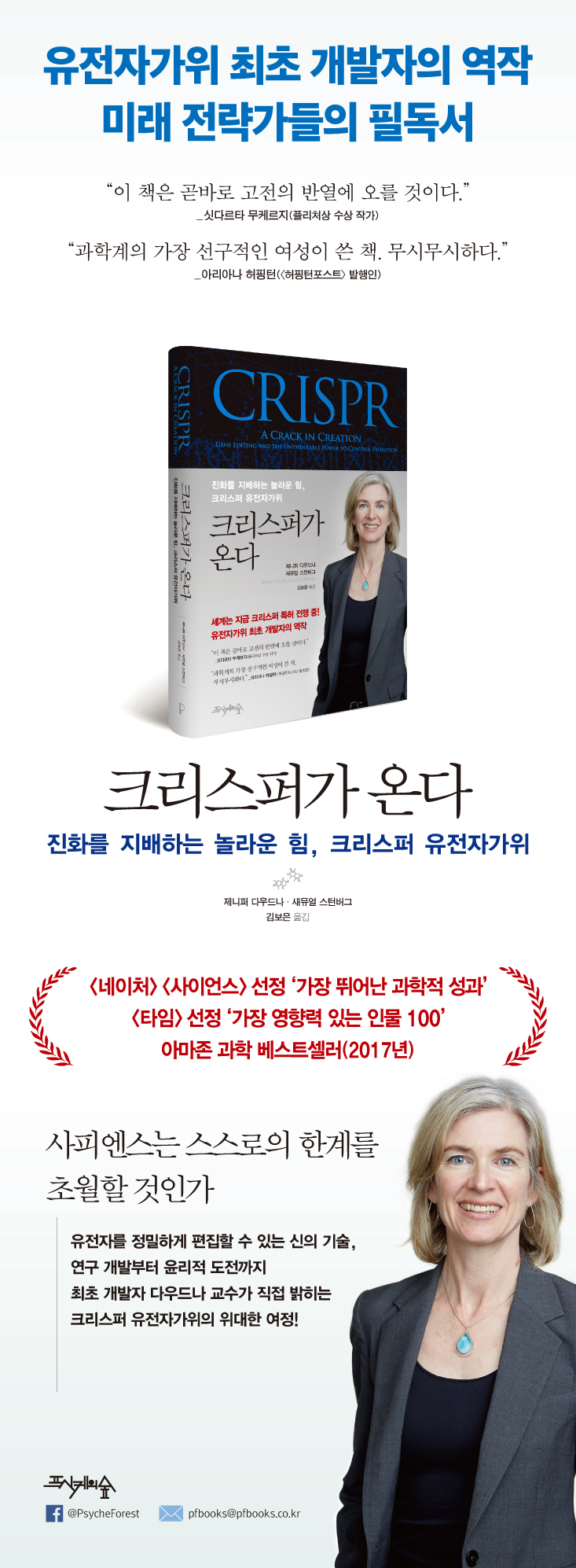

CRISPR is coming

|

Description

Book Introduction

“This book will soon become a classic.” —Siddhartha Mukherjee (Pulitzer Prize-winning author)

“A book written by one of the most pioneering women in science.

“It’s terrifying.” —Ariana Huffington, publisher of The Huffington Post

Selected as one of the "Best Scientific Achievements" by Nature and Science

Time's "100 Most Influential People"

Amazon Science Bestseller (2017)

Professor Doudna, the first developer of CRISPR, speaks

The great journey of gene scissors!

Humanity in the 21st century is trying to overcome its own limitations.

It sometimes brings excitement, sometimes fear.

This book deals with the 'CRISPR gene scissors', a core technology of such future discourse.

This is a must-read for anyone considering future strategies.

Gene editing is a cutting-edge technology that can precisely target and edit only the target genes, and is expected to provide a groundbreaking solution to the enormous problems facing humanity.

In particular, author Jennifer Doudna, who first developed the technology, clearly and in detail explains the research and development process of gene scissors and its principles in this book.

This book provides the most accurate general scientific knowledge about CRISPR.

What is noteworthy is that the author discusses in depth the 'practical applications' of CRISPR.

The gene scissors she developed are highly versatile and inexpensive, and have limitless industrial potential, not to mention the rapid advancements in the medical and agricultural industries.

In addition, there is a risk of indiscriminate use, so the ethical challenge is not trivial.

The author comprehensively examines these dualities and strongly urges a social and ethical discussion on gene editing.

Moreover, this book can be called a 'big history of biotechnology.'

From the discovery of the double helix to the elucidation of DNA/RNA, the Human Genome Project, and the invention of the first to third generation of genetic scissors, we will examine important milestones in the '50 years of biotechnology.'

In the process, the author's own research journey, which has achieved remarkable results as a female scientist, unfolds in an exciting way.

“A book written by one of the most pioneering women in science.

“It’s terrifying.” —Ariana Huffington, publisher of The Huffington Post

Selected as one of the "Best Scientific Achievements" by Nature and Science

Time's "100 Most Influential People"

Amazon Science Bestseller (2017)

Professor Doudna, the first developer of CRISPR, speaks

The great journey of gene scissors!

Humanity in the 21st century is trying to overcome its own limitations.

It sometimes brings excitement, sometimes fear.

This book deals with the 'CRISPR gene scissors', a core technology of such future discourse.

This is a must-read for anyone considering future strategies.

Gene editing is a cutting-edge technology that can precisely target and edit only the target genes, and is expected to provide a groundbreaking solution to the enormous problems facing humanity.

In particular, author Jennifer Doudna, who first developed the technology, clearly and in detail explains the research and development process of gene scissors and its principles in this book.

This book provides the most accurate general scientific knowledge about CRISPR.

What is noteworthy is that the author discusses in depth the 'practical applications' of CRISPR.

The gene scissors she developed are highly versatile and inexpensive, and have limitless industrial potential, not to mention the rapid advancements in the medical and agricultural industries.

In addition, there is a risk of indiscriminate use, so the ethical challenge is not trivial.

The author comprehensively examines these dualities and strongly urges a social and ethical discussion on gene editing.

Moreover, this book can be called a 'big history of biotechnology.'

From the discovery of the double helix to the elucidation of DNA/RNA, the Human Genome Project, and the invention of the first to third generation of genetic scissors, we will examine important milestones in the '50 years of biotechnology.'

In the process, the author's own research journey, which has achieved remarkable results as a female scientist, unfolds in an exciting way.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation│The CRISPR Revolution Begins_Professor Jin-soo Kim of Seoul National University

Prologue│Waves

Part 1 Tools

Chapter 1│The Search for Treatment

Chapter 2│New Defense Methods

Chapter 3: Decoding the Code

Chapter 4│Command and Control

Part 2 Tasks

Chapter 5│Crisper Zoo

Chapter 6│To treat patients

Chapter 7│Guessing

Chapter 8│What Lies Before Us

Epilogue│Start

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

Search

Prologue│Waves

Part 1 Tools

Chapter 1│The Search for Treatment

Chapter 2│New Defense Methods

Chapter 3: Decoding the Code

Chapter 4│Command and Control

Part 2 Tasks

Chapter 5│Crisper Zoo

Chapter 6│To treat patients

Chapter 7│Guessing

Chapter 8│What Lies Before Us

Epilogue│Start

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

main

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

Page 77 I will never forget the first time I heard the word 'Crisper'.

(…) Jillian briefly sketched the CRISPR structure.

First, I drew the bacterial cell as a large oval.

Then, the bacterial chromosome was drawn as a circle within an oval, and the DNA region was indicated by drawing a band of alternating diamonds and squares on one side of the circle.

This area was CRISPR.

Page 88: Is CRISPR another antiviral defense mechanism? The more I read about the arms race between bacteria and bacteriophages, the more I realize that another weapon system is just waiting to be discovered.

I couldn't hide my excitement any more.

Given how little we knew about CRISPR-related genes or Cas genes, the possibilities seemed astonishing.

Page 99 The speed and accuracy of research in this field was breathtaking.

In just a few years since I discovered CRISPR, the field has evolved from a loose collection of interesting but inconclusive papers to a comprehensive and unified theory of the inner workings of microbial adaptive immune systems.

CRISPR, which is only now beginning to be explored, is far more complex than we expected or imagined for simple single-celled organisms.

(…) But no one yet knew what effect this bacterial defense system would have on humans.

Page 131 We did it.

In a short period of time, we have established and demonstrated a new technology that can edit any genome, not just bacterial or viral genomes.

The results are based on studies targeting zinc finger nucleases and TALEN proteins.

With the fifth weapon system of bacteria, we have created a tool that can correct the code of life.

What a remarkable creature, a bacterium that has developed a way to program its warrior proteins to seek out and destroy viral DNA! What a miracle of good fortune, adapting an asset created for a different purpose for a completely different purpose.

Page 132: “We propose an alternative, RNA-programmed Cas9, that has great potential for gene targeting and gene editing.” On a clear Friday afternoon, June 8, 2012, I hit the “Confirm” button and formally submitted my paper to Science.

In 20 days, on June 28th, this paper will be published, and then there will be no turning back for me, my scientific colleagues, and the biological community.

Page 136 Numerous scientists around the world quickly explored the biochemical properties of CRISPR-Cas9 that we announced.

They were already using this new knowledge to manipulate the DNA of countless creatures, not just humans.

Academics and doctors have described CRISPR as the holy grail of genetic modification, a fast, simple, and accurate way to correct errors in the genetic code.

In the blink of an eye, I went from the world of bacterial and CRISPR-Cas biology to the world of human biology and medicine.

Pages 166-167 The real reason CRISPR has exploded with such power and vitality on the biotechnology stage is its low cost and ease of use.

Any scientist can now use CRISPR to edit genes.

Previous technologies like zinc finger nucleases and TALENs were difficult to design and prohibitively expensive.

However, using CRISPR, scientists can easily design a gene to target the gene they are studying, prepare the necessary Cas9 and guide RNA, and conduct the experiment directly using standard experimental techniques.

All of this doesn't take long and doesn't require any outside help.

All you need to start your experiment is an artificial chromosome, or plasmid, containing the basic CRISPR.

Within a few years of its discovery, CRISPR was used to edit rice genes to confer bacterial blight resistance, and soon after, it was used to confer herbicide resistance in corn, soybeans, and potatoes.

It was also used to produce mushrooms that were resistant to browning and did not spoil before shipment.

Scientists have used CRISPR to edit the genome of oranges, and now they are trying to use it to save U.S. citrus crops from the bacterial plant disease huanglongbing.

A research team led by Korean scientist Jin-soo Kim is attempting to edit banana genes to prevent the extinction of Cavendish bananas, which are threatened by the spread of soil fungi.

CRISPR, a 200-page tool, allows scientists to create transgenic animals with more precise genetic control, further improving the production of biopharmaceutical drugs.

For example, experiments on pigs have demonstrated that CRISPR can efficiently produce the therapeutic proteins encoded by pig genes by replacing them with their human counterparts.

New technologies, including CRISPR, offer a way to use pigs to produce organs suitable for transplant into humans.

Gene editing has now enabled the suppression of pig genes that trigger human immune responses and the elimination of pig viruses that can lurk in the pig genome and infect humans during organ transplants.

(…) The goal is to provide an ‘unlimited supply of transplant organs’ produced on demand.

Page 205 Thanks to easy gene editing technology, consumers will be able to order any breed of dog to enhance their desired tastes.

What else could be done? If we've successfully genetically engineered hornless cows, why not use this technology to grow horns in horses?

Page 207 CRISPR offers another way to restore extinct animals.

It's not much different from the dinosaur restoration plan depicted in the novel and the 1993 Hollywood film Jurassic Park.

Whether it's preventing mosquitoes from transmitting specific pathogens or eradicating them altogether, CRISPR-based gene drives could be the best weapon we have against the widespread threat of mosquitoes.

Above all, genetic strategies like CRISPR may be safer than toxic pesticides and have the appeal of solving biological problems with biology.

Page 222 In about two years, scientists will be using CRISPR to treat not only muscular dystrophy in living mice, but also a variety of liver metabolic disorders.

On one hand, human cells derived from patient tissue samples will be cultured, and hundreds of scientists will use CRISPR to correct DNA mutations associated with an ever-growing number of devastating genetic diseases.

All diseases are covered, from sickle cell disease to hemophilia, cystic fibrosis, and severe combined immunodeficiency.

Gene editing on page 230 could solve this problem because the patient would be both the donor and recipient of stem cells.

If a doctor isolates stem cells from a patient's bone marrow, corrects the beta-globin gene mutation with CRISPR, and then injects the edited cells into the patient, there is no need to worry about a shortage of donors or immune rejection between the patient and the transplanted cells.

Unlike previous gene-editing technologies, the design process for landing CRISPR on a new 20-base sequence of a target gene in the genome is so simple that even a high school student could do it.

In fact, it's so simple that a computer program could do it.

Scientists are now combining computer science and gene editing to probe the deepest recesses of the genome and discover new cancer-linked genes without prior knowledge.

Page 253 CRISPR technology is relatively new, but it would be difficult to find a disease that CRISPR hasn't been mentioned as a treatment for.

In principle, any disease that involves a specific mutation or defect in a DNA sequence can be treated using CRISPR to correct the mutation or replace the damaged gene with a healthy sequence.

Page 254 I believe we should ban the use of CRISPR technology to permanently alter the genomes of our descendants, at least until we have fully considered the potential problems that gene editing in human germ cells would pose.

Until the safety and ethical issues involved are better understood and more stakeholders are involved in the discussion, scientists should not tamper with germ cells.

Page 259 I became increasingly concerned as I imagined CRISPR being used for other purposes.

Have our discoveries made gene editing "too" easy? Are scientists rushing headlong into new fields of research without considering the potential consequences or validity of their work? Could CRISPR be exploited or abused, particularly in areas involving the human genome?

Page 274: What have we done? Emmanuel and I, along with our scientific colleagues, hoped that CRISPR technology could cure genetic diseases and save patients.

Not now, but back then we had no idea that our research results would be distorted in all sorts of ways imaginable.

I felt like Dr. Frankenstein, overwhelmed by how quickly everything had happened and how quickly things could go wrong.

Did I create a monster?

Page 276 I wanted to move ahead and find a way to create an honest and open public discourse about this technology that I had helped to create.

Can I and other scientists save CRISPR from itself before a catastrophe strikes, rather than after it becomes a reality like an atomic bomb? I found the answer in another pivotal moment in biotechnology history, a case where warning voices resonated throughout the scientific community and beyond.

In the blink of an eye, CRISPR went from being a revolutionary but relatively obscure technology to a household word.

Now that the extraordinary impact CRISPR technology will have on future humanity has been revealed, I hope we will all have a broad and honest conversation about germline editing: when we will allow its use, how we will regulate it, and what impacts we will or will not have to accept.

While it's great to finally see the beginning of a public discussion about CRISPR, there's still a long way to go.

On page 299, it became clear that technological advancement would not wait for scientists and the public to reach an agreement that was difficult to achieve.

Imagine that classes are distinguished 'both' along socioeconomic and genetic lines.

Imagine a future where the wealthy enjoy healthier, longer lives thanks to the genes of the privileged. It sounds like something straight out of a science fiction novel, but if germline editing becomes widespread, this fantasy could become reality.

The power to control your own genetic future is both wondrous and terrifying.

Deciding how to handle this technology may be the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced.

I hope and believe we can handle it.

(…) Jillian briefly sketched the CRISPR structure.

First, I drew the bacterial cell as a large oval.

Then, the bacterial chromosome was drawn as a circle within an oval, and the DNA region was indicated by drawing a band of alternating diamonds and squares on one side of the circle.

This area was CRISPR.

Page 88: Is CRISPR another antiviral defense mechanism? The more I read about the arms race between bacteria and bacteriophages, the more I realize that another weapon system is just waiting to be discovered.

I couldn't hide my excitement any more.

Given how little we knew about CRISPR-related genes or Cas genes, the possibilities seemed astonishing.

Page 99 The speed and accuracy of research in this field was breathtaking.

In just a few years since I discovered CRISPR, the field has evolved from a loose collection of interesting but inconclusive papers to a comprehensive and unified theory of the inner workings of microbial adaptive immune systems.

CRISPR, which is only now beginning to be explored, is far more complex than we expected or imagined for simple single-celled organisms.

(…) But no one yet knew what effect this bacterial defense system would have on humans.

Page 131 We did it.

In a short period of time, we have established and demonstrated a new technology that can edit any genome, not just bacterial or viral genomes.

The results are based on studies targeting zinc finger nucleases and TALEN proteins.

With the fifth weapon system of bacteria, we have created a tool that can correct the code of life.

What a remarkable creature, a bacterium that has developed a way to program its warrior proteins to seek out and destroy viral DNA! What a miracle of good fortune, adapting an asset created for a different purpose for a completely different purpose.

Page 132: “We propose an alternative, RNA-programmed Cas9, that has great potential for gene targeting and gene editing.” On a clear Friday afternoon, June 8, 2012, I hit the “Confirm” button and formally submitted my paper to Science.

In 20 days, on June 28th, this paper will be published, and then there will be no turning back for me, my scientific colleagues, and the biological community.

Page 136 Numerous scientists around the world quickly explored the biochemical properties of CRISPR-Cas9 that we announced.

They were already using this new knowledge to manipulate the DNA of countless creatures, not just humans.

Academics and doctors have described CRISPR as the holy grail of genetic modification, a fast, simple, and accurate way to correct errors in the genetic code.

In the blink of an eye, I went from the world of bacterial and CRISPR-Cas biology to the world of human biology and medicine.

Pages 166-167 The real reason CRISPR has exploded with such power and vitality on the biotechnology stage is its low cost and ease of use.

Any scientist can now use CRISPR to edit genes.

Previous technologies like zinc finger nucleases and TALENs were difficult to design and prohibitively expensive.

However, using CRISPR, scientists can easily design a gene to target the gene they are studying, prepare the necessary Cas9 and guide RNA, and conduct the experiment directly using standard experimental techniques.

All of this doesn't take long and doesn't require any outside help.

All you need to start your experiment is an artificial chromosome, or plasmid, containing the basic CRISPR.

Within a few years of its discovery, CRISPR was used to edit rice genes to confer bacterial blight resistance, and soon after, it was used to confer herbicide resistance in corn, soybeans, and potatoes.

It was also used to produce mushrooms that were resistant to browning and did not spoil before shipment.

Scientists have used CRISPR to edit the genome of oranges, and now they are trying to use it to save U.S. citrus crops from the bacterial plant disease huanglongbing.

A research team led by Korean scientist Jin-soo Kim is attempting to edit banana genes to prevent the extinction of Cavendish bananas, which are threatened by the spread of soil fungi.

CRISPR, a 200-page tool, allows scientists to create transgenic animals with more precise genetic control, further improving the production of biopharmaceutical drugs.

For example, experiments on pigs have demonstrated that CRISPR can efficiently produce the therapeutic proteins encoded by pig genes by replacing them with their human counterparts.

New technologies, including CRISPR, offer a way to use pigs to produce organs suitable for transplant into humans.

Gene editing has now enabled the suppression of pig genes that trigger human immune responses and the elimination of pig viruses that can lurk in the pig genome and infect humans during organ transplants.

(…) The goal is to provide an ‘unlimited supply of transplant organs’ produced on demand.

Page 205 Thanks to easy gene editing technology, consumers will be able to order any breed of dog to enhance their desired tastes.

What else could be done? If we've successfully genetically engineered hornless cows, why not use this technology to grow horns in horses?

Page 207 CRISPR offers another way to restore extinct animals.

It's not much different from the dinosaur restoration plan depicted in the novel and the 1993 Hollywood film Jurassic Park.

Whether it's preventing mosquitoes from transmitting specific pathogens or eradicating them altogether, CRISPR-based gene drives could be the best weapon we have against the widespread threat of mosquitoes.

Above all, genetic strategies like CRISPR may be safer than toxic pesticides and have the appeal of solving biological problems with biology.

Page 222 In about two years, scientists will be using CRISPR to treat not only muscular dystrophy in living mice, but also a variety of liver metabolic disorders.

On one hand, human cells derived from patient tissue samples will be cultured, and hundreds of scientists will use CRISPR to correct DNA mutations associated with an ever-growing number of devastating genetic diseases.

All diseases are covered, from sickle cell disease to hemophilia, cystic fibrosis, and severe combined immunodeficiency.

Gene editing on page 230 could solve this problem because the patient would be both the donor and recipient of stem cells.

If a doctor isolates stem cells from a patient's bone marrow, corrects the beta-globin gene mutation with CRISPR, and then injects the edited cells into the patient, there is no need to worry about a shortage of donors or immune rejection between the patient and the transplanted cells.

Unlike previous gene-editing technologies, the design process for landing CRISPR on a new 20-base sequence of a target gene in the genome is so simple that even a high school student could do it.

In fact, it's so simple that a computer program could do it.

Scientists are now combining computer science and gene editing to probe the deepest recesses of the genome and discover new cancer-linked genes without prior knowledge.

Page 253 CRISPR technology is relatively new, but it would be difficult to find a disease that CRISPR hasn't been mentioned as a treatment for.

In principle, any disease that involves a specific mutation or defect in a DNA sequence can be treated using CRISPR to correct the mutation or replace the damaged gene with a healthy sequence.

Page 254 I believe we should ban the use of CRISPR technology to permanently alter the genomes of our descendants, at least until we have fully considered the potential problems that gene editing in human germ cells would pose.

Until the safety and ethical issues involved are better understood and more stakeholders are involved in the discussion, scientists should not tamper with germ cells.

Page 259 I became increasingly concerned as I imagined CRISPR being used for other purposes.

Have our discoveries made gene editing "too" easy? Are scientists rushing headlong into new fields of research without considering the potential consequences or validity of their work? Could CRISPR be exploited or abused, particularly in areas involving the human genome?

Page 274: What have we done? Emmanuel and I, along with our scientific colleagues, hoped that CRISPR technology could cure genetic diseases and save patients.

Not now, but back then we had no idea that our research results would be distorted in all sorts of ways imaginable.

I felt like Dr. Frankenstein, overwhelmed by how quickly everything had happened and how quickly things could go wrong.

Did I create a monster?

Page 276 I wanted to move ahead and find a way to create an honest and open public discourse about this technology that I had helped to create.

Can I and other scientists save CRISPR from itself before a catastrophe strikes, rather than after it becomes a reality like an atomic bomb? I found the answer in another pivotal moment in biotechnology history, a case where warning voices resonated throughout the scientific community and beyond.

In the blink of an eye, CRISPR went from being a revolutionary but relatively obscure technology to a household word.

Now that the extraordinary impact CRISPR technology will have on future humanity has been revealed, I hope we will all have a broad and honest conversation about germline editing: when we will allow its use, how we will regulate it, and what impacts we will or will not have to accept.

While it's great to finally see the beginning of a public discussion about CRISPR, there's still a long way to go.

On page 299, it became clear that technological advancement would not wait for scientists and the public to reach an agreement that was difficult to achieve.

Imagine that classes are distinguished 'both' along socioeconomic and genetic lines.

Imagine a future where the wealthy enjoy healthier, longer lives thanks to the genes of the privileged. It sounds like something straight out of a science fiction novel, but if germline editing becomes widespread, this fantasy could become reality.

The power to control your own genetic future is both wondrous and terrifying.

Deciding how to handle this technology may be the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced.

I hope and believe we can handle it.

--- From the text

Publisher's Review

A must-read for future strategists

A biology textbook from the forefront of science

In June 2012, a research paper published in the journal Science shook the scientific community.

The paper, jointly published by Professor Jennifer Doudna and Professor Emminuel Charpentier, covered the third-generation gene-editing technology, CRISPR-Cas9.

CRISPR gene scissors, which have 'revolutionarily' surpassed the achievements of the first and second generation technologies, are now inexpensive, costing only a few tens of thousands of won (previously costing tens of millions of won), and the probability of errors has been drastically reduced, and the time required for gene editing has also been significantly reduced.

Anyone can now perform sophisticated, inexpensive gene editing.

The author of this book, Professor Jennifer Doudna, is credited with changing the paradigm of 21st-century biotechnology and has swept major prestigious awards.

In 2015, the two major scientific journals, Nature and Science, selected CRISPR gene scissors as the “most outstanding scientific achievement,” and that year, Time magazine selected Professor Doudna as one of the “100 Most Influential People.”

She is currently being considered as a strong candidate for the Nobel Prize.

So what exactly is CRISPR, and what makes it so revolutionary?

Part 1 of this book, "Tools," details the journey of gene editing research.

Since Watson and Crick discovered the DNA double helix, the field of biotechnology has undergone several revolutions. A comprehensive range of fundamental research has been conducted, from the elucidation of RNA to the unique mechanism of homologous recombination to the Human Genome Project.

Based on this, editing of specific parts of the 3 billion base pairs was attempted.

If we could control our genes in such fine detail, humans would face a whole new dimension of reality.

However, the first-generation technology, Zinc Finger Nuclease, and the second-generation technology, Talen, fell short of expectations.

They were too dull scissors and too expensive to be commercialized.

The author explores both the groundbreaking aspects and limitations of these technologies, while providing a captivating account of the characteristics and research process of his own third-generation technology.

Readers will gain comprehensive knowledge of CRISPR gene editing from this biology textbook, brought to you from the forefront of science.

The divine technology that rushes towards the singularity,

Will Sapiens Transcend Their Own Limits?

If Part 1 covers the journey of research and development, Part 2, 'Tasks,' covers stories related to the practical application of technology.

There are science fiction stories that are made possible by CRISPR technology.

Muscle-enhanced dogs, hornless cows, and fluorescent pigs are already a reality.

“You can make a furry mammoth, a winged lizard, or a unicorn.

“This is no joke.” (p. 173)

More important than these fascinating stories is the medical potential of CRISPR.

CRISPR technology is expected to be a new turning point in the treatment of congenital genetic diseases, incurable diseases, AIDS, and cancer.

If we can identify the genetic part of the disease, we can treat it by editing that part with CRISPR gene scissors.

What if we could genetically edit pig organs to make them as close to human as possible for xenotransplantation?

If that happens, we can overcome the reality that “an average of 22 people die every day while waiting for an organ transplant” (of course, there remains the important issue of overcoming emotional and ethical resistance).

Research is already underway applying CRISPR technology to various diseases.

“Scientists are using CRISPR to create more accurate and flexible models of human diseases in laboratory animals than ever before.

“We create a model of autism using monkeys, a model of Parkinson’s disease using pigs, and a model of influenza using ferrets.” (p. 174)

CRISPR technology also holds significant potential for solving food problems.

The United Nations projects that the world's population will approach 10 billion by 2050.

It may not seem like it in Korea today, but if that happens, the whole world will face food shortages and mass starvation.

Biotechnology, represented by gene scissors, offers a powerful alternative to avoiding Malthus' curse.

“In the coming years, these new biotechnology technologies will bring us higher-yielding crops, healthier livestock, and more nutritious foods.” (p. 173)

“Gene editing technology challenges human morality,

“It will create amazing opportunities at the same time.”_Walter Isaacson (author of Steve Jobs)

According to the author, you can now set up a CRISPR lab for around $2,000, and purchase a gene editing kit for $150.

Anyone with imagination can attempt the so-called 'intelligent design' of living things.

The price itself is an innovation of the third generation gene scissors.

This has a double-sided nature.

What if some mad scientist created a chimera?

This problem becomes particularly acute when the technology is applied to human embryos.

Immortal humans, superhumans, are both fascinating and dangerous.

Author Jennifer Doudna says she's come to grips with the dangers of indiscriminate CRISPR use.

She feels uneasy about the Pandora's box she has opened, and draws significant reference to the precedent of the invention of the atomic bomb.

“The words of Oppenheimer, the ‘father of the atomic bomb,’ only added to my guilt.

Perhaps in the distant future we might be saying the same thing about CRISPR and genetically modified humans.

“While human genome editing may not result in a catastrophe on par with nuclear weapons, the reckless rush to CRISPR research still doesn’t look good.” (p. 275)

With this in mind, Jennifer Doudna led the International Conference on Human Genome Editing in 2015.

Not only scientists, but also philosophers, politicians, lawyers, and historians participated in the wide-ranging discussion.

Professor Kim Jin-su of Seoul National University, who wrote the preface to the Korean edition of this book, is said to have also been invited to this meeting.

This demonstrates that establishing guidelines for CRISPR technology is an interdisciplinary and international issue.

This book strongly encourages ethical discussion by addressing key issues related to it.

The world is now in a CRISPR patent war!

What's next for Korea after semiconductors?

CRISPR technology is not just science.

Without social consensus, research will inevitably be limited.

The question of how far research should be allowed is very important.

In Korea, research was severely discouraged in the 2000s following the Hwang Woo-suk incident.

The collapse of public trust in the technology has led to a collapse of trust in biotechnology in general, which has led to strong regulation.

Meanwhile, the United States and China expanded their research.

CRISPR technology is now very close to commercialization, and with the expected massive industrial scale, a fierce patent war is raging between research institutes.

Jennifer Doudna doesn't address patent-related issues in this book, but she too is a key player in the "patent war of the century."

The reason the author pays particular attention to ethical issues in this book is because it has significant implications for the Korean situation.

She wants to build public trust in CRISPR technology.

“Given the widespread anxiety and resistance to certain forms of genetic modification in agriculture, I am particularly concerned that a lack of public information about germline editing could hinder efforts to use CRISPR more safely and importantly.” (p. 275)

South Korea is currently considered one of the top three countries in the world for CRISPR technology.

Professor Jin-soo Kim of Seoul National University has secured world-class technology while leading the Genome Editing Research Group at the Institute for Basic Science.

In the recommended preface to this book, he also argues for the need for public discussion.

“I hope that with the publication of this book in Korea, experts and the general public will study and discuss together about the future that gene scissors technology will create in our society, so that we can abolish anachronistic and inappropriate regulations and establish reasonable measures.” (p. 10) A principled opposition to biotechnology is ethically sound.

But it is time to think about the unethicality and foolishness of shutting down the discussion so simply.

Includes a special recommendation foreword to the Korean edition

Professor Kim Jin-su of Seoul National University and founder of ToolGen

“Just a few years ago, CRISPR or gene scissors was an academic term used only among a very small number of life scientists, and was unfamiliar to the general public, as well as most biologists.

But now it is receiving so much public attention that everyone has probably heard of it at least once.

"Crispr is Coming" is a book that introduces the experience of Professor Jennifer Doudna of the University of California, Berkeley, who first discovered how this tool works.

Furthermore, the author urges both scientists and the general public to consider the benefits, changes, and ethical implications that this tool will bring to humanity.”

The Research Growth of an Outstanding Female Scientist

The translator saw it this way

“While translating Part 1, which is detailed yet appropriately branched out on biological mechanisms, I was impressed by the smooth writing style, but the passage that left the deepest impression on me was the one in which Professor Doudna described the moment he first entered the lab as an undergraduate.

This passage, which describes a quiet, yet passionate laboratory at the University of Hawaii, is only the introduction to Chapter 3, but it brought back a vague sense of nostalgia as I recalled the moment I first entered the laboratory.

Perhaps Professor Dowdna also wrote that sentence in a moment of nostalgia.

There are also a few brief sections in the text that briefly describe biochemical experimental techniques. When I was translating those sections, I found myself smiling as I recalled my time working in the lab.

Actually, I don't only have memories that make me laugh.

It was a sad sight to see Mitch return to Germany with his shoulders slumped as the experiment results did not go as planned, as it was a common sight in the laboratory.

“It’s a strange feeling to think that sentences and explanations like these, which trigger memories for those who stayed in the laboratory, will also be a switch that overlaps the bizarre world with reality for others who look into this world through books.”

A biology textbook from the forefront of science

In June 2012, a research paper published in the journal Science shook the scientific community.

The paper, jointly published by Professor Jennifer Doudna and Professor Emminuel Charpentier, covered the third-generation gene-editing technology, CRISPR-Cas9.

CRISPR gene scissors, which have 'revolutionarily' surpassed the achievements of the first and second generation technologies, are now inexpensive, costing only a few tens of thousands of won (previously costing tens of millions of won), and the probability of errors has been drastically reduced, and the time required for gene editing has also been significantly reduced.

Anyone can now perform sophisticated, inexpensive gene editing.

The author of this book, Professor Jennifer Doudna, is credited with changing the paradigm of 21st-century biotechnology and has swept major prestigious awards.

In 2015, the two major scientific journals, Nature and Science, selected CRISPR gene scissors as the “most outstanding scientific achievement,” and that year, Time magazine selected Professor Doudna as one of the “100 Most Influential People.”

She is currently being considered as a strong candidate for the Nobel Prize.

So what exactly is CRISPR, and what makes it so revolutionary?

Part 1 of this book, "Tools," details the journey of gene editing research.

Since Watson and Crick discovered the DNA double helix, the field of biotechnology has undergone several revolutions. A comprehensive range of fundamental research has been conducted, from the elucidation of RNA to the unique mechanism of homologous recombination to the Human Genome Project.

Based on this, editing of specific parts of the 3 billion base pairs was attempted.

If we could control our genes in such fine detail, humans would face a whole new dimension of reality.

However, the first-generation technology, Zinc Finger Nuclease, and the second-generation technology, Talen, fell short of expectations.

They were too dull scissors and too expensive to be commercialized.

The author explores both the groundbreaking aspects and limitations of these technologies, while providing a captivating account of the characteristics and research process of his own third-generation technology.

Readers will gain comprehensive knowledge of CRISPR gene editing from this biology textbook, brought to you from the forefront of science.

The divine technology that rushes towards the singularity,

Will Sapiens Transcend Their Own Limits?

If Part 1 covers the journey of research and development, Part 2, 'Tasks,' covers stories related to the practical application of technology.

There are science fiction stories that are made possible by CRISPR technology.

Muscle-enhanced dogs, hornless cows, and fluorescent pigs are already a reality.

“You can make a furry mammoth, a winged lizard, or a unicorn.

“This is no joke.” (p. 173)

More important than these fascinating stories is the medical potential of CRISPR.

CRISPR technology is expected to be a new turning point in the treatment of congenital genetic diseases, incurable diseases, AIDS, and cancer.

If we can identify the genetic part of the disease, we can treat it by editing that part with CRISPR gene scissors.

What if we could genetically edit pig organs to make them as close to human as possible for xenotransplantation?

If that happens, we can overcome the reality that “an average of 22 people die every day while waiting for an organ transplant” (of course, there remains the important issue of overcoming emotional and ethical resistance).

Research is already underway applying CRISPR technology to various diseases.

“Scientists are using CRISPR to create more accurate and flexible models of human diseases in laboratory animals than ever before.

“We create a model of autism using monkeys, a model of Parkinson’s disease using pigs, and a model of influenza using ferrets.” (p. 174)

CRISPR technology also holds significant potential for solving food problems.

The United Nations projects that the world's population will approach 10 billion by 2050.

It may not seem like it in Korea today, but if that happens, the whole world will face food shortages and mass starvation.

Biotechnology, represented by gene scissors, offers a powerful alternative to avoiding Malthus' curse.

“In the coming years, these new biotechnology technologies will bring us higher-yielding crops, healthier livestock, and more nutritious foods.” (p. 173)

“Gene editing technology challenges human morality,

“It will create amazing opportunities at the same time.”_Walter Isaacson (author of Steve Jobs)

According to the author, you can now set up a CRISPR lab for around $2,000, and purchase a gene editing kit for $150.

Anyone with imagination can attempt the so-called 'intelligent design' of living things.

The price itself is an innovation of the third generation gene scissors.

This has a double-sided nature.

What if some mad scientist created a chimera?

This problem becomes particularly acute when the technology is applied to human embryos.

Immortal humans, superhumans, are both fascinating and dangerous.

Author Jennifer Doudna says she's come to grips with the dangers of indiscriminate CRISPR use.

She feels uneasy about the Pandora's box she has opened, and draws significant reference to the precedent of the invention of the atomic bomb.

“The words of Oppenheimer, the ‘father of the atomic bomb,’ only added to my guilt.

Perhaps in the distant future we might be saying the same thing about CRISPR and genetically modified humans.

“While human genome editing may not result in a catastrophe on par with nuclear weapons, the reckless rush to CRISPR research still doesn’t look good.” (p. 275)

With this in mind, Jennifer Doudna led the International Conference on Human Genome Editing in 2015.

Not only scientists, but also philosophers, politicians, lawyers, and historians participated in the wide-ranging discussion.

Professor Kim Jin-su of Seoul National University, who wrote the preface to the Korean edition of this book, is said to have also been invited to this meeting.

This demonstrates that establishing guidelines for CRISPR technology is an interdisciplinary and international issue.

This book strongly encourages ethical discussion by addressing key issues related to it.

The world is now in a CRISPR patent war!

What's next for Korea after semiconductors?

CRISPR technology is not just science.

Without social consensus, research will inevitably be limited.

The question of how far research should be allowed is very important.

In Korea, research was severely discouraged in the 2000s following the Hwang Woo-suk incident.

The collapse of public trust in the technology has led to a collapse of trust in biotechnology in general, which has led to strong regulation.

Meanwhile, the United States and China expanded their research.

CRISPR technology is now very close to commercialization, and with the expected massive industrial scale, a fierce patent war is raging between research institutes.

Jennifer Doudna doesn't address patent-related issues in this book, but she too is a key player in the "patent war of the century."

The reason the author pays particular attention to ethical issues in this book is because it has significant implications for the Korean situation.

She wants to build public trust in CRISPR technology.

“Given the widespread anxiety and resistance to certain forms of genetic modification in agriculture, I am particularly concerned that a lack of public information about germline editing could hinder efforts to use CRISPR more safely and importantly.” (p. 275)

South Korea is currently considered one of the top three countries in the world for CRISPR technology.

Professor Jin-soo Kim of Seoul National University has secured world-class technology while leading the Genome Editing Research Group at the Institute for Basic Science.

In the recommended preface to this book, he also argues for the need for public discussion.

“I hope that with the publication of this book in Korea, experts and the general public will study and discuss together about the future that gene scissors technology will create in our society, so that we can abolish anachronistic and inappropriate regulations and establish reasonable measures.” (p. 10) A principled opposition to biotechnology is ethically sound.

But it is time to think about the unethicality and foolishness of shutting down the discussion so simply.

Includes a special recommendation foreword to the Korean edition

Professor Kim Jin-su of Seoul National University and founder of ToolGen

“Just a few years ago, CRISPR or gene scissors was an academic term used only among a very small number of life scientists, and was unfamiliar to the general public, as well as most biologists.

But now it is receiving so much public attention that everyone has probably heard of it at least once.

"Crispr is Coming" is a book that introduces the experience of Professor Jennifer Doudna of the University of California, Berkeley, who first discovered how this tool works.

Furthermore, the author urges both scientists and the general public to consider the benefits, changes, and ethical implications that this tool will bring to humanity.”

The Research Growth of an Outstanding Female Scientist

The translator saw it this way

“While translating Part 1, which is detailed yet appropriately branched out on biological mechanisms, I was impressed by the smooth writing style, but the passage that left the deepest impression on me was the one in which Professor Doudna described the moment he first entered the lab as an undergraduate.

This passage, which describes a quiet, yet passionate laboratory at the University of Hawaii, is only the introduction to Chapter 3, but it brought back a vague sense of nostalgia as I recalled the moment I first entered the laboratory.

Perhaps Professor Dowdna also wrote that sentence in a moment of nostalgia.

There are also a few brief sections in the text that briefly describe biochemical experimental techniques. When I was translating those sections, I found myself smiling as I recalled my time working in the lab.

Actually, I don't only have memories that make me laugh.

It was a sad sight to see Mitch return to Germany with his shoulders slumped as the experiment results did not go as planned, as it was a common sight in the laboratory.

“It’s a strange feeling to think that sentences and explanations like these, which trigger memories for those who stayed in the laboratory, will also be a switch that overlaps the bizarre world with reality for others who look into this world through books.”

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: April 2, 2018

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 372 pages | 767g | 160*232*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791196155636

- ISBN10: 1196155631

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)