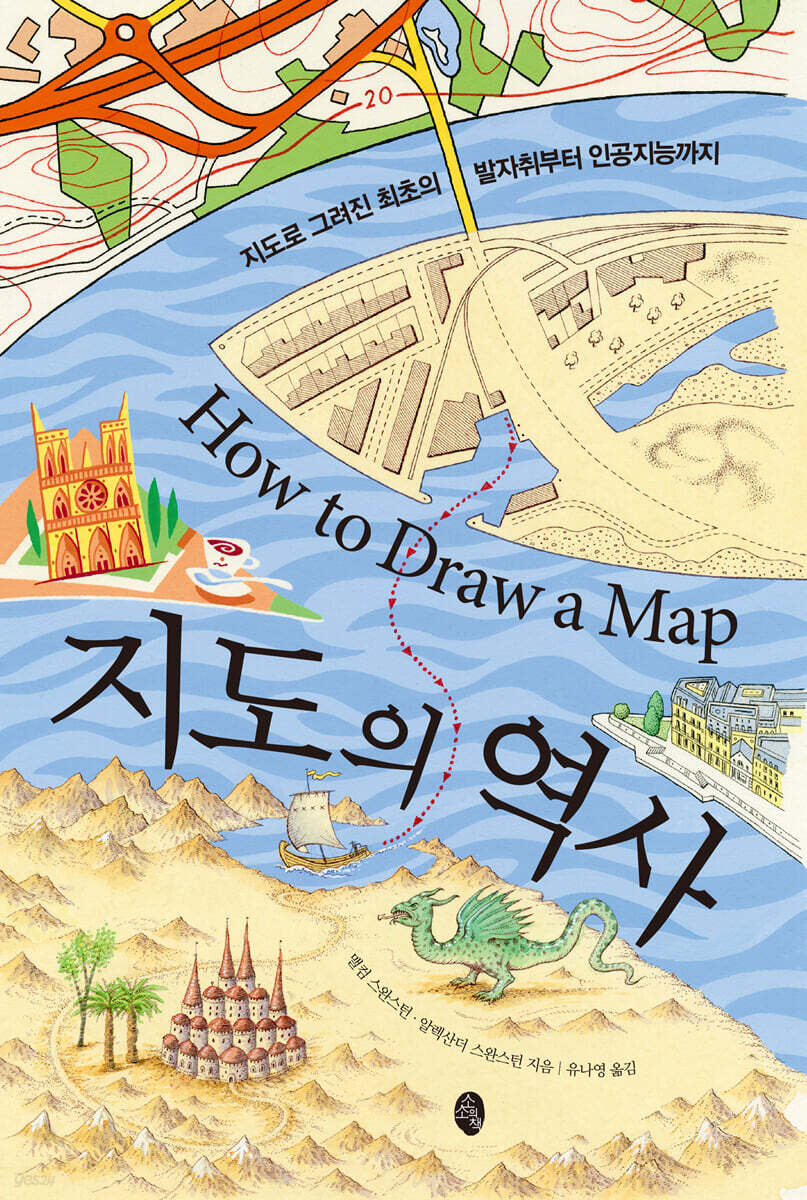

History of Maps

|

Description

Book Introduction

What history is contained in the map?

A fascinating journey of a cartographer creating a visual history of the Earth.

This book perfectly recreates 65 maps, from the earliest known world map to originals of historically significant thematic maps and aerial photographs.

Ancient people, who developed the concept of time by reading the changes of seasons through the movements of the sun, moon, and celestial bodies, created maps to understand the world and environment around them.

Since then, maps have played a crucial role in the development of human civilization, including religion, exploration and migration to discover new lands, expansion of trade, war, and division of territory.

In particular, advancements in science and technology have enabled the creation of much more diverse and precise maps than before.

This book vividly tells the story of the cartographers who went through endless challenges and research to create the maps we know today.

A fascinating journey of a cartographer creating a visual history of the Earth.

This book perfectly recreates 65 maps, from the earliest known world map to originals of historically significant thematic maps and aerial photographs.

Ancient people, who developed the concept of time by reading the changes of seasons through the movements of the sun, moon, and celestial bodies, created maps to understand the world and environment around them.

Since then, maps have played a crucial role in the development of human civilization, including religion, exploration and migration to discover new lands, expansion of trade, war, and division of territory.

In particular, advancements in science and technology have enabled the creation of much more diverse and precise maps than before.

This book vividly tells the story of the cartographers who went through endless challenges and research to create the maps we know today.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

ㆍPreface

1 Human footprints drawn on the map

2 When the sun shines on the well of Syene

3. The Legacy of Rome

4 The Road to Paradise

5 Discovering a New World

6 We came first

7 The first circumnavigation of the world

8 Explore every corner of the world

9 Mercator's chart

10 Land of the South

11 Slave Trade

12 Scientific Measurement

13 The Problem of the Empire

14 Longitude and Latitude

15 Territorial Disputes

World War 16

17 Narratives of City Maps

18 To a higher place

ㆍThank you

Translator's Note

1 Human footprints drawn on the map

2 When the sun shines on the well of Syene

3. The Legacy of Rome

4 The Road to Paradise

5 Discovering a New World

6 We came first

7 The first circumnavigation of the world

8 Explore every corner of the world

9 Mercator's chart

10 Land of the South

11 Slave Trade

12 Scientific Measurement

13 The Problem of the Empire

14 Longitude and Latitude

15 Territorial Disputes

World War 16

17 Narratives of City Maps

18 To a higher place

ㆍThank you

Translator's Note

Detailed image

Into the book

Ptolemy divided the Earth's circumference into 360 degrees (based on the Babylonian sexagesimal system), and each degree was divided into 60 minutes, estimating that each degree was 500 stadia (2,700 kilometers).

Although he estimated the size of the Earth to be smaller than Eratosthenes' calculations, he estimated the habitable area of the Earth to be larger than the common belief of people of his time.

This territory stretched from the Isle of Lucky in the west to Cattigara, presumed to be somewhere in present-day Vietnam, in the east, and from Thule, located at 63 degrees north latitude, to Agisymba in sub-Saharan Africa, located at 16 degrees south latitude.

The edges of the world described by Ptolemy were based on hypotheses, legends, and conjectures.

For example, he believed that there was a large, unknown continent in the Southern Hemisphere to balance out Europe and Asia in the Northern Hemisphere.

It was also believed that the Indian Ocean was surrounded by Africa, and that Africa extended eastward to meet Asia.

The latter belief was reflected in Ptolemy's maps even after the Portuguese sailed around Africa and into the Indian Ocean.

--- From "3. The Legacy of Rome"

1569 saw the publication of Mercator's most famous map, Nova et aucta orbis terrae descriptio ad usum navigantium emendate accommodata (A New and More Complete Representation of the Earth Adapted for Navigation).

Until then, most European cartographers and explorers had relied on ellipsoidal maps derived from Ptolemy's grid of parallels and meridians.

This map showed all the 1-degree intervals between parallels and meridians as the same width, which meant that the straight line that navigators draw on the map along a given compass bearing—the rhumb line—was drawn as a curve and had to be recalculated each time they moved.

Mercator realized that by increasing the spacing between parallels as one moves north or south from the equator, so that the angle between parallels and meridians is always 90 degrees, the navigator's course can be kept straight, thus eliminating the need for frequent recalculation.

Looking at a map gives you a rough idea of how the Mercator projection works.

--- From "9. Mercator's Chart"

In 1738, King George II called both sides of this troubled colony to a truce.

This precarious situation was somewhat resolved in 1760 when the Calvert and Penn families accepted the judgment of the English Lord Chancellor in 1750.

A new boundary line was drawn westward from a point 15 miles south of Philadelphia, and a north-south boundary in Delaware was also agreed upon.

But while drawing the line in London was easy, marking it on land covered with dense forests, wide rivers, and swamps was a completely different matter.

I tried several local surveyors, but was dissatisfied with both Calvert's and Penn's camps.

Ultimately, they consulted the Royal Astronomical Observatory in London as a neutral and accurate arbiter.

The President of the Royal Society nominated two people for this position.

Charles Mason from Gloucestershire in southwest England and Jeremiah Dixon from County Durham in northeast England.

--- From “14. Longitude and Latitude”

In the 19th century, London's population grew rapidly—not only as the capital of a nation but also as the center of a global empire.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 attracted six million tourists from across the British Empire and the world.

The subway network was developed starting in 1863.

The world's first wooden carriages with gas lighting were pulled by a steam locomotive and operated between Paddington and Farringdon.

Carrying 38,000 passengers on its first day of operation, the route was hailed as a great success.

And after 50 years of expansion, perhaps the most recognizable graphic map on the planet was born.

This famous map was a revolutionary development, becoming the standard for Underground maps, replacing previous maps that attempted to reflect the actual geography of Greater London and its Underground routes.

The original designer of this now iconic 'Tube map' was Henry Charles Beck, an electrical draftsman for the London Underground signalling department, now better known as Harry Beck.

You can see that his ideas were influenced by electrical wiring diagrams.

The early subway route plans followed a strict geographical layout, which was not easy to understand.

However, Harry Beck's new map soon became popular and influenced subway and other route maps around the world.

Although he estimated the size of the Earth to be smaller than Eratosthenes' calculations, he estimated the habitable area of the Earth to be larger than the common belief of people of his time.

This territory stretched from the Isle of Lucky in the west to Cattigara, presumed to be somewhere in present-day Vietnam, in the east, and from Thule, located at 63 degrees north latitude, to Agisymba in sub-Saharan Africa, located at 16 degrees south latitude.

The edges of the world described by Ptolemy were based on hypotheses, legends, and conjectures.

For example, he believed that there was a large, unknown continent in the Southern Hemisphere to balance out Europe and Asia in the Northern Hemisphere.

It was also believed that the Indian Ocean was surrounded by Africa, and that Africa extended eastward to meet Asia.

The latter belief was reflected in Ptolemy's maps even after the Portuguese sailed around Africa and into the Indian Ocean.

--- From "3. The Legacy of Rome"

1569 saw the publication of Mercator's most famous map, Nova et aucta orbis terrae descriptio ad usum navigantium emendate accommodata (A New and More Complete Representation of the Earth Adapted for Navigation).

Until then, most European cartographers and explorers had relied on ellipsoidal maps derived from Ptolemy's grid of parallels and meridians.

This map showed all the 1-degree intervals between parallels and meridians as the same width, which meant that the straight line that navigators draw on the map along a given compass bearing—the rhumb line—was drawn as a curve and had to be recalculated each time they moved.

Mercator realized that by increasing the spacing between parallels as one moves north or south from the equator, so that the angle between parallels and meridians is always 90 degrees, the navigator's course can be kept straight, thus eliminating the need for frequent recalculation.

Looking at a map gives you a rough idea of how the Mercator projection works.

--- From "9. Mercator's Chart"

In 1738, King George II called both sides of this troubled colony to a truce.

This precarious situation was somewhat resolved in 1760 when the Calvert and Penn families accepted the judgment of the English Lord Chancellor in 1750.

A new boundary line was drawn westward from a point 15 miles south of Philadelphia, and a north-south boundary in Delaware was also agreed upon.

But while drawing the line in London was easy, marking it on land covered with dense forests, wide rivers, and swamps was a completely different matter.

I tried several local surveyors, but was dissatisfied with both Calvert's and Penn's camps.

Ultimately, they consulted the Royal Astronomical Observatory in London as a neutral and accurate arbiter.

The President of the Royal Society nominated two people for this position.

Charles Mason from Gloucestershire in southwest England and Jeremiah Dixon from County Durham in northeast England.

--- From “14. Longitude and Latitude”

In the 19th century, London's population grew rapidly—not only as the capital of a nation but also as the center of a global empire.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 attracted six million tourists from across the British Empire and the world.

The subway network was developed starting in 1863.

The world's first wooden carriages with gas lighting were pulled by a steam locomotive and operated between Paddington and Farringdon.

Carrying 38,000 passengers on its first day of operation, the route was hailed as a great success.

And after 50 years of expansion, perhaps the most recognizable graphic map on the planet was born.

This famous map was a revolutionary development, becoming the standard for Underground maps, replacing previous maps that attempted to reflect the actual geography of Greater London and its Underground routes.

The original designer of this now iconic 'Tube map' was Henry Charles Beck, an electrical draftsman for the London Underground signalling department, now better known as Harry Beck.

You can see that his ideas were influenced by electrical wiring diagrams.

The early subway route plans followed a strict geographical layout, which was not easy to understand.

However, Harry Beck's new map soon became popular and influenced subway and other route maps around the world.

--- From "17ㆍNarrative of City Maps"

Publisher's Review

How should we read and accept maps, the starting point for understanding the world?

A history of mapmaking that broadly encompasses diverse information, knowledge, and contemporary worldviews.

In 1881, an archaeologist discovered a fragment of a clay tablet inscribed with cuneiform script west of Baghdad, once part of the Ottoman Empire.

It was the oldest world map, looking straight down at the world from above.

The space between the two concentric circles is the salt sea surrounding the world, within which lies the 'known world', and a symbol interpreted as the Euphrates River flows through this 'world'.

Around the river, major cities and centers are marked, along with symbols indicating mountains, swamps, and canals.

In this world map created in the 6th century BC, the Babylonians divided the circle into 360 equal parts and defined the length of a year as approximately 360 days.

These calculation methods are still useful today and play an important role in map making.

This book tells the story of mapmakers who tirelessly explored and realistically expressed the world we live in, and who, despite all the adversity and hardship, tirelessly sought to fill in the unknown gaps.

We will also examine the process from the first world maps created by ancient people to the completion of today's world maps through scientific surveying using cutting-edge equipment, and consider the future of mapmaking.

This book, based on the rich insight and knowledge of a cartographer who has been making maps for over 50 years and has created over 100 volumes of various field histories and the largest number of thematic maps in history, contains the historical stories each map tells while the authors personally recreate 65 carefully selected maps from among tens of thousands of examples.

This book first examines the research that ancient people conducted to understand the world and what their achievements were.

Anaximander, believed to be a disciple of Thales, believed that the world was cylindrical, floating in the middle of 'infinity'.

His world map thus evokes the Babylonian notion that the upper surface, habitable for human beings, was surrounded by a ring-shaped ocean.

Eratosthenes, a multi-disciplinary ancient Greek, measured the size of the Earth, established some of the basic rules of mapmaking, and taught many later cartographers the importance of astronomy.

Ptolemy's maps and writings, which were the first to use latitudes and longitudes and to specify the locations of places through astronomical observations, not only imposed geometric order on the world but also had a lasting influence, lasting long after the Renaissance.

In particular, his monumental work, Geography, would define mapmaking in the West for the next 2,000 years.

In the Middle Ages, 'Christian geography' became dominant, and various forms of mappa mundi were handed down, including the territorial map, the TO map (a three-part map), the Beatus map (a four-part map), and the composite map (the Great Map).

The most famous of these is the Hereford Mappa Mundi (made around 1300), which depicts fifteen biblical events, five scenes from ancient mythology, 420 cities and towns, and people, animals, and plants on a single, massive sheet of vellum.

Meanwhile, the representative of Islamic cartography is Al-Masoudi.

His world map viewed the world with the south facing upward, following the Arab tradition of the time.

And Al-Idrasi's maps, which combined Islamic and Christian geographical traditions, became the standard for accuracy for nearly 300 years after they were produced.

In the section covering the story of the Age of Exploration, we look into the paths taken by Vasco da Gama, Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, and others to explore the oceans and the New World, open trade routes, and establish settlements, as well as how the 'Mercator' projection, the most famous in history, was created and why it is used by all navigators.

In addition, the story of the discovery of Australia by European explorers including James Cook, the slave trade, and the Cassini family, who laid the foundation for mapmaking in each country by applying accurate information and triangulation techniques to create the maps we are familiar with today, and by establishing standards for systematic mapmaking, is also very interesting.

World history on the map, meet that decisive moment!

A book that meticulously examines everything from the worldview of ancient people to the historical facts contained in each theme.

As new lands were discovered, the scramble for colonies among European powers, including Britain, France, Spain, and Portugal, who sought to expand their empires across the globe, became more intense.

As surveys of national territories and colonies were conducted in various places and joint surveys between countries began, the need for more precise maps increased.

One such example is the Great Triangulation Survey across India.

This extensive survey, which lasted from 1802 to 1871, gave the British administration a bird's eye view of the territory within the Indian subcontinent.

Sometimes a single line on a map can have a huge impact.

After 1763, as the number of settlers from the British Isles to Britain's North American colonies increased rapidly, land disputes began to arise in the colonies due to inaccurate maps based on land previously granted by the British government.

There is one famous boundary line that has been drawn to address this situation.

This is the Mason-Dixon Line, a line surveyed in colonial America that not only resolved territorial disputes between Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, but also created a cultural boundary.

It became a cultural dividing line between North and South, free and slave, rebel and Union.

The role of leadership in war is more important than anything else.

Because it is an essential element not only for assessing the situation but also for executing strategy and tactics.

Armed with the religious belief of holy violence, this book maps the movements of the Four Crusades, the major battles of the American Civil War that left a terrible scar on the memory of all Americans, and the operational plans and bridgehead battles of World War I that brought about the end of four empires: Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Imperial Russia.

Additionally, the outlines of the war are examined through four battles in World War II: the Battle of Britain, Operation Barbarossa, the Battle of Midway, and Operation Overlord.

The book also tells the urban history of London, Paris, and New York.

It also shows maps that narratively express each city, such as the map of Harry Beck, who designed the first London Underground map and influenced subway and other route maps around the world; the formation of the Paris Commune, a revolutionary self-governing government established through an uprising of citizens and workers; and the appearance of New York, which has preserved its former form to this day.

The author, a cartographer, visits various places in this book, shows various thematic maps related to them, and meticulously adds historical events. In this journey, he points to the development of aerial photography in the early 20th century as the most dramatic change in mapmaking.

Unlike the past, when countless surveyors and cartographers were dispatched to survey the landscape on foot to prepare base maps, a single high-resolution camera and an aerial mission can now document thousands of square miles.

Accordingly, mapmakers who recreate human history face endless challenges, and in the future, artificial intelligence will be able to create and continuously update maps of global events such as migration, population growth, and climate change based on statistics.

Yet, I remain convinced that maps still reflect our ability to understand and relate to the world around us, and that mapmaking plays a special role in understanding our past and pointing the way forward for the future.

A history of mapmaking that broadly encompasses diverse information, knowledge, and contemporary worldviews.

In 1881, an archaeologist discovered a fragment of a clay tablet inscribed with cuneiform script west of Baghdad, once part of the Ottoman Empire.

It was the oldest world map, looking straight down at the world from above.

The space between the two concentric circles is the salt sea surrounding the world, within which lies the 'known world', and a symbol interpreted as the Euphrates River flows through this 'world'.

Around the river, major cities and centers are marked, along with symbols indicating mountains, swamps, and canals.

In this world map created in the 6th century BC, the Babylonians divided the circle into 360 equal parts and defined the length of a year as approximately 360 days.

These calculation methods are still useful today and play an important role in map making.

This book tells the story of mapmakers who tirelessly explored and realistically expressed the world we live in, and who, despite all the adversity and hardship, tirelessly sought to fill in the unknown gaps.

We will also examine the process from the first world maps created by ancient people to the completion of today's world maps through scientific surveying using cutting-edge equipment, and consider the future of mapmaking.

This book, based on the rich insight and knowledge of a cartographer who has been making maps for over 50 years and has created over 100 volumes of various field histories and the largest number of thematic maps in history, contains the historical stories each map tells while the authors personally recreate 65 carefully selected maps from among tens of thousands of examples.

This book first examines the research that ancient people conducted to understand the world and what their achievements were.

Anaximander, believed to be a disciple of Thales, believed that the world was cylindrical, floating in the middle of 'infinity'.

His world map thus evokes the Babylonian notion that the upper surface, habitable for human beings, was surrounded by a ring-shaped ocean.

Eratosthenes, a multi-disciplinary ancient Greek, measured the size of the Earth, established some of the basic rules of mapmaking, and taught many later cartographers the importance of astronomy.

Ptolemy's maps and writings, which were the first to use latitudes and longitudes and to specify the locations of places through astronomical observations, not only imposed geometric order on the world but also had a lasting influence, lasting long after the Renaissance.

In particular, his monumental work, Geography, would define mapmaking in the West for the next 2,000 years.

In the Middle Ages, 'Christian geography' became dominant, and various forms of mappa mundi were handed down, including the territorial map, the TO map (a three-part map), the Beatus map (a four-part map), and the composite map (the Great Map).

The most famous of these is the Hereford Mappa Mundi (made around 1300), which depicts fifteen biblical events, five scenes from ancient mythology, 420 cities and towns, and people, animals, and plants on a single, massive sheet of vellum.

Meanwhile, the representative of Islamic cartography is Al-Masoudi.

His world map viewed the world with the south facing upward, following the Arab tradition of the time.

And Al-Idrasi's maps, which combined Islamic and Christian geographical traditions, became the standard for accuracy for nearly 300 years after they were produced.

In the section covering the story of the Age of Exploration, we look into the paths taken by Vasco da Gama, Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, and others to explore the oceans and the New World, open trade routes, and establish settlements, as well as how the 'Mercator' projection, the most famous in history, was created and why it is used by all navigators.

In addition, the story of the discovery of Australia by European explorers including James Cook, the slave trade, and the Cassini family, who laid the foundation for mapmaking in each country by applying accurate information and triangulation techniques to create the maps we are familiar with today, and by establishing standards for systematic mapmaking, is also very interesting.

World history on the map, meet that decisive moment!

A book that meticulously examines everything from the worldview of ancient people to the historical facts contained in each theme.

As new lands were discovered, the scramble for colonies among European powers, including Britain, France, Spain, and Portugal, who sought to expand their empires across the globe, became more intense.

As surveys of national territories and colonies were conducted in various places and joint surveys between countries began, the need for more precise maps increased.

One such example is the Great Triangulation Survey across India.

This extensive survey, which lasted from 1802 to 1871, gave the British administration a bird's eye view of the territory within the Indian subcontinent.

Sometimes a single line on a map can have a huge impact.

After 1763, as the number of settlers from the British Isles to Britain's North American colonies increased rapidly, land disputes began to arise in the colonies due to inaccurate maps based on land previously granted by the British government.

There is one famous boundary line that has been drawn to address this situation.

This is the Mason-Dixon Line, a line surveyed in colonial America that not only resolved territorial disputes between Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, but also created a cultural boundary.

It became a cultural dividing line between North and South, free and slave, rebel and Union.

The role of leadership in war is more important than anything else.

Because it is an essential element not only for assessing the situation but also for executing strategy and tactics.

Armed with the religious belief of holy violence, this book maps the movements of the Four Crusades, the major battles of the American Civil War that left a terrible scar on the memory of all Americans, and the operational plans and bridgehead battles of World War I that brought about the end of four empires: Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Imperial Russia.

Additionally, the outlines of the war are examined through four battles in World War II: the Battle of Britain, Operation Barbarossa, the Battle of Midway, and Operation Overlord.

The book also tells the urban history of London, Paris, and New York.

It also shows maps that narratively express each city, such as the map of Harry Beck, who designed the first London Underground map and influenced subway and other route maps around the world; the formation of the Paris Commune, a revolutionary self-governing government established through an uprising of citizens and workers; and the appearance of New York, which has preserved its former form to this day.

The author, a cartographer, visits various places in this book, shows various thematic maps related to them, and meticulously adds historical events. In this journey, he points to the development of aerial photography in the early 20th century as the most dramatic change in mapmaking.

Unlike the past, when countless surveyors and cartographers were dispatched to survey the landscape on foot to prepare base maps, a single high-resolution camera and an aerial mission can now document thousands of square miles.

Accordingly, mapmakers who recreate human history face endless challenges, and in the future, artificial intelligence will be able to create and continuously update maps of global events such as migration, population growth, and climate change based on statistics.

Yet, I remain convinced that maps still reflect our ability to understand and relate to the world around us, and that mapmaking plays a special role in understanding our past and pointing the way forward for the future.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: October 18, 2021

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 288 pages | 638g | 150*225*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791188941681

- ISBN10: 1188941682

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)