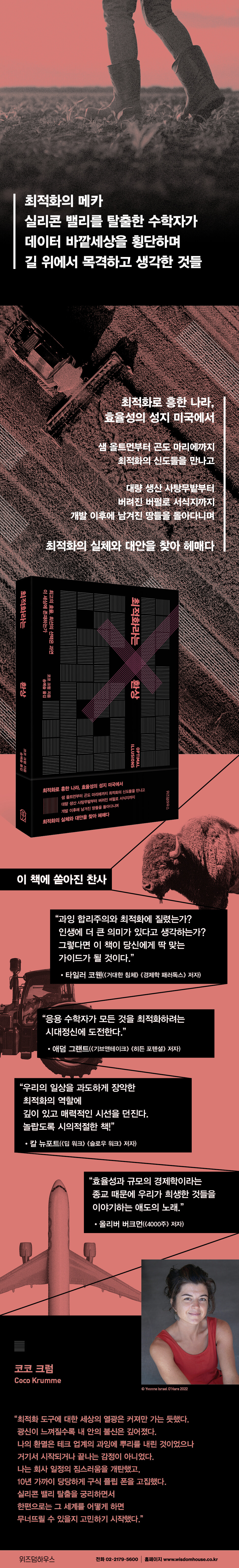

The illusion of optimization

|

Description

Book Introduction

In the United States, a country that thrived on optimization and a mecca of efficiency

Wandering through the reality of optimization and finding alternatives

Optimization is the principle that makes the modern world work.

We are obsessed with productivity and optimal performance, and we pursue efficiency in our daily lives.

How did a single mathematical concept take on such a profound cultural dimension? And what are we losing as we gain efficiency? The author, an applied mathematician and data scientist, traces the remarkable history of optimization, rooted in America's founding principles and present-day society, through the colorful stories of a diverse range of individuals, from Silicon Valley entrepreneur Sam Altman and lifestyle guru and organizing expert Marie Kondo to farmers opposing GMO cultivation and indigenous people dedicated to restoring endangered buffalo.

It relentlessly delves into the metaphor of optimization that has engulfed the entire world, exposes the enormous gamble we are making within it, and urges us to consider what attitude we should adopt to move forward without being swayed or dragged along.

Wandering through the reality of optimization and finding alternatives

Optimization is the principle that makes the modern world work.

We are obsessed with productivity and optimal performance, and we pursue efficiency in our daily lives.

How did a single mathematical concept take on such a profound cultural dimension? And what are we losing as we gain efficiency? The author, an applied mathematician and data scientist, traces the remarkable history of optimization, rooted in America's founding principles and present-day society, through the colorful stories of a diverse range of individuals, from Silicon Valley entrepreneur Sam Altman and lifestyle guru and organizing expert Marie Kondo to farmers opposing GMO cultivation and indigenous people dedicated to restoring endangered buffalo.

It relentlessly delves into the metaphor of optimization that has engulfed the entire world, exposes the enormous gamble we are making within it, and urges us to consider what attitude we should adopt to move forward without being swayed or dragged along.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

preface

Chapter 1: The Flat World Rediscovered

Chapter 2 Leaving Las Vegas

Chapter 3: The Church in the High Desert

Chapter 4: The Collapse of Metaphor

Chapter 5: False Gods

Chapter 6: The Betrayal of Optimization

Chapter 7 After the Gold Rush

Chapter 8 Babylonia

Acknowledgements

main

Chapter 1: The Flat World Rediscovered

Chapter 2 Leaving Las Vegas

Chapter 3: The Church in the High Desert

Chapter 4: The Collapse of Metaphor

Chapter 5: False Gods

Chapter 6: The Betrayal of Optimization

Chapter 7 After the Gold Rush

Chapter 8 Babylonia

Acknowledgements

main

Detailed image

Into the book

When I was about half my age, my younger brother got really worked up and said this to me:

“Stop obsessing over optimization.” We were walking through a small town we didn’t know very well.

I had a few hours to spare and a few places to see.

Our stops included a grocery store, a hardware store, and a restaurant for lunch.

It was before smartphones and we didn't even have maps.

I planned a route that would maximize my chances of visiting all my destinations in as little time as possible.

Then my younger brother told me to just keep my mouth shut and enjoy my time.

My brother was right.

On that sunny day, there wasn't much for us to do other than enjoy the nice weather, walks, and conversations.

There was no reason to pursue optimization.

--- p.18

Like stories and metaphors, models are a way of giving shape to reality.

The reality thus created shapes our perspective on the world, solidifying and reinforcing the chosen framework.

By embracing efficiency as our top priority, we've eliminated the unmeasurable and unoptimizable, leaving the metaphor of optimization to consume other worldviews.

We fooled ourselves into thinking that optimization could solve optimization problems.

As a result, paradoxically, our ability to change has stagnated.

--- p.57

The third shift combines the previous two to systematize individual action for a better world.

Many of America's greatest inventions, from the interstate highway system to the supercomputer, could have happened without relying on this way of thinking, but if they had, they would not have had such a profound impact on the American psyche.

The very American ideals—the drive to move forward, the pursuit of economic growth and prosperity, the management of a more just system of governance—are deeply connected to the idea that we can design a more complete existence and become that.

The nature of this transition, though not overtly religious, is closely tied to the Protestant faith that dominated early America.

It may be an exaggeration to say that optimization is the gospel, and that places that physically represent optimization, like the desert where the 777 jet is abandoned, are holy places.

The history of optimization is more superficial than you might think, and its devotees may not think of themselves as worshippers of optimization.

However, optimization is similar to faith in that it processes the material world through shared rules and customs.

At the same time, optimization is also a set of everyday practices: going faster, packing more in, saving money, saving for retirement, being more productive, and trying not to fall behind others.

--- p.105~106

After giving birth to her third child, Kondo realized she had too much to do.

In one interview, he delivers his message with sincerity, as always.

“Since that vision, I have made it a priority to make time for pleasure in life, and the busier I get, the more I do this.

“I make time for myself to enjoy and do things I want to do.” Kondo is a product and archetype of our times.

He is a great optimizer.

But at the same time, he is also a true believer who, through organizing, has restored joy and aesthetics to our impoverished language.

I wonder what the family whose Los Angeles ranch house Kondo helped clean on the Netflix show is doing these days.

Are we going back to our old ways, living in the same old house, with a new pile of junk? Or are we going the other way, pursuing extreme minimalism? Or is it somewhere in between?

--- p.134

As credit default swaps ballooned during the 2008 financial crisis, defaults on Florida ranch homes began to spread slowly.

In California, fire management has been neglected for decades, and suburban homes have slowly encroached on forests filled with flammable trees.

Small cracks in the supply chain have been appearing since the beginning of this century, but no one paid attention until the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

So the collapse seemed sudden.

Gradually, abstraction and automation accumulate, fueling dry fuel and excessive debt.

Gradually, redundancy disappears and vulnerability grows.

Gradually, those responsible for the system lose sight of the system's blueprint and vulnerabilities.

Gradually, we become more eager to hide our problems.

Then suddenly, the power goes out and the pipes freeze.

--- p.139

Optimization works most smoothly and purely when boundaries are established and it is a zero-sum game.

You should not be able to add or subtract pieces from the board, and you should not be able to trade with people outside the game.

If natural resources like oil or gold seem infinite, it's an explorer's game.

But once the land has been surveyed and the mines mined, the boards are passed to managers who manage the territory and master the maps.

For too long, we have overlooked this turning point, blinded by the promise of endless resources and limitless growth.

Financial expert Peter Atwater says of a stock market crash in early 2022:

“This is not a ‘tech sell-off.’

This is a major price adjustment for abstraction.

“Our dreams were filled with bubbles.” A similar argument can be made about the myth of efficiency.

Our persistent fascination with efficiency stemmed in part from the mistaken assumption that we could extract growth forever from finite systems.

--- p.145

When he co-founded OpenAI with Musk, Altman saw AI as a powerful tool and a potential world-saving solution. AI technology was rapidly advancing and would continue to do so.

Altman posted online that this technology would soon generate enough wealth for every adult to receive $13,500 a year, and his claims were reported by major media outlets.

But he later confided to me that this number was an unfounded claim.

That's not what I meant exactly.

But the idea is valid.

Automation will free up far more leisure time than we have today, allowing us to dedicate our productive energy to creative pursuits and inventing new things.

--- p.191

My heart was also sincere in coming here, away from optimization.

But I knew that my migration was dependent.

Just as Nathan and Sage depend on the railroad to run their bakery on the island, I still believe in the idea of optimization as the ultimate escape route.

It's not just me.

Many people are trying to grasp something new, but they don't know exactly what it is.

We only know the metaphor and the opposing argument.

Join or leave.

The middle is where everything is uncertain.

According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, the phenomenon of "quiet quitting" has become popular recently.

This means working just enough so that you don't get cut off.

One young man explains the concept this way:

“I reject the idea of working beyond limits.

(Omitted) They no longer follow the hustle culture-centric mindset that work should be their life.” According to the article, many young people “reject the idea that productivity is the primacy of everything.

“Because we can’t find a suitable reward for it.” Even this rejection of efficiency is supported by the framework of efficiency.

If so, we cannot help but ask this question:

What exactly is the reward?

--- p.254~255

Jane Jacobs writes:

“Even when societies were much poorer than they are today, we could afford the costs and inefficiencies that are inherent in the survival of society.

How could that be possible? How could a poor but vibrant culture survive even today? Ironically, optimization hasn't given us a wealth of choices, but rather injected us with a false excess.

Jacobs answers his own question:

If we loosen the reins, we can regain some space and space, or “a variety of individuals who fit into and contribute to the culture in different ways.”

In other words, the redundancy and closedness of small groups actually contribute to the vitality of the whole.

“Stop obsessing over optimization.” We were walking through a small town we didn’t know very well.

I had a few hours to spare and a few places to see.

Our stops included a grocery store, a hardware store, and a restaurant for lunch.

It was before smartphones and we didn't even have maps.

I planned a route that would maximize my chances of visiting all my destinations in as little time as possible.

Then my younger brother told me to just keep my mouth shut and enjoy my time.

My brother was right.

On that sunny day, there wasn't much for us to do other than enjoy the nice weather, walks, and conversations.

There was no reason to pursue optimization.

--- p.18

Like stories and metaphors, models are a way of giving shape to reality.

The reality thus created shapes our perspective on the world, solidifying and reinforcing the chosen framework.

By embracing efficiency as our top priority, we've eliminated the unmeasurable and unoptimizable, leaving the metaphor of optimization to consume other worldviews.

We fooled ourselves into thinking that optimization could solve optimization problems.

As a result, paradoxically, our ability to change has stagnated.

--- p.57

The third shift combines the previous two to systematize individual action for a better world.

Many of America's greatest inventions, from the interstate highway system to the supercomputer, could have happened without relying on this way of thinking, but if they had, they would not have had such a profound impact on the American psyche.

The very American ideals—the drive to move forward, the pursuit of economic growth and prosperity, the management of a more just system of governance—are deeply connected to the idea that we can design a more complete existence and become that.

The nature of this transition, though not overtly religious, is closely tied to the Protestant faith that dominated early America.

It may be an exaggeration to say that optimization is the gospel, and that places that physically represent optimization, like the desert where the 777 jet is abandoned, are holy places.

The history of optimization is more superficial than you might think, and its devotees may not think of themselves as worshippers of optimization.

However, optimization is similar to faith in that it processes the material world through shared rules and customs.

At the same time, optimization is also a set of everyday practices: going faster, packing more in, saving money, saving for retirement, being more productive, and trying not to fall behind others.

--- p.105~106

After giving birth to her third child, Kondo realized she had too much to do.

In one interview, he delivers his message with sincerity, as always.

“Since that vision, I have made it a priority to make time for pleasure in life, and the busier I get, the more I do this.

“I make time for myself to enjoy and do things I want to do.” Kondo is a product and archetype of our times.

He is a great optimizer.

But at the same time, he is also a true believer who, through organizing, has restored joy and aesthetics to our impoverished language.

I wonder what the family whose Los Angeles ranch house Kondo helped clean on the Netflix show is doing these days.

Are we going back to our old ways, living in the same old house, with a new pile of junk? Or are we going the other way, pursuing extreme minimalism? Or is it somewhere in between?

--- p.134

As credit default swaps ballooned during the 2008 financial crisis, defaults on Florida ranch homes began to spread slowly.

In California, fire management has been neglected for decades, and suburban homes have slowly encroached on forests filled with flammable trees.

Small cracks in the supply chain have been appearing since the beginning of this century, but no one paid attention until the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

So the collapse seemed sudden.

Gradually, abstraction and automation accumulate, fueling dry fuel and excessive debt.

Gradually, redundancy disappears and vulnerability grows.

Gradually, those responsible for the system lose sight of the system's blueprint and vulnerabilities.

Gradually, we become more eager to hide our problems.

Then suddenly, the power goes out and the pipes freeze.

--- p.139

Optimization works most smoothly and purely when boundaries are established and it is a zero-sum game.

You should not be able to add or subtract pieces from the board, and you should not be able to trade with people outside the game.

If natural resources like oil or gold seem infinite, it's an explorer's game.

But once the land has been surveyed and the mines mined, the boards are passed to managers who manage the territory and master the maps.

For too long, we have overlooked this turning point, blinded by the promise of endless resources and limitless growth.

Financial expert Peter Atwater says of a stock market crash in early 2022:

“This is not a ‘tech sell-off.’

This is a major price adjustment for abstraction.

“Our dreams were filled with bubbles.” A similar argument can be made about the myth of efficiency.

Our persistent fascination with efficiency stemmed in part from the mistaken assumption that we could extract growth forever from finite systems.

--- p.145

When he co-founded OpenAI with Musk, Altman saw AI as a powerful tool and a potential world-saving solution. AI technology was rapidly advancing and would continue to do so.

Altman posted online that this technology would soon generate enough wealth for every adult to receive $13,500 a year, and his claims were reported by major media outlets.

But he later confided to me that this number was an unfounded claim.

That's not what I meant exactly.

But the idea is valid.

Automation will free up far more leisure time than we have today, allowing us to dedicate our productive energy to creative pursuits and inventing new things.

--- p.191

My heart was also sincere in coming here, away from optimization.

But I knew that my migration was dependent.

Just as Nathan and Sage depend on the railroad to run their bakery on the island, I still believe in the idea of optimization as the ultimate escape route.

It's not just me.

Many people are trying to grasp something new, but they don't know exactly what it is.

We only know the metaphor and the opposing argument.

Join or leave.

The middle is where everything is uncertain.

According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, the phenomenon of "quiet quitting" has become popular recently.

This means working just enough so that you don't get cut off.

One young man explains the concept this way:

“I reject the idea of working beyond limits.

(Omitted) They no longer follow the hustle culture-centric mindset that work should be their life.” According to the article, many young people “reject the idea that productivity is the primacy of everything.

“Because we can’t find a suitable reward for it.” Even this rejection of efficiency is supported by the framework of efficiency.

If so, we cannot help but ask this question:

What exactly is the reward?

--- p.254~255

Jane Jacobs writes:

“Even when societies were much poorer than they are today, we could afford the costs and inefficiencies that are inherent in the survival of society.

How could that be possible? How could a poor but vibrant culture survive even today? Ironically, optimization hasn't given us a wealth of choices, but rather injected us with a false excess.

Jacobs answers his own question:

If we loosen the reins, we can regain some space and space, or “a variety of individuals who fit into and contribute to the culture in different ways.”

In other words, the redundancy and closedness of small groups actually contribute to the vitality of the whole.

--- p.259

Publisher's Review

Optimization that has taken over the world

A desperately needed new approach

“A wonderfully timely book!”_Carl Newport

“Applied mathematicians challenge the zeitgeist of optimizing everything.” —Adam Grant

A mathematician who escaped Silicon Valley, the mecca of optimization

Things I witnessed and thought about on the road while crossing the world outside of data.

Optimization is the principle that makes the modern world work.

We can make and transport things cheaper and faster than ever before.

Optimized models power everything from airline schedules to dating sites.

Optimization is now deeply embedded in our material reality, as well as in the technologies and mindsets that shape what we produce there.

How did a single mathematical concept shape such a vast culture? And what are we losing in the efficiencies we gain? Coco Crum, fascinated by mathematical models, studied mathematics at MIT, worked as a data scientist in Silicon Valley, and founded and ran a science consulting firm.

I once pursued “more data, more models, more solutions” with burning passion, but somehow that romanticism gradually faded.

As the world became more obsessed with optimization, Crumb's inner distrust deepened.

My disillusionment was rooted in the excesses of the tech industry, but it didn't begin or end there.

I lamented the burden of corporate schedules and proudly clung to my old flip phone for nearly a decade.

While I was contemplating escaping Silicon Valley, I also began to wonder how I could bring that world down.

(Page 10)

In 2020, Crum suddenly began to question the values of "optimization" and "efficiency" that he had been pursuing as if they were the right answer, and he began traveling around the United States, meeting people.

"The Illusion of Optimization" is the result of that fascinating exploration and adventure.

In this book, Crum traces the remarkable history of optimization, rooted in America's founding principles and present in modern society, through the colorful stories of people ranging from Silicon Valley entrepreneur Sam Altman and lifestyle guru and organizing expert Marie Kondo to farmers opposing GMO cultivation and indigenous people who have dedicated their lives to restoring the endangered buffalo.

The illusion that if you turn everything in the world into numbers, you will grow forever.

The bulldozer of optimization, disguised as efficiency and profitability, has buried 'leisure,' 'place,' and 'scale!'

“More.

Better.

“Faster.” This expression has taken over not only business but also everyday life.

New smartphones, upgraded every year, promise faster speeds and clearer picture quality.

Numerous diet and health companies promise to help you achieve your desired weight and body shape in a short period of time.

Any small business owner is inevitably asked when they will scale up and expand.

In this way, optimization has become the lens through which we view the world.

As a result, we look at everything in isolation, judging comparative advantage, performance, and productivity, and we refine all kinds of routines to be more efficient.

We utilize nature and design the world around us, shifting our focus from observation to control.

Above all, we dream of eternal growth, anticipating a destiny of ever-increasing progress and moving forward toward greater heights.

This momentum toward optimization was particularly evident in the United States.

It is no exaggeration to say that the United States is a country that thrives on optimization and is a mecca of efficiency.

A legion of efficiency experts and folk heroes, led by Henry Ford, convinced American politicians and the public that economies of scale could lead to greater prosperity.

One of the products is the extremely large-scale American agriculture.

That's why the first place Crum turned to to explore optimization was the sugar beet farms of the Dakota Plains, which produce massive amounts of sugar.

Thanks to machines that replaced human labor, robust seeds, and chemicals that warded off pests and diseases, farmland expanded endlessly and food became endlessly abundant.

In return, it was all too easy to ignore the fact that machines deplete the soil, chemicals are harmful to human health, and fertilizers pollute drinking water.

We have benefited from optimization while pursuing the single goal of efficiency and profitability.

The economy has grown, the population has increased, and the world has developed, but something feels empty.

The Dakota plains, covered with sugar beet crops, look somehow empty.

That's the flip side of optimization.

We have lost slack, place, and scale.

We have lost the sense of scale that allows us to choose the right place (land) to apply various farming methods, whether it is large or small, short-term or long-term, depending on our individual circumstances.

We, society as a whole, willingly agreed to this bargain, whether we knew it or not.

We once indulged in the sweet fruits of our labor, but now the price is slowly overshadowing us.

Depending on who you ask, the answer will vary, but we are now living in an age of anxiety, an age of narcissism, a fourth turning, or the fall of empires.

The neoliberal order and growth are coming to an end, authoritarianism is on the rise, and the curtain is rising on a dark age or climate catastrophe.

The sense of apocalypse is awakening.

According to Forbes, television programs with a pre-apocalypse theme are gaining popularity, especially among millennials.

Optimization has consumed our time, attention, and even our future.

We've filled our ships and our schedules, but we've left a gap as to why.

(Page 13)

“What if neither strengthening optimization nor escaping optimization is the answer?”

In an era where limitless development and continuous growth have stalled, we must face the "illusion of optimization" head-on.

Even non-mathematicians will likely sympathize with the disillusionment with excessive efficiency.

We strive to use our time and money as productively and sparingly as possible, but at some point we feel overwhelmed and frustrated when we encounter problems that cannot be solved through optimization.

"Am I doing the right thing? What is the right thing to do?" This feeling manifests itself in skyrocketing rates of depression and anxiety, increasingly visible breakdowns in supply chains and society, the high cost of working in big cities, and plummeting marriage and birth rates.

There's a pervasive sense that unbridled growth isn't for us, that we've lost some sense of agency despite the countless products of optimization—cheap products and high-rise buildings—but no viable alternative is in sight.

Optimization advocates argue that this discontent can be alleviated by increasing efficiency.

Those on the other side, on the other hand, counter that we must escape efficiency or nullify it altogether.

The problem, however, is that both methods perpetuate the advantage of optimization.

The first method is a deoptimization method, which actually strengthens optimization, while the second method maintains the advantage of optimization by cramming all the chips currently available into the past standard.

What if neither strengthening optimization nor escaping it is the answer? Our livelihoods, our quality of life, our relationships with others, and our way of understanding the world all depend on optimization.

But just because we can't leave optimization behind forever, ignoring the seething discontent and the sick and decaying nature and world is not the answer.

In this context, Crum argues that we must seriously consider what perspective and attitude we should adopt in order to move forward without being swayed or dragged along by optimization.

We cannot move forward unless we acknowledge the ruins that lie beneath the land where our illegally occupied mansions and air logistics hubs are being built.

Perhaps what we need to do now is not complete reconciliation or dissolution, but rather choosing a perspective.

(Page 278)

In this book, Crum persistently questions the worldview of 'optimization' that has taken over the world.

And in the end, it boldly suggests that neither blind acceptance nor radical resistance is the answer, and that we should let go of the very language of 'optimization' that surrounds us.

For those who feel the need to put the brakes on the breathtakingly rapid pace of technological advancement and the relentless drive toward growth and development, "The Illusion of Optimization" will offer an intellectual pleasure, allowing them to concretize vague concerns through a variety of experiences and examples, and an opportunity to shift perspectives they'd never even considered breaking.

A desperately needed new approach

“A wonderfully timely book!”_Carl Newport

“Applied mathematicians challenge the zeitgeist of optimizing everything.” —Adam Grant

A mathematician who escaped Silicon Valley, the mecca of optimization

Things I witnessed and thought about on the road while crossing the world outside of data.

Optimization is the principle that makes the modern world work.

We can make and transport things cheaper and faster than ever before.

Optimized models power everything from airline schedules to dating sites.

Optimization is now deeply embedded in our material reality, as well as in the technologies and mindsets that shape what we produce there.

How did a single mathematical concept shape such a vast culture? And what are we losing in the efficiencies we gain? Coco Crum, fascinated by mathematical models, studied mathematics at MIT, worked as a data scientist in Silicon Valley, and founded and ran a science consulting firm.

I once pursued “more data, more models, more solutions” with burning passion, but somehow that romanticism gradually faded.

As the world became more obsessed with optimization, Crumb's inner distrust deepened.

My disillusionment was rooted in the excesses of the tech industry, but it didn't begin or end there.

I lamented the burden of corporate schedules and proudly clung to my old flip phone for nearly a decade.

While I was contemplating escaping Silicon Valley, I also began to wonder how I could bring that world down.

(Page 10)

In 2020, Crum suddenly began to question the values of "optimization" and "efficiency" that he had been pursuing as if they were the right answer, and he began traveling around the United States, meeting people.

"The Illusion of Optimization" is the result of that fascinating exploration and adventure.

In this book, Crum traces the remarkable history of optimization, rooted in America's founding principles and present in modern society, through the colorful stories of people ranging from Silicon Valley entrepreneur Sam Altman and lifestyle guru and organizing expert Marie Kondo to farmers opposing GMO cultivation and indigenous people who have dedicated their lives to restoring the endangered buffalo.

The illusion that if you turn everything in the world into numbers, you will grow forever.

The bulldozer of optimization, disguised as efficiency and profitability, has buried 'leisure,' 'place,' and 'scale!'

“More.

Better.

“Faster.” This expression has taken over not only business but also everyday life.

New smartphones, upgraded every year, promise faster speeds and clearer picture quality.

Numerous diet and health companies promise to help you achieve your desired weight and body shape in a short period of time.

Any small business owner is inevitably asked when they will scale up and expand.

In this way, optimization has become the lens through which we view the world.

As a result, we look at everything in isolation, judging comparative advantage, performance, and productivity, and we refine all kinds of routines to be more efficient.

We utilize nature and design the world around us, shifting our focus from observation to control.

Above all, we dream of eternal growth, anticipating a destiny of ever-increasing progress and moving forward toward greater heights.

This momentum toward optimization was particularly evident in the United States.

It is no exaggeration to say that the United States is a country that thrives on optimization and is a mecca of efficiency.

A legion of efficiency experts and folk heroes, led by Henry Ford, convinced American politicians and the public that economies of scale could lead to greater prosperity.

One of the products is the extremely large-scale American agriculture.

That's why the first place Crum turned to to explore optimization was the sugar beet farms of the Dakota Plains, which produce massive amounts of sugar.

Thanks to machines that replaced human labor, robust seeds, and chemicals that warded off pests and diseases, farmland expanded endlessly and food became endlessly abundant.

In return, it was all too easy to ignore the fact that machines deplete the soil, chemicals are harmful to human health, and fertilizers pollute drinking water.

We have benefited from optimization while pursuing the single goal of efficiency and profitability.

The economy has grown, the population has increased, and the world has developed, but something feels empty.

The Dakota plains, covered with sugar beet crops, look somehow empty.

That's the flip side of optimization.

We have lost slack, place, and scale.

We have lost the sense of scale that allows us to choose the right place (land) to apply various farming methods, whether it is large or small, short-term or long-term, depending on our individual circumstances.

We, society as a whole, willingly agreed to this bargain, whether we knew it or not.

We once indulged in the sweet fruits of our labor, but now the price is slowly overshadowing us.

Depending on who you ask, the answer will vary, but we are now living in an age of anxiety, an age of narcissism, a fourth turning, or the fall of empires.

The neoliberal order and growth are coming to an end, authoritarianism is on the rise, and the curtain is rising on a dark age or climate catastrophe.

The sense of apocalypse is awakening.

According to Forbes, television programs with a pre-apocalypse theme are gaining popularity, especially among millennials.

Optimization has consumed our time, attention, and even our future.

We've filled our ships and our schedules, but we've left a gap as to why.

(Page 13)

“What if neither strengthening optimization nor escaping optimization is the answer?”

In an era where limitless development and continuous growth have stalled, we must face the "illusion of optimization" head-on.

Even non-mathematicians will likely sympathize with the disillusionment with excessive efficiency.

We strive to use our time and money as productively and sparingly as possible, but at some point we feel overwhelmed and frustrated when we encounter problems that cannot be solved through optimization.

"Am I doing the right thing? What is the right thing to do?" This feeling manifests itself in skyrocketing rates of depression and anxiety, increasingly visible breakdowns in supply chains and society, the high cost of working in big cities, and plummeting marriage and birth rates.

There's a pervasive sense that unbridled growth isn't for us, that we've lost some sense of agency despite the countless products of optimization—cheap products and high-rise buildings—but no viable alternative is in sight.

Optimization advocates argue that this discontent can be alleviated by increasing efficiency.

Those on the other side, on the other hand, counter that we must escape efficiency or nullify it altogether.

The problem, however, is that both methods perpetuate the advantage of optimization.

The first method is a deoptimization method, which actually strengthens optimization, while the second method maintains the advantage of optimization by cramming all the chips currently available into the past standard.

What if neither strengthening optimization nor escaping it is the answer? Our livelihoods, our quality of life, our relationships with others, and our way of understanding the world all depend on optimization.

But just because we can't leave optimization behind forever, ignoring the seething discontent and the sick and decaying nature and world is not the answer.

In this context, Crum argues that we must seriously consider what perspective and attitude we should adopt in order to move forward without being swayed or dragged along by optimization.

We cannot move forward unless we acknowledge the ruins that lie beneath the land where our illegally occupied mansions and air logistics hubs are being built.

Perhaps what we need to do now is not complete reconciliation or dissolution, but rather choosing a perspective.

(Page 278)

In this book, Crum persistently questions the worldview of 'optimization' that has taken over the world.

And in the end, it boldly suggests that neither blind acceptance nor radical resistance is the answer, and that we should let go of the very language of 'optimization' that surrounds us.

For those who feel the need to put the brakes on the breathtakingly rapid pace of technological advancement and the relentless drive toward growth and development, "The Illusion of Optimization" will offer an intellectual pleasure, allowing them to concretize vague concerns through a variety of experiences and examples, and an opportunity to shift perspectives they'd never even considered breaking.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: April 9, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 304 pages | 456g | 140*210*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791171713981

- ISBN10: 1171713983

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)