Rousseau's Botany Lecture

|

Description

Book Introduction

A representative book has been published that allows us to confirm the side of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a well-known 18th-century French political philosopher, novelist, and educational theorist, as a 'plant lover' or 'plant observer'.

Rousseau's Botany Lectures consists of eight letters Rousseau sent to his close friend Madame Delécer between August 22, 1771, and April 11, 1773.

For those who are just beginning to take an interest in plants, he faithfully explains the history of plants and how to observe each part of them, while also confirming his genuine and sincere attitude toward plants.

Additionally, we can see how Rousseau's naturalistic educational philosophy, which calls for returning to nature and following its laws, can be implemented in everyday life.

The numerous detailed drawings and woodcut illustrations included in the book, combined with Rousseau's letters, create a lyrical atmosphere, increasing the book's collection value.

Rousseau's Botany Lectures consists of eight letters Rousseau sent to his close friend Madame Delécer between August 22, 1771, and April 11, 1773.

For those who are just beginning to take an interest in plants, he faithfully explains the history of plants and how to observe each part of them, while also confirming his genuine and sincere attitude toward plants.

Additionally, we can see how Rousseau's naturalistic educational philosophy, which calls for returning to nature and following its laws, can be implemented in everyday life.

The numerous detailed drawings and woodcut illustrations included in the book, combined with Rousseau's letters, create a lyrical atmosphere, increasing the book's collection value.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

Detailed image

Into the book

Dear friend, if I have explained it correctly, your wife will understand.

It is amazing how carefully nature has made provisions to ensure that pea embryos can safely mature, protected from harmful moisture, no matter how heavy the rain may be.

Nature does this without encasing the peas in hard shells.

If that were the case, the fruit would have been completely different from what we know now.

This supreme craftsman, always concerned about preserving all beings in the world, has taken such extreme care to protect plants from the diseases they may suffer as they bear fruit.

--- p.45

There are other, more precise and definitive characteristics that distinguish the masked corolla from the pure corolla.

Unlike the four seeds of the pure-flowered plant, which are exposed without an outer covering at the base of the calyx, the seeds of the masked-flowered plant are all enclosed in capsules.

So, only after they are fully ripe and the capsules open can the seeds be scattered.

Let me add a third feature here.

Most plants with pure flowers are fragrant.

--- p.57

Before we teach children the names of the plants in front of them, let's first teach them how to see them.

We must make this science a central part of our children's education.

Even though everything we call education has forgotten this.

This cannot be emphasized enough.

We must teach children not to be satisfied with words alone.

You have to make them believe that memorizing things is the same as not knowing anything.

--- p.61~62

“The plants that make up the family Umbelliferae are so numerous and so spontaneous that it is very difficult to distinguish between the lower genera.

Just like when brothers look so alike, it's easy to mistake who's who.

So people have come up with some principles that can help us make the distinction.

It's a pretty useful principle, but don't rely on it too much.

In both large and small inflorescences, the central part from which the radiating fleshy parts extend is not always exposed without a covering membrane.

Sometimes it is wrapped in small leaves like the ruffles on the sleeves.”

--- p.73~74

The point isn't to learn how to parrot the nomenclature of plants.

What you need to learn is the science of reality.

Let us learn about the science of reality, one of the most lovely disciplines we can cultivate.

--- p.77

We should not try to give botany too much importance to what it does not possess.

Botany is a discipline to be approached with genuine curiosity, for it has no practical utility beyond the wonders that thinking, sentient beings can derive from observing the wonders of nature and the universe.

Humans transform many things from their natural state to make them useful.

That in itself is not at all reprehensible.

But it is also true that because of this, humans often distort things and make the mistake of believing that they can study true nature in the works of their own hands.

These mistakes are especially common in civil society, but they also occur in gardens.

The double flowers in the flower beds that people admire so much are like monsters deprived of the ability to reproduce their own kind, which nature has endowed all living things with.

--- p.93

Because it would be of no use for me to send you dried plants.

To truly understand a plant, it's important to start by looking at it yourself.

Herbariums are used to remind us of what we already know.

If you haven't seen the plant before, you may end up with incorrect information.

So, if there is a plant you would like to know more about, you should collect it yourself and send it to me.

Then I can tell you the names of those plants, classify them, and explain them to you.

In time, your eyes and mind will become accustomed to forming concepts through comparison, and one day you will be able to classify, arrange, and name plants you see for the first time.

Only this science distinguishes a true botanist from a herbalist or a nomenclature expert.

It is amazing how carefully nature has made provisions to ensure that pea embryos can safely mature, protected from harmful moisture, no matter how heavy the rain may be.

Nature does this without encasing the peas in hard shells.

If that were the case, the fruit would have been completely different from what we know now.

This supreme craftsman, always concerned about preserving all beings in the world, has taken such extreme care to protect plants from the diseases they may suffer as they bear fruit.

--- p.45

There are other, more precise and definitive characteristics that distinguish the masked corolla from the pure corolla.

Unlike the four seeds of the pure-flowered plant, which are exposed without an outer covering at the base of the calyx, the seeds of the masked-flowered plant are all enclosed in capsules.

So, only after they are fully ripe and the capsules open can the seeds be scattered.

Let me add a third feature here.

Most plants with pure flowers are fragrant.

--- p.57

Before we teach children the names of the plants in front of them, let's first teach them how to see them.

We must make this science a central part of our children's education.

Even though everything we call education has forgotten this.

This cannot be emphasized enough.

We must teach children not to be satisfied with words alone.

You have to make them believe that memorizing things is the same as not knowing anything.

--- p.61~62

“The plants that make up the family Umbelliferae are so numerous and so spontaneous that it is very difficult to distinguish between the lower genera.

Just like when brothers look so alike, it's easy to mistake who's who.

So people have come up with some principles that can help us make the distinction.

It's a pretty useful principle, but don't rely on it too much.

In both large and small inflorescences, the central part from which the radiating fleshy parts extend is not always exposed without a covering membrane.

Sometimes it is wrapped in small leaves like the ruffles on the sleeves.”

--- p.73~74

The point isn't to learn how to parrot the nomenclature of plants.

What you need to learn is the science of reality.

Let us learn about the science of reality, one of the most lovely disciplines we can cultivate.

--- p.77

We should not try to give botany too much importance to what it does not possess.

Botany is a discipline to be approached with genuine curiosity, for it has no practical utility beyond the wonders that thinking, sentient beings can derive from observing the wonders of nature and the universe.

Humans transform many things from their natural state to make them useful.

That in itself is not at all reprehensible.

But it is also true that because of this, humans often distort things and make the mistake of believing that they can study true nature in the works of their own hands.

These mistakes are especially common in civil society, but they also occur in gardens.

The double flowers in the flower beds that people admire so much are like monsters deprived of the ability to reproduce their own kind, which nature has endowed all living things with.

--- p.93

Because it would be of no use for me to send you dried plants.

To truly understand a plant, it's important to start by looking at it yourself.

Herbariums are used to remind us of what we already know.

If you haven't seen the plant before, you may end up with incorrect information.

So, if there is a plant you would like to know more about, you should collect it yourself and send it to me.

Then I can tell you the names of those plants, classify them, and explain them to you.

In time, your eyes and mind will become accustomed to forming concepts through comparison, and one day you will be able to classify, arrange, and name plants you see for the first time.

Only this science distinguishes a true botanist from a herbalist or a nomenclature expert.

--- p.101~102

Publisher's Review

The only book that lets you meet the plant lover Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a well-known 18th-century French political philosopher, novelist, and educational theorist, has a small epithet that follows him around.

They are ‘plant lovers’ or ‘plant observers’.

It is difficult to hide his cautiousness, as he did not major in plants in earnest, and his only writings on plants were essays and letters rather than professional writings. However, his love for plants was clearly unique and extraordinary, and he was active in sharing the stories about plants that he had experienced and accumulated with those around him.

Some interpret this aspect of Rousseau's as an extension of his naturalistic educational philosophy that we must return to nature and follow its laws. However, in the recently published 『Rousseau's Botany Lectures』, we often see his pure and sincere attitude towards plants themselves.

“I love botany.

It's getting worse every day.

This book, filled with confessions like “I wonder if I’ll end up turning into a plant” (page 10), is the essence of Rousseau’s love of plants, one of his many facets.

We expect it to satisfy a wide range of audiences, from humanities readers who want to see how his philosophy naturally connects with and expands upon everyday life, to green enthusiasts just beginning to take an interest in plants.

“I believe that even someone who doesn’t know the names of any plants can become a great botanist.”

A beginner's guide to plants, from learning about plant structure to creating herbariums.

Rousseau's Botany Lectures consists of eight letters sent by Rousseau to his close friend Madame Delécer between August 22, 1771, and April 11, 1773.

In his letters, Rousseau, rather than revealing his side as a philosopher, closes the distance between himself and his wife by presenting himself as a “guide” who faithfully conveys the plant world with “a delightful and colorful subject” (p. 13).

Madame Delécerne is said to have taught her daughter Madelon about plants based on letters she received from Rousseau. This is also why the letters, rather than being filled with content for experts, faithfully served the role of explaining the history of plants and how to observe certain parts of them at the eye level of those who were just beginning to take an interest in plants.

Rousseau, who said that it would be enough to “prepare the patience to start from the very beginning” (p. 14), focuses on the ‘flowers’ centered around lilies and plants in the first letter, explaining them in the order of ‘corolla, ‘petals,’ ‘pistil,’ and ‘stamen.’

Then, up to the sixth letter, he sequentially introduces the six 'families' in the plant classification system (subordinate subject system) created by Linnaeus, and in the last eighth letter, he suggests making plant specimens himself, and suggests the process of making them in order.

Moreover, Rousseau's desire to become closer to plants shines through in his efforts to convey unfamiliar botanical concepts to the general public in an easy-to-understand manner using simple but precise sentences, in his logical way of describing them by restating the contents of a previously sent letter to provide an opportunity to review, in comparing and contrasting the structures of plants, and in grouping and explaining objects.

This book, along with 『Reveries of a Solitary Walker』, is considered to be Rousseau's last work, and caused a great stir in Europe when it was published in the early 19th century.

Even though 200 years have passed since then, the book has been republished repeatedly in France and has reached this point because the letter's focus is on beginners in plants.

Also, it is probably because the fact that plants are always ready to welcome us when we look around remains unchanged regardless of the times.

“Be patient and read only what is contained in the book of nature.”

Learning the Wisdom and Virtue of Nature and Botany with Rousseau

Rousseau's deep love for plants actually stemmed from a trivial and chance encounter.

It all started in the late summer of 1735, when he was captivated by a blue 'vinca' flower that bloomed out of season on a roadside in Charmette, France.

Although botany was a relatively 'non-mainstream' discipline at the time, Rousseau gave botany a higher status than other disciplines and concretized his own perspective.

He emphasized that rather than simply admiring the beauty of flowers or learning their names (naming), one should read the book called 'Nature' and directly observe the structure of flowers and the organs that compose them, rather than relying on books or materials (“If you study general nomenclature through books, you will know many names of plants, but you will gain little understanding of plants.

The knowledge thus gained will soon become blurred, (omitted) and eventually no understanding other than the name will remain” (p. 38).

He was also wary of horticultural plants and focused on 'wild plants', and maintained a 'nativist' stance, being interested in the hay at his feet rather than plants from across the sea ("If it's a double flower that has been improved, you don't have to bother researching it.

These are ugly, deformed flowers.

It could also be said that it is a flower that has been decorated to suit people's fashion.

In such places, nature no longer exists” (p. 25).

Of course, just before he passed away, he embarked on a project to create a herbarium encompassing all the plants on Earth, and he organized 494 specimens according to Linnaeus' classification system into 15 hardboard binders. However, he was consistent in his fundamental stance that botany was the best discipline to learn 'wisdom' and 'virtue'.

For example, we can cite these parts:

Furthermore, he even said that nature is the best object for us to ‘meditate’ (“If there is nothing more valuable than nature among the objects of our meditation, what good would it be if we could fill our souls with it?” (p. 13)).

This can be repeatedly confirmed in Rousseau's attitude of not objectifying or hastily approaching plants throughout his letters.

Moreover, as Marc Janson, former director of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, who wrote the preface to this book, pointed out, in the current situation where we are faced with the threat of climate crisis, deforestation, and loss of plant species, “the work of observing and describing plants, naming plants, and collecting plants in the form of herbariums or seed banks, which Rousseau emphasized, has become more important than ever” (p. 9). The message that accurately understanding the current state of the plant world is the top priority in order to prepare for the future of the Earth can also be said to be another wisdom and teaching that botany awakens us to.

Rousseau's Botanical Letters, read with accurate and colorful illustrations

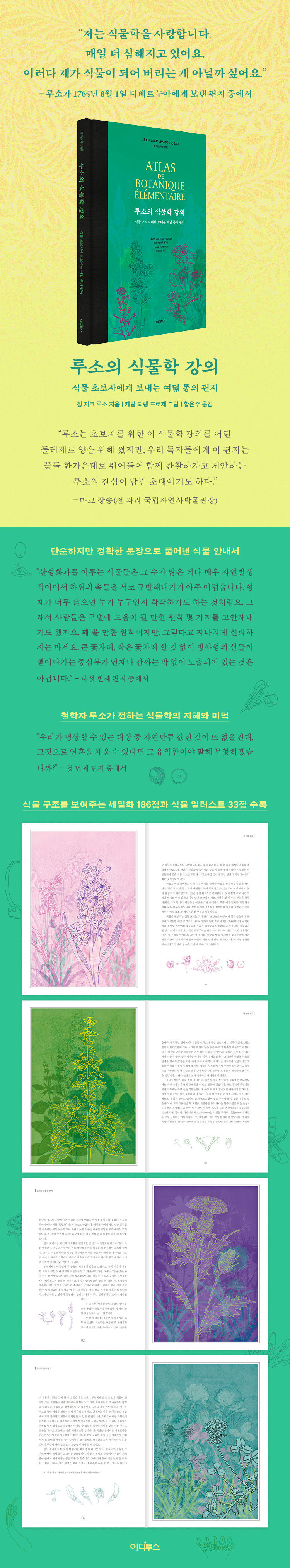

One of the important virtues of 『Rousseau's Botany Lectures』 can be found in the illustrations that capture the reader's attention the moment the book is opened.

This book is one of the 'Atlas Series' published by Artaud in France, which has achieved success by combining botany and illustration. The illustrator, Karin D'Orin-Froget, has been in charge of several volumes in the series.

Prose draws on Rousseau's efforts to not only accurately describe the plant structure but also to see the plant as a whole, and simultaneously depicts these plants in detail and in print.

In addition, by utilizing bright and colorful colors throughout, the illustration and the format of the 'letter' come together to create a lyrical atmosphere and help increase the collection value.

This book, a collaboration between an 1800s philosopher and a 2020s illustrator, demonstrates the timeless value of classics and the infinite ways to express the diverse nature.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a well-known 18th-century French political philosopher, novelist, and educational theorist, has a small epithet that follows him around.

They are ‘plant lovers’ or ‘plant observers’.

It is difficult to hide his cautiousness, as he did not major in plants in earnest, and his only writings on plants were essays and letters rather than professional writings. However, his love for plants was clearly unique and extraordinary, and he was active in sharing the stories about plants that he had experienced and accumulated with those around him.

Some interpret this aspect of Rousseau's as an extension of his naturalistic educational philosophy that we must return to nature and follow its laws. However, in the recently published 『Rousseau's Botany Lectures』, we often see his pure and sincere attitude towards plants themselves.

“I love botany.

It's getting worse every day.

This book, filled with confessions like “I wonder if I’ll end up turning into a plant” (page 10), is the essence of Rousseau’s love of plants, one of his many facets.

We expect it to satisfy a wide range of audiences, from humanities readers who want to see how his philosophy naturally connects with and expands upon everyday life, to green enthusiasts just beginning to take an interest in plants.

“I believe that even someone who doesn’t know the names of any plants can become a great botanist.”

A beginner's guide to plants, from learning about plant structure to creating herbariums.

Rousseau's Botany Lectures consists of eight letters sent by Rousseau to his close friend Madame Delécer between August 22, 1771, and April 11, 1773.

In his letters, Rousseau, rather than revealing his side as a philosopher, closes the distance between himself and his wife by presenting himself as a “guide” who faithfully conveys the plant world with “a delightful and colorful subject” (p. 13).

Madame Delécerne is said to have taught her daughter Madelon about plants based on letters she received from Rousseau. This is also why the letters, rather than being filled with content for experts, faithfully served the role of explaining the history of plants and how to observe certain parts of them at the eye level of those who were just beginning to take an interest in plants.

Rousseau, who said that it would be enough to “prepare the patience to start from the very beginning” (p. 14), focuses on the ‘flowers’ centered around lilies and plants in the first letter, explaining them in the order of ‘corolla, ‘petals,’ ‘pistil,’ and ‘stamen.’

Then, up to the sixth letter, he sequentially introduces the six 'families' in the plant classification system (subordinate subject system) created by Linnaeus, and in the last eighth letter, he suggests making plant specimens himself, and suggests the process of making them in order.

Moreover, Rousseau's desire to become closer to plants shines through in his efforts to convey unfamiliar botanical concepts to the general public in an easy-to-understand manner using simple but precise sentences, in his logical way of describing them by restating the contents of a previously sent letter to provide an opportunity to review, in comparing and contrasting the structures of plants, and in grouping and explaining objects.

This book, along with 『Reveries of a Solitary Walker』, is considered to be Rousseau's last work, and caused a great stir in Europe when it was published in the early 19th century.

Even though 200 years have passed since then, the book has been republished repeatedly in France and has reached this point because the letter's focus is on beginners in plants.

Also, it is probably because the fact that plants are always ready to welcome us when we look around remains unchanged regardless of the times.

“Be patient and read only what is contained in the book of nature.”

Learning the Wisdom and Virtue of Nature and Botany with Rousseau

Rousseau's deep love for plants actually stemmed from a trivial and chance encounter.

It all started in the late summer of 1735, when he was captivated by a blue 'vinca' flower that bloomed out of season on a roadside in Charmette, France.

Although botany was a relatively 'non-mainstream' discipline at the time, Rousseau gave botany a higher status than other disciplines and concretized his own perspective.

He emphasized that rather than simply admiring the beauty of flowers or learning their names (naming), one should read the book called 'Nature' and directly observe the structure of flowers and the organs that compose them, rather than relying on books or materials (“If you study general nomenclature through books, you will know many names of plants, but you will gain little understanding of plants.

The knowledge thus gained will soon become blurred, (omitted) and eventually no understanding other than the name will remain” (p. 38).

He was also wary of horticultural plants and focused on 'wild plants', and maintained a 'nativist' stance, being interested in the hay at his feet rather than plants from across the sea ("If it's a double flower that has been improved, you don't have to bother researching it.

These are ugly, deformed flowers.

It could also be said that it is a flower that has been decorated to suit people's fashion.

In such places, nature no longer exists” (p. 25).

Of course, just before he passed away, he embarked on a project to create a herbarium encompassing all the plants on Earth, and he organized 494 specimens according to Linnaeus' classification system into 15 hardboard binders. However, he was consistent in his fundamental stance that botany was the best discipline to learn 'wisdom' and 'virtue'.

For example, we can cite these parts:

Furthermore, he even said that nature is the best object for us to ‘meditate’ (“If there is nothing more valuable than nature among the objects of our meditation, what good would it be if we could fill our souls with it?” (p. 13)).

This can be repeatedly confirmed in Rousseau's attitude of not objectifying or hastily approaching plants throughout his letters.

Moreover, as Marc Janson, former director of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, who wrote the preface to this book, pointed out, in the current situation where we are faced with the threat of climate crisis, deforestation, and loss of plant species, “the work of observing and describing plants, naming plants, and collecting plants in the form of herbariums or seed banks, which Rousseau emphasized, has become more important than ever” (p. 9). The message that accurately understanding the current state of the plant world is the top priority in order to prepare for the future of the Earth can also be said to be another wisdom and teaching that botany awakens us to.

Rousseau's Botanical Letters, read with accurate and colorful illustrations

One of the important virtues of 『Rousseau's Botany Lectures』 can be found in the illustrations that capture the reader's attention the moment the book is opened.

This book is one of the 'Atlas Series' published by Artaud in France, which has achieved success by combining botany and illustration. The illustrator, Karin D'Orin-Froget, has been in charge of several volumes in the series.

Prose draws on Rousseau's efforts to not only accurately describe the plant structure but also to see the plant as a whole, and simultaneously depicts these plants in detail and in print.

In addition, by utilizing bright and colorful colors throughout, the illustration and the format of the 'letter' come together to create a lyrical atmosphere and help increase the collection value.

This book, a collaboration between an 1800s philosopher and a 2020s illustrator, demonstrates the timeless value of classics and the infinite ways to express the diverse nature.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: March 7, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 124 pages | 562g | 185*260*15mm

- ISBN13: 9791191535105

- ISBN10: 119153510X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)