Steven Weinberg's The Science of Explaining the World

|

Description

Book Introduction

A provocative and daring history of science like no other!

Countless moments of science's history are recreated by scientists.

Through a variety of examples, this book meticulously traces the history of science before it took on its modern form and became known as a discipline symbolizing "rational intelligence."

However, the author does not simply list historically significant theories and achievements; he attempts to engage in dialogue with scholars of the past by making full use of modern theories and knowledge.

It shows the history of science in another dimension.

In the author's hands, the history of science is reborn not as a simple record of the past, but as a grand narrative stretching toward the present.

For thousands of years, countless scholars have observed and theorized about what happens in the world.

Thanks to these efforts, modern science has been able to explain the world plausibly, but it is not yet perfect.

This means that the questions that people who tried to explain the world thousands of years ago had are still valid today.

The belief that all phenomena have a set of laws, and the effort to find these laws, continues to this day.

We are still searching for a 'final theory' that can explain all phenomena in the world.

Countless moments of science's history are recreated by scientists.

Through a variety of examples, this book meticulously traces the history of science before it took on its modern form and became known as a discipline symbolizing "rational intelligence."

However, the author does not simply list historically significant theories and achievements; he attempts to engage in dialogue with scholars of the past by making full use of modern theories and knowledge.

It shows the history of science in another dimension.

In the author's hands, the history of science is reborn not as a simple record of the past, but as a grand narrative stretching toward the present.

For thousands of years, countless scholars have observed and theorized about what happens in the world.

Thanks to these efforts, modern science has been able to explain the world plausibly, but it is not yet perfect.

This means that the questions that people who tried to explain the world thousands of years ago had are still valid today.

The belief that all phenomena have a set of laws, and the effort to find these laws, continues to this day.

We are still searching for a 'final theory' that can explain all phenomena in the world.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

Part 1: Greek Physics

Chapter 1: Matter and Time

Chapter 2 Music and Mathematics

Chapter 3: Exercise and Philosophy

Chapter 4 Physics and Technology in the Hellenistic Period

Chapter 5: Ancient Science and Religion

Part 2: Greek Astronomy

Chapter 6: The Use of Astronomy

Chapter 7: Measuring the Sun, Moon, and Earth

Chapter 8: The Problem of the Planets

Part 3: The Middle Ages

Chapter 9: The Arabs

Chapter 10 Medieval Europe

Part 4: Scientific Revolutions

Chapter 11: Unraveling the Solar System

Chapter 12: The Beginning of the Experiment

Chapter 13: A Method Reconsidered

Chapter 14 Newton's Integration

Chapter 15: The Great Simplification

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

Expert commentary

main

References

Search

Part 1: Greek Physics

Chapter 1: Matter and Time

Chapter 2 Music and Mathematics

Chapter 3: Exercise and Philosophy

Chapter 4 Physics and Technology in the Hellenistic Period

Chapter 5: Ancient Science and Religion

Part 2: Greek Astronomy

Chapter 6: The Use of Astronomy

Chapter 7: Measuring the Sun, Moon, and Earth

Chapter 8: The Problem of the Planets

Part 3: The Middle Ages

Chapter 9: The Arabs

Chapter 10 Medieval Europe

Part 4: Scientific Revolutions

Chapter 11: Unraveling the Solar System

Chapter 12: The Beginning of the Experiment

Chapter 13: A Method Reconsidered

Chapter 14 Newton's Integration

Chapter 15: The Great Simplification

Acknowledgements

Translator's Note

Expert commentary

main

References

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

Even before recorded history, something similar to science existed.

Nature has always baffled us with various phenomena.

People in the past were able to obtain useful information by observing natural phenomena such as fire, thunder and lightning, epidemics, planetary movements, light, and tides.

Fire is hot, thunder is a harbinger of rain, and the tides are greatest during the full or new moon.

But these are common sense things that everyone knows.

Everywhere there were people who wanted to know more than just the simple facts.

They were people who wanted to explain the world.

---From the "Preface"

What is even more surprising than that Parmenides and Zeno were wrong is that they did not try to explain why, if motion is impossible, objects appear to be moving.

In fact, whether in Miletus, Abdera, Elea, or Athens, none of the early Greeks, from Thales to Plato, ever addressed in detail how their theories of reality explained the appearance of things.

This wasn't because they were intellectually lazy.

The early Greeks had a kind of intellectual superiority complex that made it unworthy to understand visible phenomena.

This is just one example of the many attitudes that have marred the history of science.

---From "Chapter 1_ Matter and Poetry"

Aristotle tried to use logic rather than inspiration to justify his conclusions.

We cannot help but agree with the words of the classicist Hankinson.

“We must not lose sight of the fact that Aristotle was a man of his time.

For his time, he was unusually brilliant, radical, and forward-thinking.” Nevertheless, some of the principles underlying Aristotle’s thought had to be discarded for the sake of modern scientific discoveries.

For one thing, Aristotle's works are full of teleology.

Teleology is the theory that things are the way they are because they serve a purpose.

---From "Chapter 3_ Exercise and Philosophy"

I am convinced that scientific revolutions represent real discontinuities in the history of knowledge.

This is a judgment based on the perspective of currently active scientists.

With the exception of a few brilliant Greeks, science before the 16th century differs considerably from what I study and what I see in the work of my colleagues.

Before the Scientific Revolution, science was mixed with religion and what we now call philosophy, and was not yet connected to mathematics.

On the other hand, I feel comfortable with physics and astronomy from the 17th century onwards.

There is something very similar to science in our time.

An objective law expressed in mathematics that allows us to predict a wide range of phenomena in detail and verify these predictions by comparing them with observations or experiments.

---From "Part 4_ Scientific Revolution"

Another important difference between Hellenistic and Classical scientists is that Hellenistic scientists were less obsessed with the lofty distinction between knowledge for knowledge's sake and knowledge for use.

In fact, throughout history, many philosophers have viewed inventors in a similar light to how court official Philostrate describes Peter Quince and his weavers in A Midsummer Night's Dream.

“These are manual laborers who have never worked with their minds (heads) who are now working in Athens.” --- From “Chapter 4_ Physics and Technology in the Hellenistic Age”

What creates the distance between Aristarchus's science and modern science is not his measurement errors.

Far more serious errors have plagued observational astronomy and experimental physics for a long time.

For example, in the 1930s, the known rate at which the universe was expanding was about seven times greater than we now know the actual rate.

The real difference between Aristarchus and today's astronomers or physicists is not that his measurements were in error, but that Aristarchus never attempted to determine absolute uncertainty or acknowledged that his results might be incomplete.

---From "Chapter 7_ Measuring the Sun, Moon, and Earth"

Science had already reached its peak in the ancient world in Greece, and did not regain its position until the scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries.

The Greeks made the great discovery that some aspects of nature, especially optics and astronomy, could be described by mathematical theories that fit observations exactly.

It is important to understand light and celestial bodies, but even more important is to learn that we can understand and how to understand.

---From "Part 3_ The Middle Ages"

Still, we've come a long way along this path, and it may not be over yet.

This is a huge story.

It is the story of how celestial and terrestrial physics were unified by Newton, how a unified theory of electricity and magnetism was created to explain light, how the quantum theory of electromagnetism was extended to include the weak and strong nuclear forces, and how chemistry and biology were unified, albeit with an imperfect view of nature, based on physics.

This is a move towards more fundamental physical theories, broad scientific principles that we have discovered, which have been and are being simplified.

Nature has always baffled us with various phenomena.

People in the past were able to obtain useful information by observing natural phenomena such as fire, thunder and lightning, epidemics, planetary movements, light, and tides.

Fire is hot, thunder is a harbinger of rain, and the tides are greatest during the full or new moon.

But these are common sense things that everyone knows.

Everywhere there were people who wanted to know more than just the simple facts.

They were people who wanted to explain the world.

---From the "Preface"

What is even more surprising than that Parmenides and Zeno were wrong is that they did not try to explain why, if motion is impossible, objects appear to be moving.

In fact, whether in Miletus, Abdera, Elea, or Athens, none of the early Greeks, from Thales to Plato, ever addressed in detail how their theories of reality explained the appearance of things.

This wasn't because they were intellectually lazy.

The early Greeks had a kind of intellectual superiority complex that made it unworthy to understand visible phenomena.

This is just one example of the many attitudes that have marred the history of science.

---From "Chapter 1_ Matter and Poetry"

Aristotle tried to use logic rather than inspiration to justify his conclusions.

We cannot help but agree with the words of the classicist Hankinson.

“We must not lose sight of the fact that Aristotle was a man of his time.

For his time, he was unusually brilliant, radical, and forward-thinking.” Nevertheless, some of the principles underlying Aristotle’s thought had to be discarded for the sake of modern scientific discoveries.

For one thing, Aristotle's works are full of teleology.

Teleology is the theory that things are the way they are because they serve a purpose.

---From "Chapter 3_ Exercise and Philosophy"

I am convinced that scientific revolutions represent real discontinuities in the history of knowledge.

This is a judgment based on the perspective of currently active scientists.

With the exception of a few brilliant Greeks, science before the 16th century differs considerably from what I study and what I see in the work of my colleagues.

Before the Scientific Revolution, science was mixed with religion and what we now call philosophy, and was not yet connected to mathematics.

On the other hand, I feel comfortable with physics and astronomy from the 17th century onwards.

There is something very similar to science in our time.

An objective law expressed in mathematics that allows us to predict a wide range of phenomena in detail and verify these predictions by comparing them with observations or experiments.

---From "Part 4_ Scientific Revolution"

Another important difference between Hellenistic and Classical scientists is that Hellenistic scientists were less obsessed with the lofty distinction between knowledge for knowledge's sake and knowledge for use.

In fact, throughout history, many philosophers have viewed inventors in a similar light to how court official Philostrate describes Peter Quince and his weavers in A Midsummer Night's Dream.

“These are manual laborers who have never worked with their minds (heads) who are now working in Athens.” --- From “Chapter 4_ Physics and Technology in the Hellenistic Age”

What creates the distance between Aristarchus's science and modern science is not his measurement errors.

Far more serious errors have plagued observational astronomy and experimental physics for a long time.

For example, in the 1930s, the known rate at which the universe was expanding was about seven times greater than we now know the actual rate.

The real difference between Aristarchus and today's astronomers or physicists is not that his measurements were in error, but that Aristarchus never attempted to determine absolute uncertainty or acknowledged that his results might be incomplete.

---From "Chapter 7_ Measuring the Sun, Moon, and Earth"

Science had already reached its peak in the ancient world in Greece, and did not regain its position until the scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries.

The Greeks made the great discovery that some aspects of nature, especially optics and astronomy, could be described by mathematical theories that fit observations exactly.

It is important to understand light and celestial bodies, but even more important is to learn that we can understand and how to understand.

---From "Part 3_ The Middle Ages"

Still, we've come a long way along this path, and it may not be over yet.

This is a huge story.

It is the story of how celestial and terrestrial physics were unified by Newton, how a unified theory of electricity and magnetism was created to explain light, how the quantum theory of electromagnetism was extended to include the weak and strong nuclear forces, and how chemistry and biology were unified, albeit with an imperfect view of nature, based on physics.

This is a move towards more fundamental physical theories, broad scientific principles that we have discovered, which have been and are being simplified.

---From "Chapter 15_ The Great Simplification"

Publisher's Review

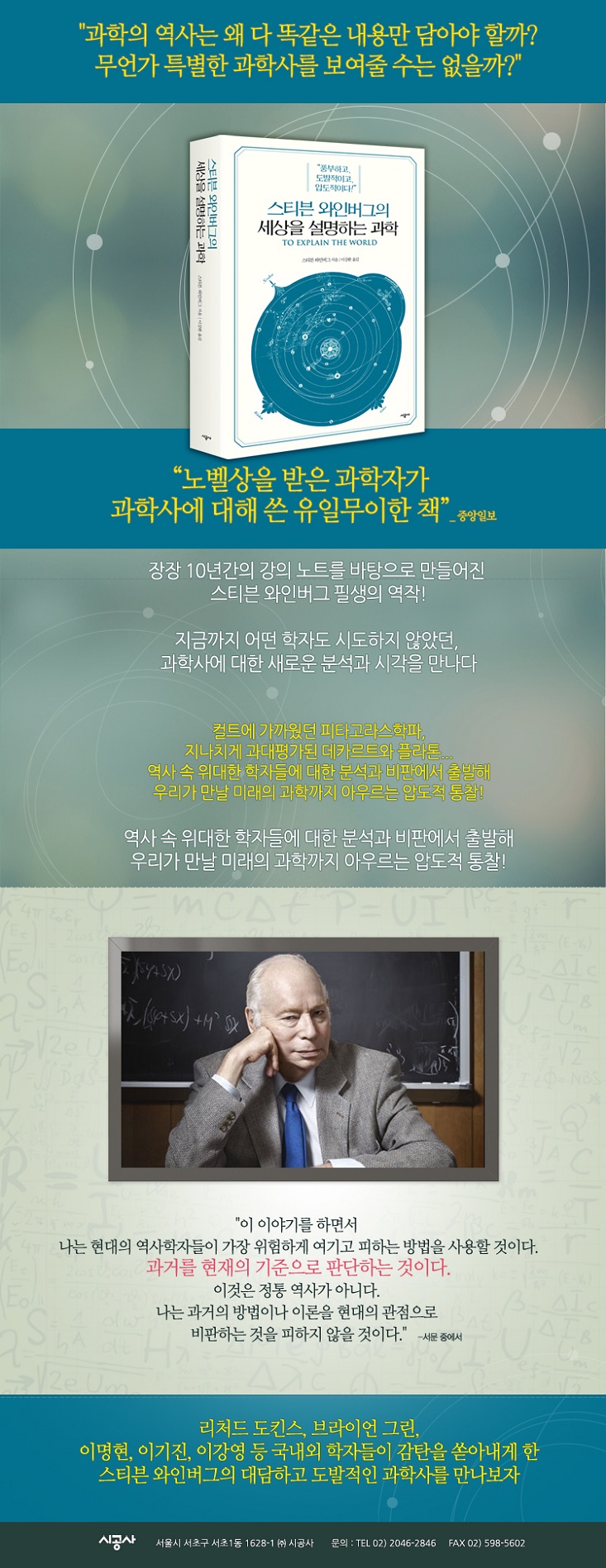

Countless moments of science's history are recreated by scientists.

Highly recommended by Richard Dawkins and Brian Greene

When did the discipline we now call "science" originate? Was it the moment Copernicus claimed the earth, not the heavens, moved? Or was it Newton's moment of life-changing insight after seeing an apple fall from a tree? What new facts did humanity discover as science advanced? When did science begin to branch out into diverse fields like physics, astronomy, and chemistry?

Any book that deals with the history of science would naturally contain such content.

But Steven Weinberg, a Nobel Prize winner in physics and world-renowned theoretical physicist, had a slightly different concern.

“Even if it is the history of science, can’t it show something other than a list of historical facts?” He volunteered to give the lecture to resolve his concerns.

It taught the history of science to students who had no background in science, history, or mathematics.

After lecturing for a full ten years, he collected the lecture notes and added his own opinions to write To Explain the World.

This book became a hot topic and a controversial work as soon as it was published.

“This is not authentic history!”

A provocative and daring history of science like no other

What made this book controversial was its perspective, which was never seen in existing books on the history of science.

The author begins the book by stating that he will “use methods that modern historians consider most dangerous and avoid,” and declares that he will judge the theories and research methods of past natural philosophers by today’s standards.

In fact, he does not hesitate to criticize great scholars and even points out in detail why their theories are wrong.

Through the 'expert commentary' included in the book, past theories are re-proven based on modern scientific knowledge.

According to the author, Aristotle's theory had some rather careless and foolish aspects.

The Pythagoreans were a cult, Descartes was overrated, and Plato's achievements were exaggerated.

We cannot help but be surprised by the author's scathing criticism.

However, the author does not take this view with the intention of disparaging the achievements of previous scholars.

The purpose was to accurately convey the role of natural philosophers in the history of science and how difficult their research was, even from the perspective of a modern scientist.

It also clearly shows how difficult it was to achieve modern science by comparing how past scientific concepts differ from present ones.

Later scholars are bound to have an advantage over their predecessors thanks to the knowledge and information they have naturally acquired over time.

However, the author does not abuse his advantageous position, but rather makes full use of modern theories and knowledge to show another dimension of the history of science.

Rather than simply listing historically significant theories or achievements, it attempted to engage in dialogue with scholars of the past.

In the author's hands, the history of science is reborn not as a simple record of the past, but as a grand narrative stretching toward the present.

Will humanity ever find a "final theory" that perfectly explains the world?

Of course, this book is faithful to historical facts to the point that it is by no means inadequate as an introduction to the history of science.

The author suggests that the origin of science was the moment in ancient Greece in the 6th century BC when people began to ponder the fundamental materials that make up the world.

Thales said that this fundamental material was water, Xenophanes said it was earth, and Heraclitus said it was fire.

Although their opinions differ, they have one thing in common.

The point is that I wanted to know more than just what I could observe in nature.

They wanted to properly 'explain' what was happening in the world, and this desire soon became the basis of science.

But early science was so imperfect.

In ancient times and the Middle Ages, there was no concept of science as something separate from philosophy.

Rather, the discipline that thought about the natural world was philosophy.

Science at that time was not as distant from religion as it is now.

For example, Plato said that natural phenomena are studied because they are examples of divinity, not because the phenomena themselves have any value.

Some scholars believed that since the earth was the domain of humans but the sky was the domain of the gods, humans would never be able to understand the movements of the celestial bodies.

Through various examples, the author meticulously traces the history of science before it took on its modern form and became known as a discipline symbolizing "rational intelligence."

The author ultimately argues that science was born and developed to explain natural phenomena whose causes remain unknown, such as the changing shape of the moon or an apple falling from a tree.

For thousands of years, countless scholars have observed and theorized about what happens in the world.

Thanks to these efforts, modern science has been able to explain the world plausibly, but it is not yet perfect.

This means that the questions that people who tried to explain the world thousands of years ago had are still valid today.

The belief that all phenomena have a set of laws, and the effort to find these laws, continues to this day.

The research methods and scientific tools have just become more modern.

We are still searching for a 'final theory' that can explain all phenomena in the world.

In this book, we see the author once again demonstrating his extensive knowledge and overwhelming insight.

It also reminds us that the "scientific mindset" we now take for granted—the scientist's emphasis on logic and objectivity and his wariness of reductionism and teleology—is a legacy built on the accumulated efforts of countless scholars over a long period of time.

Steven Weinberg's The Science of the World will completely change the way we see and understand the world.

Highly recommended by Richard Dawkins and Brian Greene

When did the discipline we now call "science" originate? Was it the moment Copernicus claimed the earth, not the heavens, moved? Or was it Newton's moment of life-changing insight after seeing an apple fall from a tree? What new facts did humanity discover as science advanced? When did science begin to branch out into diverse fields like physics, astronomy, and chemistry?

Any book that deals with the history of science would naturally contain such content.

But Steven Weinberg, a Nobel Prize winner in physics and world-renowned theoretical physicist, had a slightly different concern.

“Even if it is the history of science, can’t it show something other than a list of historical facts?” He volunteered to give the lecture to resolve his concerns.

It taught the history of science to students who had no background in science, history, or mathematics.

After lecturing for a full ten years, he collected the lecture notes and added his own opinions to write To Explain the World.

This book became a hot topic and a controversial work as soon as it was published.

“This is not authentic history!”

A provocative and daring history of science like no other

What made this book controversial was its perspective, which was never seen in existing books on the history of science.

The author begins the book by stating that he will “use methods that modern historians consider most dangerous and avoid,” and declares that he will judge the theories and research methods of past natural philosophers by today’s standards.

In fact, he does not hesitate to criticize great scholars and even points out in detail why their theories are wrong.

Through the 'expert commentary' included in the book, past theories are re-proven based on modern scientific knowledge.

According to the author, Aristotle's theory had some rather careless and foolish aspects.

The Pythagoreans were a cult, Descartes was overrated, and Plato's achievements were exaggerated.

We cannot help but be surprised by the author's scathing criticism.

However, the author does not take this view with the intention of disparaging the achievements of previous scholars.

The purpose was to accurately convey the role of natural philosophers in the history of science and how difficult their research was, even from the perspective of a modern scientist.

It also clearly shows how difficult it was to achieve modern science by comparing how past scientific concepts differ from present ones.

Later scholars are bound to have an advantage over their predecessors thanks to the knowledge and information they have naturally acquired over time.

However, the author does not abuse his advantageous position, but rather makes full use of modern theories and knowledge to show another dimension of the history of science.

Rather than simply listing historically significant theories or achievements, it attempted to engage in dialogue with scholars of the past.

In the author's hands, the history of science is reborn not as a simple record of the past, but as a grand narrative stretching toward the present.

Will humanity ever find a "final theory" that perfectly explains the world?

Of course, this book is faithful to historical facts to the point that it is by no means inadequate as an introduction to the history of science.

The author suggests that the origin of science was the moment in ancient Greece in the 6th century BC when people began to ponder the fundamental materials that make up the world.

Thales said that this fundamental material was water, Xenophanes said it was earth, and Heraclitus said it was fire.

Although their opinions differ, they have one thing in common.

The point is that I wanted to know more than just what I could observe in nature.

They wanted to properly 'explain' what was happening in the world, and this desire soon became the basis of science.

But early science was so imperfect.

In ancient times and the Middle Ages, there was no concept of science as something separate from philosophy.

Rather, the discipline that thought about the natural world was philosophy.

Science at that time was not as distant from religion as it is now.

For example, Plato said that natural phenomena are studied because they are examples of divinity, not because the phenomena themselves have any value.

Some scholars believed that since the earth was the domain of humans but the sky was the domain of the gods, humans would never be able to understand the movements of the celestial bodies.

Through various examples, the author meticulously traces the history of science before it took on its modern form and became known as a discipline symbolizing "rational intelligence."

The author ultimately argues that science was born and developed to explain natural phenomena whose causes remain unknown, such as the changing shape of the moon or an apple falling from a tree.

For thousands of years, countless scholars have observed and theorized about what happens in the world.

Thanks to these efforts, modern science has been able to explain the world plausibly, but it is not yet perfect.

This means that the questions that people who tried to explain the world thousands of years ago had are still valid today.

The belief that all phenomena have a set of laws, and the effort to find these laws, continues to this day.

The research methods and scientific tools have just become more modern.

We are still searching for a 'final theory' that can explain all phenomena in the world.

In this book, we see the author once again demonstrating his extensive knowledge and overwhelming insight.

It also reminds us that the "scientific mindset" we now take for granted—the scientist's emphasis on logic and objectivity and his wariness of reductionism and teleology—is a legacy built on the accumulated efforts of countless scholars over a long period of time.

Steven Weinberg's The Science of the World will completely change the way we see and understand the world.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of publication: August 29, 2016

- Page count, weight, size: 496 pages | 837g | 153*224*27mm

- ISBN13: 9788952776822

- ISBN10: 8952776828

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)