Song of the Tree

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

Poetic sensibility and deep insightA new book by David George Haskell, considered "one of the finest nature writers of our time."

In this book, which records his research on twelve species of trees from around the world, he emphasizes that humans and nature are not in conflict, but rather are interconnected within one vast history of life.

An intelligent and beautiful book.

February 13, 2018. Natural Science PD

The second book by David George Haskell, author of "The Forest View of the Universe."

The author, who is considered one of the "best nature literature writers of our time," observed and recorded twelve species of trees from around the world, including the Amazon rainforest, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict zone, Scotland, and East Asian Japan.

It transcends time and space, describing humanity, nature, society, history, and philosophical insights in beautiful sentences.

The author's insight that humans and nature form a vast interconnected network throughout the origins and history of life leads to the search for a new ethics that transcends the individualism, ethical nihilism, and dichotomy of human versus nature in our time.

It presents readers with poetic and elegant prose, as well as calm and meticulous scientific inquiry, and dazzling insights into humanity and nature.

The author, who is considered one of the "best nature literature writers of our time," observed and recorded twelve species of trees from around the world, including the Amazon rainforest, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict zone, Scotland, and East Asian Japan.

It transcends time and space, describing humanity, nature, society, history, and philosophical insights in beautiful sentences.

The author's insight that humans and nature form a vast interconnected network throughout the origins and history of life leads to the search for a new ethics that transcends the individualism, ethical nihilism, and dichotomy of human versus nature in our time.

It presents readers with poetic and elegant prose, as well as calm and meticulous scientific inquiry, and dazzling insights into humanity and nature.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface 008

| Part 1 |

Kapok Tree 013

Balsam fir 049

Sabal Palm Tree 084

Red maple 114

Intermission: Samjidak Tree 132

| Part 2 |

Hazelnut 141

Redwood and Ponderosa Pine 162

Interlude: Maple 201

| Part 3 |

Poplar tree 211

Soybean tree 244

Olive Tree 278

Island Pine 312

Acknowledgements 327

Reference 332

Search 363

| Part 1 |

Kapok Tree 013

Balsam fir 049

Sabal Palm Tree 084

Red maple 114

Intermission: Samjidak Tree 132

| Part 2 |

Hazelnut 141

Redwood and Ponderosa Pine 162

Interlude: Maple 201

| Part 3 |

Poplar tree 211

Soybean tree 244

Olive Tree 278

Island Pine 312

Acknowledgements 327

Reference 332

Search 363

Detailed image

Into the book

Since life is a web, there is no such thing as ‘nature’ or ‘environment’ that is separate from humans.

The human-nature dichotomy lies at the heart of many philosophies, but from a biological perspective, it is an illusion.

Because we are part of a community of life formed through relationships with ‘others.’

To borrow a folk song lyric, we are 'travelers traveling through this world.'

Nor are we alienated creatures, cut off from nature (as Wordsworth spoke of in his lyric poetry) and placed in an artificial “dead pool” that “distorts the beautiful forms of things.”

Our bodies and minds, our “science and art,” have not deviated from nature in the least.

We cannot leave the song of life.

This music made us, it is our essence.

Therefore, our ethics must be an ethics of belonging.

This ethical imperative is all the more urgent now that human actions are disrupting, reconnecting, and wearing down the world's biological web.

Therefore, to listen to trees, nature's great connectors, is to learn to dwell in relationship, in the relationship that gives life its source, its material, and its beauty. (pp. 9-10)

The belief that nature is other, a separate realm, and polluted by unnatural human traces is a denial of our own wildness.

Concrete sidewalks, the spurts of paint from a factory, and city hall documents planning Denver's growth are as natural as the rustling of maple leaves, the calls of baby woodpeckers, or the nesting of a swallow, in that they are manifestations of primates' evolved mental abilities to manipulate their environment.

Of course, whether all these natural phenomena are wise, beautiful, just and good is a separate question.

…nature does not produce dividends.

The economy of all species is contained entirely within nature.

Nature doesn't need a home.

Nature is home.

We are not deprived of nature.

Even when we are not aware of this nature, we are nature.

When we understand that we belong to this world, we develop the discernment to recognize the beautiful and the good within the human spirit, not from the outside, but from within the entangled web of life. (pp. 232-233)

The atmosphere and plants create each other.

At this time, plants are temporary crystals of carbon, and the air is a product of 400 million years of breathing forests.

Trees and air have no narrative, no telos of their own.

Because neither of them are themselves. (p. 322)

The human-nature dichotomy lies at the heart of many philosophies, but from a biological perspective, it is an illusion.

Because we are part of a community of life formed through relationships with ‘others.’

To borrow a folk song lyric, we are 'travelers traveling through this world.'

Nor are we alienated creatures, cut off from nature (as Wordsworth spoke of in his lyric poetry) and placed in an artificial “dead pool” that “distorts the beautiful forms of things.”

Our bodies and minds, our “science and art,” have not deviated from nature in the least.

We cannot leave the song of life.

This music made us, it is our essence.

Therefore, our ethics must be an ethics of belonging.

This ethical imperative is all the more urgent now that human actions are disrupting, reconnecting, and wearing down the world's biological web.

Therefore, to listen to trees, nature's great connectors, is to learn to dwell in relationship, in the relationship that gives life its source, its material, and its beauty. (pp. 9-10)

The belief that nature is other, a separate realm, and polluted by unnatural human traces is a denial of our own wildness.

Concrete sidewalks, the spurts of paint from a factory, and city hall documents planning Denver's growth are as natural as the rustling of maple leaves, the calls of baby woodpeckers, or the nesting of a swallow, in that they are manifestations of primates' evolved mental abilities to manipulate their environment.

Of course, whether all these natural phenomena are wise, beautiful, just and good is a separate question.

…nature does not produce dividends.

The economy of all species is contained entirely within nature.

Nature doesn't need a home.

Nature is home.

We are not deprived of nature.

Even when we are not aware of this nature, we are nature.

When we understand that we belong to this world, we develop the discernment to recognize the beautiful and the good within the human spirit, not from the outside, but from within the entangled web of life. (pp. 232-233)

The atmosphere and plants create each other.

At this time, plants are temporary crystals of carbon, and the air is a product of 400 million years of breathing forests.

Trees and air have no narrative, no telos of their own.

Because neither of them are themselves. (p. 322)

--- From the text

Publisher's Review

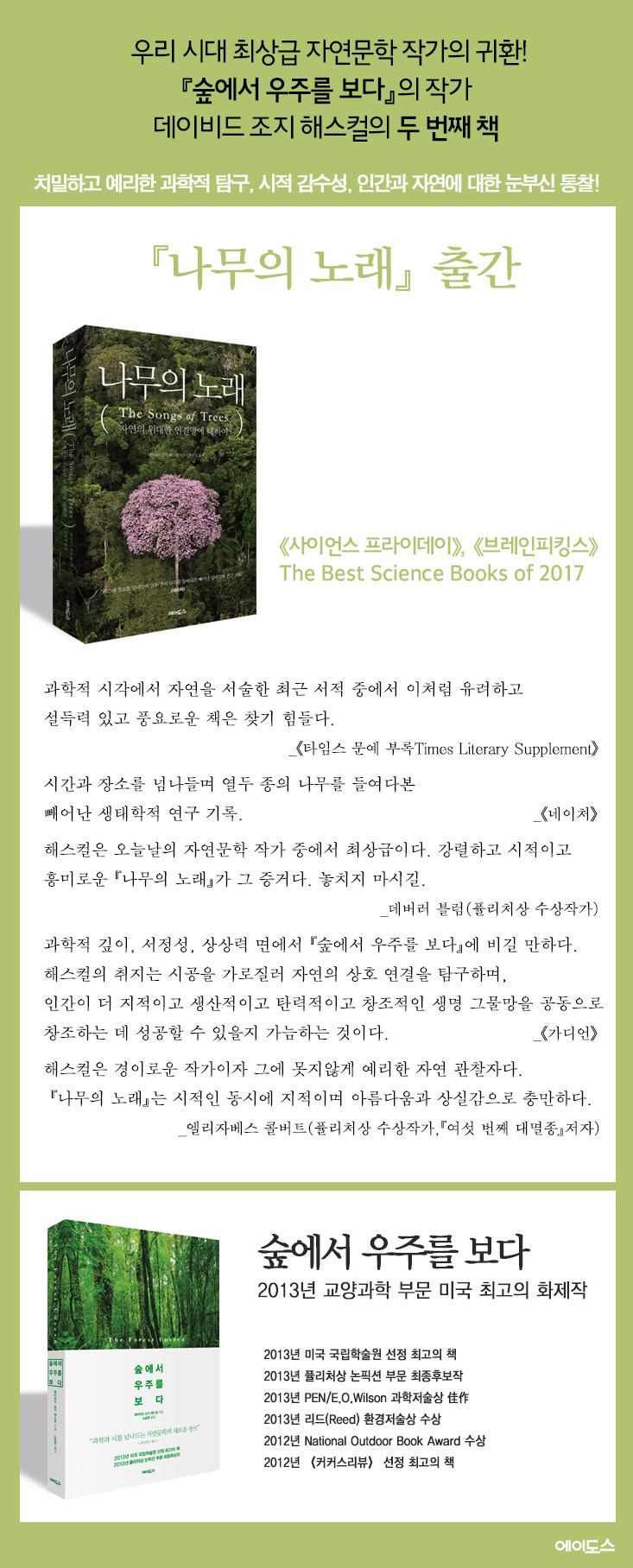

“It is difficult to find a recent book that describes nature from a scientific perspective as eloquent, persuasive, and rich as this one.”

Science Friday, Brain Pickings: The Best Science Books of 2017

The return of our time's greatest natural literature writer!

This is the second book by David George Haskell, whose "Seeing the Universe Through the Forest" was selected as a National Academy of Sciences Best Book and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

The author, who is considered one of the "best nature literature writers of our time," observed and recorded twelve species of trees from around the world, including the Amazon rainforest, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict zone, Scotland, and East Asian Japan.

It transcends time and space, describing humanity, nature, society, history, and philosophical insights in beautiful sentences.

The author's insight that humans and nature form a vast interconnected network throughout the origins and history of life leads to the search for a new ethics that transcends the individualism, ethical nihilism, and dichotomy of human versus nature in our time.

It offers poetic and elegant prose, as well as calm and meticulous scientific inquiry, and dazzling insights into humanity and nature.

Beyond the ecological record of trees, this book contains insights into humans and nature, history and culture, society and art.

This book, which was written over several years of observations and records of twelve species of trees from around the world, including the kapok trees of the Yasuni Ecological Reserve in Ecuador, the sabal palms growing on the sandy beaches of the sea, the hazel trees of Scotland, the poplars of the Denver River, the bean pear trees of downtown Manhattan, the olive trees of Israel, and the Japanese pine, is filled with the calm and keen eye of a biologist and a poetic sensibility.

The author, who “looks at nature with an open mind like a Zen monk rather than a scientist testing hypotheses” (The New York Times), climbed a ladder into the canopy of kapok trees to examine them, held a magnifying glass to a dead tree, and attached electronic equipment to a Manhattan street tree to listen to its sounds. What he discovered was a vast web of life.

Trees do not exist in isolation, but form a network of life where bacteria, fungi, plants, animals, microorganisms, and humans communicate with each other.

This web of life has continued from the birth of life hundreds of thousands of years ago to the present, forming a global community that crosses tropical rainforests, boreal forests, deserts, and temperate forests.

Naturally, humans also occupy a place in this web of life.

The charcoal from the prehistoric ovens of the Japanese cedar trees bears traces of the intimate intertwining of trees with human survival; the olive trees of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict zone have a history of coexistence with humans through numerous political conflicts and disputes since the Roman era; and the Japanese pine bonsai trees embody the artistic desire and culture of coexisting with nature.

The author goes beyond simply talking about the ecology of trees to discover a philosophy about history, culture, and humanity and nature.

Are humans the destroyers of nature, and is nature a natural space outside the human community?

Deep insights into the relationship between humans and nature

The Great Web of Life makes us reconsider the many problems left behind by the dichotomy between humans and nature.

Indeed, what are humans and what is nature in the web of life? Are human activities like destroying the Amazon rainforest for genetic development (see the chapter "Kapok Tree") and polluting the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels, carbon crystals formed over billions of years (see the chapter "Hazel Tree"), completely unrelated to nature, which we must "protect" and preserve as a "wild area"? Is nature a place polluted by unnatural human activities, a realm that exists "outside" the human community? Are the cities built by human civilization destroying biodiversity and disrupting the web of life?

What the author observed in the bean trees of Manhattan and the poplar trees of Denver was far from this.

As humans are natural, cities are also natural.

Rather, “if we think of cities as unnatural, then rivers in the city center move away from their natural state.

It's like it's okay to pour out the wastewater since it's already been 'disturbed'.

“The end result of ‘natural’ sanctuaries from which humans are excluded is an industrial dump.” (pp. 230-231) The concrete sidewalks of cities and the pollutants spewing out of factories are “as natural as the rustling of maple leaves, the calls of baby woodchucks, or the nests of tri-colored swallows, in that they all stem from the evolved mental capacities of primates.” (p. 232) Furthermore, “the high biodiversity of rural areas is due to the presence of cities, and if the world’s urban population moves into rural areas, native birds and plants will be devastated.”

Forests will be cut down, streams will turn muddy, and carbon dioxide levels will soar.' (pp. 254-255) At first glance, the author's argument about nature's great web of life seems contradictory.

However, this is a realistic perspective necessary to find solutions to contemporary environmental problems, as evidenced by the trees living in urban human communities, and also the paradoxical consequences of the dichotomous view of nature versus humans.

Nature exists for us humans as well, and human communities do not exist outside of nature.

An Ethics of Belonging Beyond Biological Atomism, Individualistic Solitude, and Ethical Nihilism

The 'human versus nature dichotomy' lies at the core of many philosophies of our time.

Biological atomism, individualism, and ethical nihilism are based on this very dichotomy.

But from a biological perspective, this dichotomy is nothing more than an 'illusion'.

This illusion is shattered by calm and meticulous biological observation, leading to an exploration of what humans can do to creatively restore the biological web.

“If we are made of the same stuff as all other living things, if our bodies arose from the same natural laws, then human actions are also natural processes.” (p. 190) Therefore, ‘the destruction and extinction of nature caused by volcanic eruptions during the Eocene is no different from climate change caused by human activities.’ Environmentalists who are worried and concerned about climate change will be puzzled.

Of course, this argument does not justify human-caused climate change or the destruction of nature caused by human activities.

Nor does it lead to ethical nihilism, where ethics and morality are merely 'illusions' created by the human nervous system.

Rather, the author argues that the idea that humans form a vast network with other living beings can serve as a starting point for discovering a "new ethics of belonging" that transcends ethical nihilism or individualistic loneliness (pp. 190-198). Because humans exist within the network of life and are members of nature, they must move beyond all actions that break and destroy the network of life and instead create a creative network of life.

Science Friday, Brain Pickings: The Best Science Books of 2017

The return of our time's greatest natural literature writer!

This is the second book by David George Haskell, whose "Seeing the Universe Through the Forest" was selected as a National Academy of Sciences Best Book and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

The author, who is considered one of the "best nature literature writers of our time," observed and recorded twelve species of trees from around the world, including the Amazon rainforest, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict zone, Scotland, and East Asian Japan.

It transcends time and space, describing humanity, nature, society, history, and philosophical insights in beautiful sentences.

The author's insight that humans and nature form a vast interconnected network throughout the origins and history of life leads to the search for a new ethics that transcends the individualism, ethical nihilism, and dichotomy of human versus nature in our time.

It offers poetic and elegant prose, as well as calm and meticulous scientific inquiry, and dazzling insights into humanity and nature.

Beyond the ecological record of trees, this book contains insights into humans and nature, history and culture, society and art.

This book, which was written over several years of observations and records of twelve species of trees from around the world, including the kapok trees of the Yasuni Ecological Reserve in Ecuador, the sabal palms growing on the sandy beaches of the sea, the hazel trees of Scotland, the poplars of the Denver River, the bean pear trees of downtown Manhattan, the olive trees of Israel, and the Japanese pine, is filled with the calm and keen eye of a biologist and a poetic sensibility.

The author, who “looks at nature with an open mind like a Zen monk rather than a scientist testing hypotheses” (The New York Times), climbed a ladder into the canopy of kapok trees to examine them, held a magnifying glass to a dead tree, and attached electronic equipment to a Manhattan street tree to listen to its sounds. What he discovered was a vast web of life.

Trees do not exist in isolation, but form a network of life where bacteria, fungi, plants, animals, microorganisms, and humans communicate with each other.

This web of life has continued from the birth of life hundreds of thousands of years ago to the present, forming a global community that crosses tropical rainforests, boreal forests, deserts, and temperate forests.

Naturally, humans also occupy a place in this web of life.

The charcoal from the prehistoric ovens of the Japanese cedar trees bears traces of the intimate intertwining of trees with human survival; the olive trees of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict zone have a history of coexistence with humans through numerous political conflicts and disputes since the Roman era; and the Japanese pine bonsai trees embody the artistic desire and culture of coexisting with nature.

The author goes beyond simply talking about the ecology of trees to discover a philosophy about history, culture, and humanity and nature.

Are humans the destroyers of nature, and is nature a natural space outside the human community?

Deep insights into the relationship between humans and nature

The Great Web of Life makes us reconsider the many problems left behind by the dichotomy between humans and nature.

Indeed, what are humans and what is nature in the web of life? Are human activities like destroying the Amazon rainforest for genetic development (see the chapter "Kapok Tree") and polluting the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels, carbon crystals formed over billions of years (see the chapter "Hazel Tree"), completely unrelated to nature, which we must "protect" and preserve as a "wild area"? Is nature a place polluted by unnatural human activities, a realm that exists "outside" the human community? Are the cities built by human civilization destroying biodiversity and disrupting the web of life?

What the author observed in the bean trees of Manhattan and the poplar trees of Denver was far from this.

As humans are natural, cities are also natural.

Rather, “if we think of cities as unnatural, then rivers in the city center move away from their natural state.

It's like it's okay to pour out the wastewater since it's already been 'disturbed'.

“The end result of ‘natural’ sanctuaries from which humans are excluded is an industrial dump.” (pp. 230-231) The concrete sidewalks of cities and the pollutants spewing out of factories are “as natural as the rustling of maple leaves, the calls of baby woodchucks, or the nests of tri-colored swallows, in that they all stem from the evolved mental capacities of primates.” (p. 232) Furthermore, “the high biodiversity of rural areas is due to the presence of cities, and if the world’s urban population moves into rural areas, native birds and plants will be devastated.”

Forests will be cut down, streams will turn muddy, and carbon dioxide levels will soar.' (pp. 254-255) At first glance, the author's argument about nature's great web of life seems contradictory.

However, this is a realistic perspective necessary to find solutions to contemporary environmental problems, as evidenced by the trees living in urban human communities, and also the paradoxical consequences of the dichotomous view of nature versus humans.

Nature exists for us humans as well, and human communities do not exist outside of nature.

An Ethics of Belonging Beyond Biological Atomism, Individualistic Solitude, and Ethical Nihilism

The 'human versus nature dichotomy' lies at the core of many philosophies of our time.

Biological atomism, individualism, and ethical nihilism are based on this very dichotomy.

But from a biological perspective, this dichotomy is nothing more than an 'illusion'.

This illusion is shattered by calm and meticulous biological observation, leading to an exploration of what humans can do to creatively restore the biological web.

“If we are made of the same stuff as all other living things, if our bodies arose from the same natural laws, then human actions are also natural processes.” (p. 190) Therefore, ‘the destruction and extinction of nature caused by volcanic eruptions during the Eocene is no different from climate change caused by human activities.’ Environmentalists who are worried and concerned about climate change will be puzzled.

Of course, this argument does not justify human-caused climate change or the destruction of nature caused by human activities.

Nor does it lead to ethical nihilism, where ethics and morality are merely 'illusions' created by the human nervous system.

Rather, the author argues that the idea that humans form a vast network with other living beings can serve as a starting point for discovering a "new ethics of belonging" that transcends ethical nihilism or individualistic loneliness (pp. 190-198). Because humans exist within the network of life and are members of nature, they must move beyond all actions that break and destroy the network of life and instead create a creative network of life.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: January 30, 2018

- Page count, weight, size: 372 pages | 473g | 142*217*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791185415185

- ISBN10: 1185415181

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)