The very deep history of our humankind

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

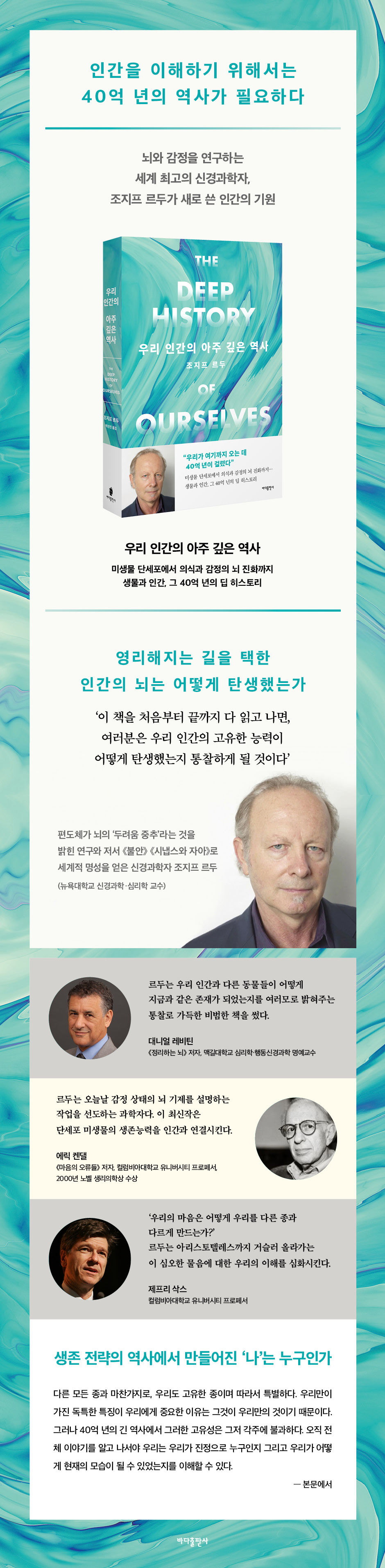

Understanding Humanity Through 4 Billion Years of EvolutionHow did we humans become what we are today? Joseph LeDoux, a world-renowned neuroscientist specializing in the study of the brain and emotions, explores the human brain and behavior across four billion years of evolution to find out.

Beyond a human-centric perspective, we gain insight into our own profound history through our connections with diverse living beings.

May 11, 2021. Natural Science PD Kim Tae-hee

To understand humans

4 billion years of history are needed

“Who am I?” “How are humans similar and different from other animals?” “Are emotions created?” A world-renowned neuroscientist has begun to answer these profound questions that humanity has explored for thousands of years.

Joseph LeDoux, a leading figure in the study of the brain, consciousness, emotion, and behavior, suddenly turns his attention to the distant past, to the era of bacteria 4 billion years ago.

Because every living being today is connected in some way to all living beings of the past and present.

As we delve deeper into the microbial life of the primitive Earth and its scientific reality, paradoxically, we come face to face with the roots of human nature.

Tracing back to the common ancestor of all life, we ponder the learning and memory abilities inherited from our bacterial ancestors billions of years ago.

A long, pre-human history, unwritten in language, 『The Very Deep History of Humans』 goes beyond brain science, psychology, and big history, which have so far focused on humans, and places humans in a corner of the history of life on Earth, not at the center.

We humans are no different from countless species that have disappeared in the history of evolution, but it makes us deeply aware of our own unique selves.

4 billion years of history are needed

“Who am I?” “How are humans similar and different from other animals?” “Are emotions created?” A world-renowned neuroscientist has begun to answer these profound questions that humanity has explored for thousands of years.

Joseph LeDoux, a leading figure in the study of the brain, consciousness, emotion, and behavior, suddenly turns his attention to the distant past, to the era of bacteria 4 billion years ago.

Because every living being today is connected in some way to all living beings of the past and present.

As we delve deeper into the microbial life of the primitive Earth and its scientific reality, paradoxically, we come face to face with the roots of human nature.

Tracing back to the common ancestor of all life, we ponder the learning and memory abilities inherited from our bacterial ancestors billions of years ago.

A long, pre-human history, unwritten in language, 『The Very Deep History of Humans』 goes beyond brain science, psychology, and big history, which have so far focused on humans, and places humans in a corner of the history of life on Earth, not at the center.

We humans are no different from countless species that have disappeared in the history of evolution, but it makes us deeply aware of our own unique selves.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

Prologue: Why did I write this book?

Part 1 Our Place in the Natural World

Chapter 1 Deep Roots

Chapter 2 The Tree of Life

Chapter 3: The Beginning of Nature

Chapter 4 Common Ancestors

Chapter 5: Being Alive

Part 2: Survival and Behavior

Chapter 6: Organismal Behavior

Chapter 7: Can only animals act?

Chapter 8 The First Survivor

Chapter 9: Strategies and Tactics for Survival

Chapter 10: Rethinking Your Behavior

Part 3: The Life of Microorganisms

Chapter 11 In the Beginning

Chapter 12 Life Itself

Chapter 13: Survival Machines

Chapter 14: The Birth of Cell Organelles

Chapter 15: The Marriage of Luca's Descendants

Chapter 16: Breathing New Life into Old Things

Part 4: The Transition to Complexity

Chapter 17 Size Matters

Chapter 18: The Sexual Revolution

Chapter 19: Mitochondrial Eve, Jesse James, and the Origin of Sex

Chapter 20: The Age of Colonies

Chapter 21: The Two-Step Selection Process

Chapter 22: Swimming through a narrow gate with a flagellum

Part 5… …and animals invented neurons

Chapter 23 What are animals?

Chapter 24: A Humble Beginning

Chapter 25: Animals Take Form

Chapter 26: The Magic of Neurons

Chapter 27: How Neurons and the Nervous System Arise

Part 6: Traces of Metazoans in the Sea

Chapter 28: Looking straight ahead

Chapter 29: Organizational Problems

Chapter 30: Oral or Anal?

Chapter 31: Deep-sea Deuterostomes Connect Us to the Past

Chapter 32: The Tale of the Two Claws

Part 7: The Arrival of Vertebrates

Chapter 33: The Bow Plan of Vertebrates

Chapter 34: Life at Sea

Chapter 35 On Land

Chapter 36 Along the Milky Way

Part 8: Ladders and Trees to the Vertebrate Brain

Chapter 37: The Vertebrate Nerves - Bauplan

Chapter 38: Ludwig's Ladder

Chapter 39: The Temptation of the Trinity

Chapter 40: Darwin's Confusing Psychology of Emotions

Chapter 41: How Basic Are Basic Emotions?

Part 9: The Beginning of Cognition

Chapter 42 Cognitive Abilities

Chapter 43: Finding Cognition in the Behaviorist Zone

Chapter 44: The Evolution of Behavioral Flexibility

Part 10: Surviving and Thriving Through Thought

Chapter 45: Careful Reflection

Chapter 46: The Deliberative Cognitive Engine

Chapter 47: Chatting

Part 11: The Hardware of Cognition

Chapter 48: Perception and Memory Sharing Circuits

Chapter 49 Cognitive Association

Chapter 50: Overheating after Rewiring

Part 12 Subjectivity

Chapter 51: Three Clues to Consciousness

Chapter 52: What is it like to be conscious?

Chapter 53: Let's go into more detail.

Chapter 54 Higher-Order Cognition in the Brain

Part 13: Consciousness Through the Lens of Memory

Chapter 55: The Invention of Experience

Chapter 56: Memory, Consciousness, and Self-Awareness

Chapter 57: Putting Memories Back in Place

Chapter 58: Higher Cognition Through the Lens of Memory

Part 14: Shallow Places

Chapter 59: The Difficult Problem of Other Minds

Chapter 60: Sneaking into Consciousness

Chapter 61 Types of Mind

Part 15: Emotional Subjectivity

Chapter 62: The Steep Slope of Emotional Semantics

Chapter 63: Can Survival Circuits Save Us From Trouble?

Chapter 64 Thoughtful Feelings

Chapter 65: The Feeling Brain Ignites

Chapter 66: Survival is Deep, but Emotions are Shallow

Epilogue: Can we overcome self-consciousness and survive?

Appendix: Timeline of the History of Life

Illustration Credit

References

Search

Prologue: Why did I write this book?

Part 1 Our Place in the Natural World

Chapter 1 Deep Roots

Chapter 2 The Tree of Life

Chapter 3: The Beginning of Nature

Chapter 4 Common Ancestors

Chapter 5: Being Alive

Part 2: Survival and Behavior

Chapter 6: Organismal Behavior

Chapter 7: Can only animals act?

Chapter 8 The First Survivor

Chapter 9: Strategies and Tactics for Survival

Chapter 10: Rethinking Your Behavior

Part 3: The Life of Microorganisms

Chapter 11 In the Beginning

Chapter 12 Life Itself

Chapter 13: Survival Machines

Chapter 14: The Birth of Cell Organelles

Chapter 15: The Marriage of Luca's Descendants

Chapter 16: Breathing New Life into Old Things

Part 4: The Transition to Complexity

Chapter 17 Size Matters

Chapter 18: The Sexual Revolution

Chapter 19: Mitochondrial Eve, Jesse James, and the Origin of Sex

Chapter 20: The Age of Colonies

Chapter 21: The Two-Step Selection Process

Chapter 22: Swimming through a narrow gate with a flagellum

Part 5… …and animals invented neurons

Chapter 23 What are animals?

Chapter 24: A Humble Beginning

Chapter 25: Animals Take Form

Chapter 26: The Magic of Neurons

Chapter 27: How Neurons and the Nervous System Arise

Part 6: Traces of Metazoans in the Sea

Chapter 28: Looking straight ahead

Chapter 29: Organizational Problems

Chapter 30: Oral or Anal?

Chapter 31: Deep-sea Deuterostomes Connect Us to the Past

Chapter 32: The Tale of the Two Claws

Part 7: The Arrival of Vertebrates

Chapter 33: The Bow Plan of Vertebrates

Chapter 34: Life at Sea

Chapter 35 On Land

Chapter 36 Along the Milky Way

Part 8: Ladders and Trees to the Vertebrate Brain

Chapter 37: The Vertebrate Nerves - Bauplan

Chapter 38: Ludwig's Ladder

Chapter 39: The Temptation of the Trinity

Chapter 40: Darwin's Confusing Psychology of Emotions

Chapter 41: How Basic Are Basic Emotions?

Part 9: The Beginning of Cognition

Chapter 42 Cognitive Abilities

Chapter 43: Finding Cognition in the Behaviorist Zone

Chapter 44: The Evolution of Behavioral Flexibility

Part 10: Surviving and Thriving Through Thought

Chapter 45: Careful Reflection

Chapter 46: The Deliberative Cognitive Engine

Chapter 47: Chatting

Part 11: The Hardware of Cognition

Chapter 48: Perception and Memory Sharing Circuits

Chapter 49 Cognitive Association

Chapter 50: Overheating after Rewiring

Part 12 Subjectivity

Chapter 51: Three Clues to Consciousness

Chapter 52: What is it like to be conscious?

Chapter 53: Let's go into more detail.

Chapter 54 Higher-Order Cognition in the Brain

Part 13: Consciousness Through the Lens of Memory

Chapter 55: The Invention of Experience

Chapter 56: Memory, Consciousness, and Self-Awareness

Chapter 57: Putting Memories Back in Place

Chapter 58: Higher Cognition Through the Lens of Memory

Part 14: Shallow Places

Chapter 59: The Difficult Problem of Other Minds

Chapter 60: Sneaking into Consciousness

Chapter 61 Types of Mind

Part 15: Emotional Subjectivity

Chapter 62: The Steep Slope of Emotional Semantics

Chapter 63: Can Survival Circuits Save Us From Trouble?

Chapter 64 Thoughtful Feelings

Chapter 65: The Feeling Brain Ignites

Chapter 66: Survival is Deep, but Emotions are Shallow

Epilogue: Can we overcome self-consciousness and survive?

Appendix: Timeline of the History of Life

Illustration Credit

References

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

By the time you finish this book, you'll have climbed the tree of life, gaining insight into how our unique abilities—thinking, feeling, and so on—have evolved from the survival skills of primitive microorganisms, allowing us to survive and thrive. You'll be forced to seriously consider not only your own past and future, but also the future of our species.

--- p.14

When animals detect predators, freeze or flee, eat, drink, and mate to defend themselves, manage energy, balance body fluids, and reproduce, scientists and laypeople alike tend to explain these activities as expressions of underlying psychological states—conscious sensory experiences such as fear, hunger, thirst, and sexual pleasure.

In effect, we are projecting our own experiences onto other organisms.

Given how ancient these behaviors are, and how they arose long before the development of nervous systems, we should be more cautious about judging the behavior of other animals based on our own mental states.

--- p.22

“We are our brains.” Some may consider this statement an indisputable fact, while others may find it preposterous.

What is clear is that the most fundamental element that determines who each of us is lies in our brain.

Because we have a brain, we can think, feel joy and sorrow, communicate through language, reflect on moments in our lives, and predict, plan, and contemplate the future in our imagination.

--- p.28

We often think of actions as tools of the mind, but that is not the case.

Of course, human behavior also reflects the intentions, desires, and fears of the conscious mind.

But if we delve deeply into the history of behavior, we cannot help but conclude that behavior is the first and foremost tool for survival, whether in single-celled organisms or in complex organisms capable of conscious control of some behaviors.

Linking behavior to mental activity, as if mental activity itself were something else, is merely an evolutionary post-hoc explanation.

--- p.31

Actions are not created for the subjective mind.

It arises and persists to increase fitness - to ensure that organisms survive until they reach a reproductive age.

From this perspective, the behavior of all organisms, from humans to bacteria, is on an equal footing.

Consciousness, in the very sense we use it in our daily lives, has played a minor role throughout the history of life.

If we assume that most behaviors have arisen through unconscious systems over a long evolutionary process (a very reasonable assumption), then we should assume that such behaviors, even human behaviors, are under unconscious control unless proven otherwise.

And that's when the science of behavior will progress much more smoothly.

The same goes for the science of consciousness.

--- pp.80~81

Differences play a crucial role in defining species, but in the vast horizon of life, differences alone do not make one thing more valuable than another.

We may think that the type of life we lead is better than another, but ultimately, nothing but survival is the measure by which we judge a life.

There is no scale that can tell us whether our type of life is better or worse than that of apes, monkeys, cats, rats, birds, snakes, frogs, fish, worms, jellyfish, sponges, flagellates, fungi, plants, archaea, or bacteria.

If the measure of longevity is paper, we can never be better than primitive single-celled organisms.

--- p.343

Our conscious mind is full of pride.

We believe that all our psychological behavior comes from our mind.

But we are more like drivers behind the wheel of self-driving cars.

We can take control when necessary, but the rest of the time we can consciously think about other things.

--- pp.359~361

Perhaps we will never know whether other animals have conscious experiences, and if so, whether their experiences are like ours.

Because it is difficult to scientifically measure animal consciousness.

But in some sense, this issue is not so important in interspecies comparisons.

We should focus more on the cognitive and behavioral abilities that animals can measurably share with us, rather than on consciousness itself.

Some of these abilities, even if they did not give other animals the same consciousness we have, certainly contributed to the evolution of consciousness in humans.

--- pp.433~434

We are connected to the survival history of organisms with nervous systems through our survival circuits.

In other words, the human species, as part of the history of life, also has universal survival strategies implemented by survival circuits and behaviors.

By separating the history of emotions and other conscious states from the deep history of survival circuits, we can determine our place in the overall history of life.

--- p.14

When animals detect predators, freeze or flee, eat, drink, and mate to defend themselves, manage energy, balance body fluids, and reproduce, scientists and laypeople alike tend to explain these activities as expressions of underlying psychological states—conscious sensory experiences such as fear, hunger, thirst, and sexual pleasure.

In effect, we are projecting our own experiences onto other organisms.

Given how ancient these behaviors are, and how they arose long before the development of nervous systems, we should be more cautious about judging the behavior of other animals based on our own mental states.

--- p.22

“We are our brains.” Some may consider this statement an indisputable fact, while others may find it preposterous.

What is clear is that the most fundamental element that determines who each of us is lies in our brain.

Because we have a brain, we can think, feel joy and sorrow, communicate through language, reflect on moments in our lives, and predict, plan, and contemplate the future in our imagination.

--- p.28

We often think of actions as tools of the mind, but that is not the case.

Of course, human behavior also reflects the intentions, desires, and fears of the conscious mind.

But if we delve deeply into the history of behavior, we cannot help but conclude that behavior is the first and foremost tool for survival, whether in single-celled organisms or in complex organisms capable of conscious control of some behaviors.

Linking behavior to mental activity, as if mental activity itself were something else, is merely an evolutionary post-hoc explanation.

--- p.31

Actions are not created for the subjective mind.

It arises and persists to increase fitness - to ensure that organisms survive until they reach a reproductive age.

From this perspective, the behavior of all organisms, from humans to bacteria, is on an equal footing.

Consciousness, in the very sense we use it in our daily lives, has played a minor role throughout the history of life.

If we assume that most behaviors have arisen through unconscious systems over a long evolutionary process (a very reasonable assumption), then we should assume that such behaviors, even human behaviors, are under unconscious control unless proven otherwise.

And that's when the science of behavior will progress much more smoothly.

The same goes for the science of consciousness.

--- pp.80~81

Differences play a crucial role in defining species, but in the vast horizon of life, differences alone do not make one thing more valuable than another.

We may think that the type of life we lead is better than another, but ultimately, nothing but survival is the measure by which we judge a life.

There is no scale that can tell us whether our type of life is better or worse than that of apes, monkeys, cats, rats, birds, snakes, frogs, fish, worms, jellyfish, sponges, flagellates, fungi, plants, archaea, or bacteria.

If the measure of longevity is paper, we can never be better than primitive single-celled organisms.

--- p.343

Our conscious mind is full of pride.

We believe that all our psychological behavior comes from our mind.

But we are more like drivers behind the wheel of self-driving cars.

We can take control when necessary, but the rest of the time we can consciously think about other things.

--- pp.359~361

Perhaps we will never know whether other animals have conscious experiences, and if so, whether their experiences are like ours.

Because it is difficult to scientifically measure animal consciousness.

But in some sense, this issue is not so important in interspecies comparisons.

We should focus more on the cognitive and behavioral abilities that animals can measurably share with us, rather than on consciousness itself.

Some of these abilities, even if they did not give other animals the same consciousness we have, certainly contributed to the evolution of consciousness in humans.

--- pp.433~434

We are connected to the survival history of organisms with nervous systems through our survival circuits.

In other words, the human species, as part of the history of life, also has universal survival strategies implemented by survival circuits and behaviors.

By separating the history of emotions and other conscious states from the deep history of survival circuits, we can determine our place in the overall history of life.

--- pp.480~481

Publisher's Review

"How does our mind make us different from other species?"

Le Dou dates back to Aristotle.

"It deepens our understanding of this profound question."

Jeffrey Sachs (University Professor, Columbia University)

I chose the path to becoming smarter

How the human brain was born

Where do we stand in the natural world? In the primordial oceans of Earth, the primordial forms of life, the protocells, were created, and these biological events, layer upon layer, gave birth to us today.

This book confronts the deep history of life, a vast drama spanning four billion years, to understand ourselves as products of evolution.

All of our human actions today are connected to the history of evolution.

In the prologue, Joseph LeDoux, the author of this book and a world-renowned neuroscientist who discovered that the amygdala is the brain's fear center, explains why we need to know this long and arduous time.

“If you really want to understand human nature, you have to understand its evolutionary history.” (p. 17) Unique characteristics that were constantly added to organisms over a very long evolutionary process ultimately gave birth to us and our brains as we are today.

This characteristic can only be known by examining the natural history of life on Earth (see page 32). The more we can understand ourselves, the more clearly we can determine which parts of ourselves are related to what we inherited from various organisms.

This book explores the human brain and behavior across four billion years of evolutionary history.

While there have been many attempts to understand human nature through comparisons with closely related species such as primates and mammals, few books, like this one, trace back the origins of life, all the way to single-celled microorganisms, and examine the position of humans within the entire history of life.

Each chapter of the book is a concise 'one-topic' filled with short, concise reflections and insights.

If you want to know more specifically about a particular topic, you can read only the parts related to the topic of interest.

(For example, how did life begin, when did bacteria start behaving, how did sexual reproduction emerge, what process led to the emergence of multicellular organisms from single-celled organisms, how did the nervous system evolve, how did cognition and emotion evolve, what do we know about consciousness and the brain, etc.) After reading this book, you will gain insight into how our own unique abilities, such as thinking and emotion, that have allowed us to survive and thrive could have emerged from the survival skills of primitive microorganisms, and you will be forced to seriously consider not only your own past and future, but also the future of our species.

This book, LeDoux's fourth, deals with the issues of the 'brain', 'emotions', and 'consciousness' like his previous works (The Feeling Brain, Synapses and the Self, and Anxiety), but it unfolds the story on the bigger picture of 'evolution' and 'behavior'.

This is the ultimate question that Le Dou seeks to answer by weaving together five of the most fascinating topics in current science.

How did our brains shape us into the human beings we are today, capable of reasoning and reasoning, language and culture, and self-awareness?

We were born billions of years ago by single-celled microorganisms.

Inherited learning and memory abilities

While LeDoux acknowledges survival behaviors that date back to bacteria as universal traits shared by all organisms, he considers consciousness and emotions, which emerged in the human brain only very recently (only a few million years ago), to be uniquely human abilities.

Ledoux, struck by a fellow scientist's research showing that genes related to synaptic plasticity were similar in rodents, sea slugs, and even single-celled protozoans like paramecia and amoebas, decided to go back to the origins of life and see how we are similar to and different from other organisms.

'Behavior', which began simultaneously with the history of life, is a primary tool for survival, and all organisms exhibit several common survival behaviors.

The task is to avoid danger, obtain nutrients, maintain water and body temperature, and reproduce.

These primitive survival strategies of defense, energy management, fluid balance, and reproduction can also be found in bacteria that appeared on Earth 3.5 billion years ago as descendants of the 'most recent common ancestor of all life on Earth (LUCA)'.

Bacteria exhibit 'tactic behavior', using their ability to sense chemicals or light and their ability to move, to approach beneficial substances and flee from harmful substances.

It also regulates the concentration of water and electrolytes within the cell to prevent cell collapse, and regulates internal temperature by reorganizing biochemical processes to suit the external temperature.

And through cell division (asexual reproduction), they continue to thrive as the most numerous organism on Earth to this day.

What's even more surprising is that bacteria and their descendants, the single-celled protozoa, can acquire and store information about environmental conditions and then use it to respond more appropriately to environmental changes.

In other words, they also have the ability to learn and remember.

LeDoux defines memory as "a cellular function that facilitates survival by allowing us to obtain information from past experiences," adding that the nervous system is not necessarily required for learning and memory.

These solutions discovered by the first single-celled microorganisms for survival were successfully passed on to all organisms that appeared afterward, and have continued to lead to the complex survival behaviors of complex organisms, including humans.

What LeDoux is trying to say with 'survival behavior' is not that all organisms on Earth are biologically interconnected, but rather that "the roots of our everyday, routine behaviors are much older than we usually realize," and that "simple cells are also engaged in sophisticated survival activities, and these primitive survival activities continue in our lives today."

Humans and animals use it every day

The origin of cells called neurons

The first half of the book traces how these survival strategies were developed by primitive single-celled organisms, preserved by primitive multicellular organisms, and then, after the nervous system developed in early invertebrates, taken over by specialized cells called neurons, and later used daily by all animals, including humans.

In the process, we come to understand much more easily in the context of the overall evolution many interesting facts about life that we had previously known in fragments but did not know in detail.

Representative hypotheses include the story of how eukaryotes, in which a nucleus and mitochondria coexist, arose from archaea and the bacteria they consumed (endosymbiosis); the two-stage natural selection that unicellular organisms must go through in order for them to become multicellular organisms (first, the constituent cells must have similar genetic characteristics [fitness sorting], and second, a division of labor must occur in which the needs of the organism are prioritized over the needs of the cells [fitness delegation]); and the process by which neurons and the nervous system first appeared in cnidarians (such as hydra and jellyfish) (the sensory and motor cells of sponge larvae grew together and some of the sensory cells became long, and eventually these became the axons of neurons that communicate with electrical signals over long distances and transmit information with chemicals over short distances).

Finally, it reaches the human brain, correcting the classic errors that still have an impact today.

These are Ludwig Edinger's 'sequential formation theory' and Paul McLean's 'three-brain theory'.

The sequential formation theory claims that the human brain was structured as it is today by stacking layers of reptilian brain (basal ganglia), early mammalian brain (paleocortex), and mammalian brain (neocortex).

This theory, which is based on the idea that the human brain represents the pinnacle of evolution, has been refuted by numerous lines of evidence, including the discovery of homologous structures to the neocortex in reptiles and birds.

MacLean faithfully followed Edinger's theory and added explanations for the functions of each area, arguing that the basal ganglia were responsible for instincts, the palpebral cortex (which MacLean called the "limbic system") for emotions, and the neocortex for cognitive abilities.

However, the three-brain theory not only has all of Edinger's anatomical problems, but also has an incorrect explanation of brain function. The paleocortex (hippocampus and cingulate cortex) has been shown to contribute to cognitive activities such as memory, and the neocortex has also been shown to be involved in emotional experiences.

It is not present in the brains of other primates.

The prefrontal cortex, a unique part of the human brain responsible for deliberative cognition

We humans have been able to thrive by choosing to become smarter rather than bigger or more agile.

Cognition is a product of biological processes made possible by the nervous system, and it has been proven through numerous experiments that it varies from organism to organism.

Bacteria, protozoa, and cnidarians only have Pavlovian simple associations (they approach a light when it is close to food), while protozoa, fish, amphibians, and reptiles only have Pavlovian cognition (if they feel nauseated after eating food, they avoid that food thereafter), and mammals and birds have goal-directed instrumental cognition (if they press the lever while the light is flashing, they get food).

But only humans are capable of conscious deliberation (problem solving through memory, reasoning, and prediction, not trial and error).

The second half of the book examines the functional roles of each region of the human brain and how their networks influence perception, memory, cognition, and emotion—our conscious experiences.

Le Dou focuses on the prefrontal cortex, and particularly the 'frontal pole', as the core area of consciousness.

The prefrontal cortex is a unique region of the human brain, not found in other primates. It is where our most abstract conceptual representations are created and processed, and is responsible for deliberative cognition such as long-term goals, future planning, hierarchical relationship reasoning, and problem solving.

The frontal pole is also related to self-awareness, that is, self-consciousness.

It is all thanks to self-awareness that we can distinguish ourselves from others and understand the minds of others, and this is an ability that only humans possess.

In the history of survival strategies

The human emotions and mind that are created

We feel fear when we react to danger.

Because these two experiences often occur together, we think that fear is what causes such a response.

But according to Le Dou, this is not true.

The brain systems that control survival behavior and the brain systems that govern the conscious feelings (emotions) experienced when performing those behaviors are separate from each other.

“Actions and feelings occur simultaneously, not because feelings cause actions, but because each system responds to the same stimulus.” Although actions are often thought of as tools of the mind, mental activities such as the mind arose much later in evolutionary history.

Linking behavior and mental activity is merely an 'evolutionary post-hoc explanation'.

Instead of the confusing expression 'fear circuit' that seems to cause mental states to cause behavior, LeDoux introduced the term 'survival circuit', arguing that behavior follows the mechanism of 'survival stimulus - survival circuit - survival response', but emotions (feelings) are processed separately in the cortical cognitive circuit (higher-order prefrontal network).

For example, when the sensory system receives information about a danger such as a snake underfoot, the defensive survival state (defensive survival circuit) is activated in the amygdala, causing behavioral responses (freezing, avoidance) and physiological responses (trembling, cold sweat), and at the same time, inducing feelings (fear, anxiety) in the cortical cognitive circuit.

According to LeDoux's multistate hierarchical model, conscious fear arises from cognitively interpreting a situation as dangerous.

In other words, it is not the amygdala that causes fear, but rather our individual fear schemas (our knowledge of danger acquired throughout our lives), and fear is not universal, but always frightening 'to me.'

Emotions are self-aware consciousness, and “without self, there are no emotions.”

This fact explains why many pharmaceutical companies have so far failed to develop drugs that reduce fear and anxiety.

Most drugs are developed by measuring behavioral changes in animals, but this only affects survival circuits and not the cortical cognitive circuits that actually cause fear and anxiety.

In animal consciousness and human consciousness

Similarities and Differences

If emotions are created in the above way, then since only humans can experience self-aware consciousness, we can say that emotions also arise only in humans.

At first glance, this sounds like depriving other species, especially animals close to humans, of consciousness and emotions.

However, Le Dou does not deny that animals have conscious experiences.

However, I believe that it is possible that animals' conscious experiences are quite different from those of humans, and that it would be extremely difficult to scientifically confirm this without language.

If we accept this fact, we should be more cautious when saying that other animals have conscious experiences similar to humans.

Since Darwin argued that animals also have emotions, citing similarities in human and animal behavior, the tendency toward 'anthropocentrism' and 'anthropomorphism' has been deeply rooted in academia.

When we assume that other animals experience certain conscious experiences (feeling fear, hunger, thirst, sexual pleasure) just because we experience them during our survival behaviors (defense, energy management, fluid balance, reproduction), we are simply projecting our own experiences onto other organisms.

Contrary to the claims of anthropomorphism advocates like Frans de Waal, Jane Goodall, and Marc Bekoff (“If closely related species exhibit the same behavior, then the underlying mental processes are probably the same”), observation of behavior alone does not link behavior to consciousness.

This is because behavior is not only controlled consciously, but also unconsciously.

Unfortunately, however, current animal research is preoccupied with “accumulating evidence to support the intuition that consciousness is involved,” rather than determining whether specific behaviors are controlled consciously or unconsciously.

Anthropomorphic thinking may have been hardwired into our genes by natural selection because it was useful for predicting and controlling the behavior of other animals.

But just because it is human nature and natural doesn't mean it is scientifically correct.

Science must be based on actual facts, not intuition.

Humans are not the pinnacle of evolution.

The uniquely human self-aware consciousness that created and destroyed civilization

LeDoux argues that emotions are a refractive adaptation of language and self-awareness (traits that arose as a byproduct of other traits but were naturally selected for their utility), and that the ability to personalize values (“How dangerous is this 'to me'?”) was selected for because it was more effective for survival than the unconscious survival behavior of simply detecting and avoiding danger.

Just because LeDoux identifies emotions and consciousness as uniquely human characteristics, he doesn't mean he regards humans as the pinnacle of evolution. ("In the long history of four billion years, such uniqueness is merely a footnote.") Rather, in the epilogue, LeDoux highlights the negative aspects of self-aware consciousness.

Self-awareness has brought about great achievements, including today's science, technology, and culture and art, but on the other hand, it has also made possible mental traits such as distrust, hatred, greed, and selfishness, "which could destroy our species." LeDoux warns of a dark future brought about by ecological destruction, including climate change and mass extinction, and urges a conscious awakening to rapid cognitive and cultural evolution instead of slow biological evolution, that is, to our way of life in which we live together with other species.

“LeDoux is a leading scientist leading the important work today to explain the brain mechanisms of emotional states.

In this latest work, LeDoux seeks to link the survival abilities of single-celled microorganisms to our unique ability to survive.

This human capacity is profoundly influenced by our ability to think and feel, to contemplate our own past and future, as well as that of humanity.

“It is a wonderful book, and, as Le Dou says, truly ‘our own deep history.’”

--Eric Kandel (author of "Faults of the Mind," University Professor, Columbia University, 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine)

“LeDoux’s new book begins with the biology of simple organisms and ends with a rigorously argued argument for viewing human emotions and consciousness as higher-order cognitive processes at the peak of biological complexity.

Even those who don't entirely agree with his views (though I do agree with many of them), cannot help but appreciate and celebrate his accomplishments.”

--Antonio Damasio, author of "The Evolution of Feelings" and professor of neuroscience at the University of Southern California

“LeDoux has written an extraordinary book, full of insights that illuminate many aspects of how we humans and other animals came to be what we are today.

“It is a very readable book for the general public, and is full of useful information for other neuroscientists as well.”

Daniel Levitin, author of The Organized Brain and Professor Emeritus of Psychology and Behavioral Neuroscience, McGill University

“‘How does our mind make us different from other species?’ Ledoux deepens our understanding of this profound question, which dates back to Aristotle.

There is no better guide than Le Dou.

LeDoux is one of the world's leading neuroscientists, working at the forefront of behavior, emotion, and consciousness.

Ledoux cleverly and wittily traces the 4 billion-year history of life, showing how humans, while sharing basic behaviors with single-celled organisms, have made the leap to reflective self-awareness, the only species in the universe to do so.

“It was so interesting and exciting to read.”

--Jeffrey Sachs (University Professor, Columbia University)

“A very entertaining and informative journey covering the origins of life and the emergence of creatures with complex mental lives.

A vital perspective on how we humans came to have intelligence, consciousness, and emotions.

“From biology to psychology, everything is a masterpiece.”

--Susan Schneider (NASA/Library of Congress Astrobiology Researcher)

“LeDoux presents his own remarkable synthesis of zoology, neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy.

His central themes are the emergence of consciousness through the evolution of the nervous system, the behaviors it controls, and the Tree of Consciousness, not the Tree of Life, where consciousness leads us.

“A wonderful book that broadens your mind.”

--Trevor Robbins (Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, University of Cambridge)

“A fascinating book that shows the grand evolution of life, from molecules to consciousness.

“LeDoux offers a fresh look at core ideas in this field, including exciting new insights into how our brains work.”

--Marion Dawkins (Professor of Animal Behavior, Oxford University)

“Le Dou is a rare scientist who sees both the trees and the forest.

This incredibly easy-to-read book will appeal to a wide range of readers.

An introduction to the evolution of life is combined with a discussion of psychological processes that need to be illuminated.

The discussion is sophisticated, historically informed, and provocative.

“An original work by a renowned scientist who understands the brain and its relationship to psychological events.”

--Jerome Kagan (Professor Emeritus of Psychology, Harvard University)

“The most important thing to know about consciousness is that it evolved.

In this masterpiece, LeDoux reveals not only the overall picture of that evolution, but also crucial details of the complex nervous system that allowed consciousness to emerge in humans.”

--Christopher Frith (psychologist, professor emeritus, University College London)

“It’s always wise to try to understand the context.

Placing ourselves within the context of 4 billion years of history is a brilliant way to change perspective.

Short but interesting articles ask:

“What is consciousness?” “What are emotions?” And most of all, “Who am I?” The answers will surprise you.”

--Hazel Rose Marcus, cultural psychologist and professor of behavioral sciences at Stanford University

“This book shows the continuity of how biological processes produce behavior, from the simplest to the most complex organisms.

The book supports the argument that the processes that drive the behavior of complex organisms like us and those that lead to conscious awareness are quite different.

Le Dou presents all this with masterful knowledge of the big picture and fascinating detail, concluding with his own theory of consciousness and emotions.

“A must-read for anyone interested in the nature of life, thought, and consciousness.”

David Rosenthal (Professor of Philosophy and Cognitive Science, Graduate School of the City University of New York)

“The homework presented by Le Dou in conclusion is worth readers’ careful consideration.

“A clear and refreshing prescription for difficult problems.”

--Booklist

“Many popular science writers have written the history of life, but LeDoux wants readers to enjoy it as well as remember it.

Thus, he divides the book into short, concise chapters, each explaining one evolutionary advance.

Like all great educators, the author begins with something simple.

… … a professional history of human behavior from the beginning.”

--Kirkus Review

Le Dou dates back to Aristotle.

"It deepens our understanding of this profound question."

Jeffrey Sachs (University Professor, Columbia University)

I chose the path to becoming smarter

How the human brain was born

Where do we stand in the natural world? In the primordial oceans of Earth, the primordial forms of life, the protocells, were created, and these biological events, layer upon layer, gave birth to us today.

This book confronts the deep history of life, a vast drama spanning four billion years, to understand ourselves as products of evolution.

All of our human actions today are connected to the history of evolution.

In the prologue, Joseph LeDoux, the author of this book and a world-renowned neuroscientist who discovered that the amygdala is the brain's fear center, explains why we need to know this long and arduous time.

“If you really want to understand human nature, you have to understand its evolutionary history.” (p. 17) Unique characteristics that were constantly added to organisms over a very long evolutionary process ultimately gave birth to us and our brains as we are today.

This characteristic can only be known by examining the natural history of life on Earth (see page 32). The more we can understand ourselves, the more clearly we can determine which parts of ourselves are related to what we inherited from various organisms.

This book explores the human brain and behavior across four billion years of evolutionary history.

While there have been many attempts to understand human nature through comparisons with closely related species such as primates and mammals, few books, like this one, trace back the origins of life, all the way to single-celled microorganisms, and examine the position of humans within the entire history of life.

Each chapter of the book is a concise 'one-topic' filled with short, concise reflections and insights.

If you want to know more specifically about a particular topic, you can read only the parts related to the topic of interest.

(For example, how did life begin, when did bacteria start behaving, how did sexual reproduction emerge, what process led to the emergence of multicellular organisms from single-celled organisms, how did the nervous system evolve, how did cognition and emotion evolve, what do we know about consciousness and the brain, etc.) After reading this book, you will gain insight into how our own unique abilities, such as thinking and emotion, that have allowed us to survive and thrive could have emerged from the survival skills of primitive microorganisms, and you will be forced to seriously consider not only your own past and future, but also the future of our species.

This book, LeDoux's fourth, deals with the issues of the 'brain', 'emotions', and 'consciousness' like his previous works (The Feeling Brain, Synapses and the Self, and Anxiety), but it unfolds the story on the bigger picture of 'evolution' and 'behavior'.

This is the ultimate question that Le Dou seeks to answer by weaving together five of the most fascinating topics in current science.

How did our brains shape us into the human beings we are today, capable of reasoning and reasoning, language and culture, and self-awareness?

We were born billions of years ago by single-celled microorganisms.

Inherited learning and memory abilities

While LeDoux acknowledges survival behaviors that date back to bacteria as universal traits shared by all organisms, he considers consciousness and emotions, which emerged in the human brain only very recently (only a few million years ago), to be uniquely human abilities.

Ledoux, struck by a fellow scientist's research showing that genes related to synaptic plasticity were similar in rodents, sea slugs, and even single-celled protozoans like paramecia and amoebas, decided to go back to the origins of life and see how we are similar to and different from other organisms.

'Behavior', which began simultaneously with the history of life, is a primary tool for survival, and all organisms exhibit several common survival behaviors.

The task is to avoid danger, obtain nutrients, maintain water and body temperature, and reproduce.

These primitive survival strategies of defense, energy management, fluid balance, and reproduction can also be found in bacteria that appeared on Earth 3.5 billion years ago as descendants of the 'most recent common ancestor of all life on Earth (LUCA)'.

Bacteria exhibit 'tactic behavior', using their ability to sense chemicals or light and their ability to move, to approach beneficial substances and flee from harmful substances.

It also regulates the concentration of water and electrolytes within the cell to prevent cell collapse, and regulates internal temperature by reorganizing biochemical processes to suit the external temperature.

And through cell division (asexual reproduction), they continue to thrive as the most numerous organism on Earth to this day.

What's even more surprising is that bacteria and their descendants, the single-celled protozoa, can acquire and store information about environmental conditions and then use it to respond more appropriately to environmental changes.

In other words, they also have the ability to learn and remember.

LeDoux defines memory as "a cellular function that facilitates survival by allowing us to obtain information from past experiences," adding that the nervous system is not necessarily required for learning and memory.

These solutions discovered by the first single-celled microorganisms for survival were successfully passed on to all organisms that appeared afterward, and have continued to lead to the complex survival behaviors of complex organisms, including humans.

What LeDoux is trying to say with 'survival behavior' is not that all organisms on Earth are biologically interconnected, but rather that "the roots of our everyday, routine behaviors are much older than we usually realize," and that "simple cells are also engaged in sophisticated survival activities, and these primitive survival activities continue in our lives today."

Humans and animals use it every day

The origin of cells called neurons

The first half of the book traces how these survival strategies were developed by primitive single-celled organisms, preserved by primitive multicellular organisms, and then, after the nervous system developed in early invertebrates, taken over by specialized cells called neurons, and later used daily by all animals, including humans.

In the process, we come to understand much more easily in the context of the overall evolution many interesting facts about life that we had previously known in fragments but did not know in detail.

Representative hypotheses include the story of how eukaryotes, in which a nucleus and mitochondria coexist, arose from archaea and the bacteria they consumed (endosymbiosis); the two-stage natural selection that unicellular organisms must go through in order for them to become multicellular organisms (first, the constituent cells must have similar genetic characteristics [fitness sorting], and second, a division of labor must occur in which the needs of the organism are prioritized over the needs of the cells [fitness delegation]); and the process by which neurons and the nervous system first appeared in cnidarians (such as hydra and jellyfish) (the sensory and motor cells of sponge larvae grew together and some of the sensory cells became long, and eventually these became the axons of neurons that communicate with electrical signals over long distances and transmit information with chemicals over short distances).

Finally, it reaches the human brain, correcting the classic errors that still have an impact today.

These are Ludwig Edinger's 'sequential formation theory' and Paul McLean's 'three-brain theory'.

The sequential formation theory claims that the human brain was structured as it is today by stacking layers of reptilian brain (basal ganglia), early mammalian brain (paleocortex), and mammalian brain (neocortex).

This theory, which is based on the idea that the human brain represents the pinnacle of evolution, has been refuted by numerous lines of evidence, including the discovery of homologous structures to the neocortex in reptiles and birds.

MacLean faithfully followed Edinger's theory and added explanations for the functions of each area, arguing that the basal ganglia were responsible for instincts, the palpebral cortex (which MacLean called the "limbic system") for emotions, and the neocortex for cognitive abilities.

However, the three-brain theory not only has all of Edinger's anatomical problems, but also has an incorrect explanation of brain function. The paleocortex (hippocampus and cingulate cortex) has been shown to contribute to cognitive activities such as memory, and the neocortex has also been shown to be involved in emotional experiences.

It is not present in the brains of other primates.

The prefrontal cortex, a unique part of the human brain responsible for deliberative cognition

We humans have been able to thrive by choosing to become smarter rather than bigger or more agile.

Cognition is a product of biological processes made possible by the nervous system, and it has been proven through numerous experiments that it varies from organism to organism.

Bacteria, protozoa, and cnidarians only have Pavlovian simple associations (they approach a light when it is close to food), while protozoa, fish, amphibians, and reptiles only have Pavlovian cognition (if they feel nauseated after eating food, they avoid that food thereafter), and mammals and birds have goal-directed instrumental cognition (if they press the lever while the light is flashing, they get food).

But only humans are capable of conscious deliberation (problem solving through memory, reasoning, and prediction, not trial and error).

The second half of the book examines the functional roles of each region of the human brain and how their networks influence perception, memory, cognition, and emotion—our conscious experiences.

Le Dou focuses on the prefrontal cortex, and particularly the 'frontal pole', as the core area of consciousness.

The prefrontal cortex is a unique region of the human brain, not found in other primates. It is where our most abstract conceptual representations are created and processed, and is responsible for deliberative cognition such as long-term goals, future planning, hierarchical relationship reasoning, and problem solving.

The frontal pole is also related to self-awareness, that is, self-consciousness.

It is all thanks to self-awareness that we can distinguish ourselves from others and understand the minds of others, and this is an ability that only humans possess.

In the history of survival strategies

The human emotions and mind that are created

We feel fear when we react to danger.

Because these two experiences often occur together, we think that fear is what causes such a response.

But according to Le Dou, this is not true.

The brain systems that control survival behavior and the brain systems that govern the conscious feelings (emotions) experienced when performing those behaviors are separate from each other.

“Actions and feelings occur simultaneously, not because feelings cause actions, but because each system responds to the same stimulus.” Although actions are often thought of as tools of the mind, mental activities such as the mind arose much later in evolutionary history.

Linking behavior and mental activity is merely an 'evolutionary post-hoc explanation'.

Instead of the confusing expression 'fear circuit' that seems to cause mental states to cause behavior, LeDoux introduced the term 'survival circuit', arguing that behavior follows the mechanism of 'survival stimulus - survival circuit - survival response', but emotions (feelings) are processed separately in the cortical cognitive circuit (higher-order prefrontal network).

For example, when the sensory system receives information about a danger such as a snake underfoot, the defensive survival state (defensive survival circuit) is activated in the amygdala, causing behavioral responses (freezing, avoidance) and physiological responses (trembling, cold sweat), and at the same time, inducing feelings (fear, anxiety) in the cortical cognitive circuit.

According to LeDoux's multistate hierarchical model, conscious fear arises from cognitively interpreting a situation as dangerous.

In other words, it is not the amygdala that causes fear, but rather our individual fear schemas (our knowledge of danger acquired throughout our lives), and fear is not universal, but always frightening 'to me.'

Emotions are self-aware consciousness, and “without self, there are no emotions.”

This fact explains why many pharmaceutical companies have so far failed to develop drugs that reduce fear and anxiety.

Most drugs are developed by measuring behavioral changes in animals, but this only affects survival circuits and not the cortical cognitive circuits that actually cause fear and anxiety.

In animal consciousness and human consciousness

Similarities and Differences

If emotions are created in the above way, then since only humans can experience self-aware consciousness, we can say that emotions also arise only in humans.

At first glance, this sounds like depriving other species, especially animals close to humans, of consciousness and emotions.

However, Le Dou does not deny that animals have conscious experiences.

However, I believe that it is possible that animals' conscious experiences are quite different from those of humans, and that it would be extremely difficult to scientifically confirm this without language.

If we accept this fact, we should be more cautious when saying that other animals have conscious experiences similar to humans.

Since Darwin argued that animals also have emotions, citing similarities in human and animal behavior, the tendency toward 'anthropocentrism' and 'anthropomorphism' has been deeply rooted in academia.

When we assume that other animals experience certain conscious experiences (feeling fear, hunger, thirst, sexual pleasure) just because we experience them during our survival behaviors (defense, energy management, fluid balance, reproduction), we are simply projecting our own experiences onto other organisms.

Contrary to the claims of anthropomorphism advocates like Frans de Waal, Jane Goodall, and Marc Bekoff (“If closely related species exhibit the same behavior, then the underlying mental processes are probably the same”), observation of behavior alone does not link behavior to consciousness.

This is because behavior is not only controlled consciously, but also unconsciously.

Unfortunately, however, current animal research is preoccupied with “accumulating evidence to support the intuition that consciousness is involved,” rather than determining whether specific behaviors are controlled consciously or unconsciously.

Anthropomorphic thinking may have been hardwired into our genes by natural selection because it was useful for predicting and controlling the behavior of other animals.

But just because it is human nature and natural doesn't mean it is scientifically correct.

Science must be based on actual facts, not intuition.

Humans are not the pinnacle of evolution.

The uniquely human self-aware consciousness that created and destroyed civilization

LeDoux argues that emotions are a refractive adaptation of language and self-awareness (traits that arose as a byproduct of other traits but were naturally selected for their utility), and that the ability to personalize values (“How dangerous is this 'to me'?”) was selected for because it was more effective for survival than the unconscious survival behavior of simply detecting and avoiding danger.

Just because LeDoux identifies emotions and consciousness as uniquely human characteristics, he doesn't mean he regards humans as the pinnacle of evolution. ("In the long history of four billion years, such uniqueness is merely a footnote.") Rather, in the epilogue, LeDoux highlights the negative aspects of self-aware consciousness.

Self-awareness has brought about great achievements, including today's science, technology, and culture and art, but on the other hand, it has also made possible mental traits such as distrust, hatred, greed, and selfishness, "which could destroy our species." LeDoux warns of a dark future brought about by ecological destruction, including climate change and mass extinction, and urges a conscious awakening to rapid cognitive and cultural evolution instead of slow biological evolution, that is, to our way of life in which we live together with other species.

“LeDoux is a leading scientist leading the important work today to explain the brain mechanisms of emotional states.

In this latest work, LeDoux seeks to link the survival abilities of single-celled microorganisms to our unique ability to survive.

This human capacity is profoundly influenced by our ability to think and feel, to contemplate our own past and future, as well as that of humanity.

“It is a wonderful book, and, as Le Dou says, truly ‘our own deep history.’”

--Eric Kandel (author of "Faults of the Mind," University Professor, Columbia University, 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine)

“LeDoux’s new book begins with the biology of simple organisms and ends with a rigorously argued argument for viewing human emotions and consciousness as higher-order cognitive processes at the peak of biological complexity.

Even those who don't entirely agree with his views (though I do agree with many of them), cannot help but appreciate and celebrate his accomplishments.”

--Antonio Damasio, author of "The Evolution of Feelings" and professor of neuroscience at the University of Southern California

“LeDoux has written an extraordinary book, full of insights that illuminate many aspects of how we humans and other animals came to be what we are today.

“It is a very readable book for the general public, and is full of useful information for other neuroscientists as well.”

Daniel Levitin, author of The Organized Brain and Professor Emeritus of Psychology and Behavioral Neuroscience, McGill University

“‘How does our mind make us different from other species?’ Ledoux deepens our understanding of this profound question, which dates back to Aristotle.

There is no better guide than Le Dou.

LeDoux is one of the world's leading neuroscientists, working at the forefront of behavior, emotion, and consciousness.

Ledoux cleverly and wittily traces the 4 billion-year history of life, showing how humans, while sharing basic behaviors with single-celled organisms, have made the leap to reflective self-awareness, the only species in the universe to do so.

“It was so interesting and exciting to read.”

--Jeffrey Sachs (University Professor, Columbia University)

“A very entertaining and informative journey covering the origins of life and the emergence of creatures with complex mental lives.

A vital perspective on how we humans came to have intelligence, consciousness, and emotions.

“From biology to psychology, everything is a masterpiece.”

--Susan Schneider (NASA/Library of Congress Astrobiology Researcher)

“LeDoux presents his own remarkable synthesis of zoology, neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy.

His central themes are the emergence of consciousness through the evolution of the nervous system, the behaviors it controls, and the Tree of Consciousness, not the Tree of Life, where consciousness leads us.

“A wonderful book that broadens your mind.”

--Trevor Robbins (Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, University of Cambridge)

“A fascinating book that shows the grand evolution of life, from molecules to consciousness.

“LeDoux offers a fresh look at core ideas in this field, including exciting new insights into how our brains work.”

--Marion Dawkins (Professor of Animal Behavior, Oxford University)

“Le Dou is a rare scientist who sees both the trees and the forest.

This incredibly easy-to-read book will appeal to a wide range of readers.

An introduction to the evolution of life is combined with a discussion of psychological processes that need to be illuminated.

The discussion is sophisticated, historically informed, and provocative.

“An original work by a renowned scientist who understands the brain and its relationship to psychological events.”

--Jerome Kagan (Professor Emeritus of Psychology, Harvard University)

“The most important thing to know about consciousness is that it evolved.

In this masterpiece, LeDoux reveals not only the overall picture of that evolution, but also crucial details of the complex nervous system that allowed consciousness to emerge in humans.”

--Christopher Frith (psychologist, professor emeritus, University College London)

“It’s always wise to try to understand the context.

Placing ourselves within the context of 4 billion years of history is a brilliant way to change perspective.

Short but interesting articles ask:

“What is consciousness?” “What are emotions?” And most of all, “Who am I?” The answers will surprise you.”

--Hazel Rose Marcus, cultural psychologist and professor of behavioral sciences at Stanford University

“This book shows the continuity of how biological processes produce behavior, from the simplest to the most complex organisms.

The book supports the argument that the processes that drive the behavior of complex organisms like us and those that lead to conscious awareness are quite different.

Le Dou presents all this with masterful knowledge of the big picture and fascinating detail, concluding with his own theory of consciousness and emotions.

“A must-read for anyone interested in the nature of life, thought, and consciousness.”

David Rosenthal (Professor of Philosophy and Cognitive Science, Graduate School of the City University of New York)

“The homework presented by Le Dou in conclusion is worth readers’ careful consideration.

“A clear and refreshing prescription for difficult problems.”

--Booklist

“Many popular science writers have written the history of life, but LeDoux wants readers to enjoy it as well as remember it.

Thus, he divides the book into short, concise chapters, each explaining one evolutionary advance.

Like all great educators, the author begins with something simple.

… … a professional history of human behavior from the beginning.”

--Kirkus Review

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: April 23, 2021

- Page count, weight, size: 548 pages | 794g | 152*224*26mm

- ISBN13: 9791166890147

- ISBN10: 1166890147

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)