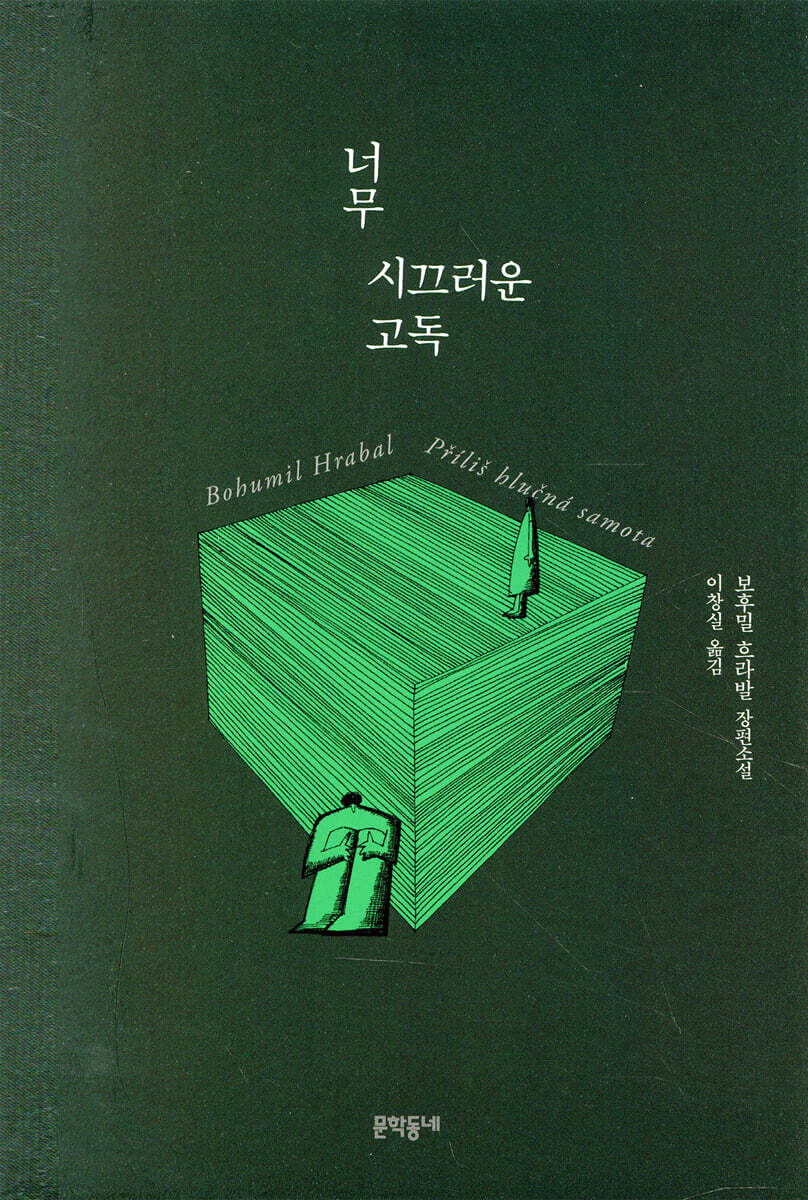

Too noisy loneliness

|

Description

Book Introduction

“I, who have been engrossed in type for thirty-five years, compressing books and waste paper,

“It ended up looking just like the books I’ve been compressing with my own hands!”

In the loneliness of a desperate and noisy world

A fiery monologue from an old dreamer who dreamed of existential liberation!

Czech national author Bohumil Hrabal's masterpiece, "Too Loud in Solitude," has been published by Munhakdongne.

Bohumil Hrabal is considered one of the most representative Czech writers, along with Milan Kundera, after Franz Kafka.

He is sometimes called the 'sad king of Czech novels' by foreign media and writers, because while many writers, including Milan Kundera, went into exile in France and other countries after the 'Prague Spring' and wrote in French, he remained in the Czech Republic and wrote in Czech until the end.

So, although his name is not widely known in Korea, he is already much loved as a ‘writer’s writer’ among overseas readers and writers.

His works have sold over three million copies in the Czech Republic alone and have been translated and published in over 30 countries around the world, achieving great popularity.

"The Too Loud Solitude" is a short novel of only about 130 pages, but the weight of meaning it contains is by no means light.

Through the life of an old man named Hanty, Bohumil Hrabal offers profound insights into the human condition of constant labor, the changes in human life after the advent of machines that replace workers, and the anguish over humanity and existence.

And it is presented in a novel not just as a philosophical discourse, but as an interesting story about a living human being and as a sharp satire of the times.

“It ended up looking just like the books I’ve been compressing with my own hands!”

In the loneliness of a desperate and noisy world

A fiery monologue from an old dreamer who dreamed of existential liberation!

Czech national author Bohumil Hrabal's masterpiece, "Too Loud in Solitude," has been published by Munhakdongne.

Bohumil Hrabal is considered one of the most representative Czech writers, along with Milan Kundera, after Franz Kafka.

He is sometimes called the 'sad king of Czech novels' by foreign media and writers, because while many writers, including Milan Kundera, went into exile in France and other countries after the 'Prague Spring' and wrote in French, he remained in the Czech Republic and wrote in Czech until the end.

So, although his name is not widely known in Korea, he is already much loved as a ‘writer’s writer’ among overseas readers and writers.

His works have sold over three million copies in the Czech Republic alone and have been translated and published in over 30 countries around the world, achieving great popularity.

"The Too Loud Solitude" is a short novel of only about 130 pages, but the weight of meaning it contains is by no means light.

Through the life of an old man named Hanty, Bohumil Hrabal offers profound insights into the human condition of constant labor, the changes in human life after the advent of machines that replace workers, and the anguish over humanity and existence.

And it is presented in a novel not just as a philosophical discourse, but as an interesting story about a living human being and as a sharp satire of the times.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Translator's Note

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Translator's Note

Into the book

I know from books, from books, that heaven is not human.

It is also true that thinking humans are not human either.

It's not that I want to do that, but because the act of thinking itself conflicts with common sense.

Under my hands, inside my compressor, rare books are dying, but there is no stopping the flow.

I am just a gentle butcher.

Books taught me the joy and taste of destruction.

I love articles about pouring rain and buildings exploding.

I stand for hours watching the bombers blow away houses and streets like giant tires.

--- p.12

When I got home, I cleared away the hundred or so books that were blocking the kitchen door frame.

It was a door frame with my key marked in ink along with the date.

He placed his back against the doorpost, held a book against it to measure his height, then turned around and drew a line.

You could tell with the naked eye that I had lost 9 centimeters in eight years.

The moment I looked up at the canopy of books towering over the bed, I realized.

My body was bent over under the imaginary weight of the two-ton roof.

--- p.33

Back when we were still running around with axes and herding goats, the Gypsies had a nation somewhere in the world, a social structure that had already experienced two declines.

These Gypsies, who have lived in Prague for only two generations, like to light a ritual fire where they work.

It is a nomad's fire that burns only for joy.

It is a fire that blooms from roughly chopped firewood, a symbol of eternity that exists before all human thought, and also like the laughter of a child.

It is a free fire, a gift from heaven, a vivid symbol of elements that the disillusioned passerby can no longer perceive.

A fire born in the pits of the streets of Prague, burning logs to warm wandering eyes and souls.

--- pp.61~62

The moment the truth is revealed, a fear more terrible than pain overwhelms humanity.

All of this left me at a loss.

I suddenly felt proud and sacred that I had been able to see and experience all this with my whole body and mind in such a noisy solitude without going mad.

As I was doing this, I was amazed to realize that I had been thrown into the infinite realm of omnipotence.

--- p.75

She lay on top of me, looking into my face, tracing the line of my nose and lips with one finger, and occasionally kissing me.

We lay there, talking with our hands, staring at the burning sparks from the broken iron stove.

The fireplace looked like a cave with dying logs spewing out spiraling flames.

We had no other wish than to live like that forever.

It seemed like we had already come to an agreement on all this a long time ago.

It seemed like we had never left each other since we came into this world together.

It is also true that thinking humans are not human either.

It's not that I want to do that, but because the act of thinking itself conflicts with common sense.

Under my hands, inside my compressor, rare books are dying, but there is no stopping the flow.

I am just a gentle butcher.

Books taught me the joy and taste of destruction.

I love articles about pouring rain and buildings exploding.

I stand for hours watching the bombers blow away houses and streets like giant tires.

--- p.12

When I got home, I cleared away the hundred or so books that were blocking the kitchen door frame.

It was a door frame with my key marked in ink along with the date.

He placed his back against the doorpost, held a book against it to measure his height, then turned around and drew a line.

You could tell with the naked eye that I had lost 9 centimeters in eight years.

The moment I looked up at the canopy of books towering over the bed, I realized.

My body was bent over under the imaginary weight of the two-ton roof.

--- p.33

Back when we were still running around with axes and herding goats, the Gypsies had a nation somewhere in the world, a social structure that had already experienced two declines.

These Gypsies, who have lived in Prague for only two generations, like to light a ritual fire where they work.

It is a nomad's fire that burns only for joy.

It is a fire that blooms from roughly chopped firewood, a symbol of eternity that exists before all human thought, and also like the laughter of a child.

It is a free fire, a gift from heaven, a vivid symbol of elements that the disillusioned passerby can no longer perceive.

A fire born in the pits of the streets of Prague, burning logs to warm wandering eyes and souls.

--- pp.61~62

The moment the truth is revealed, a fear more terrible than pain overwhelms humanity.

All of this left me at a loss.

I suddenly felt proud and sacred that I had been able to see and experience all this with my whole body and mind in such a noisy solitude without going mad.

As I was doing this, I was amazed to realize that I had been thrown into the infinite realm of omnipotence.

--- p.75

She lay on top of me, looking into my face, tracing the line of my nose and lips with one finger, and occasionally kissing me.

We lay there, talking with our hands, staring at the burning sparks from the broken iron stove.

The fireplace looked like a cave with dying logs spewing out spiraling flames.

We had no other wish than to live like that forever.

It seemed like we had already come to an agreement on all this a long time ago.

It seemed like we had never left each other since we came into this world together.

--- p.81

Publisher's Review

A master of modern Czech literature, Bohumil Hrabal's life's work

Czech national author Bohumil Hrabal's masterpiece, "Too Loud in Solitude," has been published by Munhakdongne.

Bohumil Hrabal is considered one of the most representative Czech writers, along with Milan Kundera, after Franz Kafka.

He is sometimes called the 'sad king of Czech novels' by foreign media and writers, because while many writers, including Milan Kundera, went into exile in France and other countries after the 'Prague Spring' and wrote in French, he remained in the Czech Republic and wrote in Czech until the end.

So, although his name is not widely known in Korea, he is already much loved as a ‘writer’s writer’ among overseas readers and writers.

His works have sold over three million copies in the Czech Republic alone and have been translated and published in over 30 countries around the world, achieving great popularity.

Milan Kundera, a Czech writer himself, did not hide his admiration for Hrabal, calling him "the greatest Czech writer of our time." Julian Barnes referred to him as "the most sophisticated writer of our time." Philip Roth praised him, saying, "For me at least, he is the greatest novelist in modern Europe."

The literary review magazine [Tweeds Magazine] said, 'Hrabal is the Czech Proust.

No, it would be more correct to call Proust the Hrabal of France,' he wrote, lavishing his praise on him.

"The Loud Solitude" is a work that contains the essence of Hrabal, to the point that he himself declared, "I came into the world to write this work." It is a powerful novel that can be called the magnum opus of his life, and has received the love and attention of many readers and critics.

In 2014, the Czech Cultural Center in Korea held an exhibition titled “Too Loud Solitude” to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Bohumil Hrabal’s birth and introduced his world of work.

His works introduced in Korea so far include 『Serving the King of England』(Munhakdongne, 2009) and 『The Train Under Close Surveillance』(Vertigo, 2006).

The endless labor and agony of a man who locked himself in a basement

The novel's narrator, Han-Tya, is a person who has worked as a waste paper compactor for thirty-five years.

He operates a compressor with his bare hands in a dark, dirty basement, compressing the endless stream of waste paper that pours in.

There is a trapdoor in the ceiling, and from there, books filled with the knowledge and culture accumulated by mankind pour out every day.

Not only the brilliant literary works of Nietzsche, Goethe, Schiller, and Hölderlin, but also magazines containing drama reviews by Miroslav Ruthe and Karel Engelmüller.

Han-Tya's mission is to quickly shred and compress them, but he is drawn to the allure of piles of waste paper destined for destruction.

He reads and rereads the books that pour out and 'unintentionally' becomes cultured.

Han-Tya absorbs the knowledge contained in the waste paper like alcohol.

Living in a filthy environment infested with cockroaches and rats, and constantly being harassed and cursed by the owner, the repetitive labor is bearable when you think of the books pouring out.

As he collects valuable books separately, his apartment is filled with tons of books.

The books, piled precariously as if they might collapse at any moment, are the only pleasure that gives him a sense of happiness in his lonely life.

Even though he is now an old man, he still has women he used to be with.

Mancha, his childhood sweetheart who almost stayed with him for a long time, and a gypsy woman who happened to end up staying with him one day.

He recalls such memories and continues to work tirelessly, like the myth of Sisyphus.

The job is so tough that he has to drink several liters of beer every day, but he has been doing it for thirty-five years, and even when he retires, he dreams of buying a compressor and doing it until the day he dies.

I am alone only to live in solitude densely filled with thoughts.

In a way, I am Don Quixote, pursuing eternity and infinity.

People like me wouldn't have the ability to handle eternity and infinity.

(Pages 18-19)

The end of a world faced by a man who dreamed of eternity

While dealing with the weighty subject of the clash of two worlds, it never loses its wit and emotion.

His fiery monologues, written in a cynical yet humorous style, captivate the reader.

The story progresses between the present and the past.

The main story is Han-Tya's reflections through the boring and repetitive shredding work, but there are also interesting episodes interspersed here and there.

There are also many exciting elements, such as the endless battle between the rats divided into two camps, the slightly comical pity he feels for the cockroaches that keep jumping towards their deaths, and the witty descriptions of people approaching him to get the precious books.

And the episode with Mancha, the woman who shared his heart with him in the past, is humorous enough to make you burst out laughing.

Also, the episode with the gypsy woman who lived in the same space as him for a while seems dry, but it resonates emotionally and ultimately leaves a moving impression.

Each of the eight chapters begins with a sentence that is essentially the same, with only slight variations.

“For thirty-five years I have been working in a pile of waste paper.

(…) After thirty-five years of compressing books and waste paper, I have become very tired of the type, and I have come to resemble the encyclopedias that I must have compressed by hand, weighing at least three tons.” He has been doing this work since he was young and wants to continue doing it until the day he dies, but an event that will change his life occurs.

One day, while out in the city, he saw a huge compressor dozens of times larger than his own, and people wearing uniforms and drinking Coca-Cola in a new facility compressing waste paper.

They handle scrap paper with gloves on and during breaks they talk about their upcoming Greek vacation.

It becomes an event that can completely change Han-Tya's world.

After witnessing it, he realizes that his world is ending.

So, he doesn't even look at the books he loves and gets lost in the mad work of compacting waste paper.

Without even looking at the precious books that I had cherished so much, I began to work only for efficiency, like a city compression worker in uniform.

But he soon realizes.

That one's life, one's world, cannot be made that way.

I was so tense from the humiliation that I suddenly had a realization that sank deep into my bones.

I would never be able to adapt to my new life.

Like all those monks who committed suicide en masse when Copernicus discovered that the Earth was no longer the center of the universe.

They could not have imagined a world so different from the one that had sustained their lives until then.

(Page 106)

Deep insights into labor and human existence

A scathing satire on the times by a master of European literature

"The Too Loud Solitude" is a short novel of only about 130 pages, but the weight of meaning it contains is by no means light.

Through the life of an old man named Hanty, Bohumil Hrabal offers profound insights into the human condition of constant labor, the changes in human life after the advent of machines that replace workers, and the anguish over humanity and existence.

And it is presented in a novel not just as a philosophical discourse, but as an interesting story about a living human being and as a sharp satire of the times.

This novel, which also uses the myth of Sisyphus as a motif, raises sharp questions about what eternal labor and the true liberation of human intellect are.

Han-Tya finally announces the end of his world by walking into his own compressor.

This may seem like a simple symbol of the end of modernity, but it can also be read as a critique of the mad, directionless pursuit of development.

It can also be read as a political and philosophical allegory about a society that has become enslaved and dull, rather than regressing due to indiscriminate development.

The novel is more like a long meditation by an old dreamer who witnesses the end of a world.

Hrabal delicately portrays the mental state of a human being living in a harsh society where books are treated as mere scraps of paper.

His thinking, though sometimes seeming intoxicated and hallucinatory, remains consistently clear, making us think and dream about individuals rather than groups.

And above all, it reminds us of ‘things that are disappearing.’

The most beautiful and hopeful part of this novel is that Han-Tya never lets go of love and compassion.

The phrase "the sky is inhumane," which is constantly repeated like a chorus within the novel, is often varied as follows:

This is why, despite his tragic ending, we can find and feel a paradoxical warmth and breath of peace within him.

The sky is not human.

Yet, there is something beyond that sky, something of compassion and love.

Something I had forgotten for a long time, something that had been completely erased from my memory.

(Pages 85-86)

Press reviews

The greatest Czech writer of our time.

_Milan Kundera

At least to me, he is one of the greatest novelists in modern Europe.

_Philip Roth

Bohumil Hrabal is a most sophisticated novelist, with explosive humor and quiet, gentle detail.

We must read Hrabal.

_Julian Barnes

Hrabal's novel is perfectly paradoxical.

His writing, striking a brilliant balance between infinite desire and finite satisfaction, is both rational and profoundly rebellious, and constantly agonizing without losing wisdom.

James Wood (literary critic)

Bohumil Hrabal is the Czech Proust.

No, it would be more correct to say that Proust was the French Hrabal.

_Tweeds Magazine of Literature and Art

A fable that will keep the reader captivated.

_Publisher's Weekly

Czech national author Bohumil Hrabal's masterpiece, "Too Loud in Solitude," has been published by Munhakdongne.

Bohumil Hrabal is considered one of the most representative Czech writers, along with Milan Kundera, after Franz Kafka.

He is sometimes called the 'sad king of Czech novels' by foreign media and writers, because while many writers, including Milan Kundera, went into exile in France and other countries after the 'Prague Spring' and wrote in French, he remained in the Czech Republic and wrote in Czech until the end.

So, although his name is not widely known in Korea, he is already much loved as a ‘writer’s writer’ among overseas readers and writers.

His works have sold over three million copies in the Czech Republic alone and have been translated and published in over 30 countries around the world, achieving great popularity.

Milan Kundera, a Czech writer himself, did not hide his admiration for Hrabal, calling him "the greatest Czech writer of our time." Julian Barnes referred to him as "the most sophisticated writer of our time." Philip Roth praised him, saying, "For me at least, he is the greatest novelist in modern Europe."

The literary review magazine [Tweeds Magazine] said, 'Hrabal is the Czech Proust.

No, it would be more correct to call Proust the Hrabal of France,' he wrote, lavishing his praise on him.

"The Loud Solitude" is a work that contains the essence of Hrabal, to the point that he himself declared, "I came into the world to write this work." It is a powerful novel that can be called the magnum opus of his life, and has received the love and attention of many readers and critics.

In 2014, the Czech Cultural Center in Korea held an exhibition titled “Too Loud Solitude” to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Bohumil Hrabal’s birth and introduced his world of work.

His works introduced in Korea so far include 『Serving the King of England』(Munhakdongne, 2009) and 『The Train Under Close Surveillance』(Vertigo, 2006).

The endless labor and agony of a man who locked himself in a basement

The novel's narrator, Han-Tya, is a person who has worked as a waste paper compactor for thirty-five years.

He operates a compressor with his bare hands in a dark, dirty basement, compressing the endless stream of waste paper that pours in.

There is a trapdoor in the ceiling, and from there, books filled with the knowledge and culture accumulated by mankind pour out every day.

Not only the brilliant literary works of Nietzsche, Goethe, Schiller, and Hölderlin, but also magazines containing drama reviews by Miroslav Ruthe and Karel Engelmüller.

Han-Tya's mission is to quickly shred and compress them, but he is drawn to the allure of piles of waste paper destined for destruction.

He reads and rereads the books that pour out and 'unintentionally' becomes cultured.

Han-Tya absorbs the knowledge contained in the waste paper like alcohol.

Living in a filthy environment infested with cockroaches and rats, and constantly being harassed and cursed by the owner, the repetitive labor is bearable when you think of the books pouring out.

As he collects valuable books separately, his apartment is filled with tons of books.

The books, piled precariously as if they might collapse at any moment, are the only pleasure that gives him a sense of happiness in his lonely life.

Even though he is now an old man, he still has women he used to be with.

Mancha, his childhood sweetheart who almost stayed with him for a long time, and a gypsy woman who happened to end up staying with him one day.

He recalls such memories and continues to work tirelessly, like the myth of Sisyphus.

The job is so tough that he has to drink several liters of beer every day, but he has been doing it for thirty-five years, and even when he retires, he dreams of buying a compressor and doing it until the day he dies.

I am alone only to live in solitude densely filled with thoughts.

In a way, I am Don Quixote, pursuing eternity and infinity.

People like me wouldn't have the ability to handle eternity and infinity.

(Pages 18-19)

The end of a world faced by a man who dreamed of eternity

While dealing with the weighty subject of the clash of two worlds, it never loses its wit and emotion.

His fiery monologues, written in a cynical yet humorous style, captivate the reader.

The story progresses between the present and the past.

The main story is Han-Tya's reflections through the boring and repetitive shredding work, but there are also interesting episodes interspersed here and there.

There are also many exciting elements, such as the endless battle between the rats divided into two camps, the slightly comical pity he feels for the cockroaches that keep jumping towards their deaths, and the witty descriptions of people approaching him to get the precious books.

And the episode with Mancha, the woman who shared his heart with him in the past, is humorous enough to make you burst out laughing.

Also, the episode with the gypsy woman who lived in the same space as him for a while seems dry, but it resonates emotionally and ultimately leaves a moving impression.

Each of the eight chapters begins with a sentence that is essentially the same, with only slight variations.

“For thirty-five years I have been working in a pile of waste paper.

(…) After thirty-five years of compressing books and waste paper, I have become very tired of the type, and I have come to resemble the encyclopedias that I must have compressed by hand, weighing at least three tons.” He has been doing this work since he was young and wants to continue doing it until the day he dies, but an event that will change his life occurs.

One day, while out in the city, he saw a huge compressor dozens of times larger than his own, and people wearing uniforms and drinking Coca-Cola in a new facility compressing waste paper.

They handle scrap paper with gloves on and during breaks they talk about their upcoming Greek vacation.

It becomes an event that can completely change Han-Tya's world.

After witnessing it, he realizes that his world is ending.

So, he doesn't even look at the books he loves and gets lost in the mad work of compacting waste paper.

Without even looking at the precious books that I had cherished so much, I began to work only for efficiency, like a city compression worker in uniform.

But he soon realizes.

That one's life, one's world, cannot be made that way.

I was so tense from the humiliation that I suddenly had a realization that sank deep into my bones.

I would never be able to adapt to my new life.

Like all those monks who committed suicide en masse when Copernicus discovered that the Earth was no longer the center of the universe.

They could not have imagined a world so different from the one that had sustained their lives until then.

(Page 106)

Deep insights into labor and human existence

A scathing satire on the times by a master of European literature

"The Too Loud Solitude" is a short novel of only about 130 pages, but the weight of meaning it contains is by no means light.

Through the life of an old man named Hanty, Bohumil Hrabal offers profound insights into the human condition of constant labor, the changes in human life after the advent of machines that replace workers, and the anguish over humanity and existence.

And it is presented in a novel not just as a philosophical discourse, but as an interesting story about a living human being and as a sharp satire of the times.

This novel, which also uses the myth of Sisyphus as a motif, raises sharp questions about what eternal labor and the true liberation of human intellect are.

Han-Tya finally announces the end of his world by walking into his own compressor.

This may seem like a simple symbol of the end of modernity, but it can also be read as a critique of the mad, directionless pursuit of development.

It can also be read as a political and philosophical allegory about a society that has become enslaved and dull, rather than regressing due to indiscriminate development.

The novel is more like a long meditation by an old dreamer who witnesses the end of a world.

Hrabal delicately portrays the mental state of a human being living in a harsh society where books are treated as mere scraps of paper.

His thinking, though sometimes seeming intoxicated and hallucinatory, remains consistently clear, making us think and dream about individuals rather than groups.

And above all, it reminds us of ‘things that are disappearing.’

The most beautiful and hopeful part of this novel is that Han-Tya never lets go of love and compassion.

The phrase "the sky is inhumane," which is constantly repeated like a chorus within the novel, is often varied as follows:

This is why, despite his tragic ending, we can find and feel a paradoxical warmth and breath of peace within him.

The sky is not human.

Yet, there is something beyond that sky, something of compassion and love.

Something I had forgotten for a long time, something that had been completely erased from my memory.

(Pages 85-86)

Press reviews

The greatest Czech writer of our time.

_Milan Kundera

At least to me, he is one of the greatest novelists in modern Europe.

_Philip Roth

Bohumil Hrabal is a most sophisticated novelist, with explosive humor and quiet, gentle detail.

We must read Hrabal.

_Julian Barnes

Hrabal's novel is perfectly paradoxical.

His writing, striking a brilliant balance between infinite desire and finite satisfaction, is both rational and profoundly rebellious, and constantly agonizing without losing wisdom.

James Wood (literary critic)

Bohumil Hrabal is the Czech Proust.

No, it would be more correct to say that Proust was the French Hrabal.

_Tweeds Magazine of Literature and Art

A fable that will keep the reader captivated.

_Publisher's Weekly

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 8, 2016

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 144 pages | 238g | 128*188*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788954641548

- ISBN10: 8954641547

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)