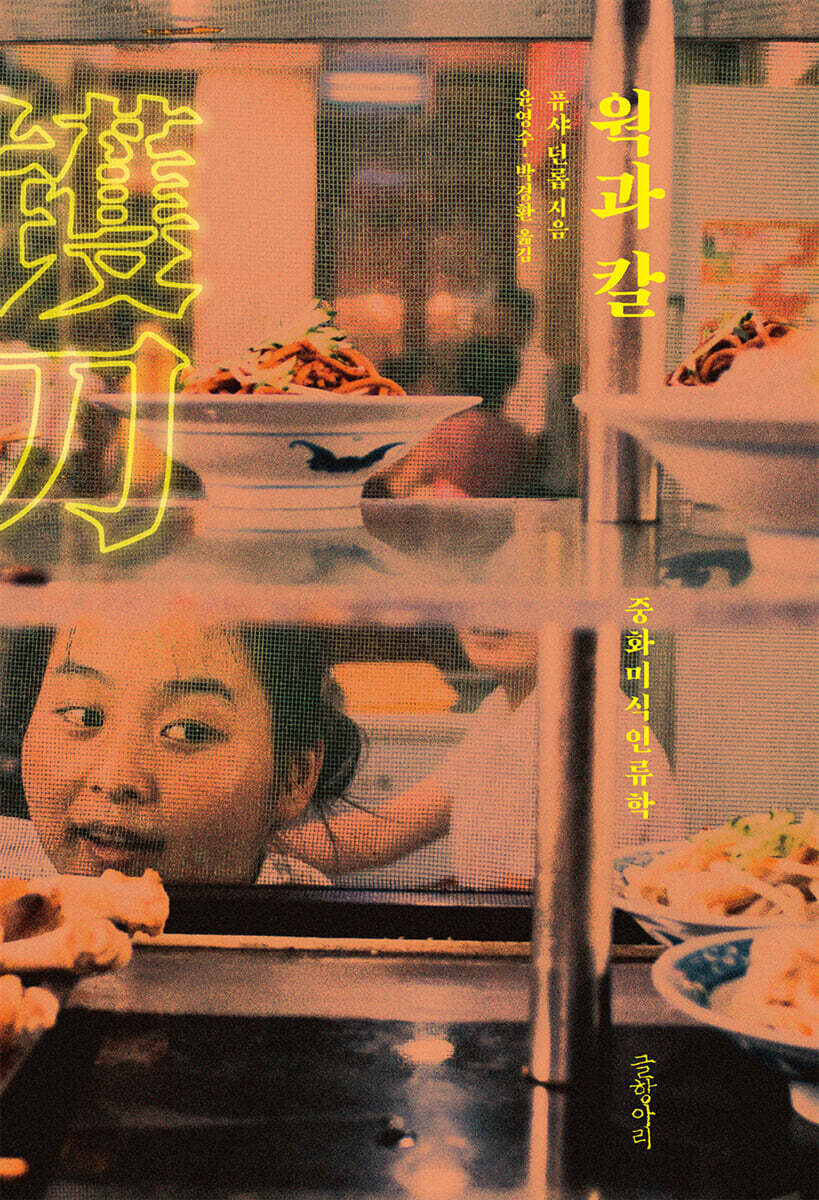

wok and knife

|

Description

Book Introduction

About the oldest global cuisine

A belated and true tribute

An authentic humanities book on Chinese cuisine!

Taste, taste, and taste again.

Feeling the flavors of different regions.

Experience the endless variations of Chinese cuisine.

There are countless theories, descriptions, legends and recipes.

How it actually works in the field, in the mouth, on the tongue

I experienced it.

Martial artists and musicians practice

Just like building skills

Even professional gourmets learn through experience.

_ In the text

China is a large country, but when it comes to cuisine, it feels vast beyond words.

China is a country made up of 22 provinces and about 660 cities.

Not only are regional cuisines characterized by strong regional characteristics stemming from differences in ingredients and lifestyles, but the variations they create are incredibly complex.

So, asking someone to think of one dish that represents China is quite cruel.

Because no matter what you choose, there's a good chance that not many people will nod their heads to it.

Chinese cuisine was the first truly global cuisine.

As the first Chinese workers began to migrate and settle abroad, restaurants followed.

Yet, while Chinese cuisine is one of the world's most beloved culinary traditions, it's also one of the least understood.

The overwhelming prevalence of simplified Cantonese cuisine for over a century has largely left foreigners with little exposure to the richness and delicacy of Chinese food.

But now that trend is changing.

In "The Wok and the Knife," Fusha Dunlop delves into the history, philosophy, and cooking techniques of Chinese food culture.

The author is one of the most renowned authors in the field, having already published several books on Chinese cuisine, and has detailed his relationship with Chinese food in his books.

Dunlop, who moved to China as a student in the 1990s, put his studies on the back burner and spent all day eating.

Then, I just kept eating and eating until I eventually became the first non-Chinese student to enroll in Sichuan Culinary Institute.

After many twists and turns, I became a food journalist and published several books.

But it would be a mistake to consider The Wok and the Knife as just one of Fuchsia Dunlop's many food books.

This book is a masterpiece that comprehensively encapsulates the author's accumulated knowledge of Chinese gastronomy anthropology, and, like an encyclopedia, beautifully contextualizes information on countless regions, ingredients, recipes, history, and philosophy.

Each chapter features around 30 classic dishes, including mapo tofu, dongpo pork, dosakmyeon, and yuzu rind stew. However, as the chapter moves on to discussing stews, sauces, and broths, it delves into 3,000 years of history, delves into the origins of the dishes, and explains the process of their evolution.

It reveals unique aspects of Chinese cuisine, such as the importance of soybeans, the allure of exotic ingredients, and the history of Buddhist vegetarianism.

Traveling across China, meeting food producers, chefs, gourmets, and home cooks, Fuchsia Dunlop takes readers on an unforgettable journey that explores how food is made, consumed, and handled in mainland China.

Weaving together historical narratives, mouth-watering culinary descriptions, and 30 years of field research, this book is a vivid and monumental tribute to the joys and wonders of Chinese cuisine.

The virtue of this book is not simply that it lists novel Chinese dishes encyclopedically, but that it systematically researches and presents several archetypes that run through Chinese cuisine.

Formation of basic cooking method of chopping with a knife and steaming or stir-frying.

The north is wheat and the south is rice, a large border.

The influence of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and Islamic culture on diet, the history of Buddhist vegetarian cuisine, the culinary culture of seasoning that combines the five flavors in a splendid way and the culture of preserving the natural flavors of ingredients, and the deep-rooted idea of managing health through the harmony of everyday food.

Exploring the reasons why the Chinese always cut meat into small pieces and cook it instead of throwing it into the fire in large chunks.

Through this book, we learn that during the time of Confucius, the main food source in northern China was millet, not rice.

Likewise, we learn that for hundreds of years before the invention of the gas stove, which made wok cooking possible, Chinese aristocrats enjoyed banquets centered around jing soup.

Geong is what we would call a thick starch stew in Western terms, but it is made with a much wider variety of ingredients, each with a subtly different flavor.

We also learn that even before the Song Dynasty, soy sauce was not eaten in China, but instead dozens of different types of fermented sauces were used to flavor food, and that soy sauce was originally an unintended byproduct that somehow became popular.

As I read these stories, I find myself picturing the true nature of the giant elephant that is Chinese cuisine.

A belated and true tribute

An authentic humanities book on Chinese cuisine!

Taste, taste, and taste again.

Feeling the flavors of different regions.

Experience the endless variations of Chinese cuisine.

There are countless theories, descriptions, legends and recipes.

How it actually works in the field, in the mouth, on the tongue

I experienced it.

Martial artists and musicians practice

Just like building skills

Even professional gourmets learn through experience.

_ In the text

China is a large country, but when it comes to cuisine, it feels vast beyond words.

China is a country made up of 22 provinces and about 660 cities.

Not only are regional cuisines characterized by strong regional characteristics stemming from differences in ingredients and lifestyles, but the variations they create are incredibly complex.

So, asking someone to think of one dish that represents China is quite cruel.

Because no matter what you choose, there's a good chance that not many people will nod their heads to it.

Chinese cuisine was the first truly global cuisine.

As the first Chinese workers began to migrate and settle abroad, restaurants followed.

Yet, while Chinese cuisine is one of the world's most beloved culinary traditions, it's also one of the least understood.

The overwhelming prevalence of simplified Cantonese cuisine for over a century has largely left foreigners with little exposure to the richness and delicacy of Chinese food.

But now that trend is changing.

In "The Wok and the Knife," Fusha Dunlop delves into the history, philosophy, and cooking techniques of Chinese food culture.

The author is one of the most renowned authors in the field, having already published several books on Chinese cuisine, and has detailed his relationship with Chinese food in his books.

Dunlop, who moved to China as a student in the 1990s, put his studies on the back burner and spent all day eating.

Then, I just kept eating and eating until I eventually became the first non-Chinese student to enroll in Sichuan Culinary Institute.

After many twists and turns, I became a food journalist and published several books.

But it would be a mistake to consider The Wok and the Knife as just one of Fuchsia Dunlop's many food books.

This book is a masterpiece that comprehensively encapsulates the author's accumulated knowledge of Chinese gastronomy anthropology, and, like an encyclopedia, beautifully contextualizes information on countless regions, ingredients, recipes, history, and philosophy.

Each chapter features around 30 classic dishes, including mapo tofu, dongpo pork, dosakmyeon, and yuzu rind stew. However, as the chapter moves on to discussing stews, sauces, and broths, it delves into 3,000 years of history, delves into the origins of the dishes, and explains the process of their evolution.

It reveals unique aspects of Chinese cuisine, such as the importance of soybeans, the allure of exotic ingredients, and the history of Buddhist vegetarianism.

Traveling across China, meeting food producers, chefs, gourmets, and home cooks, Fuchsia Dunlop takes readers on an unforgettable journey that explores how food is made, consumed, and handled in mainland China.

Weaving together historical narratives, mouth-watering culinary descriptions, and 30 years of field research, this book is a vivid and monumental tribute to the joys and wonders of Chinese cuisine.

The virtue of this book is not simply that it lists novel Chinese dishes encyclopedically, but that it systematically researches and presents several archetypes that run through Chinese cuisine.

Formation of basic cooking method of chopping with a knife and steaming or stir-frying.

The north is wheat and the south is rice, a large border.

The influence of Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, and Islamic culture on diet, the history of Buddhist vegetarian cuisine, the culinary culture of seasoning that combines the five flavors in a splendid way and the culture of preserving the natural flavors of ingredients, and the deep-rooted idea of managing health through the harmony of everyday food.

Exploring the reasons why the Chinese always cut meat into small pieces and cook it instead of throwing it into the fire in large chunks.

Through this book, we learn that during the time of Confucius, the main food source in northern China was millet, not rice.

Likewise, we learn that for hundreds of years before the invention of the gas stove, which made wok cooking possible, Chinese aristocrats enjoyed banquets centered around jing soup.

Geong is what we would call a thick starch stew in Western terms, but it is made with a much wider variety of ingredients, each with a subtly different flavor.

We also learn that even before the Song Dynasty, soy sauce was not eaten in China, but instead dozens of different types of fermented sauces were used to flavor food, and that soy sauce was originally an unintended byproduct that somehow became popular.

As I read these stories, I find myself picturing the true nature of the giant elephant that is Chinese cuisine.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

China map

[Prologue] Introducing Chinese Cuisine Abroad: Sweet and Sour Pork Balls

Fire: The Origin of Chinese Cuisine

Civilization began with roasting: Char Siu Pork with Honey Soup

Xiaomi and Dami, the centerpieces of the dining table: White rice

Finely chop and simmer: Song Buin's Fish Soup

A nutritious dish that has permeated our daily lives: Yeoju Pork Rib Soup

Farm Heaven and Earth: Choosing Ingredients

Local seasonal ingredients: Anji bamboo shoots and Jinhwa ham

The illusion that vegetables are supporting roles: Stir-fried ginger and mustard greens

Gangnam Suhyang's Ingredients: Sunchae Sea Bass Stew??

Amazing Treasure Chest Beans: Mapo Tofu

Pork, the meat of meats: Dongpo Pork

Chinese Cuisine: A Multicultural Melting Pot: Shuyangrou?

The Magic of Fermented Food: Drunken Crab

Infinite Challenge of Ingredients: Steamed Yuzu Peel with Shrimp Roe

Texture is as important as taste: Catfish that enjoys honor, Tobo Noryem?

Culinary Extremes, Exotic Ingredients: Surpassing Bear's Paw

Kitchen?: The Art of Cooking

Broth Culture Hidden by MSG: Yipinguo

The ever-changing combination of the five flavors: Tangsuyuk Huanghe Carp in Sweet and Sour Sauce

Chinese Chef's Knife Skills: Shunde's Sashimi

It all started with steaming: steamed fish

Just a moment: Shrimp Stir-fry Cheong?Da-Yu

Cooking term: braised tofu

Everything Made with Dough: Knife-Cut Noodles

The Birth of Dim Sum: Xiaolongbao

Table food?: Food and thoughts

Are there desserts in Chinese cuisine? : Mother Duck Dumplings

The distinction between the four major cuisines and the eight major cuisines: Chongqing chicken in a pile of chili peppers?

Deep-rooted Vegetarian Tradition: Stir-fried Dried Eel

Organic from the Peach Blossom Land: Stir-fried Sweet Potato Stems

Sinicized Western Food: Russian Soup

A dish that shares the heart: A loving mother's braised pork

[Epilogue] Past and Future: Chop Sui

A partial and highly subjective chronicle of Chinese food culture

Acknowledgements

Americas

Translator's Note

Search

[Prologue] Introducing Chinese Cuisine Abroad: Sweet and Sour Pork Balls

Fire: The Origin of Chinese Cuisine

Civilization began with roasting: Char Siu Pork with Honey Soup

Xiaomi and Dami, the centerpieces of the dining table: White rice

Finely chop and simmer: Song Buin's Fish Soup

A nutritious dish that has permeated our daily lives: Yeoju Pork Rib Soup

Farm Heaven and Earth: Choosing Ingredients

Local seasonal ingredients: Anji bamboo shoots and Jinhwa ham

The illusion that vegetables are supporting roles: Stir-fried ginger and mustard greens

Gangnam Suhyang's Ingredients: Sunchae Sea Bass Stew??

Amazing Treasure Chest Beans: Mapo Tofu

Pork, the meat of meats: Dongpo Pork

Chinese Cuisine: A Multicultural Melting Pot: Shuyangrou?

The Magic of Fermented Food: Drunken Crab

Infinite Challenge of Ingredients: Steamed Yuzu Peel with Shrimp Roe

Texture is as important as taste: Catfish that enjoys honor, Tobo Noryem?

Culinary Extremes, Exotic Ingredients: Surpassing Bear's Paw

Kitchen?: The Art of Cooking

Broth Culture Hidden by MSG: Yipinguo

The ever-changing combination of the five flavors: Tangsuyuk Huanghe Carp in Sweet and Sour Sauce

Chinese Chef's Knife Skills: Shunde's Sashimi

It all started with steaming: steamed fish

Just a moment: Shrimp Stir-fry Cheong?Da-Yu

Cooking term: braised tofu

Everything Made with Dough: Knife-Cut Noodles

The Birth of Dim Sum: Xiaolongbao

Table food?: Food and thoughts

Are there desserts in Chinese cuisine? : Mother Duck Dumplings

The distinction between the four major cuisines and the eight major cuisines: Chongqing chicken in a pile of chili peppers?

Deep-rooted Vegetarian Tradition: Stir-fried Dried Eel

Organic from the Peach Blossom Land: Stir-fried Sweet Potato Stems

Sinicized Western Food: Russian Soup

A dish that shares the heart: A loving mother's braised pork

[Epilogue] Past and Future: Chop Sui

A partial and highly subjective chronicle of Chinese food culture

Acknowledgements

Americas

Translator's Note

Search

Detailed image

Publisher's Review

Korean Jjajangmyeon, British Tangsu Meatballs

The translators of this book say:

If you were asked to pick the national food of Korea, Jjajangmyeon would be in the top five.

This dish is clearly Chinese, but it is not well known in mainland China outside of Shandong and Beijing, and it has only been in Korea for about a century.

There are many reasons why Jjajangmyeon has captured the taste buds of Koreans.

Above all, Shandong cuisine was boldly modified several times to suit our tastes, and due to excessive regulations, the restaurant industry became the only means of livelihood for overseas Chinese, spreading throughout the country.

There was a time when it was classified as a price-controlled item and had to become synonymous with common people's food, and Chinese restaurants also took the lead in delivery culture, dramatically increasing accessibility.

These days, mala tang is taking over that spot.

All food cultures evolve, but Chinese cuisine's adaptability is truly remarkable.

In the 1980s in England, when author Fuchsia Dunlop was growing up, tangsuyuk (more precisely, tangsu meatballs) was said to have a similar status to Korea's jajangmyeon.

In the United States, chop suey and zao zhong tang jie are synonymous with Chinese food and are universally loved, while in Japan, ramen and fried dumplings are the same.

Behind countless localized Chinese dishes around the world, there's a backstory just as long as Korea's Jajangmyeon.

What they have in common is that they are dishes that arose from contact between different cultures.

It's not just Chinese cuisine overseas that's like this.

The reason why Chinese cuisine is so diverse within China is not only because the landmass is so vast, with climates and soils varying greatly from region to region, but also because there has been an unusually high level of contact between different cultures.

In her book, Fusha Dunlop tells of the Han Dynasty, where noodles and noodle dishes were born after the introduction of millstones from Central Asia, and of the cosmopolitan culture of the Tang Dynasty, when exchanges with the West were at their peak, which explains why Muslim restaurants still exist in every major Chinese city.

He says that the 13th century Song Dynasty, when the capital was moved from Kaifeng in the north to Hangzhou in the south due to the Mongol invasion and the northern and southern cultures were beautifully fused, was the golden age of Chinese food culture that makes you want to go back in time. He also mentions that the Qing Emperor Qianlong was fascinated by Jiangnan cuisine and actively incorporated it into the Manchu court cuisine.

There are also stories of exotic Chinese cuisines, such as the aforementioned Jjajangmyeon, that were adapted to local cultures by overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, the United States, and Europe, and the improved style of "Xichan" that emerged a century ago when Shanghai was the "Paris of Asia" and is still alive today.

Food that touches, conflicts, and embraces

When different cultures come into unexpected contact and ultimately embrace each other, something wonderful is born.

At first, they may feel unfamiliar and experience conflict due to each other's stereotypes, but eventually they will realize that there is a point where compromise is possible, and then something unexpected and third will emerge.

For example, Fusha Dunlop speculates that although the Central Plains Chinese did not accept the dairy products consumed by the northern 'barbarians', they probably copied the process by which they made milk into cheese, solidifying the soybean water ground on a millstone to create tofu.

Doesn't every culture evolve through a process of contact, conflict, and inclusion?

Conversely, a culture that has no contact with the outside world and fears diversity stagnates or degenerates.

That is why the Korean subtitle of this book is ‘Chinese Gastronomic Anthropology.’

Author Fusha Dunlop became fascinated with Chinese cuisine while attending a local cooking school in Chengdu, Sichuan, during a year-long stay in the mid-1990s.

And I spent over ten years studying and exploring cuisines from all over China.

The 2008 book, Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper, which summarized the adventures, also became a hot topic in China's expat community at the time.

Before and after that, he published several bestselling recipe books covering Sichuan, Hunan, and Jiangnan cuisines, and he also constantly organized gourmet tours to introduce Chinese cuisine to Westerners.

The translators say:

The 1990s and 2000s were a time when the fruits of China's reform and opening-up policy were reaching their peak.

As China's economy grew at a breakneck pace and its doors opened wide to attract investment, countless foreigners flocked to the country.

Looking back, China at that time was a place where different cultures clashed noisily.

There were many misunderstandings and conflicts, but unlike today, it was a time when efforts to get along and accept each other were the prerequisite.

I think that the fact that Fusha Dunlop was able to freely explore the food cultures of all of China was largely due to the open atmosphere of the time, in addition to the fact that she was a Westerner.

This book is the culmination of the author's 30 years of dedication to Chinese food.

The translators of this book say:

If you were asked to pick the national food of Korea, Jjajangmyeon would be in the top five.

This dish is clearly Chinese, but it is not well known in mainland China outside of Shandong and Beijing, and it has only been in Korea for about a century.

There are many reasons why Jjajangmyeon has captured the taste buds of Koreans.

Above all, Shandong cuisine was boldly modified several times to suit our tastes, and due to excessive regulations, the restaurant industry became the only means of livelihood for overseas Chinese, spreading throughout the country.

There was a time when it was classified as a price-controlled item and had to become synonymous with common people's food, and Chinese restaurants also took the lead in delivery culture, dramatically increasing accessibility.

These days, mala tang is taking over that spot.

All food cultures evolve, but Chinese cuisine's adaptability is truly remarkable.

In the 1980s in England, when author Fuchsia Dunlop was growing up, tangsuyuk (more precisely, tangsu meatballs) was said to have a similar status to Korea's jajangmyeon.

In the United States, chop suey and zao zhong tang jie are synonymous with Chinese food and are universally loved, while in Japan, ramen and fried dumplings are the same.

Behind countless localized Chinese dishes around the world, there's a backstory just as long as Korea's Jajangmyeon.

What they have in common is that they are dishes that arose from contact between different cultures.

It's not just Chinese cuisine overseas that's like this.

The reason why Chinese cuisine is so diverse within China is not only because the landmass is so vast, with climates and soils varying greatly from region to region, but also because there has been an unusually high level of contact between different cultures.

In her book, Fusha Dunlop tells of the Han Dynasty, where noodles and noodle dishes were born after the introduction of millstones from Central Asia, and of the cosmopolitan culture of the Tang Dynasty, when exchanges with the West were at their peak, which explains why Muslim restaurants still exist in every major Chinese city.

He says that the 13th century Song Dynasty, when the capital was moved from Kaifeng in the north to Hangzhou in the south due to the Mongol invasion and the northern and southern cultures were beautifully fused, was the golden age of Chinese food culture that makes you want to go back in time. He also mentions that the Qing Emperor Qianlong was fascinated by Jiangnan cuisine and actively incorporated it into the Manchu court cuisine.

There are also stories of exotic Chinese cuisines, such as the aforementioned Jjajangmyeon, that were adapted to local cultures by overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia, the United States, and Europe, and the improved style of "Xichan" that emerged a century ago when Shanghai was the "Paris of Asia" and is still alive today.

Food that touches, conflicts, and embraces

When different cultures come into unexpected contact and ultimately embrace each other, something wonderful is born.

At first, they may feel unfamiliar and experience conflict due to each other's stereotypes, but eventually they will realize that there is a point where compromise is possible, and then something unexpected and third will emerge.

For example, Fusha Dunlop speculates that although the Central Plains Chinese did not accept the dairy products consumed by the northern 'barbarians', they probably copied the process by which they made milk into cheese, solidifying the soybean water ground on a millstone to create tofu.

Doesn't every culture evolve through a process of contact, conflict, and inclusion?

Conversely, a culture that has no contact with the outside world and fears diversity stagnates or degenerates.

That is why the Korean subtitle of this book is ‘Chinese Gastronomic Anthropology.’

Author Fusha Dunlop became fascinated with Chinese cuisine while attending a local cooking school in Chengdu, Sichuan, during a year-long stay in the mid-1990s.

And I spent over ten years studying and exploring cuisines from all over China.

The 2008 book, Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper, which summarized the adventures, also became a hot topic in China's expat community at the time.

Before and after that, he published several bestselling recipe books covering Sichuan, Hunan, and Jiangnan cuisines, and he also constantly organized gourmet tours to introduce Chinese cuisine to Westerners.

The translators say:

The 1990s and 2000s were a time when the fruits of China's reform and opening-up policy were reaching their peak.

As China's economy grew at a breakneck pace and its doors opened wide to attract investment, countless foreigners flocked to the country.

Looking back, China at that time was a place where different cultures clashed noisily.

There were many misunderstandings and conflicts, but unlike today, it was a time when efforts to get along and accept each other were the prerequisite.

I think that the fact that Fusha Dunlop was able to freely explore the food cultures of all of China was largely due to the open atmosphere of the time, in addition to the fact that she was a Westerner.

This book is the culmination of the author's 30 years of dedication to Chinese food.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 22, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 552 pages | 666g | 140*205*27mm

- ISBN13: 9791169092708

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)