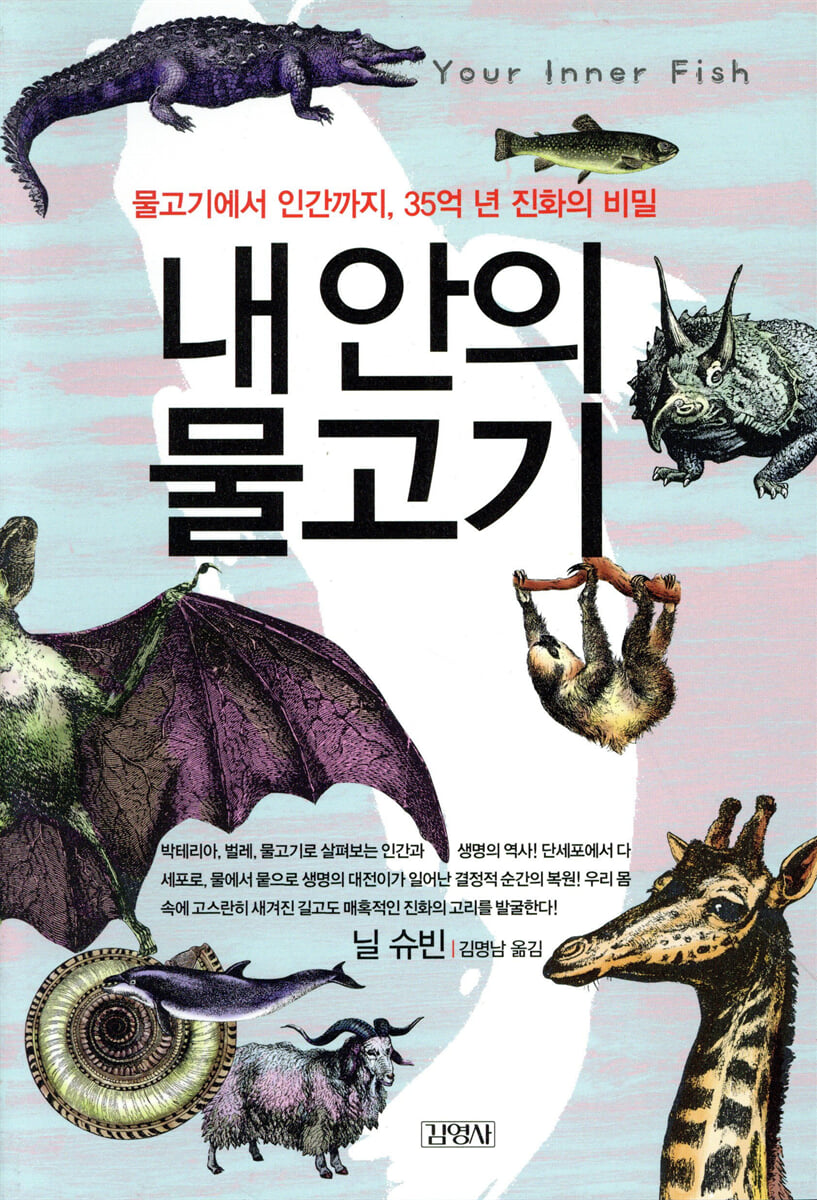

The fish inside me

|

Description

Book Introduction

Neil Shubin, a world-renowned paleontologist who surprised the academic world with the discovery of the legged fish 'Tiktaalik', traces the history of the human body from the bodies of seemingly unrelated creatures such as fish, flies, and bacteria.

The ultimate question pursued by biology and evolution is how the human body was created and why it is shaped this way.

Because, along with the genuine desire to discover our own identity, the answers can reveal why our bodies break down in certain ways.

This book unravels the mystery of human evolution through the fossil of a footed fish discovered on Ellesmere Island in the Arctic in 2004.

The author suggests two paths to find the answer: 'Fossils and Paleontology' and 'DNA and Evolutionary Developmental Biology'. By examining fossils and DNA, he cites various pieces of evidence and reveals that the anatomical structures of our bodies, fish, reptiles, and other creatures are surprisingly similar.

That is, it proves that human hands resemble fish fins, the human head is organized like the head of a long-extinct jawless fish, and the human genome functions similarly to the genome of bacteria.

Life has existed on Earth for 3.5 billion years, and this long and fascinating history is embedded in the structure of our bodies.

Neil Shubin, who claims that "humans are upgraded fish," presents a fascinating account of the evolutionary journey from single-celled to multi-cellular and from water to land in this book.

The ultimate question pursued by biology and evolution is how the human body was created and why it is shaped this way.

Because, along with the genuine desire to discover our own identity, the answers can reveal why our bodies break down in certain ways.

This book unravels the mystery of human evolution through the fossil of a footed fish discovered on Ellesmere Island in the Arctic in 2004.

The author suggests two paths to find the answer: 'Fossils and Paleontology' and 'DNA and Evolutionary Developmental Biology'. By examining fossils and DNA, he cites various pieces of evidence and reveals that the anatomical structures of our bodies, fish, reptiles, and other creatures are surprisingly similar.

That is, it proves that human hands resemble fish fins, the human head is organized like the head of a long-extinct jawless fish, and the human genome functions similarly to the genome of bacteria.

Life has existed on Earth for 3.5 billion years, and this long and fascinating history is embedded in the structure of our bodies.

Neil Shubin, who claims that "humans are upgraded fish," presents a fascinating account of the evolutionary journey from single-celled to multi-cellular and from water to land in this book.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Before reading this book

preface

Chapter 1: Finding the Fish Within Me

Evidence of evolution: fossils

Finding the missing puzzle piece

Chapter 2 The Fish with Wrists

A single pattern that makes up the hand and arm

Fish Push-ups

From the 3rd fin to the hand

The genes that make up hands

Give a shark a hand

Chapter 4: There are teeth everywhere

Before we had our incisors, canines, and molars

Why do teeth and bones harden?

Teeth, feathers, and scales all started from one.

Chapter 5: The Origin of the Human Head

confusion in the head

Gill arches and cranial nerves

The shark inside me

The head had a shabby start

Chapter 6 Optimal Body Design

common blueprint

embryo experiments

Paris and Man

DNA and organisms

The malmijal inside me

Chapter 7: The Birth of the Body

Conditions for becoming a body

Dig up the first body

Between cells

The simplest bodies on Earth

The optimal environment for the birth of the body

Chapter 8: Nose and Smell

Binding of odor molecules and olfactory neurons

The Secrets Revealed by Olfactory Genes

Chapter 9: Eyes and Views

photoreceptor molecules that collect light

The tissue that connects insects and human eyes

The Secret of Mutant Genes

Chapter 10 and Listening

Middle ear from the jawbone of a reptile

The inner ear where the gel moves and the hair bends

The origin of eyes and ears: jellyfish

Chapter 11: Listening to the Fish Within Me

The zoo inside me

A walk around the zoo

How History Hurts Us

Conclusion

After the publication of “The Fish Inside Me”

Recommended materials

Acknowledgements

Search

preface

Chapter 1: Finding the Fish Within Me

Evidence of evolution: fossils

Finding the missing puzzle piece

Chapter 2 The Fish with Wrists

A single pattern that makes up the hand and arm

Fish Push-ups

From the 3rd fin to the hand

The genes that make up hands

Give a shark a hand

Chapter 4: There are teeth everywhere

Before we had our incisors, canines, and molars

Why do teeth and bones harden?

Teeth, feathers, and scales all started from one.

Chapter 5: The Origin of the Human Head

confusion in the head

Gill arches and cranial nerves

The shark inside me

The head had a shabby start

Chapter 6 Optimal Body Design

common blueprint

embryo experiments

Paris and Man

DNA and organisms

The malmijal inside me

Chapter 7: The Birth of the Body

Conditions for becoming a body

Dig up the first body

Between cells

The simplest bodies on Earth

The optimal environment for the birth of the body

Chapter 8: Nose and Smell

Binding of odor molecules and olfactory neurons

The Secrets Revealed by Olfactory Genes

Chapter 9: Eyes and Views

photoreceptor molecules that collect light

The tissue that connects insects and human eyes

The Secret of Mutant Genes

Chapter 10 and Listening

Middle ear from the jawbone of a reptile

The inner ear where the gel moves and the hair bends

The origin of eyes and ears: jellyfish

Chapter 11: Listening to the Fish Within Me

The zoo inside me

A walk around the zoo

How History Hurts Us

Conclusion

After the publication of “The Fish Inside Me”

Recommended materials

Acknowledgements

Search

Into the book

Find the fish inside me

There is no field guide to Arctic paleontology.

Friends and colleagues recommended all sorts of gear, and we read a lot of reference books, but we felt completely unprepared for the experience ahead.

The moment I realized this most painfully was when the helicopter first landed us in some remote part of the Arctic.

The first thing that came to mind was a polar bear.

And countless times I looked around, watching for any movement of a whitish speck.

When you suffer from anxiety, you start seeing hallucinations.

During the first week of work in the Arctic, one of the expedition members noticed a white blob moving around.

It seemed like there was a polar bear 0.4 kilometers away.

We scrambled to grab our guns, flares, and whistles like some silly cops from a 1920s silent movie, but on closer inspection, we realized the bear was a white Arctic hare, standing about 20 feet away.

In the North Pole, there are no trees or houses to judge distance, so you lose your sense of perspective.

The Arctic is a vast and empty space.

The rocks we were interested in were exposed for a whopping 1,500 kilometers.

On the other hand, the creature we were looking for was about 1.2 meters long.

Somehow, I had to pinpoint the small lump of rock that would preserve the fossil.

The people who review research grant applications are incredibly picky, so they bring up these difficulties like ghosts.

A committee member who previously reviewed Parish's Arctic expedition grant application made a striking statement:

To paraphrase the judges' comments (which, let's face it, were not very positive), the odds of finding new fossils in the Arctic are "lower than finding a needle in a haystack."

We only found our needle after exploring Ellesmere Island four times over six years.

That's what luck is.

Pages 38-39

A single pattern that makes up the hand and arm

There is a certain pattern to the human arm skeleton.

That is, there is one bone in the upper arm, two bones in the forearm, and nine small bones in the wrist, from which five branches extend to form the fingers.

The arrangement of human leg bones is similar to this.

One bone, two bones, several round bones, five toes.

Owen compared this pattern to various animal skeletons around the world and discovered something surprising.

He did not focus on the differences that make the various skeletons different from each other.

That was Owen's genius.

Owen discovered surprising similarities between creatures as disparate as frogs and humans, and he preached this fact in lectures and books.

The limbs of all living things follow a common design.

It doesn't matter whether the limbs are wings, webbed feet, or hands.

First, there is one bone, such as the humerus in the arm or the femur in the thigh, then two bones are connected to it by joints, then several small, round bones are attached to it, and finally, the fingers or toes are connected.

This pattern underlies the structure of all limbs.

Want to make bat wings? Just stretch your fingers out really long.

Want to make a horse? Just lengthen the middle finger and toes and shorten or eliminate the rest.

So what about frog legs? Just take the leg bones, stretch them, and then fuse them together into a single mass.

Differences between living things lie in the shape and size of their bones, and in the number of round bones or fingers and toes.

Although the shape and function of the limbs may be drastically different, the underlying blueprint is always the same.

Pages 57-58

There are teeth everywhere

If teeth had never developed in the first place, there would never have been scales, feathers, or breasts.

This is because the tools used to create skin structures are modified versions of teeth-forming tools.

Teeth, feathers, and breasts may seem like unrelated organs, but in a deep sense, they are intertwined in a single history.

So far, we have discussed the topic of how to track a single organ in various organisms.

Chapter 1 discusses how we can find deformed versions of human organs in ancient rocks and even predict such excavations.

Chapter 2 discussed the existence of similar bones in all animals, from fish to humans.

In Chapter 3, we discussed that the genetic recipes that direct organ formation among the DNA passed down from organism to offspring are generally similar regardless of the type of organism.

In Chapter 4, we saw that there is a consistent theme that runs through teeth, mammary glands, and feathers.

The biological processes that create different organs are actually variations of one process.

Given the profound similarities between various organs and bodies, the various creatures of the world are merely variations on a single theme.

Page 132

The origin of the human head

There is one more thing that humans and these little bugs have in common.

It's the gill palace.

Each arch corresponds to a small cartilaginous ridge, and like the cartilage that forms part of the human jaw, ear bones, and larynx, the cartilaginous ridges of crucian cartilages support the gill slits.

So, the essence of the human head can be traced back to that of an insect.

And that too, as a headless bug.

Page 154

Conditions for becoming a body

When our distant ancestors evolved from single-celled organisms to become living organisms with bodies, their cells would have had to learn new cooperative mechanisms.

Actually, that happened a billion years ago.

Cells needed to communicate with each other, combine in new ways, and create new materials.

For example, we had to know how to create molecules that would give each organ its own unique characteristics.

So the glue that holds cells together, the way they 'speak' to each other, the way they make special molecules—these properties are key extensions of the toolbox needed to build every body on Earth.

The invention of these tools was nothing short of revolutionary.

When single-celled animals transformed into animals with bodies, a whole new world opened up.

New creatures with new talents have appeared.

Organisms grew larger, became able to move around, and developed new organs for sensing, eating, and digesting.

Page 186

The past of the fish and tadpole that caused hiccups

The problem is that the brainstem was originally used to control the fish's breathing.

After some modification, it came to control the breathing of mammals.

Sharks and bony fish also have areas in their brainstems that provide rhythmic movement to the muscles around the throat and gills.

Nerves from that area control the neck and gill areas.

This type of neural arrangement has been observed even in the most primitive fossil fish.

Among the fossils of armored fish found in rocks from 400 million years ago, there are some with brains and cranial nerves preserved as cast fossils, and looking at them, we can see that the nerves that control breathing are coming out of the brainstem, just like in modern fish.

This structure may work well for fish, but it is truly annoying for mammals.

In fish, the nerves that control breathing do not have to travel very far from the brainstem.

This is because the gills and throat usually surround the brainstem.

But mammals are different.

Breathing in mammals is controlled by the muscles of the chest wall and the diaphragm, a membrane-like muscle that separates the chest from the abdomen.

The diaphragm contracts to control inhalation, and the nerves that control the diaphragm come from the brain.

As in fish, these are the vagus nerve and the phrenic nerve, which come out of the brainstem near the neck.

The two nerves that extend from beneath the skull must pass through the rib cage before reaching the chest area and diaphragm, which control breathing.

Following such a twisted path is bound to lead to problems.

In a rational design, the nerves should emerge near the diaphragm rather than in the neck, but unfortunately that is not the case.

So while the nerves are making their long journey, something can occasionally interfere with their function and cause them to spasm.

Pages 289-290

The shark's past as a cause of hernias

The reason why humans are prone to hernias is because they created the mammalian body by kneading the body of a fish.

At least that's the case with hernias in the inguinal area.

The gonads of fish extend to the upper chest, almost close to the heart, but this is not the case in mammals.

That's the problem.

Of course, it's a good thing that the human gonads aren't in the chest, near the heart (if they were, it would be a weird feeling every time we pledge our allegiance to the flag).

If our gonads were in our chests, we might not be able to reproduce.

Page 292

There is no field guide to Arctic paleontology.

Friends and colleagues recommended all sorts of gear, and we read a lot of reference books, but we felt completely unprepared for the experience ahead.

The moment I realized this most painfully was when the helicopter first landed us in some remote part of the Arctic.

The first thing that came to mind was a polar bear.

And countless times I looked around, watching for any movement of a whitish speck.

When you suffer from anxiety, you start seeing hallucinations.

During the first week of work in the Arctic, one of the expedition members noticed a white blob moving around.

It seemed like there was a polar bear 0.4 kilometers away.

We scrambled to grab our guns, flares, and whistles like some silly cops from a 1920s silent movie, but on closer inspection, we realized the bear was a white Arctic hare, standing about 20 feet away.

In the North Pole, there are no trees or houses to judge distance, so you lose your sense of perspective.

The Arctic is a vast and empty space.

The rocks we were interested in were exposed for a whopping 1,500 kilometers.

On the other hand, the creature we were looking for was about 1.2 meters long.

Somehow, I had to pinpoint the small lump of rock that would preserve the fossil.

The people who review research grant applications are incredibly picky, so they bring up these difficulties like ghosts.

A committee member who previously reviewed Parish's Arctic expedition grant application made a striking statement:

To paraphrase the judges' comments (which, let's face it, were not very positive), the odds of finding new fossils in the Arctic are "lower than finding a needle in a haystack."

We only found our needle after exploring Ellesmere Island four times over six years.

That's what luck is.

Pages 38-39

A single pattern that makes up the hand and arm

There is a certain pattern to the human arm skeleton.

That is, there is one bone in the upper arm, two bones in the forearm, and nine small bones in the wrist, from which five branches extend to form the fingers.

The arrangement of human leg bones is similar to this.

One bone, two bones, several round bones, five toes.

Owen compared this pattern to various animal skeletons around the world and discovered something surprising.

He did not focus on the differences that make the various skeletons different from each other.

That was Owen's genius.

Owen discovered surprising similarities between creatures as disparate as frogs and humans, and he preached this fact in lectures and books.

The limbs of all living things follow a common design.

It doesn't matter whether the limbs are wings, webbed feet, or hands.

First, there is one bone, such as the humerus in the arm or the femur in the thigh, then two bones are connected to it by joints, then several small, round bones are attached to it, and finally, the fingers or toes are connected.

This pattern underlies the structure of all limbs.

Want to make bat wings? Just stretch your fingers out really long.

Want to make a horse? Just lengthen the middle finger and toes and shorten or eliminate the rest.

So what about frog legs? Just take the leg bones, stretch them, and then fuse them together into a single mass.

Differences between living things lie in the shape and size of their bones, and in the number of round bones or fingers and toes.

Although the shape and function of the limbs may be drastically different, the underlying blueprint is always the same.

Pages 57-58

There are teeth everywhere

If teeth had never developed in the first place, there would never have been scales, feathers, or breasts.

This is because the tools used to create skin structures are modified versions of teeth-forming tools.

Teeth, feathers, and breasts may seem like unrelated organs, but in a deep sense, they are intertwined in a single history.

So far, we have discussed the topic of how to track a single organ in various organisms.

Chapter 1 discusses how we can find deformed versions of human organs in ancient rocks and even predict such excavations.

Chapter 2 discussed the existence of similar bones in all animals, from fish to humans.

In Chapter 3, we discussed that the genetic recipes that direct organ formation among the DNA passed down from organism to offspring are generally similar regardless of the type of organism.

In Chapter 4, we saw that there is a consistent theme that runs through teeth, mammary glands, and feathers.

The biological processes that create different organs are actually variations of one process.

Given the profound similarities between various organs and bodies, the various creatures of the world are merely variations on a single theme.

Page 132

The origin of the human head

There is one more thing that humans and these little bugs have in common.

It's the gill palace.

Each arch corresponds to a small cartilaginous ridge, and like the cartilage that forms part of the human jaw, ear bones, and larynx, the cartilaginous ridges of crucian cartilages support the gill slits.

So, the essence of the human head can be traced back to that of an insect.

And that too, as a headless bug.

Page 154

Conditions for becoming a body

When our distant ancestors evolved from single-celled organisms to become living organisms with bodies, their cells would have had to learn new cooperative mechanisms.

Actually, that happened a billion years ago.

Cells needed to communicate with each other, combine in new ways, and create new materials.

For example, we had to know how to create molecules that would give each organ its own unique characteristics.

So the glue that holds cells together, the way they 'speak' to each other, the way they make special molecules—these properties are key extensions of the toolbox needed to build every body on Earth.

The invention of these tools was nothing short of revolutionary.

When single-celled animals transformed into animals with bodies, a whole new world opened up.

New creatures with new talents have appeared.

Organisms grew larger, became able to move around, and developed new organs for sensing, eating, and digesting.

Page 186

The past of the fish and tadpole that caused hiccups

The problem is that the brainstem was originally used to control the fish's breathing.

After some modification, it came to control the breathing of mammals.

Sharks and bony fish also have areas in their brainstems that provide rhythmic movement to the muscles around the throat and gills.

Nerves from that area control the neck and gill areas.

This type of neural arrangement has been observed even in the most primitive fossil fish.

Among the fossils of armored fish found in rocks from 400 million years ago, there are some with brains and cranial nerves preserved as cast fossils, and looking at them, we can see that the nerves that control breathing are coming out of the brainstem, just like in modern fish.

This structure may work well for fish, but it is truly annoying for mammals.

In fish, the nerves that control breathing do not have to travel very far from the brainstem.

This is because the gills and throat usually surround the brainstem.

But mammals are different.

Breathing in mammals is controlled by the muscles of the chest wall and the diaphragm, a membrane-like muscle that separates the chest from the abdomen.

The diaphragm contracts to control inhalation, and the nerves that control the diaphragm come from the brain.

As in fish, these are the vagus nerve and the phrenic nerve, which come out of the brainstem near the neck.

The two nerves that extend from beneath the skull must pass through the rib cage before reaching the chest area and diaphragm, which control breathing.

Following such a twisted path is bound to lead to problems.

In a rational design, the nerves should emerge near the diaphragm rather than in the neck, but unfortunately that is not the case.

So while the nerves are making their long journey, something can occasionally interfere with their function and cause them to spasm.

Pages 289-290

The shark's past as a cause of hernias

The reason why humans are prone to hernias is because they created the mammalian body by kneading the body of a fish.

At least that's the case with hernias in the inguinal area.

The gonads of fish extend to the upper chest, almost close to the heart, but this is not the case in mammals.

That's the problem.

Of course, it's a good thing that the human gonads aren't in the chest, near the heart (if they were, it would be a weird feeling every time we pledge our allegiance to the flag).

If our gonads were in our chests, we might not be able to reproduce.

Page 292

--- From the text

Publisher's Review

The history of humans and life through bacteria, bugs, and fish!

Restoration of the crucial moment when life transitioned from unicellular to multicellular and from water to land!

Discover the links of evolution engraved within our bodies!

Humans are upgraded fish?!

Neil Shubin, a world-renowned paleontologist who stunned the academic world with the discovery of the legged fish "Tiktaalik," traces the history of the human body! Why is the human body shaped this way? The origins of the human body discovered in fish! Hiccups and hernias are evidence of human evolutionary "upgrades" from fish!

How was the human body formed? Through what process, and why was it shaped this way? These are the ultimate questions pursued by biology and evolution.

Because, along with the genuine desire to discover our own identity, the answers can reveal why our bodies break down in certain ways.

According to The Fish Inside Me, the answer lies within the bodies of other animals.

And it's not in the bodies of chimpanzees, whose genes are 99.7 percent identical to ours, but in the bodies of creatures that seem unrelated to us, such as fish, flies, and bacteria!

The fish inside me, me inside the fish

In 2004, a fossil of a fish with legs was discovered on Ellesmere Island in the Arctic.

It is Tiktaalik, which lived on Earth 375 million years ago.

Tiktaalik was evidence of the evolution of life from fish to amphibians, and from water to land.

When Tiktaalik was announced to the world in 2006, just two years after its discovery, the paleontological world was turned upside down.

Articles announcing the discovery of a "missing link in evolution" made the front pages of newspapers around the world, and heated discussions continued day after day on various science blogs.

Professor Neil Shubin of the University of Chicago, who discovered Tiktaalik, explains the significance of Tiktaalik's existence in his book, The Fish Within:

“What we found was a beautiful fossil that was an intermediate stage between fish and terrestrial animals.

This guy has scales on his back and webbed fins like a fish.

However, like early terrestrial animals, it had a flat head and neck.

Also, if you look inside the webbed fins, you will see that they have upper and lower arms, and even bones and joints corresponding to wrists.

The origins of human limb structure can largely be traced back to the fins of these 'footed fish'.

Try bending your wrist in and out or making a fist.

The joints used to perform these movements did not exist before Tiktaalik appeared.

After Tiktaalik, these joints were always present in the limbs of animals.

Well, now we come to a clear realization of one fact.

The first creatures to have human humerus, forearm, wrist and palm also had scales and webbed feet.

“That creature was definitely a fish!”

Along the evolutionary journey to the human body

How can we find clues to the evolution of the human body in the bodies of other animals? Neil Shubin guides us along two paths.

One path is the path of fossils and paleontology.

Fossils are visible evidence proving the hypothesis that our distant ancestors emerged from water onto land, became tetrapods, and further evolved to acquire specialized body structures and sensory organs.

The other path is the path of DNA and evolutionary developmental biology.

The genes that form the bodies of modern organisms have existed for a very long time, and many parts are common even among different species.

That is, life has created such a variety of bodies by using old tools (genes) in various ways.

The Fish Within is a fascinating introduction to how paleontology and developmental genetics can be used to understand our past, present, and future.

Humans are much closer to other creatures than we think.

This book uses evidence from paleontology and genetics to demonstrate that the anatomy of our bodies, fish, reptiles, and other creatures is remarkably similar.

Life has existed on Earth for 3.5 billion years, and this long and fascinating history is embedded in the structure of our bodies.

If you want to understand the origins of humanity, this book is a must-read.

By examining fossils and DNA, Neil Shubin proves that human hands really do resemble fish fins, that the human head is organized like the heads of long-extinct jawless fish, and that the human genome functions similarly to the genome of bacteria.

He even goes so far as to say, “Humans are upgraded fish.”

But what's even more interesting is that because humans are using the fish's body structure with some modifications, they end up experiencing hiccups, hernias, sleep apnea, and more.

Upgraded fish, but there are problems

People have special talents such as speaking, thinking, grasping, and walking on two feet, but they have to pay a reasonable price for these talents.

It was an inevitable result, as the genealogy of life remained intact within the human body.

In a perfectly designed world, a world without evolutionary history, we humans would not suffer from diseases ranging from hemorrhoids to cancer.

The best visual representation of the history of human evolution is our twisted and convoluted arteries, veins, and nerves.

Let's pick any nerve and follow its path.

It will undoubtedly wind its way around the internal organs along strange, winding paths, going in one direction only to turn for no apparent reason and end up in unexpected places.

If you were to attach arms and legs to a fish's body and make it stand up and walk on two feet, that would be the only way to do it.

Because of this, problems sometimes arise.

For example, problems such as hiccups or hernias.

There are countless other ways in which the past haunts us.

What does the history of billions of years of life mean for our lives today? We are beginning to dimly grasp the answer to science's greatest mystery: the difference between humans and other life forms.

We have learned how the human body works, what causes the diseases we suffer from, and we have been able to develop tools that can help us live longer and healthier lives.

Could there be a more beautiful and intellectually profound task than to discover the origins of humanity and find solutions to human ailments through the humblest creatures that have ever lived on Earth?

Restoration of the crucial moment when life transitioned from unicellular to multicellular and from water to land!

Discover the links of evolution engraved within our bodies!

Humans are upgraded fish?!

Neil Shubin, a world-renowned paleontologist who stunned the academic world with the discovery of the legged fish "Tiktaalik," traces the history of the human body! Why is the human body shaped this way? The origins of the human body discovered in fish! Hiccups and hernias are evidence of human evolutionary "upgrades" from fish!

How was the human body formed? Through what process, and why was it shaped this way? These are the ultimate questions pursued by biology and evolution.

Because, along with the genuine desire to discover our own identity, the answers can reveal why our bodies break down in certain ways.

According to The Fish Inside Me, the answer lies within the bodies of other animals.

And it's not in the bodies of chimpanzees, whose genes are 99.7 percent identical to ours, but in the bodies of creatures that seem unrelated to us, such as fish, flies, and bacteria!

The fish inside me, me inside the fish

In 2004, a fossil of a fish with legs was discovered on Ellesmere Island in the Arctic.

It is Tiktaalik, which lived on Earth 375 million years ago.

Tiktaalik was evidence of the evolution of life from fish to amphibians, and from water to land.

When Tiktaalik was announced to the world in 2006, just two years after its discovery, the paleontological world was turned upside down.

Articles announcing the discovery of a "missing link in evolution" made the front pages of newspapers around the world, and heated discussions continued day after day on various science blogs.

Professor Neil Shubin of the University of Chicago, who discovered Tiktaalik, explains the significance of Tiktaalik's existence in his book, The Fish Within:

“What we found was a beautiful fossil that was an intermediate stage between fish and terrestrial animals.

This guy has scales on his back and webbed fins like a fish.

However, like early terrestrial animals, it had a flat head and neck.

Also, if you look inside the webbed fins, you will see that they have upper and lower arms, and even bones and joints corresponding to wrists.

The origins of human limb structure can largely be traced back to the fins of these 'footed fish'.

Try bending your wrist in and out or making a fist.

The joints used to perform these movements did not exist before Tiktaalik appeared.

After Tiktaalik, these joints were always present in the limbs of animals.

Well, now we come to a clear realization of one fact.

The first creatures to have human humerus, forearm, wrist and palm also had scales and webbed feet.

“That creature was definitely a fish!”

Along the evolutionary journey to the human body

How can we find clues to the evolution of the human body in the bodies of other animals? Neil Shubin guides us along two paths.

One path is the path of fossils and paleontology.

Fossils are visible evidence proving the hypothesis that our distant ancestors emerged from water onto land, became tetrapods, and further evolved to acquire specialized body structures and sensory organs.

The other path is the path of DNA and evolutionary developmental biology.

The genes that form the bodies of modern organisms have existed for a very long time, and many parts are common even among different species.

That is, life has created such a variety of bodies by using old tools (genes) in various ways.

The Fish Within is a fascinating introduction to how paleontology and developmental genetics can be used to understand our past, present, and future.

Humans are much closer to other creatures than we think.

This book uses evidence from paleontology and genetics to demonstrate that the anatomy of our bodies, fish, reptiles, and other creatures is remarkably similar.

Life has existed on Earth for 3.5 billion years, and this long and fascinating history is embedded in the structure of our bodies.

If you want to understand the origins of humanity, this book is a must-read.

By examining fossils and DNA, Neil Shubin proves that human hands really do resemble fish fins, that the human head is organized like the heads of long-extinct jawless fish, and that the human genome functions similarly to the genome of bacteria.

He even goes so far as to say, “Humans are upgraded fish.”

But what's even more interesting is that because humans are using the fish's body structure with some modifications, they end up experiencing hiccups, hernias, sleep apnea, and more.

Upgraded fish, but there are problems

People have special talents such as speaking, thinking, grasping, and walking on two feet, but they have to pay a reasonable price for these talents.

It was an inevitable result, as the genealogy of life remained intact within the human body.

In a perfectly designed world, a world without evolutionary history, we humans would not suffer from diseases ranging from hemorrhoids to cancer.

The best visual representation of the history of human evolution is our twisted and convoluted arteries, veins, and nerves.

Let's pick any nerve and follow its path.

It will undoubtedly wind its way around the internal organs along strange, winding paths, going in one direction only to turn for no apparent reason and end up in unexpected places.

If you were to attach arms and legs to a fish's body and make it stand up and walk on two feet, that would be the only way to do it.

Because of this, problems sometimes arise.

For example, problems such as hiccups or hernias.

There are countless other ways in which the past haunts us.

What does the history of billions of years of life mean for our lives today? We are beginning to dimly grasp the answer to science's greatest mystery: the difference between humans and other life forms.

We have learned how the human body works, what causes the diseases we suffer from, and we have been able to develop tools that can help us live longer and healthier lives.

Could there be a more beautiful and intellectually profound task than to discover the origins of humanity and find solutions to human ailments through the humblest creatures that have ever lived on Earth?

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 8, 2009

- Page count, weight, size: 346 pages | 462g | 148*210*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788934934660

- ISBN10: 8934934662

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)