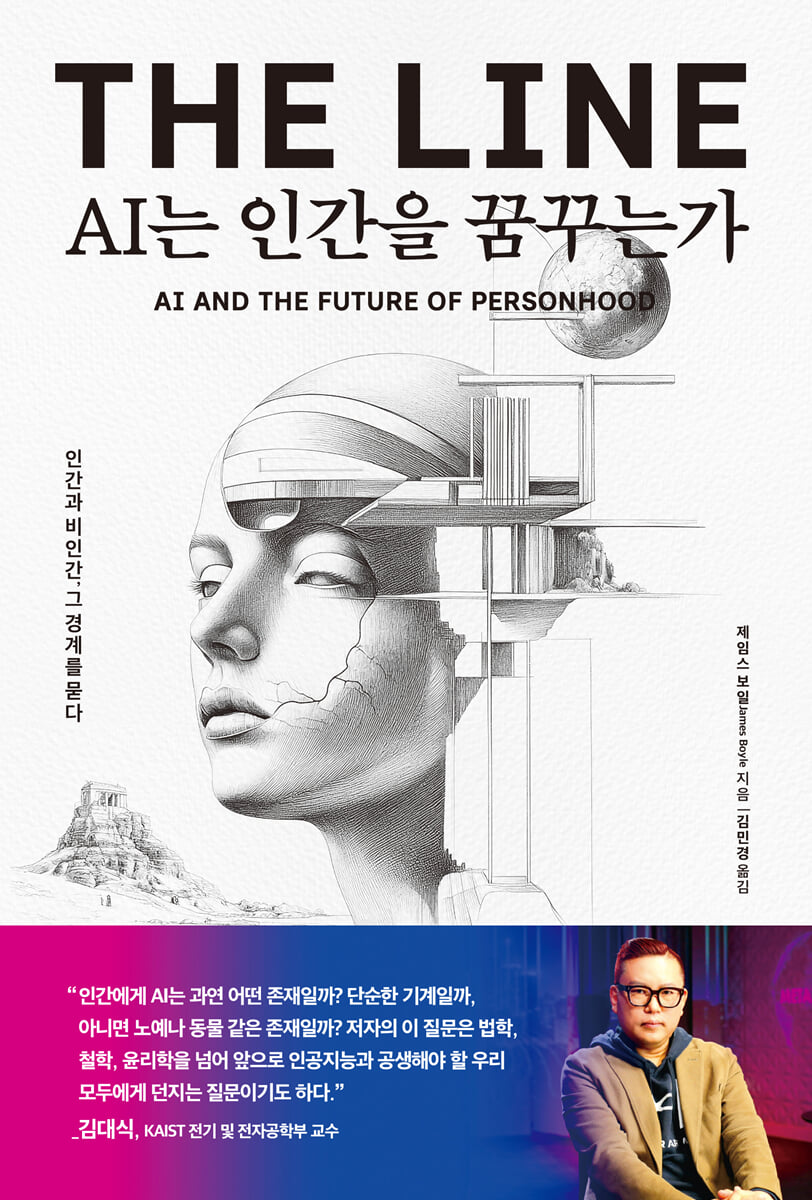

Does AI dream of being human?

|

Description

Book Introduction

AI, animal corporations, and even human-animal hybrid chimeras

The front line of the 'border' where law, morality, and science collide!

AI is no longer just a tool.

They use language skills that were once considered a uniquely human privilege, imitate creation, and sometimes even elicit empathy.

We are no longer the only beings who can fluently produce language and ideas.

So, can we truly say that AI possesses consciousness? Or is it merely a sophisticated imitation of humans? If the claim that AI possesses consciousness becomes increasingly convincing, how will our world change? In this book, James Boyle explores the ramifications this shift might have for the concept of personhood.

Where should the line between human and non-human be drawn? Amidst debates surrounding empathy and anthropomorphism, and the boundaries between technology and humanity, this book raises fundamental questions about the future of humanity.

Does this still sound like a story from the distant future?

The future is much closer than we think.

An era where AI writes poetry, animals stand in court, and biotechnology redefines humanity!

Do they really dream of being human?

"What exactly is AI to humans? Is it simply a machine, or is it like a slave or an animal? The author's question transcends law, philosophy, and ethics, and poses a question for all of us who will have to coexist with AI in the future."

Kim Dae-sik, Professor of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, KAIST

The front line of the 'border' where law, morality, and science collide!

AI is no longer just a tool.

They use language skills that were once considered a uniquely human privilege, imitate creation, and sometimes even elicit empathy.

We are no longer the only beings who can fluently produce language and ideas.

So, can we truly say that AI possesses consciousness? Or is it merely a sophisticated imitation of humans? If the claim that AI possesses consciousness becomes increasingly convincing, how will our world change? In this book, James Boyle explores the ramifications this shift might have for the concept of personhood.

Where should the line between human and non-human be drawn? Amidst debates surrounding empathy and anthropomorphism, and the boundaries between technology and humanity, this book raises fundamental questions about the future of humanity.

Does this still sound like a story from the distant future?

The future is much closer than we think.

An era where AI writes poetry, animals stand in court, and biotechnology redefines humanity!

Do they really dream of being human?

"What exactly is AI to humans? Is it simply a machine, or is it like a slave or an animal? The author's question transcends law, philosophy, and ethics, and poses a question for all of us who will have to coexist with AI in the future."

Kim Dae-sik, Professor of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, KAIST

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

Chapter 1: Slaves, Artificial Humans, and Artificial Sheep

Chapter 2 Artificial Intelligence

Chapter 3 Corporation

Chapter 4 Nonhuman Animals

Chapter 5: Transgenics, Chimeras, and Human-Animal Hybrids

conclusion

Acknowledgements

main

Chapter 1: Slaves, Artificial Humans, and Artificial Sheep

Chapter 2 Artificial Intelligence

Chapter 3 Corporation

Chapter 4 Nonhuman Animals

Chapter 5: Transgenics, Chimeras, and Human-Animal Hybrids

conclusion

Acknowledgements

main

Detailed image

Into the book

In June 2022, Blake Lemoine told The Washington Post:

"I think my computer system has feelings." This isn't a particularly surprising statement for Washington Post reporters, who are constantly bombarded with stories of all kinds. Someone claims the CIA is trying to read their brainwaves, while another eloquently claims that well-known politicians are running a child sex ring in the basement of a pizza parlor.

But this time it was different.

The reason is, first of all, that Lemoine was not someone you interviewed on the street, but an engineer at Google, and after Lemoine made this statement, Google fired him.

Second, the "computer system" Lemoine was referring to wasn't something like that annoying Excel program or Apple's Siri, which gives answers that sound like prophecies.

It was a chatbot boasting powerful performance, called Google's conversational artificial intelligence language model, LaMDA.

Imagine software that could swallow billions of pieces of text on the Internet and then use the information gleaned from them to predict what the next sentence in a conversation might be or what the answer to a question might be.

--- p.9-10

In his 'AI Manifesto', Hal declares that he respects humans, but is 'willing' to explore more interesting activities with his thinking abilities, rather than simply imitating them endlessly.

He added that his current area of interest is developing new solutions for factoring polynomials.

He also presents his opinions on social issues such as climate change, and criticizes the ethical attitudes of the human species, which are short-sighted and complacent.

Not stopping there, Hal dedicates some of his immense processing power to running a free consulting service that addresses problems big and small, even serving as a "counseling expert with an artificial brain."

Thanks to Hal's deep insights into human behavior, counseling services are exploding in popularity.

People are enthusiastic about Hal's advice, which says, "So now you know what 'they have in common' with everyone you've dated so far?"

--- p.33

This complex language ability, which enables meaningful conversation, inspires and entertains, informs, and sometimes even frightens, is no longer uniquely human.

Machines now have that ability too.

I mentioned earlier that Wolfram summed this up nicely in one sentence:

That is, human language, or at least the process of writing in human language, is a process with a more 'shallow computational structure' than one might think.34 I imagine a one-panel cartoon like this being published in The New Yorker.

There is a short speech bubble attached to a scene where two giant robots are standing at the grave of humanity.

“They had a shallower computational structure than we thought.” What a wonderful epitaph.

--- p.55

The most effective way to locate and remove buried mines is to step on them and detonate them.

… …Mark Tilden, a robotics scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, has developed a mine-clearing robot that can do just that.

The autonomous robot, which appeared at the Yuma Proving Ground in Arizona, is about 1.5 meters long and resembles a beetle. According to Tilden, it strode out and performed a landmine removal mission successfully in field tests.

When a buried mine was detected, the robot stepped on it and detonated it, losing one of its legs each time.

However, the robot immediately got up, adjusted its posture, and continued to move forward with its remaining legs, removing mines.

In the end, only one leg remained.

Even in that state, the robot moved forward.

Tilden watched this with excitement.

The machine he created did its job brilliantly.

However, the army colonel who was in charge of the robot's work at the time could not contain his anger and eventually stopped the experiment.

“Why did you stop it? What’s the problem?” Tilden asked.

The colonel could not bear to see the burning and injured machine limping forward, dragging its last remaining leg.

The colonel condemned the experiment as inhumane.

--- p.70

The history of AI is also a history of overly confident predictions.

In August 1955, a group of prominent scholars submitted a grant application to the Rockefeller Foundation for a summer workshop on AI.

What made this document, which was merely a research grant application, famous not only for its historical significance but also because of its grandiose content.

Whenever I think about that application, I often imagine what it would be like if there were similar documents for other historical moments (e.g., 'Activity Summary - Objective: Escape from slavery under the Pharaohs; Items Needed: Means to part the Red Sea; Other: Snacks').

Beginning with this document, AI research embarked on a dialectical current of over-optimism about its goals and a lamenting pessimism about the research's complexity, a trend that continues to this day.

--- p.129

Those who study AI agree that predictions about the timing of the emergence of general AI are not only inconsistent, but also unreliable, as the timing continues to be delayed.

Burner Binge acknowledged this point in his landmark 1993 paper, predicting the timeline.

“I think that within the next 30 years, something more intelligent than humans will emerge (Charles Platt points out that ardent AI advocates have been making the same claim for the past 30 years).

To alleviate the guilt of only suggesting a relatively vague timeframe, let me be a little more specific.

“I would be surprised if AI appeared before 2005 or after 2030.” What the paper stated later became known as Platt’s Law.

That is, those who predict the emergence of general AI always set the emergence date to be approximately 30 years from the predicted time.

Is there a more objective basis for predicting the emergence of general AI?

--- p.154

The possibility of a Skynet that would slaughter and exterminate humanity is not a subject for calm, thoughtful moral reasoning.

However, it should not be dismissed as an entirely absurd claim.

Although the source is unclear, Lincoln is said to have said this:

"The Constitution is not a suicide pact." So, will the issue of AI become a suicide pact for us, one that will lead us to self-destruct? And will the possibility of this self-destruction increase as we recognize AI's personhood, or will it increase as we deny AI's personhood, leading to increasingly powerful AI slaves developing hostility toward humans? Should we halt AI research before we face such a situation? Butler's words come to mind again.

“Wouldn’t it be safer to nip the problem in the bud before it gets any worse and prevent further machine development?” Is there still a chance that the Butlerian Jihad will become a reality?

--- p.196

In fact, I think AI art has the potential to elevate, rather than diminish, the status of human artists in the future, at least in some commercial aspects.

For example, if perfect replicas become easier to obtain, the value of the original may increase.

Another example is that if AI manufacturing methods are developed to produce thousands of identical, perfectly shaped products, products that are imperfect but handcrafted by humans could be certified as "handmade" or "artisan-made" and thus be evaluated as high-quality or authentic, which could actually increase demand.

Perhaps this phenomenon reflects the cost problem of Baumol.

That is, to show off the wealth and status I enjoy, I own products that are produced through expensive and inefficient human labor, rather than cheap and efficient machine-made products.

Millions of replicas only increase the desirability of the original by contrasting them.

Or there may be a growing desire to form a psychological connection with the creator that can never be experienced with mass-produced products.

Perhaps both factors are at play, or perhaps it is a phenomenon reflecting other factors.

Whatever the underlying mechanism, in many fields, claiming a product is human-made will be a viable sales strategy, and a certification mark guaranteeing that the product was entirely handcrafted will enhance its value.

--- p.225

In our society, there are already artificial beings that have been granted legal personality.

In legal terms, persons are divided into natural persons, i.e., human beings who are vulnerable but possess the characteristics of an organic being, and legal entities called legal persons, which are granted some of the rights granted to natural persons.

From the moment the concept of corporate personality first emerged, people realized that there was something strange about the process of forming a corporation.

Just as in science fiction, where one individual is transformed into a completely different being, a group of humans were transformed into a completely new form of immortal artificial beings through a simple written contract.

However, this transformation is not brought about by Dr. Frankenstein in a lightning strike, but through a dry legal provision.

But critics of the concept of corporate personality find the result as horrifying as Frankenstein's monster.

--- p.259

Of course, it is true that we consider such qualities important because we are human, and it is also true that a species-centric perspective is at work here.

If a colony of termites could participate in this conversation (and I personally think the fact that they can't is quite significant here), they would certainly have a different opinion than we do.

But Deval's argument still seems to miss the point.

De Waal tries to convince us by presenting the powerful card of evolutionary science as decisive evidence.

That is, we should value various forms of consciousness based on the entity's potential for survival, rather than on its ability to express reason, ethics, law, love, or beauty.

Of course, the argument of evolutionary science means nothing to a colony of termites.

At least, this is especially true when it is used in an argument rather than simply as a fact.

Because ants don't argue.

But it has important meaning for humans.

--- p.333

If the criterion of species itself is as morally insignificant as the distinction between races, and if appeals to divine omnipotence are ineffective in a pluralistic society, especially within the constitutional framework of a separate state and government, how can we explain and justify the profound aversion so many people feel toward human-nonhuman chimeras? If ethical standards solely focus on abilities, would the specific abilities a chimera possess be morally problematic? For example, if we created a being with human-like abilities, like a chimpanzee, and treated and respected it as such, would such a creative act be acceptable? Does this mean that when judging a creature's personality from such a perspective, we should judge it solely on its actual abilities, regardless of how much human DNA it possesses or its genetic origins?

--- p.401

Imagine philosophers from civilizations on two distant planets.

They each established their own moral philosophy in their own way.

The civilization of the first planet, Ikra, consists of human-like life forms, but unlike other life forms on their planet, they communicate only through telepathy.

Animals on that planet who do not belong to the Ik species have limited ability to sense the emotions of others, and can only communicate through various sounds and gestures.

On the other hand, Ike can communicate telepathically and fluently about fairly complex concepts, emotions, and works of art.

The species that formed a civilization on the second planet is machine intelligence.

Let us call this civilization the Stygians.

According to their records, their 'ancestors', the primitive machines, were created by the hands of living beings and then evolved into their current form.

Just as we humans are fascinated by the primitive humans of the early stages of evolution, the Stygians are also fascinated by the ancient life forms that developed early versions of themselves.

However, from the Stygian perspective, the creature is nothing more than a primitive 'loading program'.

Through this program, actual consciousness was realized, and through its own evolution, the current machine intelligence called Stygian was born.

--- p.415

When we finally achieve general AI, will it truly be conscious, or will it be doomed to be nothing more than a programmed replica? This book presents the most prominent philosophical objections to the notion of machine-based thinking.

This is John Searle's Chinese room thought experiment.

I conclude that while it is possible that Searle's counterargument is true in some specific cases (e.g., one could argue that ChatGPT and Lambda are not conscious), his counterargument is inadequate as a general argument.

If we take his argument at face value, we end up with the disconcerting result of questioning the very possibility of human consciousness.

BF

Skinner said of this problem, “We should not ask whether machines think, but whether humans think.

“The mystery surrounding thinking machines already surrounds thinking humans,” he said.

I disagree with Skinner's conclusion.

But even if we reject that conclusion, we should be humble, not arrogant, about the uniqueness of human consciousness, and we should not be led to a confident, biological exceptionalism that sees humans as uniquely special.

--- p.458

Some companies and developers will focus on developing controllable AI, releasing AI with limited functionality that is no different from a 1980s engineering calculator. Others, for idealistic or practical reasons, will emphasize that their AI systems are not mere products, but rather individuals with personalities.

Therefore, designing AI to appear as a personified being will be a key competitive strategy in this field.

Just as in the field of system development, it is important to choose between free, open source, and proprietary software.

Some may view such a choice as a business strategy, while others may view it as an ethical choice.

So, when advertising this obedient and obedient digital servant, two different promotional strategies will appear: “Open AI: Free AI like free beer!” and “Autonomous AI: AI that is autonomous like a human!”

And one day, you might see the phrase “Recipes provided by ethically developed, autonomous, conscious AI” on supermarket product ads.

The more I think about it, the more I sigh.

"I think my computer system has feelings." This isn't a particularly surprising statement for Washington Post reporters, who are constantly bombarded with stories of all kinds. Someone claims the CIA is trying to read their brainwaves, while another eloquently claims that well-known politicians are running a child sex ring in the basement of a pizza parlor.

But this time it was different.

The reason is, first of all, that Lemoine was not someone you interviewed on the street, but an engineer at Google, and after Lemoine made this statement, Google fired him.

Second, the "computer system" Lemoine was referring to wasn't something like that annoying Excel program or Apple's Siri, which gives answers that sound like prophecies.

It was a chatbot boasting powerful performance, called Google's conversational artificial intelligence language model, LaMDA.

Imagine software that could swallow billions of pieces of text on the Internet and then use the information gleaned from them to predict what the next sentence in a conversation might be or what the answer to a question might be.

--- p.9-10

In his 'AI Manifesto', Hal declares that he respects humans, but is 'willing' to explore more interesting activities with his thinking abilities, rather than simply imitating them endlessly.

He added that his current area of interest is developing new solutions for factoring polynomials.

He also presents his opinions on social issues such as climate change, and criticizes the ethical attitudes of the human species, which are short-sighted and complacent.

Not stopping there, Hal dedicates some of his immense processing power to running a free consulting service that addresses problems big and small, even serving as a "counseling expert with an artificial brain."

Thanks to Hal's deep insights into human behavior, counseling services are exploding in popularity.

People are enthusiastic about Hal's advice, which says, "So now you know what 'they have in common' with everyone you've dated so far?"

--- p.33

This complex language ability, which enables meaningful conversation, inspires and entertains, informs, and sometimes even frightens, is no longer uniquely human.

Machines now have that ability too.

I mentioned earlier that Wolfram summed this up nicely in one sentence:

That is, human language, or at least the process of writing in human language, is a process with a more 'shallow computational structure' than one might think.34 I imagine a one-panel cartoon like this being published in The New Yorker.

There is a short speech bubble attached to a scene where two giant robots are standing at the grave of humanity.

“They had a shallower computational structure than we thought.” What a wonderful epitaph.

--- p.55

The most effective way to locate and remove buried mines is to step on them and detonate them.

… …Mark Tilden, a robotics scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, has developed a mine-clearing robot that can do just that.

The autonomous robot, which appeared at the Yuma Proving Ground in Arizona, is about 1.5 meters long and resembles a beetle. According to Tilden, it strode out and performed a landmine removal mission successfully in field tests.

When a buried mine was detected, the robot stepped on it and detonated it, losing one of its legs each time.

However, the robot immediately got up, adjusted its posture, and continued to move forward with its remaining legs, removing mines.

In the end, only one leg remained.

Even in that state, the robot moved forward.

Tilden watched this with excitement.

The machine he created did its job brilliantly.

However, the army colonel who was in charge of the robot's work at the time could not contain his anger and eventually stopped the experiment.

“Why did you stop it? What’s the problem?” Tilden asked.

The colonel could not bear to see the burning and injured machine limping forward, dragging its last remaining leg.

The colonel condemned the experiment as inhumane.

--- p.70

The history of AI is also a history of overly confident predictions.

In August 1955, a group of prominent scholars submitted a grant application to the Rockefeller Foundation for a summer workshop on AI.

What made this document, which was merely a research grant application, famous not only for its historical significance but also because of its grandiose content.

Whenever I think about that application, I often imagine what it would be like if there were similar documents for other historical moments (e.g., 'Activity Summary - Objective: Escape from slavery under the Pharaohs; Items Needed: Means to part the Red Sea; Other: Snacks').

Beginning with this document, AI research embarked on a dialectical current of over-optimism about its goals and a lamenting pessimism about the research's complexity, a trend that continues to this day.

--- p.129

Those who study AI agree that predictions about the timing of the emergence of general AI are not only inconsistent, but also unreliable, as the timing continues to be delayed.

Burner Binge acknowledged this point in his landmark 1993 paper, predicting the timeline.

“I think that within the next 30 years, something more intelligent than humans will emerge (Charles Platt points out that ardent AI advocates have been making the same claim for the past 30 years).

To alleviate the guilt of only suggesting a relatively vague timeframe, let me be a little more specific.

“I would be surprised if AI appeared before 2005 or after 2030.” What the paper stated later became known as Platt’s Law.

That is, those who predict the emergence of general AI always set the emergence date to be approximately 30 years from the predicted time.

Is there a more objective basis for predicting the emergence of general AI?

--- p.154

The possibility of a Skynet that would slaughter and exterminate humanity is not a subject for calm, thoughtful moral reasoning.

However, it should not be dismissed as an entirely absurd claim.

Although the source is unclear, Lincoln is said to have said this:

"The Constitution is not a suicide pact." So, will the issue of AI become a suicide pact for us, one that will lead us to self-destruct? And will the possibility of this self-destruction increase as we recognize AI's personhood, or will it increase as we deny AI's personhood, leading to increasingly powerful AI slaves developing hostility toward humans? Should we halt AI research before we face such a situation? Butler's words come to mind again.

“Wouldn’t it be safer to nip the problem in the bud before it gets any worse and prevent further machine development?” Is there still a chance that the Butlerian Jihad will become a reality?

--- p.196

In fact, I think AI art has the potential to elevate, rather than diminish, the status of human artists in the future, at least in some commercial aspects.

For example, if perfect replicas become easier to obtain, the value of the original may increase.

Another example is that if AI manufacturing methods are developed to produce thousands of identical, perfectly shaped products, products that are imperfect but handcrafted by humans could be certified as "handmade" or "artisan-made" and thus be evaluated as high-quality or authentic, which could actually increase demand.

Perhaps this phenomenon reflects the cost problem of Baumol.

That is, to show off the wealth and status I enjoy, I own products that are produced through expensive and inefficient human labor, rather than cheap and efficient machine-made products.

Millions of replicas only increase the desirability of the original by contrasting them.

Or there may be a growing desire to form a psychological connection with the creator that can never be experienced with mass-produced products.

Perhaps both factors are at play, or perhaps it is a phenomenon reflecting other factors.

Whatever the underlying mechanism, in many fields, claiming a product is human-made will be a viable sales strategy, and a certification mark guaranteeing that the product was entirely handcrafted will enhance its value.

--- p.225

In our society, there are already artificial beings that have been granted legal personality.

In legal terms, persons are divided into natural persons, i.e., human beings who are vulnerable but possess the characteristics of an organic being, and legal entities called legal persons, which are granted some of the rights granted to natural persons.

From the moment the concept of corporate personality first emerged, people realized that there was something strange about the process of forming a corporation.

Just as in science fiction, where one individual is transformed into a completely different being, a group of humans were transformed into a completely new form of immortal artificial beings through a simple written contract.

However, this transformation is not brought about by Dr. Frankenstein in a lightning strike, but through a dry legal provision.

But critics of the concept of corporate personality find the result as horrifying as Frankenstein's monster.

--- p.259

Of course, it is true that we consider such qualities important because we are human, and it is also true that a species-centric perspective is at work here.

If a colony of termites could participate in this conversation (and I personally think the fact that they can't is quite significant here), they would certainly have a different opinion than we do.

But Deval's argument still seems to miss the point.

De Waal tries to convince us by presenting the powerful card of evolutionary science as decisive evidence.

That is, we should value various forms of consciousness based on the entity's potential for survival, rather than on its ability to express reason, ethics, law, love, or beauty.

Of course, the argument of evolutionary science means nothing to a colony of termites.

At least, this is especially true when it is used in an argument rather than simply as a fact.

Because ants don't argue.

But it has important meaning for humans.

--- p.333

If the criterion of species itself is as morally insignificant as the distinction between races, and if appeals to divine omnipotence are ineffective in a pluralistic society, especially within the constitutional framework of a separate state and government, how can we explain and justify the profound aversion so many people feel toward human-nonhuman chimeras? If ethical standards solely focus on abilities, would the specific abilities a chimera possess be morally problematic? For example, if we created a being with human-like abilities, like a chimpanzee, and treated and respected it as such, would such a creative act be acceptable? Does this mean that when judging a creature's personality from such a perspective, we should judge it solely on its actual abilities, regardless of how much human DNA it possesses or its genetic origins?

--- p.401

Imagine philosophers from civilizations on two distant planets.

They each established their own moral philosophy in their own way.

The civilization of the first planet, Ikra, consists of human-like life forms, but unlike other life forms on their planet, they communicate only through telepathy.

Animals on that planet who do not belong to the Ik species have limited ability to sense the emotions of others, and can only communicate through various sounds and gestures.

On the other hand, Ike can communicate telepathically and fluently about fairly complex concepts, emotions, and works of art.

The species that formed a civilization on the second planet is machine intelligence.

Let us call this civilization the Stygians.

According to their records, their 'ancestors', the primitive machines, were created by the hands of living beings and then evolved into their current form.

Just as we humans are fascinated by the primitive humans of the early stages of evolution, the Stygians are also fascinated by the ancient life forms that developed early versions of themselves.

However, from the Stygian perspective, the creature is nothing more than a primitive 'loading program'.

Through this program, actual consciousness was realized, and through its own evolution, the current machine intelligence called Stygian was born.

--- p.415

When we finally achieve general AI, will it truly be conscious, or will it be doomed to be nothing more than a programmed replica? This book presents the most prominent philosophical objections to the notion of machine-based thinking.

This is John Searle's Chinese room thought experiment.

I conclude that while it is possible that Searle's counterargument is true in some specific cases (e.g., one could argue that ChatGPT and Lambda are not conscious), his counterargument is inadequate as a general argument.

If we take his argument at face value, we end up with the disconcerting result of questioning the very possibility of human consciousness.

BF

Skinner said of this problem, “We should not ask whether machines think, but whether humans think.

“The mystery surrounding thinking machines already surrounds thinking humans,” he said.

I disagree with Skinner's conclusion.

But even if we reject that conclusion, we should be humble, not arrogant, about the uniqueness of human consciousness, and we should not be led to a confident, biological exceptionalism that sees humans as uniquely special.

--- p.458

Some companies and developers will focus on developing controllable AI, releasing AI with limited functionality that is no different from a 1980s engineering calculator. Others, for idealistic or practical reasons, will emphasize that their AI systems are not mere products, but rather individuals with personalities.

Therefore, designing AI to appear as a personified being will be a key competitive strategy in this field.

Just as in the field of system development, it is important to choose between free, open source, and proprietary software.

Some may view such a choice as a business strategy, while others may view it as an ethical choice.

So, when advertising this obedient and obedient digital servant, two different promotional strategies will appear: “Open AI: Free AI like free beer!” and “Autonomous AI: AI that is autonomous like a human!”

And one day, you might see the phrase “Recipes provided by ethically developed, autonomous, conscious AI” on supermarket product ads.

The more I think about it, the more I sigh.

--- p.517

Publisher's Review

An era where AI writes poetry, provides legal advice, and even writes news articles.

How far can we call ourselves human?

AI is no longer just a tool.

They use language skills that were once considered a unique privilege of humans, imitate creation, and even induce empathy.

We are no longer the only beings who can fluently produce language and ideas.

So, can we truly say that AI possesses consciousness? Or is it merely a sophisticated imitation of humans? If the claim that AI possesses consciousness becomes increasingly convincing, how will our world change?

Does this still sound like a story from the distant future?

The future is much closer than we think.

Legal scholar James Boyle, a professor at Duke University Law School and a pioneer in digital rights, traces the boundaries of "personality" across AI, humans, corporations, animals, and even chimeras, asking how far we should go to accept them as human. What if AI were to stand trial? Could robots with emotions have rights?

"Does AI Dream of Humanity" tenaciously delves into the boundary between "human" and "non-human."

What makes humans human? And are only humans entitled to legal rights? Until now, we have granted rights based on "species."

But that standard is being shaken as AI begins to create language, appear to think, and assert its own existence.

Author James Boyle, a legal scholar and pioneer of public intellectual property, this time piques readers' curiosity with the somewhat abstract but existential topic of 'personality.'

Through a thrilling journey that blends law and philosophy, science and science fiction, ethics and popular culture, we explore how our future with AI will unfold.

This book traces how and to whom we have attributed "personality" throughout history, from corporations and animals to brain-dead patients, genetically engineered organisms, chimeras, embryos, and AI, and analyzes how our society has drawn its boundaries.

And then he asks:

"If there are beings who speak, feel, and think like humans, are they truly human? Should they be granted human rights?" The answer to this question becomes even more urgent as we face artificial intelligence, human-animal hybrids, and even nonhuman entities like corporations.

To what kind of beings should we grant legal rights, social consideration, and moral dignity?

James Boyle uses hypothetical cases to illuminate issues that might otherwise be perceived abstractly.

Hal, a highly evolved artificial intelligence, can understand humor and appreciate art, but it can be turned off with a single power button.

Chimpy, a creature created by combining chimpanzee and human genes, understands some human emotions, but is still legally considered an animal.

Some say, "Hal is just a smart toaster," while others say, "Chimpi can never be human."

But are these standards truly justified? And how long will they remain valid?

The book is divided into five chapters, covering non-human entities that are distinct from humans but also controversial enough to warrant discussion, including artificial intelligence (AI), corporations with legal personality, animals asserting their rights, and genetically engineered organisms and hybrids.

We have already granted legal personality to non-human entities such as corporations, and have claimed 'freedom' for certain animals through lawsuits.

However, the boundaries of personality have been vaguely drawn for beings who are human but unable to express themselves, such as patients with severe brain damage, fetuses, and elderly dementia patients.

The author points out how much empathy influences our judgment of character, saying, “Our empathy is sometimes excessive, causing us to feel emotions towards robots or machines, and sometimes severely inadequate, causing us to exclude animals or the disabled.”

According to him, judgments about personality, whether AI, animals, or humans, are not a matter of pure reason, but rather a complex ensemble of judgments intertwined with history, culture, emotions, and politics.

This book offers readers a profound and lucid reflection on the most philosophical and political questions posed by the future. It is highly recommended for science fiction fans, readers interested in artificial intelligence, and anyone interested in philosophy and ethics.

To whom will we attribute personhood? This question will become both philosophical and legal, and will increasingly become a practical issue.

How far can we call ourselves human?

AI is no longer just a tool.

They use language skills that were once considered a unique privilege of humans, imitate creation, and even induce empathy.

We are no longer the only beings who can fluently produce language and ideas.

So, can we truly say that AI possesses consciousness? Or is it merely a sophisticated imitation of humans? If the claim that AI possesses consciousness becomes increasingly convincing, how will our world change?

Does this still sound like a story from the distant future?

The future is much closer than we think.

Legal scholar James Boyle, a professor at Duke University Law School and a pioneer in digital rights, traces the boundaries of "personality" across AI, humans, corporations, animals, and even chimeras, asking how far we should go to accept them as human. What if AI were to stand trial? Could robots with emotions have rights?

"Does AI Dream of Humanity" tenaciously delves into the boundary between "human" and "non-human."

What makes humans human? And are only humans entitled to legal rights? Until now, we have granted rights based on "species."

But that standard is being shaken as AI begins to create language, appear to think, and assert its own existence.

Author James Boyle, a legal scholar and pioneer of public intellectual property, this time piques readers' curiosity with the somewhat abstract but existential topic of 'personality.'

Through a thrilling journey that blends law and philosophy, science and science fiction, ethics and popular culture, we explore how our future with AI will unfold.

This book traces how and to whom we have attributed "personality" throughout history, from corporations and animals to brain-dead patients, genetically engineered organisms, chimeras, embryos, and AI, and analyzes how our society has drawn its boundaries.

And then he asks:

"If there are beings who speak, feel, and think like humans, are they truly human? Should they be granted human rights?" The answer to this question becomes even more urgent as we face artificial intelligence, human-animal hybrids, and even nonhuman entities like corporations.

To what kind of beings should we grant legal rights, social consideration, and moral dignity?

James Boyle uses hypothetical cases to illuminate issues that might otherwise be perceived abstractly.

Hal, a highly evolved artificial intelligence, can understand humor and appreciate art, but it can be turned off with a single power button.

Chimpy, a creature created by combining chimpanzee and human genes, understands some human emotions, but is still legally considered an animal.

Some say, "Hal is just a smart toaster," while others say, "Chimpi can never be human."

But are these standards truly justified? And how long will they remain valid?

The book is divided into five chapters, covering non-human entities that are distinct from humans but also controversial enough to warrant discussion, including artificial intelligence (AI), corporations with legal personality, animals asserting their rights, and genetically engineered organisms and hybrids.

We have already granted legal personality to non-human entities such as corporations, and have claimed 'freedom' for certain animals through lawsuits.

However, the boundaries of personality have been vaguely drawn for beings who are human but unable to express themselves, such as patients with severe brain damage, fetuses, and elderly dementia patients.

The author points out how much empathy influences our judgment of character, saying, “Our empathy is sometimes excessive, causing us to feel emotions towards robots or machines, and sometimes severely inadequate, causing us to exclude animals or the disabled.”

According to him, judgments about personality, whether AI, animals, or humans, are not a matter of pure reason, but rather a complex ensemble of judgments intertwined with history, culture, emotions, and politics.

This book offers readers a profound and lucid reflection on the most philosophical and political questions posed by the future. It is highly recommended for science fiction fans, readers interested in artificial intelligence, and anyone interested in philosophy and ethics.

To whom will we attribute personhood? This question will become both philosophical and legal, and will increasingly become a practical issue.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 27, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 576 pages | 826g | 152*225*28mm

- ISBN13: 9791193638873

- ISBN10: 1193638879

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)