If you look at the world through the language of mathematics

|

Description

Book Introduction

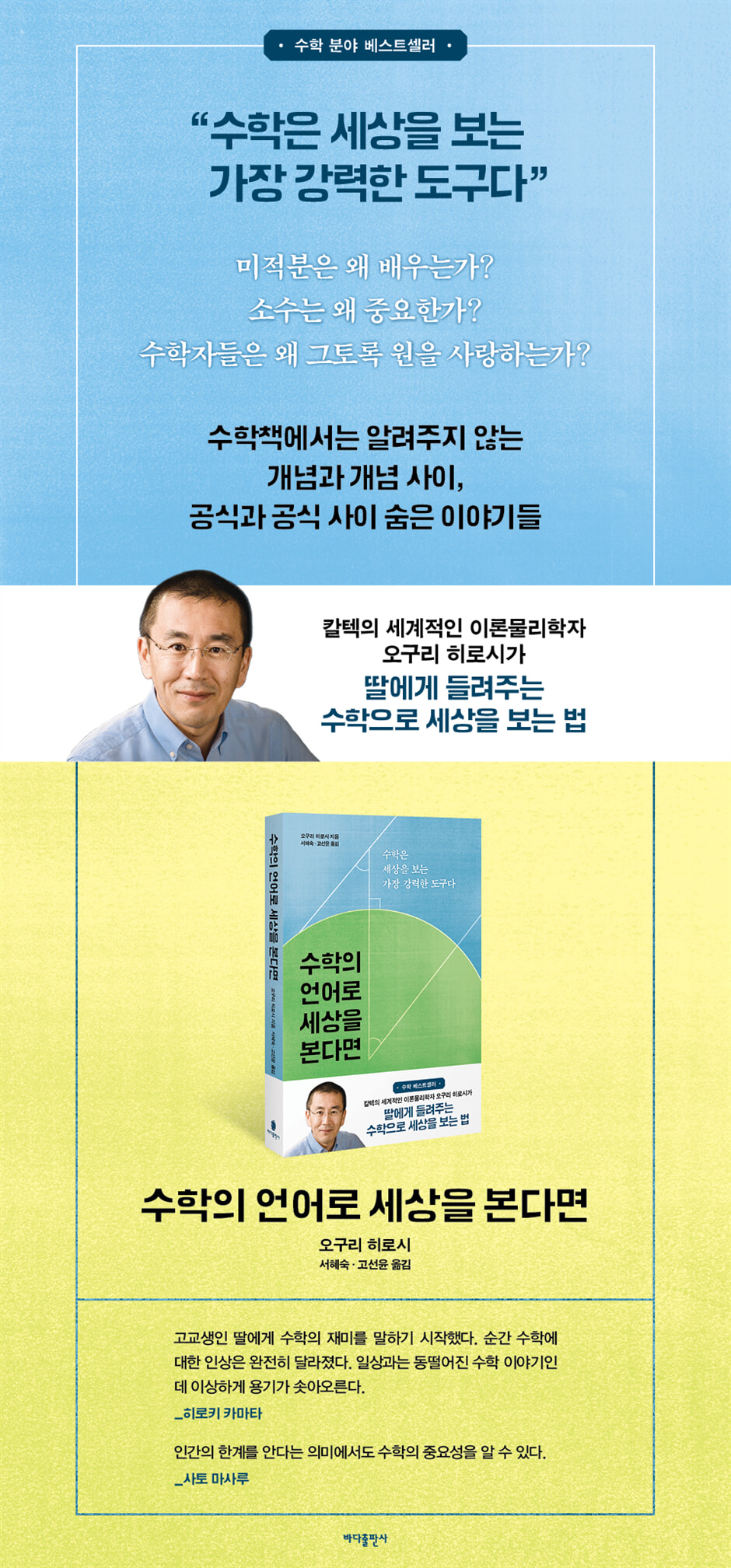

Hiroshi Oguri, a world-renowned theoretical physicist at Caltech,

How to See the World Through Math, Taught to My Daughter

A mathematical commentary by Hiroshi Oguri, a professor at the California Institute of Technology who has achieved world-renowned fame for his research on string theory.

Why are decimals important? Why does multiplying a negative by a negative result in a positive number? How do the formulas for solving equations come about, and why do we need to memorize them? Why do we need to know negative numbers, imaginary numbers, exponents, and logarithms? Hiroshi Oguri explains the fundamental principles of mathematics step by step for his high school-bound daughter, demonstrating how crucial a tool mathematics is for survival in the 21st century.

As we learn mathematics, we come to understand how mathematics is close to our daily lives and how it can be a powerful tool for viewing the world through questions we once wanted to ask and stories that were not covered in mathematics textbooks.

How to See the World Through Math, Taught to My Daughter

A mathematical commentary by Hiroshi Oguri, a professor at the California Institute of Technology who has achieved world-renowned fame for his research on string theory.

Why are decimals important? Why does multiplying a negative by a negative result in a positive number? How do the formulas for solving equations come about, and why do we need to memorize them? Why do we need to know negative numbers, imaginary numbers, exponents, and logarithms? Hiroshi Oguri explains the fundamental principles of mathematics step by step for his high school-bound daughter, demonstrating how crucial a tool mathematics is for survival in the 21st century.

As we learn mathematics, we come to understand how mathematics is close to our daily lives and how it can be a powerful tool for viewing the world through questions we once wanted to ask and stories that were not covered in mathematics textbooks.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface _ Mathematics from a Father to His Daughter

Chapter 1: Making Judgments with Uncertain Information

O.

J. Simpson trial, defense professor's argument │ First, let's roll the dice │ How not to lose in gambling │ Conditional probability and Bayes' theorem │ Is it worth getting a breast cancer screening? │ Learning 'learning from experience' mathematically │ The probability of a major nuclear power plant accident occurring again │ O.

Did J. Simpson kill his wife?

Chapter 2: Returning to Basic Principles

What's needed for technological innovation │ Addition, multiplication, and the three rules │ Subtraction, and the discovery of zero │ Why does (-1) × (-1) equal 1? │ Anything can be divided if there's a fraction │ Improper fraction → Mixed number → Continued fraction │ Making a calendar with continued fractions │ 'Irrational numbers' that I really didn't want to admit │ The splendid history of quadratic equations

Chapter 3: Big Capitals Are Not Fearful

The world's first atomic bomb test and the Fermi Estimate │ How much did atmospheric carbon dioxide increase? │ Don't be afraid of big numbers │ The secret weapon that doubled an astronomer's lifespan │ How to maximize compound interest savings? │ How many years does it take to double a bank deposit? │ The laws of nature are understood through algebra.

Chapter 4: The Wonders of the Minor

The Flower of Pure Mathematics │ Discovering Prime Numbers with the Sieve of Eratosthenes │ There are an Infinite Number of Prime Numbers │ There is a Pattern in the Occurrence of Prime Numbers │ Determining Prime Numbers with Pascal's Triangle │ Passing the Fermat Test Means You Are a Prime Number │ What is Public Key Cryptography, Which Protects Communication Secrets? │ Public Key Cryptography is the Key, Euler's Theorem │ Exchanging Credit Card Numbers

Chapter 5: Infinite Worlds and Imperfection

Welcome to Hotel California! │ '1=0.99999...' is unacceptable? │ Can't Achilles catch up with the tortoise? │ 'I'm lying now' │ 'Alibi proof' is 'reductio ad absurdum' │ This is Gödel's incompleteness theorem!

Chapter 6: Measuring the Shape of the Universe

How did the ancient Greeks measure the size of the Earth? │ The basics of the basics, the properties of triangles │ The groundbreaking idea of Cartesian coordinates │ Even in six, nine, or ten dimensions │ A world where Euclidean axioms do not hold │ A world where only the parallel axiom does not hold │ The 'wonderful theorem' that allows us to know the shape without looking from the outside │ Draw a triangle with one side 10 billion light-years long

Chapter 7 Calculus starts with integration

Letter from Archimedes │ Why 'integration first'? │ How do you calculate the original area? │ Any shape is OK, 'Archimedes' quadrature' │ What is being calculated in 'integration'? │ Let's integrate various functions │ Is a flying arrow at rest? │ Differentiation is the inverse of integration │ Differentiation and integration of exponential functions

Chapter 8: The "Imaginary Number" That Really Exists

Fantasy numbers, fantasy friends │ 'Numbers that become negative when squared' that always appear │ From one-dimensional real numbers to two-dimensional complex numbers │ Multiplication of complex numbers is 'increasing by rounding' │ 'Addition theorem' that leads to multiplication │ Geometric problems solved with equations! │ Euler's formula that connects trigonometric and exponential functions

Chapter 9: Measuring Difficulty and Beauty

Galois, 20 Years of Life and Immortal Achievements │ What is the symmetry of figures? │ The discovery of 'groups' │ The secret of the 'solution formula' for quadratic equations │ Why can cubic equations be solved? │ What does it mean to be able to 'solve an equation'? │ The quintic equation and the regular icosahedron │ A letter from Galois │ The difficulty of equations and the beauty of form │ Gaining another soul

Reviews

Chapter 1: Making Judgments with Uncertain Information

O.

J. Simpson trial, defense professor's argument │ First, let's roll the dice │ How not to lose in gambling │ Conditional probability and Bayes' theorem │ Is it worth getting a breast cancer screening? │ Learning 'learning from experience' mathematically │ The probability of a major nuclear power plant accident occurring again │ O.

Did J. Simpson kill his wife?

Chapter 2: Returning to Basic Principles

What's needed for technological innovation │ Addition, multiplication, and the three rules │ Subtraction, and the discovery of zero │ Why does (-1) × (-1) equal 1? │ Anything can be divided if there's a fraction │ Improper fraction → Mixed number → Continued fraction │ Making a calendar with continued fractions │ 'Irrational numbers' that I really didn't want to admit │ The splendid history of quadratic equations

Chapter 3: Big Capitals Are Not Fearful

The world's first atomic bomb test and the Fermi Estimate │ How much did atmospheric carbon dioxide increase? │ Don't be afraid of big numbers │ The secret weapon that doubled an astronomer's lifespan │ How to maximize compound interest savings? │ How many years does it take to double a bank deposit? │ The laws of nature are understood through algebra.

Chapter 4: The Wonders of the Minor

The Flower of Pure Mathematics │ Discovering Prime Numbers with the Sieve of Eratosthenes │ There are an Infinite Number of Prime Numbers │ There is a Pattern in the Occurrence of Prime Numbers │ Determining Prime Numbers with Pascal's Triangle │ Passing the Fermat Test Means You Are a Prime Number │ What is Public Key Cryptography, Which Protects Communication Secrets? │ Public Key Cryptography is the Key, Euler's Theorem │ Exchanging Credit Card Numbers

Chapter 5: Infinite Worlds and Imperfection

Welcome to Hotel California! │ '1=0.99999...' is unacceptable? │ Can't Achilles catch up with the tortoise? │ 'I'm lying now' │ 'Alibi proof' is 'reductio ad absurdum' │ This is Gödel's incompleteness theorem!

Chapter 6: Measuring the Shape of the Universe

How did the ancient Greeks measure the size of the Earth? │ The basics of the basics, the properties of triangles │ The groundbreaking idea of Cartesian coordinates │ Even in six, nine, or ten dimensions │ A world where Euclidean axioms do not hold │ A world where only the parallel axiom does not hold │ The 'wonderful theorem' that allows us to know the shape without looking from the outside │ Draw a triangle with one side 10 billion light-years long

Chapter 7 Calculus starts with integration

Letter from Archimedes │ Why 'integration first'? │ How do you calculate the original area? │ Any shape is OK, 'Archimedes' quadrature' │ What is being calculated in 'integration'? │ Let's integrate various functions │ Is a flying arrow at rest? │ Differentiation is the inverse of integration │ Differentiation and integration of exponential functions

Chapter 8: The "Imaginary Number" That Really Exists

Fantasy numbers, fantasy friends │ 'Numbers that become negative when squared' that always appear │ From one-dimensional real numbers to two-dimensional complex numbers │ Multiplication of complex numbers is 'increasing by rounding' │ 'Addition theorem' that leads to multiplication │ Geometric problems solved with equations! │ Euler's formula that connects trigonometric and exponential functions

Chapter 9: Measuring Difficulty and Beauty

Galois, 20 Years of Life and Immortal Achievements │ What is the symmetry of figures? │ The discovery of 'groups' │ The secret of the 'solution formula' for quadratic equations │ Why can cubic equations be solved? │ What does it mean to be able to 'solve an equation'? │ The quintic equation and the regular icosahedron │ A letter from Galois │ The difficulty of equations and the beauty of form │ Gaining another soul

Reviews

Detailed image

Into the book

Let's think about multiplying negative numbers by negative numbers.

Let's say you buy a 100 won juice on your way home from school every day.

This time, they say there is no allowance.

Your savings will decrease by 100 won every day.

After one day, it decreases by 100 won, and after two days, it decreases by 200 won.

After n days, 100 x n won is reduced.

This can be expressed as (-100)×n.

What if, for the case a day ago, n=-1?

Since I bought and drank a 100 won juice every day, my savings decreased by 100 won, so I would have had 100 won more in savings yesterday than today.

That is, (-100)×(-1)=100.

The day before yesterday, when n=-2, there would have been 200 won more, so (-100)×(-2)=200.

You can expect that if you multiply a negative number by a negative number, you get a positive number.

--- p.55

In July 1945, the world's first atomic bomb test was conducted at the Trinity Test Site in New Mexico, USA.

Enrico Fermi, who had built a nuclear reactor at the University of Chicago three years earlier, enabling a sustained chain reaction of nuclear fission, also participated in experiments as part of the Manhattan Project.

The storm reached the observation base 40 seconds after the explosion.

Fermi, who had been looking at the spot where the explosion had occurred, stood up and raised both hands above his head.

In his hand was a notepad he had prepared in advance.

As the storm arrived, he spread his arms.

The piece of paper flew about two and a half meters and fell to the ground.

Fermi, seeing this, thought for a moment, then looked at the participants and said:

“It has the power equivalent to 20,000 tons of TNT.”

--- p.81

I knew there were an infinite number of prime numbers, but I didn't know the prime numbers.

2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43…

If we list them like this, wouldn't there be some pattern? This problem has fascinated mathematicians from ancient Greece to the present day.

I think finding patterns in prime numbers is like finding the periodic table of atoms.

When 19th-century chemist Dmitri Mendeleev arranged the elements discovered so far in order of their atomic weights, he noticed that their properties followed periodic patterns.

With that periodicity, he predicted the existence of a new atom.

And Mendeleev's periodic table had a great influence on the elucidation of atomic structure in the 20th century.

Likewise, if we understand the patterns of prime numbers, which are the atoms of numbers, we can expect to be able to more deeply elucidate the secrets of numbers.

--- p.116~117

If you can't understand 1=0.99999… then what is the difference between these two numbers?

As we saw in Chapter 2, if we apply the basic rules of addition and subtraction, then if ab=0, then a=b.

Therefore, if 1-0.99999… = 0, then we cannot deny that 1=0.99999… as well.

So what if 1-0.99999… isn't 0? Then the question becomes, what exactly is the difference between 1 and 0.99999…?

If you think about it, the notation of infinite decimals like 0.99999… is somehow unsettling.

What originally goes into '...'? As finite beings, we cannot immediately understand the infinite decimals, which are an infinite number of numbers.

So let's consider a sequence of finite prime numbers that we can understand: 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, 0.9999.

A series of numbers like this is called a 'sequence'.

If we calculate the difference between this sequence and 1, we get the following:

--- p.157

In high school mathematics, almost all textbooks explain differentiation first and then introduce indefinite integrals as their inverse operation.

And the definite integral for calculating the area is defined as the difference of indefinite integrals.

This order makes sense in the sense that it teaches complete mathematics logically, but it is the opposite in terms of historical development.

Archimedes studied integration to calculate area in the 3rd century BC, and Newton and Leibniz devised differentiation in the 17th century.

There is a gap of more than 1800 years between the two periods.

There is a reason why integration was discovered first historically.

Integration is directly related to calculating visible quantities such as area and volume.

On the other hand, in the case of differentiation, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of concepts such as infinite decimals and limits.

For example, the speed of a moving object can be defined by differentiation, but in ancient Greece, the concept of limits was not yet established, so Zeno's paradox, which is later discussed as 'an arrow in flight is at rest', became a problem.

Differentiation is a more 'high-level' mathematical concept.

Let's say you buy a 100 won juice on your way home from school every day.

This time, they say there is no allowance.

Your savings will decrease by 100 won every day.

After one day, it decreases by 100 won, and after two days, it decreases by 200 won.

After n days, 100 x n won is reduced.

This can be expressed as (-100)×n.

What if, for the case a day ago, n=-1?

Since I bought and drank a 100 won juice every day, my savings decreased by 100 won, so I would have had 100 won more in savings yesterday than today.

That is, (-100)×(-1)=100.

The day before yesterday, when n=-2, there would have been 200 won more, so (-100)×(-2)=200.

You can expect that if you multiply a negative number by a negative number, you get a positive number.

--- p.55

In July 1945, the world's first atomic bomb test was conducted at the Trinity Test Site in New Mexico, USA.

Enrico Fermi, who had built a nuclear reactor at the University of Chicago three years earlier, enabling a sustained chain reaction of nuclear fission, also participated in experiments as part of the Manhattan Project.

The storm reached the observation base 40 seconds after the explosion.

Fermi, who had been looking at the spot where the explosion had occurred, stood up and raised both hands above his head.

In his hand was a notepad he had prepared in advance.

As the storm arrived, he spread his arms.

The piece of paper flew about two and a half meters and fell to the ground.

Fermi, seeing this, thought for a moment, then looked at the participants and said:

“It has the power equivalent to 20,000 tons of TNT.”

--- p.81

I knew there were an infinite number of prime numbers, but I didn't know the prime numbers.

2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 37, 41, 43…

If we list them like this, wouldn't there be some pattern? This problem has fascinated mathematicians from ancient Greece to the present day.

I think finding patterns in prime numbers is like finding the periodic table of atoms.

When 19th-century chemist Dmitri Mendeleev arranged the elements discovered so far in order of their atomic weights, he noticed that their properties followed periodic patterns.

With that periodicity, he predicted the existence of a new atom.

And Mendeleev's periodic table had a great influence on the elucidation of atomic structure in the 20th century.

Likewise, if we understand the patterns of prime numbers, which are the atoms of numbers, we can expect to be able to more deeply elucidate the secrets of numbers.

--- p.116~117

If you can't understand 1=0.99999… then what is the difference between these two numbers?

As we saw in Chapter 2, if we apply the basic rules of addition and subtraction, then if ab=0, then a=b.

Therefore, if 1-0.99999… = 0, then we cannot deny that 1=0.99999… as well.

So what if 1-0.99999… isn't 0? Then the question becomes, what exactly is the difference between 1 and 0.99999…?

If you think about it, the notation of infinite decimals like 0.99999… is somehow unsettling.

What originally goes into '...'? As finite beings, we cannot immediately understand the infinite decimals, which are an infinite number of numbers.

So let's consider a sequence of finite prime numbers that we can understand: 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, 0.9999.

A series of numbers like this is called a 'sequence'.

If we calculate the difference between this sequence and 1, we get the following:

--- p.157

In high school mathematics, almost all textbooks explain differentiation first and then introduce indefinite integrals as their inverse operation.

And the definite integral for calculating the area is defined as the difference of indefinite integrals.

This order makes sense in the sense that it teaches complete mathematics logically, but it is the opposite in terms of historical development.

Archimedes studied integration to calculate area in the 3rd century BC, and Newton and Leibniz devised differentiation in the 17th century.

There is a gap of more than 1800 years between the two periods.

There is a reason why integration was discovered first historically.

Integration is directly related to calculating visible quantities such as area and volume.

On the other hand, in the case of differentiation, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of concepts such as infinite decimals and limits.

For example, the speed of a moving object can be defined by differentiation, but in ancient Greece, the concept of limits was not yet established, so Zeno's paradox, which is later discussed as 'an arrow in flight is at rest', became a problem.

Differentiation is a more 'high-level' mathematical concept.

--- p.226~227

Publisher's Review

“Mathematics is everywhere in our daily lives.”

How to see the world through mathematics

Mathematics, which has been growing since ancient Greece, is everywhere in our daily lives.

Therefore, understanding mathematics is like acquiring a new language to read the world.

In Chapter 1, "Judging with Uncertain Information," Hiroshi Oguri calculates how much the odds of winning in gambling increase when the odds are slightly in your favor.

For example, if I have a 3% advantage over my opponent and continue to bet with enough money, my chances of doubling my stake go up to 99.75%.

In other words, in gambling, if you start with enough money when you have even the slightest advantage, you are almost certain to win. This fact can also be applied to how long we live.

For example, improving our daily habits, such as eating a balanced diet, exercising appropriately, and living a regular life, can significantly increase our chances of living a long life by giving us a 'slight advantage' in our chances of living a long life.

The power of mathematics is that it can clearly express in numbers how much this probability increases!

After all, mathematics is a discipline born out of necessity.

Since ancient times, wherever civilization developed, mathematics has always been present and has served as the foundation of civilization.

Mathematics, which may seem distant and unfamiliar, is actually directly connected to our lives.

For example, 'continued fractions', which are created by converting the denominator back into a fraction and then connecting unit fractions, have been used to make calendars.

If we assume that one year is approximately 365.24219 days and do a fractional approximation, 365.24219 is 365+0.024219≒365+1/4, so we can think of a calendar that has February 29th once every four years.

But in this case, there is an error of 0.00781 days.

Therefore, the Gregorian calendar we use today is a calendar created according to the rule that 'years divisible by 4 are leap years, but years divisible by 100 but not by 400 are not leap years.'

Even 'prime numbers', which seem to be the exclusive domain of mathematicians, are deeply rooted in our lives.

Prime numbers, also called the 'atoms of numbers' because they hold the secrets of numbers, are a concept that has fascinated mathematicians from ancient Greece to the present day.

Mathematicians are studying the patterns of appearance of prime numbers and methods for determining prime numbers, but there are still many unsolved problems related to prime numbers.

Nevertheless, minorities are used urgently in our lives.

The encryption system used for shopping or making payments on the Internet was developed by applying the properties of prime numbers.

Until now, no matter how complex the encryption technology was, it could be quickly broken once the rules of the encryption were exposed.

However, a password using prime numbers cannot be decrypted even if the encryption rules are known.

For example, a lock cannot be opened without a key, even if you know how to open it.

Likewise, a cryptographic system using prime numbers is a technology that provides each user with a unique 'key' by taking advantage of the unique property of prime numbers that large numbers are difficult to factor.

In this way, Hiroshi Oguri shows us how mathematics, which seems so distant from our daily lives, is actually close to our daily lives and a powerful tool for viewing the world, through examples of how mathematics has greatly changed our lives.

Why learn integration before differentiation?

Math becomes more friendly when you know why you're learning it.

The queen of all studies, mathematics.

Mathematics, which has been around since humans began to think, contains the essence of human intelligence spanning thousands of years.

From distributing crops and calculating interest to figuring out the size of the Earth, mathematics is closely tied to our daily lives.

But now, mathematics has become the subject we feel most distant and unfamiliar with.

Math books are full of symbols and shapes whose meanings are unclear, and what we do in math class is just mechanically solving problems according to formulas.

But mathematics is a tool and language that we absolutely need to survive in the 21st century.

Hiroshi Oguri, a world-renowned mathematical physicist and professor at the California Institute of Technology, wrote this book in the hope that his daughter would also experience the joy of mathematics.

It follows the concepts in math textbooks, sometimes adding interesting histories of mathematicians and sometimes adding stories from everyday life to make math more fun.

Why should we learn integration before differentiation? High school math textbooks typically explain differentiation first, then introduce integration as its inverse operation.

This order is intended to teach complete mathematics logically, but it is the opposite in terms of historical development.

Archimedes invented quadrature for integral calculations in the 3rd century BC, but Newton and Leibniz devised differential calculus in the 17th century.

This is because integration was a concept necessary for calculating visible quantities such as area or volume.

On the other hand, to understand differentiation, you must first understand the concept of limits.

Wouldn't it be easier to learn the intuitively easy-to-understand integral calculus before delving into the more difficult differential calculus? This book traces the history of mathematics, explaining intuitive concepts step by step, keeping readers engaged while also helping them gain a deeper understanding of the mathematical content.

The most powerful weapon I gave my daughter as she went out into the world: math.

We all remember the confusion we felt when we first learned math in school.

Unlike other subjects where everything is explained in words, in mathematics everything is compressed into symbols.

While learning negative numbers, fractions, and decimals beyond the numbers you can count on your fingers, and only mechanically performing addition and subtraction, some of you may have wondered how helpful this will be in real life.

This embarrassment becomes more severe as the grade level increases.

The seemingly meaningless symbols and figures, such as triangles and circles, exponents and logarithms, differentiation and integration, continue to increase.

I just solve problems mechanically, believing the teacher's words that it will help me someday.

But wouldn't understanding why mathematical concepts were created make math more approachable? For example, many people memorize that multiplying a negative number by a negative number results in a positive number, but don't understand why that happens.

This is because negative numbers are a concept that is difficult to think about in the first place.

Even renowned mathematicians had difficulty accepting negative numbers.

Even in the 17th century, the mathematical community was reluctant to accept negative numbers. Mathematician Blaise Pascal argued that "if you subtract 4 from 0, you get 0," and René Descartes also rejected negative numbers when solving equations, saying, "There is no number smaller than nothing."

The irrational numbers were even more difficult to accept.

It is said that Pythagoras killed Hippasus, who discovered irrational numbers in the ratio of the sides and diagonals of a square, by drowning him in the sea.

Although it is difficult to understand, negative numbers and irrational numbers are clearly numbers that exist in nature and are essential concepts for explaining natural phenomena.

Humanity has been able to use these numbers to create more powerful calculation methods.

Starting with natural numbers for simple calculations, we came up with zero and negative numbers to make subtraction easier, thought of fractions to make division easier, and discovered irrational numbers to construct shapes.

As the world of numbers expanded, our understanding of natural phenomena also deepened.

The discovery of the formula for solving quadratic equations allowed us to predict where a cannonball would land, and the introduction of logarithmic functions allowed us to calculate the Earth's orbital period, which led to Newton's law of gravitation.

Hiroshi Oguri says that explaining natural phenomena through mathematics is like finding a language that “can say things that could not be said and solve problems that could not be solved.”

Mathematics is a language created to accurately express things.

Mathematics is the most powerful tool a father has prepared for his daughter as she heads out into the world.

This book, with a heartfelt message to its daughter, emphasizes the importance of mathematics as a tool for living a meaningful life in the 21st century.

How to see the world through mathematics

Mathematics, which has been growing since ancient Greece, is everywhere in our daily lives.

Therefore, understanding mathematics is like acquiring a new language to read the world.

In Chapter 1, "Judging with Uncertain Information," Hiroshi Oguri calculates how much the odds of winning in gambling increase when the odds are slightly in your favor.

For example, if I have a 3% advantage over my opponent and continue to bet with enough money, my chances of doubling my stake go up to 99.75%.

In other words, in gambling, if you start with enough money when you have even the slightest advantage, you are almost certain to win. This fact can also be applied to how long we live.

For example, improving our daily habits, such as eating a balanced diet, exercising appropriately, and living a regular life, can significantly increase our chances of living a long life by giving us a 'slight advantage' in our chances of living a long life.

The power of mathematics is that it can clearly express in numbers how much this probability increases!

After all, mathematics is a discipline born out of necessity.

Since ancient times, wherever civilization developed, mathematics has always been present and has served as the foundation of civilization.

Mathematics, which may seem distant and unfamiliar, is actually directly connected to our lives.

For example, 'continued fractions', which are created by converting the denominator back into a fraction and then connecting unit fractions, have been used to make calendars.

If we assume that one year is approximately 365.24219 days and do a fractional approximation, 365.24219 is 365+0.024219≒365+1/4, so we can think of a calendar that has February 29th once every four years.

But in this case, there is an error of 0.00781 days.

Therefore, the Gregorian calendar we use today is a calendar created according to the rule that 'years divisible by 4 are leap years, but years divisible by 100 but not by 400 are not leap years.'

Even 'prime numbers', which seem to be the exclusive domain of mathematicians, are deeply rooted in our lives.

Prime numbers, also called the 'atoms of numbers' because they hold the secrets of numbers, are a concept that has fascinated mathematicians from ancient Greece to the present day.

Mathematicians are studying the patterns of appearance of prime numbers and methods for determining prime numbers, but there are still many unsolved problems related to prime numbers.

Nevertheless, minorities are used urgently in our lives.

The encryption system used for shopping or making payments on the Internet was developed by applying the properties of prime numbers.

Until now, no matter how complex the encryption technology was, it could be quickly broken once the rules of the encryption were exposed.

However, a password using prime numbers cannot be decrypted even if the encryption rules are known.

For example, a lock cannot be opened without a key, even if you know how to open it.

Likewise, a cryptographic system using prime numbers is a technology that provides each user with a unique 'key' by taking advantage of the unique property of prime numbers that large numbers are difficult to factor.

In this way, Hiroshi Oguri shows us how mathematics, which seems so distant from our daily lives, is actually close to our daily lives and a powerful tool for viewing the world, through examples of how mathematics has greatly changed our lives.

Why learn integration before differentiation?

Math becomes more friendly when you know why you're learning it.

The queen of all studies, mathematics.

Mathematics, which has been around since humans began to think, contains the essence of human intelligence spanning thousands of years.

From distributing crops and calculating interest to figuring out the size of the Earth, mathematics is closely tied to our daily lives.

But now, mathematics has become the subject we feel most distant and unfamiliar with.

Math books are full of symbols and shapes whose meanings are unclear, and what we do in math class is just mechanically solving problems according to formulas.

But mathematics is a tool and language that we absolutely need to survive in the 21st century.

Hiroshi Oguri, a world-renowned mathematical physicist and professor at the California Institute of Technology, wrote this book in the hope that his daughter would also experience the joy of mathematics.

It follows the concepts in math textbooks, sometimes adding interesting histories of mathematicians and sometimes adding stories from everyday life to make math more fun.

Why should we learn integration before differentiation? High school math textbooks typically explain differentiation first, then introduce integration as its inverse operation.

This order is intended to teach complete mathematics logically, but it is the opposite in terms of historical development.

Archimedes invented quadrature for integral calculations in the 3rd century BC, but Newton and Leibniz devised differential calculus in the 17th century.

This is because integration was a concept necessary for calculating visible quantities such as area or volume.

On the other hand, to understand differentiation, you must first understand the concept of limits.

Wouldn't it be easier to learn the intuitively easy-to-understand integral calculus before delving into the more difficult differential calculus? This book traces the history of mathematics, explaining intuitive concepts step by step, keeping readers engaged while also helping them gain a deeper understanding of the mathematical content.

The most powerful weapon I gave my daughter as she went out into the world: math.

We all remember the confusion we felt when we first learned math in school.

Unlike other subjects where everything is explained in words, in mathematics everything is compressed into symbols.

While learning negative numbers, fractions, and decimals beyond the numbers you can count on your fingers, and only mechanically performing addition and subtraction, some of you may have wondered how helpful this will be in real life.

This embarrassment becomes more severe as the grade level increases.

The seemingly meaningless symbols and figures, such as triangles and circles, exponents and logarithms, differentiation and integration, continue to increase.

I just solve problems mechanically, believing the teacher's words that it will help me someday.

But wouldn't understanding why mathematical concepts were created make math more approachable? For example, many people memorize that multiplying a negative number by a negative number results in a positive number, but don't understand why that happens.

This is because negative numbers are a concept that is difficult to think about in the first place.

Even renowned mathematicians had difficulty accepting negative numbers.

Even in the 17th century, the mathematical community was reluctant to accept negative numbers. Mathematician Blaise Pascal argued that "if you subtract 4 from 0, you get 0," and René Descartes also rejected negative numbers when solving equations, saying, "There is no number smaller than nothing."

The irrational numbers were even more difficult to accept.

It is said that Pythagoras killed Hippasus, who discovered irrational numbers in the ratio of the sides and diagonals of a square, by drowning him in the sea.

Although it is difficult to understand, negative numbers and irrational numbers are clearly numbers that exist in nature and are essential concepts for explaining natural phenomena.

Humanity has been able to use these numbers to create more powerful calculation methods.

Starting with natural numbers for simple calculations, we came up with zero and negative numbers to make subtraction easier, thought of fractions to make division easier, and discovered irrational numbers to construct shapes.

As the world of numbers expanded, our understanding of natural phenomena also deepened.

The discovery of the formula for solving quadratic equations allowed us to predict where a cannonball would land, and the introduction of logarithmic functions allowed us to calculate the Earth's orbital period, which led to Newton's law of gravitation.

Hiroshi Oguri says that explaining natural phenomena through mathematics is like finding a language that “can say things that could not be said and solve problems that could not be solved.”

Mathematics is a language created to accurately express things.

Mathematics is the most powerful tool a father has prepared for his daughter as she heads out into the world.

This book, with a heartfelt message to its daughter, emphasizes the importance of mathematics as a tool for living a meaningful life in the 21st century.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 25, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 340 pages | 504g | 152*223*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791166893100

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)