100 Famous Mountains of Japan

|

Description

Book Introduction

The legendary masterpiece "Japan's 100 Famous Mountains"

Meet the 'Best Translation'

The Korean version of 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』 will become an example of the work of reviving a famous work into a famous translation.

be worth.

A translation that carefully considers the uniqueness, usage, and resonance of the words, and extensive annotations.

From maps and photos, to glossaries, a thorough index, and even a comparison of Korean and Japanese fonts, it goes all the way to the end.

We extracted the essence of the original work while pursuing perfection in translation.

“I have stood on the summit of all the hundred famous mountains listed in this book.

Since I had to choose a hundred, I had to climb several mountains.

Regarding selection, I first set three criteria.

The first is the dignity of the mountain.

It should be a mountain that anyone who sees it would admire as a great mountain.

Second, I respect the history of the mountain.

We cannot exclude mountains that have had a deep connection with humans since ancient times.

The third is a mountain with personality.

Just like works of art, something with a distinct personality attracts attention.

“I respect the uniqueness that only a mountain possesses, whether it be its form, its phenomenon, or its tradition, that cannot be found anywhere else.” _ Author’s Note

“This book is composed of 222 pages, each 26 centimeters long, based on the first edition, and each chapter includes a small map and a photograph.

As a translator who agrees with Callimachus's saying, “Mega biblion, mega kakon,” because the absolute amount physically increased during the translation process, I could not shake the thought that excessive notes and annotations could damage the aesthetics of the page and hinder immersion, and that even the well-intentioned notes could contain errors. However, in the end, since this book is not a product of imagination but deals with facts and historical facts, I decided to carefully examine and explain the unfamiliar points that appear in the book.” _Translator’s Preface

Meet the 'Best Translation'

The Korean version of 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』 will become an example of the work of reviving a famous work into a famous translation.

be worth.

A translation that carefully considers the uniqueness, usage, and resonance of the words, and extensive annotations.

From maps and photos, to glossaries, a thorough index, and even a comparison of Korean and Japanese fonts, it goes all the way to the end.

We extracted the essence of the original work while pursuing perfection in translation.

“I have stood on the summit of all the hundred famous mountains listed in this book.

Since I had to choose a hundred, I had to climb several mountains.

Regarding selection, I first set three criteria.

The first is the dignity of the mountain.

It should be a mountain that anyone who sees it would admire as a great mountain.

Second, I respect the history of the mountain.

We cannot exclude mountains that have had a deep connection with humans since ancient times.

The third is a mountain with personality.

Just like works of art, something with a distinct personality attracts attention.

“I respect the uniqueness that only a mountain possesses, whether it be its form, its phenomenon, or its tradition, that cannot be found anywhere else.” _ Author’s Note

“This book is composed of 222 pages, each 26 centimeters long, based on the first edition, and each chapter includes a small map and a photograph.

As a translator who agrees with Callimachus's saying, “Mega biblion, mega kakon,” because the absolute amount physically increased during the translation process, I could not shake the thought that excessive notes and annotations could damage the aesthetics of the page and hinder immersion, and that even the well-intentioned notes could contain errors. However, in the end, since this book is not a product of imagination but deals with facts and historical facts, I decided to carefully examine and explain the unfamiliar points that appear in the book.” _Translator’s Preface

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Translator's Preface | Five Eight Provinces | Prefectures | Baekmyeongsan Mountain Location Map | Title

Part 1 Hokkaido

001 Mount Rishiri

002 Rausudake

003 Sharidake

004 Mount Akandake

005 Daisetsuzan

006 Tomuraushi

007 Tokachidake

008 Mount Porosiri

009 Shiribeshiyama

Part 2 Tohoku

010 Mt. Iwaki

011 Mt. Hakkoda

012 Hachimantai 八幡平

013 Mt. Iwate

014 Hayachine

015 Jokaisan Mountain

016 Gassan Moon Mountain

017 Mount Asahi

018 Zaosan Mountain

019 Mt. Iide

020 Azumayama

021 Adatarayan Mountain

022 Mt. Bandai Mt. Mt.

023 Aizu-Komagatake會津駒ヶ岳

Part 3: Joshinetsu, Oze, Nikko, and Kitakantō

024 Mt. Nasudake

025 Uonuma Komagatake 魚沼駒ヶ岳

026 Hiragatake

027 Makihatayama

028 Hiuchidake

029 Shibutsu Mountain

030 Tanigawadake

031 Amakajariyama

032 Mt. Naeba

033 Mt. Myoko

034 Mt. Hiuchi

035 Takazumayama

036 Nantai Mountain

037 Mount Okushirane

038 Sky Mountain

039 Hotakayama Mt.

040 Mount Akagi

041 Kusatsu Shirane Mountain

042 Azumaya Mountain

043 Asamayama

044 Tsukuba Mountain

Part 4 Northern Alps

045 Shirou-Madake

046 Goryu-dake

047 Mount Kashima Yari

048 Tsurugidake

049 Tateyama

050 Yakushidake

051 Kurobe Gorodake

052 Kurodake

053 Washiba-dake

054 Yarigatake Mt.

055 Hotakadake

056 Mount Jonendake

057 Kasagatake

058 Yakedake

059 Mount Norikura

060 Ontake

Part 5: Utsukushigahara, Yatsugatake, Chichibu, Tama, and Minamikanto

061 Utsukushigahara

062 Kirigamine Mt.

063 Tateshinayama

064 Yatsugatake 八ヶ岳

065 Ryogamisan (Two God Mountains)

066 Kumotoriyama

067 Kobushi-dake

068 Mt. Kinpu

069 Mizugakiyama

070 Daibosatsudake

071 Danzawa Mountain

072 Mount Fuji

073 Amagi Mountain

Part 6 Central Alps Central Alps Southern Alps Southern Alps

074 Kisokomagatake 木曾駒ヶ岳

075 Mt. Utsugi

076 Mount Ena

077 Kaikomagatake

078 Senjodake

079 Mt. Hoozan

080 Kitatake North

081 Ainodake

082 Shiomidake

083 Mount Warusawadake

084 Akaishi-dake

085 Hijiri-dake

086 Dekari-dake

Part 7: Hokuriku, Kinki, Chugoku, and Shikoku

087 Hakusan

088 Mount Arashima

089 Ibukiyama

090 Odaigaharayama

091 Mt. Omine

092 Daisen

093 Tsurugi Mountain

094 Mt. Ishizuchi

Part 8 Kyushu

095 Nine heavy mountains

096 Sobosan Mountain

097 Mt. Aso

098 Kirishimayama

099 Kaimondake Mt. Mt.

100 Miyanouradake

Postscript | Commentary | Translator's Note | Chronology of Kyuya Fukada | References | Table of Contents | Comparison of Old and New Scripts | Index | Mountain Names

Part 1 Hokkaido

001 Mount Rishiri

002 Rausudake

003 Sharidake

004 Mount Akandake

005 Daisetsuzan

006 Tomuraushi

007 Tokachidake

008 Mount Porosiri

009 Shiribeshiyama

Part 2 Tohoku

010 Mt. Iwaki

011 Mt. Hakkoda

012 Hachimantai 八幡平

013 Mt. Iwate

014 Hayachine

015 Jokaisan Mountain

016 Gassan Moon Mountain

017 Mount Asahi

018 Zaosan Mountain

019 Mt. Iide

020 Azumayama

021 Adatarayan Mountain

022 Mt. Bandai Mt. Mt.

023 Aizu-Komagatake會津駒ヶ岳

Part 3: Joshinetsu, Oze, Nikko, and Kitakantō

024 Mt. Nasudake

025 Uonuma Komagatake 魚沼駒ヶ岳

026 Hiragatake

027 Makihatayama

028 Hiuchidake

029 Shibutsu Mountain

030 Tanigawadake

031 Amakajariyama

032 Mt. Naeba

033 Mt. Myoko

034 Mt. Hiuchi

035 Takazumayama

036 Nantai Mountain

037 Mount Okushirane

038 Sky Mountain

039 Hotakayama Mt.

040 Mount Akagi

041 Kusatsu Shirane Mountain

042 Azumaya Mountain

043 Asamayama

044 Tsukuba Mountain

Part 4 Northern Alps

045 Shirou-Madake

046 Goryu-dake

047 Mount Kashima Yari

048 Tsurugidake

049 Tateyama

050 Yakushidake

051 Kurobe Gorodake

052 Kurodake

053 Washiba-dake

054 Yarigatake Mt.

055 Hotakadake

056 Mount Jonendake

057 Kasagatake

058 Yakedake

059 Mount Norikura

060 Ontake

Part 5: Utsukushigahara, Yatsugatake, Chichibu, Tama, and Minamikanto

061 Utsukushigahara

062 Kirigamine Mt.

063 Tateshinayama

064 Yatsugatake 八ヶ岳

065 Ryogamisan (Two God Mountains)

066 Kumotoriyama

067 Kobushi-dake

068 Mt. Kinpu

069 Mizugakiyama

070 Daibosatsudake

071 Danzawa Mountain

072 Mount Fuji

073 Amagi Mountain

Part 6 Central Alps Central Alps Southern Alps Southern Alps

074 Kisokomagatake 木曾駒ヶ岳

075 Mt. Utsugi

076 Mount Ena

077 Kaikomagatake

078 Senjodake

079 Mt. Hoozan

080 Kitatake North

081 Ainodake

082 Shiomidake

083 Mount Warusawadake

084 Akaishi-dake

085 Hijiri-dake

086 Dekari-dake

Part 7: Hokuriku, Kinki, Chugoku, and Shikoku

087 Hakusan

088 Mount Arashima

089 Ibukiyama

090 Odaigaharayama

091 Mt. Omine

092 Daisen

093 Tsurugi Mountain

094 Mt. Ishizuchi

Part 8 Kyushu

095 Nine heavy mountains

096 Sobosan Mountain

097 Mt. Aso

098 Kirishimayama

099 Kaimondake Mt. Mt.

100 Miyanouradake

Postscript | Commentary | Translator's Note | Chronology of Kyuya Fukada | References | Table of Contents | Comparison of Old and New Scripts | Index | Mountain Names

Publisher's Review

The Beginning of All Hundred Famous Mountains: Kyuya Fukada's "One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan"

The Korean edition of 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』, a legendary masterpiece among mountaineers, has been translated for the first time in half a century.

If you search for "Japan's 100 Famous Mountains" in the National Diet Library of Japan, 731 search results appear.

It is so famous that it is the origin of the trend of naming it 'What What Baekmyeongsan'.

This book was published in July 1964, and now even the author's identity has faded, so most people only get a rough idea of it from the materials distributed in advance by travel agencies planning Baekmyeongsan tours.

But now it should be called Fukada Kyuya's "One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan."

On the other hand, among professional mountaineers and mountaineering enthusiasts, 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』 is a standard of authority to support their experiences and claims.

In other words, it is no exaggeration to say that the term Baekmyeongsan has become a hashtag for almost all mountaineering-related content in Japan.

Today, mountaineers in Japan rarely fail to quote a few lines from "One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan" in their communities or blogs.

Additionally, Baekmyeongsan is mentioned without fail in promotional materials for the region, reports and papers by local researchers, and even in matters related to local community organizations.

The same goes for derivative products such as maps, guidebooks, and tour programs, not to mention the accommodations the author stayed in before and after the hike.

Borrowing from the pens of many critics, this book, "100 Famous Mountains of Japan," commonly referred to as the "Bible of Mountains," is an essay on 100 mountains across Japan selected by the author based on their dignity, history, individuality, and heights of over 1,500 meters.

It includes various Japanese traditions by mentioning Japanese mountaineering history and literature in the form of Sanmyeonggo.

However, the mountains described in this book are 60 years old since its publication and 100 years old since the author's mountaineering activities. Nowadays, most mountains have ropeways and automobile roads that reach the top of the mountain, so it seems as if the spirit of the mountain has lost its place to reside.

Many of the facilities that were built on the mountainside during the boom times have now turned into ruins.

In other words, it is difficult to expect the scenery that the mountain had at that time, so this book is insufficient as a guidebook to the 100 famous mountains of Japan that were once leisurely.

Still, it will still be a useful reference for those who actually plan to travel or hike here, and anyone curious about Japanese culture will find plenty of stories to enjoy as a bonus.

Hear directly from the author about the background behind the selection of Baekmyeongsan Mountain.

Japan is a country of mountains.

No matter where you go, there is no place where you cannot see mountains.

There is a handsome mountain overlooking the city, town, and village, and it has an atmosphere that is always included in the school song there.

Most Japanese people grew up seeing mountains.

Although Tokyo is far from mountains, in the past when there was less pollution, Mount Fuji and Mount Tsukuba were important backdrops to the city.

All of the hundred famous mountains listed in this book are mountains the author has stood on top of.

Since I had to choose a hundred, I had to climb several mountains.

In selecting the 100 mountains, the author first set three criteria.

The first is the dignity of the mountain.

It should be a mountain that anyone who sees it would admire as a great mountain.

Even if you pass the exam in terms of height, you won't choose an ordinary mountain.

A mountain that does not have something that touches the human heart, whether it be ruggedness, strength, or beauty, is not smooth.

Just as people have different levels of character, mountains also have different levels of character.

It must be a mountain with a mountain range, not a personality.

Second, the author says he respects the history of the mountain.

We cannot exclude mountains that have had a deep connection with humans since ancient times.

A mountain that people look up to and revere morning and night, and that deserves to have a shrine built on its summit, naturally qualifies as a famous mountain.

The spirit of the mountain resides there.

However, the recent development of the strange tourism industry has commercialized famous mountains with long histories, and the spirit of the mountains has also lost its place to reside.

You can't choose a mountain like that.

The third is a mountain with personality.

Just like works of art, something with a distinct personality attracts attention.

The author respects the uniqueness that only a mountain possesses, whether it be its form, its phenomenon, or its tradition, that cannot be found anywhere else.

The ordinary mountains that are everywhere are not smooth.

Of course, not all mountains are the same shape and each has its own characteristics, but it is the strong individuality among them that draws me in.

As an additional condition, a line of approximately 1500 meters was drawn.

A mountain is not necessarily noble because it is tall, but it must be of a certain height to fall into the category of mountains the author is aiming for.

For example, Mount Yahiko in Echigo, Mount Hiei in Kyoto, and Mount Hiko in Bungo are undoubtedly famous mountains that have been famous since ancient times, but they are very short.

There are exceptions.

Mount Tsukuba and Mount Kaimondake.

The author wrote in the text why he chose it.

Specifically, nine peaks were mentioned in Hokkaido, but other strong candidates include Upepesanke, Nipesosu, Ishikari, Petegari, Ashibetsu, Komagatake, and Tarumaesan.

However, it was excluded for the unfair reason that the author only looked at the mountains and did not actually climb them.

The author says there is no excuse for this.

In the Tohoku region, Akita Komagatake and Kurikomayama should have been included.

Although Mt. Moriyoshi, Mt. Himekami, and Mt. Funagata are good mountains, they are a bit short in height.

The thing the author hesitated about the most was the use of Chosin.

There were plenty of second-class, if not first-class, heights here.

Besides, they are all mountains the author likes.

There are many mountains that would not be out of place among the 100 famous mountains, such as Nyoho-san, Sen-no-kura-san, Kurohime-san, Iizuna-san, Sumon-san, Arasawa-dake, Shirasuna-san, Torikabuto-san, Iwasuge-san, and others.

People often ask Kyuya Fukuda which mountain he likes best.

The author's answer to this question is always set.

This is the most recent mountain I visited.

Because the impression of that mountain is vivid.

Perhaps the mountain I mentioned above as an example would have been included in Baekmyeongsan if I had just returned from there.

It is inevitable that the mountains of the Japanese Alps occupy more than a quarter of the Baekmyeongsan Mountains.

This place, which forms the backbone of Honshu, is quickly over thirty in number just by counting the things that stand out.

The choice among them also puzzled the author.

The mountains that should have been chosen naturally were Yukikura-dake, Okudainichi-dake, Harinoki-dake, Rengedake, Tsubakuro-dake, Otenjo-dake, Kasumizawa-dake, Ariake-yama, Kaki-dake, and Kekachi-dake.

In the south, I also wanted to include Daimugenyama, Jarugatake, and Shichimenzan.

In Hokuriku, I was determined to include Mount Oizurugatake and Mount Ogasayama in the Hakusan Mountain Range.

This is not just because it is the author's hometown mountain, but because he wanted to spread the word to the world that such a wonderful, hidden mountain exists.

However, I regret to say that I have omitted it as I have not yet had the opportunity to climb it.

In addition to Ibukiyama, Odaigaharayama, and Omineyama, which I chose from Kansai, I also wanted to include Suzukayama and Hirayama, which have been famous since ancient times.

I've been to Suzukayama three times.

However, Mount Gozaisho had already become an amusement park, and when he climbed Mount Fujiwaradake and looked out at the mountains of Suzuka, the author hesitated because none of them were high.

Chugoku lacks high mountains.

The day I climbed Hoki Daisen was an exceptionally clear autumn day, and from its summit I gazed upon the spine mountain range that divides Sanyo and Sanin.

My expectation was that there would be a mountain of some kind somewhere.

However, the mountains that were connected in several layers were all flat hills, so there was nothing particularly eye-catching.

I also stopped by Hiruzen, but it was not enough to recommend it as a famous mountain.

I went west again and climbed Mt. Sanbe.

From there, I looked out at the mountains of Nishi-Chugoku.

The result was the same.

The search for famous mountains ended in vain.

In this way, Daisen became one in Chugoku.

If I had to pick one, it would probably be Hyonosen.

The author says that there is no dispute about the two peaks of Shikoku, Mount Ishizuchi and Mount Tsurugi.

Kyushu chose six peaks, and I also had Mount Yufu, Mount Ichifusa, and Mount Sakurajima in mind.

They are all wonderful mountains with their own unique characteristics.

Translation Background and Key Considerations

There were Japanese mountaineers who were often the topic of conversation at after-parties at the group the translator belonged to.

It started with the opening remarks of Professor Kim Young-do (1924-2023).

For example, people like Kogure Ritaro, Tanabe Juji, Oshima Ryokichi, who appear in the main text, and Kushida Magoichi, who wrote the commentary for this book at the end, and Professor Fukada Kyuya were also regulars.

All of them appeared in pairs with their works.

In the sense that everyone has heard of classics, but few have read them, 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』 was no exception, and everyone seemed more curious about the contents than any other book.

Mr. Kim Young-do led the construction of 35 mountain lodges across the country, which began in 1970, and he served as the leader of the 1977 Everest expedition, the first Korean to reach the summit, led by Mr. Ko Sang-don, and the leader of the 1978 Arctic expedition.

Afterwards, he founded the Korea Mountaineering Research Institute, translated several mountaineering books from Gumi, and studied mountaineering history.

One day, the translator asked Mr. Kim Young-do what Japanese mountain book he considered a masterpiece.

After hearing the answer, “『Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains』 is the best,” the translator asked, “Then, would it be okay if you translated it?”

“Because it is such a difficult book to put into words...” was the answer at the time.

As time went by and the translator translated this book, he was able to understand what the words meant.

One day, Kim Jin-deok, a member of the same group as the translator, suggested that we create a small group and read Japanese Shanxi books.

He also said that there is no other book that has had as much influence in Korea and Japan as 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』, and expressed regret that 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』 has not yet been translated.

The translator, who had always been interested in the history of mountaineering in Japan, which is inevitably related to the history of mountaineering in Korea since the modern era, and who knew a little about the mountains of Hokkaido, suggested that we proofread 『One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan』 without much thought, but because he was curious about the content, he ended up taking on the translation himself, which expanded the work.

That doesn't mean the translator had much experience mountaineering in Japan.

If I hadn't received a few responses from friends expressing interest in the rest of the content after translating a few of the Hokkaido mountains that appear in the first part of "One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan," I might have quickly given up on the delusion of wanting to translate the entire work.

As the translation work moved to Honshu, it began to sink into the swamp of Japan's unique diversity.

Sanmyeonggo was beginning to reveal its true colors.

Stories about mountains all over Japan were intertwined, as if they were being spoken in the dialects of each of the eight provinces.

Moreover, because the author himself wrote with the principle of having five 400-character manuscript pages per chapter, the book was surprisingly vast when unzipped.

For example, there is a place name called Nakaguchi that appears in the 'Arashimadake' section.

This can be read in various ways, but finding a local reading was difficult, and not wanting to be vague, the translator personally looked up road signs in the area and found that it is read as 'Nakande'.

This book, based on the first edition, is a 26-centimeter hardcover book with 222 pages, each containing a small map and a photograph.

Since this book is not a product of imagination but deals with facts and historical facts, I decided to carefully examine and explain the unfamiliar points that appear in the book.

The footnotes in the text are intended to reflect a range of perspectives.

Japanese cultural history is difficult to interpret with a single, defined concept because it contains many exceptional elements, and there are many parts where it is difficult to find a logical structure that presupposes regularity.

Therefore, I do not believe that the translation has universality and it is natural that it may convey contradictory or insufficient information.

However, in order to increase objectivity, we tried not to quote anything without a source other than the translator's opinion.

In addition to referencing books and papers, I also accessed digital resources from public libraries in Japan.

In Japanese encyclopedias, I checked and referenced only the articles with authors listed, and in Japanese Wikipedia, which has a vast amount of data but also contains incorrect information, I only checked and referenced the parts with sources.

Each country has developed its own unique language to express nature or natural phenomena from early on.

However, people today who are accustomed to city life have less opportunity to experience and describe in detail the changes in weather and terrain as people in the past did, so expressions related to these may feel unfamiliar.

However, since it is an essential element in articles dealing with mountaineering, I first collected forgotten Korean words related to it and adopted them appropriately based on my experience climbing Korean and Japanese mountains.

I consulted several maps to confirm the parts related to the description of the terrain. I grasped the overall terrain through the detailed map of the Geographical Survey Institute of Japan (Electronic National Land Web), and I used commercially available bird's-eye views and mountaineering maps to determine the approach.

We checked the hiking trail, the actual shape of the mountain, its relationship with the surrounding terrain, and whether facilities or structures were still in existence.

I want to talk about photography.

There were many difficulties in selecting the photos to include in the text.

In order to capture the characteristics of the mountain, I had no choice but to choose a photo that contained the entirety of the mountain.

Also, to explain in captions, you need to know where the photo was taken and from.

In the end, I had no choice but to follow the gaze of other climbers who had chosen that route, and in the process, I passed by so many beautiful places that I wanted to see and that were too precious to just take in with my eyes, that those words struck me anew.

However, it is realistically difficult to reveal all of the mountain's expressions on the page of the text.

Anyway, I tried to select all the photos that were most relevant to the content of the text.

However, there were many regrettable moments when there were not suitable photos in all the necessary places, and when luck did not follow the photographer's will to capture the decisive scene while climbing the rugged mountain.

So, of course, there are some photos that are not well-made or not very good, so I don't think we can judge the beauty of the mountain based on that alone.

Rather, I hesitated, fearing that these few photos, which are nothing more than mere glimpses of the mountain, would not only shatter the illusion of the famous mountain but also plant false preconceptions. However, in the end, the translator, who must know the contents of the book best, chose to include them.

About the life of Kyuya Fukuda

『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』 largely overlaps in subject matter and content with several essays on mountains that the author has previously published.

That is, the author wrote several essays about the same mountain.

In this way, the author spent a long time preparing 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』, refining and polishing the text.

Thanks to this, the texture of this book has become denser and more complex, and the line spacing has become wider.

And he did not forget to inherit the natural descriptions of Japanese literature.

It appears that his connections to Kuji First High School (hereafter referred to as First High School), where he began his life in Tokyo, continued throughout his life.

The Guje High School automatically granted admission to Imperial University through the advancement guarantee system.

Since the first high school served as a preparatory course for Tokyo Imperial University (hereinafter referred to as Tokyo University), most of the students went on to Tokyo University.

So, strictly speaking, a friend from the University of Tokyo is also a friend from the first high school.

For example, Hideo Kobayashi was the author's senior from high school and a friend who, despite his harsh words, played a decisive role in restoring his honor.

Fujishima Toshio was a friend and a senior in the 8th class of the First High School Travel Club (the predecessor of the Mountaineering Club). He was the eldest to accompany him on his last mountain climb and witnessed his end.

Although Fukada loved mountains since childhood, it was also inevitable that he, a writer who had debuted separately, would focus solely on writing about mountains later in life.

The problems related to his private life ultimately gave rise to two genres of writers in the Japanese literary world: the mountain writer Fukada Kyuya and the children's literature writer Kitabatake Yaho (1903-1982).

Therefore, we cannot leave out the stories of his first wife, Kitabatake Yaho, and his second wife, Koba Shigeko.

Fukada said, “There are many locks in my heart, and I can open all of them except one.”

One thing about Yaho Kitabatake is that.

Yaho met Fukada when he was working in the editorial department of Kaizosha, as a selector for the award novel and as a submitting writer.

Fukada, who recognized Yaho's talent, visited her hometown of Aomori and met her, and that is how they became friends.

She suffered from spinal caries, which caused strong opposition from Fukada's family, but they began living together in the summer of 1929, and the poverty of those times is evidenced by the fact that when they moved to Kamakura, all they had was a cartload of luggage.

This was the so-called "Kamakura literati era," and writers began to gather in Kamakura, which was within commuting distance of Tokyo, which had been devastated by the Great Kanto Earthquake, and had convenient access to publishing houses. They were called the Kamakura literati.

Around this time, the novel Fukada published received favorable reviews from Yasunari Kawabata, his senior at his first high school and the University of Tokyo, and it seemed that he was rising to the ranks of promising writers.

This led to him dropping out of the university he had been attending and quitting his publishing job, all with just a brush to get back on his feet.

After Fukada's father passed away, he and Yaho became a formal couple in 1940, but in 1941, Fukada met Shigeko Koba, the older sister of critic Mitsuo Nakamura (real name Ichiro Koba), who was eight years younger than him and a friend from Daiichi High School and Tokyo University, at Nakamura's wedding reception, and they met again as if by fate.

Shigeko, who is five years younger than him, was Fukada's first love during his time at First High School, and he would run into her every day while wandering along the street at the time she was leaving school.

A month later, the two went together to Amakazariyama to climb from Otari Onsen as described in the text.

Fukada wrote about this time in “My Youth” saying, “Who would have thought that this coincidence would rule half my life!” and in “A Note on Falling to the City” included in “Kitaguni” he also wrote, “If this unexpected ambush (my current wife and my love story) had not been waiting for me in my life, I would still be living a carefree life as a Kamakura writer.”

After his defeat and his captivity, Fukada returned to Japan and did not stop by Kamakura, but instead went back to Yuzawa, where Shigeko and his eldest son Moritaro were.

When the marriage breaks down, Yaho goes around the neighborhood exposing Fukada for plagiarizing her manuscript.

Before this incident broke out, his senior Kawabata and friend Kobayashi, who lived in the neighborhood, noticed the plagiarism and gave Fukada generous advice to write his own work.

When Fukada published his short story collection “Tsugaru no Yadzura” and wrote a review that seemed to hint at his own shortcomings, saying, “I hope that such childish stories will not be caught by critics and will be loved by only a few people,” Kobayashi, who had been watching everything, wrote in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, “What kind of timid work is this author using to bring his youth to the world?

And he harshly rebuked him, saying, “This work is not the work of the author alone.”

The seven and a half years that Fukada spent leaving the literary world and living in his hometown of Daishoji and Kanazawa were truly difficult times, a time of self-pity and self-denial.

Without any excuses about his reputation, Fukada turned to being a literary figure in the mountains.

Regardless of how others viewed him, this was the time when his life as a man of letters was practically over. Fukada himself evaluated this as a time when he was selling his writings to the world.

After ending his seclusion and returning to Tokyo, he put his 'noble thoughts' into practice.

Any man of letters would have a thirst for books, but his passion for literature related to the Himalayas was so great that he himself called it pathological.

This obsession began after the French mountaineering team made their first ascent of Annapurna on June 3, 1950.

As the 8,000-meter Himalayan giants that Europe had challenged since before World War II began to fall one after another, he was inspired to introduce and translate literature about the Himalayas, the so-called "Abode of Snow."

When I saw that the complete 60-volume edition of the Alpine Club's journal, "Alpine Journal," was up for sale, I bought it for 120,000 yen, using almost all of the royalties I earned from "Himalaya Mountains and People," my first successful work after moving to Tokyo.

In order to obtain rare books about the Himalayas, I added 100,000 yen to the 200,000 yen prize money from the Yomiuri Literary Award for “One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan” and bought books I had seen at a literature exhibition held at Maruzen Bookstore.

It was a time when the starting salary for civil servants was 10,000 yen.

Moreover, Mrs. Shigeko would open the bills from Maruzen every time she bought books overseas, feeling anxious, but if the foreign books her husband had requested arrived, she would usually carry them back home, even if they were heavy.

At that time, the weight of the bookshelf made of stacked tangerine crates was so great that the floorboards in the house were about to break.

However, while he was in Daisetsuzan, Mrs. Shigeko built a two-pyeong (approximately 100 square meters) Kusansanbang (a mountain house with a name attached to it) for his Himalayan collection.

Fukada writes, “For a poor person like me, who doesn’t own a single share of stock, doesn’t have a time deposit, lives in a leaky house, and struggles to make ends meet at the end of the month, the only reason I was able to afford such a large payment was thanks to my wife’s support.”

In his book “Book Collection,” Omori Hisao writes about friends who bought expensive books but couldn’t say a word to their wives for three days, or who couldn’t bring them all home at once and left them at work to take them one at a time. However, Fukada himself says that he didn’t have such hardships.

The person who recommended “Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains” for the 16th Yomiuri Literary Award was none other than Kobayashi Hideo.

He, who was also a judge, wrote the reasons for his recommendation in the February 1st edition of the Yomiuri Shimbun (which was also the date the award was announced).

“In the review section, I recommended Fukada Kyuya’s ‘One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan.’

This is considered to be the most unique critical literature in recent times.

(…) The author says that just as people have personalities, mountains have mountain ranges.

It took the author 50 years of experience to gain a more confident critical perspective on mountaineering.

The sentence "秀逸" comes from him.

It was the author who taught me the beauty of the mountains.

(…) I would like to add, however presumptuously, that I was as happy as if it were my own work, as I received the approval of almost all the committee members for my recommendation.” Fukada said of this article, “I shed tears of my heart,” and in his acceptance speech in the February 6th issue of Comrade, he said, “It is the feet that do the work, not the pen.

“I never dreamed that I would receive a literary award for my writings on the mountain,” he said.

I believe that his ability to recover came from his cheerful and cheerful personality.

Unlike other violent superiors, he taught haiku to his subordinates even in the war. It is said that after the war, his former subordinates living in Noto, near his hometown, used haiku as a medium to help him in his seclusion.

A mountain that is good for reading and climbing

The translator concludes the preface by saying:

“I believe this book is not about a mountain that tempts a select few first-class climbers with stamina, skill, and courage, but is always ready to be kicked out. Rather, I believe it is about a mountain that whispers to everyone, inviting them to come, to open their eyes and walk along the mountain path, surrounded by the scent of the forest and listening to the birdsong.

Even if you don't go to the mountains, it would be nice to use it as a curation of famous mountains displayed in the long gallery that is the Japanese archipelago.

As long as there are Baekmyeongsan Mountains in Japan, and as long as people go hiking there, this is a book that will continue to be read.

The Korean edition of 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』, a legendary masterpiece among mountaineers, has been translated for the first time in half a century.

If you search for "Japan's 100 Famous Mountains" in the National Diet Library of Japan, 731 search results appear.

It is so famous that it is the origin of the trend of naming it 'What What Baekmyeongsan'.

This book was published in July 1964, and now even the author's identity has faded, so most people only get a rough idea of it from the materials distributed in advance by travel agencies planning Baekmyeongsan tours.

But now it should be called Fukada Kyuya's "One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan."

On the other hand, among professional mountaineers and mountaineering enthusiasts, 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』 is a standard of authority to support their experiences and claims.

In other words, it is no exaggeration to say that the term Baekmyeongsan has become a hashtag for almost all mountaineering-related content in Japan.

Today, mountaineers in Japan rarely fail to quote a few lines from "One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan" in their communities or blogs.

Additionally, Baekmyeongsan is mentioned without fail in promotional materials for the region, reports and papers by local researchers, and even in matters related to local community organizations.

The same goes for derivative products such as maps, guidebooks, and tour programs, not to mention the accommodations the author stayed in before and after the hike.

Borrowing from the pens of many critics, this book, "100 Famous Mountains of Japan," commonly referred to as the "Bible of Mountains," is an essay on 100 mountains across Japan selected by the author based on their dignity, history, individuality, and heights of over 1,500 meters.

It includes various Japanese traditions by mentioning Japanese mountaineering history and literature in the form of Sanmyeonggo.

However, the mountains described in this book are 60 years old since its publication and 100 years old since the author's mountaineering activities. Nowadays, most mountains have ropeways and automobile roads that reach the top of the mountain, so it seems as if the spirit of the mountain has lost its place to reside.

Many of the facilities that were built on the mountainside during the boom times have now turned into ruins.

In other words, it is difficult to expect the scenery that the mountain had at that time, so this book is insufficient as a guidebook to the 100 famous mountains of Japan that were once leisurely.

Still, it will still be a useful reference for those who actually plan to travel or hike here, and anyone curious about Japanese culture will find plenty of stories to enjoy as a bonus.

Hear directly from the author about the background behind the selection of Baekmyeongsan Mountain.

Japan is a country of mountains.

No matter where you go, there is no place where you cannot see mountains.

There is a handsome mountain overlooking the city, town, and village, and it has an atmosphere that is always included in the school song there.

Most Japanese people grew up seeing mountains.

Although Tokyo is far from mountains, in the past when there was less pollution, Mount Fuji and Mount Tsukuba were important backdrops to the city.

All of the hundred famous mountains listed in this book are mountains the author has stood on top of.

Since I had to choose a hundred, I had to climb several mountains.

In selecting the 100 mountains, the author first set three criteria.

The first is the dignity of the mountain.

It should be a mountain that anyone who sees it would admire as a great mountain.

Even if you pass the exam in terms of height, you won't choose an ordinary mountain.

A mountain that does not have something that touches the human heart, whether it be ruggedness, strength, or beauty, is not smooth.

Just as people have different levels of character, mountains also have different levels of character.

It must be a mountain with a mountain range, not a personality.

Second, the author says he respects the history of the mountain.

We cannot exclude mountains that have had a deep connection with humans since ancient times.

A mountain that people look up to and revere morning and night, and that deserves to have a shrine built on its summit, naturally qualifies as a famous mountain.

The spirit of the mountain resides there.

However, the recent development of the strange tourism industry has commercialized famous mountains with long histories, and the spirit of the mountains has also lost its place to reside.

You can't choose a mountain like that.

The third is a mountain with personality.

Just like works of art, something with a distinct personality attracts attention.

The author respects the uniqueness that only a mountain possesses, whether it be its form, its phenomenon, or its tradition, that cannot be found anywhere else.

The ordinary mountains that are everywhere are not smooth.

Of course, not all mountains are the same shape and each has its own characteristics, but it is the strong individuality among them that draws me in.

As an additional condition, a line of approximately 1500 meters was drawn.

A mountain is not necessarily noble because it is tall, but it must be of a certain height to fall into the category of mountains the author is aiming for.

For example, Mount Yahiko in Echigo, Mount Hiei in Kyoto, and Mount Hiko in Bungo are undoubtedly famous mountains that have been famous since ancient times, but they are very short.

There are exceptions.

Mount Tsukuba and Mount Kaimondake.

The author wrote in the text why he chose it.

Specifically, nine peaks were mentioned in Hokkaido, but other strong candidates include Upepesanke, Nipesosu, Ishikari, Petegari, Ashibetsu, Komagatake, and Tarumaesan.

However, it was excluded for the unfair reason that the author only looked at the mountains and did not actually climb them.

The author says there is no excuse for this.

In the Tohoku region, Akita Komagatake and Kurikomayama should have been included.

Although Mt. Moriyoshi, Mt. Himekami, and Mt. Funagata are good mountains, they are a bit short in height.

The thing the author hesitated about the most was the use of Chosin.

There were plenty of second-class, if not first-class, heights here.

Besides, they are all mountains the author likes.

There are many mountains that would not be out of place among the 100 famous mountains, such as Nyoho-san, Sen-no-kura-san, Kurohime-san, Iizuna-san, Sumon-san, Arasawa-dake, Shirasuna-san, Torikabuto-san, Iwasuge-san, and others.

People often ask Kyuya Fukuda which mountain he likes best.

The author's answer to this question is always set.

This is the most recent mountain I visited.

Because the impression of that mountain is vivid.

Perhaps the mountain I mentioned above as an example would have been included in Baekmyeongsan if I had just returned from there.

It is inevitable that the mountains of the Japanese Alps occupy more than a quarter of the Baekmyeongsan Mountains.

This place, which forms the backbone of Honshu, is quickly over thirty in number just by counting the things that stand out.

The choice among them also puzzled the author.

The mountains that should have been chosen naturally were Yukikura-dake, Okudainichi-dake, Harinoki-dake, Rengedake, Tsubakuro-dake, Otenjo-dake, Kasumizawa-dake, Ariake-yama, Kaki-dake, and Kekachi-dake.

In the south, I also wanted to include Daimugenyama, Jarugatake, and Shichimenzan.

In Hokuriku, I was determined to include Mount Oizurugatake and Mount Ogasayama in the Hakusan Mountain Range.

This is not just because it is the author's hometown mountain, but because he wanted to spread the word to the world that such a wonderful, hidden mountain exists.

However, I regret to say that I have omitted it as I have not yet had the opportunity to climb it.

In addition to Ibukiyama, Odaigaharayama, and Omineyama, which I chose from Kansai, I also wanted to include Suzukayama and Hirayama, which have been famous since ancient times.

I've been to Suzukayama three times.

However, Mount Gozaisho had already become an amusement park, and when he climbed Mount Fujiwaradake and looked out at the mountains of Suzuka, the author hesitated because none of them were high.

Chugoku lacks high mountains.

The day I climbed Hoki Daisen was an exceptionally clear autumn day, and from its summit I gazed upon the spine mountain range that divides Sanyo and Sanin.

My expectation was that there would be a mountain of some kind somewhere.

However, the mountains that were connected in several layers were all flat hills, so there was nothing particularly eye-catching.

I also stopped by Hiruzen, but it was not enough to recommend it as a famous mountain.

I went west again and climbed Mt. Sanbe.

From there, I looked out at the mountains of Nishi-Chugoku.

The result was the same.

The search for famous mountains ended in vain.

In this way, Daisen became one in Chugoku.

If I had to pick one, it would probably be Hyonosen.

The author says that there is no dispute about the two peaks of Shikoku, Mount Ishizuchi and Mount Tsurugi.

Kyushu chose six peaks, and I also had Mount Yufu, Mount Ichifusa, and Mount Sakurajima in mind.

They are all wonderful mountains with their own unique characteristics.

Translation Background and Key Considerations

There were Japanese mountaineers who were often the topic of conversation at after-parties at the group the translator belonged to.

It started with the opening remarks of Professor Kim Young-do (1924-2023).

For example, people like Kogure Ritaro, Tanabe Juji, Oshima Ryokichi, who appear in the main text, and Kushida Magoichi, who wrote the commentary for this book at the end, and Professor Fukada Kyuya were also regulars.

All of them appeared in pairs with their works.

In the sense that everyone has heard of classics, but few have read them, 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』 was no exception, and everyone seemed more curious about the contents than any other book.

Mr. Kim Young-do led the construction of 35 mountain lodges across the country, which began in 1970, and he served as the leader of the 1977 Everest expedition, the first Korean to reach the summit, led by Mr. Ko Sang-don, and the leader of the 1978 Arctic expedition.

Afterwards, he founded the Korea Mountaineering Research Institute, translated several mountaineering books from Gumi, and studied mountaineering history.

One day, the translator asked Mr. Kim Young-do what Japanese mountain book he considered a masterpiece.

After hearing the answer, “『Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains』 is the best,” the translator asked, “Then, would it be okay if you translated it?”

“Because it is such a difficult book to put into words...” was the answer at the time.

As time went by and the translator translated this book, he was able to understand what the words meant.

One day, Kim Jin-deok, a member of the same group as the translator, suggested that we create a small group and read Japanese Shanxi books.

He also said that there is no other book that has had as much influence in Korea and Japan as 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』, and expressed regret that 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』 has not yet been translated.

The translator, who had always been interested in the history of mountaineering in Japan, which is inevitably related to the history of mountaineering in Korea since the modern era, and who knew a little about the mountains of Hokkaido, suggested that we proofread 『One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan』 without much thought, but because he was curious about the content, he ended up taking on the translation himself, which expanded the work.

That doesn't mean the translator had much experience mountaineering in Japan.

If I hadn't received a few responses from friends expressing interest in the rest of the content after translating a few of the Hokkaido mountains that appear in the first part of "One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan," I might have quickly given up on the delusion of wanting to translate the entire work.

As the translation work moved to Honshu, it began to sink into the swamp of Japan's unique diversity.

Sanmyeonggo was beginning to reveal its true colors.

Stories about mountains all over Japan were intertwined, as if they were being spoken in the dialects of each of the eight provinces.

Moreover, because the author himself wrote with the principle of having five 400-character manuscript pages per chapter, the book was surprisingly vast when unzipped.

For example, there is a place name called Nakaguchi that appears in the 'Arashimadake' section.

This can be read in various ways, but finding a local reading was difficult, and not wanting to be vague, the translator personally looked up road signs in the area and found that it is read as 'Nakande'.

This book, based on the first edition, is a 26-centimeter hardcover book with 222 pages, each containing a small map and a photograph.

Since this book is not a product of imagination but deals with facts and historical facts, I decided to carefully examine and explain the unfamiliar points that appear in the book.

The footnotes in the text are intended to reflect a range of perspectives.

Japanese cultural history is difficult to interpret with a single, defined concept because it contains many exceptional elements, and there are many parts where it is difficult to find a logical structure that presupposes regularity.

Therefore, I do not believe that the translation has universality and it is natural that it may convey contradictory or insufficient information.

However, in order to increase objectivity, we tried not to quote anything without a source other than the translator's opinion.

In addition to referencing books and papers, I also accessed digital resources from public libraries in Japan.

In Japanese encyclopedias, I checked and referenced only the articles with authors listed, and in Japanese Wikipedia, which has a vast amount of data but also contains incorrect information, I only checked and referenced the parts with sources.

Each country has developed its own unique language to express nature or natural phenomena from early on.

However, people today who are accustomed to city life have less opportunity to experience and describe in detail the changes in weather and terrain as people in the past did, so expressions related to these may feel unfamiliar.

However, since it is an essential element in articles dealing with mountaineering, I first collected forgotten Korean words related to it and adopted them appropriately based on my experience climbing Korean and Japanese mountains.

I consulted several maps to confirm the parts related to the description of the terrain. I grasped the overall terrain through the detailed map of the Geographical Survey Institute of Japan (Electronic National Land Web), and I used commercially available bird's-eye views and mountaineering maps to determine the approach.

We checked the hiking trail, the actual shape of the mountain, its relationship with the surrounding terrain, and whether facilities or structures were still in existence.

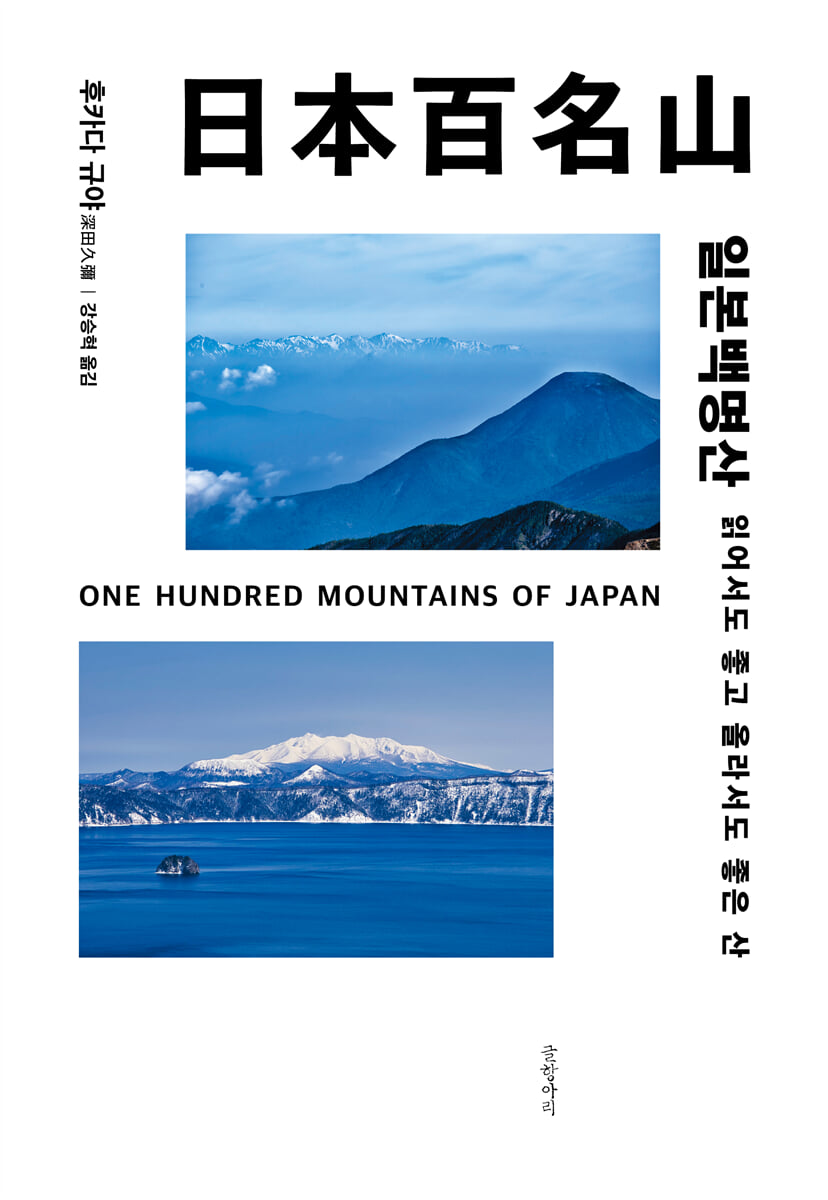

I want to talk about photography.

There were many difficulties in selecting the photos to include in the text.

In order to capture the characteristics of the mountain, I had no choice but to choose a photo that contained the entirety of the mountain.

Also, to explain in captions, you need to know where the photo was taken and from.

In the end, I had no choice but to follow the gaze of other climbers who had chosen that route, and in the process, I passed by so many beautiful places that I wanted to see and that were too precious to just take in with my eyes, that those words struck me anew.

However, it is realistically difficult to reveal all of the mountain's expressions on the page of the text.

Anyway, I tried to select all the photos that were most relevant to the content of the text.

However, there were many regrettable moments when there were not suitable photos in all the necessary places, and when luck did not follow the photographer's will to capture the decisive scene while climbing the rugged mountain.

So, of course, there are some photos that are not well-made or not very good, so I don't think we can judge the beauty of the mountain based on that alone.

Rather, I hesitated, fearing that these few photos, which are nothing more than mere glimpses of the mountain, would not only shatter the illusion of the famous mountain but also plant false preconceptions. However, in the end, the translator, who must know the contents of the book best, chose to include them.

About the life of Kyuya Fukuda

『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』 largely overlaps in subject matter and content with several essays on mountains that the author has previously published.

That is, the author wrote several essays about the same mountain.

In this way, the author spent a long time preparing 『Japan's 100 Famous Mountains』, refining and polishing the text.

Thanks to this, the texture of this book has become denser and more complex, and the line spacing has become wider.

And he did not forget to inherit the natural descriptions of Japanese literature.

It appears that his connections to Kuji First High School (hereafter referred to as First High School), where he began his life in Tokyo, continued throughout his life.

The Guje High School automatically granted admission to Imperial University through the advancement guarantee system.

Since the first high school served as a preparatory course for Tokyo Imperial University (hereinafter referred to as Tokyo University), most of the students went on to Tokyo University.

So, strictly speaking, a friend from the University of Tokyo is also a friend from the first high school.

For example, Hideo Kobayashi was the author's senior from high school and a friend who, despite his harsh words, played a decisive role in restoring his honor.

Fujishima Toshio was a friend and a senior in the 8th class of the First High School Travel Club (the predecessor of the Mountaineering Club). He was the eldest to accompany him on his last mountain climb and witnessed his end.

Although Fukada loved mountains since childhood, it was also inevitable that he, a writer who had debuted separately, would focus solely on writing about mountains later in life.

The problems related to his private life ultimately gave rise to two genres of writers in the Japanese literary world: the mountain writer Fukada Kyuya and the children's literature writer Kitabatake Yaho (1903-1982).

Therefore, we cannot leave out the stories of his first wife, Kitabatake Yaho, and his second wife, Koba Shigeko.

Fukada said, “There are many locks in my heart, and I can open all of them except one.”

One thing about Yaho Kitabatake is that.

Yaho met Fukada when he was working in the editorial department of Kaizosha, as a selector for the award novel and as a submitting writer.

Fukada, who recognized Yaho's talent, visited her hometown of Aomori and met her, and that is how they became friends.

She suffered from spinal caries, which caused strong opposition from Fukada's family, but they began living together in the summer of 1929, and the poverty of those times is evidenced by the fact that when they moved to Kamakura, all they had was a cartload of luggage.

This was the so-called "Kamakura literati era," and writers began to gather in Kamakura, which was within commuting distance of Tokyo, which had been devastated by the Great Kanto Earthquake, and had convenient access to publishing houses. They were called the Kamakura literati.

Around this time, the novel Fukada published received favorable reviews from Yasunari Kawabata, his senior at his first high school and the University of Tokyo, and it seemed that he was rising to the ranks of promising writers.

This led to him dropping out of the university he had been attending and quitting his publishing job, all with just a brush to get back on his feet.

After Fukada's father passed away, he and Yaho became a formal couple in 1940, but in 1941, Fukada met Shigeko Koba, the older sister of critic Mitsuo Nakamura (real name Ichiro Koba), who was eight years younger than him and a friend from Daiichi High School and Tokyo University, at Nakamura's wedding reception, and they met again as if by fate.

Shigeko, who is five years younger than him, was Fukada's first love during his time at First High School, and he would run into her every day while wandering along the street at the time she was leaving school.

A month later, the two went together to Amakazariyama to climb from Otari Onsen as described in the text.

Fukada wrote about this time in “My Youth” saying, “Who would have thought that this coincidence would rule half my life!” and in “A Note on Falling to the City” included in “Kitaguni” he also wrote, “If this unexpected ambush (my current wife and my love story) had not been waiting for me in my life, I would still be living a carefree life as a Kamakura writer.”

After his defeat and his captivity, Fukada returned to Japan and did not stop by Kamakura, but instead went back to Yuzawa, where Shigeko and his eldest son Moritaro were.

When the marriage breaks down, Yaho goes around the neighborhood exposing Fukada for plagiarizing her manuscript.

Before this incident broke out, his senior Kawabata and friend Kobayashi, who lived in the neighborhood, noticed the plagiarism and gave Fukada generous advice to write his own work.

When Fukada published his short story collection “Tsugaru no Yadzura” and wrote a review that seemed to hint at his own shortcomings, saying, “I hope that such childish stories will not be caught by critics and will be loved by only a few people,” Kobayashi, who had been watching everything, wrote in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, “What kind of timid work is this author using to bring his youth to the world?

And he harshly rebuked him, saying, “This work is not the work of the author alone.”

The seven and a half years that Fukada spent leaving the literary world and living in his hometown of Daishoji and Kanazawa were truly difficult times, a time of self-pity and self-denial.

Without any excuses about his reputation, Fukada turned to being a literary figure in the mountains.

Regardless of how others viewed him, this was the time when his life as a man of letters was practically over. Fukada himself evaluated this as a time when he was selling his writings to the world.

After ending his seclusion and returning to Tokyo, he put his 'noble thoughts' into practice.

Any man of letters would have a thirst for books, but his passion for literature related to the Himalayas was so great that he himself called it pathological.

This obsession began after the French mountaineering team made their first ascent of Annapurna on June 3, 1950.

As the 8,000-meter Himalayan giants that Europe had challenged since before World War II began to fall one after another, he was inspired to introduce and translate literature about the Himalayas, the so-called "Abode of Snow."

When I saw that the complete 60-volume edition of the Alpine Club's journal, "Alpine Journal," was up for sale, I bought it for 120,000 yen, using almost all of the royalties I earned from "Himalaya Mountains and People," my first successful work after moving to Tokyo.

In order to obtain rare books about the Himalayas, I added 100,000 yen to the 200,000 yen prize money from the Yomiuri Literary Award for “One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan” and bought books I had seen at a literature exhibition held at Maruzen Bookstore.

It was a time when the starting salary for civil servants was 10,000 yen.

Moreover, Mrs. Shigeko would open the bills from Maruzen every time she bought books overseas, feeling anxious, but if the foreign books her husband had requested arrived, she would usually carry them back home, even if they were heavy.

At that time, the weight of the bookshelf made of stacked tangerine crates was so great that the floorboards in the house were about to break.

However, while he was in Daisetsuzan, Mrs. Shigeko built a two-pyeong (approximately 100 square meters) Kusansanbang (a mountain house with a name attached to it) for his Himalayan collection.

Fukada writes, “For a poor person like me, who doesn’t own a single share of stock, doesn’t have a time deposit, lives in a leaky house, and struggles to make ends meet at the end of the month, the only reason I was able to afford such a large payment was thanks to my wife’s support.”

In his book “Book Collection,” Omori Hisao writes about friends who bought expensive books but couldn’t say a word to their wives for three days, or who couldn’t bring them all home at once and left them at work to take them one at a time. However, Fukada himself says that he didn’t have such hardships.

The person who recommended “Japan’s 100 Famous Mountains” for the 16th Yomiuri Literary Award was none other than Kobayashi Hideo.

He, who was also a judge, wrote the reasons for his recommendation in the February 1st edition of the Yomiuri Shimbun (which was also the date the award was announced).

“In the review section, I recommended Fukada Kyuya’s ‘One Hundred Famous Mountains of Japan.’

This is considered to be the most unique critical literature in recent times.

(…) The author says that just as people have personalities, mountains have mountain ranges.

It took the author 50 years of experience to gain a more confident critical perspective on mountaineering.

The sentence "秀逸" comes from him.

It was the author who taught me the beauty of the mountains.

(…) I would like to add, however presumptuously, that I was as happy as if it were my own work, as I received the approval of almost all the committee members for my recommendation.” Fukada said of this article, “I shed tears of my heart,” and in his acceptance speech in the February 6th issue of Comrade, he said, “It is the feet that do the work, not the pen.

“I never dreamed that I would receive a literary award for my writings on the mountain,” he said.

I believe that his ability to recover came from his cheerful and cheerful personality.

Unlike other violent superiors, he taught haiku to his subordinates even in the war. It is said that after the war, his former subordinates living in Noto, near his hometown, used haiku as a medium to help him in his seclusion.

A mountain that is good for reading and climbing

The translator concludes the preface by saying:

“I believe this book is not about a mountain that tempts a select few first-class climbers with stamina, skill, and courage, but is always ready to be kicked out. Rather, I believe it is about a mountain that whispers to everyone, inviting them to come, to open their eyes and walk along the mountain path, surrounded by the scent of the forest and listening to the birdsong.

Even if you don't go to the mountains, it would be nice to use it as a curation of famous mountains displayed in the long gallery that is the Japanese archipelago.

As long as there are Baekmyeongsan Mountains in Japan, and as long as people go hiking there, this is a book that will continue to be read.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 27, 2025

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 768 pages | 140*200*40mm

- ISBN13: 9791169094443

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)