This isn't science meant to be funny.

|

Description

Book Introduction

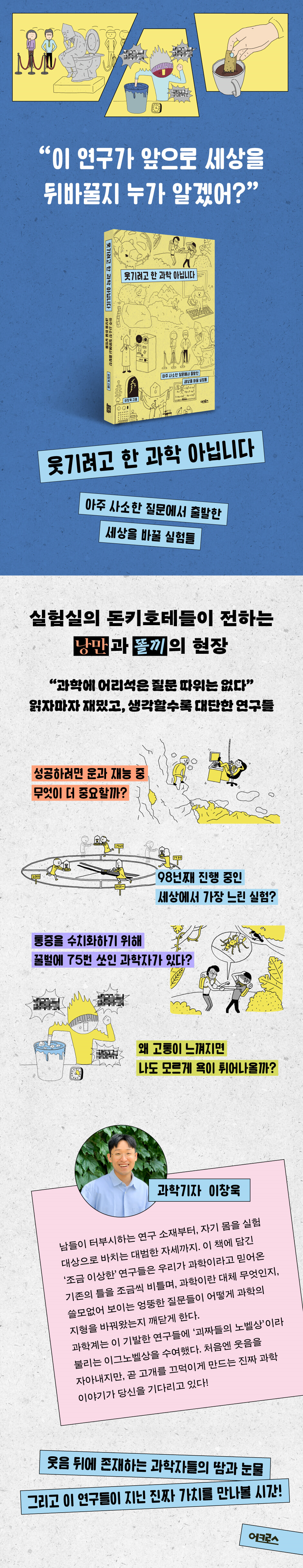

“There are no stupid questions in science.”

It's a study that makes you laugh out loud the moment you read it, and the more you think about it, the more amazing it becomes.

Here are scientists who, regardless of what the world defines as great, are diving into the questions they're curious about.

From research materials that others consider taboo, like feces and urine, to the daring attitude of offering one's own body as a subject for experimentation.

The research presented in this book, which may seem bewildering at first glance, gradually twists the existing framework we have believed to be science, making us realize what science really is and how seemingly useless and absurd questions have changed the landscape of science.

The scientific community awarded these ingenious studies the Ig Nobel Prizes, often called the "Nobel Prizes for Freaks."

If science begins with the question "Why?", this book shows how strange and bizarre that question can be.

[Science Dong-A] Reporter Lee Chang-wook tells a true science story that will make you laugh at first but soon nod your head.

It's a study that makes you laugh out loud the moment you read it, and the more you think about it, the more amazing it becomes.

Here are scientists who, regardless of what the world defines as great, are diving into the questions they're curious about.

From research materials that others consider taboo, like feces and urine, to the daring attitude of offering one's own body as a subject for experimentation.

The research presented in this book, which may seem bewildering at first glance, gradually twists the existing framework we have believed to be science, making us realize what science really is and how seemingly useless and absurd questions have changed the landscape of science.

The scientific community awarded these ingenious studies the Ig Nobel Prizes, often called the "Nobel Prizes for Freaks."

If science begins with the question "Why?", this book shows how strange and bizarre that question can be.

[Science Dong-A] Reporter Lee Chang-wook tells a true science story that will make you laugh at first but soon nod your head.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Prologue: There's some truly funny science out there.

PART 1: Strange and Embarrassing Questions

1 Why do wombats poop in the shape of dice?

2 How can I eat the most delicious potato chips?

Which part of the body would be most painful if stung by a 3-stroke?

4 Are cats liquid or solid?

5. Which is more important to success, luck or talent?

PART 2: The Usefulness of Seemingly Useless Science

6. I asked the mold to design the subway line.

7 Every word has meaning, even swear words

8 The world's slowest 98-year experiment

9 Smart Toilets That Wipe Out Your Prejudices

10 The Ig Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize are surprisingly close.

Epilogue: A Hymn to Strange Curiosity

PART 1: Strange and Embarrassing Questions

1 Why do wombats poop in the shape of dice?

2 How can I eat the most delicious potato chips?

Which part of the body would be most painful if stung by a 3-stroke?

4 Are cats liquid or solid?

5. Which is more important to success, luck or talent?

PART 2: The Usefulness of Seemingly Useless Science

6. I asked the mold to design the subway line.

7 Every word has meaning, even swear words

8 The world's slowest 98-year experiment

9 Smart Toilets That Wipe Out Your Prejudices

10 The Ig Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize are surprisingly close.

Epilogue: A Hymn to Strange Curiosity

Detailed image

Into the book

Why do most mammals have a consistent ratio of urethral length to diameter? In other words, why did everyone evolve to take 21 seconds to urinate? Professor Hoo speculated that this mystery might be related to animal survival.

To avoid external predators, the shorter the time it takes to urinate, the better.

As you know, the moment you relieve yourself is the time when you are most vulnerable to external threats (imagine someone attacking you while you are defecating).

(He's not even human).

The longer you spend urinating, the longer you are at risk of being discovered or attacked by predators.

The interesting thing is that drastically reducing the time it takes to urinate does not give you a survival advantage.

--- p.34~35 From “Chapter 1 Why do wombats poop in the shape of dice?”

Professor Spence's potato chip research, which became famous under the name of the 'sonic chip', impressed the Ig Nobel Prize committee with the sight of the experiment participants wearing headphones and chewing potato chips with very serious faces.

But the more important meaning is that it shows that the essence of 'taste' felt by humans is not limited to taste or smell.

The best potato chip 'taste experience' is created when the senses of taste (saltiness, oiliness), smell (the savory potato chip smell), touch (the rough feeling on the teeth and tongue tip), and hearing (crunch!) are all properly harmonized and combined.

Professor Spence asked me this question:

“Imagine having crispy potato chips and soggy potato chips in front of you.

Which would you choose? (Crispy potato chips, of course.) They are identical in taste, aroma, oiliness, and nutritional content.

The only difference is the crunchy sound.

Why are people drawn to crunchy potato chips when they have no nutritional value?” --- p.60 From “Chapter 2 How to Eat the Most Delicious Potato Chips”

The differences in the venom of stinging insects were a subject of endless exploration for Schmidt.

In the scientific field, poisons have mostly been studied from the perspective of medicine or pharmacology.

That is, the focus is on how to detoxify the poison and treat the patient, or whether there is a possibility that the poison can be used as medicine.

Schmidt, on the other hand, wondered what role venom might have played in insect evolution.

To understand this, we had to analyze the two basic properties of saliva and venom: 'toxicity' and 'pain'.

First and foremost, it's important to note that these two qualities, which people usually consider roughly similar, are completely separate.

'Toxicity' is the ability of a chemical to cause damage to a living organism, and 'pain' refers to the pain felt by a living organism.

--- p.72~73 From “Chapter 3: Which part of the body hurts the most when stung by a bee?”

In 2014, when the 'liquid cat theory' was circulating on the Internet, Marc-Antoine Fardin, a researcher at the Institute of Physics at the University of Lyon in France, considered the debate merely amusing.

But Pardin, a rheologist, soon began to wonder whether cats might actually be liquids.

First, let's introduce rheology, which is unfamiliar to most people.

Rheology is a subdiscipline of physics that studies how materials deform when they flow.

The name 'rheology' itself is derived from the Greek expression 'panta reiπ?ντα ?ε?' meaning "everything flows", a phrase attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus.

In classical physics, the force acting on a solid is explained by the property called 'elasticity', and the flow of liquids and gases is explained by the property called 'viscosity'.

--- p.95 From Chapter 4, “Is a cat a liquid or a solid?”

After publishing his research on the Peter Principle, Professor Pluckino continued to research more social and economic issues, finding ways in which life works differently than we might expect.

The part that particularly caught his attention was 'random selection'.

Who would have thought that promoting just anyone could be a better strategy than promoting the best employees?

He studied a variety of random strategies, ranging from randomly selected politicians to randomly selected investment and trading strategies.

Under the expression 'randomness', what he ultimately encountered was the keyword 'success'.

--- p.123 From “Chapter 5: Which is more important for success, luck or talent?”

Why are subway maps so complicated? It's not just wanderers who ponder this.

The designers who plan the route also have the same concerns.

Let's say one day you are given a project to design a new route.

It doesn't matter whether it's Seoul or Busan.

How can we lay new routes to transport people and goods as efficiently as possible?

A Japanese research team won the Ig Nobel Prize for the somewhat absurd idea of entrusting route design to non-human organisms.

The name of the creature is 'Physarum polycephalum'.

Sounds like a joke? Their research has revolutionized the study of what "intelligence" is.

--- p.140 From “Chapter 6: When I Entrusted Slime to Design the Subway Line”

Professor Stevens won the 2010 Ig Nobel Prize in recognition of his work in finding new ways to alleviate human suffering.

Perhaps unsurprisingly(?), the award he received was not the ‘Linguistics Prize’ but the ‘Peace Prize’.

Let's summarize his insights.

If you stub your big toe on the floor at dawn, you can swear a little.

Because that will actually reduce your suffering.

Even if life is painful, don't abuse your swearing.

This is because the pain-relieving effect of the curse is reduced.

This gives us one more reason to speak politely.

--- p.174 From “Chapter 7 All words have meaning, even swear words”

Although it was a simple experiment, the process was not simple.

Because I had to keep doing this until I was old to find out if I was going to get arthritis when I got older.

Whether it's rain or shine, or you're about to take an important exam or have a wedding or other life event, there's no exception when it comes to cracking your joints.

Indeed, he claimed to have done this consistently every day for 50 years.

In 1998, he wrote in a letter to the American journal Arthritis and Rheumatism, “I have bent the joints of my left hand at least 36,500 times, while I have barely bent the joints of my right hand.

However, there was no arthritis in either hand and there was no particular difference,” he said.

--- p.200 From “Chapter 8: The World’s Slowest 98-Year Experiment”

The most radical attempt was the 'anal fold recognition scanner'.

This was an idea that came from Researcher Park after hearing that Salvador Dali, a Spanish surrealist painter, had said, “Anal wrinkles look completely different for each person.”

It is said that the anal muscle folds are used as biometric information unique to each individual, such as fingerprints, irises, or blood vessels on the back of the hand.

To do this, the camera must observe the anus, and the smart toilet's AI must analyze the anus.

“Of course, there was a lot of backlash.

“People were very reluctant to show their sensitive parts, and ethical issues were raised about it.” --- p.228 From “Chapter 9: A Smart Toilet That Wipes Out Your Prejudices”

Looking at Andre Geim's research career, which led from the Ig Nobel Prize to the Nobel Prize, one wonders how one person could win both awards at the same time.

To most people, the Ig Nobel Prizes seem like a parody of the Nobel Prizes, far removed from the seriousness or urgency that scientific luminaries are expected to possess.

Isn't the Nobel Prize awarded for serious and outstanding research? How can an Ig Nobel Prize winner win a Nobel Prize? We could rephrase this question this way.

So, what kind of research is important research?

To avoid external predators, the shorter the time it takes to urinate, the better.

As you know, the moment you relieve yourself is the time when you are most vulnerable to external threats (imagine someone attacking you while you are defecating).

(He's not even human).

The longer you spend urinating, the longer you are at risk of being discovered or attacked by predators.

The interesting thing is that drastically reducing the time it takes to urinate does not give you a survival advantage.

--- p.34~35 From “Chapter 1 Why do wombats poop in the shape of dice?”

Professor Spence's potato chip research, which became famous under the name of the 'sonic chip', impressed the Ig Nobel Prize committee with the sight of the experiment participants wearing headphones and chewing potato chips with very serious faces.

But the more important meaning is that it shows that the essence of 'taste' felt by humans is not limited to taste or smell.

The best potato chip 'taste experience' is created when the senses of taste (saltiness, oiliness), smell (the savory potato chip smell), touch (the rough feeling on the teeth and tongue tip), and hearing (crunch!) are all properly harmonized and combined.

Professor Spence asked me this question:

“Imagine having crispy potato chips and soggy potato chips in front of you.

Which would you choose? (Crispy potato chips, of course.) They are identical in taste, aroma, oiliness, and nutritional content.

The only difference is the crunchy sound.

Why are people drawn to crunchy potato chips when they have no nutritional value?” --- p.60 From “Chapter 2 How to Eat the Most Delicious Potato Chips”

The differences in the venom of stinging insects were a subject of endless exploration for Schmidt.

In the scientific field, poisons have mostly been studied from the perspective of medicine or pharmacology.

That is, the focus is on how to detoxify the poison and treat the patient, or whether there is a possibility that the poison can be used as medicine.

Schmidt, on the other hand, wondered what role venom might have played in insect evolution.

To understand this, we had to analyze the two basic properties of saliva and venom: 'toxicity' and 'pain'.

First and foremost, it's important to note that these two qualities, which people usually consider roughly similar, are completely separate.

'Toxicity' is the ability of a chemical to cause damage to a living organism, and 'pain' refers to the pain felt by a living organism.

--- p.72~73 From “Chapter 3: Which part of the body hurts the most when stung by a bee?”

In 2014, when the 'liquid cat theory' was circulating on the Internet, Marc-Antoine Fardin, a researcher at the Institute of Physics at the University of Lyon in France, considered the debate merely amusing.

But Pardin, a rheologist, soon began to wonder whether cats might actually be liquids.

First, let's introduce rheology, which is unfamiliar to most people.

Rheology is a subdiscipline of physics that studies how materials deform when they flow.

The name 'rheology' itself is derived from the Greek expression 'panta reiπ?ντα ?ε?' meaning "everything flows", a phrase attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus.

In classical physics, the force acting on a solid is explained by the property called 'elasticity', and the flow of liquids and gases is explained by the property called 'viscosity'.

--- p.95 From Chapter 4, “Is a cat a liquid or a solid?”

After publishing his research on the Peter Principle, Professor Pluckino continued to research more social and economic issues, finding ways in which life works differently than we might expect.

The part that particularly caught his attention was 'random selection'.

Who would have thought that promoting just anyone could be a better strategy than promoting the best employees?

He studied a variety of random strategies, ranging from randomly selected politicians to randomly selected investment and trading strategies.

Under the expression 'randomness', what he ultimately encountered was the keyword 'success'.

--- p.123 From “Chapter 5: Which is more important for success, luck or talent?”

Why are subway maps so complicated? It's not just wanderers who ponder this.

The designers who plan the route also have the same concerns.

Let's say one day you are given a project to design a new route.

It doesn't matter whether it's Seoul or Busan.

How can we lay new routes to transport people and goods as efficiently as possible?

A Japanese research team won the Ig Nobel Prize for the somewhat absurd idea of entrusting route design to non-human organisms.

The name of the creature is 'Physarum polycephalum'.

Sounds like a joke? Their research has revolutionized the study of what "intelligence" is.

--- p.140 From “Chapter 6: When I Entrusted Slime to Design the Subway Line”

Professor Stevens won the 2010 Ig Nobel Prize in recognition of his work in finding new ways to alleviate human suffering.

Perhaps unsurprisingly(?), the award he received was not the ‘Linguistics Prize’ but the ‘Peace Prize’.

Let's summarize his insights.

If you stub your big toe on the floor at dawn, you can swear a little.

Because that will actually reduce your suffering.

Even if life is painful, don't abuse your swearing.

This is because the pain-relieving effect of the curse is reduced.

This gives us one more reason to speak politely.

--- p.174 From “Chapter 7 All words have meaning, even swear words”

Although it was a simple experiment, the process was not simple.

Because I had to keep doing this until I was old to find out if I was going to get arthritis when I got older.

Whether it's rain or shine, or you're about to take an important exam or have a wedding or other life event, there's no exception when it comes to cracking your joints.

Indeed, he claimed to have done this consistently every day for 50 years.

In 1998, he wrote in a letter to the American journal Arthritis and Rheumatism, “I have bent the joints of my left hand at least 36,500 times, while I have barely bent the joints of my right hand.

However, there was no arthritis in either hand and there was no particular difference,” he said.

--- p.200 From “Chapter 8: The World’s Slowest 98-Year Experiment”

The most radical attempt was the 'anal fold recognition scanner'.

This was an idea that came from Researcher Park after hearing that Salvador Dali, a Spanish surrealist painter, had said, “Anal wrinkles look completely different for each person.”

It is said that the anal muscle folds are used as biometric information unique to each individual, such as fingerprints, irises, or blood vessels on the back of the hand.

To do this, the camera must observe the anus, and the smart toilet's AI must analyze the anus.

“Of course, there was a lot of backlash.

“People were very reluctant to show their sensitive parts, and ethical issues were raised about it.” --- p.228 From “Chapter 9: A Smart Toilet That Wipes Out Your Prejudices”

Looking at Andre Geim's research career, which led from the Ig Nobel Prize to the Nobel Prize, one wonders how one person could win both awards at the same time.

To most people, the Ig Nobel Prizes seem like a parody of the Nobel Prizes, far removed from the seriousness or urgency that scientific luminaries are expected to possess.

Isn't the Nobel Prize awarded for serious and outstanding research? How can an Ig Nobel Prize winner win a Nobel Prize? We could rephrase this question this way.

So, what kind of research is important research?

--- p.253~254 From “Chapter 10: The Ig Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize are Surprisingly Close”

Publisher's Review

“There are no stupid questions in science.”

It's a study that makes you laugh out loud the moment you read it, and the more you think about it, the more amazing it becomes.

If you were a scientist, what would you want to study? A mysterious phenomenon like a black hole, or an experiment that will be remembered for generations, like the discovery of the Higgs boson? Whichever it is, you'd likely choose something that feels more impressive and impressive.

But here, there are scientists who bravely jump into the question they're curious about, regardless of what the world thinks is good.

For example, they are the ones who have explored questions like, "Where does a bee sting hurt the most?", "Why is wombat poop square?", and "Are cats solid or liquid?" more seriously than anyone else.

What on earth do these rather absurd and seemingly unremarkable studies mean?

When we think of science, we think of blackboards filled with complex formulas, solemn laboratories, and cutting-edge technologies that transform human lives.

But the starting point of science has always been very trivial questions that spring from pure curiosity.

The research in this book gradually twists the existing framework we have believed to be science, making us realize what science really is and how seemingly useless and absurd questions have changed the landscape of science.

The author of this book, Lee Chang-wook, a reporter for Science Dong-A, introduces research that has won the Ig Nobel Prize, which is called the Nobel Prize for eccentrics, and tells a true science story that will make you laugh at first but soon nod your head.

'A-level science' exists only when there is 'B-level science'.

A scene of romance and wit delivered by the Don Quixotes of the laboratory.

As a science journalist who has covered numerous scientific achievements, the author confesses that he has realized that behind so-called "A-level science" of academic importance, there has always been a free and creative soil of "B-level science."

I've witnessed meaningful follow-up research emerge and the boundaries of science expand amidst studies that deal with far-fetched topics, experimental methods so bizarre that they're too darn cool to be considered great research, and studies that are easily dismissed as B-grade science.

And right at the center of this B-grade science is the Ig Nobel Prize.

The Ig Nobel Prize is a parody of the Nobel Prize we are already familiar with, and is awarded for humorous research that is called “achievements that cannot and should not be repeated.”

So, when it was introduced to the public, more attention was paid to scenes that felt like scientists' eccentricities, such as 'showing up to receive an award wearing a toilet seat over his head' or 'going out into the wild and living like a goat for three days'.

But this book doesn't stop at simply consuming the Ig Nobel Prize as a 'funny story'; it takes a closer look at the blood, sweat, and tears of the scientists hidden behind the laughter.

When I see scientists who, despite public ridicule, scientifically study human excrement, a substance that has long been taboo, or ask single-celled organisms like slime mold to solve a maze, making us reconsider what "intelligence" is, I feel like Ig Nobel Prize-winning scientists are like Don Quixotes in the laboratory.

Here, complex experiments are made understandable at a glance with perfect metaphors, and author Lee Chang-wook's writing skills, which quickly breaks down the barriers to science by weaving jokes throughout the sentences, are added to create a science textbook that is "not meant to be funny, but very funny."

The first half of this book presents a feast of outrageous research that will make you laugh out loud and your jaw drop at the same time.

Science always begins with the question, "Why?" but various studies have shown that this question need not be grand or lofty.

The second half focuses on the need for institutional support for these ingenious experiments, examining why, in our performance-driven modern society, we must preserve the difficult-to-defend value of strange curiosity.

“Which is more important in success: luck or talent?”

Speaking of the usefulness of seemingly useless research

Humans find utility in everything.

Science is no exception.

So, many researchers are asked questions like, “But what is the use of researching this?”

David Hu, a fluid dynamicist and two-time Ig Nobel Prize winner, was changing his son's diaper one day when he got wet on his chest.

He started counting in his head to calm his anger and discovered that a 4.5-kilogram baby peed in 21 seconds.

It also took him 23 seconds to empty his bladder.

The urine output of a newborn baby and an adult male can differ by almost a factor of 10, yet the time it takes to urinate differs by only 2 seconds.

This moist discovery soon led to the question, “Is the urination time of animals constant regardless of body weight?” and he and his colleague Patricia Yang began looking at urine from a fluid dynamics perspective.

Until then, there had been virtually no research that had fully introduced fluid dynamics methodology to the urinary system.

This study not only signals the development of a new field called biofluidics, which examines the fluid dynamics of the human body, such as the blood flowing through blood vessels, but also provides us with this insight.

“Imagine you went to the bathroom and it took you one minute to urinate instead of 21 seconds.

This clearly means there is a health problem.” (p. 43)

On the other hand, there are studies that make you wonder, 'Is this even in the realm of science?'

We often refer to successful people as 'lucky people' or 'talented people'.

So, which factor is more important in success: luck or talent? Professor Alessandro Pluchino, a theoretical physicist, conducted an experiment using computer simulations.

1,000 people with different talents were exposed to random events of good and bad luck.

What was the result? After 40 years inside the computer, most people were very poor, and only a few people had much more money than when they started.

What we should note is that the few who amassed wealth were people of average talent.

The reason they were rich was simply because they encountered more luck than bad luck during the simulation process.

Professor Pluckino's research on complex systems modeling challenges the myth of meritocracy through the methodology of physics, while offering the following advice on the secret to 'success':

“My suggestion is that to get lucky, you should try as many opportunities as possible.

“This is the only way to achieve success.” (p. 131) Couldn’t his advice be applied to the scientific community as well?

To achieve one great study that will change the world, we must ultimately support more and more diverse research and build systems that enable it.

The usefulness of research that seems useless can be found there.

The Ig Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize are surprisingly close.

What if we gave 1 percent of the science budget to some weird people?

There is only one scientist in this world who has received both the Nobel Prize and the Ig Nobel Prize.

The protagonist is Russian physicist André Geim.

How is it possible to receive two awards that illuminate both the heart and the fringes of science? The common denominator lies in Gaim's unique lab culture, known as the "Friday Night Experiment."

I dedicated Friday nights to working on side projects unrelated to my main project.

It accounted for a whopping 10 percent of the lab's total working hours.

The goal was to conduct research that focused on 'fun', even if it was not my area of expertise.

I have worked on about 20 projects over the past 15 years, most of which have failed, but I have had three successes.

The first of these was the 'frog levitation experiment', which won Gaim the Ig Nobel Prize, and was made possible by a rather absurd attempt to pour water into the middle of expensive experimental equipment.

Also, the 'graphene extraction experiment' that won the Nobel Prize was able to succeed through an unexpected approach of peeling off graphene by attaching Scotch tape to graphite and then removing it.

After winning the Nobel Prize, Gaim is said to have said to people that a sense of humor is a necessary virtue for a scientist.

If you want to win a Nobel Prize, first win an Ig Nobel Prize.

As the Nobel Prize award season approaches, discussions about why Korea has not been able to produce Nobel Prize winners in the field of science suddenly begin to pour in.

Perhaps, rather than focusing on which research is more likely to win a Nobel Prize, we should be more concerned with how our society protects the values of curiosity and imagination.

James Lovelock, the British scientist who created the Gaia theory, once argued that just 1 percent of the national science budget should be invested in unorthodox research.

When institutional guarantees are made for basic research and scientific diversity, and a more tolerant social atmosphere is formed, we will be able to achieve another groundbreaking breakthrough that will transform human life, like the invention of the internet or vaccines.

In the book's epilogue, the author recounts a conversation he had with Mark Abrahams, founder of the Ig Nobel Prizes.

When asked how Korea could win more Ig Nobel Prizes, Abrahams mentioned the UK and Japan, which have won the most Ig Nobel Prizes, and said that it might be because of the atmosphere in those countries that tolerates even the most outlandish ideas.

“No one can easily predict what kind of ripple effects a single study will have or how it will change human life,” the author says.

Science is a story whose origins are unknown to anyone.

I hope this book will lead us into more absurd questions.

It's a study that makes you laugh out loud the moment you read it, and the more you think about it, the more amazing it becomes.

If you were a scientist, what would you want to study? A mysterious phenomenon like a black hole, or an experiment that will be remembered for generations, like the discovery of the Higgs boson? Whichever it is, you'd likely choose something that feels more impressive and impressive.

But here, there are scientists who bravely jump into the question they're curious about, regardless of what the world thinks is good.

For example, they are the ones who have explored questions like, "Where does a bee sting hurt the most?", "Why is wombat poop square?", and "Are cats solid or liquid?" more seriously than anyone else.

What on earth do these rather absurd and seemingly unremarkable studies mean?

When we think of science, we think of blackboards filled with complex formulas, solemn laboratories, and cutting-edge technologies that transform human lives.

But the starting point of science has always been very trivial questions that spring from pure curiosity.

The research in this book gradually twists the existing framework we have believed to be science, making us realize what science really is and how seemingly useless and absurd questions have changed the landscape of science.

The author of this book, Lee Chang-wook, a reporter for Science Dong-A, introduces research that has won the Ig Nobel Prize, which is called the Nobel Prize for eccentrics, and tells a true science story that will make you laugh at first but soon nod your head.

'A-level science' exists only when there is 'B-level science'.

A scene of romance and wit delivered by the Don Quixotes of the laboratory.

As a science journalist who has covered numerous scientific achievements, the author confesses that he has realized that behind so-called "A-level science" of academic importance, there has always been a free and creative soil of "B-level science."

I've witnessed meaningful follow-up research emerge and the boundaries of science expand amidst studies that deal with far-fetched topics, experimental methods so bizarre that they're too darn cool to be considered great research, and studies that are easily dismissed as B-grade science.

And right at the center of this B-grade science is the Ig Nobel Prize.

The Ig Nobel Prize is a parody of the Nobel Prize we are already familiar with, and is awarded for humorous research that is called “achievements that cannot and should not be repeated.”

So, when it was introduced to the public, more attention was paid to scenes that felt like scientists' eccentricities, such as 'showing up to receive an award wearing a toilet seat over his head' or 'going out into the wild and living like a goat for three days'.

But this book doesn't stop at simply consuming the Ig Nobel Prize as a 'funny story'; it takes a closer look at the blood, sweat, and tears of the scientists hidden behind the laughter.

When I see scientists who, despite public ridicule, scientifically study human excrement, a substance that has long been taboo, or ask single-celled organisms like slime mold to solve a maze, making us reconsider what "intelligence" is, I feel like Ig Nobel Prize-winning scientists are like Don Quixotes in the laboratory.

Here, complex experiments are made understandable at a glance with perfect metaphors, and author Lee Chang-wook's writing skills, which quickly breaks down the barriers to science by weaving jokes throughout the sentences, are added to create a science textbook that is "not meant to be funny, but very funny."

The first half of this book presents a feast of outrageous research that will make you laugh out loud and your jaw drop at the same time.

Science always begins with the question, "Why?" but various studies have shown that this question need not be grand or lofty.

The second half focuses on the need for institutional support for these ingenious experiments, examining why, in our performance-driven modern society, we must preserve the difficult-to-defend value of strange curiosity.

“Which is more important in success: luck or talent?”

Speaking of the usefulness of seemingly useless research

Humans find utility in everything.

Science is no exception.

So, many researchers are asked questions like, “But what is the use of researching this?”

David Hu, a fluid dynamicist and two-time Ig Nobel Prize winner, was changing his son's diaper one day when he got wet on his chest.

He started counting in his head to calm his anger and discovered that a 4.5-kilogram baby peed in 21 seconds.

It also took him 23 seconds to empty his bladder.

The urine output of a newborn baby and an adult male can differ by almost a factor of 10, yet the time it takes to urinate differs by only 2 seconds.

This moist discovery soon led to the question, “Is the urination time of animals constant regardless of body weight?” and he and his colleague Patricia Yang began looking at urine from a fluid dynamics perspective.

Until then, there had been virtually no research that had fully introduced fluid dynamics methodology to the urinary system.

This study not only signals the development of a new field called biofluidics, which examines the fluid dynamics of the human body, such as the blood flowing through blood vessels, but also provides us with this insight.

“Imagine you went to the bathroom and it took you one minute to urinate instead of 21 seconds.

This clearly means there is a health problem.” (p. 43)

On the other hand, there are studies that make you wonder, 'Is this even in the realm of science?'

We often refer to successful people as 'lucky people' or 'talented people'.

So, which factor is more important in success: luck or talent? Professor Alessandro Pluchino, a theoretical physicist, conducted an experiment using computer simulations.

1,000 people with different talents were exposed to random events of good and bad luck.

What was the result? After 40 years inside the computer, most people were very poor, and only a few people had much more money than when they started.

What we should note is that the few who amassed wealth were people of average talent.

The reason they were rich was simply because they encountered more luck than bad luck during the simulation process.

Professor Pluckino's research on complex systems modeling challenges the myth of meritocracy through the methodology of physics, while offering the following advice on the secret to 'success':

“My suggestion is that to get lucky, you should try as many opportunities as possible.

“This is the only way to achieve success.” (p. 131) Couldn’t his advice be applied to the scientific community as well?

To achieve one great study that will change the world, we must ultimately support more and more diverse research and build systems that enable it.

The usefulness of research that seems useless can be found there.

The Ig Nobel Prize and the Nobel Prize are surprisingly close.

What if we gave 1 percent of the science budget to some weird people?

There is only one scientist in this world who has received both the Nobel Prize and the Ig Nobel Prize.

The protagonist is Russian physicist André Geim.

How is it possible to receive two awards that illuminate both the heart and the fringes of science? The common denominator lies in Gaim's unique lab culture, known as the "Friday Night Experiment."

I dedicated Friday nights to working on side projects unrelated to my main project.

It accounted for a whopping 10 percent of the lab's total working hours.

The goal was to conduct research that focused on 'fun', even if it was not my area of expertise.

I have worked on about 20 projects over the past 15 years, most of which have failed, but I have had three successes.

The first of these was the 'frog levitation experiment', which won Gaim the Ig Nobel Prize, and was made possible by a rather absurd attempt to pour water into the middle of expensive experimental equipment.

Also, the 'graphene extraction experiment' that won the Nobel Prize was able to succeed through an unexpected approach of peeling off graphene by attaching Scotch tape to graphite and then removing it.

After winning the Nobel Prize, Gaim is said to have said to people that a sense of humor is a necessary virtue for a scientist.

If you want to win a Nobel Prize, first win an Ig Nobel Prize.

As the Nobel Prize award season approaches, discussions about why Korea has not been able to produce Nobel Prize winners in the field of science suddenly begin to pour in.

Perhaps, rather than focusing on which research is more likely to win a Nobel Prize, we should be more concerned with how our society protects the values of curiosity and imagination.

James Lovelock, the British scientist who created the Gaia theory, once argued that just 1 percent of the national science budget should be invested in unorthodox research.

When institutional guarantees are made for basic research and scientific diversity, and a more tolerant social atmosphere is formed, we will be able to achieve another groundbreaking breakthrough that will transform human life, like the invention of the internet or vaccines.

In the book's epilogue, the author recounts a conversation he had with Mark Abrahams, founder of the Ig Nobel Prizes.

When asked how Korea could win more Ig Nobel Prizes, Abrahams mentioned the UK and Japan, which have won the most Ig Nobel Prizes, and said that it might be because of the atmosphere in those countries that tolerates even the most outlandish ideas.

“No one can easily predict what kind of ripple effects a single study will have or how it will change human life,” the author says.

Science is a story whose origins are unknown to anyone.

I hope this book will lead us into more absurd questions.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: June 23, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 288 pages | 438g | 140*210*18mm

- ISBN13: 9791167742148

- ISBN10: 1167742141

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)