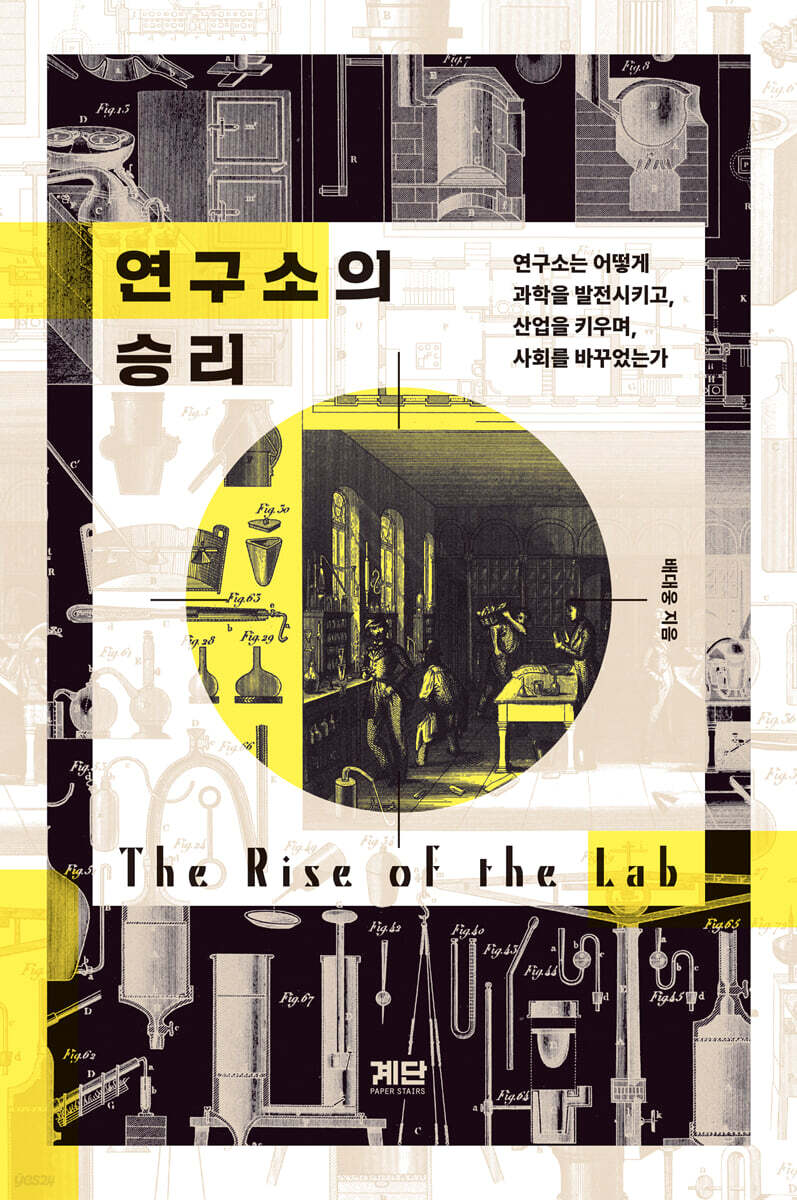

The Institute's Victory

|

Description

Book Introduction

Research institutes are "social inventions" that advance science.

In it, individual passion becomes an institution,

Knowledge becomes industry, and innovation becomes history.

Scientific progress begins with the talent of a single individual, but sustaining that progress requires organization, leadership, finances, and institutions.

As science transcended the limitations of the individual, research institutes emerged as key institutions of a new era.

But a research institute is not just a collection of laboratories.

It involves intertwining the ideals of scientists, political judgments, industrial interests, local needs, and citizens' taxes.

In the debate surrounding where to establish research institutes and what to research, science expands beyond the pursuit of knowledge to include social choices and national vision.

"The Triumph of the Research Institute" traces how the world's research institutes have shaped the advancement of science and the fate of nations over the past century.

The story, which began at the Imperial Institute of Physics and Technology in Germany in 1887, continues with the Max Planck Society, the Physical and Chemical Research Institute, Lawrence Berkeley, NASA, and KIST, demonstrating the power of research institutes to systematize science, grow industry, and transform society.

Bringing science back into society, this book asks:

For whom do research institutes exist? And what kind of research institute and what kind of future will we choose?

In it, individual passion becomes an institution,

Knowledge becomes industry, and innovation becomes history.

Scientific progress begins with the talent of a single individual, but sustaining that progress requires organization, leadership, finances, and institutions.

As science transcended the limitations of the individual, research institutes emerged as key institutions of a new era.

But a research institute is not just a collection of laboratories.

It involves intertwining the ideals of scientists, political judgments, industrial interests, local needs, and citizens' taxes.

In the debate surrounding where to establish research institutes and what to research, science expands beyond the pursuit of knowledge to include social choices and national vision.

"The Triumph of the Research Institute" traces how the world's research institutes have shaped the advancement of science and the fate of nations over the past century.

The story, which began at the Imperial Institute of Physics and Technology in Germany in 1887, continues with the Max Planck Society, the Physical and Chemical Research Institute, Lawrence Berkeley, NASA, and KIST, demonstrating the power of research institutes to systematize science, grow industry, and transform society.

Bringing science back into society, this book asks:

For whom do research institutes exist? And what kind of research institute and what kind of future will we choose?

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

Entering

Part 1: The Nationalization of Science: The Birth of Research Institutes and the Establishment of a Modern Scientific System

1.

The emergence of national research institutes: the Imperial Institute of Physics and Technology in Germany in 1887

2.

Declaration of Independence for Basic Research: The Kaiser Wilhelm Society of Germany, 1911

3.

Science in War: The Kaiser Wilhelm Society in Germany, 1915

4.

The Age of Big Science: Berkeley Radiation Laboratory, 1931

5.

Scattered Scientists: The Kaiser Wilhelm Society in Germany, 1933

6.

Nuclear Fission Chain Reaction: Kaiser Wilhelm Society, Germany, 1938

7.

Destroyer of Worlds: Los Alamos National Laboratory, 1945

8.

A Rocket Launched by Politicians: NASA, 1958

9.

The Unintended Consequences of Technology: The Advanced Research Projects Agency, 1969

Part 2: The Power of Technology's Leap Forward - The Technology of Pursuit and the Resurgence of a Scientific Powerhouse

10.

The East Chasing the West: The Japanese Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, 1917

11.

Self-Reliance in Science: The Physical and Chemical Research Institute of Japan, 1921

12.

A Land of New Opportunity: The Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, 1933

13.

Science Revived in a Defeated Nation: The Max Planck Society in Germany, 1948

14.

78 Years of Accumulation: 1949, Physical and Chemical Research Institute, Japan

15.

Energy from the Head: Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, 1959

16.

Technology to Feed the Nation: Korea Institute of Science and Technology, 1966

17.

400 Trillion Experiments: 2016, RIKEN, Japan

Part 3: Earth Becomes a Laboratory - Cross-Border Collaboration and Connected World Science

18.

Quantum Jump: 1922 Danish Institute for Theoretical Physics

19.

The Value of a Large Research Facility: Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, USA, 1974

20.

The Effects of Uncertain Investments: National Science Foundation, 1975

21.

Science that Integrates Society: Max Planck Society, Germany, 1990

22.

A Reversal in European Physics: CERN, 2012

23.

Two Women and the Gene Scissors: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, USA, and Max Planck Society, Germany, 2020

24.

Operation Warp Speed: A Vaccine Created by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 2022

25.

Formation of the Earth Defense Force: NASA, 2022

Books and articles referenced

Acknowledgements

Search

Entering

Part 1: The Nationalization of Science: The Birth of Research Institutes and the Establishment of a Modern Scientific System

1.

The emergence of national research institutes: the Imperial Institute of Physics and Technology in Germany in 1887

2.

Declaration of Independence for Basic Research: The Kaiser Wilhelm Society of Germany, 1911

3.

Science in War: The Kaiser Wilhelm Society in Germany, 1915

4.

The Age of Big Science: Berkeley Radiation Laboratory, 1931

5.

Scattered Scientists: The Kaiser Wilhelm Society in Germany, 1933

6.

Nuclear Fission Chain Reaction: Kaiser Wilhelm Society, Germany, 1938

7.

Destroyer of Worlds: Los Alamos National Laboratory, 1945

8.

A Rocket Launched by Politicians: NASA, 1958

9.

The Unintended Consequences of Technology: The Advanced Research Projects Agency, 1969

Part 2: The Power of Technology's Leap Forward - The Technology of Pursuit and the Resurgence of a Scientific Powerhouse

10.

The East Chasing the West: The Japanese Institute of Physical and Chemical Research, 1917

11.

Self-Reliance in Science: The Physical and Chemical Research Institute of Japan, 1921

12.

A Land of New Opportunity: The Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, 1933

13.

Science Revived in a Defeated Nation: The Max Planck Society in Germany, 1948

14.

78 Years of Accumulation: 1949, Physical and Chemical Research Institute, Japan

15.

Energy from the Head: Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, 1959

16.

Technology to Feed the Nation: Korea Institute of Science and Technology, 1966

17.

400 Trillion Experiments: 2016, RIKEN, Japan

Part 3: Earth Becomes a Laboratory - Cross-Border Collaboration and Connected World Science

18.

Quantum Jump: 1922 Danish Institute for Theoretical Physics

19.

The Value of a Large Research Facility: Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, USA, 1974

20.

The Effects of Uncertain Investments: National Science Foundation, 1975

21.

Science that Integrates Society: Max Planck Society, Germany, 1990

22.

A Reversal in European Physics: CERN, 2012

23.

Two Women and the Gene Scissors: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, USA, and Max Planck Society, Germany, 2020

24.

Operation Warp Speed: A Vaccine Created by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, 2022

25.

Formation of the Earth Defense Force: NASA, 2022

Books and articles referenced

Acknowledgements

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

There is an underlying perception that research labs are unfamiliar, difficult, and opaque spaces.

This is despite the fact that the majority of the public agrees on the importance of science and technology.

Our country has one of the highest ratios of GDP invested in science and technology in the world. However, the paradox is that the citizens who pay taxes for this work are unaware of what the research institutes actually do.

This is not just because of people's indifference.

The problem lies rather within the research institute.

This is because the institute did not explain itself well enough and did not create a language to explain it.

--- p.10

The question of what a research institute should look like is directly related to the question of what kind of society we are aiming for.

Physicist Richard Feynman said, “Today’s problems cannot be solved with yesterday’s solutions.”

Our country is currently facing unprecedented challenges, including a population cliff, low growth, international technological competition, climate change, and emerging infectious diseases.

It is the research institute that can create the 'solution of the day' to solve this.

This is possible by transforming the tasks of society into the logic of science and translating the achievements of science into the language of society.

So the research institute must re-enter society.

We must explain science, imagine the future, and build trust with citizens.

--- p.15

After these complex considerations, Carl Bosch was appointed the third chairman in 1937.

Bosch was a chemist who, together with Fritz Haber, developed the Haber-Bosch method and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1931.

At the same time, he was also the head of the giant chemical company IG Farben.

In other words, he was a scientist and an entrepreneur, with a contrasting identity to Planck, who was a theoretical physicist and professor.

Even after taking office as chairman, Bosch did not resign from his position as head of Igefarben; rather, he brought his employees into the association's advisory board.

And he lived in Heidelberg, close to the company, rather than in Berlin, where the association's headquarters were located.

He prioritized company management over the Kaiser Wilhelm Association.

This also meant a change in the association's operational principles.

In other words, while the era of Adolf Harnack and Max Planck emphasized the autonomy of science and pure research, now the emphasis is on purposeful research and application/development for companies.

(……) The connection between the Nazis and the Kaiser Wilhelm Association became stronger through the corporation.

This also had a major impact on the direction and nature of scientific research.

The Kaiser Wilhelm Association was tasked with not only developing weapons, but also undertaking projects that would provide scientific justification for Nazi ideology.

--- p.88~89

During his tenure as president (1961–1972), Butenandt responded to the progressive tendencies brought about by the '68 Movement.

In the wake of the student movement, interest in autonomy and participation in research fields has grown, and young scientists have also demanded expanded voices.

In 1972, the association headquarters partially accepted these demands through revision of the articles of association.

As a result, the authority of the research institute director was decentralized, and the organization was democratized through the creation of an internal opinion coordination body.

And the Friedrich Miescher Institute, founded in Tübingen in 1969, provided experimental space for young scientists.

The young scientist training program, which is the pride of the Max Planck Society today, began to become widespread from this time.

Thanks to this, young people who have just completed their doctoral studies can conduct independent research.

The principle of researcher autonomy established by Harnack at the time of its establishment has gained a more solid foundation.

--- p.187

This is because an unimaginably large amount of electricity was needed to run the giant steel mill furnaces and operate the factory day and night.

However, until the early 1970s, the nation's power generation facilities were unable to meet the rapidly increasing demand.

If things continued this way, it was clear that steel mills and factories would shut down due to a lack of electricity, and economic development plans would face serious setbacks.

At this time, the alternative of nuclear power introduced by the Syngman Rhee government began to produce results.

In the mid-1960s, the Atomic Energy Research Institute began construction of a nuclear power plant, and Unit 1 of the Gori Nuclear Power Plant was completed in April 1978.

It was the 21st such achievement worldwide.

As Sisler predicted, it took about 20 years for the country to go from candlelight to nuclear power.

Of course, the reactor and major components of Gori Unit 1 were imported from Westinghouse in the United States.

However, most of the staff running it are Korean.

--- p.213

These characteristics are also revealed in KIST's benchmarking model.

The model for KIST originally proposed by the United States was Bell Labs.

Bell Labs, founded by the telephone and telegraph company AT&T, was known for its liberal academic culture.

(……) However, Choi Hyeong-seop thought that this system was not suitable for KIST.

So the model that was counter-proposed was the Battelle Memorial Institute.

The most notable characteristic of this research center is that it operates on commissioned research projects from industry and the government. This has led to the birth of innovative industrial technologies such as CDs, copier toner, and fuel cells.

Following this example, KIST also aimed to become the ‘Korean version of Batel.’

--- p.218~219

KIST's research method has become established as a national development paradigm.

In academic terms, it is called catch-up research and development or fast follower.

It is a strategy to quickly catch up by imitating the technology of advanced countries.

This paradigm has been very successful.

As KIST, which started as a general research institute, steadily grew, several research institutes spun off and specialized in each technology field in the 1970s and 1980s.

This is the origin of today's government-funded research institute and Daedeok Special Zone.

Thanks to the science and technology-based export-led strategy they led, Korea joined the ranks of advanced countries more quickly than any other country in the world.

These changes are significant not only in economic and industrial terms.

It was also the first major event in Korean history where scientists and engineers changed the fate of the nation.

This is despite the fact that the majority of the public agrees on the importance of science and technology.

Our country has one of the highest ratios of GDP invested in science and technology in the world. However, the paradox is that the citizens who pay taxes for this work are unaware of what the research institutes actually do.

This is not just because of people's indifference.

The problem lies rather within the research institute.

This is because the institute did not explain itself well enough and did not create a language to explain it.

--- p.10

The question of what a research institute should look like is directly related to the question of what kind of society we are aiming for.

Physicist Richard Feynman said, “Today’s problems cannot be solved with yesterday’s solutions.”

Our country is currently facing unprecedented challenges, including a population cliff, low growth, international technological competition, climate change, and emerging infectious diseases.

It is the research institute that can create the 'solution of the day' to solve this.

This is possible by transforming the tasks of society into the logic of science and translating the achievements of science into the language of society.

So the research institute must re-enter society.

We must explain science, imagine the future, and build trust with citizens.

--- p.15

After these complex considerations, Carl Bosch was appointed the third chairman in 1937.

Bosch was a chemist who, together with Fritz Haber, developed the Haber-Bosch method and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1931.

At the same time, he was also the head of the giant chemical company IG Farben.

In other words, he was a scientist and an entrepreneur, with a contrasting identity to Planck, who was a theoretical physicist and professor.

Even after taking office as chairman, Bosch did not resign from his position as head of Igefarben; rather, he brought his employees into the association's advisory board.

And he lived in Heidelberg, close to the company, rather than in Berlin, where the association's headquarters were located.

He prioritized company management over the Kaiser Wilhelm Association.

This also meant a change in the association's operational principles.

In other words, while the era of Adolf Harnack and Max Planck emphasized the autonomy of science and pure research, now the emphasis is on purposeful research and application/development for companies.

(……) The connection between the Nazis and the Kaiser Wilhelm Association became stronger through the corporation.

This also had a major impact on the direction and nature of scientific research.

The Kaiser Wilhelm Association was tasked with not only developing weapons, but also undertaking projects that would provide scientific justification for Nazi ideology.

--- p.88~89

During his tenure as president (1961–1972), Butenandt responded to the progressive tendencies brought about by the '68 Movement.

In the wake of the student movement, interest in autonomy and participation in research fields has grown, and young scientists have also demanded expanded voices.

In 1972, the association headquarters partially accepted these demands through revision of the articles of association.

As a result, the authority of the research institute director was decentralized, and the organization was democratized through the creation of an internal opinion coordination body.

And the Friedrich Miescher Institute, founded in Tübingen in 1969, provided experimental space for young scientists.

The young scientist training program, which is the pride of the Max Planck Society today, began to become widespread from this time.

Thanks to this, young people who have just completed their doctoral studies can conduct independent research.

The principle of researcher autonomy established by Harnack at the time of its establishment has gained a more solid foundation.

--- p.187

This is because an unimaginably large amount of electricity was needed to run the giant steel mill furnaces and operate the factory day and night.

However, until the early 1970s, the nation's power generation facilities were unable to meet the rapidly increasing demand.

If things continued this way, it was clear that steel mills and factories would shut down due to a lack of electricity, and economic development plans would face serious setbacks.

At this time, the alternative of nuclear power introduced by the Syngman Rhee government began to produce results.

In the mid-1960s, the Atomic Energy Research Institute began construction of a nuclear power plant, and Unit 1 of the Gori Nuclear Power Plant was completed in April 1978.

It was the 21st such achievement worldwide.

As Sisler predicted, it took about 20 years for the country to go from candlelight to nuclear power.

Of course, the reactor and major components of Gori Unit 1 were imported from Westinghouse in the United States.

However, most of the staff running it are Korean.

--- p.213

These characteristics are also revealed in KIST's benchmarking model.

The model for KIST originally proposed by the United States was Bell Labs.

Bell Labs, founded by the telephone and telegraph company AT&T, was known for its liberal academic culture.

(……) However, Choi Hyeong-seop thought that this system was not suitable for KIST.

So the model that was counter-proposed was the Battelle Memorial Institute.

The most notable characteristic of this research center is that it operates on commissioned research projects from industry and the government. This has led to the birth of innovative industrial technologies such as CDs, copier toner, and fuel cells.

Following this example, KIST also aimed to become the ‘Korean version of Batel.’

--- p.218~219

KIST's research method has become established as a national development paradigm.

In academic terms, it is called catch-up research and development or fast follower.

It is a strategy to quickly catch up by imitating the technology of advanced countries.

This paradigm has been very successful.

As KIST, which started as a general research institute, steadily grew, several research institutes spun off and specialized in each technology field in the 1970s and 1980s.

This is the origin of today's government-funded research institute and Daedeok Special Zone.

Thanks to the science and technology-based export-led strategy they led, Korea joined the ranks of advanced countries more quickly than any other country in the world.

These changes are significant not only in economic and industrial terms.

It was also the first major event in Korean history where scientists and engineers changed the fate of the nation.

--- p.227~228

Publisher's Review

“Every moment science changes the world,

“At the center of it all has always been the research lab.”

Unveiling the blueprint for a research institute that has driven science, industry, and national strategy.

Everything in the world is accomplished by people,

Nothing lasts without organization.

_ Jean Monet

The birth of a "social device" called the research institute

Institutional inventions that emerged to diagnose the nation's weaknesses and plan for the future

A research institute is not an extension of a scientist's laboratory.

It was a 'social device' that emerged in similar forms when the nation faced its own weaknesses - when industry needed standards, when imitation reached its limits, when the foundations needed to be rebuilt.

In the late 19th century, Germany created the Imperial Institute of Physics and Technology when the lack of precision measurement and technical standards became a weakness in its industrial competitiveness.

The basic science system that later became the Max Planck Society was an institutional experiment that elevated science to a long-term national strategic function.

In the 1910s, Japan achieved industrialization but was unable to escape imitation of the West. In this period, Jokichi Takamine proposed the National Science Research Institute, attempting to redraw the path of development that had been stalled.

This problem awareness brought together the academic, business, and political circles, and was ultimately realized in the form of the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research.

At the end of its pursuit strategy, Japan attempted to use basic science as a breakthrough to 'stand on its own.'

In Korea, the conditions were different.

The power outage immediately after liberation, dependence on foreign technology and raw materials, and the instability of energy supply due to the Cold War and the oil shock soon became a matter of national survival.

By quickly establishing laws and organizations and introducing foreign knowledge and systems, the institute became one of the key infrastructures supporting Korea's industrial base, power security, and national reconstruction.

The establishment of the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute in 1959 was the result of this condensation and became the starting point of the national R&D system.

The paths taken by Germany's Max Planck Society, Japan's RIKEN, and the U.S. national research institute system over time ultimately lead to the same question.

“When did the country create a research institute, and why did it stake its future on that institution?”

In other words, how was the research institute invented at the intersection of crisis and necessity? And how did that choice shape science, industry, and national strategy?

In this way, the origins of a research institute always begin from a broader background than science itself.

The birth of a research institute has always been accompanied by the question of "what to research" and "who will lead it."

And the nation designed its future right there on the spot.

The fact that today's Korea faces the same question is one of the recurring scenes this book shows.

- Asking about the new leap forward for Korean research institutes through field experience interpreting overseas models.

The first narrative of the institute's birth, growth, and strategy, told by someone who has seen it from the inside.

Understanding a lab goes beyond just looking at a list of lab equipment or research results.

We must understand the complex mechanisms that intertwine education, industry, political choices, the flow of talent, and even the national vision.

"The Triumph of the Laboratory" shows in detail how this device came to be and why it has become even more important today, within the context of global history and technological competition.

The author is a practitioner who has been in charge of research institute planning and overseas system transplantation for over 15 years at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Evaluation and Planning (KISTEP), Korea Basic Science Institute (KBSi), and Institute for Basic Science (IBS).

The experience of observing the logic, budget, politics, and movement of talent at research institutes from a close perspective has become the driving force that weaves together the history of research institutes around the world into a single flow.

Based on a sociological perspective, the author views science, policy, institutions, and society as a single system, weaving together a three-dimensional history of research institutes around the world.

The birth and transformation of the Max Planck Society, the RIKEN, and the U.S. National Laboratories, and the demands of the times that followed, are connected as one great current.

He sees the institute not as a simple institution, but as a "problem-solving power for the nation."

This perspective makes it clear why understanding research institutes is a strategic asset in Korea today.

The author's great strength is his smooth and clear writing style without missing any of the details of the scene.

Thanks to the balanced sentences that come from consistent writing practice, readers can follow the changes over the past century—from the birth of the modern national research institute to today's central focus on international cooperation—naturally and engagingly.

For general readers curious about what a research institute is, this book will be the most clear introduction, and for readers contemplating science and technology policy, it will provide a perspective from which to envision future strategies.

- The politics of interest surrounding the research institute

The structure revealed in the Max Planck model of unified Germany, and the scenes repeated in Korea today.

In research laboratories, scientific ideals and political realities are always intertwined.

This book deals with the Max Planck Society during the period of German reunification as the case that most clearly reveals the mechanisms of such conflict and coordination.

In 1990, the task of bringing together West Germany's world-class research system and the East German system with weak research capabilities was not a simple integration.

The Max Planck Society adopted the West German model as the national standard, based on the criteria of "freedom of research" and "organizational autonomy."

To this end, research groups were first established in East German universities to restore their research functions, and then 18 research institutes were established in East Germany throughout the 1990s.

The problem was cost.

Government support was woefully inadequate, and the association even resorted to restructuring existing research institutes and reducing positions to secure its own budget.

Chairman Hubert Markl, who was brought in from outside, reorganized the entire organization with a strong reform drive, even risking internal opposition.

This process ultimately turned the research system upside down to the point where it was evaluated as the re-establishment of the Max Planck Society.

And the achievements made on top of that tension expanded beyond science to social integration.

East German cities such as Dresden, Leipzig, and Potsdam have become new innovation hubs for unified Germany, with the economy, industry, and universities revitalized around research institutes.

The institute has proven to be both a foundation for science and a key infrastructure for balanced regional development.

But this structure is not unique to Germany.

This scene is not unfamiliar in today's Korea.

South Jeolla Province and Gwangju, which have significant renewable energy development potential, are actively competing to establish AI innovation research centers and energy hubs.

Naju is pursuing the agenda of attracting an energy research institute and a nuclear fusion demonstration reactor with Kentech as its backdrop.

Jeollanam-do and Jeollabuk-do are also looking to the "national research institute" as a strategic resource to reverse their economically backward conditions compared to the Gyeongsang region.

Daejeon, as a traditional research complex, is promoting the attraction of new research institutions linked to its existing ecosystem, while the Gori, Wolseong, and Gyeongju areas are demanding related research institutes as political compensation for the nuclear waste issue.

The metropolitan area is also seeking to maintain its competitiveness by expanding its research infrastructure, and Gangwon Province, driven by the logic of regional politics that "since we have nothing, we must accept one," is using attracting research institutes as a starting point for development.

In this way, each region in Korea interprets the attraction of research institutes based on its own industrial resources, political interests, and regional identity.

As the logic of renewable energy in Jeollanam-do, nuclear power in Gyeongbuk, research infrastructure in Pohang, research complexes in Daejeon, premium metropolitan area in Seoul, and "empty land" in Gangwon collide with each other, research institutes become political choices and means of balanced national development before they are scientific institutions.

The pressures of German reunification—financial constraints, regional demands, national strategy, and organizational autonomy—are echoed in Korea today in the competition to host research institutes.

When local resources and political interests change the meaning of a research institute, it can go beyond being a scientific institution and become a "blueprint for the region's future."

Research institutes always operate under structural tension.

There's no avoiding that tension.

But if nations make wise choices about where and how to deploy science, this tension can be transformed into a future engine of growth.

- The foundation of industry and innovation created by the research institute

How KIST's "Research-Based Industrialization" Works

The direction of Korea's industrialization was redrawn with the establishment of KIST in 1966.

At that time, Korea was a poor agricultural country that depended on small-scale light industry and exports of some raw materials.

It was a time when human resources, technology, and capital were all in short supply, and wigs and textiles ranked first and second in exports.

Under these conditions, the very idea of creating “technology that will feed the country” was a new paradigm.

KIST has clearly declared its goal of being a research institute for industrialization.

The structure was to import overseas source technology, modify it to suit the production environment of domestic companies, and then directly apply it to industry.

This was also the reason why the Battelle Memorial Laboratory chose to conduct contract research under government and corporate projects instead of Bell Labs' "free basic research."

Research topics were selected based on industrial demand, and fields that constituted the basic strength of industry at the time, such as metals, chemicals, electronics, machinery, and food, became the core.

What was decisive was talent and autonomy.

Korean scientists who had been working in the United States and Europe returned in large numbers, and the government provided KIST with research autonomy and bold financial support.

The operating system, free from audits or government approvals, and the salary and research environment, which were exceptional for the time, created a new research ecosystem that did not exist in Korea.

This system became the basic grammar of Korean science and technology policy for the following decades.

The results quickly translated into industrial achievements. KIST spearheaded the domestic production of technologies that were previously dependent on imports, such as magnetic tape, freon gas, and copper-clad steel wire, and numerous companies grew based on these technologies.

Looking at the bigger picture, KIST was involved in the initial design of the POSCO, shipbuilding, electronics, and automobile industries.

The steel mill construction plan, in which these metallurgists participated, became the starting point for POSCO, and as the steel-related industries took hold, the foundation for the heavy chemical industry was also established.

A circular structure has been formed in which research institutes create industries, and industries in turn expand research institutes.

This catch-up R&D model played a decisive role in tying Korea's industrialization strategy into a single system.

This allows the cycle of acquiring, applying, and improving technology to be repeated in short cycles at the national level.

The subsequent emergence of government-funded research institutes and Daedeok Special Zones can also be said to be an extension of this structure.

What KIST demonstrated was not simply technological development, but the fact that a nation can redefine the framework of an industrial nation through research institutes.

If Germany reorganized its regions into research institutes, Korea designed the foundation of its national strategy with research institutes.

The rise of the "global institution" called the research institute

The era of international cooperation supporting super-scale science

Today's research institutes are no longer national laboratories.

It is a massive operational mechanism that addresses global risks and challenges.

The unusually rapid development of a vaccine immediately following the pandemic was possible because research institutes and companies in the US, Europe, and Asia shared data, cross-validated technologies, and internationally divided clinical trials and production.

The same goes for space exploration and asteroid impact preparedness.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) are working together to manage space risks that cannot be addressed by a single country by integrating their observation capabilities and probes into separate systems.

Even ultra-large instruments like particle accelerators and gravitational wave observatories already require the combined funding, technology, and human resources of dozens of countries to maintain. CERN's Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is a prime example.

This trend is even more evident in climate change research.

Satellite observations, ocean and atmosphere monitoring, and long-term modeling only become meaningful when data from research institutes around the world are integrated into a network.

Beyond being a knowledge-producing institution, the institute has become an operational platform for addressing global issues.

What this change tells us is clear.

The point is that research institutes are no longer just national laboratories, but are now core platforms for global strategy.

International scientific cooperation is not just a matter of equipment and money.

Rather, it is the 'network of people' that is created through the interweaving of organization, culture, leadership, and movement of experts that is the essence.

It is at this point that the nature of the research institute begins to change significantly.

- Why we need to talk about the lab again today

Beyond investment uncertainty and political controversy, the future is first revealed in the lab.

The research lab has always been a difficult choice.

It costs a lot of money, the results are uncertain, and political controversy is inevitable.

Just as the National Science Foundation (NSF) was ridiculed in the 1970s for its basic research on topics like "Why do people fall in love?", research institutes are still constantly plagued by the question, "What's the use right now?"

But as time goes by, the context changes.

Studies that were once considered ridiculous have become core knowledge in psychology and brain science, and NSFNET, which was established by the NSF as a dedicated network for researchers, has led to today's Internet.

Slow investments made at points where utility was not visible eventually became the foundation of civilization.

This problem is acute in Korea as well.

The attraction of research institutes is always at the center of conflict due to inter-regional competition, political interests, and industrial advantages and disadvantages.

It's natural to wonder, "What can I really get out of this investment?"

But history shows a different truth.

Once properly established, a research institute becomes the root of technology, the source of industry, and the starting point of future infrastructure.

The knowledge created by the research institute will change the future 10 years from now, and the infrastructure built by the research institute will create the industry 30 years from now.

The choices that are causing controversy now will ultimately determine the pace of innovation in a country.

《Triumph of the Laboratory》 addresses that very scene head-on.

This study traces the origins of the research institute, why it always operates amid opposition and suspicion, and why, despite this, the future always begins in the research institute, going back and forth between world history and the reality of Korea.

This book does not glorify the institute or repeat the heroic narrative.

Instead, it shows the courage of a nation that made an uncertain investment, the competition between regions for the future, and the real-life clash between politics and science.

The reason we need to talk about the lab again today is clear.

The future is not determined by science and technology alone.

When industrial environments, institutional choices, and political imagination are combined, a completely different path opens up.

And the place where that choice first appears is the research lab.

“At the center of it all has always been the research lab.”

Unveiling the blueprint for a research institute that has driven science, industry, and national strategy.

Everything in the world is accomplished by people,

Nothing lasts without organization.

_ Jean Monet

The birth of a "social device" called the research institute

Institutional inventions that emerged to diagnose the nation's weaknesses and plan for the future

A research institute is not an extension of a scientist's laboratory.

It was a 'social device' that emerged in similar forms when the nation faced its own weaknesses - when industry needed standards, when imitation reached its limits, when the foundations needed to be rebuilt.

In the late 19th century, Germany created the Imperial Institute of Physics and Technology when the lack of precision measurement and technical standards became a weakness in its industrial competitiveness.

The basic science system that later became the Max Planck Society was an institutional experiment that elevated science to a long-term national strategic function.

In the 1910s, Japan achieved industrialization but was unable to escape imitation of the West. In this period, Jokichi Takamine proposed the National Science Research Institute, attempting to redraw the path of development that had been stalled.

This problem awareness brought together the academic, business, and political circles, and was ultimately realized in the form of the Institute of Physical and Chemical Research.

At the end of its pursuit strategy, Japan attempted to use basic science as a breakthrough to 'stand on its own.'

In Korea, the conditions were different.

The power outage immediately after liberation, dependence on foreign technology and raw materials, and the instability of energy supply due to the Cold War and the oil shock soon became a matter of national survival.

By quickly establishing laws and organizations and introducing foreign knowledge and systems, the institute became one of the key infrastructures supporting Korea's industrial base, power security, and national reconstruction.

The establishment of the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute in 1959 was the result of this condensation and became the starting point of the national R&D system.

The paths taken by Germany's Max Planck Society, Japan's RIKEN, and the U.S. national research institute system over time ultimately lead to the same question.

“When did the country create a research institute, and why did it stake its future on that institution?”

In other words, how was the research institute invented at the intersection of crisis and necessity? And how did that choice shape science, industry, and national strategy?

In this way, the origins of a research institute always begin from a broader background than science itself.

The birth of a research institute has always been accompanied by the question of "what to research" and "who will lead it."

And the nation designed its future right there on the spot.

The fact that today's Korea faces the same question is one of the recurring scenes this book shows.

- Asking about the new leap forward for Korean research institutes through field experience interpreting overseas models.

The first narrative of the institute's birth, growth, and strategy, told by someone who has seen it from the inside.

Understanding a lab goes beyond just looking at a list of lab equipment or research results.

We must understand the complex mechanisms that intertwine education, industry, political choices, the flow of talent, and even the national vision.

"The Triumph of the Laboratory" shows in detail how this device came to be and why it has become even more important today, within the context of global history and technological competition.

The author is a practitioner who has been in charge of research institute planning and overseas system transplantation for over 15 years at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Evaluation and Planning (KISTEP), Korea Basic Science Institute (KBSi), and Institute for Basic Science (IBS).

The experience of observing the logic, budget, politics, and movement of talent at research institutes from a close perspective has become the driving force that weaves together the history of research institutes around the world into a single flow.

Based on a sociological perspective, the author views science, policy, institutions, and society as a single system, weaving together a three-dimensional history of research institutes around the world.

The birth and transformation of the Max Planck Society, the RIKEN, and the U.S. National Laboratories, and the demands of the times that followed, are connected as one great current.

He sees the institute not as a simple institution, but as a "problem-solving power for the nation."

This perspective makes it clear why understanding research institutes is a strategic asset in Korea today.

The author's great strength is his smooth and clear writing style without missing any of the details of the scene.

Thanks to the balanced sentences that come from consistent writing practice, readers can follow the changes over the past century—from the birth of the modern national research institute to today's central focus on international cooperation—naturally and engagingly.

For general readers curious about what a research institute is, this book will be the most clear introduction, and for readers contemplating science and technology policy, it will provide a perspective from which to envision future strategies.

- The politics of interest surrounding the research institute

The structure revealed in the Max Planck model of unified Germany, and the scenes repeated in Korea today.

In research laboratories, scientific ideals and political realities are always intertwined.

This book deals with the Max Planck Society during the period of German reunification as the case that most clearly reveals the mechanisms of such conflict and coordination.

In 1990, the task of bringing together West Germany's world-class research system and the East German system with weak research capabilities was not a simple integration.

The Max Planck Society adopted the West German model as the national standard, based on the criteria of "freedom of research" and "organizational autonomy."

To this end, research groups were first established in East German universities to restore their research functions, and then 18 research institutes were established in East Germany throughout the 1990s.

The problem was cost.

Government support was woefully inadequate, and the association even resorted to restructuring existing research institutes and reducing positions to secure its own budget.

Chairman Hubert Markl, who was brought in from outside, reorganized the entire organization with a strong reform drive, even risking internal opposition.

This process ultimately turned the research system upside down to the point where it was evaluated as the re-establishment of the Max Planck Society.

And the achievements made on top of that tension expanded beyond science to social integration.

East German cities such as Dresden, Leipzig, and Potsdam have become new innovation hubs for unified Germany, with the economy, industry, and universities revitalized around research institutes.

The institute has proven to be both a foundation for science and a key infrastructure for balanced regional development.

But this structure is not unique to Germany.

This scene is not unfamiliar in today's Korea.

South Jeolla Province and Gwangju, which have significant renewable energy development potential, are actively competing to establish AI innovation research centers and energy hubs.

Naju is pursuing the agenda of attracting an energy research institute and a nuclear fusion demonstration reactor with Kentech as its backdrop.

Jeollanam-do and Jeollabuk-do are also looking to the "national research institute" as a strategic resource to reverse their economically backward conditions compared to the Gyeongsang region.

Daejeon, as a traditional research complex, is promoting the attraction of new research institutions linked to its existing ecosystem, while the Gori, Wolseong, and Gyeongju areas are demanding related research institutes as political compensation for the nuclear waste issue.

The metropolitan area is also seeking to maintain its competitiveness by expanding its research infrastructure, and Gangwon Province, driven by the logic of regional politics that "since we have nothing, we must accept one," is using attracting research institutes as a starting point for development.

In this way, each region in Korea interprets the attraction of research institutes based on its own industrial resources, political interests, and regional identity.

As the logic of renewable energy in Jeollanam-do, nuclear power in Gyeongbuk, research infrastructure in Pohang, research complexes in Daejeon, premium metropolitan area in Seoul, and "empty land" in Gangwon collide with each other, research institutes become political choices and means of balanced national development before they are scientific institutions.

The pressures of German reunification—financial constraints, regional demands, national strategy, and organizational autonomy—are echoed in Korea today in the competition to host research institutes.

When local resources and political interests change the meaning of a research institute, it can go beyond being a scientific institution and become a "blueprint for the region's future."

Research institutes always operate under structural tension.

There's no avoiding that tension.

But if nations make wise choices about where and how to deploy science, this tension can be transformed into a future engine of growth.

- The foundation of industry and innovation created by the research institute

How KIST's "Research-Based Industrialization" Works

The direction of Korea's industrialization was redrawn with the establishment of KIST in 1966.

At that time, Korea was a poor agricultural country that depended on small-scale light industry and exports of some raw materials.

It was a time when human resources, technology, and capital were all in short supply, and wigs and textiles ranked first and second in exports.

Under these conditions, the very idea of creating “technology that will feed the country” was a new paradigm.

KIST has clearly declared its goal of being a research institute for industrialization.

The structure was to import overseas source technology, modify it to suit the production environment of domestic companies, and then directly apply it to industry.

This was also the reason why the Battelle Memorial Laboratory chose to conduct contract research under government and corporate projects instead of Bell Labs' "free basic research."

Research topics were selected based on industrial demand, and fields that constituted the basic strength of industry at the time, such as metals, chemicals, electronics, machinery, and food, became the core.

What was decisive was talent and autonomy.

Korean scientists who had been working in the United States and Europe returned in large numbers, and the government provided KIST with research autonomy and bold financial support.

The operating system, free from audits or government approvals, and the salary and research environment, which were exceptional for the time, created a new research ecosystem that did not exist in Korea.

This system became the basic grammar of Korean science and technology policy for the following decades.

The results quickly translated into industrial achievements. KIST spearheaded the domestic production of technologies that were previously dependent on imports, such as magnetic tape, freon gas, and copper-clad steel wire, and numerous companies grew based on these technologies.

Looking at the bigger picture, KIST was involved in the initial design of the POSCO, shipbuilding, electronics, and automobile industries.

The steel mill construction plan, in which these metallurgists participated, became the starting point for POSCO, and as the steel-related industries took hold, the foundation for the heavy chemical industry was also established.

A circular structure has been formed in which research institutes create industries, and industries in turn expand research institutes.

This catch-up R&D model played a decisive role in tying Korea's industrialization strategy into a single system.

This allows the cycle of acquiring, applying, and improving technology to be repeated in short cycles at the national level.

The subsequent emergence of government-funded research institutes and Daedeok Special Zones can also be said to be an extension of this structure.

What KIST demonstrated was not simply technological development, but the fact that a nation can redefine the framework of an industrial nation through research institutes.

If Germany reorganized its regions into research institutes, Korea designed the foundation of its national strategy with research institutes.

The rise of the "global institution" called the research institute

The era of international cooperation supporting super-scale science

Today's research institutes are no longer national laboratories.

It is a massive operational mechanism that addresses global risks and challenges.

The unusually rapid development of a vaccine immediately following the pandemic was possible because research institutes and companies in the US, Europe, and Asia shared data, cross-validated technologies, and internationally divided clinical trials and production.

The same goes for space exploration and asteroid impact preparedness.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) are working together to manage space risks that cannot be addressed by a single country by integrating their observation capabilities and probes into separate systems.

Even ultra-large instruments like particle accelerators and gravitational wave observatories already require the combined funding, technology, and human resources of dozens of countries to maintain. CERN's Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is a prime example.

This trend is even more evident in climate change research.

Satellite observations, ocean and atmosphere monitoring, and long-term modeling only become meaningful when data from research institutes around the world are integrated into a network.

Beyond being a knowledge-producing institution, the institute has become an operational platform for addressing global issues.

What this change tells us is clear.

The point is that research institutes are no longer just national laboratories, but are now core platforms for global strategy.

International scientific cooperation is not just a matter of equipment and money.

Rather, it is the 'network of people' that is created through the interweaving of organization, culture, leadership, and movement of experts that is the essence.

It is at this point that the nature of the research institute begins to change significantly.

- Why we need to talk about the lab again today

Beyond investment uncertainty and political controversy, the future is first revealed in the lab.

The research lab has always been a difficult choice.

It costs a lot of money, the results are uncertain, and political controversy is inevitable.

Just as the National Science Foundation (NSF) was ridiculed in the 1970s for its basic research on topics like "Why do people fall in love?", research institutes are still constantly plagued by the question, "What's the use right now?"

But as time goes by, the context changes.

Studies that were once considered ridiculous have become core knowledge in psychology and brain science, and NSFNET, which was established by the NSF as a dedicated network for researchers, has led to today's Internet.

Slow investments made at points where utility was not visible eventually became the foundation of civilization.

This problem is acute in Korea as well.

The attraction of research institutes is always at the center of conflict due to inter-regional competition, political interests, and industrial advantages and disadvantages.

It's natural to wonder, "What can I really get out of this investment?"

But history shows a different truth.

Once properly established, a research institute becomes the root of technology, the source of industry, and the starting point of future infrastructure.

The knowledge created by the research institute will change the future 10 years from now, and the infrastructure built by the research institute will create the industry 30 years from now.

The choices that are causing controversy now will ultimately determine the pace of innovation in a country.

《Triumph of the Laboratory》 addresses that very scene head-on.

This study traces the origins of the research institute, why it always operates amid opposition and suspicion, and why, despite this, the future always begins in the research institute, going back and forth between world history and the reality of Korea.

This book does not glorify the institute or repeat the heroic narrative.

Instead, it shows the courage of a nation that made an uncertain investment, the competition between regions for the future, and the real-life clash between politics and science.

The reason we need to talk about the lab again today is clear.

The future is not determined by science and technology alone.

When industrial environments, institutional choices, and political imagination are combined, a completely different path opens up.

And the place where that choice first appears is the research lab.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 17, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 384 pages | 520g | 143*215*23mm

- ISBN13: 9788998243449

- ISBN10: 899824344X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)