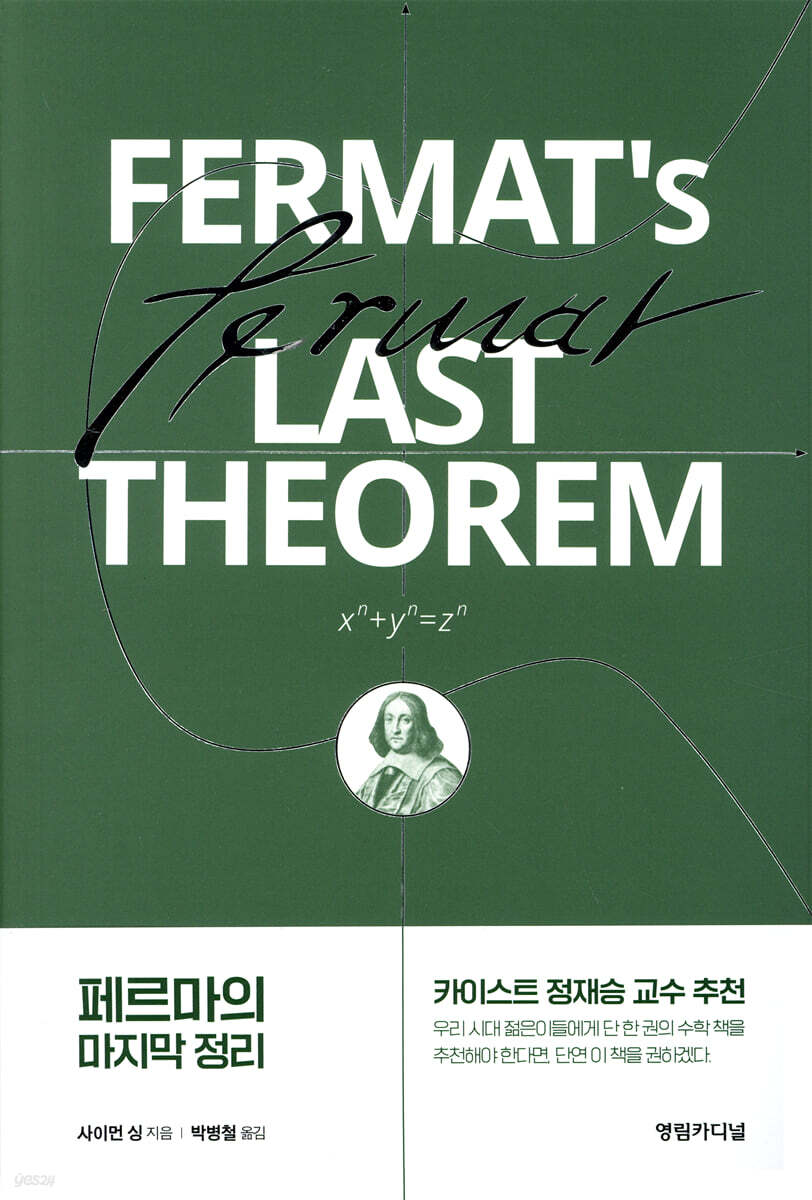

Fermat's Last Theorem

|

Description

Book Introduction

Highly recommended by Professor Jaeseung Jeong of KAIST!

If I had to recommend just one math book to young people of our time, it would definitely be Fermat's Last Theorem.

Because this book was the most special 'one math book' of my youth.

I truly learned the beauty of mathematics and the fierce passion of mathematicians from this book.

… … (omitted) … … The virtue of this book is that the history of mathematics over the past several hundred years is contained in a single story: the mathematical challenge of [Fermat's Last Theorem] was first posed, challenged by numerous mathematicians, and finally proven by Andrew Wiles.

The best way to become interested in mathematics is to understand it not as the 'study of numbers' but as 'the history of mathematicians trying to understand the world of numbers'.

If you're curious about what mathematics is, you'll find the answer in this book.

… … (omitted) … … This math book is more dramatic than any movie and more touching than any drama.

If you're someone who often finds yourself standing in front of a math textbook and exclaiming, "I don't understand why we have to learn this stuff!", I recommend this book to help you break down your prejudices about math.

If I had to recommend just one math book to young people of our time, it would definitely be Fermat's Last Theorem.

Because this book was the most special 'one math book' of my youth.

I truly learned the beauty of mathematics and the fierce passion of mathematicians from this book.

… … (omitted) … … The virtue of this book is that the history of mathematics over the past several hundred years is contained in a single story: the mathematical challenge of [Fermat's Last Theorem] was first posed, challenged by numerous mathematicians, and finally proven by Andrew Wiles.

The best way to become interested in mathematics is to understand it not as the 'study of numbers' but as 'the history of mathematicians trying to understand the world of numbers'.

If you're curious about what mathematics is, you'll find the answer in this book.

… … (omitted) … … This math book is more dramatic than any movie and more touching than any drama.

If you're someone who often finds yourself standing in front of a math textbook and exclaiming, "I don't understand why we have to learn this stuff!", I recommend this book to help you break down your prejudices about math.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

Detailed image

Publisher's Review

Finally, a shout of 'Eureka!' erupts.

The greatest mathematical puzzle in history has finally been solved after 350 years!

“ xn + yn = zn ; when n is an integer greater than or equal to 3,

There are no integer solutions x, y, z that satisfy this equation.

I proved this theorem in a wonderful way.

However, the margins of this book are too narrow, so I will not translate it here…

◆ For the past 350 years, mathematicians have had to endure harsh trials and tribulations while trying to recover their trampled pride due to these words left by Pierre de Fermat, a 17th-century French amateur mathematician, in the margin of Diophantus' book Arithmetica.

This was because no one had been able to reproduce this ‘proof’.

◆ Proving Fermat's Last Theorem was the most difficult task in the history of mathematics, but if you look at the theorem itself, its content is so simple that even an elementary school student could solve it.

However, it was the greatest riddle and difficult problem in the history of mathematics, to the point that even the greatest scholars of the time had to kneel before this “theorem.”

Over the years, countless people have dedicated their lives to proving this theorem, but the lock never seemed to open.

◆ However, British mathematician Andrew Wiles succeeded in proving this and finally won the Wolfskell Prize in 1997, opening a new chapter in the history of mathematics.

The moment he first encountered this "theorem" in a rural library as a boy, he vowed to dedicate his life to proving it. Despite countless stories of failure, he never gave up and persevered for many years.

His dream finally came true in his 40s.

This book, which weaves together his dream and the dreams of people who have been crazy about the 'beauty of mathematics' since the time of Pythagoras, into a single 'drama', presents to readers unfamiliar with mathematics the history of 'Fermat's Last Theorem' and the intense lives of great geniuses who have risen and fallen in an interesting way.

Mathematics is amazingly beautiful! And perfect!

A neat documentary that goes beyond the concept of problem-solving math books!

● A life goal set at age ten - and 30 years later

In 1963, Andrew Wiles, then a ten-year-old boy, encountered a book in a rural library and found a clear purpose in life.

Thirty years later, on June 23, 1993, Wiles, who had become a professor at Princeton University, proved Fermat's Last Theorem in a lecture at a conference held at the Isaac Newton Institute in Cambridge University. With a calm remark, "I think we should end it here," he put an end to Fermat's riddle that had plagued mathematicians for 350 years.

The lecture hall was filled with cheers and excitement that seemed to overflow, and the media from each country reported this as top news.

However, like other great works, Wiles' proof was also found to have one error, which put it in danger of being discarded.

After struggling for a year to correct the error, on September 19, 1994, Wiles succeeded in achieving a perfect proof by correcting the error in a moment of inspiration.

Then, on June 27, 1997, Wiles received the Wolfskell Prize and a prize of $50,000.

With this, the Wolfskell Prize finally found its owner after 89 years since its establishment, and at that time, the prize was about to expire in 10 years.

Andrew Wiles' success story alone cannot adequately explain the 350-year history of Fermat's Last Theorem.

At the same time, it is by no means easy to explain the history of Fermat's theorem to general readers who are not familiar with mathematics.

However, Simon Singh has masterfully described the history of Fermat's Last Theorem, that beautiful history of mathematics, in a style that anyone can easily understand through dramatic development of the story, and he appropriately cites the subtle feelings of mathematicians and the repercussions of the mathematical community.

Fermat's last theorem is as follows:

xn + yn = zn ; when n is an integer greater than or equal to 3,

There is no integer solution (x, y, z) that satisfies this equation.

To a non-mathematician, this might sound like a boring and insignificant theorem.

Even Carl Friedrich Gauss, who was called the prince of mathematics, declared, “Fermat’s Last Theorem is a speculative theorem of mathematics, and I am not particularly interested in it.”

However, as Simon Singh notes, the problem Fermat posed has been a subject of intense interest to mathematicians for centuries and has had a significant impact on the mathematical community as a whole.

As the 19th century drew to a close, most of the mathematicians working on Fermat's Last Theorem had died, leaving one of history's greatest puzzles in danger of being lost.

At that time, Paul Wolfskell, a 19th-century German businessman and amateur mathematician, was unable to overcome the pain of a broken heart and decided to commit suicide. Just before committing suicide, he read Ernst Kummer's paper on Fermat's theorem.

Then, suddenly, he discovered a flaw in Kummer's logic, and became so absorbed in this problem that he missed the scheduled time to commit suicide.

Although Wolfskell failed to solve this problem, he established the Wolfskell Prize to award the person who proves Fermat's Last Theorem, as a token of appreciation for the fact that it gave him a new lease on life.

This is not the only anecdote introduced in this book.

The story of Sophie Germain, a 19th-century French female mathematician who disguised herself as a man and studied this theorem to find a clue to its proof, and the innovative ideas of the genius Évariste Galois, who died in a duel at the young age of 20, are vividly described.

Galois's work later played an important role in Wiles' proof.

What is distinctive about Wiles' proof is that it uses techniques from several very different fields of mathematics.

Mathematicians usually do not venture beyond the boundaries of other mathematical fields.

However, Wiles's paper covers so many different areas of mathematics that it would be impossible for a specialist in any one field to understand it.

So, unusually, six reviewers were mobilized to review his thesis.

This meticulous vetting process allowed for the discovery of errors in his paper, which were ultimately successfully corrected through Wiles's dedicated efforts.

● Seven years of seclusion - and the first step toward "Great Unification Mathematics"!

While proving Fermat's theorem, Wiles performed all his calculations alone in complete isolation.

During the seven years he fought with Fermat, the only person who knew about his secret research was his wife.

Another important point is that much of his logic is based on the work of other mathematicians.

Among them, the most important one is the Taniyama-Shimura Conjecture, which was born in the 1950s.

This was a revolutionary idea created by Japanese mathematicians Yutaka Taniyama and Goro Shimura, linking two completely different fields of mathematics.

Later, a mathematician discovered that if the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture is correct, Fermat's Last Theorem is automatically proven.

In that sense, what Wiles proved was not actually Fermat's theorem, but the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture.

Ultimately, Wiles proved Fermat's Last Theorem and took the first step toward the enormous task of Grand Unified Mathematics.

Taniyama never saw his 'conjecture' proven.

He ended his life by suicide in 1958.

When we finish reading Wiles' "Proof," which will be recorded as one of the greatest achievements in the history of human civilization, and close the last page, we may shout "Eureka!"

The greatest mathematical puzzle in history has finally been solved after 350 years!

“ xn + yn = zn ; when n is an integer greater than or equal to 3,

There are no integer solutions x, y, z that satisfy this equation.

I proved this theorem in a wonderful way.

However, the margins of this book are too narrow, so I will not translate it here…

◆ For the past 350 years, mathematicians have had to endure harsh trials and tribulations while trying to recover their trampled pride due to these words left by Pierre de Fermat, a 17th-century French amateur mathematician, in the margin of Diophantus' book Arithmetica.

This was because no one had been able to reproduce this ‘proof’.

◆ Proving Fermat's Last Theorem was the most difficult task in the history of mathematics, but if you look at the theorem itself, its content is so simple that even an elementary school student could solve it.

However, it was the greatest riddle and difficult problem in the history of mathematics, to the point that even the greatest scholars of the time had to kneel before this “theorem.”

Over the years, countless people have dedicated their lives to proving this theorem, but the lock never seemed to open.

◆ However, British mathematician Andrew Wiles succeeded in proving this and finally won the Wolfskell Prize in 1997, opening a new chapter in the history of mathematics.

The moment he first encountered this "theorem" in a rural library as a boy, he vowed to dedicate his life to proving it. Despite countless stories of failure, he never gave up and persevered for many years.

His dream finally came true in his 40s.

This book, which weaves together his dream and the dreams of people who have been crazy about the 'beauty of mathematics' since the time of Pythagoras, into a single 'drama', presents to readers unfamiliar with mathematics the history of 'Fermat's Last Theorem' and the intense lives of great geniuses who have risen and fallen in an interesting way.

Mathematics is amazingly beautiful! And perfect!

A neat documentary that goes beyond the concept of problem-solving math books!

● A life goal set at age ten - and 30 years later

In 1963, Andrew Wiles, then a ten-year-old boy, encountered a book in a rural library and found a clear purpose in life.

Thirty years later, on June 23, 1993, Wiles, who had become a professor at Princeton University, proved Fermat's Last Theorem in a lecture at a conference held at the Isaac Newton Institute in Cambridge University. With a calm remark, "I think we should end it here," he put an end to Fermat's riddle that had plagued mathematicians for 350 years.

The lecture hall was filled with cheers and excitement that seemed to overflow, and the media from each country reported this as top news.

However, like other great works, Wiles' proof was also found to have one error, which put it in danger of being discarded.

After struggling for a year to correct the error, on September 19, 1994, Wiles succeeded in achieving a perfect proof by correcting the error in a moment of inspiration.

Then, on June 27, 1997, Wiles received the Wolfskell Prize and a prize of $50,000.

With this, the Wolfskell Prize finally found its owner after 89 years since its establishment, and at that time, the prize was about to expire in 10 years.

Andrew Wiles' success story alone cannot adequately explain the 350-year history of Fermat's Last Theorem.

At the same time, it is by no means easy to explain the history of Fermat's theorem to general readers who are not familiar with mathematics.

However, Simon Singh has masterfully described the history of Fermat's Last Theorem, that beautiful history of mathematics, in a style that anyone can easily understand through dramatic development of the story, and he appropriately cites the subtle feelings of mathematicians and the repercussions of the mathematical community.

Fermat's last theorem is as follows:

xn + yn = zn ; when n is an integer greater than or equal to 3,

There is no integer solution (x, y, z) that satisfies this equation.

To a non-mathematician, this might sound like a boring and insignificant theorem.

Even Carl Friedrich Gauss, who was called the prince of mathematics, declared, “Fermat’s Last Theorem is a speculative theorem of mathematics, and I am not particularly interested in it.”

However, as Simon Singh notes, the problem Fermat posed has been a subject of intense interest to mathematicians for centuries and has had a significant impact on the mathematical community as a whole.

As the 19th century drew to a close, most of the mathematicians working on Fermat's Last Theorem had died, leaving one of history's greatest puzzles in danger of being lost.

At that time, Paul Wolfskell, a 19th-century German businessman and amateur mathematician, was unable to overcome the pain of a broken heart and decided to commit suicide. Just before committing suicide, he read Ernst Kummer's paper on Fermat's theorem.

Then, suddenly, he discovered a flaw in Kummer's logic, and became so absorbed in this problem that he missed the scheduled time to commit suicide.

Although Wolfskell failed to solve this problem, he established the Wolfskell Prize to award the person who proves Fermat's Last Theorem, as a token of appreciation for the fact that it gave him a new lease on life.

This is not the only anecdote introduced in this book.

The story of Sophie Germain, a 19th-century French female mathematician who disguised herself as a man and studied this theorem to find a clue to its proof, and the innovative ideas of the genius Évariste Galois, who died in a duel at the young age of 20, are vividly described.

Galois's work later played an important role in Wiles' proof.

What is distinctive about Wiles' proof is that it uses techniques from several very different fields of mathematics.

Mathematicians usually do not venture beyond the boundaries of other mathematical fields.

However, Wiles's paper covers so many different areas of mathematics that it would be impossible for a specialist in any one field to understand it.

So, unusually, six reviewers were mobilized to review his thesis.

This meticulous vetting process allowed for the discovery of errors in his paper, which were ultimately successfully corrected through Wiles's dedicated efforts.

● Seven years of seclusion - and the first step toward "Great Unification Mathematics"!

While proving Fermat's theorem, Wiles performed all his calculations alone in complete isolation.

During the seven years he fought with Fermat, the only person who knew about his secret research was his wife.

Another important point is that much of his logic is based on the work of other mathematicians.

Among them, the most important one is the Taniyama-Shimura Conjecture, which was born in the 1950s.

This was a revolutionary idea created by Japanese mathematicians Yutaka Taniyama and Goro Shimura, linking two completely different fields of mathematics.

Later, a mathematician discovered that if the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture is correct, Fermat's Last Theorem is automatically proven.

In that sense, what Wiles proved was not actually Fermat's theorem, but the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture.

Ultimately, Wiles proved Fermat's Last Theorem and took the first step toward the enormous task of Grand Unified Mathematics.

Taniyama never saw his 'conjecture' proven.

He ended his life by suicide in 1958.

When we finish reading Wiles' "Proof," which will be recorded as one of the greatest achievements in the history of human civilization, and close the last page, we may shout "Eureka!"

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: July 25, 2022

- Page count, weight, size: 440 pages | 644g | 153*224*21mm

- ISBN13: 9788984012554

- ISBN10: 8984012556

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)