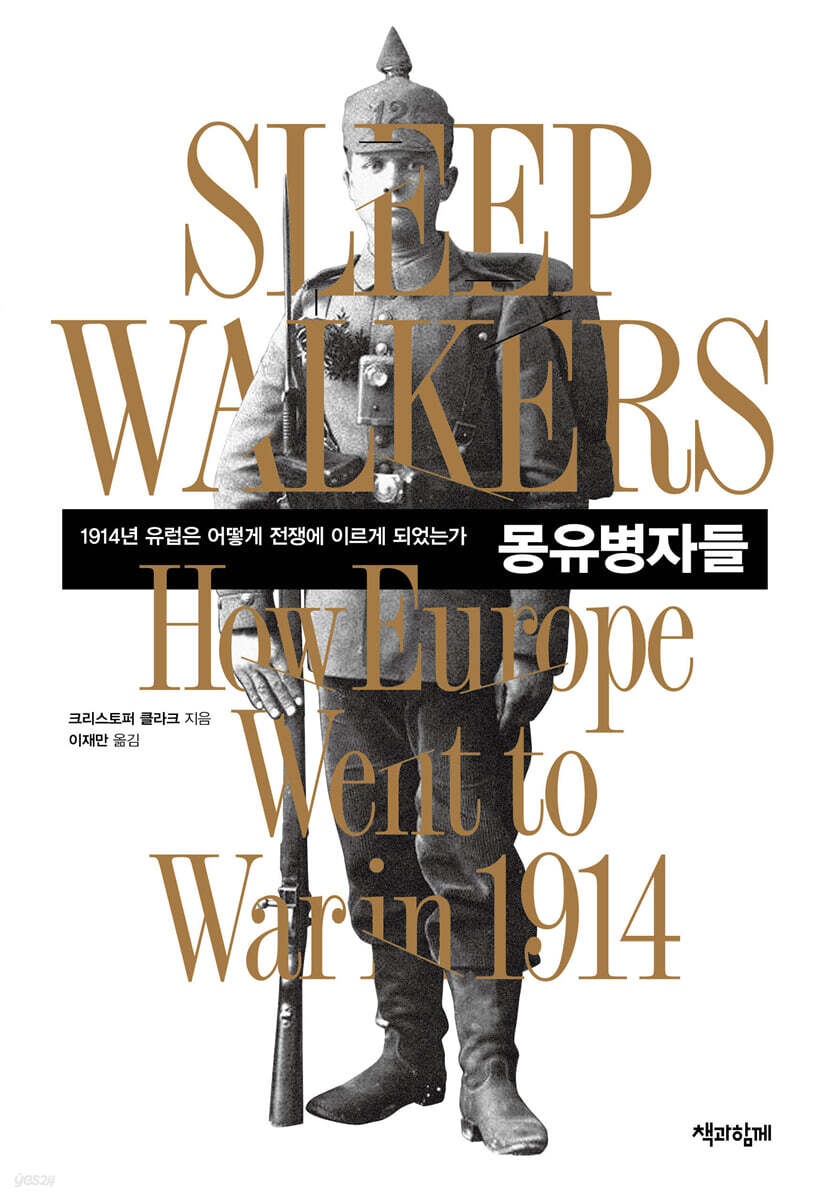

sleepwalkers

|

Description

Book Introduction

“The protagonists of 1914 were blinded by dreams, unable to see with their eyes wide open.

They were sleepwalkers, unaware of the horror they were about to unleash upon the world.”

A book that became a hot topic when UN Under-Secretary-General Feltman gave it to North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong-ho in December 2017.

Among the books published to mark the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, this book was hailed as a “masterpiece” and was considered a new standard work.

The Korean edition of 『The Sleepwalkers』 has finally been published.

Before World War I, there was no national executive in Europe that actively planned war.

Any country has said that it has 'defensive' intentions towards me and 'offensive' intentions towards the other country.

Key decision-makers failed to anticipate the consequences of their self-serving efforts, and executives with low levels of mutual trust and high levels of hostility and paranoia interacted at a rapid-fire pace, oblivious to each other's intentions, resulting in the worst-case scenario.

In order to understand their decisions from their perspective as much as possible, the author focuses on 'how' the war happened, not 'why' it happened.

They were not mere accomplices in the impersonal forward movement of history, puppets moved by the logic of the system, but protagonists, full of agency and capable of realizing a sufficiently different future.

War was not an inevitable outcome, but the culmination of a chain of decisions they made.

The world situation in the 21st century is very similar to that of Europe a hundred years ago.

Since the end of the Cold War, the stable global bipolar system has given way to a complex and unpredictable array of powers, with empires declining and new powers rising.

Readers who follow the course of the crisis in the summer of 1914 will undoubtedly recognize its vivid modernity.

The story in this book will provide crucial insights, especially for Korean readers who have lived with the possibility of accidental conflict.

They were sleepwalkers, unaware of the horror they were about to unleash upon the world.”

A book that became a hot topic when UN Under-Secretary-General Feltman gave it to North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong-ho in December 2017.

Among the books published to mark the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, this book was hailed as a “masterpiece” and was considered a new standard work.

The Korean edition of 『The Sleepwalkers』 has finally been published.

Before World War I, there was no national executive in Europe that actively planned war.

Any country has said that it has 'defensive' intentions towards me and 'offensive' intentions towards the other country.

Key decision-makers failed to anticipate the consequences of their self-serving efforts, and executives with low levels of mutual trust and high levels of hostility and paranoia interacted at a rapid-fire pace, oblivious to each other's intentions, resulting in the worst-case scenario.

In order to understand their decisions from their perspective as much as possible, the author focuses on 'how' the war happened, not 'why' it happened.

They were not mere accomplices in the impersonal forward movement of history, puppets moved by the logic of the system, but protagonists, full of agency and capable of realizing a sufficiently different future.

War was not an inevitable outcome, but the culmination of a chain of decisions they made.

The world situation in the 21st century is very similar to that of Europe a hundred years ago.

Since the end of the Cold War, the stable global bipolar system has given way to a complex and unpredictable array of powers, with empires declining and new powers rising.

Readers who follow the course of the crisis in the summer of 1914 will undoubtedly recognize its vivid modernity.

The story in this book will provide crucial insights, especially for Korean readers who have lived with the possibility of accidental conflict.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Translator's Note

Acknowledgements

1914 map of Europe

introduction

Part 1: The Road to Sarajevo

Chapter 1: Ghosts of Serbia

Belgrade Assassination | 'Irresponsible Elements' | Mental Map | Breakup | Escalation | Three Turkish Wars | Archduke Assassination Plot | Nikola Pašić Responds

Chapter 2: An Empire Without Character

Conflict and Equilibrium | Chess Players | Lies and Forgery | Deceptive Calm | Hawks and Doves

Part 2: The Divided Continent

Chapter 3: Polarization in Europe, 1887–1907

Dangerous Liaisons: The Franco-Russian Alliance | The Paris Judgment | Britain Ends Neutrality | Late-Blooming Imperial Germany | A Turning Point? | Drawing the Devil on the Wall

Chapter 4: The Many Voices of European Foreign Policy

The Sovereign Decision-Makers | Who Ruled in St. Petersburg? | Who Ruled in Paris? | Who Ruled in Berlin? | Sir Edward Grey's Precarious Predominance | The Agadir Crisis of 1911 | Soldiers and Civilians | The Press and Public Opinion | The Fluidity of Power

Chapter 5: The Tangled Balkans

The Libyan Raid | The Balkan Melee | The Hesitation | The Balkan Crisis of the Winter of 1912–1913 | Bulgaria or Serbia | Austria's Predicament | The Balkanization of the Franco-Russian Alliance | Paris Accelerating | Poincaré Under Pressure

Chapter 6: The Last Chance: Détente and Danger, 1912–1914

The Limits of Détente | 'It's Now or Never' | Germans on the Bosphorus | Balkan Opening Scenario | A Crisis of Masculinity? | How Open Was the Future?

Part 3 Crisis

Chapter 7: The Sarajevo Murders

Assassination | Moments Memorized Like Pictures | The Investigation Begins | Serbia's Response | What Should Be Done?

Chapter 8: The Spreading Ripples

Foreign Reaction | Count Hoyos Dispatched to Berlin | Until Austria Issues its Ultimatum | The Death of Gartwig

Chapter 9 The French in St. Petersburg

Count de Robbins changes trains | Poincaré boards a ship bound for Russia | Poker game

Chapter 10: Ultimatum

Austria demands | Serbia responds | 'Local war' begins

Chapter 11 Warning Shot

The Hard Line Dominates | "This Time It's War" | The Russian Situation

Chapter 12: The Last Days

A strange light descends on the map of Europe | Poincaré returns to Paris | Russia mobilizes its troops | Plunging into darkness | "There must have been some misunderstanding" | The ordeal of Paul Cambon | Britain intervenes | Belgium | Military boots

conclusion

main

Search

Acknowledgements

1914 map of Europe

introduction

Part 1: The Road to Sarajevo

Chapter 1: Ghosts of Serbia

Belgrade Assassination | 'Irresponsible Elements' | Mental Map | Breakup | Escalation | Three Turkish Wars | Archduke Assassination Plot | Nikola Pašić Responds

Chapter 2: An Empire Without Character

Conflict and Equilibrium | Chess Players | Lies and Forgery | Deceptive Calm | Hawks and Doves

Part 2: The Divided Continent

Chapter 3: Polarization in Europe, 1887–1907

Dangerous Liaisons: The Franco-Russian Alliance | The Paris Judgment | Britain Ends Neutrality | Late-Blooming Imperial Germany | A Turning Point? | Drawing the Devil on the Wall

Chapter 4: The Many Voices of European Foreign Policy

The Sovereign Decision-Makers | Who Ruled in St. Petersburg? | Who Ruled in Paris? | Who Ruled in Berlin? | Sir Edward Grey's Precarious Predominance | The Agadir Crisis of 1911 | Soldiers and Civilians | The Press and Public Opinion | The Fluidity of Power

Chapter 5: The Tangled Balkans

The Libyan Raid | The Balkan Melee | The Hesitation | The Balkan Crisis of the Winter of 1912–1913 | Bulgaria or Serbia | Austria's Predicament | The Balkanization of the Franco-Russian Alliance | Paris Accelerating | Poincaré Under Pressure

Chapter 6: The Last Chance: Détente and Danger, 1912–1914

The Limits of Détente | 'It's Now or Never' | Germans on the Bosphorus | Balkan Opening Scenario | A Crisis of Masculinity? | How Open Was the Future?

Part 3 Crisis

Chapter 7: The Sarajevo Murders

Assassination | Moments Memorized Like Pictures | The Investigation Begins | Serbia's Response | What Should Be Done?

Chapter 8: The Spreading Ripples

Foreign Reaction | Count Hoyos Dispatched to Berlin | Until Austria Issues its Ultimatum | The Death of Gartwig

Chapter 9 The French in St. Petersburg

Count de Robbins changes trains | Poincaré boards a ship bound for Russia | Poker game

Chapter 10: Ultimatum

Austria demands | Serbia responds | 'Local war' begins

Chapter 11 Warning Shot

The Hard Line Dominates | "This Time It's War" | The Russian Situation

Chapter 12: The Last Days

A strange light descends on the map of Europe | Poincaré returns to Paris | Russia mobilizes its troops | Plunging into darkness | "There must have been some misunderstanding" | The ordeal of Paul Cambon | Britain intervenes | Belgium | Military boots

conclusion

main

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

A 21st-century reader reading the course of the crisis in the summer of 1914 will undoubtedly recognize its vivid modernity.

The crisis began with suicide bombers and motorcades.

Behind the Sarajevo bombings was a self-proclaimed terrorist organization that praised sacrifice, death, and revenge.

However, this organization was an extraterritorial organization with no clear geographical or political location.

Scattered across the Balkan Peninsula in the form of cell organizations that transcended political boundaries, were unaccountable for their actions, had no apparent ties to any sovereign government, and were clearly extremely difficult to detect outside the organization.

In some ways, one could say that the July 1914 crisis is closer to us today, and appears more vivid, than it did in the 1980s.

Since the end of the Cold War, the stable global bipolar system has given way to a multitude of more complex and unpredictable powers, with empires declining and new powers rising (a global situation that is worth comparing to Europe in 1914).

This shift in perspective prompts a rethinking of the story of how Europe came to war.

Taking on this challenge does not mean embracing a shallow presentism that reconstructs the past to suit the tastes of the present.

Rather, it is an acknowledgement that there are features of the past that can be seen more clearly from our changed perspective.

--- From the introduction

This book is divided into three parts.

Part 1 focuses on Serbia and Austria-Hungary, whose feud ignited war, and follows their interactions up to the eve of the Sarajevo assassination.

Part 2 breaks the narrative and asks four questions in four chapters:

How did Europe become polarized into two opposing camps? How did European states formulate their foreign policies? How did the Balkans—a peripheral region far from Europe's centers of power and wealth—become the setting for such a profound crisis? How did the international system, seemingly entering an era of détente, spiral into all-out war? Part 3 offers a narrative account of the July Crisis itself, beginning with the assassination in Sarajevo and examining the interactions between key decision-making centers, illuminating the calculations, misunderstandings, and decisions that escalated the crisis.

The central argument of this book is that the events of July 1914 can only be properly understood by uncovering the paths taken by key decision-makers.

To achieve this, we need to go beyond simply revisiting the series of international "crises" that preceded the war and understand how these events were experienced, how they were woven into the narratives that structured perception, and how they drove action.

Why did those who made the decisions that led Europe to war act the way they did and perceive the situation the way they did? How did the individual fears and forebodings found in numerous sources connect to the often arrogant and bombastic attitudes of these same individuals? Why were pre-war exoticisms like the Albanian question and the "Bulgarian loan" so significant, and how were they perceived by those in power? When decision-makers discussed the international situation and external threats, were they seeing something substantive, or were they projecting their own fears and desires onto the enemy? Or was it both? My goal is to reconstruct, as vividly as possible, the highly dynamic "decision-making positions" occupied by key actors before and during the summer of 1914.

--- From the introduction

The king or emperor was the only point where the separate chains of command converged.

If the monarch failed to perform the unifying function, for example, if he failed to remedy the constitution's shortcomings, the system ran the risk of being unable to make decisions or making inconsistent decisions.

And continental monarchs often failed to fulfill this role.

No, to be more precise, he refused to perform such a role from the beginning.

This is because he tried to maintain initiative and superiority within the system by dealing separately with key executive officials.

And this attitude ultimately had a negative impact on the policy-making process.

In an environment where decisions made by a minister can be overturned or undermined by colleagues or competitors, ministers often struggle to judge “how their activities fit into the bigger picture.”

The resulting general confusion encouraged ministers, bureaucrats, military commanders, and policy experts to believe that they could assert their own opinions but were not held accountable for the consequences of their policies.

At the same time, the pressure to curry favor with the monarch fostered an atmosphere of competition and flattery, hindering interdepartmental consultation for more balanced decision-making.

The result was a culture of factionalism and rhetoric that would bear dangerous fruit in July 1914.

---From "The Many Voices of European Foreign Policy"

Even if we assume that the prewar European powers had a cohesive executive body that pursued unified and consistent goals, conceived and managed their foreign policies, reconstructing their relationships is a daunting task.

Because the relationship between any two great powers cannot be fully understood without considering their relationships with all the other great powers.

However, the reality in Europe between 1903 and 1914 was more complex than the 'international relations' model suggests.

In a system characterized by weak cabinet cohesion, the monarch's unpredictable interventions, ambiguous civil-military relations, and the hostile rivalry of key political figures, combined with the occasional crisis and heightened tensions caused by security concerns and the incitement of a critical mass media, international relations experienced unprecedented levels of uncertainty during this period.

The resulting erratic policies and confusing signals made it difficult for historians and even politicians on the eve of war to interpret the international situation.

It would be a mistake to overemphasize the view that focuses on the international situation.

All complex political executives, even authoritarian ones, experience internal conflict and volatility.

Literature on 20th-century American foreign relations describes at length the power struggles and intrigues within the government.

As Andrew Preston shows in his excellent study of America's involvement in the Vietnam War, Lyndon B.

Johnson and John F.

Although President Kennedy was reluctant to go to war and the State Department generally opposed intervention, the smaller, more nimble National Security Council (NSC), operating outside of Congressional oversight, strongly supported entry into the war, narrowing the president's options for Vietnam until war was virtually inevitable.

But the situation in Europe before World War I was different (and worse) in one important respect.

Even if some internal conflicts arise, the U.S. executive branch is (from a constitutional perspective) a very clear-cut organization with ultimate responsibility for foreign policy decisions clearly in the hands of the president.

Prewar European governments did not do so.

For the British government, there was a persistent question as to whether Foreign Secretary Gray had the right to make promises to foreign governments without consulting the Cabinet or Parliament.

In fact, this doubt was so strong that Gray was unable to clearly state his intentions.

The situation in France was even more unclear.

The balance of power between the Foreign Office, the Cabinet, and the President remained unsettled, and even the adroit and decisive Poincaré faced efforts in the spring of 1914 to exclude him entirely from the policy-making process.

In Austria-Hungary, and to a lesser extent in Russia, the power to shape foreign policy floated around a multi-layered structure of loosely connected political elites, concentrating in different parts of the system depending on who could form the most effective and cohesive bonds.

In such cases, as in Germany, the existence of a 'supreme' sovereign, rather than clarifying the power relations within the system, has rather blurred them.

This is not a matter of reconstructing the reasoning of two superpowers who carefully considered their options, as during, say, the Cuban Missile Crisis, but of understanding the rapid-fire exchanges between executives with low levels of trust and confidence (even among allies) and high levels of hostility and paranoia, often without a clear understanding of each other's intentions.

The inherent volatility of these international relations is exacerbated by the fluidity of power within each executive branch and the tendency for power to shift from one central point of the system to another.

The internal friction and debate within the Foreign Office may have been beneficial in that it allowed for questions and dissent that would have been suppressed in a more rigid policy environment.

But clearly the risks outweighed the benefits.

When hawks dominate the signaling process on both sides of a potential conflict, as happened during the Agadir crisis or after June 28, 1914, crises can escalate quickly and unpredictably.

---From "The Fluidity of Power" among the many voices of European foreign policy

We must make an important distinction.

French or Russian strategists never engaged in plans to launch a war of aggression against their allies.

What we are dealing with now is a scenario, not a plan itself.

Even so, policymakers in both countries seemed surprisingly indifferent to the potential impact their actions would have on Germany.

French policymakers knew how much the balance of military threat had tilted against Germany.

A report from the French General Staff in June 1914 noted with satisfaction that “the military situation has changed to the disadvantage of Germany,” and the British military assessment was not much different.

But because they believed their actions were entirely defensive and intended only to be offensive against the enemy, key policymakers did not seriously consider the possibility that their decisions would reduce Berlin's options.

It was a stark example of what international relations theorists call the "security dilemma," a situation in which actions taken by one state to strengthen its own security "make other states anxious and force them to prepare for the worst."

---From "The Last Chance: Détente and Danger, 1912-1914"

Something roughly similar happens when we reflect on historical events, especially ones as catastrophic as World War I.

Once such events occur, they give us (or seem to give us) the feeling that they were inevitable.

This process takes place on several levels.

We can find this process in the letters, speeches, and memoirs of the key players in World War I.

They were quick to emphasize that there was no alternative, that war was 'inevitable' and therefore unstoppable.

Narratives that speak of inevitability like this appear in many forms.

Some simply shift the blame to other states or actors, others claim that the system itself has a war-prone nature, regardless of the will of individual actors, or even appeal to the impersonal forces of history or fate.

The search for the causes of World War I has dominated the relevant literature for nearly a century, reinforcing this trend.

As the causes discovered by thoroughly searching Europe over the decades before and after the war pile up like weights on a scale, the scale that had been tilted toward probability eventually tilts toward inevitability.

Contingency, choice, and agency disappear from view.

This is partly a question of perspective.

Looking back on the twists and turns of European international relations before 1914 from the distant future of the early 21st century, we cannot help but view it through the lens of later generations.

Denis Diderot described a well-composed painting as “a whole contained in a single perspective,” and to us, the events preceding World War I seem to compose themselves into something resembling such a picture.

Of course, if you try to fix this problem by fixating on contingency or suddenness, you are going down the wrong path.

More than anything, such an attempt merely replaces the problem of multi-decision with the problem of indecision, that is, the problem of war without cause.

While understanding why World War I might not have happened is important in itself, this insight must be balanced with an understanding of how and why the war actually happened.

---From "The Last Chance: Détente and Danger, 1912-1914"

[Germany] Underlying the calculations of key decision makers was a well-established and (as we can see today from looking back) flawed assumption: that Russia was unlikely to intervene.

It is not difficult to find reasons why the risk level was so absurdly misjudged.

One obvious reason was Russia's acceptance of Austria's ultimatum to Serbia in October 1913.

And at that time, as already mentioned, there was a deep-rooted idea that time was on Russia's side.

In Berlin, the Archduke's assassination was seen as an attack on the principles of monarchy, set in a political culture with a strong tendency towards regicide (a view also found in some British newspapers).

Even if Russia had been firmly committed to Pan-Slavism, it was difficult to imagine the Tsar siding with the 'regicides', as the Kaiser repeatedly insisted.

To all this must be added the eternal problem of interpreting the intentions of the Russian executive.

Germany did not realize how much the Austro-Serbian conflict was already part of the strategic thinking of the Franco-Russian alliance.

Germany failed to grasp how indifferent the two Western powers were to the question of who had provoked the conflict.

…Looking at it this way, Germany's strategy was not, strictly speaking, a strategy focused on risk, but rather a strategy aimed at revealing the true extent of the threat posed by Russia.

In other words, if Russia had chosen to mobilize against Germany, thereby triggering a continental war, it would have revealed not the danger posed by German actions, but Russia's strong determination to rebalance the European system through war.

From this somewhat pessimistic perspective, Germany was not taking a risk, but rather testing a threat.

This was the logic behind Bethmann's frequent references to the Russian threat in the months leading up to the outbreak of war.

---From "Spreading Ripples"

The outbreak of war in 1914 is not an Agatha Christie-style drama that ends with the murderer being found in a greenhouse, holding a smoking pistol and watching over a corpse.

There are no smoking guns in this story.

No, more precisely, all the main characters are holding smoking guns.

In this way, the outbreak of World War I was a tragedy, not a crime.

The crisis began with suicide bombers and motorcades.

Behind the Sarajevo bombings was a self-proclaimed terrorist organization that praised sacrifice, death, and revenge.

However, this organization was an extraterritorial organization with no clear geographical or political location.

Scattered across the Balkan Peninsula in the form of cell organizations that transcended political boundaries, were unaccountable for their actions, had no apparent ties to any sovereign government, and were clearly extremely difficult to detect outside the organization.

In some ways, one could say that the July 1914 crisis is closer to us today, and appears more vivid, than it did in the 1980s.

Since the end of the Cold War, the stable global bipolar system has given way to a multitude of more complex and unpredictable powers, with empires declining and new powers rising (a global situation that is worth comparing to Europe in 1914).

This shift in perspective prompts a rethinking of the story of how Europe came to war.

Taking on this challenge does not mean embracing a shallow presentism that reconstructs the past to suit the tastes of the present.

Rather, it is an acknowledgement that there are features of the past that can be seen more clearly from our changed perspective.

--- From the introduction

This book is divided into three parts.

Part 1 focuses on Serbia and Austria-Hungary, whose feud ignited war, and follows their interactions up to the eve of the Sarajevo assassination.

Part 2 breaks the narrative and asks four questions in four chapters:

How did Europe become polarized into two opposing camps? How did European states formulate their foreign policies? How did the Balkans—a peripheral region far from Europe's centers of power and wealth—become the setting for such a profound crisis? How did the international system, seemingly entering an era of détente, spiral into all-out war? Part 3 offers a narrative account of the July Crisis itself, beginning with the assassination in Sarajevo and examining the interactions between key decision-making centers, illuminating the calculations, misunderstandings, and decisions that escalated the crisis.

The central argument of this book is that the events of July 1914 can only be properly understood by uncovering the paths taken by key decision-makers.

To achieve this, we need to go beyond simply revisiting the series of international "crises" that preceded the war and understand how these events were experienced, how they were woven into the narratives that structured perception, and how they drove action.

Why did those who made the decisions that led Europe to war act the way they did and perceive the situation the way they did? How did the individual fears and forebodings found in numerous sources connect to the often arrogant and bombastic attitudes of these same individuals? Why were pre-war exoticisms like the Albanian question and the "Bulgarian loan" so significant, and how were they perceived by those in power? When decision-makers discussed the international situation and external threats, were they seeing something substantive, or were they projecting their own fears and desires onto the enemy? Or was it both? My goal is to reconstruct, as vividly as possible, the highly dynamic "decision-making positions" occupied by key actors before and during the summer of 1914.

--- From the introduction

The king or emperor was the only point where the separate chains of command converged.

If the monarch failed to perform the unifying function, for example, if he failed to remedy the constitution's shortcomings, the system ran the risk of being unable to make decisions or making inconsistent decisions.

And continental monarchs often failed to fulfill this role.

No, to be more precise, he refused to perform such a role from the beginning.

This is because he tried to maintain initiative and superiority within the system by dealing separately with key executive officials.

And this attitude ultimately had a negative impact on the policy-making process.

In an environment where decisions made by a minister can be overturned or undermined by colleagues or competitors, ministers often struggle to judge “how their activities fit into the bigger picture.”

The resulting general confusion encouraged ministers, bureaucrats, military commanders, and policy experts to believe that they could assert their own opinions but were not held accountable for the consequences of their policies.

At the same time, the pressure to curry favor with the monarch fostered an atmosphere of competition and flattery, hindering interdepartmental consultation for more balanced decision-making.

The result was a culture of factionalism and rhetoric that would bear dangerous fruit in July 1914.

---From "The Many Voices of European Foreign Policy"

Even if we assume that the prewar European powers had a cohesive executive body that pursued unified and consistent goals, conceived and managed their foreign policies, reconstructing their relationships is a daunting task.

Because the relationship between any two great powers cannot be fully understood without considering their relationships with all the other great powers.

However, the reality in Europe between 1903 and 1914 was more complex than the 'international relations' model suggests.

In a system characterized by weak cabinet cohesion, the monarch's unpredictable interventions, ambiguous civil-military relations, and the hostile rivalry of key political figures, combined with the occasional crisis and heightened tensions caused by security concerns and the incitement of a critical mass media, international relations experienced unprecedented levels of uncertainty during this period.

The resulting erratic policies and confusing signals made it difficult for historians and even politicians on the eve of war to interpret the international situation.

It would be a mistake to overemphasize the view that focuses on the international situation.

All complex political executives, even authoritarian ones, experience internal conflict and volatility.

Literature on 20th-century American foreign relations describes at length the power struggles and intrigues within the government.

As Andrew Preston shows in his excellent study of America's involvement in the Vietnam War, Lyndon B.

Johnson and John F.

Although President Kennedy was reluctant to go to war and the State Department generally opposed intervention, the smaller, more nimble National Security Council (NSC), operating outside of Congressional oversight, strongly supported entry into the war, narrowing the president's options for Vietnam until war was virtually inevitable.

But the situation in Europe before World War I was different (and worse) in one important respect.

Even if some internal conflicts arise, the U.S. executive branch is (from a constitutional perspective) a very clear-cut organization with ultimate responsibility for foreign policy decisions clearly in the hands of the president.

Prewar European governments did not do so.

For the British government, there was a persistent question as to whether Foreign Secretary Gray had the right to make promises to foreign governments without consulting the Cabinet or Parliament.

In fact, this doubt was so strong that Gray was unable to clearly state his intentions.

The situation in France was even more unclear.

The balance of power between the Foreign Office, the Cabinet, and the President remained unsettled, and even the adroit and decisive Poincaré faced efforts in the spring of 1914 to exclude him entirely from the policy-making process.

In Austria-Hungary, and to a lesser extent in Russia, the power to shape foreign policy floated around a multi-layered structure of loosely connected political elites, concentrating in different parts of the system depending on who could form the most effective and cohesive bonds.

In such cases, as in Germany, the existence of a 'supreme' sovereign, rather than clarifying the power relations within the system, has rather blurred them.

This is not a matter of reconstructing the reasoning of two superpowers who carefully considered their options, as during, say, the Cuban Missile Crisis, but of understanding the rapid-fire exchanges between executives with low levels of trust and confidence (even among allies) and high levels of hostility and paranoia, often without a clear understanding of each other's intentions.

The inherent volatility of these international relations is exacerbated by the fluidity of power within each executive branch and the tendency for power to shift from one central point of the system to another.

The internal friction and debate within the Foreign Office may have been beneficial in that it allowed for questions and dissent that would have been suppressed in a more rigid policy environment.

But clearly the risks outweighed the benefits.

When hawks dominate the signaling process on both sides of a potential conflict, as happened during the Agadir crisis or after June 28, 1914, crises can escalate quickly and unpredictably.

---From "The Fluidity of Power" among the many voices of European foreign policy

We must make an important distinction.

French or Russian strategists never engaged in plans to launch a war of aggression against their allies.

What we are dealing with now is a scenario, not a plan itself.

Even so, policymakers in both countries seemed surprisingly indifferent to the potential impact their actions would have on Germany.

French policymakers knew how much the balance of military threat had tilted against Germany.

A report from the French General Staff in June 1914 noted with satisfaction that “the military situation has changed to the disadvantage of Germany,” and the British military assessment was not much different.

But because they believed their actions were entirely defensive and intended only to be offensive against the enemy, key policymakers did not seriously consider the possibility that their decisions would reduce Berlin's options.

It was a stark example of what international relations theorists call the "security dilemma," a situation in which actions taken by one state to strengthen its own security "make other states anxious and force them to prepare for the worst."

---From "The Last Chance: Détente and Danger, 1912-1914"

Something roughly similar happens when we reflect on historical events, especially ones as catastrophic as World War I.

Once such events occur, they give us (or seem to give us) the feeling that they were inevitable.

This process takes place on several levels.

We can find this process in the letters, speeches, and memoirs of the key players in World War I.

They were quick to emphasize that there was no alternative, that war was 'inevitable' and therefore unstoppable.

Narratives that speak of inevitability like this appear in many forms.

Some simply shift the blame to other states or actors, others claim that the system itself has a war-prone nature, regardless of the will of individual actors, or even appeal to the impersonal forces of history or fate.

The search for the causes of World War I has dominated the relevant literature for nearly a century, reinforcing this trend.

As the causes discovered by thoroughly searching Europe over the decades before and after the war pile up like weights on a scale, the scale that had been tilted toward probability eventually tilts toward inevitability.

Contingency, choice, and agency disappear from view.

This is partly a question of perspective.

Looking back on the twists and turns of European international relations before 1914 from the distant future of the early 21st century, we cannot help but view it through the lens of later generations.

Denis Diderot described a well-composed painting as “a whole contained in a single perspective,” and to us, the events preceding World War I seem to compose themselves into something resembling such a picture.

Of course, if you try to fix this problem by fixating on contingency or suddenness, you are going down the wrong path.

More than anything, such an attempt merely replaces the problem of multi-decision with the problem of indecision, that is, the problem of war without cause.

While understanding why World War I might not have happened is important in itself, this insight must be balanced with an understanding of how and why the war actually happened.

---From "The Last Chance: Détente and Danger, 1912-1914"

[Germany] Underlying the calculations of key decision makers was a well-established and (as we can see today from looking back) flawed assumption: that Russia was unlikely to intervene.

It is not difficult to find reasons why the risk level was so absurdly misjudged.

One obvious reason was Russia's acceptance of Austria's ultimatum to Serbia in October 1913.

And at that time, as already mentioned, there was a deep-rooted idea that time was on Russia's side.

In Berlin, the Archduke's assassination was seen as an attack on the principles of monarchy, set in a political culture with a strong tendency towards regicide (a view also found in some British newspapers).

Even if Russia had been firmly committed to Pan-Slavism, it was difficult to imagine the Tsar siding with the 'regicides', as the Kaiser repeatedly insisted.

To all this must be added the eternal problem of interpreting the intentions of the Russian executive.

Germany did not realize how much the Austro-Serbian conflict was already part of the strategic thinking of the Franco-Russian alliance.

Germany failed to grasp how indifferent the two Western powers were to the question of who had provoked the conflict.

…Looking at it this way, Germany's strategy was not, strictly speaking, a strategy focused on risk, but rather a strategy aimed at revealing the true extent of the threat posed by Russia.

In other words, if Russia had chosen to mobilize against Germany, thereby triggering a continental war, it would have revealed not the danger posed by German actions, but Russia's strong determination to rebalance the European system through war.

From this somewhat pessimistic perspective, Germany was not taking a risk, but rather testing a threat.

This was the logic behind Bethmann's frequent references to the Russian threat in the months leading up to the outbreak of war.

---From "Spreading Ripples"

The outbreak of war in 1914 is not an Agatha Christie-style drama that ends with the murderer being found in a greenhouse, holding a smoking pistol and watching over a corpse.

There are no smoking guns in this story.

No, more precisely, all the main characters are holding smoking guns.

In this way, the outbreak of World War I was a tragedy, not a crime.

--- From the conclusion

Publisher's Review

In December 2017, UN Under-Secretary-General Feltman asked why

Did you give this book to North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong-ho?

In December 2017, UN Under-Secretary-General Jeffrey Feltman, who visited North Korea, met with North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong-ho and outlined three demands for "preventing accidental clashes."

The demands included restoring military communication channels that were suspended in 2009 to reduce the risk of accidental war, signaling readiness to talk to the United States, and implementing UN Security Council resolutions on denuclearization.

Feltman also handed over a history book, which was unusual for a diplomatic meeting.

This book is Christopher Clarke's The Sleepwalkers.

Feltman's act of delivering a thick history book written in English, not Korean, that dealt with the causes of the war that broke out in Europe over a century ago to the North Korean foreign minister must have contained a diplomatic message.

What was the message?

- "Masterpiece" - [New York Times] [Wall Street Journal] [Daily Mail]

“A monumental, revelatory, even revolutionary book.” - [Boston Globe]

"The best account of the causes of World War I" - [Guardian] [Washington Post]

- "A New Standard for Authoring" - [Foreign Efforts]

“A beautifully written book that combines meticulous research, nuanced analysis, and elegant prose.” - [The Washington Post]

- Selected as Book of the Year by [The Independent], [The Sunday Times], [The Financial Times], etc.

- [Los Angeles Times] Book Award, Laura Shannon Award Winner

In 2014, the West celebrated the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, and a flurry of works shedding new light on pre-war Europe were published.

With so many major books coming out at the same time, including Margaret MacMillan's The War That Ended the Peace, Sean McMeekin's July 1914, and Max Hastings' The Catastrophe of 1914, major media outlets even ran reviews comparing a few of them.

In this competitive arena, The Sleepwalkers has been hailed by prominent scholars such as Ian Kershaw and Niall Ferguson as a first-rate narrative and a new standard work that redefines our understanding of the origins of World War I.

It was selected as a book of the year by [The New York Times], [The Independent], [The Financial Times], etc., and won the Laura Shannon Award for outstanding European research (2015).

It has also been greatly loved by readers and has now established itself as a must-read, following Barbara Tuchman's The Guns of August.

The July Crisis, the subject of this book and the period just before the outbreak of World War I, is considered one of the most complex crises in history, a crisis that even dwarfs the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The literature dealing with the origins or causes of this war alone is so vast that it could be called an industry.

For this reason, “virtually no view on the origins of this war can be supported by a select body of data” (p. 27). The author, well aware of this, chooses an approach that follows the decisions of the key actors who brought about the war chronologically, rather than focusing on a specific cause and presenting yet another hypothesis or viewpoint.

In other words, we closely trace the chain of interactions between them.

This book is divided into three parts.

Part 1 focuses on Serbia and Austria-Hungary, whose feud ignited war, and follows their interactions up to the eve of the Sarajevo assassination.

Part 2 breaks the narrative and asks four questions in four chapters:

① How did Europe become polarized into two hostile camps? ② How did European states formulate their foreign policies? ③ How did the Balkans—a peripheral region far from Europe's centers of power and wealth—become the setting for such a profound crisis? ④ How did the international system, seemingly entering an era of détente, spiral into all-out war? Part 3 provides a narrative of the July Crisis itself, beginning with the assassination in Sarajevo and examining the interactions between key decision-making centers, illuminating the calculations, misunderstandings, and decisions that escalated the crisis.

Not “why” it broke out, but “how” it happened.

- Beyond the responsibility for World War I

Until now, discussions about the causes of World War I have primarily focused on 'why' the war broke out.

This is likely to lead to a debate about who is responsible for the disaster that took the lives of 20 million people.

This blaming began before the war and continued through the 1919 Treaty of Versailles' "war responsibility" clause (which held Germany and its allies responsible for starting the war) and the resulting massive reparations, and the 1960s German historian Fritz Fischer's "Fischer Thesis" (the view that Kaiser Wilhelm II and his ministers planned and ultimately carried out the war in advance to break Germany's isolation in Europe, suppress domestic discontent, and above all, to establish itself as a world power).

In contrast, recent works, including this one, generally emphasize the shared responsibility of European countries.

In particular, the author persuasively demonstrates, through detailed accounts, that the view that blames a single country for the war or ranks the belligerents by their "blame" while ignoring multilateral interactions is not consistent with the evidence.

Anyone who has read this book will agree that France and Russia (let alone Britain) are at least as responsible as Germany and Austria-Hungary.

From this perspective, the war of 1914 was a product of the political culture shared by European nations, a common tragedy rather than a crime committed by a particular nation.

The key decision makers of 1914 were not puppets of structures and systems.

He was a protagonist full of action skills.

The central argument of this book is that the events of July 1914 can only be properly understood by uncovering the paths taken by key decision-makers.

To achieve this, we need to go beyond simply revisiting the series of international "crises" that preceded the war and understand how these events were experienced, how they were woven into the narratives that structured perception, and how they drove action.

The author focuses on the question of 'how' the war happened rather than 'why' it happened, in an attempt to understand the decisions of the decision makers from their own perspective as much as possible.

Why did those who made the decisions that led Europe to war act the way they did and perceive the situation the way they did? How did the individual fears and forebodings found in numerous sources connect to the often arrogant and bombastic attitudes of these same individuals? Why were pre-war exoticisms like the Albanian issue and the "Bulgarian loan" so significant, and how were they perceived by those in power? When decision-makers discussed the international situation and external threats, were they seeing something substantive, or were they projecting their own fears and desires onto the enemy? Or was it both? The author guides readers to answer these questions by vividly reconstructing the highly dynamic "decision-making positions" occupied by key actors before and during the summer of 1914.

The author does not make the mistake of assuming that their future is closed.

Rather, he emphasizes that they had a variety of choices open to them, and that each of them held the seeds of a future different from their actual history.

They were not mere accomplices in the impersonal forward movement of history, puppets moved by the logic of the system, but protagonists, full of agency and capable of realizing a sufficiently different future.

War was not an inevitable outcome, but the culmination of a chain of decisions they made.

Of course, we should not focus only on contingency.

The key point the author intends is 'balance'.

“Understanding why World War I might not have happened is important in itself, but this insight must be balanced by an understanding of how and why the war actually happened.” (p. 563)

Reading the 21st-Century World from 1914 Europe

- Why we need to look into the history of wars from 100 years ago

Regarding Feltman's aforementioned book gift, Washington Post columnist David Ignatius analyzed that Feltman gave the book to maximize the message about the risk of unintended conflict.

For Feltman, this book would have been a perfect wake-up call to the dangers of "unintended conflict."

Before World War I, Europe was a world where any country could say it had "defensive" intentions and the other side had "offensive" intentions.

Although there were some hawks who consistently advocated war, no country in the executive branch as a whole actively planned for war.

Yet, the level of trust and confidence (even among allies) was low, and the level of hostility and paranoia was high, as executives interacted at a rapid-fire pace without fully understanding each other's intentions, resulting in the worst catastrophe ever.

Key decision-makers were so consumed by their own national interests that they never foresaw the consequences of their efforts.

In short, “the protagonists of 1914 were sleepwalkers, blinded by their wide-open eyes, caught in a dream, unaware of the horror they were about to unleash upon the world.” (p. 859)

The world situation in the 21st century is very similar to that of Europe a hundred years ago.

Since the end of the Cold War, the stable global bipolar system has given way to a complex and unpredictable array of powers, with empires declining and new powers rising.

This shift in perspective prompts a rethinking of the story of how Europe came to war.

Taking on this challenge does not mean embracing a shallow presentism that reconstructs the past to suit the tastes of the present.

Rather, it is an acknowledgement that there are features of the past that can be seen more clearly from our changed perspective.

Readers who follow the course of the crisis in the summer of 1914 will undoubtedly recognize its vivid modernity.

The story in this book will provide crucial insights, especially for Korean readers who have lived with the possibility of accidental conflict.

We can still find key decision makers today who are similar in character to the protagonists of this book.

I hope this book will help them, and us, wake up from our modern 'sleepwalking'.

Did you give this book to North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong-ho?

In December 2017, UN Under-Secretary-General Jeffrey Feltman, who visited North Korea, met with North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong-ho and outlined three demands for "preventing accidental clashes."

The demands included restoring military communication channels that were suspended in 2009 to reduce the risk of accidental war, signaling readiness to talk to the United States, and implementing UN Security Council resolutions on denuclearization.

Feltman also handed over a history book, which was unusual for a diplomatic meeting.

This book is Christopher Clarke's The Sleepwalkers.

Feltman's act of delivering a thick history book written in English, not Korean, that dealt with the causes of the war that broke out in Europe over a century ago to the North Korean foreign minister must have contained a diplomatic message.

What was the message?

- "Masterpiece" - [New York Times] [Wall Street Journal] [Daily Mail]

“A monumental, revelatory, even revolutionary book.” - [Boston Globe]

"The best account of the causes of World War I" - [Guardian] [Washington Post]

- "A New Standard for Authoring" - [Foreign Efforts]

“A beautifully written book that combines meticulous research, nuanced analysis, and elegant prose.” - [The Washington Post]

- Selected as Book of the Year by [The Independent], [The Sunday Times], [The Financial Times], etc.

- [Los Angeles Times] Book Award, Laura Shannon Award Winner

In 2014, the West celebrated the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, and a flurry of works shedding new light on pre-war Europe were published.

With so many major books coming out at the same time, including Margaret MacMillan's The War That Ended the Peace, Sean McMeekin's July 1914, and Max Hastings' The Catastrophe of 1914, major media outlets even ran reviews comparing a few of them.

In this competitive arena, The Sleepwalkers has been hailed by prominent scholars such as Ian Kershaw and Niall Ferguson as a first-rate narrative and a new standard work that redefines our understanding of the origins of World War I.

It was selected as a book of the year by [The New York Times], [The Independent], [The Financial Times], etc., and won the Laura Shannon Award for outstanding European research (2015).

It has also been greatly loved by readers and has now established itself as a must-read, following Barbara Tuchman's The Guns of August.

The July Crisis, the subject of this book and the period just before the outbreak of World War I, is considered one of the most complex crises in history, a crisis that even dwarfs the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The literature dealing with the origins or causes of this war alone is so vast that it could be called an industry.

For this reason, “virtually no view on the origins of this war can be supported by a select body of data” (p. 27). The author, well aware of this, chooses an approach that follows the decisions of the key actors who brought about the war chronologically, rather than focusing on a specific cause and presenting yet another hypothesis or viewpoint.

In other words, we closely trace the chain of interactions between them.

This book is divided into three parts.

Part 1 focuses on Serbia and Austria-Hungary, whose feud ignited war, and follows their interactions up to the eve of the Sarajevo assassination.

Part 2 breaks the narrative and asks four questions in four chapters:

① How did Europe become polarized into two hostile camps? ② How did European states formulate their foreign policies? ③ How did the Balkans—a peripheral region far from Europe's centers of power and wealth—become the setting for such a profound crisis? ④ How did the international system, seemingly entering an era of détente, spiral into all-out war? Part 3 provides a narrative of the July Crisis itself, beginning with the assassination in Sarajevo and examining the interactions between key decision-making centers, illuminating the calculations, misunderstandings, and decisions that escalated the crisis.

Not “why” it broke out, but “how” it happened.

- Beyond the responsibility for World War I

Until now, discussions about the causes of World War I have primarily focused on 'why' the war broke out.

This is likely to lead to a debate about who is responsible for the disaster that took the lives of 20 million people.

This blaming began before the war and continued through the 1919 Treaty of Versailles' "war responsibility" clause (which held Germany and its allies responsible for starting the war) and the resulting massive reparations, and the 1960s German historian Fritz Fischer's "Fischer Thesis" (the view that Kaiser Wilhelm II and his ministers planned and ultimately carried out the war in advance to break Germany's isolation in Europe, suppress domestic discontent, and above all, to establish itself as a world power).

In contrast, recent works, including this one, generally emphasize the shared responsibility of European countries.

In particular, the author persuasively demonstrates, through detailed accounts, that the view that blames a single country for the war or ranks the belligerents by their "blame" while ignoring multilateral interactions is not consistent with the evidence.

Anyone who has read this book will agree that France and Russia (let alone Britain) are at least as responsible as Germany and Austria-Hungary.

From this perspective, the war of 1914 was a product of the political culture shared by European nations, a common tragedy rather than a crime committed by a particular nation.

The key decision makers of 1914 were not puppets of structures and systems.

He was a protagonist full of action skills.

The central argument of this book is that the events of July 1914 can only be properly understood by uncovering the paths taken by key decision-makers.

To achieve this, we need to go beyond simply revisiting the series of international "crises" that preceded the war and understand how these events were experienced, how they were woven into the narratives that structured perception, and how they drove action.

The author focuses on the question of 'how' the war happened rather than 'why' it happened, in an attempt to understand the decisions of the decision makers from their own perspective as much as possible.

Why did those who made the decisions that led Europe to war act the way they did and perceive the situation the way they did? How did the individual fears and forebodings found in numerous sources connect to the often arrogant and bombastic attitudes of these same individuals? Why were pre-war exoticisms like the Albanian issue and the "Bulgarian loan" so significant, and how were they perceived by those in power? When decision-makers discussed the international situation and external threats, were they seeing something substantive, or were they projecting their own fears and desires onto the enemy? Or was it both? The author guides readers to answer these questions by vividly reconstructing the highly dynamic "decision-making positions" occupied by key actors before and during the summer of 1914.

The author does not make the mistake of assuming that their future is closed.

Rather, he emphasizes that they had a variety of choices open to them, and that each of them held the seeds of a future different from their actual history.

They were not mere accomplices in the impersonal forward movement of history, puppets moved by the logic of the system, but protagonists, full of agency and capable of realizing a sufficiently different future.

War was not an inevitable outcome, but the culmination of a chain of decisions they made.

Of course, we should not focus only on contingency.

The key point the author intends is 'balance'.

“Understanding why World War I might not have happened is important in itself, but this insight must be balanced by an understanding of how and why the war actually happened.” (p. 563)

Reading the 21st-Century World from 1914 Europe

- Why we need to look into the history of wars from 100 years ago

Regarding Feltman's aforementioned book gift, Washington Post columnist David Ignatius analyzed that Feltman gave the book to maximize the message about the risk of unintended conflict.

For Feltman, this book would have been a perfect wake-up call to the dangers of "unintended conflict."

Before World War I, Europe was a world where any country could say it had "defensive" intentions and the other side had "offensive" intentions.

Although there were some hawks who consistently advocated war, no country in the executive branch as a whole actively planned for war.

Yet, the level of trust and confidence (even among allies) was low, and the level of hostility and paranoia was high, as executives interacted at a rapid-fire pace without fully understanding each other's intentions, resulting in the worst catastrophe ever.

Key decision-makers were so consumed by their own national interests that they never foresaw the consequences of their efforts.

In short, “the protagonists of 1914 were sleepwalkers, blinded by their wide-open eyes, caught in a dream, unaware of the horror they were about to unleash upon the world.” (p. 859)

The world situation in the 21st century is very similar to that of Europe a hundred years ago.

Since the end of the Cold War, the stable global bipolar system has given way to a complex and unpredictable array of powers, with empires declining and new powers rising.

This shift in perspective prompts a rethinking of the story of how Europe came to war.

Taking on this challenge does not mean embracing a shallow presentism that reconstructs the past to suit the tastes of the present.

Rather, it is an acknowledgement that there are features of the past that can be seen more clearly from our changed perspective.

Readers who follow the course of the crisis in the summer of 1914 will undoubtedly recognize its vivid modernity.

The story in this book will provide crucial insights, especially for Korean readers who have lived with the possibility of accidental conflict.

We can still find key decision makers today who are similar in character to the protagonists of this book.

I hope this book will help them, and us, wake up from our modern 'sleepwalking'.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: January 28, 2019

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 1,016 pages | 1,406g | 145*210*60mm

- ISBN13: 9791188990245

- ISBN10: 1188990241

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)