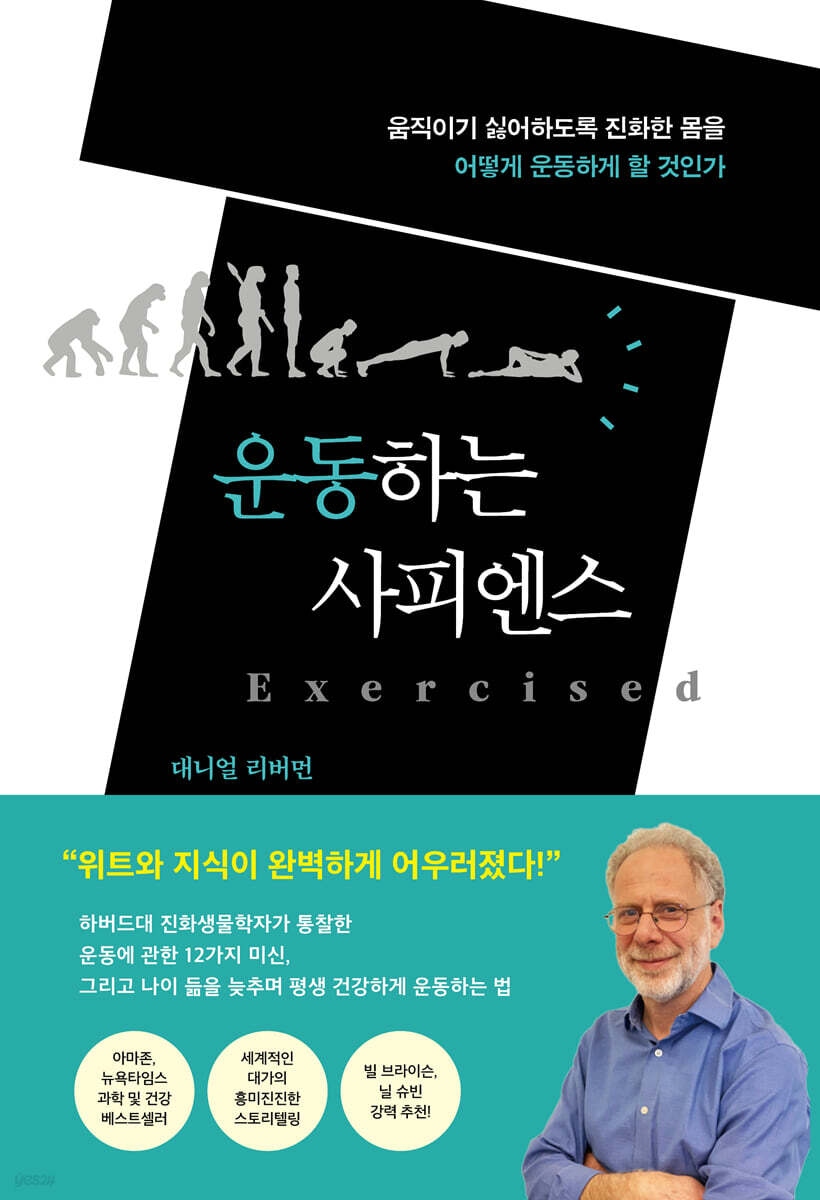

Sapiens exercising

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

- The reason why buying a one-year gym membership is risky is because most of us only go to the gym a few times.

I don't feel like moving my body.

Daniel Lieberman, professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University, explains why humans evolved this way and how to overcome the temptation to be lazy.

- Son Min-gyu, natural science producer

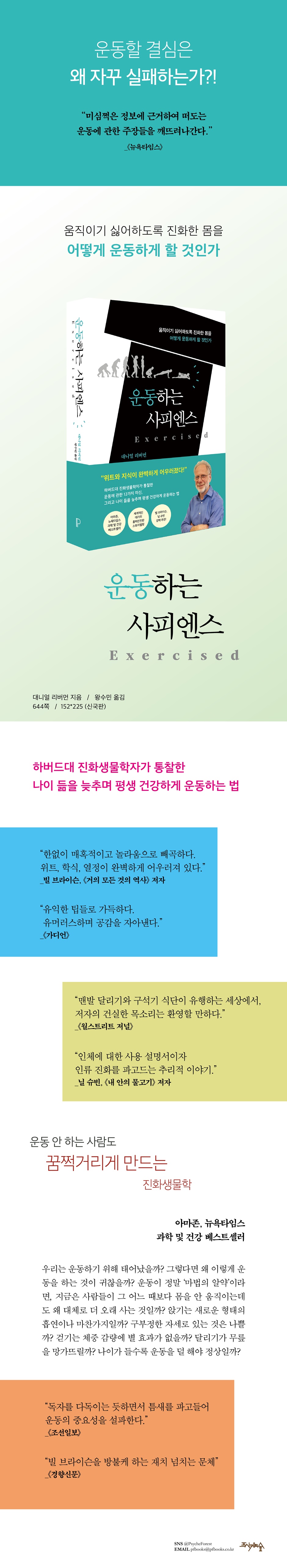

Why Do My Resolutions to Exercise Keep Fail?

Evolutionary biology that makes even non-exercisers squirm

It is common knowledge that exercise is good for your health.

But why is exercise so tiresome? If exercise truly is a "magic pill," why do people live longer today, despite being more sedentary than ever before? Does running actually cause knee problems? Is sitting necessarily bad for your health? Does walking help you lose weight? Is it normal to move less as you age?

Daniel Lieberman, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University and a pioneering researcher on the evolution of human physical activity, delves into the contradictory and unsettling information about exercise.

He presents twelve exercise-related superstitions and clearly explains various human physical activities that have not been well explained until now, based on insights from evolutionary biology and anthropology.

It's full of useful information, including how certain exercises are effective for various diseases, whether walking 10,000 steps is really good for your health, and how to do weight training and aerobic exercise.

This book, a blend of the author's extensive field experience, meticulous research knowledge, wit, and liveliness, will immediately move readers.

Evolutionary biology that makes even non-exercisers squirm

It is common knowledge that exercise is good for your health.

But why is exercise so tiresome? If exercise truly is a "magic pill," why do people live longer today, despite being more sedentary than ever before? Does running actually cause knee problems? Is sitting necessarily bad for your health? Does walking help you lose weight? Is it normal to move less as you age?

Daniel Lieberman, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University and a pioneering researcher on the evolution of human physical activity, delves into the contradictory and unsettling information about exercise.

He presents twelve exercise-related superstitions and clearly explains various human physical activities that have not been well explained until now, based on insights from evolutionary biology and anthropology.

It's full of useful information, including how certain exercises are effective for various diseases, whether walking 10,000 steps is really good for your health, and how to do weight training and aerobic exercise.

This book, a blend of the author's extensive field experience, meticulous research knowledge, wit, and liveliness, will immediately move readers.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Prologue: Why Exercise Is Good for Your Health, But We Don't Want to Do It

Chapter 1: Are we really born to run?

In search of a primitive tribe of marathon runners

Larahipari under the twinkling stars

The myth of the athletic savage

If possible, take it easy

If you walk for just one hour

How Exercise Became So Strange

Part 1 Inactivity

Chapter 2: The Importance of Laziness

The cost of doing nothing

Minnesota Starvation Experiment

The Truth About Barter

Are humans born lazy?

The best thing is to not move

Chapter 3: Sitting: A New Form of Smoking?

Backrest chair addiction

How many hours a day do we sit?

Light a fire inside

If you continue to sit still like that

How to sit healthily

Is standing at work really good for your health?

Chapter 4: Sleep: Why Stress Interferes with Rest

Did sleep really evolve for rest?

The unfounded belief that it takes 8 hours

Sleep as a private life, sleep as a social life

Stress caused by insomnia

Beyond excessive worry

Part 2: Speed, Strength, and Power

Chapter 5 Speed: Neither the Tortoise nor the Hare

How slow is Usain Bolt?

Two-legged obstacle

Run fast, run far

The difference between red and white muscles

Is athletic talent inherited?

Have both endurance and speed

Chapter 6: Strength: From lean to muscular

Far from excessive muscle

Apes and cavemen of monstrous strength?

Do you have to exercise until your body aches?

aging muscles

Just the right amount of strength

Chapter 7: Fighting and Sports: From Fangs to Football

Are humans born aggressive?

Murderer vs. Collaborator

The better angels among the genus Homo

Fighting with bare hands

Fight with weapons

The evolution of sports

Part 3 Endurance

Chapter 8: Walking: A Daily Routine

How do we walk?

From knuckle walking to upright walking

beasts of burden

No matter how much I walk

About walking ten thousand steps

Chapter 9 Running and Dancing: Jumping from Leg to Leg

The battle between man and horse

evolved to run

Carcass scavenging and persistent hunting

How to run well without injury

Shall We Dance

Chapter 10: Endurance and Aging: Active Grandparents and the Expensive Maintenance Hypothesis

Why Grandma and Grandpa are so hard-working

Getting older but avoiding aging

Why Exercise Is Good for Your Health

To live a long life without disease

Part 4 How to Exercise

Chapter 11: How to Get Exercise into Your Body: To Move or Not to Move

A company where regular exercise is a working condition

I don't really want to do it

I feel good when I exercise like this.

Gentle intervention and rough intervention

Students deprived of exercise

Chapter 12 What kind of exercise and how much?

150 minutes a week?

Concerns about excessive exercise

Mix up different exercises

Chapter 13 Exercise and Disease

obesity

Metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes

cardiovascular disease

Other infectious diseases including respiratory infections

chronic musculoskeletal disorders

cancer

Alzheimer's disease

depression and anxiety

Epilogue: It's never too late to exercise.

Chapter 1: Are we really born to run?

In search of a primitive tribe of marathon runners

Larahipari under the twinkling stars

The myth of the athletic savage

If possible, take it easy

If you walk for just one hour

How Exercise Became So Strange

Part 1 Inactivity

Chapter 2: The Importance of Laziness

The cost of doing nothing

Minnesota Starvation Experiment

The Truth About Barter

Are humans born lazy?

The best thing is to not move

Chapter 3: Sitting: A New Form of Smoking?

Backrest chair addiction

How many hours a day do we sit?

Light a fire inside

If you continue to sit still like that

How to sit healthily

Is standing at work really good for your health?

Chapter 4: Sleep: Why Stress Interferes with Rest

Did sleep really evolve for rest?

The unfounded belief that it takes 8 hours

Sleep as a private life, sleep as a social life

Stress caused by insomnia

Beyond excessive worry

Part 2: Speed, Strength, and Power

Chapter 5 Speed: Neither the Tortoise nor the Hare

How slow is Usain Bolt?

Two-legged obstacle

Run fast, run far

The difference between red and white muscles

Is athletic talent inherited?

Have both endurance and speed

Chapter 6: Strength: From lean to muscular

Far from excessive muscle

Apes and cavemen of monstrous strength?

Do you have to exercise until your body aches?

aging muscles

Just the right amount of strength

Chapter 7: Fighting and Sports: From Fangs to Football

Are humans born aggressive?

Murderer vs. Collaborator

The better angels among the genus Homo

Fighting with bare hands

Fight with weapons

The evolution of sports

Part 3 Endurance

Chapter 8: Walking: A Daily Routine

How do we walk?

From knuckle walking to upright walking

beasts of burden

No matter how much I walk

About walking ten thousand steps

Chapter 9 Running and Dancing: Jumping from Leg to Leg

The battle between man and horse

evolved to run

Carcass scavenging and persistent hunting

How to run well without injury

Shall We Dance

Chapter 10: Endurance and Aging: Active Grandparents and the Expensive Maintenance Hypothesis

Why Grandma and Grandpa are so hard-working

Getting older but avoiding aging

Why Exercise Is Good for Your Health

To live a long life without disease

Part 4 How to Exercise

Chapter 11: How to Get Exercise into Your Body: To Move or Not to Move

A company where regular exercise is a working condition

I don't really want to do it

I feel good when I exercise like this.

Gentle intervention and rough intervention

Students deprived of exercise

Chapter 12 What kind of exercise and how much?

150 minutes a week?

Concerns about excessive exercise

Mix up different exercises

Chapter 13 Exercise and Disease

obesity

Metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes

cardiovascular disease

Other infectious diseases including respiratory infections

chronic musculoskeletal disorders

cancer

Alzheimer's disease

depression and anxiety

Epilogue: It's never too late to exercise.

Detailed image

Into the book

Everyone knows that you should exercise, but there's nothing more annoying than hearing people tell you that you should exercise this much.

If exercise is so natural and should be done, why, after all these years, has no one found an effective way to help more people overcome their deep-rooted natural instinct to resist exertion?

--- p.18

These apes, our closest relatives, spend most of their days lazing around, as if observing a never-ending Sabbath.

Hunter-gatherers like the Hadza, who don't do extremely strenuous work and spend a significant portion of their days doing little physical activity, appear to be workaholics compared to apes.

--- p.66

As I've said many times, sitting in a comfortable chair puts almost no strain on your muscles.

On the other hand, squatting or kneeling requires some muscle effort, and simply standing burns 8 more calories per hour than sitting, and light activities like folding laundry can burn as much as 100 calories per hour more.

These calories add up.

Just five hours of low-intensity, "non-exercise" physical activity a day can burn as much energy as running for an hour.

--- p.118

Even light activities like occasional movement while sitting, or even activities that require muscle strength like squatting or kneeling, lower blood fat and sugar levels more than sitting passively for long periods of time.

--- p.119

Their sleep time was actually shorter than that of people in industrial societies.

During warmer months, these wild foragers sleep an average of 5.7 to 6.5 hours per night, while during colder months, they sleep an average of 6.6 to 7.1 hours per night.

Not only that, they hardly ever took naps.

Contrary to what we often hear, there is no evidence that people in non-industrial societies sleep more than people in industrial or post-industrial societies.

--- p.150

Humans appear to have adapted to sleep less than our ape relatives, including chimpanzees.

Our ancestors slept lightly, reduced their sleep to a minimum, and each member took turns sleeping deeply, with at least one person in the group always waking up to sound the alarm in times of danger. If this had not been the case, our ancestors, who were particularly weak, might have gone extinct long ago.

--- p.153

Our society tends to make judgments about whether or not we move our bodies.

It's like labeling sitting as bad and sleeping as good.

In reality, both of these relaxation strategies are perfectly normal, yet highly variable, behaviors with complex costs and benefits, and are strongly influenced by our surroundings and contemporary cultural norms.

--- p.169

Most of us are stronger than we think, but we never fully utilize our strength.

This is because our nervous system is smart enough to prevent us from going all out, which could tear our muscles, break our bones, or even endanger our lives.

--- p.229

Older hunter-gatherers and those who remain active throughout their lives are living proof that using muscles can help prevent muscle loss as we age.

It's not that getting older doesn't mean your muscles' ability to respond to resistance exercise ends.

In fact, if you occasionally do resistance training at a slow pace, you can reverse muscle loss regardless of age.

--- p.235

The most common area of injury when running is the knees.

I can't even count how many times I've met people (including doctors) who complained that their knees were out because they ran too much.

Does running really cause so many injuries? If we evolved to run long distances, why aren't our bodies better adapted to it?

--- p.358

I've been racking my brain for decades trying to explain why our ancestors developed so many adaptations for running such incredibly long distances.

The only plausible answer I can come up with is that it was to get my hands on meat.

--- p.350

One similarity between running and dancing that few people think about is how they transport us to another dimension.

Long, intense workouts stimulate the release of feel-good chemicals in the brain, including opioids, endorphins, and, most importantly, endocannabinoids, which are similar to the active compounds in marijuana.

That's why people who run or dance feel a heightened sense of well-being.

--- p.373

According to this theory, these diligent and helpful grandparents, who were blessed with genes that favored longevity while caring for others, had more children and grandchildren, thus passing on their genes to their descendants.

It is clear that as time goes by, humans have been selected to live longer, be more tolerant, and be useful grandparents to those around them.

--- p.383

If exercise is so damaging to the body, why is it considered good for your health? The reason is that after she stopped exercising, her body responded in a unique way, not only repairing all the damage caused by exercise, but, most importantly, even repairing some of the damage incurred when she wasn't exercising.

--- p.399

As it turns out, skipping exercise, even when you're pressed for time, can sometimes make you less productive.

Randomized controlled studies of college students confirm that much of what we already instinctively know is true.

In other words, even just briefly engaging in moderate to high intensity exercise can improve memory and concentration.

--- p.455

Ultimately, each of us is an "experiment" with different preferences based on our backgrounds, goals, and age, so there may not be an optimal combination of exercise types, just as there may not be an optimal amount of exercise.

So, although exercise may be a somewhat bizarre modern behavior, from an evolutionary perspective, we still recommend the same level of physical activity that people have been doing for centuries, albeit with different terminology.

That means working out a few hours a week, focusing on cardio and some weight training, and continuing to do so even as you get older.

--- p.486

If we simply follow that ancient, deep-rooted instinct to avoid the discomfort of physical exertion, we will not only age faster and increase our chances of dying younger, but we will also become more susceptible to numerous diseases and chronic, disabling conditions.

Along with this, you will forever miss the opportunity to live a life full of energy that comes with being strong in both body and mind.

Given our evolutionary history, a lifetime of physical activity dramatically increases our chances of living a healthy life and dying after 70 years.

If exercise is so natural and should be done, why, after all these years, has no one found an effective way to help more people overcome their deep-rooted natural instinct to resist exertion?

--- p.18

These apes, our closest relatives, spend most of their days lazing around, as if observing a never-ending Sabbath.

Hunter-gatherers like the Hadza, who don't do extremely strenuous work and spend a significant portion of their days doing little physical activity, appear to be workaholics compared to apes.

--- p.66

As I've said many times, sitting in a comfortable chair puts almost no strain on your muscles.

On the other hand, squatting or kneeling requires some muscle effort, and simply standing burns 8 more calories per hour than sitting, and light activities like folding laundry can burn as much as 100 calories per hour more.

These calories add up.

Just five hours of low-intensity, "non-exercise" physical activity a day can burn as much energy as running for an hour.

--- p.118

Even light activities like occasional movement while sitting, or even activities that require muscle strength like squatting or kneeling, lower blood fat and sugar levels more than sitting passively for long periods of time.

--- p.119

Their sleep time was actually shorter than that of people in industrial societies.

During warmer months, these wild foragers sleep an average of 5.7 to 6.5 hours per night, while during colder months, they sleep an average of 6.6 to 7.1 hours per night.

Not only that, they hardly ever took naps.

Contrary to what we often hear, there is no evidence that people in non-industrial societies sleep more than people in industrial or post-industrial societies.

--- p.150

Humans appear to have adapted to sleep less than our ape relatives, including chimpanzees.

Our ancestors slept lightly, reduced their sleep to a minimum, and each member took turns sleeping deeply, with at least one person in the group always waking up to sound the alarm in times of danger. If this had not been the case, our ancestors, who were particularly weak, might have gone extinct long ago.

--- p.153

Our society tends to make judgments about whether or not we move our bodies.

It's like labeling sitting as bad and sleeping as good.

In reality, both of these relaxation strategies are perfectly normal, yet highly variable, behaviors with complex costs and benefits, and are strongly influenced by our surroundings and contemporary cultural norms.

--- p.169

Most of us are stronger than we think, but we never fully utilize our strength.

This is because our nervous system is smart enough to prevent us from going all out, which could tear our muscles, break our bones, or even endanger our lives.

--- p.229

Older hunter-gatherers and those who remain active throughout their lives are living proof that using muscles can help prevent muscle loss as we age.

It's not that getting older doesn't mean your muscles' ability to respond to resistance exercise ends.

In fact, if you occasionally do resistance training at a slow pace, you can reverse muscle loss regardless of age.

--- p.235

The most common area of injury when running is the knees.

I can't even count how many times I've met people (including doctors) who complained that their knees were out because they ran too much.

Does running really cause so many injuries? If we evolved to run long distances, why aren't our bodies better adapted to it?

--- p.358

I've been racking my brain for decades trying to explain why our ancestors developed so many adaptations for running such incredibly long distances.

The only plausible answer I can come up with is that it was to get my hands on meat.

--- p.350

One similarity between running and dancing that few people think about is how they transport us to another dimension.

Long, intense workouts stimulate the release of feel-good chemicals in the brain, including opioids, endorphins, and, most importantly, endocannabinoids, which are similar to the active compounds in marijuana.

That's why people who run or dance feel a heightened sense of well-being.

--- p.373

According to this theory, these diligent and helpful grandparents, who were blessed with genes that favored longevity while caring for others, had more children and grandchildren, thus passing on their genes to their descendants.

It is clear that as time goes by, humans have been selected to live longer, be more tolerant, and be useful grandparents to those around them.

--- p.383

If exercise is so damaging to the body, why is it considered good for your health? The reason is that after she stopped exercising, her body responded in a unique way, not only repairing all the damage caused by exercise, but, most importantly, even repairing some of the damage incurred when she wasn't exercising.

--- p.399

As it turns out, skipping exercise, even when you're pressed for time, can sometimes make you less productive.

Randomized controlled studies of college students confirm that much of what we already instinctively know is true.

In other words, even just briefly engaging in moderate to high intensity exercise can improve memory and concentration.

--- p.455

Ultimately, each of us is an "experiment" with different preferences based on our backgrounds, goals, and age, so there may not be an optimal combination of exercise types, just as there may not be an optimal amount of exercise.

So, although exercise may be a somewhat bizarre modern behavior, from an evolutionary perspective, we still recommend the same level of physical activity that people have been doing for centuries, albeit with different terminology.

That means working out a few hours a week, focusing on cardio and some weight training, and continuing to do so even as you get older.

--- p.486

If we simply follow that ancient, deep-rooted instinct to avoid the discomfort of physical exertion, we will not only age faster and increase our chances of dying younger, but we will also become more susceptible to numerous diseases and chronic, disabling conditions.

Along with this, you will forever miss the opportunity to live a life full of energy that comes with being strong in both body and mind.

Given our evolutionary history, a lifetime of physical activity dramatically increases our chances of living a healthy life and dying after 70 years.

--- p.549

Publisher's Review

“It is endlessly fascinating and full of surprises.

“A perfect blend of wit, scholarship, and passion.”

Bill Bryson, author of A Short History of Nearly Everything

Amazon, The New York Times

Science and Health Bestsellers

Many people resolve to exercise.

And it fails.

At first, you may be eager, but before you know it, you may find yourself lying down, fiddling with the TV remote and eating potato chips, as if drawn by a magnet.

One question arises here.

If exercise is so beneficial to health, why didn't evolutionary mechanisms select for individuals who willingly exercise? There's too much evidence from primitive tribes who lie down or sit whenever they have the chance to argue that it's a detriment to civilization.

If you think about it carefully, there are more than a few things that don't make sense when it comes to human physical activity.

We often think that as we age, we lose energy and become less active.

But how come grandparents are so diligent?

I have trouble sleeping and fall into a deep sleep under the TV light, but before I know it, I wake up at dawn and start moving around busily.

Even during the day, he is more diligent than his children and grandchildren.

Although they are unable to exert strength or power as quickly, their physical activity seems to be more active.

How can this be understood?

This book approaches the truth about exercise from the perspectives of evolutionary biology and anthropology.

Things that were previously puzzling when viewed solely through biology and physiology are now clearly explained under the light of evolution and anthropology.

The author is a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University, and his research spans paleontology, anatomy, physiology, and experimental biomechanics to present a unique science of movement.

It consists of 13 chapters in 4 parts and comprehensively covers everything from inactivity to strength, endurance, and even how to exercise well.

It presents '12 myths' about physical activities related to exercise, such as sitting, sleeping, walking, running, dancing, and lifting, and examines them one by one as if breaking down a seal.

As you read the author's witty essays, you will find yourself fidgeting and learning interesting knowledge.

“Floating based on questionable information

“It breaks down the claims about exercise.” —The New York Times

Questions this book addresses

There are many myths about exercise.

According to the authors, “The first of these myths is the idea that we humans have a natural desire to exercise.” However, a large body of evidence from anthropology and evolutionary biology consistently indicates that humans prefer to remain as still as possible.

The problem is that these myths are so pervasive that they encourage a flawed approach to exercise.

The idea that exercising is normal pushes people towards a sense of duty, trapping them in a vicious cycle that further distances them from exercising.

Rather than blindly shouting "Just do it," we need to properly understand the human body and design exercise methods that fit its evolutionary nature.

Myths give birth to other myths, and these raise all sorts of questions.

Let's hear what the author has to say.

"If exercise is truly the 'magic pill' we often hear about, where most diseases are cured or prevented by exercise, why are more people living longer than ever before, even though they're moving less? Furthermore, are humans really inherently slow and weak? Is it true that we have to sacrifice strength to gain endurance? Are chairs really killing us? Is exercise useless for weight loss? Is it normal to move less as we age? Is a glass of red wine really as good as an hour at the gym?"

The author establishes sound knowledge in a world of sports where rumors, misinformation, and groundless claims run rampant.

We formalize 12 exercise myths that we've likely heard at least once, and each chapter meticulously corrects them based on expert knowledge.

* List of '12 Superstitions'

- We evolved to exercise

- It's not natural to loaf around.

Sitting is bound to be bad for your health.

- We need to sleep 8 hours every night.

- A person with good stamina cannot also be fast.

- We evolved to become extremely strong.

- Sports is exercise

- You can't lose weight by walking.

- Running is bad for your knees.

- It's normal to move less as you get older.

- “Just do it” works

- There is an optimal level of type and amount of exercise.

“It’s full of useful tips.

“Humorous and relatable.” _The Guardian

Compositional features

This book is largely divided into four parts.

To give you a rough sketch, let's check the basic condition of our body when we are not exercising (Part 1), then look at the two major axes of exercise ability, muscle strength (Part 2) and endurance (Parts 2 and 3), and then look at appropriate exercise methods (Part 4).

In short, the first three-quarters of the book is designed to provide a scientific understanding of the human body, while the remaining second quarter provides practical guidance.

Each part is again divided into three chapters, and the content is discussed in detail. The author uses two compositional devices to make each chapter more interesting to read.

First, rather than listing dry facts or messages in each chapter, we begin with an engaging essay related to the topic and then build on that to build knowledge.

This kind of structure can easily make the writing feel sloppy if not supported by the writing skills, but the author of this book has a wit and humor that rivals that of top non-fiction writers, adding to the enjoyment of reading.

Second, rather than simply presenting exercise knowledge or tips, knowledge is conveyed by formalizing misconceptions and then dispelling them.

This so-called 'David and Goliath' narrative strategy has its own charm and pleasure, but it also has the pitfall of easily turning into a childish narrative if used carelessly.

The author maximizes the advantages of this narrative format with his uniquely detailed knowledge and his meticulousness in ensuring that the conventional wisdom does not become a mere straw man.

This book clearly explains various human physical activities, focusing on exercise, based on insights from evolutionary biology and anthropology.

At the same time, it is full of useful knowledge, such as how certain exercises are effective for various diseases, whether walking 10,000 steps is really good for your health, and how to do weight training and aerobic exercise.

Blending the author's extensive field experience, meticulous research knowledge, wit, and liveliness, this book will provide a fascinating intellectual experience and inspiration for both athletes and non-athletes.

“A perfect blend of wit, scholarship, and passion.”

Bill Bryson, author of A Short History of Nearly Everything

Amazon, The New York Times

Science and Health Bestsellers

Many people resolve to exercise.

And it fails.

At first, you may be eager, but before you know it, you may find yourself lying down, fiddling with the TV remote and eating potato chips, as if drawn by a magnet.

One question arises here.

If exercise is so beneficial to health, why didn't evolutionary mechanisms select for individuals who willingly exercise? There's too much evidence from primitive tribes who lie down or sit whenever they have the chance to argue that it's a detriment to civilization.

If you think about it carefully, there are more than a few things that don't make sense when it comes to human physical activity.

We often think that as we age, we lose energy and become less active.

But how come grandparents are so diligent?

I have trouble sleeping and fall into a deep sleep under the TV light, but before I know it, I wake up at dawn and start moving around busily.

Even during the day, he is more diligent than his children and grandchildren.

Although they are unable to exert strength or power as quickly, their physical activity seems to be more active.

How can this be understood?

This book approaches the truth about exercise from the perspectives of evolutionary biology and anthropology.

Things that were previously puzzling when viewed solely through biology and physiology are now clearly explained under the light of evolution and anthropology.

The author is a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University, and his research spans paleontology, anatomy, physiology, and experimental biomechanics to present a unique science of movement.

It consists of 13 chapters in 4 parts and comprehensively covers everything from inactivity to strength, endurance, and even how to exercise well.

It presents '12 myths' about physical activities related to exercise, such as sitting, sleeping, walking, running, dancing, and lifting, and examines them one by one as if breaking down a seal.

As you read the author's witty essays, you will find yourself fidgeting and learning interesting knowledge.

“Floating based on questionable information

“It breaks down the claims about exercise.” —The New York Times

Questions this book addresses

There are many myths about exercise.

According to the authors, “The first of these myths is the idea that we humans have a natural desire to exercise.” However, a large body of evidence from anthropology and evolutionary biology consistently indicates that humans prefer to remain as still as possible.

The problem is that these myths are so pervasive that they encourage a flawed approach to exercise.

The idea that exercising is normal pushes people towards a sense of duty, trapping them in a vicious cycle that further distances them from exercising.

Rather than blindly shouting "Just do it," we need to properly understand the human body and design exercise methods that fit its evolutionary nature.

Myths give birth to other myths, and these raise all sorts of questions.

Let's hear what the author has to say.

"If exercise is truly the 'magic pill' we often hear about, where most diseases are cured or prevented by exercise, why are more people living longer than ever before, even though they're moving less? Furthermore, are humans really inherently slow and weak? Is it true that we have to sacrifice strength to gain endurance? Are chairs really killing us? Is exercise useless for weight loss? Is it normal to move less as we age? Is a glass of red wine really as good as an hour at the gym?"

The author establishes sound knowledge in a world of sports where rumors, misinformation, and groundless claims run rampant.

We formalize 12 exercise myths that we've likely heard at least once, and each chapter meticulously corrects them based on expert knowledge.

* List of '12 Superstitions'

- We evolved to exercise

- It's not natural to loaf around.

Sitting is bound to be bad for your health.

- We need to sleep 8 hours every night.

- A person with good stamina cannot also be fast.

- We evolved to become extremely strong.

- Sports is exercise

- You can't lose weight by walking.

- Running is bad for your knees.

- It's normal to move less as you get older.

- “Just do it” works

- There is an optimal level of type and amount of exercise.

“It’s full of useful tips.

“Humorous and relatable.” _The Guardian

Compositional features

This book is largely divided into four parts.

To give you a rough sketch, let's check the basic condition of our body when we are not exercising (Part 1), then look at the two major axes of exercise ability, muscle strength (Part 2) and endurance (Parts 2 and 3), and then look at appropriate exercise methods (Part 4).

In short, the first three-quarters of the book is designed to provide a scientific understanding of the human body, while the remaining second quarter provides practical guidance.

Each part is again divided into three chapters, and the content is discussed in detail. The author uses two compositional devices to make each chapter more interesting to read.

First, rather than listing dry facts or messages in each chapter, we begin with an engaging essay related to the topic and then build on that to build knowledge.

This kind of structure can easily make the writing feel sloppy if not supported by the writing skills, but the author of this book has a wit and humor that rivals that of top non-fiction writers, adding to the enjoyment of reading.

Second, rather than simply presenting exercise knowledge or tips, knowledge is conveyed by formalizing misconceptions and then dispelling them.

This so-called 'David and Goliath' narrative strategy has its own charm and pleasure, but it also has the pitfall of easily turning into a childish narrative if used carelessly.

The author maximizes the advantages of this narrative format with his uniquely detailed knowledge and his meticulousness in ensuring that the conventional wisdom does not become a mere straw man.

This book clearly explains various human physical activities, focusing on exercise, based on insights from evolutionary biology and anthropology.

At the same time, it is full of useful knowledge, such as how certain exercises are effective for various diseases, whether walking 10,000 steps is really good for your health, and how to do weight training and aerobic exercise.

Blending the author's extensive field experience, meticulous research knowledge, wit, and liveliness, this book will provide a fascinating intellectual experience and inspiration for both athletes and non-athletes.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 10, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 644 pages | 922g | 152*225*32mm

- ISBN13: 9791189336752

- ISBN10: 1189336758

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)