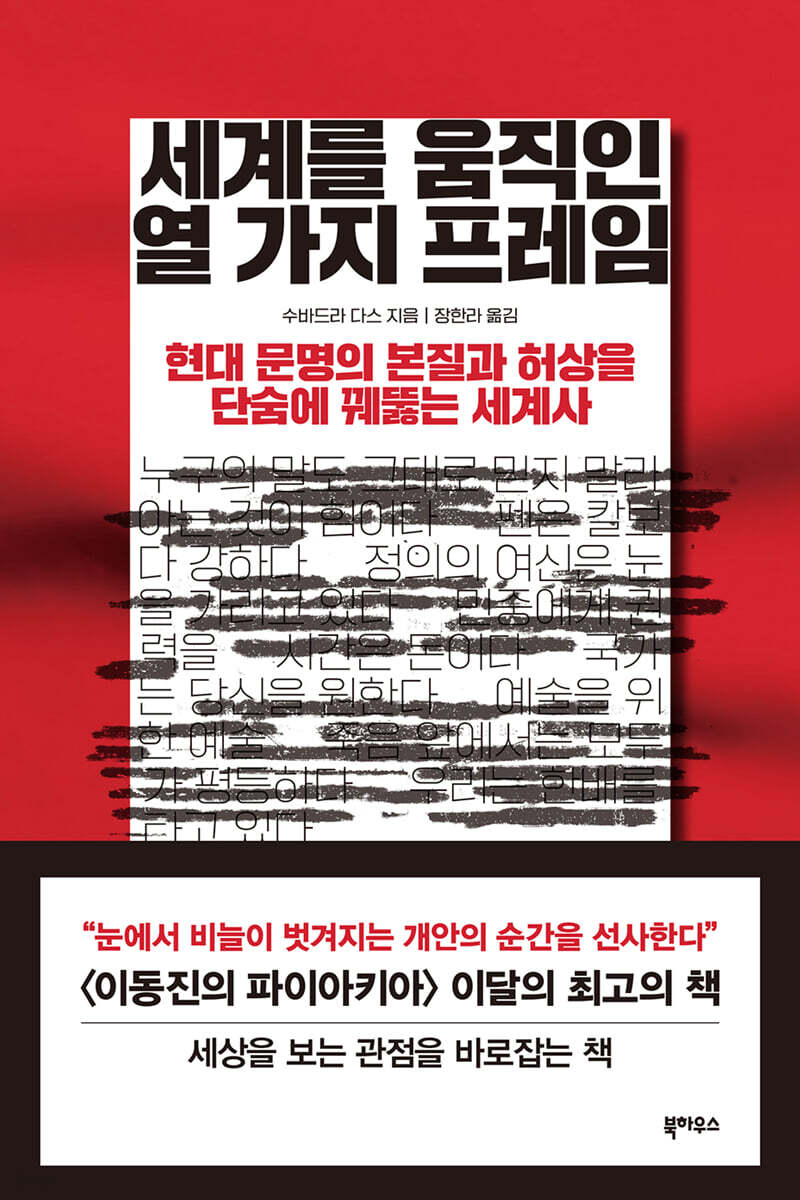

Ten Frames That Moved the World

|

Description

Book Introduction

“My life motto is a frame that obscures the truth of the world!”

'Never take anyone's word for it', 'Knowledge is power', 'Time is money'.

“The pen is mightier than the sword”… These words, which everyone has likely heard, are accepted as unquestionable wisdom in our society.

"Ten Frames That Moved the World" examines the hidden side of ten core values, shared as achievements of modern civilization and long-held beliefs, and explores their impact on history and our thinking.

Science is the pinnacle of value-neutral reason, education is the center of the liberal arts that makes us human, time is a resource that can be efficiently utilized to create value, and writing is a magical tool capable of expressing all thoughts and events… These are our universal beliefs, and we consider possessing them the foundation of civilization.

A society or people who do not naturally have this are considered barbaric and uncivilized.

The question begins here.

Where do concepts like "science," "education," "writing," and "time," so deeply ingrained in our minds, originate? Where do the standards of civilization we have established come from? Who established them, and crucially, who benefits from them? This book explores the genesis of ten core concepts that underpin modern civilization, examining how Western powers have used these frameworks to divide the world into civilization and barbarism, and to unfold a history of oppression and exploitation.

'Never take anyone's word for it', 'Knowledge is power', 'Time is money'.

“The pen is mightier than the sword”… These words, which everyone has likely heard, are accepted as unquestionable wisdom in our society.

"Ten Frames That Moved the World" examines the hidden side of ten core values, shared as achievements of modern civilization and long-held beliefs, and explores their impact on history and our thinking.

Science is the pinnacle of value-neutral reason, education is the center of the liberal arts that makes us human, time is a resource that can be efficiently utilized to create value, and writing is a magical tool capable of expressing all thoughts and events… These are our universal beliefs, and we consider possessing them the foundation of civilization.

A society or people who do not naturally have this are considered barbaric and uncivilized.

The question begins here.

Where do concepts like "science," "education," "writing," and "time," so deeply ingrained in our minds, originate? Where do the standards of civilization we have established come from? Who established them, and crucially, who benefits from them? This book explores the genesis of ten core concepts that underpin modern civilization, examining how Western powers have used these frameworks to divide the world into civilization and barbarism, and to unfold a history of oppression and exploitation.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction

1.

Don't Take Anyone's Words: Science

Nullius in verba

2.

Knowledge is Power: Education

Knowledge is power

3.

The pen is mightier than the sword: letters

The pen is mightier than the sword

4.

The Goddess of Justice is blindfolded: the law

Justice is blind

5.

Power to the People: Democracy

Power to the people

6.

Time is money: time

Time is money

7.

The country wants you: the citizen

Your country needs you

8.

Art for Art's Sake: Art

Art for art's sake

9.

All are equal before death: death

Death is the great equalizer

10.

We're in the same boat: the common good

We're all in this together

Words that come out

Acknowledgements

References

1.

Don't Take Anyone's Words: Science

Nullius in verba

2.

Knowledge is Power: Education

Knowledge is power

3.

The pen is mightier than the sword: letters

The pen is mightier than the sword

4.

The Goddess of Justice is blindfolded: the law

Justice is blind

5.

Power to the People: Democracy

Power to the people

6.

Time is money: time

Time is money

7.

The country wants you: the citizen

Your country needs you

8.

Art for Art's Sake: Art

Art for art's sake

9.

All are equal before death: death

Death is the great equalizer

10.

We're in the same boat: the common good

We're all in this together

Words that come out

Acknowledgements

References

Detailed image

Into the book

As Western civilization gained significance, the practices and values we associate with it today—democracy, justice, and the rationality of science, to name just a few—emerged in step with the growing ambitions and power of European empires.

It was the colonial rulers who decided what and where was civilized, and they defined civilization within their own framework.

They claim that they are not only more powerful, but also more socially, culturally, and intellectually advanced than the rest of the world.

(…) Western civilization is, in many ways (at least in ten aspects, as we will see), a case of successful branding that suppresses reality.

A look into the history of the West reveals that Western civilization is not simply a product, but a process.

The 'mission of civilization' was the vision and justification of the nations that established colonies.

The European powers did not simply appropriate the rest of the world; they completely reshaped it within the framework of the civilization they had created.

(…) Rather than simply exposing the lies behind these notions, I want to try to understand how we were so easily fooled into believing these notions were true in the first place.

We will learn what the words we use without much thought actually mean and what claims are implied in those terms.

--- p.14~17, from “Introductory Remarks”

Frazer's work solidified established ideas about cultural development, progress, and civilization.

Needless to say, early versions of this idea were closely tied to the scientific concept of race.

As with taxonomy and the classification of life on Earth, observations of physical appearance continue to be closely linked to more abstract qualities such as intelligence and behavior.

James Cowles-Pritchard, the most important British folklorist of the 19th century, believed that the white skin and greater intelligence of Europeans were the direct result of a civilizing process that darker-skinned peoples had not yet undergone.

Henri de Saint-Simon had a less positive view of the possibility of civilization change.

He justified France's reinstitution of slavery by saying that black Africans could not attain the same high intelligence as white Europeans.

Anthropologist Frederick Farrar also agreed.

In his 1866 lecture, "Aptitude of Races," Farrar divided the world's people into three groups.

There were barbarian groups, semi-civilized groups, and civilized groups.

He described those he considered savages as having “no past or future,” “no redemption,” and being frozen in time like “living fossils,” beyond anything that could be done about them.

(…) Science has become a frame for understanding the world, and within it, we humans have become a subject of discussion.

And so, a place was created for civilized people who claimed to be worthy of continuing to ask discussion questions.

(…) The result of the powerful combination of science, race, and civilization was that non-Westerners were, from a scientific perspective, rotten to the core, even when they might simply be 'read' as behaving incomprehensibly or incomprehensibly.

As a result, the answer to the question of humanity can now only be proven in one specific way.

Only through the methods of science itself.

When people from non-Western regions, especially those who are not considered racially white, say that they are human, we are unlikely to take that at face value.

It is not our responsibility to believe them, but their responsibility to prove that this is true.

Race is not a subject of debate, and by extension, arguing with racists is virtually pointless.

Racists would have you believe that race really exists, and science is their alibi.

Science allows racists to keep a safe distance.

The saying, "Never take anyone's word for it" may seem obvious, but let's look a little closer at the broader historical context.

It then becomes clear that the foundations of science, and particularly the foundations of racial science, serve a deeper purpose.

Being white and being civilized simultaneously means being powerful.

--- p.45~48, from Chapter 1, “Don’t Take Anyone’s Words at Face”

It is known that in England the term 'classics' first came to mean the study of ancient authors by wealthy young people around 1684.

This was because a group calling themselves “some young men educated at Hatton Garden” published their own translation of the work of Eutropius, a 4th-century official who wrote the history of the founding of Rome.

This was a time when London was rising from the ashes of the Great Fire of 1666 like a phoenix, bearing the spirit of empire, and the idea that, as Francis Bacon put it, "knowledge is power" was firmly established.

Louise Madewell, a teacher at Hatton Garden, wrote in the book's preface that if the British were more serious about education, "the sleeping talents of England would awaken of their own accord."

Education was not simply a matter of expanding the mental world.

Education was also a key tool in broadening the horizons of the British Empire and solidifying its power.

(…)

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a series of leaked documents exposed the inferior counterfeiting within the British education system.

One of these is the report 'Harringay Comprehensive Secondary School' (1969), commonly known as the Dalton Report after its author.

The report sparked disappointment and anger in black communities in north London.

Schools with a large number of West Indian students were said to have to lower their standards.

This was because these children were generally thought to have much lower IQs than white British students.

And a follow-up report, the 'Report of the Education Committee on Integrated Education', recommended that Haringey Council divide schools within the borough according to students' learning abilities.

(…)

Although this is 48 years after Francis Galton's death, I think it's safe to say that he would have approved of such a move.

In Galton's vision of a nation governed by eugenic principles, quantifying intelligence played a central role.

He argued that the most intelligent people should be supported and encouraged to reproduce, while the least intelligent people should be prevented from doing so.

In the 1920s, psychologists such as Charles Spearman and Cyril Burt embraced the idea of standardizing intelligence, making Galton's vision a reality by designing and developing standardized intelligence tests.

Burt's research into whether intelligence is inherited, what we now think of as the genetics of intelligence, formed the basis of the British formal education system with the introduction of the 11+ exam.

11+ was a life-defining exam.

If you received high scores and were considered intelligent, you could enter a prestigious grammar school.

The important grammar here was, of course, Latin, and being educated at a grammar school was a fairly sure path to future academic success.

--- p.67~81, from Chapter 2, “Knowledge is Power”

The 'Inca Paradox' refers to the puzzling anthropological phenomenon that the Incas built a civilization with all the necessary complexities, such as architecture, engineering, and bureaucracy, without any system of recording anything.

If this sounds too strange to be true, that's because it isn't.

The Incas did not have a written language known to the rest of the world, namely paper, but they had their own unique writing system called khipu, which used knotted thread.

Until relatively recently, before anyone even thought about it, kipu was generally thought of as a basic system for counting and calculating.

As was the case with the early cuneiform writings of Mesopotamia.

However, research over the past decade has revealed that the Inca quipu was in fact a complex writing system, as complex as any writing system known worldwide today.

(…)

The Spanish conquistadors also knew about the quipu.

Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, an early "third culture child" born to an Inca mother and a Spanish conquistador father, said that the Incas "knotted everything they could count.

“Even the battles and fights, all the ambassadors who visited the Incas, and all the speeches and arguments they left behind,” he wrote in 1609.

The people who read the khippu bundles were the khipukamayuq, or 'knot keepers'.

They kept records so accurately and so accessible that the conquering Spanish considered them a definite threat.

About 25 years earlier, in 1583, the Spaniards had issued an order that all quipu in Peru were idolatrous and should be burned.

This was an easy way to erase records that contradicted the Spanish account of what happened in South America.

It was the same tactic used by Spanish conquistador Diego de Landa in 1562 when he ordered the burning of hundreds of Mayan magical objects, including 27 books.

It wasn't just Spanish guns and iron that defeated the Inca Empire.

Stories from Spain also joined in.

The Incas had a written language to record their history and pass it on to future generations.

It just wasn't the kind of thing we had in mind, and Spain just got rid of them all.

(…)

Even if you've never been interested in archaeology or anthropology, you've probably heard that aliens built the Great Pyramids in Egypt.

It's easy to dismiss stories like aliens, Atlantis, and the Earth being hollow as the uninformed ramblings of delusional people bordering on paranoia.

But in reality, these people are far from uninformed (they may be misinformed, but they are certainly overflowing with information).

Moreover, these ideas can be said to be, to some extent, a logical extension of actual archaeological and anthropological theories.

JG

If we accept the theories of Frazer, Thomas Babington Macaulay, and Hugh Blair, then it could be argued that uncivilized non-white non-Western peoples did not possess the intellectual capacity or technology to build the cities and monuments that they made their homes.

European scholars once thought that Great Zimbabwe (a 14th-century fortress city between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers, once home to an estimated 18,000 people) was a replica of the Queen of Sheba's palace in Jerusalem.

This was because Africans were thought to be incapable of handling such complex structures and engineering techniques.

When German explorer Carl Maho visited Great Zimbabwe in 1871, he argued that the site was more likely built not by local people but by biblical people who lived 1,500 years earlier and 8,000 kilometers away.

He wrote:

“There must have once been a civilized nation there.” And of course, this civilization could not have been in Africa.

Such a view implies racism, and it would never be made about past Western civilization.

No one claims that aliens built the temples of Ephesus in modern-day Turkey, the Parthenon in Athens, or the Colosseum in Rome.

On the other side of the coin of racism, there are researchers who dedicate their lives to finding lost ancient white people, believing that since such early civilizations are so prevalent, there must have been white people 'out there'.

--- p.111~117, from Chapter 3, “The Pen is Mightier than the Sword”

Like concepts like 'nation' or 'democracy', the idea that time can be manipulated is a relatively recent development.

This dates back to the Industrial Revolution, a period of development that took place in the 19th century.

In Britain, for example, millions of people have abandoned farming and rural life for urban life and industrial jobs.

Above all, the pay was much better.

Industrialization was a key development in Western history.

This was possible largely due to slave labor and the profits made from colonies around the world.

Colonists served first as a labor force, providing access to raw materials needed for manufacturing, and then as a market for finished goods.

It was a good way to bring endless profits and development.

Of course, that is, provided the colonies do not disappear (and, as we have come to admit belatedly, provided the raw materials do not run out).

Manufacturing, which emerged in the form of a factory system, did not simply revolutionize the economy.

This manufacturing industry has completely changed the way people work.

Before industrialization, people had a certain degree of flexibility in managing their work, and by extension, their leisure time.

Work was seasonal and depended on the weather, crops, and hours of daylight.

People could spend their time as they pleased, even splitting the night into two sleep periods, with a few hours awake in between.

As the factory-based manufacturing system took hold, people were expected to work, so to speak, 24 hours a day.

We are familiar with the history of those exploited within this system, industrial workers, especially many child workers, who toiled under overwork, lost fingers and arms, and were sacrificed to machines and the thirst for profit. But workers also lost something else.

They have lost the freedom and ability to govern their time and, by extension, themselves.

(…)

From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, Western societies squeezed workers and their working hours ever more for efficiency and profit.

This was possible in large part because of one man who, in the 1920s, first in the United States and then throughout the industrialized West, had the factory owners under his thumb.

His name was Frederick Winslow Taylor.

He was one of the first management consultants in history.

His employers nicknamed him "Speedy Taylor."

Like John Henry Belleville, he created a new profession for himself with the help of his watch.

He came out to the factory and watched carefully as the workers went about their work.

The main tool Taylor used in business was a stopwatch.

He was very meticulous about measuring the time people spent completing individual elements of a task.

No physical element of the work process escaped his eyes.

Taylor worshipped at the altar of efficiency.

The goal was to find the best way to get the job done in as little time as possible.

His innovations in the field of labor research and management earned him the reputation of "the father of scientific management."

(…)

And Taylor's ideas have been the metaphorical foundation of all business schools from that time to the present.

As with so many other problems, the solution is science.

Imperialism treated colonists as a source of raw materials and new markets, while Taylor's efficiency paradigm treated workers everywhere as machines.

The workers quickly noticed this.

The year the book was published, Taylor was giving a speech at the Boston Central Labor Union when a union member pulled him aside.

He said this:

“You might call it scientific management, but I call it scientific driving.” Taylor’s methods may have increased efficiency and productivity, but they also drove people to the brink of ruin.

By the time workers decided to take action to prevent exploitation in this way, it was already too late.

Scientific management has permeated mainstream Western thinking and continues to do so.

Whether we seek greater efficiency, reject efficiency, or escape it, we are constantly obsessed with efficiency.

As was evident throughout the colonized territories, Taylor's thinking was inherently grounded in the idea that some workers were superior to others.

It was a flawed and exploitative system, but those who did not fit into the system were treated as unfit human beings.

Throughout the history of Western civilization, this idea has expanded across space and time.

It was the colonial rulers who decided what and where was civilized, and they defined civilization within their own framework.

They claim that they are not only more powerful, but also more socially, culturally, and intellectually advanced than the rest of the world.

(…) Western civilization is, in many ways (at least in ten aspects, as we will see), a case of successful branding that suppresses reality.

A look into the history of the West reveals that Western civilization is not simply a product, but a process.

The 'mission of civilization' was the vision and justification of the nations that established colonies.

The European powers did not simply appropriate the rest of the world; they completely reshaped it within the framework of the civilization they had created.

(…) Rather than simply exposing the lies behind these notions, I want to try to understand how we were so easily fooled into believing these notions were true in the first place.

We will learn what the words we use without much thought actually mean and what claims are implied in those terms.

--- p.14~17, from “Introductory Remarks”

Frazer's work solidified established ideas about cultural development, progress, and civilization.

Needless to say, early versions of this idea were closely tied to the scientific concept of race.

As with taxonomy and the classification of life on Earth, observations of physical appearance continue to be closely linked to more abstract qualities such as intelligence and behavior.

James Cowles-Pritchard, the most important British folklorist of the 19th century, believed that the white skin and greater intelligence of Europeans were the direct result of a civilizing process that darker-skinned peoples had not yet undergone.

Henri de Saint-Simon had a less positive view of the possibility of civilization change.

He justified France's reinstitution of slavery by saying that black Africans could not attain the same high intelligence as white Europeans.

Anthropologist Frederick Farrar also agreed.

In his 1866 lecture, "Aptitude of Races," Farrar divided the world's people into three groups.

There were barbarian groups, semi-civilized groups, and civilized groups.

He described those he considered savages as having “no past or future,” “no redemption,” and being frozen in time like “living fossils,” beyond anything that could be done about them.

(…) Science has become a frame for understanding the world, and within it, we humans have become a subject of discussion.

And so, a place was created for civilized people who claimed to be worthy of continuing to ask discussion questions.

(…) The result of the powerful combination of science, race, and civilization was that non-Westerners were, from a scientific perspective, rotten to the core, even when they might simply be 'read' as behaving incomprehensibly or incomprehensibly.

As a result, the answer to the question of humanity can now only be proven in one specific way.

Only through the methods of science itself.

When people from non-Western regions, especially those who are not considered racially white, say that they are human, we are unlikely to take that at face value.

It is not our responsibility to believe them, but their responsibility to prove that this is true.

Race is not a subject of debate, and by extension, arguing with racists is virtually pointless.

Racists would have you believe that race really exists, and science is their alibi.

Science allows racists to keep a safe distance.

The saying, "Never take anyone's word for it" may seem obvious, but let's look a little closer at the broader historical context.

It then becomes clear that the foundations of science, and particularly the foundations of racial science, serve a deeper purpose.

Being white and being civilized simultaneously means being powerful.

--- p.45~48, from Chapter 1, “Don’t Take Anyone’s Words at Face”

It is known that in England the term 'classics' first came to mean the study of ancient authors by wealthy young people around 1684.

This was because a group calling themselves “some young men educated at Hatton Garden” published their own translation of the work of Eutropius, a 4th-century official who wrote the history of the founding of Rome.

This was a time when London was rising from the ashes of the Great Fire of 1666 like a phoenix, bearing the spirit of empire, and the idea that, as Francis Bacon put it, "knowledge is power" was firmly established.

Louise Madewell, a teacher at Hatton Garden, wrote in the book's preface that if the British were more serious about education, "the sleeping talents of England would awaken of their own accord."

Education was not simply a matter of expanding the mental world.

Education was also a key tool in broadening the horizons of the British Empire and solidifying its power.

(…)

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a series of leaked documents exposed the inferior counterfeiting within the British education system.

One of these is the report 'Harringay Comprehensive Secondary School' (1969), commonly known as the Dalton Report after its author.

The report sparked disappointment and anger in black communities in north London.

Schools with a large number of West Indian students were said to have to lower their standards.

This was because these children were generally thought to have much lower IQs than white British students.

And a follow-up report, the 'Report of the Education Committee on Integrated Education', recommended that Haringey Council divide schools within the borough according to students' learning abilities.

(…)

Although this is 48 years after Francis Galton's death, I think it's safe to say that he would have approved of such a move.

In Galton's vision of a nation governed by eugenic principles, quantifying intelligence played a central role.

He argued that the most intelligent people should be supported and encouraged to reproduce, while the least intelligent people should be prevented from doing so.

In the 1920s, psychologists such as Charles Spearman and Cyril Burt embraced the idea of standardizing intelligence, making Galton's vision a reality by designing and developing standardized intelligence tests.

Burt's research into whether intelligence is inherited, what we now think of as the genetics of intelligence, formed the basis of the British formal education system with the introduction of the 11+ exam.

11+ was a life-defining exam.

If you received high scores and were considered intelligent, you could enter a prestigious grammar school.

The important grammar here was, of course, Latin, and being educated at a grammar school was a fairly sure path to future academic success.

--- p.67~81, from Chapter 2, “Knowledge is Power”

The 'Inca Paradox' refers to the puzzling anthropological phenomenon that the Incas built a civilization with all the necessary complexities, such as architecture, engineering, and bureaucracy, without any system of recording anything.

If this sounds too strange to be true, that's because it isn't.

The Incas did not have a written language known to the rest of the world, namely paper, but they had their own unique writing system called khipu, which used knotted thread.

Until relatively recently, before anyone even thought about it, kipu was generally thought of as a basic system for counting and calculating.

As was the case with the early cuneiform writings of Mesopotamia.

However, research over the past decade has revealed that the Inca quipu was in fact a complex writing system, as complex as any writing system known worldwide today.

(…)

The Spanish conquistadors also knew about the quipu.

Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, an early "third culture child" born to an Inca mother and a Spanish conquistador father, said that the Incas "knotted everything they could count.

“Even the battles and fights, all the ambassadors who visited the Incas, and all the speeches and arguments they left behind,” he wrote in 1609.

The people who read the khippu bundles were the khipukamayuq, or 'knot keepers'.

They kept records so accurately and so accessible that the conquering Spanish considered them a definite threat.

About 25 years earlier, in 1583, the Spaniards had issued an order that all quipu in Peru were idolatrous and should be burned.

This was an easy way to erase records that contradicted the Spanish account of what happened in South America.

It was the same tactic used by Spanish conquistador Diego de Landa in 1562 when he ordered the burning of hundreds of Mayan magical objects, including 27 books.

It wasn't just Spanish guns and iron that defeated the Inca Empire.

Stories from Spain also joined in.

The Incas had a written language to record their history and pass it on to future generations.

It just wasn't the kind of thing we had in mind, and Spain just got rid of them all.

(…)

Even if you've never been interested in archaeology or anthropology, you've probably heard that aliens built the Great Pyramids in Egypt.

It's easy to dismiss stories like aliens, Atlantis, and the Earth being hollow as the uninformed ramblings of delusional people bordering on paranoia.

But in reality, these people are far from uninformed (they may be misinformed, but they are certainly overflowing with information).

Moreover, these ideas can be said to be, to some extent, a logical extension of actual archaeological and anthropological theories.

JG

If we accept the theories of Frazer, Thomas Babington Macaulay, and Hugh Blair, then it could be argued that uncivilized non-white non-Western peoples did not possess the intellectual capacity or technology to build the cities and monuments that they made their homes.

European scholars once thought that Great Zimbabwe (a 14th-century fortress city between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers, once home to an estimated 18,000 people) was a replica of the Queen of Sheba's palace in Jerusalem.

This was because Africans were thought to be incapable of handling such complex structures and engineering techniques.

When German explorer Carl Maho visited Great Zimbabwe in 1871, he argued that the site was more likely built not by local people but by biblical people who lived 1,500 years earlier and 8,000 kilometers away.

He wrote:

“There must have once been a civilized nation there.” And of course, this civilization could not have been in Africa.

Such a view implies racism, and it would never be made about past Western civilization.

No one claims that aliens built the temples of Ephesus in modern-day Turkey, the Parthenon in Athens, or the Colosseum in Rome.

On the other side of the coin of racism, there are researchers who dedicate their lives to finding lost ancient white people, believing that since such early civilizations are so prevalent, there must have been white people 'out there'.

--- p.111~117, from Chapter 3, “The Pen is Mightier than the Sword”

Like concepts like 'nation' or 'democracy', the idea that time can be manipulated is a relatively recent development.

This dates back to the Industrial Revolution, a period of development that took place in the 19th century.

In Britain, for example, millions of people have abandoned farming and rural life for urban life and industrial jobs.

Above all, the pay was much better.

Industrialization was a key development in Western history.

This was possible largely due to slave labor and the profits made from colonies around the world.

Colonists served first as a labor force, providing access to raw materials needed for manufacturing, and then as a market for finished goods.

It was a good way to bring endless profits and development.

Of course, that is, provided the colonies do not disappear (and, as we have come to admit belatedly, provided the raw materials do not run out).

Manufacturing, which emerged in the form of a factory system, did not simply revolutionize the economy.

This manufacturing industry has completely changed the way people work.

Before industrialization, people had a certain degree of flexibility in managing their work, and by extension, their leisure time.

Work was seasonal and depended on the weather, crops, and hours of daylight.

People could spend their time as they pleased, even splitting the night into two sleep periods, with a few hours awake in between.

As the factory-based manufacturing system took hold, people were expected to work, so to speak, 24 hours a day.

We are familiar with the history of those exploited within this system, industrial workers, especially many child workers, who toiled under overwork, lost fingers and arms, and were sacrificed to machines and the thirst for profit. But workers also lost something else.

They have lost the freedom and ability to govern their time and, by extension, themselves.

(…)

From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, Western societies squeezed workers and their working hours ever more for efficiency and profit.

This was possible in large part because of one man who, in the 1920s, first in the United States and then throughout the industrialized West, had the factory owners under his thumb.

His name was Frederick Winslow Taylor.

He was one of the first management consultants in history.

His employers nicknamed him "Speedy Taylor."

Like John Henry Belleville, he created a new profession for himself with the help of his watch.

He came out to the factory and watched carefully as the workers went about their work.

The main tool Taylor used in business was a stopwatch.

He was very meticulous about measuring the time people spent completing individual elements of a task.

No physical element of the work process escaped his eyes.

Taylor worshipped at the altar of efficiency.

The goal was to find the best way to get the job done in as little time as possible.

His innovations in the field of labor research and management earned him the reputation of "the father of scientific management."

(…)

And Taylor's ideas have been the metaphorical foundation of all business schools from that time to the present.

As with so many other problems, the solution is science.

Imperialism treated colonists as a source of raw materials and new markets, while Taylor's efficiency paradigm treated workers everywhere as machines.

The workers quickly noticed this.

The year the book was published, Taylor was giving a speech at the Boston Central Labor Union when a union member pulled him aside.

He said this:

“You might call it scientific management, but I call it scientific driving.” Taylor’s methods may have increased efficiency and productivity, but they also drove people to the brink of ruin.

By the time workers decided to take action to prevent exploitation in this way, it was already too late.

Scientific management has permeated mainstream Western thinking and continues to do so.

Whether we seek greater efficiency, reject efficiency, or escape it, we are constantly obsessed with efficiency.

As was evident throughout the colonized territories, Taylor's thinking was inherently grounded in the idea that some workers were superior to others.

It was a flawed and exploitative system, but those who did not fit into the system were treated as unfit human beings.

Throughout the history of Western civilization, this idea has expanded across space and time.

--- p.208~213, from Chapter 6, “Time is Money”

Publisher's Review

Planted in the deepest part of my mind

Uproot the frame of power!

'Never take anyone's word for it', 'Knowledge is power', 'Time is money'.

“The pen is mightier than the sword”… These words, which everyone has likely heard, are accepted as unquestionable wisdom in our society.

Universal beliefs such as the 'rationality of science,' 'the power of education,' 'the importance of time,' and 'the influence of writing' are achievements of modern civilization and are shared as core values of our society.

But can we simply consider this as purely correct? Rather, isn't it possible to accept it so uncritically, as if it were a given, that we hinder ourselves from examining the historical significance embedded within it? "Ten Frames That Moved the World" begins with this question in mind.

We explore the ten core values shared as achievements of modern civilization and long-held beliefs, examining the framework of "power" hidden within these powerful words and their impact on history and our thinking.

From science, education, and democracy to time, art, and death

Defeat the ten frames and regain your own perspective on the world!

Science is the pinnacle of value-neutral reason, education is the center of the liberal arts that makes us human, time is a resource that can be efficiently utilized to create value, and writing is a magical tool capable of expressing all thoughts and events… These are our universal beliefs, and we consider acquiring them the foundation of civilization.

A society or people who do not naturally have this are considered barbaric and uncivilized.

The fundamental question arises here.

Where do the concepts so deeply ingrained in our minds—science, education, writing, time—come from? Where do the standards of civilization we've established come from? Who established them, and who, crucially, benefits from them?

Values that seem splendid and obvious took shape and developed with the rise of imperialism and capitalism, and were used as decisive tools in the process of the 'West' dominating the world.

At the center of the power game they have devised is ‘civilization and barbarism.’

This book explores the creation of the ten core values that underpin modern civilization, revealing how Western powers have used their frameworks to divide the world into civilization and barbarism, and to unfold a history of oppression and exploitation.

Who monopolizes science? Who determines what constitutes "classic," and how did it become a vision of imperialism? What is the hidden meaning behind the claim that the pyramids were built by aliens? Why does time seem to grasp us so uncontrollably? Why was the Incan script "quipu" erased from history? By raising these questions, the author reveals how deeply the massive structures of oppression and exploitation created by the Western world are engraved in history and in our minds.

Do we have the power to dream of another world now?

If you don't change the frame, reading any history book is useless!

It is a well-known fact that South Korea began its modern history during the Japanese colonial period, and after liberation, it experienced the Korean War, was divided into North and South, and its social system was formed based on Western civilization imported from the United States.

It is unfortunate, but undeniable, that the ideas and values of the Western world, accepted under the guise of advanced civilization, are deeply rooted in Korean society and have not yet been completely eradicated.

This book questions whether, in the process of modernization, we have internalized even the framework of the Western world and lost our own identity. It proposes that we now completely break free from that framework and regain the power to imagine a different world.

Perhaps reading this book is more difficult than enjoyable.

As you read each page, you may find yourself going through a process of overturning and denying beliefs you have accepted without question.

However, the author says that this is a way to get your own perspective on history, outside the frame of power.

Now, here lies the true reason and new joy of reading history.

Uproot the frame of power!

'Never take anyone's word for it', 'Knowledge is power', 'Time is money'.

“The pen is mightier than the sword”… These words, which everyone has likely heard, are accepted as unquestionable wisdom in our society.

Universal beliefs such as the 'rationality of science,' 'the power of education,' 'the importance of time,' and 'the influence of writing' are achievements of modern civilization and are shared as core values of our society.

But can we simply consider this as purely correct? Rather, isn't it possible to accept it so uncritically, as if it were a given, that we hinder ourselves from examining the historical significance embedded within it? "Ten Frames That Moved the World" begins with this question in mind.

We explore the ten core values shared as achievements of modern civilization and long-held beliefs, examining the framework of "power" hidden within these powerful words and their impact on history and our thinking.

From science, education, and democracy to time, art, and death

Defeat the ten frames and regain your own perspective on the world!

Science is the pinnacle of value-neutral reason, education is the center of the liberal arts that makes us human, time is a resource that can be efficiently utilized to create value, and writing is a magical tool capable of expressing all thoughts and events… These are our universal beliefs, and we consider acquiring them the foundation of civilization.

A society or people who do not naturally have this are considered barbaric and uncivilized.

The fundamental question arises here.

Where do the concepts so deeply ingrained in our minds—science, education, writing, time—come from? Where do the standards of civilization we've established come from? Who established them, and who, crucially, benefits from them?

Values that seem splendid and obvious took shape and developed with the rise of imperialism and capitalism, and were used as decisive tools in the process of the 'West' dominating the world.

At the center of the power game they have devised is ‘civilization and barbarism.’

This book explores the creation of the ten core values that underpin modern civilization, revealing how Western powers have used their frameworks to divide the world into civilization and barbarism, and to unfold a history of oppression and exploitation.

Who monopolizes science? Who determines what constitutes "classic," and how did it become a vision of imperialism? What is the hidden meaning behind the claim that the pyramids were built by aliens? Why does time seem to grasp us so uncontrollably? Why was the Incan script "quipu" erased from history? By raising these questions, the author reveals how deeply the massive structures of oppression and exploitation created by the Western world are engraved in history and in our minds.

Do we have the power to dream of another world now?

If you don't change the frame, reading any history book is useless!

It is a well-known fact that South Korea began its modern history during the Japanese colonial period, and after liberation, it experienced the Korean War, was divided into North and South, and its social system was formed based on Western civilization imported from the United States.

It is unfortunate, but undeniable, that the ideas and values of the Western world, accepted under the guise of advanced civilization, are deeply rooted in Korean society and have not yet been completely eradicated.

This book questions whether, in the process of modernization, we have internalized even the framework of the Western world and lost our own identity. It proposes that we now completely break free from that framework and regain the power to imagine a different world.

Perhaps reading this book is more difficult than enjoyable.

As you read each page, you may find yourself going through a process of overturning and denying beliefs you have accepted without question.

However, the author says that this is a way to get your own perspective on history, outside the frame of power.

Now, here lies the true reason and new joy of reading history.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 7, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 408 pages | 518g | 140*210*21mm

- ISBN13: 9791164052547

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)