Where does the greatest wealth come from?

|

Description

Book Introduction

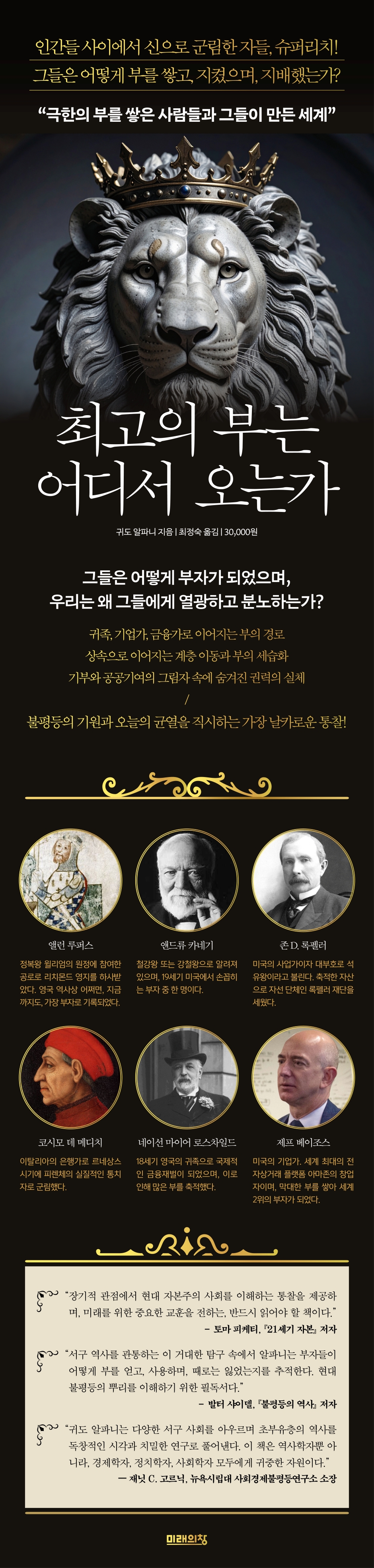

Those who reign as gods among humans, the super rich!

How did they accumulate, maintain, and rule their wealth?

Throughout thousands of years of history, the rich have always been the objects of admiration, ire, and concern.

In the midst of epidemics, famine, wars, and financial crises, some people have fallen, while others have become rich.

The super-rich are not just rich people with a lot of money.

They led the times, created institutions, and often possessed more resources than the nation.

From medieval kings and nobles to modern merchants and financiers, to contemporary tech moguls, it traces the rise and evolution of the super-rich over thousands of years and their complex relationships with society.

This book is not a simple biography of the rich, listing billionaires from a certain era.

Rather, Alfani asks the question, “Who became rich?” to penetrate the economic and social structures of each era and reveal how the sources of wealth have changed.

"Where the Greatest Wealth Comes from" has received praise from influential media outlets such as the Financial Times, the New Yorker, and the New Statesman, and has been strongly recommended by world-renowned scholars such as Thomas Piketty, Walter Scheidel, and Branko Milanovic.

From ancient Rome to the Medici and Jeff Bezos,

The story of the rich who became gods among humans

How did they accumulate, maintain, and rule their wealth?

Throughout thousands of years of history, the rich have always been the objects of admiration, ire, and concern.

In the midst of epidemics, famine, wars, and financial crises, some people have fallen, while others have become rich.

The super-rich are not just rich people with a lot of money.

They led the times, created institutions, and often possessed more resources than the nation.

From medieval kings and nobles to modern merchants and financiers, to contemporary tech moguls, it traces the rise and evolution of the super-rich over thousands of years and their complex relationships with society.

This book is not a simple biography of the rich, listing billionaires from a certain era.

Rather, Alfani asks the question, “Who became rich?” to penetrate the economic and social structures of each era and reveal how the sources of wealth have changed.

"Where the Greatest Wealth Comes from" has received praise from influential media outlets such as the Financial Times, the New Yorker, and the New Statesman, and has been strongly recommended by world-renowned scholars such as Thomas Piketty, Walter Scheidel, and Branko Milanovic.

From ancient Rome to the Medici and Jeff Bezos,

The story of the rich who became gods among humans

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

Part 1: Wealth in the Hands of a Few

Chapter 1: What is wealth, and how much does it take to be considered rich?

Chapter 2: Concentration of Wealth and the Size of the Wealthy

Part 2: The Road to Riches

Chapter 3: The Heirs of Wealth: The Rise of a New Nobility

Chapter 4: New Drivers of Wealth: Innovation and Technology

Chapter 5: The Shortcut to Riches: Finance

Chapter 6: The Rich Man's Dilemma: Saving and Spending

Chapter 7 Towards the Peak of Wealth

Part 3: The Social Role of the Rich

Chapter 8: Why Wealth Concentration Becomes a Social Problem

Chapter 9: Sponsors, Philanthropists, and Donors

Chapter 10: The Ultra-Wealthy and Politics

Chapter 11: The Age of Crisis and the Wealthy: From the Black Death to COVID-19

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

main

Sources and References for the Chart

Part 1: Wealth in the Hands of a Few

Chapter 1: What is wealth, and how much does it take to be considered rich?

Chapter 2: Concentration of Wealth and the Size of the Wealthy

Part 2: The Road to Riches

Chapter 3: The Heirs of Wealth: The Rise of a New Nobility

Chapter 4: New Drivers of Wealth: Innovation and Technology

Chapter 5: The Shortcut to Riches: Finance

Chapter 6: The Rich Man's Dilemma: Saving and Spending

Chapter 7 Towards the Peak of Wealth

Part 3: The Social Role of the Rich

Chapter 8: Why Wealth Concentration Becomes a Social Problem

Chapter 9: Sponsors, Philanthropists, and Donors

Chapter 10: The Ultra-Wealthy and Politics

Chapter 11: The Age of Crisis and the Wealthy: From the Black Death to COVID-19

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

main

Sources and References for the Chart

Detailed image

Into the book

This book is not simply about the lives and actions of the rich or ultra-rich, nor is it swayed by my personal fascination or aversion to them.

It's simply an attempt to look at the overall history of the wealthy throughout the ages.

Many real-life examples will be presented, and brief anecdotes from the lives of some notable individuals will be included, which are not only informative and helpful for scientific explanation, but also quite entertaining.

Additionally, the examples discussed in this book will be presented together with a comprehensive and systematic discussion.

--- p.5

So to speak, it is like this.

Let's take the example of artificial lighting or voice recording.

If Julius Caesar wanted to read all night, roam the palace at night, and listen to his favorite songs, he would have needed hundreds of workers (slaves) to hold torches all night or sing his favorite arias.

If he had done that every night, even Caesar would have been destitute soon (or perhaps the slaves would have risen up).

But today, the cost of such entertainment is very small, even trivial (as little as $2 a night).

As a result, some conclude that Caesar's wealth must have been very small by today's material standards.

It is clear that people in Caesar's time had much less than people today, and the world today is incomparably richer than it was before.

--- p.31

Observing and measuring ancient inequalities became somewhat easier after classical antiquity.

The concentration of wealth in the Roman territories appears to have increased steadily from the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD, during which time the size of the highest fortunes increased 80-fold, from 4 to 5 million sesterces (a coin used in ancient Rome - translator's note) to 300 to 400 million sesterces.

During the reign of Emperor Nero (reigned 54–68 AD), six men are said to have owned roughly half of the African province corresponding to present-day Tunisia and the coast of Libya (at least until the emperor confiscated their property).

The richest man of his time was probably Marcus Antonius Pallas, a Greek slave.

He rose to the highest office in the imperial government, serving as chancellor of finance under the emperors Claudius and Nero.

According to the Roman historian Tacitus, Pallas' personal wealth was 300 million sesterces, which was more than the 250 million sesterces owned by the imperial family at the time of Emperor Augustus.

And he is thought to have been wealthier than Nero himself, until Nero ordered Pallas poisoned and most of his wealth confiscated.

And Marcus Licinius Crassus, who was known to be extremely wealthy at the end of the Republic, had a fortune of 200 million sesterces.

In 60 BC, he joined forces with Julius Caesar and Gnaeus Pompey to form the First Triumvirate, seeking to leverage his vast wealth to gain political advantage.

It is estimated that the annual income from Crassus's estate could have supported 32,000 Romans.

--- p.54

The culmination of Allen's rise was the grant of the Richmond Estate, which included over 199 estates.

Alan immediately began building Richmond Castle in a strategic and easily defensible location, which became a landmark symbolizing Alan's domain.

His estates continued to grow, largely due to Alan's ability to side early on with the victors in the frequent rebellions against William and his successor, William II.

By the 1080s, Alan Rufus was undoubtedly one of the wealthiest men in England.

Although the information is essentially limited, it is only for reference purposes, and estimates suggest that the income from his vast lands amounted to around 7.3% of England's total net income at the time, making Alan probably the richest person ever to have lived in Britain (monarchs are not usually included in such rankings).

Significantly, several of William the Conqueror's early companions still appear in recent lists of the richest people in British history.

--- p.93

When the British aristocracy was in decline, they often chose to marry wealthy commoners, including foreigners, to solve their financial problems.

This trend was particularly pronounced in the 1880s, when falling agricultural prices and relatively high labor costs combined to push large estate owners into bankruptcy.

In such circumstances, marrying a commoner seemed like a better alternative than selling off land or a valuable art collection.

An indicator of this is the proportion of women of commoner origin introduced to the court, which increased from about 10% in 1841 to over 50% by the end of the century.

Many of them were daughters of wealthy American industrialists.

--- p.106

This new situation has opened up new avenues for wealth for those bold enough to take economic or personal risks.

Consider, for example, Jan Pieterszoon Kuhn, a Dutch merchant born in 1587 in the port city of Hoorn in the northern Netherlands to a relatively ordinary family.

His father, who started out as a brewer and later moved into commerce, seemed to understand that a new golden age of trade was dawning.

He sent his son to Rome to be apprenticed for seven years by the Vicious family, a Flemish-Italian family.

There, Kuhn learned the accounting and trading techniques used in Southern Europe, especially double-entry bookkeeping, which was more advanced than in Northern Europe at the time.

Back in the Netherlands, Kuhn was ready to join the VOC's ambitious expedition to the East Indies, and he joined as an assistant merchant in 1607.

To appreciate the personal risk Kuhn was taking, consider that the mortality rate among those who left the Netherlands for the early VOC-organized expeditions to the East Indies was (by one estimate) nearly 50%.

However, Kuhn's first voyage was a success, and by 1612 he was ready to embark on a second voyage as a senior merchant.

--- p.135

Andrew Carnegie was the son of a poor weaver from Scotland who immigrated to the United States with his family in 1848.

His first job was in a factory in Pittsburgh, where he was paid $1.20 a week.

However, in 1901, when he sold his stake in the steel industry to the newly founded U.S. Steel, he received $225.6 million (about $7.1 billion in 2020 dollars) in gold bonds.

He was the richest man in America and probably the richest man in the world.

Carnegie was a very unusual person.

He did not hesitate to exploit the company's employees.

In his steel mill, 12-hour workdays were the norm, with Sundays being a day off after every other 24-hour shift.

He also did not hesitate to use violence and intimidation against unions and to evade government regulations.

He even developed a theory drawn from social Darwinism to justify his predatory behavior.

Carnegie paid special tribute to the American philosopher, sociologist, and biologist Herbert Spencer.

But in his later years he transformed into a great philanthropist, and in his 1889 book The Gospel of Wealth he argued that the only worthwhile act a rich person could perform was to give away his life's savings.

--- p.157

Let me tell you what I heard.

A lot of people tell me this.

“Francesco di Marco is giving up his reputation as Florence’s greatest merchant to become a money changer.

And there is not a single money changer who does not engage in usury.” I said in your defense that you are trying to be more faithful as a merchant than ever before, and that even if you open a bank, it will not be for usury.

Then he said this again.

“People won’t think that way.

“I’ll call him a moneylender!” So I said again.

“He’s not trying to be a moneylender.

“I will leave all my wealth to the poor.” But they still said this.

“Don’t expect him to be treated like a great merchant again or to maintain his good reputation.”

--- p.181

Throughout history, the rich have been subjected to conflicting assessments: on the one hand, they have been accused of being pathologically greedy, and on the other, they have been criticized for squandering their wealth in pursuit of pleasure and vanity.

Because the wealthy have exhibited unusual behaviors in both saving and spending, it is worthwhile to closely examine their collective behavior.

In the long run, the key to wealth accumulation was saving rather than spending.

Given that wealth can be inherited through generations, those with a strong tendency to save are more likely to build a family than those with a tendency to spend.

This seems more likely to entrench extreme wealth inequality in society, requiring no special qualities other than stinginess.

As we have seen, medieval society condemned stinginess, but at the same time, extravagant displays of wealth were also condemned.

In fact, waste was considered as great a sin as being stingy.

So the question of whether to encourage saving or not has always been a difficult one for Western societies when dealing with the extremely wealthy, especially the ultra-wealthy.

--- p.234

Since prehistoric times, the possibility of inheriting wealth has played a significant role in determining whether a society will experience relatively high levels of economic inequality.

It has been argued that the actual level of economic inequality in small-scale societies, past and present, including hunter-gatherer societies and all early agricultural societies since the Neolithic agricultural revolution, is largely determined by the typical form of wealth in that society.

Pastoral and agricultural societies, where material wealth was paramount, experienced much greater inequality than hunter-gatherer societies, where individual abilities and relationships were the primary source of wealth.

Even if we look at the Gini coefficient, which indicates inequality of material wealth, the average for agricultural societies is 0.57, while that for hunter-gatherer societies is only 0.36.

A key factor that explains the differences between these societies, which all share the same basic need for survival, is the extent to which each society's typical wealth is inheritable.

Material wealth is inherently easier to pass on than personal abilities or relational wealth, and land and livestock are better suited to intergenerational transfer than the consumable and temporary household goods of hunter-gatherer societies.

In agricultural and pastoral societies, the accumulation of wealth is further promoted as the size of livestock herds, irrigated farms, etc. increases, as profits increase.

--- p.284

There are growing concerns that for some of today's wealthy and ultra-wealthy, giving is merely a means of avoiding taxes, allowing them to retain de facto control over the assets they "donate" while simultaneously taking advantage of tax breaks.

Of course, this is certainly not the only motivation for sponsors, and historically, it is clear that large-scale sponsorship can exist without tax breaks.

Even in the Middle Ages and early modern times, patronage could provide some economic benefits; for example, the Dukes of Milan in the 14th century granted tax exemptions to some charities.

But the situation in the 19th century was very different.

The best-studied case is the United States, where, despite the substantial scale of sponsorship and donations in the early 20th century, individuals and corporations did not receive tax benefits for their donations.

In fact, the estate tax at the time imposed a heavier tax on bequests to "non-relatives," including charities, than on bequests to relatives, and it was not until 1917 that American citizens were able to deduct donations from their taxable income.

Since then, the relative magnitude of donations has been inversely proportional to the top income tax rate, suggesting that at some point tax avoidance became a significant motivation for donors, making it difficult to classify them as philanthropists any longer.

While long-term giving trends in European countries are less well known, recent research from the OECD suggests that the overall tax structure of Western countries today is broadly similar, and concerns about tax avoidance or even evasion are similar.

--- p.366

Like Silvio Berlusconi, Donald Trump is seen as a successful businessman who "took on the state."

And like Berlusconi, he has been accused of a number of economic and political crimes, as well as a problematic private life.

But what we should note is that Trump's vast wealth and media connections undoubtedly helped his political rise.

To this, one might counter that in the American political system, political donations from supporters are ultimately more important than individual wealth.

This leads to another problem, namely, the problem of politicians who, even if they are not ultra-wealthy themselves, receive support from the ultra-wealthy or who in some way rely on their support.

--- p.396

The Great Recession of 2008-2009, which triggered a sovereign debt crisis in some countries that lasted until 2013, left many people with a perception that the wealthy were indifferent and insensitive to society's suffering.

Even as they were blamed for causing the crisis with their greedy behavior, the top 1% appeared to be collectively rejecting the traditional role of the wealthy in alleviating the damage with their private resources.

Such criticism has been reignited by the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and public health policies implemented to curb the infection.

Of course, this time, few, except for die-hard conspiracy theorists, blamed the wealthy for the crisis.

However, in some countries, criticism has been raised that pre-crisis policies, such as the privatization of public health services, were problematic.

Privatization benefits only the wealthy and weakens society's ability to respond to the pandemic.

But another criticism—that the wealthy haven't been willing to shoulder the costs of finding solutions—is exactly the same as the one raised during the Great Recession.

It's simply an attempt to look at the overall history of the wealthy throughout the ages.

Many real-life examples will be presented, and brief anecdotes from the lives of some notable individuals will be included, which are not only informative and helpful for scientific explanation, but also quite entertaining.

Additionally, the examples discussed in this book will be presented together with a comprehensive and systematic discussion.

--- p.5

So to speak, it is like this.

Let's take the example of artificial lighting or voice recording.

If Julius Caesar wanted to read all night, roam the palace at night, and listen to his favorite songs, he would have needed hundreds of workers (slaves) to hold torches all night or sing his favorite arias.

If he had done that every night, even Caesar would have been destitute soon (or perhaps the slaves would have risen up).

But today, the cost of such entertainment is very small, even trivial (as little as $2 a night).

As a result, some conclude that Caesar's wealth must have been very small by today's material standards.

It is clear that people in Caesar's time had much less than people today, and the world today is incomparably richer than it was before.

--- p.31

Observing and measuring ancient inequalities became somewhat easier after classical antiquity.

The concentration of wealth in the Roman territories appears to have increased steadily from the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD, during which time the size of the highest fortunes increased 80-fold, from 4 to 5 million sesterces (a coin used in ancient Rome - translator's note) to 300 to 400 million sesterces.

During the reign of Emperor Nero (reigned 54–68 AD), six men are said to have owned roughly half of the African province corresponding to present-day Tunisia and the coast of Libya (at least until the emperor confiscated their property).

The richest man of his time was probably Marcus Antonius Pallas, a Greek slave.

He rose to the highest office in the imperial government, serving as chancellor of finance under the emperors Claudius and Nero.

According to the Roman historian Tacitus, Pallas' personal wealth was 300 million sesterces, which was more than the 250 million sesterces owned by the imperial family at the time of Emperor Augustus.

And he is thought to have been wealthier than Nero himself, until Nero ordered Pallas poisoned and most of his wealth confiscated.

And Marcus Licinius Crassus, who was known to be extremely wealthy at the end of the Republic, had a fortune of 200 million sesterces.

In 60 BC, he joined forces with Julius Caesar and Gnaeus Pompey to form the First Triumvirate, seeking to leverage his vast wealth to gain political advantage.

It is estimated that the annual income from Crassus's estate could have supported 32,000 Romans.

--- p.54

The culmination of Allen's rise was the grant of the Richmond Estate, which included over 199 estates.

Alan immediately began building Richmond Castle in a strategic and easily defensible location, which became a landmark symbolizing Alan's domain.

His estates continued to grow, largely due to Alan's ability to side early on with the victors in the frequent rebellions against William and his successor, William II.

By the 1080s, Alan Rufus was undoubtedly one of the wealthiest men in England.

Although the information is essentially limited, it is only for reference purposes, and estimates suggest that the income from his vast lands amounted to around 7.3% of England's total net income at the time, making Alan probably the richest person ever to have lived in Britain (monarchs are not usually included in such rankings).

Significantly, several of William the Conqueror's early companions still appear in recent lists of the richest people in British history.

--- p.93

When the British aristocracy was in decline, they often chose to marry wealthy commoners, including foreigners, to solve their financial problems.

This trend was particularly pronounced in the 1880s, when falling agricultural prices and relatively high labor costs combined to push large estate owners into bankruptcy.

In such circumstances, marrying a commoner seemed like a better alternative than selling off land or a valuable art collection.

An indicator of this is the proportion of women of commoner origin introduced to the court, which increased from about 10% in 1841 to over 50% by the end of the century.

Many of them were daughters of wealthy American industrialists.

--- p.106

This new situation has opened up new avenues for wealth for those bold enough to take economic or personal risks.

Consider, for example, Jan Pieterszoon Kuhn, a Dutch merchant born in 1587 in the port city of Hoorn in the northern Netherlands to a relatively ordinary family.

His father, who started out as a brewer and later moved into commerce, seemed to understand that a new golden age of trade was dawning.

He sent his son to Rome to be apprenticed for seven years by the Vicious family, a Flemish-Italian family.

There, Kuhn learned the accounting and trading techniques used in Southern Europe, especially double-entry bookkeeping, which was more advanced than in Northern Europe at the time.

Back in the Netherlands, Kuhn was ready to join the VOC's ambitious expedition to the East Indies, and he joined as an assistant merchant in 1607.

To appreciate the personal risk Kuhn was taking, consider that the mortality rate among those who left the Netherlands for the early VOC-organized expeditions to the East Indies was (by one estimate) nearly 50%.

However, Kuhn's first voyage was a success, and by 1612 he was ready to embark on a second voyage as a senior merchant.

--- p.135

Andrew Carnegie was the son of a poor weaver from Scotland who immigrated to the United States with his family in 1848.

His first job was in a factory in Pittsburgh, where he was paid $1.20 a week.

However, in 1901, when he sold his stake in the steel industry to the newly founded U.S. Steel, he received $225.6 million (about $7.1 billion in 2020 dollars) in gold bonds.

He was the richest man in America and probably the richest man in the world.

Carnegie was a very unusual person.

He did not hesitate to exploit the company's employees.

In his steel mill, 12-hour workdays were the norm, with Sundays being a day off after every other 24-hour shift.

He also did not hesitate to use violence and intimidation against unions and to evade government regulations.

He even developed a theory drawn from social Darwinism to justify his predatory behavior.

Carnegie paid special tribute to the American philosopher, sociologist, and biologist Herbert Spencer.

But in his later years he transformed into a great philanthropist, and in his 1889 book The Gospel of Wealth he argued that the only worthwhile act a rich person could perform was to give away his life's savings.

--- p.157

Let me tell you what I heard.

A lot of people tell me this.

“Francesco di Marco is giving up his reputation as Florence’s greatest merchant to become a money changer.

And there is not a single money changer who does not engage in usury.” I said in your defense that you are trying to be more faithful as a merchant than ever before, and that even if you open a bank, it will not be for usury.

Then he said this again.

“People won’t think that way.

“I’ll call him a moneylender!” So I said again.

“He’s not trying to be a moneylender.

“I will leave all my wealth to the poor.” But they still said this.

“Don’t expect him to be treated like a great merchant again or to maintain his good reputation.”

--- p.181

Throughout history, the rich have been subjected to conflicting assessments: on the one hand, they have been accused of being pathologically greedy, and on the other, they have been criticized for squandering their wealth in pursuit of pleasure and vanity.

Because the wealthy have exhibited unusual behaviors in both saving and spending, it is worthwhile to closely examine their collective behavior.

In the long run, the key to wealth accumulation was saving rather than spending.

Given that wealth can be inherited through generations, those with a strong tendency to save are more likely to build a family than those with a tendency to spend.

This seems more likely to entrench extreme wealth inequality in society, requiring no special qualities other than stinginess.

As we have seen, medieval society condemned stinginess, but at the same time, extravagant displays of wealth were also condemned.

In fact, waste was considered as great a sin as being stingy.

So the question of whether to encourage saving or not has always been a difficult one for Western societies when dealing with the extremely wealthy, especially the ultra-wealthy.

--- p.234

Since prehistoric times, the possibility of inheriting wealth has played a significant role in determining whether a society will experience relatively high levels of economic inequality.

It has been argued that the actual level of economic inequality in small-scale societies, past and present, including hunter-gatherer societies and all early agricultural societies since the Neolithic agricultural revolution, is largely determined by the typical form of wealth in that society.

Pastoral and agricultural societies, where material wealth was paramount, experienced much greater inequality than hunter-gatherer societies, where individual abilities and relationships were the primary source of wealth.

Even if we look at the Gini coefficient, which indicates inequality of material wealth, the average for agricultural societies is 0.57, while that for hunter-gatherer societies is only 0.36.

A key factor that explains the differences between these societies, which all share the same basic need for survival, is the extent to which each society's typical wealth is inheritable.

Material wealth is inherently easier to pass on than personal abilities or relational wealth, and land and livestock are better suited to intergenerational transfer than the consumable and temporary household goods of hunter-gatherer societies.

In agricultural and pastoral societies, the accumulation of wealth is further promoted as the size of livestock herds, irrigated farms, etc. increases, as profits increase.

--- p.284

There are growing concerns that for some of today's wealthy and ultra-wealthy, giving is merely a means of avoiding taxes, allowing them to retain de facto control over the assets they "donate" while simultaneously taking advantage of tax breaks.

Of course, this is certainly not the only motivation for sponsors, and historically, it is clear that large-scale sponsorship can exist without tax breaks.

Even in the Middle Ages and early modern times, patronage could provide some economic benefits; for example, the Dukes of Milan in the 14th century granted tax exemptions to some charities.

But the situation in the 19th century was very different.

The best-studied case is the United States, where, despite the substantial scale of sponsorship and donations in the early 20th century, individuals and corporations did not receive tax benefits for their donations.

In fact, the estate tax at the time imposed a heavier tax on bequests to "non-relatives," including charities, than on bequests to relatives, and it was not until 1917 that American citizens were able to deduct donations from their taxable income.

Since then, the relative magnitude of donations has been inversely proportional to the top income tax rate, suggesting that at some point tax avoidance became a significant motivation for donors, making it difficult to classify them as philanthropists any longer.

While long-term giving trends in European countries are less well known, recent research from the OECD suggests that the overall tax structure of Western countries today is broadly similar, and concerns about tax avoidance or even evasion are similar.

--- p.366

Like Silvio Berlusconi, Donald Trump is seen as a successful businessman who "took on the state."

And like Berlusconi, he has been accused of a number of economic and political crimes, as well as a problematic private life.

But what we should note is that Trump's vast wealth and media connections undoubtedly helped his political rise.

To this, one might counter that in the American political system, political donations from supporters are ultimately more important than individual wealth.

This leads to another problem, namely, the problem of politicians who, even if they are not ultra-wealthy themselves, receive support from the ultra-wealthy or who in some way rely on their support.

--- p.396

The Great Recession of 2008-2009, which triggered a sovereign debt crisis in some countries that lasted until 2013, left many people with a perception that the wealthy were indifferent and insensitive to society's suffering.

Even as they were blamed for causing the crisis with their greedy behavior, the top 1% appeared to be collectively rejecting the traditional role of the wealthy in alleviating the damage with their private resources.

Such criticism has been reignited by the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and public health policies implemented to curb the infection.

Of course, this time, few, except for die-hard conspiracy theorists, blamed the wealthy for the crisis.

However, in some countries, criticism has been raised that pre-crisis policies, such as the privatization of public health services, were problematic.

Privatization benefits only the wealthy and weakens society's ability to respond to the pandemic.

But another criticism—that the wealthy haven't been willing to shoulder the costs of finding solutions—is exactly the same as the one raised during the Great Recession.

--- p.456

Publisher's Review

People who amassed extreme wealth and the world they created

How did they become rich,

Why are we so excited and angry about them?

Today's world is experiencing extreme concentration of wealth, to the point where it could be called a "second golden age."

With the top 1% now owning nearly half of the world's wealth, the super-rich are capturing the world's attention by boldly displaying their wealth.

Jeff Bezos's extravagant wedding in Venice, Italy, sparked a polarizing debate, but historically, it's nothing new.

The nobles of the Middle Ages and Renaissance also flaunted their prestige with extravagant weddings, luxuries, and lavish buildings that defied common sense, and this display served as a means of justifying their 'social status'.

Super Rich, Who Are They?

"Where the Best Wealth Comes from" is not simply a story about the rich or a list of economic indicators.

Economic historian Guido Alfani doggedly traces how the rich emerged, how they acquired the "right to be rich," and how they inherited and legitimized their wealth across thousands of years of Western history.

From medieval kings and nobles, to Renaissance merchants and financiers, to industrial capitalists, to modern-day tech billionaires, the rich have not simply accumulated wealth; they have led their times, shaped institutions, and often possessed more resources than nations.

In Roman times, six rich men are said to have owned about half of Africa, and Marcus Antonius Pallas had more wealth than the then emperor Nero.

In the 11th century, the lands of Alan the Red, an English nobleman considered one of the richest men of his time, accounted for approximately 7.3% of England's total net income at the time.

Jay Gould, in the 19th century, controlled 15% of the U.S. railroads, and Jeff Bezos, the richest man of the 21st century, has amassed enough wealth from March to August 2020 alone to pay each of Amazon's 876,000 employees a $100,000 bonus.

While wealth has always been concentrated, the degree of that concentration has grown exponentially since the Industrial Revolution, and has reached its peak once again in the 21st century.

According to "Where Does the Greatest Wealth Come From?", until the mid-19th century, many of Europe's super-rich were of noble birth, and in the 20th century, self-made millionaires who made their fortunes through commerce and finance emerged.

But in recent decades, the share of wealthy people passing down their wealth through inheritance has been rising again, and the concentration of wealth in the top 0.1% has surpassed levels seen just before the Great Depression in 1929.

Inequality that doesn't disappear: "What do we expect from the rich, and what are we disappointed about?"

With the exception of the Black Death and the World Wars, wealth inequality has steadily increased over the centuries.

Europe temporarily became more equal after the Black Death in the 14th century, but inequality began to increase again from the 15th century.

Especially with the rise of finance during the Industrial Revolution, entrepreneurs and financiers replaced the aristocrats of the past as the new super-rich.

They have grown beyond being simply 'rich' to become entities that move institutions and power.

The United States, on the other hand, started somewhat differently.

In the absence of aristocracy and hereditary privilege, America in its early years was a relatively egalitarian society.

However, industrialization, the development of railroads, and the rapid development of the financial system since the mid-19th century accelerated wealth inequality.

Today, the United States produces more than half of the world's super-rich and is considered one of the most unequal countries.

Concentration of wealth is no longer just a story of the aristocracy of the past.

This is the reality that is happening right before our eyes.

"Where Does the Greatest Wealth Come From?" traces the historical flow and concentration of wealth, and analyzes in detail the birth and changes of the wealthy in each era, as well as the complex positions they have held in society, from the traditional super-rich who formed "families" like the Rothschilds, Fuggers, and Medicis, to modern-day tech billionaires like Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and Jeff Bezos.

Alfani systematically tells this story, crossing data and statistics, philosophy and politics, individuals and institutions, illuminating not simply the actions of wealthy individuals but the origins of the social structure of "wealth."

Consumption is luxury, saving is accumulation?! The dilemma of the super-rich.

In the past, the rich were always the objects of suspicion and criticism in Western society.

Medieval monks considered the rich to be sinners, and those who pursued private gain over the public good were subject to banishment.

But when social crises such as epidemics, wars, and crop failures struck, the rich took on the role of 'saviors.'

By donating, paying taxes, building infrastructure, and providing loans, they contributed to the community, thereby gaining legitimacy and social trust.

But what about today? They've managed to preserve their wealth through pandemics and global financial crises, but they're shirking their responsibility to the community.

Alfani says:

“Historically, when the rich fail to contribute to society, and when they are seen or suspected of being insensitive to the suffering of the masses and exploiting that suffering for profit, society becomes unstable, leading to riots and uprisings.” Even temporary tax increases are seen as a “war on the rich,” and they have reached the point where they are instead using public taxes to cover their own losses.

Asking the rich why they exist

If in the past the wealthy secured legitimacy by functioning as a "responsible class," today we may be witnessing the collapse of that legitimacy.

Saying, “I would rather donate than pay taxes” is not just an empty declaration.

As in the past, the rich still seek to gain the moral high ground by donating and avoiding taxes.

The author sharply examines the historical debate between "good faith" and "duty," revealing the underlying logic of power and the shifting social contract.

This book is not just a history book that illuminates the past, but also a warning for the future.

"Where Does the Greatest Wealth Come From?" explores the history of power, legitimacy, and responsibility of the super-rich, spanning past and present.

And he asks us:

Do today's wealthy truly deserve to exist? What should we do when the world is ruled by wealthy people who no longer contribute to society?

How did they become rich,

Why are we so excited and angry about them?

Today's world is experiencing extreme concentration of wealth, to the point where it could be called a "second golden age."

With the top 1% now owning nearly half of the world's wealth, the super-rich are capturing the world's attention by boldly displaying their wealth.

Jeff Bezos's extravagant wedding in Venice, Italy, sparked a polarizing debate, but historically, it's nothing new.

The nobles of the Middle Ages and Renaissance also flaunted their prestige with extravagant weddings, luxuries, and lavish buildings that defied common sense, and this display served as a means of justifying their 'social status'.

Super Rich, Who Are They?

"Where the Best Wealth Comes from" is not simply a story about the rich or a list of economic indicators.

Economic historian Guido Alfani doggedly traces how the rich emerged, how they acquired the "right to be rich," and how they inherited and legitimized their wealth across thousands of years of Western history.

From medieval kings and nobles, to Renaissance merchants and financiers, to industrial capitalists, to modern-day tech billionaires, the rich have not simply accumulated wealth; they have led their times, shaped institutions, and often possessed more resources than nations.

In Roman times, six rich men are said to have owned about half of Africa, and Marcus Antonius Pallas had more wealth than the then emperor Nero.

In the 11th century, the lands of Alan the Red, an English nobleman considered one of the richest men of his time, accounted for approximately 7.3% of England's total net income at the time.

Jay Gould, in the 19th century, controlled 15% of the U.S. railroads, and Jeff Bezos, the richest man of the 21st century, has amassed enough wealth from March to August 2020 alone to pay each of Amazon's 876,000 employees a $100,000 bonus.

While wealth has always been concentrated, the degree of that concentration has grown exponentially since the Industrial Revolution, and has reached its peak once again in the 21st century.

According to "Where Does the Greatest Wealth Come From?", until the mid-19th century, many of Europe's super-rich were of noble birth, and in the 20th century, self-made millionaires who made their fortunes through commerce and finance emerged.

But in recent decades, the share of wealthy people passing down their wealth through inheritance has been rising again, and the concentration of wealth in the top 0.1% has surpassed levels seen just before the Great Depression in 1929.

Inequality that doesn't disappear: "What do we expect from the rich, and what are we disappointed about?"

With the exception of the Black Death and the World Wars, wealth inequality has steadily increased over the centuries.

Europe temporarily became more equal after the Black Death in the 14th century, but inequality began to increase again from the 15th century.

Especially with the rise of finance during the Industrial Revolution, entrepreneurs and financiers replaced the aristocrats of the past as the new super-rich.

They have grown beyond being simply 'rich' to become entities that move institutions and power.

The United States, on the other hand, started somewhat differently.

In the absence of aristocracy and hereditary privilege, America in its early years was a relatively egalitarian society.

However, industrialization, the development of railroads, and the rapid development of the financial system since the mid-19th century accelerated wealth inequality.

Today, the United States produces more than half of the world's super-rich and is considered one of the most unequal countries.

Concentration of wealth is no longer just a story of the aristocracy of the past.

This is the reality that is happening right before our eyes.

"Where Does the Greatest Wealth Come From?" traces the historical flow and concentration of wealth, and analyzes in detail the birth and changes of the wealthy in each era, as well as the complex positions they have held in society, from the traditional super-rich who formed "families" like the Rothschilds, Fuggers, and Medicis, to modern-day tech billionaires like Bill Gates, Mark Zuckerberg, and Jeff Bezos.

Alfani systematically tells this story, crossing data and statistics, philosophy and politics, individuals and institutions, illuminating not simply the actions of wealthy individuals but the origins of the social structure of "wealth."

Consumption is luxury, saving is accumulation?! The dilemma of the super-rich.

In the past, the rich were always the objects of suspicion and criticism in Western society.

Medieval monks considered the rich to be sinners, and those who pursued private gain over the public good were subject to banishment.

But when social crises such as epidemics, wars, and crop failures struck, the rich took on the role of 'saviors.'

By donating, paying taxes, building infrastructure, and providing loans, they contributed to the community, thereby gaining legitimacy and social trust.

But what about today? They've managed to preserve their wealth through pandemics and global financial crises, but they're shirking their responsibility to the community.

Alfani says:

“Historically, when the rich fail to contribute to society, and when they are seen or suspected of being insensitive to the suffering of the masses and exploiting that suffering for profit, society becomes unstable, leading to riots and uprisings.” Even temporary tax increases are seen as a “war on the rich,” and they have reached the point where they are instead using public taxes to cover their own losses.

Asking the rich why they exist

If in the past the wealthy secured legitimacy by functioning as a "responsible class," today we may be witnessing the collapse of that legitimacy.

Saying, “I would rather donate than pay taxes” is not just an empty declaration.

As in the past, the rich still seek to gain the moral high ground by donating and avoiding taxes.

The author sharply examines the historical debate between "good faith" and "duty," revealing the underlying logic of power and the shifting social contract.

This book is not just a history book that illuminates the past, but also a warning for the future.

"Where Does the Greatest Wealth Come From?" explores the history of power, legitimacy, and responsibility of the super-rich, spanning past and present.

And he asks us:

Do today's wealthy truly deserve to exist? What should we do when the world is ruled by wealthy people who no longer contribute to society?

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 25, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 528 pages | 772g | 154*225*27mm

- ISBN13: 9791193638880

- ISBN10: 1193638887

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)