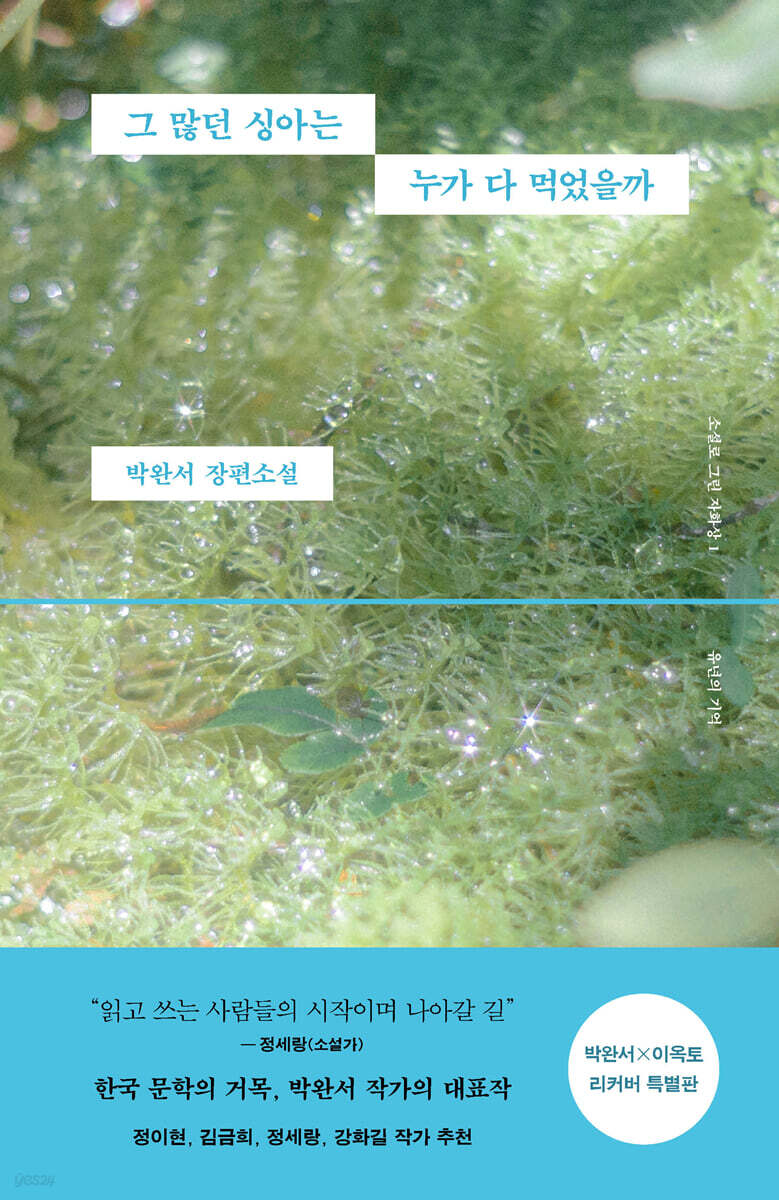

Who Ate All Those Singa? (Park Wan-seo X Lee Ok-to Recover Special Edition)

|

Description

Book Introduction

* Park Wan-seo × Lee Ok-to Recover Special Edition Published

* Recommended by authors Jeong I-hyeon, Kim Geum-hee, Jeong Se-rang, and Kang Hwa-gil

“The beginning and future path for those who read and write.”

-Jeong Se-rang (novelist)

A masterpiece by Park Wan-seo, a giant of Korean literature

I met new readers through the photos of author Lee Ok-to.

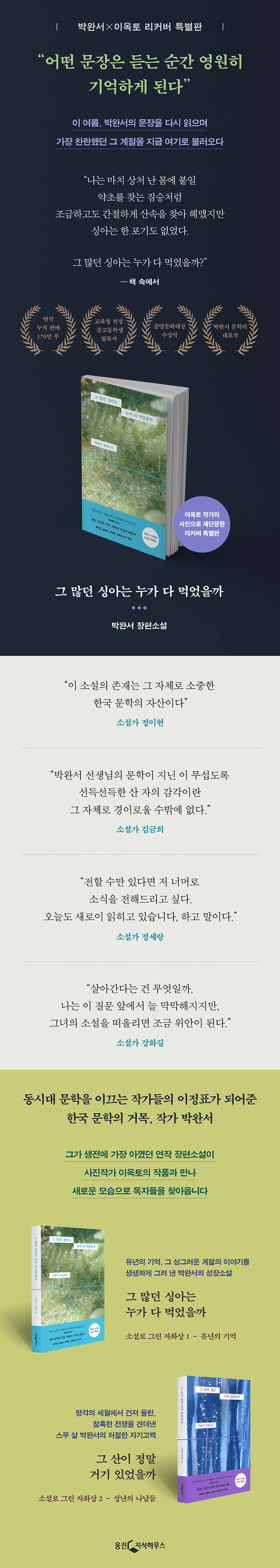

The representative works of Korean literary giant Park Wan-seo, the 'Self-Portrait in a Novel' series, 'Who Ate All the Singa?' and 'Was That Mountain Really There?' have been republished and are now available to readers in a special edition.

Even after more than 30 years since their publication, these two long novels have remained representative steady sellers of Korean novels and are beloved as required reading for middle and high school students, achieving the astonishing record of cumulative sales of over 1.7 million copies, leaving a lasting mark on the history of Korean literature as masterpieces.

The cover and binding are redesigned with the work of photographer Lee Ok-to, who heated up the '2025 Seoul International Book Fair,' bringing back that splendid and vivid space of memory.

"Who Ate All Those Singa?" is the first story in a series of autobiographical novels written by author Park Wan-seo, who has used her own experiences as material for her novels, "based purely on memory." It depicts her dreamlike childhood in the 1930s in Gaepung Parkjeokgol and her growing up years until she was twenty in Seoul, which was devastated by the Korean War in 1950.

* Recommended by authors Jeong I-hyeon, Kim Geum-hee, Jeong Se-rang, and Kang Hwa-gil

“The beginning and future path for those who read and write.”

-Jeong Se-rang (novelist)

A masterpiece by Park Wan-seo, a giant of Korean literature

I met new readers through the photos of author Lee Ok-to.

The representative works of Korean literary giant Park Wan-seo, the 'Self-Portrait in a Novel' series, 'Who Ate All the Singa?' and 'Was That Mountain Really There?' have been republished and are now available to readers in a special edition.

Even after more than 30 years since their publication, these two long novels have remained representative steady sellers of Korean novels and are beloved as required reading for middle and high school students, achieving the astonishing record of cumulative sales of over 1.7 million copies, leaving a lasting mark on the history of Korean literature as masterpieces.

The cover and binding are redesigned with the work of photographer Lee Ok-to, who heated up the '2025 Seoul International Book Fair,' bringing back that splendid and vivid space of memory.

"Who Ate All Those Singa?" is the first story in a series of autobiographical novels written by author Park Wan-seo, who has used her own experiences as material for her novels, "based purely on memory." It depicts her dreamlike childhood in the 1930s in Gaepung Parkjeokgol and her growing up years until she was twenty in Seoul, which was devastated by the Korean War in 1950.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Back to the beginning of the book

Author's Note

Wild season

Faraway Seoul

Outside the door

A child without friends

The house of the strange fire yard

Grandfather and Grandmother

My brother and mom

Spring in my hometown

A worn-out nameplate

Groping in the dark

The peace of the night before

A bright premonition

Commentary by Kim Yun-sik (Professor Emeritus, Seoul National University, Literary Critic)

Reading Park Wan-seo again now, Jeong I-hyeon (novelist)

Author's Note

Wild season

Faraway Seoul

Outside the door

A child without friends

The house of the strange fire yard

Grandfather and Grandmother

My brother and mom

Spring in my hometown

A worn-out nameplate

Groping in the dark

The peace of the night before

A bright premonition

Commentary by Kim Yun-sik (Professor Emeritus, Seoul National University, Literary Critic)

Reading Park Wan-seo again now, Jeong I-hyeon (novelist)

Detailed image

Into the book

But more than anything, the best thing about the back room was that it had a lot of nice poop.

We knew that excrement was not dirty, but returned to the ground and made cucumbers and pumpkins grow in abundance, and made watermelons and cantaloupes sweet.

So, I was able to experience not only the instinctive pleasure of excretion, but also the pride of producing something useful.

The back room was fun, but the beauty of the world when you come out of the back room after being there for too long is special.

The sunlight sparkling off the garden greens, the grass, the trees, and the stream was so dazzling and unfamiliar that we opened our eyes dimly and sighed.

I even felt like I was free from some forbidden pleasure.

Later, whenever I watched a movie that students were not allowed to see with the white collar of my uniform tucked in, and was exposed to the brightness and strangeness of the world, I felt as if the back room experience of my childhood was being repeated.

--- From "The Wild Period"

There were a lot of people sending messages outside the window.

Among them, the grandmother looked the smallest and most shabby.

The shabbiness seemed to pull me towards it.

How wonderful are glass windows.

I could clearly see tears welling up in my grandmother's eyes.

I wanted to cry along with my grandmother, feeling her caressing hand say, "Oh, my baby."

I clung to the glass window with my whole body.

I couldn't get even an inch closer to my grandmother, as if my face was pressed against the ice.

The train made a loud, mournful noise and then started moving.

The sender followed suit and gradually disappeared from view.

I didn't see whether my grandmother moved along or just stood there.

Tears flowed freely.

I've cried out loud many times without shedding tears, but this was the first time in my life that I cried so much without making a sound.

--- From "Far Away Seoul"

I did everything well, but what I hated the most was memorizing two addresses.

The first address my mother taught me was Sajik-dong, where the air conditioner was supposed to have been moved.

I memorized that in no time.

I wish that was the end of it, but I guess my mom suddenly thought it would be a big deal if I gave her that address when I got lost.

I trained him to memorize the address of his house in Hyeonjeong-dong.

It was a long one that ran all the way to the lake, but since I was at an age where I could memorize anything, it wasn't difficult, but my mother's worry was a bit excessive.

Perhaps it was out of naivety that I lied about my address when I submitted my application, but after memorizing both addresses so quickly, I started to worry that I would get them mixed up and say the wrong thing during the test.

Mom was just nagging me to make you feel safe.

If I were to sit still and then suddenly ask, “Where do you live? Where is your house? You’re lost.” Then I would have to give the address of Hyeonjeong-dong.

Conversely, if you asked, “Where do you live? You’re taking a test in front of the teacher right now,” you would have to give a fake address in Sajik-dong.

My mother was worried that I might confuse these two addresses.

(…) Mom regretted giving me two addresses for no reason, and told me to completely forget the Hyeonjeong-dong address until the exam date.

But just because you tell it to forget doesn't mean it will be forgotten.

The more my mother did that, the more that address became stuck in my head.

I've forgotten almost all the addresses of the many houses I've lived in since, including the address of Sajik-dong, but I still remember my first address: 418, 46 Hyeonjeong-dong.

--- From "Outside the Door"

Suddenly, I thought of Singa.

In our countryside, singa was as common a weed as dandelion.

It was anywhere, at the foot of the mountain or along the road.

The stem has nodes, and is at its most fleshy and tender around the time the thistle flowers bloom.

Breaking the reddish stem, peeling off the outer skin lengthwise, and eating the flesh was sweet and sour.

The sour taste that made my mouth water seemed like it would be just right for calming my upset stomach with the acacia flowers.

I searched the mountains impatiently and desperately, like an animal searching for herbs to apply to its wounded body, but there was not a single singa plant.

Who ate all those singa? I was retching until the sky turned blue, confusing that place with the hill behind my hometown.

--- From "The Child Without a Comrade"

It was also in the Goebul Madang house that World War II broke out.

The Japanese called it the Greater East Asia War.

I was excited without even knowing what it was.

We were already trained to be aggressive before that.

Japan was already waging a war called the Sino-Japanese War, and we were blatantly ignoring China, calling it "Chang-kola" and Chiang Kai-shek "Shogai-seki."

Even when fighting with my comrades, the worst insult was being teased by being called a "Jjangkola."

Every morning, when we would take the Imperial Subjects Oath during the morning assembly in the playground and then march to the classroom to the military march, my blood would run hot for no reason. It was a warlike passion, as if I had to defeat something and make a great leap forward.

--- From "The House in the Fire Yard"

But, strangely, no matter how much I shouted and asked this child and that child, it was no use, so my grandmother, who had learned it somewhere, started calling my name in Japanese this time.

It was just a tongue-tied, inarticulate babble that no one could understand, but I couldn't stand it any longer.

I shuddered with disgust at myself for making my grandmother pronounce those difficult words.

At times like that, crying was my only talent.

I shouted, “Grandma!” and ran towards her stiff skirt, starting to cry sadly.

My grandmother also kept patting my back, saying in a tearful voice, “Oh my baby, oh my baby.”

--- From "Grandfather and Grandmother"

When I returned home during the winter break of 1944, the situation in Bakjeokgol was also very dire.

When the police and the village clerk came out together to search for food, the whole village was turned upside down.

First of all, the devices they carried were more terrifying than the weapons.

He carried a sharp iron spear-like object at the end of a long pole and used it to stab things like the ceiling, the fireplace, the straw bales, and the fallen leaves.

It wasn't my village, but the rumor that a girl hiding in the leaves from a neighboring village had been stabbed in the side by that spearhead was so horrific that it was a broad daylight nightmare.

The reason the girl was hiding there was because of the comfort women.

Just a few days earlier, the girl's parents had heard a rumor that a Japanese policeman had taken a girl who was drawing water from a well in another village to a mental hospital. When the men in suits appeared outside the Donggu district, they were frightened and hid their daughter there.

Having people taken away was more frightening than having food taken away, and a world where people and food were taken away at the same time was clearly the end of the world.

--- From "Brother and Mother"

Was it because of all the ecstatic dreams one could have at the age of twenty that the road was so good? Was it because the trees, flowers, grass, and gentle breeze of the road made one's heart flutter so much? The road was filled with a fascination that could not be attributed to mere natural beauty.

Yes, what fascinated me that season was the anticipation of freedom.

Transitioning from middle school to college meant freedom from all kinds of taboos, but I had already prepared for freedom from my mother.

Maybe it would be different when I got married, but how could I have ever dreamed of being free from my mother when I was a girl?

No, it would be a lie to say that I never dreamed of it.

It was a dream within my dreams, my most intimate desire.

It was becoming a reality and was right before our eyes.

How to use that immense freedom—whether for good, bad, abuse, or moderation—was all fascinating.

From now on, everything will be in collusion with it.

That dream was more splendid than the May sunlight that makes roses, lilacs, and peonies bloom.

We knew that excrement was not dirty, but returned to the ground and made cucumbers and pumpkins grow in abundance, and made watermelons and cantaloupes sweet.

So, I was able to experience not only the instinctive pleasure of excretion, but also the pride of producing something useful.

The back room was fun, but the beauty of the world when you come out of the back room after being there for too long is special.

The sunlight sparkling off the garden greens, the grass, the trees, and the stream was so dazzling and unfamiliar that we opened our eyes dimly and sighed.

I even felt like I was free from some forbidden pleasure.

Later, whenever I watched a movie that students were not allowed to see with the white collar of my uniform tucked in, and was exposed to the brightness and strangeness of the world, I felt as if the back room experience of my childhood was being repeated.

--- From "The Wild Period"

There were a lot of people sending messages outside the window.

Among them, the grandmother looked the smallest and most shabby.

The shabbiness seemed to pull me towards it.

How wonderful are glass windows.

I could clearly see tears welling up in my grandmother's eyes.

I wanted to cry along with my grandmother, feeling her caressing hand say, "Oh, my baby."

I clung to the glass window with my whole body.

I couldn't get even an inch closer to my grandmother, as if my face was pressed against the ice.

The train made a loud, mournful noise and then started moving.

The sender followed suit and gradually disappeared from view.

I didn't see whether my grandmother moved along or just stood there.

Tears flowed freely.

I've cried out loud many times without shedding tears, but this was the first time in my life that I cried so much without making a sound.

--- From "Far Away Seoul"

I did everything well, but what I hated the most was memorizing two addresses.

The first address my mother taught me was Sajik-dong, where the air conditioner was supposed to have been moved.

I memorized that in no time.

I wish that was the end of it, but I guess my mom suddenly thought it would be a big deal if I gave her that address when I got lost.

I trained him to memorize the address of his house in Hyeonjeong-dong.

It was a long one that ran all the way to the lake, but since I was at an age where I could memorize anything, it wasn't difficult, but my mother's worry was a bit excessive.

Perhaps it was out of naivety that I lied about my address when I submitted my application, but after memorizing both addresses so quickly, I started to worry that I would get them mixed up and say the wrong thing during the test.

Mom was just nagging me to make you feel safe.

If I were to sit still and then suddenly ask, “Where do you live? Where is your house? You’re lost.” Then I would have to give the address of Hyeonjeong-dong.

Conversely, if you asked, “Where do you live? You’re taking a test in front of the teacher right now,” you would have to give a fake address in Sajik-dong.

My mother was worried that I might confuse these two addresses.

(…) Mom regretted giving me two addresses for no reason, and told me to completely forget the Hyeonjeong-dong address until the exam date.

But just because you tell it to forget doesn't mean it will be forgotten.

The more my mother did that, the more that address became stuck in my head.

I've forgotten almost all the addresses of the many houses I've lived in since, including the address of Sajik-dong, but I still remember my first address: 418, 46 Hyeonjeong-dong.

--- From "Outside the Door"

Suddenly, I thought of Singa.

In our countryside, singa was as common a weed as dandelion.

It was anywhere, at the foot of the mountain or along the road.

The stem has nodes, and is at its most fleshy and tender around the time the thistle flowers bloom.

Breaking the reddish stem, peeling off the outer skin lengthwise, and eating the flesh was sweet and sour.

The sour taste that made my mouth water seemed like it would be just right for calming my upset stomach with the acacia flowers.

I searched the mountains impatiently and desperately, like an animal searching for herbs to apply to its wounded body, but there was not a single singa plant.

Who ate all those singa? I was retching until the sky turned blue, confusing that place with the hill behind my hometown.

--- From "The Child Without a Comrade"

It was also in the Goebul Madang house that World War II broke out.

The Japanese called it the Greater East Asia War.

I was excited without even knowing what it was.

We were already trained to be aggressive before that.

Japan was already waging a war called the Sino-Japanese War, and we were blatantly ignoring China, calling it "Chang-kola" and Chiang Kai-shek "Shogai-seki."

Even when fighting with my comrades, the worst insult was being teased by being called a "Jjangkola."

Every morning, when we would take the Imperial Subjects Oath during the morning assembly in the playground and then march to the classroom to the military march, my blood would run hot for no reason. It was a warlike passion, as if I had to defeat something and make a great leap forward.

--- From "The House in the Fire Yard"

But, strangely, no matter how much I shouted and asked this child and that child, it was no use, so my grandmother, who had learned it somewhere, started calling my name in Japanese this time.

It was just a tongue-tied, inarticulate babble that no one could understand, but I couldn't stand it any longer.

I shuddered with disgust at myself for making my grandmother pronounce those difficult words.

At times like that, crying was my only talent.

I shouted, “Grandma!” and ran towards her stiff skirt, starting to cry sadly.

My grandmother also kept patting my back, saying in a tearful voice, “Oh my baby, oh my baby.”

--- From "Grandfather and Grandmother"

When I returned home during the winter break of 1944, the situation in Bakjeokgol was also very dire.

When the police and the village clerk came out together to search for food, the whole village was turned upside down.

First of all, the devices they carried were more terrifying than the weapons.

He carried a sharp iron spear-like object at the end of a long pole and used it to stab things like the ceiling, the fireplace, the straw bales, and the fallen leaves.

It wasn't my village, but the rumor that a girl hiding in the leaves from a neighboring village had been stabbed in the side by that spearhead was so horrific that it was a broad daylight nightmare.

The reason the girl was hiding there was because of the comfort women.

Just a few days earlier, the girl's parents had heard a rumor that a Japanese policeman had taken a girl who was drawing water from a well in another village to a mental hospital. When the men in suits appeared outside the Donggu district, they were frightened and hid their daughter there.

Having people taken away was more frightening than having food taken away, and a world where people and food were taken away at the same time was clearly the end of the world.

--- From "Brother and Mother"

Was it because of all the ecstatic dreams one could have at the age of twenty that the road was so good? Was it because the trees, flowers, grass, and gentle breeze of the road made one's heart flutter so much? The road was filled with a fascination that could not be attributed to mere natural beauty.

Yes, what fascinated me that season was the anticipation of freedom.

Transitioning from middle school to college meant freedom from all kinds of taboos, but I had already prepared for freedom from my mother.

Maybe it would be different when I got married, but how could I have ever dreamed of being free from my mother when I was a girl?

No, it would be a lie to say that I never dreamed of it.

It was a dream within my dreams, my most intimate desire.

It was becoming a reality and was right before our eyes.

How to use that immense freedom—whether for good, bad, abuse, or moderation—was all fascinating.

From now on, everything will be in collusion with it.

That dream was more splendid than the May sunlight that makes roses, lilacs, and peonies bloom.

---From "A Brilliant Premonition"

Publisher's Review

“It’s great that there is a next generation that will accept the space of my vivid memories.

“It can’t be anything but a privilege to be a writer.”

A collaboration between Park Wan-seo's masterpiece, beloved by 1.7 million people, and photographer Lee Ok-to.

Reviving the Great Tree's Sentence Here and Now

Author Park Wan-seo's novel series, "Self-Portrait in a Novel," is now reborn with a new cover and is now available to readers here.

“Who Ate All Those Singa?” (1992) and “Was That Mountain Really There?” (1995) are autobiographical novels written by the author, who passed away in 2011 at the age of 80, based on his own experiences.

This series has sold over 1.7 million copies since its publication over 30 years ago, and is a representative steady seller among Korean novels and a must-read for middle and high school students.

Among these, at the 14th anniversary memorial reading performance of author Park Wan-seo, hosted by Guri City in March 2025, 『Those Many Singas…』 was read in Park Wan-seo’s voice recreated using AI technology, which became a hot topic.

And in August 2025, two of Park Wan-seo's representative literary works met with the work of photographer Lee Ok-to and were reborn as the 'Park Wan-seo x Lee Ok-to Recover Special Edition.'

Author Lee Ok-to is the photographer who worked on the cover photo of the reissued edition of 『The Vegetarian』 (Han Kang). He became a hot topic among readers in their 20s and 30s as he created an 'open run' scene at the '2025 Seoul International Book Fair' with readers trying to purchase the 'transparent bookmarks' he produced.

On the cover of the special edition of Park Wan-seo's Recover, author Lee Ok-to has depicted the story of that season in the novel, which cannot be returned to but lives and breathes forever in our memories, with the fresh and transparent image of summer.

The water-blue meadow scenery on the cover of 『Those Many Singas…』 evokes brilliant memories of my childhood in Bakjeokgol, and the cold car window scene on the cover of 『That Mountain Really…』 evokes the strong hope and humanity that bloom like frost flowers in the storm of history.

That sentence you will remember forever the moment you hear it,

“Where did all those singas go?”

Memories of Childhood: A Vivid Story of the Season That Inspired Park Wan-seo's World

Author Park Wan-seo, who has used her own experiences as material for her novels, wrote the first story of her "Self-Portrait Drawn through Novels" "Relying purely on memory," "Who Ate All Those Singa?" depicts her dreamlike childhood in the 1930s in Gaepung Parkjeokgol and her twenties in Seoul, devastated by the Korean War in 1950.

The first half of the novel shows Park Wan-seo's unique wit in the customs of the Gaepung region in the 1930s, the unspoiled mountains and rivers, and the innocent play of children of that time who sought all their entertainment in nature.

The charm of the writing style that freely uses pure Korean with rich sensibility can be felt throughout the novel, and in particular, there is a passage that gives a glimpse of the fact that it was here, in Parkjeokgol, that Park Wan-seo's unique sensibility, which extracts exquisite sorrow and beauty even from seemingly trivial scenes, began to develop.

I couldn't stand it anymore so I burst into tears.

My mother didn't understand my sudden crying.

I couldn't explain it either.

It was pure sorrow.

There were similar experiences after that.

What can compare to the sorrow I feel when I return home alone, having parted ways with my companions on an evening when the wind feels particularly dreary, and look at the sorghum heads swaying in the wind at the edge of the garden against the backdrop of the ridge with its persimmon-colored afterglow?

(Pages 32-33)

The author's innocent childhood, represented by the common grass 'Singa' that grew in abundance in the mountains and rivers of his hometown, evokes a more and more faint longing as the story unfolds.

“It depicts a time when something was once common but now has no trace, a time that can only be restored through groping memories” (Jeong I-Hyeon), and it makes readers sigh, thinking, “Where did all those ○○s go?”

This novel, which was selected for MBC's [Exclamation Mark] 'Let's Read Books' and became a bestseller, sparked a nationwide 'Singa' craze and became a national novel.

“I had a feeling that I would write about it someday in the future.

“That premonition drove out the fear.”

Digging through the pile of memories, I completed it in a watercolor painting.

The essence of a sharp, shining coming-of-age novel

If 'Singa' represents the refreshing childhood of the protagonist 'Na', the poverty-stricken life in Seoul that unfolds from the middle part of the novel, where one's nose is cut off even with one's eyes open, and the 'acacia' that covers the foot of Inwangsan Mountain are metaphors for the painful rite of passage for his growth.

The film depicts 'I' gradually coming to understand the world through the sad life of a student in Seoul in the 1940s under Japanese colonial rule, where he had to be mindful of his master's opinion even when going to the bathroom.

I searched the mountains impatiently and desperately, like an animal searching for herbs to apply to its wounded body, but there was not a single singa plant.

Who ate all those singa? I was retching until the sky turned blue, confusing that place with the hill behind my hometown.

(Page 89)

As the novel enters its latter half, the world surrounding 'I' is now caught up in the turbulent waves of Korean history in 1950 and is on the verge of being shattered into a state of crisis.

The novel ends with the author feeling a premonition that he will one day write about the family unity that was brutally shattered by war and the unfortunate coincidences that led to it, and it is like a prequel that foreshadows the emergence of Park Wan-seo, a giant of modern Korean literature.

"The very existence of this novel is a valuable asset to Korean literature" (Jeong I-hyeon)

The one who proves memory through novels, Park Wan-seo’s literary world

A work that perfectly reproduces the beginning, middle, and end

『Those Many Singas…』 perfectly reproduces the beginning, middle, and end of the autobiographical elements that have been revealed in fragments or novelistically transformed in Park Wan-seo’s many novels that have already been published.

In particular, the author's family relationships, which have been the subject of constant novelistic exploration in many works, including "Mother's Stake 2," the winner of the 5th Yi Sang Literary Award, are sharply depicted and drive the story within the work.

The late Professor Kim Yun-sik, who wrote the commentary on the novel 『Those Many Singas…』, mentioned this point and explained why this novel is the origin or prototype of Park Wan-seo’s literature.

If you are a reader who has been reading this author's previous works attentively, you will be able to recognize that this work, "Those Many Singas...", which relies "purely" on "memory" and is "Mother's Stake 4," which this author has been writing carefully.

If "Mother's Stake 1" is about the struggles of Mrs. Gi-suk, who came to Seoul from Bakjeokgol and stayed in Hyeonjeong-dong selling sewing supplies, then "Mother's Stake 2" is the story that follows, and "Mother's Stake 3" deals with Mrs. Gi-suk's death.

(…) Author Park never left behind a work with the number (4).

I would like to dedicate the number (4) to it.

- Kim Yun-sik, from “Commentary on the Work”

The author said before his death, “The root of my literature is my mother.”

As the novel progresses, 'I' and my family are thrown into a world without even my uncle and older brother, who were like fathers to me.

The novel ends with the strong mother, the clever and resilient Olke, and 'I', who vows to remember and testify to all these scenes, left behind in the empty Seoul immediately after the Korean War, and the baton of the story is passed on to the sequel, 'Was That Mountain Really There?'

『Those Many Singas…』 depicts the intimate family history of author Park Wan-seo, including her older brother who joined the left wing out of naive idealism and was eventually dragged into the volunteer army and returned half-dead; her own brother who was accused of being a communist by the townspeople and subjected to all kinds of interrogation; and her uncle who was sentenced to death on charges of collaborating with the People's Army. However, it also serves as a testimonial literature that shows in greater detail than any other source material the major events in modern Korean history from the Japanese colonial period to before and after liberation.

This novel is a dazzling coming-of-age novel that explores the meaning of life through the growth of an individual, while also vividly exposing the dark side of Korean society. It can be said to be Park Wan-seo's masterpiece.

“It can’t be anything but a privilege to be a writer.”

A collaboration between Park Wan-seo's masterpiece, beloved by 1.7 million people, and photographer Lee Ok-to.

Reviving the Great Tree's Sentence Here and Now

Author Park Wan-seo's novel series, "Self-Portrait in a Novel," is now reborn with a new cover and is now available to readers here.

“Who Ate All Those Singa?” (1992) and “Was That Mountain Really There?” (1995) are autobiographical novels written by the author, who passed away in 2011 at the age of 80, based on his own experiences.

This series has sold over 1.7 million copies since its publication over 30 years ago, and is a representative steady seller among Korean novels and a must-read for middle and high school students.

Among these, at the 14th anniversary memorial reading performance of author Park Wan-seo, hosted by Guri City in March 2025, 『Those Many Singas…』 was read in Park Wan-seo’s voice recreated using AI technology, which became a hot topic.

And in August 2025, two of Park Wan-seo's representative literary works met with the work of photographer Lee Ok-to and were reborn as the 'Park Wan-seo x Lee Ok-to Recover Special Edition.'

Author Lee Ok-to is the photographer who worked on the cover photo of the reissued edition of 『The Vegetarian』 (Han Kang). He became a hot topic among readers in their 20s and 30s as he created an 'open run' scene at the '2025 Seoul International Book Fair' with readers trying to purchase the 'transparent bookmarks' he produced.

On the cover of the special edition of Park Wan-seo's Recover, author Lee Ok-to has depicted the story of that season in the novel, which cannot be returned to but lives and breathes forever in our memories, with the fresh and transparent image of summer.

The water-blue meadow scenery on the cover of 『Those Many Singas…』 evokes brilliant memories of my childhood in Bakjeokgol, and the cold car window scene on the cover of 『That Mountain Really…』 evokes the strong hope and humanity that bloom like frost flowers in the storm of history.

That sentence you will remember forever the moment you hear it,

“Where did all those singas go?”

Memories of Childhood: A Vivid Story of the Season That Inspired Park Wan-seo's World

Author Park Wan-seo, who has used her own experiences as material for her novels, wrote the first story of her "Self-Portrait Drawn through Novels" "Relying purely on memory," "Who Ate All Those Singa?" depicts her dreamlike childhood in the 1930s in Gaepung Parkjeokgol and her twenties in Seoul, devastated by the Korean War in 1950.

The first half of the novel shows Park Wan-seo's unique wit in the customs of the Gaepung region in the 1930s, the unspoiled mountains and rivers, and the innocent play of children of that time who sought all their entertainment in nature.

The charm of the writing style that freely uses pure Korean with rich sensibility can be felt throughout the novel, and in particular, there is a passage that gives a glimpse of the fact that it was here, in Parkjeokgol, that Park Wan-seo's unique sensibility, which extracts exquisite sorrow and beauty even from seemingly trivial scenes, began to develop.

I couldn't stand it anymore so I burst into tears.

My mother didn't understand my sudden crying.

I couldn't explain it either.

It was pure sorrow.

There were similar experiences after that.

What can compare to the sorrow I feel when I return home alone, having parted ways with my companions on an evening when the wind feels particularly dreary, and look at the sorghum heads swaying in the wind at the edge of the garden against the backdrop of the ridge with its persimmon-colored afterglow?

(Pages 32-33)

The author's innocent childhood, represented by the common grass 'Singa' that grew in abundance in the mountains and rivers of his hometown, evokes a more and more faint longing as the story unfolds.

“It depicts a time when something was once common but now has no trace, a time that can only be restored through groping memories” (Jeong I-Hyeon), and it makes readers sigh, thinking, “Where did all those ○○s go?”

This novel, which was selected for MBC's [Exclamation Mark] 'Let's Read Books' and became a bestseller, sparked a nationwide 'Singa' craze and became a national novel.

“I had a feeling that I would write about it someday in the future.

“That premonition drove out the fear.”

Digging through the pile of memories, I completed it in a watercolor painting.

The essence of a sharp, shining coming-of-age novel

If 'Singa' represents the refreshing childhood of the protagonist 'Na', the poverty-stricken life in Seoul that unfolds from the middle part of the novel, where one's nose is cut off even with one's eyes open, and the 'acacia' that covers the foot of Inwangsan Mountain are metaphors for the painful rite of passage for his growth.

The film depicts 'I' gradually coming to understand the world through the sad life of a student in Seoul in the 1940s under Japanese colonial rule, where he had to be mindful of his master's opinion even when going to the bathroom.

I searched the mountains impatiently and desperately, like an animal searching for herbs to apply to its wounded body, but there was not a single singa plant.

Who ate all those singa? I was retching until the sky turned blue, confusing that place with the hill behind my hometown.

(Page 89)

As the novel enters its latter half, the world surrounding 'I' is now caught up in the turbulent waves of Korean history in 1950 and is on the verge of being shattered into a state of crisis.

The novel ends with the author feeling a premonition that he will one day write about the family unity that was brutally shattered by war and the unfortunate coincidences that led to it, and it is like a prequel that foreshadows the emergence of Park Wan-seo, a giant of modern Korean literature.

"The very existence of this novel is a valuable asset to Korean literature" (Jeong I-hyeon)

The one who proves memory through novels, Park Wan-seo’s literary world

A work that perfectly reproduces the beginning, middle, and end

『Those Many Singas…』 perfectly reproduces the beginning, middle, and end of the autobiographical elements that have been revealed in fragments or novelistically transformed in Park Wan-seo’s many novels that have already been published.

In particular, the author's family relationships, which have been the subject of constant novelistic exploration in many works, including "Mother's Stake 2," the winner of the 5th Yi Sang Literary Award, are sharply depicted and drive the story within the work.

The late Professor Kim Yun-sik, who wrote the commentary on the novel 『Those Many Singas…』, mentioned this point and explained why this novel is the origin or prototype of Park Wan-seo’s literature.

If you are a reader who has been reading this author's previous works attentively, you will be able to recognize that this work, "Those Many Singas...", which relies "purely" on "memory" and is "Mother's Stake 4," which this author has been writing carefully.

If "Mother's Stake 1" is about the struggles of Mrs. Gi-suk, who came to Seoul from Bakjeokgol and stayed in Hyeonjeong-dong selling sewing supplies, then "Mother's Stake 2" is the story that follows, and "Mother's Stake 3" deals with Mrs. Gi-suk's death.

(…) Author Park never left behind a work with the number (4).

I would like to dedicate the number (4) to it.

- Kim Yun-sik, from “Commentary on the Work”

The author said before his death, “The root of my literature is my mother.”

As the novel progresses, 'I' and my family are thrown into a world without even my uncle and older brother, who were like fathers to me.

The novel ends with the strong mother, the clever and resilient Olke, and 'I', who vows to remember and testify to all these scenes, left behind in the empty Seoul immediately after the Korean War, and the baton of the story is passed on to the sequel, 'Was That Mountain Really There?'

『Those Many Singas…』 depicts the intimate family history of author Park Wan-seo, including her older brother who joined the left wing out of naive idealism and was eventually dragged into the volunteer army and returned half-dead; her own brother who was accused of being a communist by the townspeople and subjected to all kinds of interrogation; and her uncle who was sentenced to death on charges of collaborating with the People's Army. However, it also serves as a testimonial literature that shows in greater detail than any other source material the major events in modern Korean history from the Japanese colonial period to before and after liberation.

This novel is a dazzling coming-of-age novel that explores the meaning of life through the growth of an individual, while also vividly exposing the dark side of Korean society. It can be said to be Park Wan-seo's masterpiece.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 18, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 356 pages | 414g | 130*200*21mm

- ISBN13: 9788901296906

- ISBN10: 890129690X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)