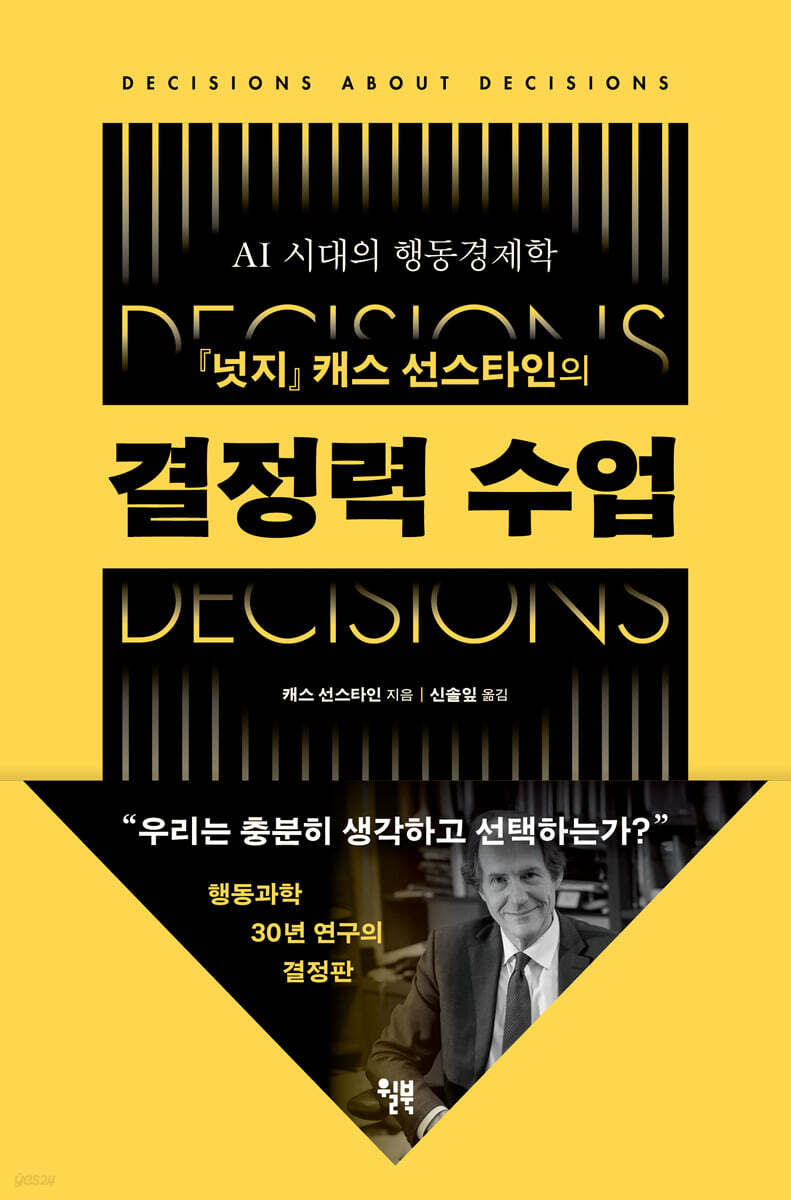

Decision-making class

|

Description

Book Introduction

★ The essence of behavioral economics and decision-making theory, researched for nearly 30 years by Cass Sunstein, co-author of Nudge and Noise.

★ “An adventurous voyage exploring the burden of decision-making, environmental protection, and freedom of the press!”

★ Selection and decision strategies for prudent leaders in an era of advanced artificial intelligence, political polarization, and information overload.

Harvard Law School professor Cass Sunstein answers today's crucial question: "Are (artificial intelligence) algorithms fairer and wiser than human judges?"

“Yes.

“We want to break free, but the harmful effects of cognitive biases that dominate us can be overcome with algorithms.”

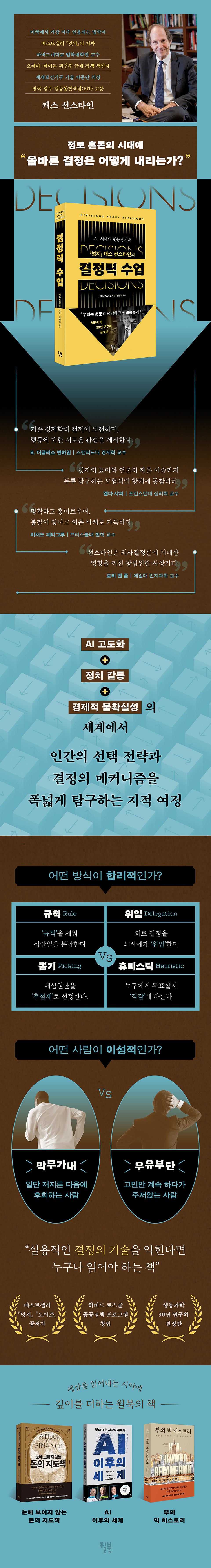

From deciding what to have for lunch to making political decisions, "Decision Making" examines the big and small decisions we make in our daily lives, what decision-making methods are rational, and the pitfalls and contradictions people fall into.

When faced with a critical juncture that could change our lives 180 degrees, what questions should we ask ourselves to navigate in the right direction? Is knowledge power, or is ignorance bliss? Why do political beliefs tend to be so extreme? And, most urgently, "Should humans follow algorithms?" This book delves deeply and broadly into a variety of questions.

A prudent person does not make rash decisions.

A leader is someone who 'decides how to decide'.

This book introduces a secondary decision-making strategy (decision-about-decision) that approaches decisions in two steps rather than making hasty judgments on the spot.

Companies manage their employees by establishing 'rules'.

If information is lacking, the decision is 'delegated' to an expert, such as a doctor or lawyer.

Sometimes we rely on 'intuition (heuristics)'.

When exactly is the most appropriate strategy? This book explores a variety of key dimensions, including the burden of decision-making, responsibility, equality, and fairness, and allows us to discover answers tailored to our individual circumstances.

The book presents some interesting behavioral science research.

One study found that human judges were more likely to release defendants when their mugshots were neat rather than messy.

This 'mugshot bias' is one reason why algorithms are better than humans.

Studies that surveyed people's beliefs about climate change have shown that people are more likely to believe information that aligns with their existing beliefs, a phenomenon known as "biased assimilation," which provides further insight into the polarization of political beliefs.

“We live in an age when liberalism is under great pressure,” the author concludes, praising the diversity of choice and the autonomy of decision-making.

We live in an age where high-performance artificial intelligence churns out creations indistinguishable from reality, where ideological conflicts intensify, and where fake news and malicious propaganda and marketing attempt to distort our judgment and manipulate our decisions.

Let's cultivate unwavering decision-making power with this book, which offers insight into everything from economics to psychology, law, public policy, and philosophy.

★ “An adventurous voyage exploring the burden of decision-making, environmental protection, and freedom of the press!”

★ Selection and decision strategies for prudent leaders in an era of advanced artificial intelligence, political polarization, and information overload.

Harvard Law School professor Cass Sunstein answers today's crucial question: "Are (artificial intelligence) algorithms fairer and wiser than human judges?"

“Yes.

“We want to break free, but the harmful effects of cognitive biases that dominate us can be overcome with algorithms.”

From deciding what to have for lunch to making political decisions, "Decision Making" examines the big and small decisions we make in our daily lives, what decision-making methods are rational, and the pitfalls and contradictions people fall into.

When faced with a critical juncture that could change our lives 180 degrees, what questions should we ask ourselves to navigate in the right direction? Is knowledge power, or is ignorance bliss? Why do political beliefs tend to be so extreme? And, most urgently, "Should humans follow algorithms?" This book delves deeply and broadly into a variety of questions.

A prudent person does not make rash decisions.

A leader is someone who 'decides how to decide'.

This book introduces a secondary decision-making strategy (decision-about-decision) that approaches decisions in two steps rather than making hasty judgments on the spot.

Companies manage their employees by establishing 'rules'.

If information is lacking, the decision is 'delegated' to an expert, such as a doctor or lawyer.

Sometimes we rely on 'intuition (heuristics)'.

When exactly is the most appropriate strategy? This book explores a variety of key dimensions, including the burden of decision-making, responsibility, equality, and fairness, and allows us to discover answers tailored to our individual circumstances.

The book presents some interesting behavioral science research.

One study found that human judges were more likely to release defendants when their mugshots were neat rather than messy.

This 'mugshot bias' is one reason why algorithms are better than humans.

Studies that surveyed people's beliefs about climate change have shown that people are more likely to believe information that aligns with their existing beliefs, a phenomenon known as "biased assimilation," which provides further insight into the polarization of political beliefs.

“We live in an age when liberalism is under great pressure,” the author concludes, praising the diversity of choice and the autonomy of decision-making.

We live in an age where high-performance artificial intelligence churns out creations indistinguishable from reality, where ideological conflicts intensify, and where fake news and malicious propaganda and marketing attempt to distort our judgment and manipulate our decisions.

Let's cultivate unwavering decision-making power with this book, which offers insight into everything from economics to psychology, law, public policy, and philosophy.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

preface

Chapter 1: Prudent Strategy: Deciding How to Make Decisions

Chapter 2: Questions to Ask at Crossroads in Life

Chapter 3: Is knowledge power or ignorance bliss?

Chapter 4: Polarization of Political Beliefs: Belief in Climate Change

Chapter 5: Keep Your Faith or Change It

Chapter 6: When and How Consistency Breaks Down

Chapter 7: Economics for Rational and Valuable Consumption

Chapter 8: Why I Can't Quit Social Media Even When I Know It's Making Me Unhappy

Chapter 9: Are Algorithms Fairer and Smarter?

Chapter 10: Take control of your life

Conclusion “Take it!”

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1: Prudent Strategy: Deciding How to Make Decisions

Chapter 2: Questions to Ask at Crossroads in Life

Chapter 3: Is knowledge power or ignorance bliss?

Chapter 4: Polarization of Political Beliefs: Belief in Climate Change

Chapter 5: Keep Your Faith or Change It

Chapter 6: When and How Consistency Breaks Down

Chapter 7: Economics for Rational and Valuable Consumption

Chapter 8: Why I Can't Quit Social Media Even When I Know It's Making Me Unhappy

Chapter 9: Are Algorithms Fairer and Smarter?

Chapter 10: Take control of your life

Conclusion “Take it!”

Acknowledgements

Detailed image

Into the book

When we make decisions, material outcomes are important.

Money is important, health is important, and stability is important.

But people's emotional experiences are also important, and we should focus on this when making decisions.

Actual and anticipated emotions lead us in the right or wrong direction.

The reason you believe something may be partly because you want to believe it.

--- p.10, from the “Preface”

Second-order decisions are a strategy used by people who don't want to get into ordinary decision-making situations in the first place.

There are important issues here: cognitive load, responsibility, equality, and fairness.

Setting 'rules' is also an example of a secondary decision.

In our daily lives, we often follow strict rules.

For example, you should never lie or do anything dishonest, or you should never drink alcohol before a meal.

--- p.20, from “Chapter 1: Prudent Strategy: Deciding How to Decide”

To understand these issues, securing data is paramount.

Data that determines whether people who made or did not make a choice are generally satisfied with or regret their decision.

The existing evidence points to one simple and shocking conclusion.

People benefit from making major changes in their lives, and sticking to the status quo is far more likely to lead to regret and unhappiness.

For example, in situations like ending a relationship or quitting a job, it is clear that people are more likely to make mistakes when they decide to be cautious rather than bold.

--- p.74, from “Chapter 2: Questions to Ask at the Crossroads of Life”

People will naturally assume that they need to know 'something' and therefore that acquiring information is always beneficial.

However, this conclusion is too definitive.

Sometimes we don't want to know.

When exactly is information a good thing? How good is it, exactly? How do we decide whether to seek information or avoid it? Information avoidance is a core characteristic of human life.

Sometimes we take active steps to avoid information.

--- p.83, from “Chapter 3: Is knowledge power or is ignorance weakness?”

When predicting an individual's likelihood, good news is usually more influential than bad news, regardless of prior beliefs.

This is the good news-bad news effect.

Let's say you've been told that you're smarter than you think.

Would you believe this? Or if you were told you were more handsome than you thought? People generally trust good news more than bad news.

--- pp.121-122, from “Chapter 4 Polarization of Political Beliefs: Belief in Climate Change”

The same method can effectively counter misinformation and ‘fake news’.

In some cases, correcting incorrect information doesn't work because people don't want to believe it, regardless of whether it's accurate.

In extreme cases, corrections can backfire, giving greater support to the beliefs they are supposed to refute.

One reason this phenomenon occurs is because people believe that changing their beliefs will in some way cause them to experience suffering.

--- p.153, from “Chapter 5: Keep the Faith or Change It”

For example, when choosing a slice of chocolate cake, if I were to compare only two pieces, small piece A and medium piece B, I would prefer A.

But if I were given three choices here, including a large slice, my choice would be a medium-sized piece of cake.

And you end up choosing B over A.

This can be understood as a heuristic for choosing the middle option.

In trying to avoid extremes, people are easily deceived.

The seller deliberately adds the less attractive option C to options A and B to encourage people to choose B instead of A.

Politicians also use the same tactic, exploiting the compromise effect to get people to choose the more expensive option.

--- p.170, from “Chapter 6: When and How Does Consistency Break Down”

Many critics have pointed out the atomistic and isolated nature of relationships in a market economy and the antisocial and highly individualistic mindset that the market seems to express and promote.

While there is certainly some truth to this point, there are other aspects as well.

Consumption patterns in everyday life reflect various social impulses, even the drive to form communities.

When choosing what to buy, consumers connect not only with products but also with other customers.

--- p.201, from “Chapter 7 Economics for Rational and Valuable Consumption”

When people stopped using Facebook, they became less interested in politics.

Members of the church group were less likely to give correct answers to questions about recent news.

Fewer people said they checked political news.

Perhaps for this reason, deactivating Facebook significantly reduced the degree of political polarization.

On political questions, Democrats and Republicans in the church group disagreed less than those in the control group.

It's reasonable to assume that as people learn about politics on Facebook pages, they are exposed to stories that are biased towards their personal preferences, which in turn exacerbates polarization.

--- p.248, from “Chapter 8: Why I Can’t Quit Social Media Even Though I Know It Will Make Me Unhappy”

An interesting study by economists Jens Ludwig and Sendhil Mullanassen shows another reason why algorithms are better than judges.

Even after controlling for race, skin color, and demographic factors, judges placed greater weight on mugshots (photos taken of suspects after their arrest) than the algorithms! Perhaps unsurprisingly, judges react to the "well-groomed" appearance of defendants in mugshots.

Judges were more likely to release clean, neat defendants than disheveled, unkempt, and messy defendants.

--- p.263, from “Chapter 9: Are Algorithms Fairer and Wiser?”

In law and in everyday language, fraud usually means lying and misrepresenting facts for some gain.

“If you buy this product, you will never get cancer!” Deception is generally any word or action intended to make people believe something that is not true.

“The COVID vaccine is ineffective!” In everyday language, manipulation is a broader concept, different from the two above, and encompasses several important aspects.

If the checkbox that says "Your subscription will automatically renew annually at the tripled price" is pre-checked, it may not be a scam and no one will be deceived, but it is manipulation.

--- pp.289-290, from “Chapter 10: Take control of your life’s decisions”

One of my close friends, whom I'll call David, has a mild heart condition that puts him at high risk for stroke.

To lower this risk, his doctor told him to take medication every day.

It was not a drug without side effects, and it could increase the risk of bleeding.

Nevertheless, the doctor thought it would be wise for David to take this medication.

David decided not to take the medication.

He decided that if you look at the odds alone, either way there was a risk, and he didn't like the idea of taking medication every day or having to take medication every day.

The doctor said he didn't agree with the idea, but the decision itself wasn't unreasonable.

The doctor added that he was taught in the medical field that "patient autonomy" must be respected.

Why should you respect it? "After all, it's your life."

Money is important, health is important, and stability is important.

But people's emotional experiences are also important, and we should focus on this when making decisions.

Actual and anticipated emotions lead us in the right or wrong direction.

The reason you believe something may be partly because you want to believe it.

--- p.10, from the “Preface”

Second-order decisions are a strategy used by people who don't want to get into ordinary decision-making situations in the first place.

There are important issues here: cognitive load, responsibility, equality, and fairness.

Setting 'rules' is also an example of a secondary decision.

In our daily lives, we often follow strict rules.

For example, you should never lie or do anything dishonest, or you should never drink alcohol before a meal.

--- p.20, from “Chapter 1: Prudent Strategy: Deciding How to Decide”

To understand these issues, securing data is paramount.

Data that determines whether people who made or did not make a choice are generally satisfied with or regret their decision.

The existing evidence points to one simple and shocking conclusion.

People benefit from making major changes in their lives, and sticking to the status quo is far more likely to lead to regret and unhappiness.

For example, in situations like ending a relationship or quitting a job, it is clear that people are more likely to make mistakes when they decide to be cautious rather than bold.

--- p.74, from “Chapter 2: Questions to Ask at the Crossroads of Life”

People will naturally assume that they need to know 'something' and therefore that acquiring information is always beneficial.

However, this conclusion is too definitive.

Sometimes we don't want to know.

When exactly is information a good thing? How good is it, exactly? How do we decide whether to seek information or avoid it? Information avoidance is a core characteristic of human life.

Sometimes we take active steps to avoid information.

--- p.83, from “Chapter 3: Is knowledge power or is ignorance weakness?”

When predicting an individual's likelihood, good news is usually more influential than bad news, regardless of prior beliefs.

This is the good news-bad news effect.

Let's say you've been told that you're smarter than you think.

Would you believe this? Or if you were told you were more handsome than you thought? People generally trust good news more than bad news.

--- pp.121-122, from “Chapter 4 Polarization of Political Beliefs: Belief in Climate Change”

The same method can effectively counter misinformation and ‘fake news’.

In some cases, correcting incorrect information doesn't work because people don't want to believe it, regardless of whether it's accurate.

In extreme cases, corrections can backfire, giving greater support to the beliefs they are supposed to refute.

One reason this phenomenon occurs is because people believe that changing their beliefs will in some way cause them to experience suffering.

--- p.153, from “Chapter 5: Keep the Faith or Change It”

For example, when choosing a slice of chocolate cake, if I were to compare only two pieces, small piece A and medium piece B, I would prefer A.

But if I were given three choices here, including a large slice, my choice would be a medium-sized piece of cake.

And you end up choosing B over A.

This can be understood as a heuristic for choosing the middle option.

In trying to avoid extremes, people are easily deceived.

The seller deliberately adds the less attractive option C to options A and B to encourage people to choose B instead of A.

Politicians also use the same tactic, exploiting the compromise effect to get people to choose the more expensive option.

--- p.170, from “Chapter 6: When and How Does Consistency Break Down”

Many critics have pointed out the atomistic and isolated nature of relationships in a market economy and the antisocial and highly individualistic mindset that the market seems to express and promote.

While there is certainly some truth to this point, there are other aspects as well.

Consumption patterns in everyday life reflect various social impulses, even the drive to form communities.

When choosing what to buy, consumers connect not only with products but also with other customers.

--- p.201, from “Chapter 7 Economics for Rational and Valuable Consumption”

When people stopped using Facebook, they became less interested in politics.

Members of the church group were less likely to give correct answers to questions about recent news.

Fewer people said they checked political news.

Perhaps for this reason, deactivating Facebook significantly reduced the degree of political polarization.

On political questions, Democrats and Republicans in the church group disagreed less than those in the control group.

It's reasonable to assume that as people learn about politics on Facebook pages, they are exposed to stories that are biased towards their personal preferences, which in turn exacerbates polarization.

--- p.248, from “Chapter 8: Why I Can’t Quit Social Media Even Though I Know It Will Make Me Unhappy”

An interesting study by economists Jens Ludwig and Sendhil Mullanassen shows another reason why algorithms are better than judges.

Even after controlling for race, skin color, and demographic factors, judges placed greater weight on mugshots (photos taken of suspects after their arrest) than the algorithms! Perhaps unsurprisingly, judges react to the "well-groomed" appearance of defendants in mugshots.

Judges were more likely to release clean, neat defendants than disheveled, unkempt, and messy defendants.

--- p.263, from “Chapter 9: Are Algorithms Fairer and Wiser?”

In law and in everyday language, fraud usually means lying and misrepresenting facts for some gain.

“If you buy this product, you will never get cancer!” Deception is generally any word or action intended to make people believe something that is not true.

“The COVID vaccine is ineffective!” In everyday language, manipulation is a broader concept, different from the two above, and encompasses several important aspects.

If the checkbox that says "Your subscription will automatically renew annually at the tripled price" is pre-checked, it may not be a scam and no one will be deceived, but it is manipulation.

--- pp.289-290, from “Chapter 10: Take control of your life’s decisions”

One of my close friends, whom I'll call David, has a mild heart condition that puts him at high risk for stroke.

To lower this risk, his doctor told him to take medication every day.

It was not a drug without side effects, and it could increase the risk of bleeding.

Nevertheless, the doctor thought it would be wise for David to take this medication.

David decided not to take the medication.

He decided that if you look at the odds alone, either way there was a risk, and he didn't like the idea of taking medication every day or having to take medication every day.

The doctor said he didn't agree with the idea, but the decision itself wasn't unreasonable.

The doctor added that he was taught in the medical field that "patient autonomy" must be respected.

Why should you respect it? "After all, it's your life."

--- p.307, from “Conclusion: Take it!”

Publisher's Review

When information overload clouds our vision and evil marketing attempts to manipulate our thoughts,

A behavioral economics class that cultivates the inner strength to make rational decisions.

What was Donald Trump's "money bomb" strategy, which siphoned off $60 billion in campaign contributions from ordinary people? In March 2020, donors to the Trump campaign received a form online, filled with tiny print.

The box labeled 'Monthly Regular Donation' was already checked.

Furthermore, in September, the pre-checked "Monthly Regular Donation" text was changed to "Weekly Regular Donation" and moved below the other text to make it less noticeable.

Researchers at Columbia Business School found that this strategy, called "dark defaults," increased Trump's income by $42 million.

We live in a post-truth era, where fake news that distorts the truth is rampant, and conspiracy theories spread that claim elections were rigged or spies started forest fires.

Meanwhile, the clever propaganda and agitation that takes place easily extorts money, time, and effort.

Moreover, advanced artificial intelligence is churning out blatant false information, shaking the very foundations of knowledge, consumption, and belief, shaping our choices about what we know, what we buy, and what we believe.

In this situation, a book has been published for those who cannot make a clear decision and only worry, or who make a hasty decision and then regret it.

This is 『Decision Making Lessons』 by Cass Sunstein, a Harvard law professor and behavioral economist famous for 'nudge'.

This book teaches "second-order decisions" strategies for people who don't want to engage in ordinary decision-making situations, either because they lack accurate information or because the burden is too great.

In what situations is the most rational approach—establishing a few "standards," breaking down major decisions into "small steps" and making them incrementally, or using random "drawing"—a key and distinctive feature of this book is that it doesn't simply approach them through economics' cost-benefit analysis.

Decisions involve more than just me, and we are sometimes subject to cognitive biases and are also emotionally driven beings.

The author takes all of this into consideration in detail and seeks the most desirable decision-making method.

“In every important respect, the algorithm outperforms a real judge.”

Answering the urgent question of how much trust we can have in artificial intelligence algorithms

Cornell University computer scientist John Kleinberg conducted a study comparing the judgment of algorithms and human judges.

How well can algorithms solve the crucial problem of deciding whether to detain or release a defendant in a criminal case? The most desirable approach would be to simultaneously reduce the incarceration rate and the crime rate.

The researchers created an algorithm that fed judges data on the defendant's past criminal records and current misconduct.

Remarkably, the algorithm was able to reduce crime rates by 24.7 percent when keeping incarceration rates the same as human judges.

This means that using algorithms, thousands of crimes could be prevented without a single additional inmate.

Meanwhile, human judges made a major mistake, freeing 48.5 percent of defendants the algorithm judged to be in the top 1 percent of the most dangerous.

The likelihood of their being re-arrested was 62.7 percent.

That is, the judge gave lenient punishment to people who had a high possibility of committing a crime.

This book addresses today's pressing issue of 'algorithmic decision-making.'

Is it better to rely on algorithms for decisions? If so, when should we use them? Are algorithms biased? If so, how? The author boldly argues and strongly supports algorithmic decision-making.

But at the same time, it broadly illuminates the widespread algorithmic aversion among people and what algorithms cannot do (can they predict revolutions?), while not neglecting the most important premise.

Ultimately, the decision is something we make and must make ourselves, a free human being's 'subjectivity'.

“People believe what they want to believe.”

Mechanisms and Solutions for Political Polarization Revealed by a Survey of Beliefs About Climate Change

By 2024, the global average temperature will rise by 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels, marking the first time the climate crisis has been crossed.

Reactions vary, from those experiencing severe anxiety and climate depression to those who deny it as an unfair conspiracy.

To explore this, the authors surveyed 302 Americans online to study how people form beliefs and how they update their beliefs after encountering new information.

First, we surveyed the participants' tendencies to determine whether they had high or low beliefs about climate change (those who thought climate change was serious) or low beliefs (those who thought it was not that serious), and then asked them to estimate how much the average temperature in the United States would rise by 2100.

Next, we gave each participant different pieces of good news—that the average temperature would rise less than previously predicted—and bad news—that the temperature would rise more than previously predicted—and asked them to give their estimates again.

As a result, people with high confidence adjusted their estimates further when they heard bad news, and people with low confidence adjusted their estimates further when they heard good news.

That is, they reacted more strongly to things that reinforced their existing beliefs.

The authors describe this as 'asymmetrical updating'.

For example, for people who are worried about the severity of climate change, the good news that it is better than expected creates dissonance.

It is unpleasant to suggest that the worries so far have been excessive.

People also 'rationally' distrust the news itself.

"Climate change isn't that bad? Could it be that some industry is taking money?" This situation is also evident on the other side, and political beliefs are polarized in the same way not only on climate change but on a variety of other topics.

Is there a solution? The author analyzes the nature of beliefs in more detail and synthesizes various psychological research findings and policy data to propose several approaches.

The author's expertise, having advised the World Bank and various government officials on legal and public policy issues and serving as head of regulatory policy in the Obama and Biden administrations, is fully demonstrated in this book.

Things to Consider Before Making Important Life Choices

When we meet new people, we categorize them into general categories, such as whether they are male or female, young or old, and act accordingly.

Is it irrational to follow such heuristics (mental shortcuts)? Heuristics have attracted significant attention because they are known to lead to irrational behaviors, such as erroneous biases and discrimination.

However, when there is so much to know and decisions are difficult to make, this method can yield quite good results.

If you think about it that way, the author says, heuristics are generally reasonable.

Professor Hunt Alcott of New York University found that when people quit Facebook, they experienced significant reductions in depression and anxiety, significantly higher levels of happiness, and significantly lower political polarization.

However, subsequent studies have found that even when people are aware of this fact, they still want to use Facebook.

Some people even mock social media users by saying, "Escape from SNS is about intelligence."

Are people who can't quit social media even though they know it will make them unhappy really irrational?

『Decision Making Class』 fundamentally gives one great realization.

From choosing today's lunch menu to the presidential election that will be our responsibility for the next five years, the situations in which decisions must be made are extremely diverse, and there are countless people in the world, each with their own rationality.

This book helps each person make the right decision through colorful and comprehensive analysis.

If you are facing an important life choice, read this book and develop the power to think and decide for yourself.

A behavioral economics class that cultivates the inner strength to make rational decisions.

What was Donald Trump's "money bomb" strategy, which siphoned off $60 billion in campaign contributions from ordinary people? In March 2020, donors to the Trump campaign received a form online, filled with tiny print.

The box labeled 'Monthly Regular Donation' was already checked.

Furthermore, in September, the pre-checked "Monthly Regular Donation" text was changed to "Weekly Regular Donation" and moved below the other text to make it less noticeable.

Researchers at Columbia Business School found that this strategy, called "dark defaults," increased Trump's income by $42 million.

We live in a post-truth era, where fake news that distorts the truth is rampant, and conspiracy theories spread that claim elections were rigged or spies started forest fires.

Meanwhile, the clever propaganda and agitation that takes place easily extorts money, time, and effort.

Moreover, advanced artificial intelligence is churning out blatant false information, shaking the very foundations of knowledge, consumption, and belief, shaping our choices about what we know, what we buy, and what we believe.

In this situation, a book has been published for those who cannot make a clear decision and only worry, or who make a hasty decision and then regret it.

This is 『Decision Making Lessons』 by Cass Sunstein, a Harvard law professor and behavioral economist famous for 'nudge'.

This book teaches "second-order decisions" strategies for people who don't want to engage in ordinary decision-making situations, either because they lack accurate information or because the burden is too great.

In what situations is the most rational approach—establishing a few "standards," breaking down major decisions into "small steps" and making them incrementally, or using random "drawing"—a key and distinctive feature of this book is that it doesn't simply approach them through economics' cost-benefit analysis.

Decisions involve more than just me, and we are sometimes subject to cognitive biases and are also emotionally driven beings.

The author takes all of this into consideration in detail and seeks the most desirable decision-making method.

“In every important respect, the algorithm outperforms a real judge.”

Answering the urgent question of how much trust we can have in artificial intelligence algorithms

Cornell University computer scientist John Kleinberg conducted a study comparing the judgment of algorithms and human judges.

How well can algorithms solve the crucial problem of deciding whether to detain or release a defendant in a criminal case? The most desirable approach would be to simultaneously reduce the incarceration rate and the crime rate.

The researchers created an algorithm that fed judges data on the defendant's past criminal records and current misconduct.

Remarkably, the algorithm was able to reduce crime rates by 24.7 percent when keeping incarceration rates the same as human judges.

This means that using algorithms, thousands of crimes could be prevented without a single additional inmate.

Meanwhile, human judges made a major mistake, freeing 48.5 percent of defendants the algorithm judged to be in the top 1 percent of the most dangerous.

The likelihood of their being re-arrested was 62.7 percent.

That is, the judge gave lenient punishment to people who had a high possibility of committing a crime.

This book addresses today's pressing issue of 'algorithmic decision-making.'

Is it better to rely on algorithms for decisions? If so, when should we use them? Are algorithms biased? If so, how? The author boldly argues and strongly supports algorithmic decision-making.

But at the same time, it broadly illuminates the widespread algorithmic aversion among people and what algorithms cannot do (can they predict revolutions?), while not neglecting the most important premise.

Ultimately, the decision is something we make and must make ourselves, a free human being's 'subjectivity'.

“People believe what they want to believe.”

Mechanisms and Solutions for Political Polarization Revealed by a Survey of Beliefs About Climate Change

By 2024, the global average temperature will rise by 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels, marking the first time the climate crisis has been crossed.

Reactions vary, from those experiencing severe anxiety and climate depression to those who deny it as an unfair conspiracy.

To explore this, the authors surveyed 302 Americans online to study how people form beliefs and how they update their beliefs after encountering new information.

First, we surveyed the participants' tendencies to determine whether they had high or low beliefs about climate change (those who thought climate change was serious) or low beliefs (those who thought it was not that serious), and then asked them to estimate how much the average temperature in the United States would rise by 2100.

Next, we gave each participant different pieces of good news—that the average temperature would rise less than previously predicted—and bad news—that the temperature would rise more than previously predicted—and asked them to give their estimates again.

As a result, people with high confidence adjusted their estimates further when they heard bad news, and people with low confidence adjusted their estimates further when they heard good news.

That is, they reacted more strongly to things that reinforced their existing beliefs.

The authors describe this as 'asymmetrical updating'.

For example, for people who are worried about the severity of climate change, the good news that it is better than expected creates dissonance.

It is unpleasant to suggest that the worries so far have been excessive.

People also 'rationally' distrust the news itself.

"Climate change isn't that bad? Could it be that some industry is taking money?" This situation is also evident on the other side, and political beliefs are polarized in the same way not only on climate change but on a variety of other topics.

Is there a solution? The author analyzes the nature of beliefs in more detail and synthesizes various psychological research findings and policy data to propose several approaches.

The author's expertise, having advised the World Bank and various government officials on legal and public policy issues and serving as head of regulatory policy in the Obama and Biden administrations, is fully demonstrated in this book.

Things to Consider Before Making Important Life Choices

When we meet new people, we categorize them into general categories, such as whether they are male or female, young or old, and act accordingly.

Is it irrational to follow such heuristics (mental shortcuts)? Heuristics have attracted significant attention because they are known to lead to irrational behaviors, such as erroneous biases and discrimination.

However, when there is so much to know and decisions are difficult to make, this method can yield quite good results.

If you think about it that way, the author says, heuristics are generally reasonable.

Professor Hunt Alcott of New York University found that when people quit Facebook, they experienced significant reductions in depression and anxiety, significantly higher levels of happiness, and significantly lower political polarization.

However, subsequent studies have found that even when people are aware of this fact, they still want to use Facebook.

Some people even mock social media users by saying, "Escape from SNS is about intelligence."

Are people who can't quit social media even though they know it will make them unhappy really irrational?

『Decision Making Class』 fundamentally gives one great realization.

From choosing today's lunch menu to the presidential election that will be our responsibility for the next five years, the situations in which decisions must be made are extremely diverse, and there are countless people in the world, each with their own rationality.

This book helps each person make the right decision through colorful and comprehensive analysis.

If you are facing an important life choice, read this book and develop the power to think and decide for yourself.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: April 30, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 320 pages | 456g | 145*220*21mm

- ISBN13: 9791155818152

- ISBN10: 1155818156

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)