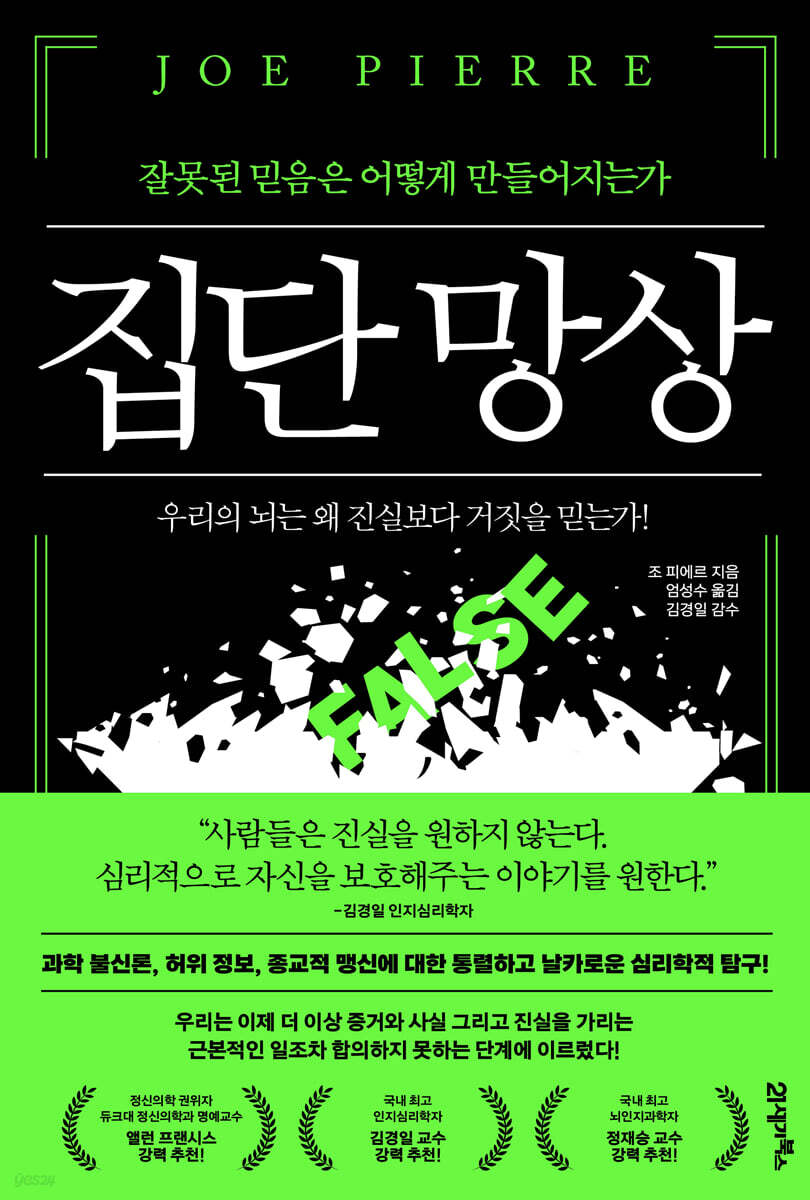

collective delusion

|

Description

Book Introduction

★ Highly recommended by Professors Kim Kyung-il and Jeong Jae-seung! ★

★ Professor Joe Pierre's first book has been highlighted by leading media outlets such as the New York Times, The Guardian, CNN, and the BBC!

An era of extreme distrust, with nations and societies around the world divided over "what to believe"!

Where do the false beliefs that divide our society originate?

In September 2025, Charlie Kirk, a conservative youth activist and leading far-right politician, was shot and killed during a speech in Utah, USA.

He, who had been hurling hateful and discriminatory language at American society, eventually became the target of that language and lost his life to extreme violence.

Beyond a personal tragedy, this incident starkly exposes the perilous state of a society where hate, conspiracy theories, and political extremism are commonplace.

In an age where truth is obscured by distrust, anger is mistaken for a legitimate means, and the logic of "eliminating the enemy" leads to action.

We must now ask:

How can we stop this politics of catastrophe, and how can we restore the language of truth and trust?

Professor Joe Pierre, who has long studied mental illnesses such as amnesia and schizophrenia, diagnoses that the world is now “destructing itself due to false beliefs.”

A society of extreme distrust where “all sorts of misinformation and conspiracy theories are accepted as truth, scientific inquiry is distorted into political debate, and even self-evident facts and truths are questioned.”

Indeed, democracy is in grave danger because of individual beliefs.

South Korea is no exception.

They do not hesitate to stereotype, or even demonize, the opposing camp.

Bipartisan cooperation is virtually extinct.

Because political beliefs are part of our 'social self,' attacks on our political views are immediately perceived as 'attacks on myself.'

As the author points out, “we now value sticking to what we believe more than considering alternative perspectives or revising our views based on new information.”

The author points out that false beliefs do not stem from class or political factors.

Tracing back our misconceptions, we eventually arrive at “the crucial starting point: our brain.”

This book will give you a glimpse into the chaos of this world: how the brain interacts with the world, how we develop conflicting beliefs, and how we vehemently defend “beliefs that are not worth defending,” ultimately reaching the point of taking someone’s life.

The author emphasizes:

Anyone can be an extreme ideologue, and understanding, tolerance, and compassion begin with recognizing that those with flawed beliefs are imperfect human beings, rather than stereotyping them.

That may be the attitude that humanity needs to take to solve the problem together in the face of a global crisis.

This is precisely why this book is not simply an ethical cry, but an intellectual journey born of cognitive empathy.

★ Professor Joe Pierre's first book has been highlighted by leading media outlets such as the New York Times, The Guardian, CNN, and the BBC!

An era of extreme distrust, with nations and societies around the world divided over "what to believe"!

Where do the false beliefs that divide our society originate?

In September 2025, Charlie Kirk, a conservative youth activist and leading far-right politician, was shot and killed during a speech in Utah, USA.

He, who had been hurling hateful and discriminatory language at American society, eventually became the target of that language and lost his life to extreme violence.

Beyond a personal tragedy, this incident starkly exposes the perilous state of a society where hate, conspiracy theories, and political extremism are commonplace.

In an age where truth is obscured by distrust, anger is mistaken for a legitimate means, and the logic of "eliminating the enemy" leads to action.

We must now ask:

How can we stop this politics of catastrophe, and how can we restore the language of truth and trust?

Professor Joe Pierre, who has long studied mental illnesses such as amnesia and schizophrenia, diagnoses that the world is now “destructing itself due to false beliefs.”

A society of extreme distrust where “all sorts of misinformation and conspiracy theories are accepted as truth, scientific inquiry is distorted into political debate, and even self-evident facts and truths are questioned.”

Indeed, democracy is in grave danger because of individual beliefs.

South Korea is no exception.

They do not hesitate to stereotype, or even demonize, the opposing camp.

Bipartisan cooperation is virtually extinct.

Because political beliefs are part of our 'social self,' attacks on our political views are immediately perceived as 'attacks on myself.'

As the author points out, “we now value sticking to what we believe more than considering alternative perspectives or revising our views based on new information.”

The author points out that false beliefs do not stem from class or political factors.

Tracing back our misconceptions, we eventually arrive at “the crucial starting point: our brain.”

This book will give you a glimpse into the chaos of this world: how the brain interacts with the world, how we develop conflicting beliefs, and how we vehemently defend “beliefs that are not worth defending,” ultimately reaching the point of taking someone’s life.

The author emphasizes:

Anyone can be an extreme ideologue, and understanding, tolerance, and compassion begin with recognizing that those with flawed beliefs are imperfect human beings, rather than stereotyping them.

That may be the attitude that humanity needs to take to solve the problem together in the face of a global crisis.

This is precisely why this book is not simply an ethical cry, but an intellectual journey born of cognitive empathy.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

introduction

Acknowledgements

Recommendation

Chapter 1.

Delusions, distortions and

What a wrong belief… … Oh my God!

1 Delusion

2 Cognitive distortions

3 Distrust

ㆍExamining the Evidence | The Paradox of Faith

Chapter 2.

The Psychology of Overconfidence

1 Belief as a probabilistic judgment

2 Healthy Lies We Tell Ourselves

I am better than the average person | I am the master of my own destiny | The future will be especially good for me

3 False memories

4 Dunning-Kruger effect

Chapter 3.

Enhanced confirmation bias

1 Peripheral brain

2 Confirmation bias, confirmation bias, confirmation bias!

3. The Encounter of Delusional Thinking and the Internet

4. Enhanced confirmation bias

5 Fierce online war

Chapter 4.

Opinion Flea Market

1 Misinformation that leads to death

2 Opinion Flea Market

3. The collapse of truth, misinformation, and fake news.

4. Synchronized Inference and Identity Defense

5 Cognitive Laziness vs.

Synchronized accuracy

Chapter 5.

disinformation industry

1. Distributed legal responsibility

2. Distrust and misinformation

3 Top Predators in the Misinformation Food Chain

Information Wars | Distrust of Authority | Spreaders of Disinformation | The Secrets of the Disinformation Business

4 Political Propaganda and the Illusion of Truth Effect

? False fire hose strategy

5 Alternative Facts in a Post-Truth World

Chapter 6.

Out-of-control conspiracy theories

1 Flat Earth Believers

2 The Dark Ages of Conspiracy Theories

3 The Psychology of Conspiracy Beliefs

4. The return of distrust and misinformation

Trust No One | Populist Thinking | Disinformation and the Flow of Money

5 If one goes, all go

Chapter 7.

Fall for the bullshit

1 An example of nonsense

2 Bullshit, Bullshitters, and the Fooled

3 Scientific Nonsense and Pseudoscience

4 Postmodern Nonsense on College Campuses

5 Evasive Nonsense and Politics

6. Spotting Nonsense

Chapter 8.

divided nations

1. Uncompromising Beliefs

2 Identity politics

3 Emotional polarization

ㆍThe dangers of factionalism

4 Racial Politics

Implicit Bias | Identity Threat

5 Left, Right, and Center

6 A more perfect combination

Chapter 9.

Our faith is not us

1 Those who seek the truth

2 Skepticism, Denialism, and Climate Change

ㆍNaive Realism and the Law of the Minority | Climate Science vs.

Big Oil

3 The Immutability of Faith and Sacred Values · Values, Morality, and Identity | Moral Relativism vs.

moral absolutism

4. Five Steps to Ideological Confidence

Non-believers | Neutral believers | True believers | Activists | Apostates

Chapter 10.

A Prescription for the Post-Truth Era

1 From Diagnosis to Treatment

2 Three Key Principles for Obscuring the Truth

Intellectual Humility | Cognitive Flexibility | Analytical Thinking

3 Truth, Justice, and a Better Tomorrow

Education Reform | Content Moderation, Public Criticism, and Censorship | The Voice of the People is the Voice of God

4 Is mutual respect and cooperation possible?

5 If no one cares

References

Acknowledgements

Recommendation

Chapter 1.

Delusions, distortions and

What a wrong belief… … Oh my God!

1 Delusion

2 Cognitive distortions

3 Distrust

ㆍExamining the Evidence | The Paradox of Faith

Chapter 2.

The Psychology of Overconfidence

1 Belief as a probabilistic judgment

2 Healthy Lies We Tell Ourselves

I am better than the average person | I am the master of my own destiny | The future will be especially good for me

3 False memories

4 Dunning-Kruger effect

Chapter 3.

Enhanced confirmation bias

1 Peripheral brain

2 Confirmation bias, confirmation bias, confirmation bias!

3. The Encounter of Delusional Thinking and the Internet

4. Enhanced confirmation bias

5 Fierce online war

Chapter 4.

Opinion Flea Market

1 Misinformation that leads to death

2 Opinion Flea Market

3. The collapse of truth, misinformation, and fake news.

4. Synchronized Inference and Identity Defense

5 Cognitive Laziness vs.

Synchronized accuracy

Chapter 5.

disinformation industry

1. Distributed legal responsibility

2. Distrust and misinformation

3 Top Predators in the Misinformation Food Chain

Information Wars | Distrust of Authority | Spreaders of Disinformation | The Secrets of the Disinformation Business

4 Political Propaganda and the Illusion of Truth Effect

? False fire hose strategy

5 Alternative Facts in a Post-Truth World

Chapter 6.

Out-of-control conspiracy theories

1 Flat Earth Believers

2 The Dark Ages of Conspiracy Theories

3 The Psychology of Conspiracy Beliefs

4. The return of distrust and misinformation

Trust No One | Populist Thinking | Disinformation and the Flow of Money

5 If one goes, all go

Chapter 7.

Fall for the bullshit

1 An example of nonsense

2 Bullshit, Bullshitters, and the Fooled

3 Scientific Nonsense and Pseudoscience

4 Postmodern Nonsense on College Campuses

5 Evasive Nonsense and Politics

6. Spotting Nonsense

Chapter 8.

divided nations

1. Uncompromising Beliefs

2 Identity politics

3 Emotional polarization

ㆍThe dangers of factionalism

4 Racial Politics

Implicit Bias | Identity Threat

5 Left, Right, and Center

6 A more perfect combination

Chapter 9.

Our faith is not us

1 Those who seek the truth

2 Skepticism, Denialism, and Climate Change

ㆍNaive Realism and the Law of the Minority | Climate Science vs.

Big Oil

3 The Immutability of Faith and Sacred Values · Values, Morality, and Identity | Moral Relativism vs.

moral absolutism

4. Five Steps to Ideological Confidence

Non-believers | Neutral believers | True believers | Activists | Apostates

Chapter 10.

A Prescription for the Post-Truth Era

1 From Diagnosis to Treatment

2 Three Key Principles for Obscuring the Truth

Intellectual Humility | Cognitive Flexibility | Analytical Thinking

3 Truth, Justice, and a Better Tomorrow

Education Reform | Content Moderation, Public Criticism, and Censorship | The Voice of the People is the Voice of God

4 Is mutual respect and cooperation possible?

5 If no one cares

References

Detailed image

Into the book

Whether or not individuals know the critical probabilities, they tend to prioritize strength of evidence over weight of evidence and selective personal observations over base rates.

This explanation will no longer sound unfamiliar.

This is because it is in line with the phenomenon that appears from a style of reasoning that leads to hasty conclusions, such as ‘delusional thinking’ and ‘naive realism’ mentioned in Chapter 1, and from an excessive reliance on narrow subjective experiences.

But don't forget that in the end, it's just a difference in degree.

While people with delusions and delusional tendencies may be more susceptible to this type of error, it is also a universal vulnerability that we all share to some degree under certain conditions.

Likewise, the gambler's fallacy is known to occur frequently as a type of cognitive error among 'serious gamblers', but it can still occur in less serious gamblers and perhaps even in all of us.

--- p.56

The Dunning-Kruger effect, along with behavioral economics, positive illusions, and the imperfections of memory, provides a powerful reminder that much of our confidence in what we believe may be unfounded.

Overconfidence may make us look better in the moment, but it is better to acknowledge that we are prone to self-deception in our ignorance and build our self-esteem based on that awareness.

In fact, the moment we look in the mirror and realize what we don't know, whether we're experts or not, can motivate us to learn and grow.

But acquiring such humility is not as easy as it sounds.

So how can we get closer to Socrates' concept of expertise? Recall Kahneman's comments on overconfidence.

He said he wished he had a magic wand that could correct his overconfidence.

Dunning came up with a better answer.

How do I get people to say, "I don't know"? I don't know.

--- p.76

Confirmation bias is closer to intuitive, emotional, "fast thinking" that favors truthiness, or "what we want to believe," over "truth."

As a result, our attention is drawn to information that supports our existing beliefs and we ignore information that contradicts them.

But motivated reasoning goes a step further, a more rational and deliberate process through which we control how we digest and interpret information, trying to justify what we already believe and act in a way that aligns with the beliefs expected of our ideological group.

Therefore, synchronized reasoning can be viewed as a social and cultural cognitive concept that depends not only on the interaction between information and our brain, but also on the triangular relationship between information, our brain, and the ideological group to which we belong.

--- p.146

Today's chaotic flea market of opinions is overflowing with conflicting and misinformation, making it easy to find "evidence" to support any belief.

So, we avoid the conflict between belief and fact by shamelessly selecting misinformation through confirmation bias and motivated reasoning, and instead ridicule the opposing camp as believers of misinformation.

By doing so, we can maintain what Jiva Kunda calls the so-called 'illusion of objectivity'.

In short, we do not use facts to build our beliefs, but rather we use information, whether true or false, to justify the beliefs we and our social groups already hold.

As a result, even fact-checking sites, guides that objectively evaluate media outlets based on credibility and political bias, and lists of predatory journals can be dismissed as "biased," just as the opinions of scientific experts and the consensus of the scientific community can be dismissed out of hand.

--- p.149

If there's one common thread running through the stories I've heard from QAnon supporters—especially the literally fervent QAnon believers who know the ins and outs of QAnon doctrine—it's that they spent an increasing amount of time online in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election.

Laid off or confined to their homes during the pandemic, they became increasingly immersed in the online world of QAnon, increasingly alienating themselves from their old lives and relationships.

Jensen's attorney explained his client's downfall this way:

"Maybe it was a midlife crisis, maybe it was the COVID-19 pandemic, or maybe it was the fact that the QAnon message felt like it was elevating his ordinary life to a sublime one with noble purpose.

In any case, he was caught up in the deluge of information pouring out on the Internet and came to the Capitol at the direction of the US President to prove that he was a 'true patriot.'"

--- p.251~252

We should not dismiss the current conspiracy theory dark age as the result of an older, more extreme form of "paranoid extremism."

We are all susceptible to conspiracy theories.

If anything has changed in recent years, it is that a confluence of social and structural factors has created a crisis of epic proportions that exacerbates the psychological vulnerability that makes us susceptible to conspiracy theories.

A global crisis in which the psychological need for control, certainty, and singularity has become hypertrophied.

A lack of trust in authoritative sources of information has made people susceptible to widespread misinformation and deliberate disinformation.

Also, like-minded people with anti-establishment worldviews struggle to find salvation from enforced social isolation.

And we are blindly drawn to the binary opposition of good and evil, unaware that political leaders are using conspiracy theories to incite angry mobs.

A mentally healthy society does not make important decisions based on false beliefs and conspiracy theories.

Such a society would not allow its democracy to crumble or its people to die because of conspiracy theories.

And yet we are here.

--- p.252~253

Progressives and conservatives seem to focus on different wavelengths of immorality.

To conservatives, progressives seem to have an "anything goes" moral system, believing that even the most bizarre and depraved behavior should be tolerated in the interest of inclusion and diversity.

On the other hand, in the eyes of progressives, conservatives appear to lack even basic moral compassion, especially for oppressed groups, and to take a perverse pleasure in seeing the rich get richer while the innocent suffer in poverty.

In Haight's case, viewing political differences through this lens led him to lose what he called "his moral passion" as a progressive and Democratic supporter.

So now, he says, he's taking a "neutral" stance, viewing both the right's racism and the left's "victim mentality and victim-centered thinking" as further deepening the divisions in American politics.

This explanation will no longer sound unfamiliar.

This is because it is in line with the phenomenon that appears from a style of reasoning that leads to hasty conclusions, such as ‘delusional thinking’ and ‘naive realism’ mentioned in Chapter 1, and from an excessive reliance on narrow subjective experiences.

But don't forget that in the end, it's just a difference in degree.

While people with delusions and delusional tendencies may be more susceptible to this type of error, it is also a universal vulnerability that we all share to some degree under certain conditions.

Likewise, the gambler's fallacy is known to occur frequently as a type of cognitive error among 'serious gamblers', but it can still occur in less serious gamblers and perhaps even in all of us.

--- p.56

The Dunning-Kruger effect, along with behavioral economics, positive illusions, and the imperfections of memory, provides a powerful reminder that much of our confidence in what we believe may be unfounded.

Overconfidence may make us look better in the moment, but it is better to acknowledge that we are prone to self-deception in our ignorance and build our self-esteem based on that awareness.

In fact, the moment we look in the mirror and realize what we don't know, whether we're experts or not, can motivate us to learn and grow.

But acquiring such humility is not as easy as it sounds.

So how can we get closer to Socrates' concept of expertise? Recall Kahneman's comments on overconfidence.

He said he wished he had a magic wand that could correct his overconfidence.

Dunning came up with a better answer.

How do I get people to say, "I don't know"? I don't know.

--- p.76

Confirmation bias is closer to intuitive, emotional, "fast thinking" that favors truthiness, or "what we want to believe," over "truth."

As a result, our attention is drawn to information that supports our existing beliefs and we ignore information that contradicts them.

But motivated reasoning goes a step further, a more rational and deliberate process through which we control how we digest and interpret information, trying to justify what we already believe and act in a way that aligns with the beliefs expected of our ideological group.

Therefore, synchronized reasoning can be viewed as a social and cultural cognitive concept that depends not only on the interaction between information and our brain, but also on the triangular relationship between information, our brain, and the ideological group to which we belong.

--- p.146

Today's chaotic flea market of opinions is overflowing with conflicting and misinformation, making it easy to find "evidence" to support any belief.

So, we avoid the conflict between belief and fact by shamelessly selecting misinformation through confirmation bias and motivated reasoning, and instead ridicule the opposing camp as believers of misinformation.

By doing so, we can maintain what Jiva Kunda calls the so-called 'illusion of objectivity'.

In short, we do not use facts to build our beliefs, but rather we use information, whether true or false, to justify the beliefs we and our social groups already hold.

As a result, even fact-checking sites, guides that objectively evaluate media outlets based on credibility and political bias, and lists of predatory journals can be dismissed as "biased," just as the opinions of scientific experts and the consensus of the scientific community can be dismissed out of hand.

--- p.149

If there's one common thread running through the stories I've heard from QAnon supporters—especially the literally fervent QAnon believers who know the ins and outs of QAnon doctrine—it's that they spent an increasing amount of time online in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election.

Laid off or confined to their homes during the pandemic, they became increasingly immersed in the online world of QAnon, increasingly alienating themselves from their old lives and relationships.

Jensen's attorney explained his client's downfall this way:

"Maybe it was a midlife crisis, maybe it was the COVID-19 pandemic, or maybe it was the fact that the QAnon message felt like it was elevating his ordinary life to a sublime one with noble purpose.

In any case, he was caught up in the deluge of information pouring out on the Internet and came to the Capitol at the direction of the US President to prove that he was a 'true patriot.'"

--- p.251~252

We should not dismiss the current conspiracy theory dark age as the result of an older, more extreme form of "paranoid extremism."

We are all susceptible to conspiracy theories.

If anything has changed in recent years, it is that a confluence of social and structural factors has created a crisis of epic proportions that exacerbates the psychological vulnerability that makes us susceptible to conspiracy theories.

A global crisis in which the psychological need for control, certainty, and singularity has become hypertrophied.

A lack of trust in authoritative sources of information has made people susceptible to widespread misinformation and deliberate disinformation.

Also, like-minded people with anti-establishment worldviews struggle to find salvation from enforced social isolation.

And we are blindly drawn to the binary opposition of good and evil, unaware that political leaders are using conspiracy theories to incite angry mobs.

A mentally healthy society does not make important decisions based on false beliefs and conspiracy theories.

Such a society would not allow its democracy to crumble or its people to die because of conspiracy theories.

And yet we are here.

--- p.252~253

Progressives and conservatives seem to focus on different wavelengths of immorality.

To conservatives, progressives seem to have an "anything goes" moral system, believing that even the most bizarre and depraved behavior should be tolerated in the interest of inclusion and diversity.

On the other hand, in the eyes of progressives, conservatives appear to lack even basic moral compassion, especially for oppressed groups, and to take a perverse pleasure in seeing the rich get richer while the innocent suffer in poverty.

In Haight's case, viewing political differences through this lens led him to lose what he called "his moral passion" as a progressive and Democratic supporter.

So now, he says, he's taking a "neutral" stance, viewing both the right's racism and the left's "victim mentality and victim-centered thinking" as further deepening the divisions in American politics.

--- p.380

Publisher's Review

"The world we see is not 'truth,' but a world shaped by our 'beliefs.'"

The Trap of Confidence Created by 'Quick Thinking'

The formation of false beliefs is not simply a matter of 'ignorance', but rather the result of cognitive biases that arise from the structural characteristics of human thinking.

In the process of perceiving and judging the world, numerous empirical judgment rules (heuristics) are at work.

This kind of 'fast thinking' helps us make quick decisions in a complex world, but it also creates cognitive traps that distort reality.

These are all 'intellectual shortcuts' that we use in our attempts to interpret the world efficiently.

Fast thinking is automatic, intuitive, and based on emotional judgments, while slow thinking is responsible for careful, logical thinking.

Ideally, the two systems should be balanced, but in practice, fast thinking often overpowers slow thinking.

This is where judgment errors occur.

We jump to conclusions based on immediate impressions without sufficiently reviewing the information, which leads to false beliefs.

Even though we know that successive events are independent, like the 'gambler's fallacy', we mistakenly think, "This time will be different."

This is because humans prefer patterns over probabilities.

Cognitive biases are not limited to any particular group; they are a universal vulnerability we all share.

In particular, overconfidence is a particularly powerful bias.

People often mistakenly believe that their knowledge is much broader than it actually is, and they have unfounded confidence in areas they do not know.

Ultimately, the core of false beliefs is a cognitive chain reaction created by the interplay of naive realism, overconfidence, confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, distrust, and exposure to misinformation.

We choose the truth we want to believe over the truth, and we exclude inconvenient evidence in the belief that we are right.

False beliefs are not simply a defect of a particular individual, but a result of structural limitations of the entire human thought system.

How Google Engineers Our Beliefs

The Encounter of Mass Delusion and the Internet: The Birth of a New "Digital Collective"

We can now instantly retrieve any information we need through our 'peripheral brain', the Internet, at any time.

As a result, knowledge feels like it's at our fingertips rather than in our heads, and we develop an unfounded confidence and certainty in the illusion of knowing.

This phenomenon is called the 'Google delusion'.

The algorithms of the Internet and social media exploit this human cognitive tendency in a sophisticated way.

In a structure where the number of clicks is directly linked to profit, algorithms constantly recommend only the information we 'want to see', and as a result, we are trapped in a digital prison called a 'filter bubble'.

In an "echo chamber" where we repeatedly hear only the voices of like-minded people, we build an increasingly certain worldview and dismiss the opinions of others who disagree with us as "wrong."

Ultimately, people with similar ideologies come together to amplify each other's beliefs, and the boundaries of traditional families and local communities are replaced by new "digital groups."

When we accept or reject information, it's not just our brains that are at work; the information environment we navigate also works together.

In this way, the truth becomes more and more distant, and we become more and more convinced of our own order.

“Truth does not exist.”

Top predators of disinformation who 'monetize distrust'

At the top of the information ecosystem are predators who amass money and power by spreading the cynicism that “truth does not exist.”

They fuel a political landscape that favors division over cooperation, the self-deception of "I'm right," and the bias that condemns the opposition as ignorant.

As a result, society is torn apart from the consensus it once held, the foundations of democracy are weakened, and dangerous decisions can follow as scientific evidence is pushed aside.

Our judgment of whom to trust and what to doubt depends on our perception of the information provider's credibility and expertise.

However, confirmation bias and motivated reasoning distort this assessment, pushing people to the extremes of “naivety to believe everything” and “paranoid distrust to trust no one.”

In particular, as trust in traditional knowledge institutions such as the media, government, and medicine erodes, the gap is filled by deliberate misinformation, and distrust becomes a vicious cycle that amplifies lies.

Top predators of disinformation discredit authoritative knowledge institutions and "engineer" lies for financial and political gain.

The middle class of 'prosumers' consumes, reprocesses, and distributes the lies, while the masses at the very bottom passively accept and spread false information as 'prey.'

Ultimately, the revenue model is simple.

Fake news uses its ability to spread farther and faster than the real thing to grab attention and discredit experts and institutions.

They sell miracle cures, survival kits, and other products by presenting themselves as "real experts" and make money through clicks and ads.

They are literally 'monetizing distrust', and we live in an age where the value of truth is traded within that food chain.

How Conspiracy Theories Filled the Cracks in Our Lives and Became a Means of Loyalty and Patriotism

Nonsense that has become the language of the camp

The reason grand secrets sound more enticing than ordinary explanations is simple.

Conspiracy theories transform complex realities into simple narratives and create order out of chaos.

But the current conspiracy theory boom isn't just a matter of imagination.

As trust in authority and experts is shaken, people seek more compelling explanations to cope with fear and confusion.

Conspiracy theories have now gone beyond individual beliefs to become a social phenomenon amplified by social media, communities, and algorithms.

Crises that shake the world, such as pandemics, wars, and economic instability, raise questions like, “Why did this happen?”

Humans instinctively crave the three Cs: control, certainty, and closure.

But a world full of chance and complexity doesn't easily satisfy such desires.

At that time, the idea of an 'invisible mastermind' or a 'hidden designer' became a psychological painkiller that helped to manage anxiety.

When we add to this the "desire for uniqueness"—the desire to know the "real truth" that is different from others—conspiracy theories become a world that provides not just explanations but a sense of belonging and identity.

In this process, our cognition falls into several traps.

The author points out that one more element should be added to the previously mentioned human cognitive characteristics.

It is the ‘tendency to be easily fooled by nonsense.’

When plausible language, scientific terms, or unsubstantiated statistics appear, it refers to reacting to the 'plausibility' before the truth of the content.

At this point, nonsense becomes not a matter of information but of trust, and “operates as a social interaction that is tolerated and even encouraged within a particular community.”

Political groups and online communities use this nonsense as a kind of 'identity language'.

It is not simply a consumption of information, but a declaration of “I am part of this group,” which in turn strengthens the bonds of the community.

As a result, nonsense is not simply misinformation, but functions as a symbol of ‘belonging’ and ‘loyalty.’

The media environment of modern politics is ideally suited to this nonsense.

Short sentences, strong images, and outrage-inducing messages drive clicks and viewership, and those clicks translate into influence.

So the political nonsense doesn't go away.

It is the language of elections, the currency of platforms, and the signal that distinguishes camps.

We no longer listen to logic, we listen to the language of the camp.

“The truth may be slow, but it arrives.”

In search of truth, justice, and a better tomorrow

So, what should we do in this age of immense delusion and confusion? This book presents the following three core principles for discerning the truth.

The ability to admit that you may be wrong (intellectual humility), to adjust your beliefs in the face of new evidence (cognitive flexibility), and to listen to evidence rather than intuition (analytical thinking).

These three are the most powerful shields that protect us from lies and nonsense.

While it is necessary to crack down on or block misinformation, it is not enough.

The solution to escaping a post-truth world is not only to pursue truth, but also to restore the form of justice—responsibility for one's own assertions—as a communal value.

This is why those who spread misinformation must bear social and legal responsibility.

At the same time, a culture of autonomy must be established in which information consumers themselves judge the reliability of the information they encounter and choose to "think about it" rather than "like."

Stopping the spread of lies isn't simply about deleting content; it's about cultivating discerning citizens.

Our society today may not have lost reason and rationality, but rather has transitioned to 'faith.'

What we have lost is not only the truth, but also the language of collective thought that seeks truth together.

So what we need now is not anger, but compassion, respect, and a restoration of community thinking.

The will to cooperate, resolve conflicts, and move forward together toward greater good, even amidst differing opinions.

Isn't that the only way to bring truth and justice back to the center of our society?

In the end, the truth is not about 'winning' but about 'surviving together'.

The Trap of Confidence Created by 'Quick Thinking'

The formation of false beliefs is not simply a matter of 'ignorance', but rather the result of cognitive biases that arise from the structural characteristics of human thinking.

In the process of perceiving and judging the world, numerous empirical judgment rules (heuristics) are at work.

This kind of 'fast thinking' helps us make quick decisions in a complex world, but it also creates cognitive traps that distort reality.

These are all 'intellectual shortcuts' that we use in our attempts to interpret the world efficiently.

Fast thinking is automatic, intuitive, and based on emotional judgments, while slow thinking is responsible for careful, logical thinking.

Ideally, the two systems should be balanced, but in practice, fast thinking often overpowers slow thinking.

This is where judgment errors occur.

We jump to conclusions based on immediate impressions without sufficiently reviewing the information, which leads to false beliefs.

Even though we know that successive events are independent, like the 'gambler's fallacy', we mistakenly think, "This time will be different."

This is because humans prefer patterns over probabilities.

Cognitive biases are not limited to any particular group; they are a universal vulnerability we all share.

In particular, overconfidence is a particularly powerful bias.

People often mistakenly believe that their knowledge is much broader than it actually is, and they have unfounded confidence in areas they do not know.

Ultimately, the core of false beliefs is a cognitive chain reaction created by the interplay of naive realism, overconfidence, confirmation bias, motivated reasoning, distrust, and exposure to misinformation.

We choose the truth we want to believe over the truth, and we exclude inconvenient evidence in the belief that we are right.

False beliefs are not simply a defect of a particular individual, but a result of structural limitations of the entire human thought system.

How Google Engineers Our Beliefs

The Encounter of Mass Delusion and the Internet: The Birth of a New "Digital Collective"

We can now instantly retrieve any information we need through our 'peripheral brain', the Internet, at any time.

As a result, knowledge feels like it's at our fingertips rather than in our heads, and we develop an unfounded confidence and certainty in the illusion of knowing.

This phenomenon is called the 'Google delusion'.

The algorithms of the Internet and social media exploit this human cognitive tendency in a sophisticated way.

In a structure where the number of clicks is directly linked to profit, algorithms constantly recommend only the information we 'want to see', and as a result, we are trapped in a digital prison called a 'filter bubble'.

In an "echo chamber" where we repeatedly hear only the voices of like-minded people, we build an increasingly certain worldview and dismiss the opinions of others who disagree with us as "wrong."

Ultimately, people with similar ideologies come together to amplify each other's beliefs, and the boundaries of traditional families and local communities are replaced by new "digital groups."

When we accept or reject information, it's not just our brains that are at work; the information environment we navigate also works together.

In this way, the truth becomes more and more distant, and we become more and more convinced of our own order.

“Truth does not exist.”

Top predators of disinformation who 'monetize distrust'

At the top of the information ecosystem are predators who amass money and power by spreading the cynicism that “truth does not exist.”

They fuel a political landscape that favors division over cooperation, the self-deception of "I'm right," and the bias that condemns the opposition as ignorant.

As a result, society is torn apart from the consensus it once held, the foundations of democracy are weakened, and dangerous decisions can follow as scientific evidence is pushed aside.

Our judgment of whom to trust and what to doubt depends on our perception of the information provider's credibility and expertise.

However, confirmation bias and motivated reasoning distort this assessment, pushing people to the extremes of “naivety to believe everything” and “paranoid distrust to trust no one.”

In particular, as trust in traditional knowledge institutions such as the media, government, and medicine erodes, the gap is filled by deliberate misinformation, and distrust becomes a vicious cycle that amplifies lies.

Top predators of disinformation discredit authoritative knowledge institutions and "engineer" lies for financial and political gain.

The middle class of 'prosumers' consumes, reprocesses, and distributes the lies, while the masses at the very bottom passively accept and spread false information as 'prey.'

Ultimately, the revenue model is simple.

Fake news uses its ability to spread farther and faster than the real thing to grab attention and discredit experts and institutions.

They sell miracle cures, survival kits, and other products by presenting themselves as "real experts" and make money through clicks and ads.

They are literally 'monetizing distrust', and we live in an age where the value of truth is traded within that food chain.

How Conspiracy Theories Filled the Cracks in Our Lives and Became a Means of Loyalty and Patriotism

Nonsense that has become the language of the camp

The reason grand secrets sound more enticing than ordinary explanations is simple.

Conspiracy theories transform complex realities into simple narratives and create order out of chaos.

But the current conspiracy theory boom isn't just a matter of imagination.

As trust in authority and experts is shaken, people seek more compelling explanations to cope with fear and confusion.

Conspiracy theories have now gone beyond individual beliefs to become a social phenomenon amplified by social media, communities, and algorithms.

Crises that shake the world, such as pandemics, wars, and economic instability, raise questions like, “Why did this happen?”

Humans instinctively crave the three Cs: control, certainty, and closure.

But a world full of chance and complexity doesn't easily satisfy such desires.

At that time, the idea of an 'invisible mastermind' or a 'hidden designer' became a psychological painkiller that helped to manage anxiety.

When we add to this the "desire for uniqueness"—the desire to know the "real truth" that is different from others—conspiracy theories become a world that provides not just explanations but a sense of belonging and identity.

In this process, our cognition falls into several traps.

The author points out that one more element should be added to the previously mentioned human cognitive characteristics.

It is the ‘tendency to be easily fooled by nonsense.’

When plausible language, scientific terms, or unsubstantiated statistics appear, it refers to reacting to the 'plausibility' before the truth of the content.

At this point, nonsense becomes not a matter of information but of trust, and “operates as a social interaction that is tolerated and even encouraged within a particular community.”

Political groups and online communities use this nonsense as a kind of 'identity language'.

It is not simply a consumption of information, but a declaration of “I am part of this group,” which in turn strengthens the bonds of the community.

As a result, nonsense is not simply misinformation, but functions as a symbol of ‘belonging’ and ‘loyalty.’

The media environment of modern politics is ideally suited to this nonsense.

Short sentences, strong images, and outrage-inducing messages drive clicks and viewership, and those clicks translate into influence.

So the political nonsense doesn't go away.

It is the language of elections, the currency of platforms, and the signal that distinguishes camps.

We no longer listen to logic, we listen to the language of the camp.

“The truth may be slow, but it arrives.”

In search of truth, justice, and a better tomorrow

So, what should we do in this age of immense delusion and confusion? This book presents the following three core principles for discerning the truth.

The ability to admit that you may be wrong (intellectual humility), to adjust your beliefs in the face of new evidence (cognitive flexibility), and to listen to evidence rather than intuition (analytical thinking).

These three are the most powerful shields that protect us from lies and nonsense.

While it is necessary to crack down on or block misinformation, it is not enough.

The solution to escaping a post-truth world is not only to pursue truth, but also to restore the form of justice—responsibility for one's own assertions—as a communal value.

This is why those who spread misinformation must bear social and legal responsibility.

At the same time, a culture of autonomy must be established in which information consumers themselves judge the reliability of the information they encounter and choose to "think about it" rather than "like."

Stopping the spread of lies isn't simply about deleting content; it's about cultivating discerning citizens.

Our society today may not have lost reason and rationality, but rather has transitioned to 'faith.'

What we have lost is not only the truth, but also the language of collective thought that seeks truth together.

So what we need now is not anger, but compassion, respect, and a restoration of community thinking.

The will to cooperate, resolve conflicts, and move forward together toward greater good, even amidst differing opinions.

Isn't that the only way to bring truth and justice back to the center of our society?

In the end, the truth is not about 'winning' but about 'surviving together'.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 26, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 460 pages | 682g | 152*225*28mm

- ISBN13: 9791173575884

- ISBN10: 117357588X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)