The mathematician who went to the art museum

|

Description

Book Introduction

Recommendations from experts in the fields of mathematics and education

Revised and expanded edition published amid rave reviews from the press and readers.

Painters have evolved art and perfected beauty by applying the mathematical principles discovered by mathematicians over a long period of time to the language of art, such as points and lines, planes and colors, perspective and symmetry.

It is no exaggeration to say that painters are the most beautiful mathematicians in human history.

Masaccio opened the way to overcoming the two-dimensionality of painting through perspective, and Dürer discovered the most beautiful aspect of humanity through the golden ratio.

Seurat and Mondrian captured the essence of color and form with just dots and lines, and Escher drew the principle of infinity based on Poincaré's model of the universe.

And Magritte proved on canvas that Euclidean geometry, which states that parallel lines do not intersect, may not be correct.

This book, interwoven with mythology and history, presents a fascinating account of how mathematics became a decisive force in changing the composition of art.

Since its first publication in 2018, "The Mathematician Who Went to the Art Museum" has received recommendations and support from researchers and educators at the forefront of the mathematics and education fields, as well as countless readers.

Thanks to this, it was honored with being selected as an excellent science book by the Ministry of Science and ICT and was able to establish itself as a bestseller in the science field for a long time.

Thanks to this, I had the opportunity to publish a revised and expanded edition.

In the revised and expanded edition, Bertrand Russell's paradox is illuminated from the perspective of set theory through Magritte's masterpiece, [The Treachery of Images].

Also, Daniel McRyse's painting, which brought the climax of [Hamlet] to canvas, summoned up the 'prisoner's dilemma'.

Among the Riemann hypothesis, one of the greatest challenges in mathematics, the irregularity of prime numbers was also explained from a new perspective through modern art works such as [Sieve of Eratosthenes] (by Rune Mills) and [Indivisible] (by Richard Kostelanetz).

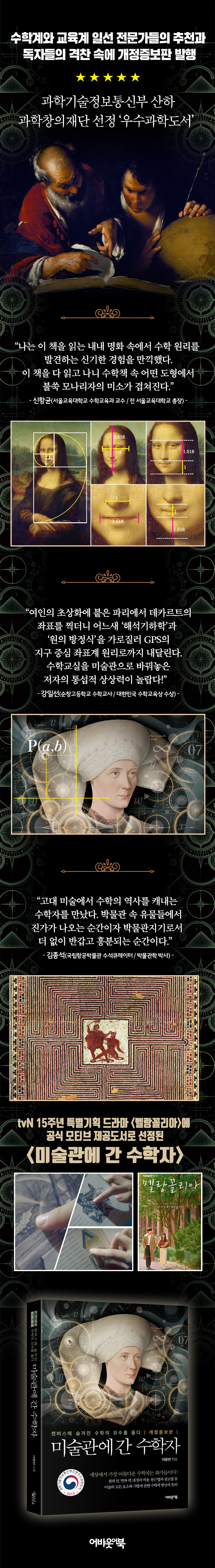

In addition, various topics were expanded, such as the story of how a fly attached to [Portrait of a Lady by Hopper] at the National Gallery in London became the cornerstone of analytic geometry through the 'equation of a circle' in the Cartesian coordinate system, and the background of how coordinate values on a vertical line led to the evolution of GPS in precise map making.

Revised and expanded edition published amid rave reviews from the press and readers.

Painters have evolved art and perfected beauty by applying the mathematical principles discovered by mathematicians over a long period of time to the language of art, such as points and lines, planes and colors, perspective and symmetry.

It is no exaggeration to say that painters are the most beautiful mathematicians in human history.

Masaccio opened the way to overcoming the two-dimensionality of painting through perspective, and Dürer discovered the most beautiful aspect of humanity through the golden ratio.

Seurat and Mondrian captured the essence of color and form with just dots and lines, and Escher drew the principle of infinity based on Poincaré's model of the universe.

And Magritte proved on canvas that Euclidean geometry, which states that parallel lines do not intersect, may not be correct.

This book, interwoven with mythology and history, presents a fascinating account of how mathematics became a decisive force in changing the composition of art.

Since its first publication in 2018, "The Mathematician Who Went to the Art Museum" has received recommendations and support from researchers and educators at the forefront of the mathematics and education fields, as well as countless readers.

Thanks to this, it was honored with being selected as an excellent science book by the Ministry of Science and ICT and was able to establish itself as a bestseller in the science field for a long time.

Thanks to this, I had the opportunity to publish a revised and expanded edition.

In the revised and expanded edition, Bertrand Russell's paradox is illuminated from the perspective of set theory through Magritte's masterpiece, [The Treachery of Images].

Also, Daniel McRyse's painting, which brought the climax of [Hamlet] to canvas, summoned up the 'prisoner's dilemma'.

Among the Riemann hypothesis, one of the greatest challenges in mathematics, the irregularity of prime numbers was also explained from a new perspective through modern art works such as [Sieve of Eratosthenes] (by Rune Mills) and [Indivisible] (by Richard Kostelanetz).

In addition, various topics were expanded, such as the story of how a fly attached to [Portrait of a Lady by Hopper] at the National Gallery in London became the cornerstone of analytic geometry through the 'equation of a circle' in the Cartesian coordinate system, and the background of how coordinate values on a vertical line led to the evolution of GPS in precise map making.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

[Preface: Attached to the Revised and Expanded Edition] A Tribute to the Painters of Mathematics

Chapter 1.

Mathematical principles that change the composition of paintings

Drawing the Distant World in Paintings - The Discovery of Perspective

Question Your Eyes! _Optical Illusions and the Golden Triangle

Artists Who Draw Equations _ The Properties of Equations and Proportional Relationships

The Joy of Falling into a Labyrinth: Labyrinths, Mazes, and Topology

In art and mathematics, the simpler the better! _The Principle of the Golden Rectangle

A Mathematician's Appreciation of the Golden Ratio _ Theory of Human Proportions

Is the pipe Russell is biting really a pipe? _Paradox and Dilemma

Chapter 2.

The history of mathematics in pictures

Encountering Ancient Mathematicians Through a Single Drawing: Mathematicians of the School of Athens

The Power to Prove the Existence of Invisible Numbers _ The Origin of Time and Numbers

Queen Dido and the Flower of Life - Kepler's Conjecture, the Equilateral Problem, and Knot Theory

History of the concept of numbers: One-way functions and the one-to-one correspondence principle

Portrait of a Mathematician _ Newton and the Compass

Thinking of 'circle' - wheel, sun, zero and soap bubbles

The Ring of Prometheus: Rediscovering the Ring Theory

How 'Difficult Numbers' Become Art _ 'The Sieve of Eratosthenes' and Prime Numbers

Chapter 3.

Painters with deep mathematical thinking

A Masterpiece That Broke the Frame of Euclidean Geometry: Distortion and Projective Geometry

The Cat Who Awakened to the Incompleteness of Mathematics - Quantum Mechanics and the Power of 7

A Mysterious Box that Comforts Mathematicians _Magic Square

Solving the implications of functions with pictures - Continuity and discontinuity

Noah's Ark as Seen by a Mathematician: Units and Precipitation

The Humanities of Sweet and Sour Apples: Vesica Piscis, the "Apple of Discord," and the Cycloid

Escher, the painter of mathematics: the principles of infinity and cycles

Analytical Geometry and the Paris Effect _ Cartesian Coordinate System

Chapter 4.

Math chat at a cafe next to the art museum

The Brilliant Fall of Phaethon: The Birth of the Calendar

How much of myself is inside me? _The problem of fractals and dimensions

Thoughts that blossom from a small dot and a thin line _Reminiscing about binary in the digital world

A Formula More Dreadful Than the Sword of Hercules: The Power of Exponentiation

Spiders, Shedding Their Disgusting Skin: The Myths, Science, and Mathematics of Spider Webs

Math Problems on Love, Birthdays, and Gambling - Fun Applications of Probability

A cup of coffee at a cafe next to the art museum - Siren and the mathematics of sound

Search for works / Search for people / Search for references

Chapter 1.

Mathematical principles that change the composition of paintings

Drawing the Distant World in Paintings - The Discovery of Perspective

Question Your Eyes! _Optical Illusions and the Golden Triangle

Artists Who Draw Equations _ The Properties of Equations and Proportional Relationships

The Joy of Falling into a Labyrinth: Labyrinths, Mazes, and Topology

In art and mathematics, the simpler the better! _The Principle of the Golden Rectangle

A Mathematician's Appreciation of the Golden Ratio _ Theory of Human Proportions

Is the pipe Russell is biting really a pipe? _Paradox and Dilemma

Chapter 2.

The history of mathematics in pictures

Encountering Ancient Mathematicians Through a Single Drawing: Mathematicians of the School of Athens

The Power to Prove the Existence of Invisible Numbers _ The Origin of Time and Numbers

Queen Dido and the Flower of Life - Kepler's Conjecture, the Equilateral Problem, and Knot Theory

History of the concept of numbers: One-way functions and the one-to-one correspondence principle

Portrait of a Mathematician _ Newton and the Compass

Thinking of 'circle' - wheel, sun, zero and soap bubbles

The Ring of Prometheus: Rediscovering the Ring Theory

How 'Difficult Numbers' Become Art _ 'The Sieve of Eratosthenes' and Prime Numbers

Chapter 3.

Painters with deep mathematical thinking

A Masterpiece That Broke the Frame of Euclidean Geometry: Distortion and Projective Geometry

The Cat Who Awakened to the Incompleteness of Mathematics - Quantum Mechanics and the Power of 7

A Mysterious Box that Comforts Mathematicians _Magic Square

Solving the implications of functions with pictures - Continuity and discontinuity

Noah's Ark as Seen by a Mathematician: Units and Precipitation

The Humanities of Sweet and Sour Apples: Vesica Piscis, the "Apple of Discord," and the Cycloid

Escher, the painter of mathematics: the principles of infinity and cycles

Analytical Geometry and the Paris Effect _ Cartesian Coordinate System

Chapter 4.

Math chat at a cafe next to the art museum

The Brilliant Fall of Phaethon: The Birth of the Calendar

How much of myself is inside me? _The problem of fractals and dimensions

Thoughts that blossom from a small dot and a thin line _Reminiscing about binary in the digital world

A Formula More Dreadful Than the Sword of Hercules: The Power of Exponentiation

Spiders, Shedding Their Disgusting Skin: The Myths, Science, and Mathematics of Spider Webs

Math Problems on Love, Birthdays, and Gambling - Fun Applications of Probability

A cup of coffee at a cafe next to the art museum - Siren and the mathematics of sound

Search for works / Search for people / Search for references

Detailed image

Publisher's Review

Beautiful pictures instead of complex formulas

Enjoy the charm of mathematics!

This book tells a captivating story, interwoven with myth and history, of how mathematics became a decisive factor in changing the composition of painting in the history of art.

In addition, we unearth works of art that hold value as important historical materials inscribed with the history of mathematics, and delve into the hidden stories behind them.

Above all, what makes this book special is that it uses artwork to explain difficult mathematical principles and formulas learned in middle and high school math classes in an easy and fun way.

The author explains various mathematical principles, such as the Pythagorean theorem, axioms and equations, equality and proportion, powers, functions, continuity and discontinuity, etc., without complex formulas, and by linking them with famous paintings that seem to have nothing to do with mathematics.

For example, while introducing Paul Cézanne's still life painting "Apples and Oranges," he explains why apples and almost all other fruits are round by connecting the "Dido's problem" from Greek mythology to the "equilateral triangle problem" in mathematics.

In Georges Seurat's "A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Jatte," we retraceve the process by which painters came to realize that the basic unit of a painting was the "point," and examine how digital technology originated from binary systems through the relationship between painting's "pointillism" and video art's "pixel."

While appreciating Bruegel's masterpiece, "The Tower of Babel," it is refreshing to see that the Tower of Babel was destined to collapse because of its golden triangle shape, with a base angle of 72 degrees.

The story is that if the Tower of Babel had known the 'principle of the angle of rest' in 'granular mechanics' when it was built, the Tower of Babel might not have collapsed.

In addition, the labyrinth mosaic, believed to be from the ancient Roman era, explains the topology hidden in the principles of the labyrinth, and the compass that appears in William Blake's portrait of Newton and religious paintings explains the creation myths of the East and the West and the biblical story that God created the world with mathematics.

After reading this book, you will nod in agreement with the author's statement that "the most beautiful mathematicians in human history are painters."

Painters have evolved art and perfected beauty by applying the mathematical principles discovered by mathematicians over a long period of time to the language of art, such as points and lines, planes and colors, perspective and symmetry.

“You can’t draw properly without knowing arithmetic and geometry.”

- Pamphilus -

The honeymoon between art and mathematics has been going on for quite some time historically.

Leon Battista Alberti, a Renaissance art theorist and mathematician, quoted the ancient Macedonian painter Pamphilus in his 1435 book On Painting:

“A painter must be well-versed in all fields, but especially in geometry.

I wholeheartedly agree with the words of the great ancient painter Pamphilus, who said that one cannot paint properly without knowing arithmetic and geometry.”

Many painters of the time sympathized with Alberti's views.

Painters have applied the mathematical principles discovered by mathematicians over a long period of time to the language of art, such as points and lines, planes and colors, perspective and symmetry, and projected them into their works.

Art, called the flower of emotion, has evolved through meeting mathematics, armed with cold reason and logical thinking.

Euclidean geometry, which states that parallel lines never intersect, may not be correct.

- René Magritte -

The greatest event in which mathematics was reflected in art was the discovery of perspective.

The Holy Trinity, painted by the Italian painter Masaccio, is the first Renaissance painting to demonstrate perspective.

At the time, it was a well-known fact that objects appear smaller the further away they are, but calculating this mathematically and applying it to artwork required a paradigm shift.

Expressing a three-dimensional effect by creating a distant and near effect on a flat surface was an innovative technique that transcended the two-dimensionality of painting and led to a three-dimensional world.

Piero della Francesca, a 15th-century painter and mathematician, discovered the existence of a vanishing point through perspective.

In the word 'vanishing point', 'vanishing' means disappearing and disappearing.

In perspective, when two parallel lines are drawn non-parallel, the two lines meet at a point in the distance, creating a sense of perspective. The point where the two lines meet is the vanishing point.

Magritte, a modern surrealist painter, refuted the definition of Euclid, an ancient Greek mathematician, that “parallel lines are straight lines that never meet no matter how much they are extended,” through his painting “Euclidean Walk.” This also contains the principle of optical illusion using perspective.

In this way, perspective, a product of mathematics, became a basic element of painting during the Renaissance and had a tremendous influence on the development of art from the modern era to the present day.

“I drew a man and a woman with numbers.”

- Albrecht Dürer -

The mathematical principle that shook the history of art as much as perspective is the 'golden ratio'.

If perspective made the evolution of art possible, the golden ratio can be said to have artistically perfected art.

What countless artists have pursued throughout their lives is the optimal ratio for capturing the most ideal beauty on canvas, and that ratio is almost identical to the golden ratio suggested by mathematicians.

Dürer, a master of the German Renaissance, devoted all his energy to finding the golden ratio that would complete the perfect beauty of the human body, to the point of saying, “I drew men and women with numbers.”

The golden ratio has been proven by masters of all time, from Dürer to Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Mondrian.

For example, if you look closely at the figure and face of the world's most famous masterpiece, the Mona Lisa, you will see that it is surprisingly close to the golden ratio, and the base angles of Bruegel's Tower of Babel match the golden triangle.

The reason why people cannot help but focus on the works of Mondrian, a modern painter who depicted the essence of things by focusing on points, lines, and planes, is because of the ratio of the golden rectangle.

Recommendations from experts in the fields of mathematics and education

Revised and expanded edition published amid rave reviews from the press and readers.

Since its first publication in 2018, "The Mathematician Who Went to the Art Museum" has received tremendous recommendations and support from researchers and educators at the forefront of the mathematics and education fields, as well as countless readers.

Thanks to this, it was honored with being selected as an excellent science book by the Ministry of Science and ICT and was able to establish itself as a bestseller in the science field for a long time.

Thanks to this, I had the opportunity to publish a revised and expanded edition.

In the revised and expanded edition, Bertrand Russell's paradox is illuminated from the perspective of set theory through Magritte's masterpiece, The Treachery of Images.

Also, the 'prisoner's dilemma' was evoked in Daniel McRyse's painting, which brought the climax of Hamlet to canvas.

The irregularity of prime numbers, one of the greatest challenges in mathematics, the Riemann hypothesis, was explained from a new perspective through modern art pieces such as “The Sieve of Eratosthenes” (by Rune Mills) and “Indivisibility” (by Richard Kostelanetz).

In addition, the book richly expands on various topics, including the story of how a fly attached to Hopper's Portrait of a Lady at the National Gallery in London became the cornerstone of analytic geometry through the 'equation of a circle' in the Cartesian coordinate system, and how coordinate values on a vertical line led to the evolution of GPS in precise mapmaking.

Enjoy the charm of mathematics!

This book tells a captivating story, interwoven with myth and history, of how mathematics became a decisive factor in changing the composition of painting in the history of art.

In addition, we unearth works of art that hold value as important historical materials inscribed with the history of mathematics, and delve into the hidden stories behind them.

Above all, what makes this book special is that it uses artwork to explain difficult mathematical principles and formulas learned in middle and high school math classes in an easy and fun way.

The author explains various mathematical principles, such as the Pythagorean theorem, axioms and equations, equality and proportion, powers, functions, continuity and discontinuity, etc., without complex formulas, and by linking them with famous paintings that seem to have nothing to do with mathematics.

For example, while introducing Paul Cézanne's still life painting "Apples and Oranges," he explains why apples and almost all other fruits are round by connecting the "Dido's problem" from Greek mythology to the "equilateral triangle problem" in mathematics.

In Georges Seurat's "A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Jatte," we retraceve the process by which painters came to realize that the basic unit of a painting was the "point," and examine how digital technology originated from binary systems through the relationship between painting's "pointillism" and video art's "pixel."

While appreciating Bruegel's masterpiece, "The Tower of Babel," it is refreshing to see that the Tower of Babel was destined to collapse because of its golden triangle shape, with a base angle of 72 degrees.

The story is that if the Tower of Babel had known the 'principle of the angle of rest' in 'granular mechanics' when it was built, the Tower of Babel might not have collapsed.

In addition, the labyrinth mosaic, believed to be from the ancient Roman era, explains the topology hidden in the principles of the labyrinth, and the compass that appears in William Blake's portrait of Newton and religious paintings explains the creation myths of the East and the West and the biblical story that God created the world with mathematics.

After reading this book, you will nod in agreement with the author's statement that "the most beautiful mathematicians in human history are painters."

Painters have evolved art and perfected beauty by applying the mathematical principles discovered by mathematicians over a long period of time to the language of art, such as points and lines, planes and colors, perspective and symmetry.

“You can’t draw properly without knowing arithmetic and geometry.”

- Pamphilus -

The honeymoon between art and mathematics has been going on for quite some time historically.

Leon Battista Alberti, a Renaissance art theorist and mathematician, quoted the ancient Macedonian painter Pamphilus in his 1435 book On Painting:

“A painter must be well-versed in all fields, but especially in geometry.

I wholeheartedly agree with the words of the great ancient painter Pamphilus, who said that one cannot paint properly without knowing arithmetic and geometry.”

Many painters of the time sympathized with Alberti's views.

Painters have applied the mathematical principles discovered by mathematicians over a long period of time to the language of art, such as points and lines, planes and colors, perspective and symmetry, and projected them into their works.

Art, called the flower of emotion, has evolved through meeting mathematics, armed with cold reason and logical thinking.

Euclidean geometry, which states that parallel lines never intersect, may not be correct.

- René Magritte -

The greatest event in which mathematics was reflected in art was the discovery of perspective.

The Holy Trinity, painted by the Italian painter Masaccio, is the first Renaissance painting to demonstrate perspective.

At the time, it was a well-known fact that objects appear smaller the further away they are, but calculating this mathematically and applying it to artwork required a paradigm shift.

Expressing a three-dimensional effect by creating a distant and near effect on a flat surface was an innovative technique that transcended the two-dimensionality of painting and led to a three-dimensional world.

Piero della Francesca, a 15th-century painter and mathematician, discovered the existence of a vanishing point through perspective.

In the word 'vanishing point', 'vanishing' means disappearing and disappearing.

In perspective, when two parallel lines are drawn non-parallel, the two lines meet at a point in the distance, creating a sense of perspective. The point where the two lines meet is the vanishing point.

Magritte, a modern surrealist painter, refuted the definition of Euclid, an ancient Greek mathematician, that “parallel lines are straight lines that never meet no matter how much they are extended,” through his painting “Euclidean Walk.” This also contains the principle of optical illusion using perspective.

In this way, perspective, a product of mathematics, became a basic element of painting during the Renaissance and had a tremendous influence on the development of art from the modern era to the present day.

“I drew a man and a woman with numbers.”

- Albrecht Dürer -

The mathematical principle that shook the history of art as much as perspective is the 'golden ratio'.

If perspective made the evolution of art possible, the golden ratio can be said to have artistically perfected art.

What countless artists have pursued throughout their lives is the optimal ratio for capturing the most ideal beauty on canvas, and that ratio is almost identical to the golden ratio suggested by mathematicians.

Dürer, a master of the German Renaissance, devoted all his energy to finding the golden ratio that would complete the perfect beauty of the human body, to the point of saying, “I drew men and women with numbers.”

The golden ratio has been proven by masters of all time, from Dürer to Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Mondrian.

For example, if you look closely at the figure and face of the world's most famous masterpiece, the Mona Lisa, you will see that it is surprisingly close to the golden ratio, and the base angles of Bruegel's Tower of Babel match the golden triangle.

The reason why people cannot help but focus on the works of Mondrian, a modern painter who depicted the essence of things by focusing on points, lines, and planes, is because of the ratio of the golden rectangle.

Recommendations from experts in the fields of mathematics and education

Revised and expanded edition published amid rave reviews from the press and readers.

Since its first publication in 2018, "The Mathematician Who Went to the Art Museum" has received tremendous recommendations and support from researchers and educators at the forefront of the mathematics and education fields, as well as countless readers.

Thanks to this, it was honored with being selected as an excellent science book by the Ministry of Science and ICT and was able to establish itself as a bestseller in the science field for a long time.

Thanks to this, I had the opportunity to publish a revised and expanded edition.

In the revised and expanded edition, Bertrand Russell's paradox is illuminated from the perspective of set theory through Magritte's masterpiece, The Treachery of Images.

Also, the 'prisoner's dilemma' was evoked in Daniel McRyse's painting, which brought the climax of Hamlet to canvas.

The irregularity of prime numbers, one of the greatest challenges in mathematics, the Riemann hypothesis, was explained from a new perspective through modern art pieces such as “The Sieve of Eratosthenes” (by Rune Mills) and “Indivisibility” (by Richard Kostelanetz).

In addition, the book richly expands on various topics, including the story of how a fly attached to Hopper's Portrait of a Lady at the National Gallery in London became the cornerstone of analytic geometry through the 'equation of a circle' in the Cartesian coordinate system, and how coordinate values on a vertical line led to the evolution of GPS in precise mapmaking.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 7, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 402 pages | 150*210*30mm

- ISBN13: 9791192229669

- ISBN10: 1192229665

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)