discourse

|

Description

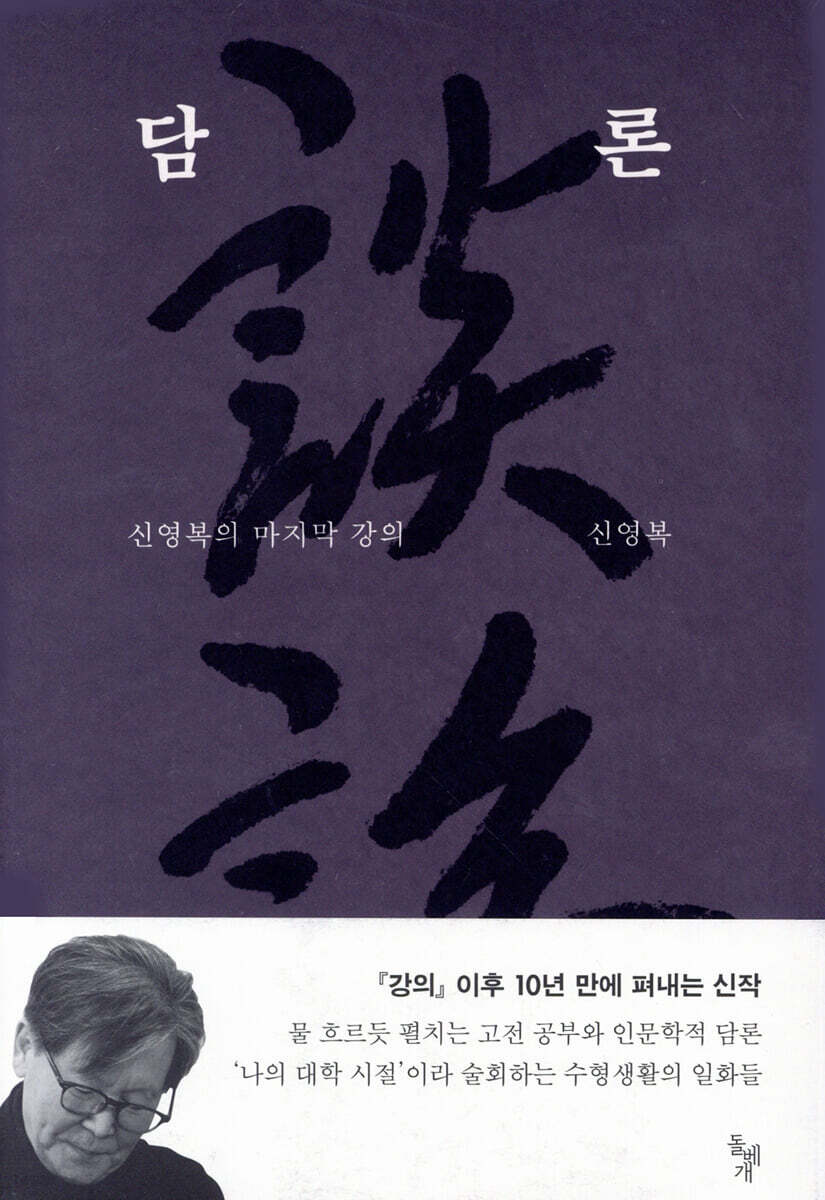

Book Introduction

Discourse: Everything about the lectures of Shin Young-bok, a teacher of our time. 『Discourse: Shin Young-bok's Last Lecture』 is the teacher's 'lecture notes' published 10 years after the publication of 『Lecture』. This book uses not only Eastern classics but also writings from other books by the teacher, such as “Tree, Tree” and “Thoughts from Prison,” as teaching materials, and deals with postmodern discourse, world perception, and human reflection, which he usually discusses, moving from ontology to relationalism. The author will no longer be teaching at a university after the winter semester of 2014. This is why the subtitle of this book is 'The Last Lecture'. The teacher's classroom is always filled with warm and bright energy. The same applies even if the subject matter is classical Chinese literature. How can that be? Because we're pulling the context back to the present and reading it from our perspective. It is the power of ‘empathy.’ “I hope our classroom will be an awakening to the world and humanity, a journey from existence to relationships. I hope that this will be a search for a non-modern organization and a post-modern one. “I hope this will become a space for change and creation.” The lecture room of Professor Shin Young-bok, a place of empathy and communication, has been completely transferred into a book. I hope that this will be a place of comfort and encouragement in the midst of a difficult life. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

discourse

When publishing a book

Part 1: Understanding the World through Classics

1 The Longest Journey

2 Facts and Truth

3 The Wandering Artist

4. A well-used bowl

5 From Tolerance to Nomadism

The six gentlemen are originally poor.

7 points cannot be a line

8 The River That Never Sleeps

9 Suits and Sewing Machines

10 Treat your neighbor as yourself

11 Waiting for yesterday's rabbit

Intermediate Summary? Organization of Contrast and Relationships

Part 2: Understanding Humanity and Self-Reflection

12 Green Barley Field

13 days and 13 days

14 Tragic Beauty

15 Hypocrisy and Hypocrisy

16 Relationships and Perception

17 Rain and Umbrella

18 Objects of Hate

19 Letters and People

20 Huelva and Varanasi

21 Goods and Capital

22.

Dismantling the Pyramid

23 The trembling chronometer

24 human faces

25 The Language of Hope, Seokgwabulsik

When publishing a book

Part 1: Understanding the World through Classics

1 The Longest Journey

2 Facts and Truth

3 The Wandering Artist

4. A well-used bowl

5 From Tolerance to Nomadism

The six gentlemen are originally poor.

7 points cannot be a line

8 The River That Never Sleeps

9 Suits and Sewing Machines

10 Treat your neighbor as yourself

11 Waiting for yesterday's rabbit

Intermediate Summary? Organization of Contrast and Relationships

Part 2: Understanding Humanity and Self-Reflection

12 Green Barley Field

13 days and 13 days

14 Tragic Beauty

15 Hypocrisy and Hypocrisy

16 Relationships and Perception

17 Rain and Umbrella

18 Objects of Hate

19 Letters and People

20 Huelva and Varanasi

21 Goods and Capital

22.

Dismantling the Pyramid

23 The trembling chronometer

24 human faces

25 The Language of Hope, Seokgwabulsik

Publisher's Review

discourse

Shin Young-bok's Lecture Room: A Place of Comfort, Encouragement, Empathy, and Communication

Every Thursday evening at 8 o'clock, people gather in groups of three or five in the lecture room without fail.

This is a lecture room at Sungkonghoe University.

A small university lecture hall in a remote area, not in the heart of Seoul but adjacent to Bucheon City, is teeming with students.

Among the students, there are students from Sungkonghoe University, but there are also quite a few older auditors.

Teachers who teach children at school, office workers at insurance companies, banks, and other general companies.

This is Professor Shin Young-bok's lecture room, where people from various professions have gathered.

The teacher says that he has learned something through his long teaching experience.

First, the relationship between teachers and students is not asymmetrical, and second, there should be no attempt to persuade or indoctrinate.

A person's thoughts are the conclusion of their life and are very stubborn, so you shouldn't think you can persuade or indoctrinate them.

So, the teacher's lectures are centered around problems that have no correct answers.

The teacher's classroom is always filled with laughter.

The wit and humor of an old scholar in his seventies is something that young people simply cannot match.

There is a textbook, but they don't ask you to read it in advance.

The reason is, first of all, that even if you ask people to read it in advance, there are not many people who will read it.

Second, the classroom scene where one person reads aloud a textbook and everyone listens quietly together is the pinnacle of empathy.

The classroom is filled with the energy of communication as one student reads from the textbook.

“Ah! You were thinking that too!”, this heartwarming comfort is conveyed.

The teacher's lecture is like a journey that many people go on together.

On the last day of the long journey that began in autumn and continued through late autumn and until the snows of early winter, the teacher took all the students to the bottom of a bare zelkova tree.

And he asks each of them to hang a beautiful star on the end of a branch.

Although we cannot be together forever, isn't it meant to ask each and every student to have a star in their heart that will shine like the North Star on their long journey ahead?

After being released from prison on special parole in 1988, the professor began teaching at Sungkonghoe University the following year in 1989, and continued to lecture as a distinguished professor even after his retirement in 2006.

I have been teaching at universities for almost 25 years.

The professor will no longer be teaching at the university after the winter semester of 2014.

Except for the occasional special lectures for the general public, it seems unlikely that you will see the professor on a university podium.

Instead, the teacher reveals that he is making up for his regret of not being able to stand on the podium with this book.

This book is based on a manuscript recorded from the author's lectures at Sungkonghoe University.

The teacher's lecture was recorded a total of three times.

It was conducted without the teacher's prior consent, and the students recorded it voluntarily according to their own needs.

After receiving the transcript, the teacher confessed that he felt ashamed because his lectures were repetitive and lacked content. However, the 'lecture materials' that the teacher personally edited and created and the several volumes of 'lecture notes' that he organized for his lectures show that not a single lecture was wasted.

The 'discourse' that unfolds calmly like flowing water contains the teacher's high level of restraint and strong spirit.

『Discourse』 is based on the teacher's "Lecture Notes 2014-2" and transcripts.

A Flexible Framework for World Perception in Eastern Classics

[Lecture] 10 Years Later, My Reading of Eastern Classics Has Deepened and Richer

Following the publication of 『Lecture』 in 2004, in his new work 『Discourse』, the teacher perceives the world through the thinking of ‘relationalism’ through the reading of Eastern classics.

The reason I chose Eastern classics as my study text is because the rich ideas they contain are the core of my understanding of the world.

The ideas contained in Eastern classics are, above all, centered on humans.

Here, human-centeredness does not mean humanism that assumes humans as exclusive beings or places humans at the center of the universe.

In Eastern thought, humans are one of the three elements of heaven, earth, and man, and are both a part and a whole.

The harmony and balance inherent in Eastern thought, as well as its excellent perspective for reflecting on the past and envisioning the future, provide a flexible framework for correctly perceiving the world.

The teacher reads the classics in their current context and connects them to today's challenges.

Of course, this method of interpretation would not be acceptable to positivists, but the teacher thinks differently.

Every classic must be a dynamic space where past and present intersect, where reality and imagination, reality and ideals intersect.

The Confucian view of development and the belief in progress must also be reexamined from the perspective of whether the capital accumulation method of modern financial capital is truly sustainable.

In this way, the Eastern classics discussed in this book are not obsessed with literal interpretations or the meaning of individual words, but are read anew in the current context by combining them with various aspects of our current society.

The teacher believes that every text should be read anew.

Additionally, by sharing various anecdotes from the teacher's experiences and the small, everyday things he experienced in his life, he makes it easier to understand the modern context of Eastern classics.

This book is the definitive guide to reading Eastern classics, containing much deeper discussions and richer examples over the past ten years since 『Lectures』.

The Book of Songs: Containing the World Through the Poet's Sensibility, Not Through the Small Vessel of a Literary "Concept"

Poetry contains truth that transcends facts.

Poetry is not part of the rational realm of literature, history, and philosophy, but belongs to the emotional realm along with calligraphy, painting, and music.

It is free from concepts and logical thinking.

It broadens our horizon of perception.

What we must pay attention to in poetry is the poetic perspective as a flexible ‘frame of perception.’

The teacher talks about the importance of a framework of perception by 'contrasting' the realism and authenticity of the 『Book of Songs』 and the romance and creativity of the 『Chushi』.

We are trapped in a rigid framework of perception called the literary world.

Munsacheol is a literary narrative form centered on language, concepts, and logic.

It goes without saying that we cannot contain the constantly changing world with the abstract vessels of language, concepts, and logic, nor can we perceive the world properly.

It's like not being able to put the vast ocean into the word 'sea'.

Breaking these perceptions is the beginning of learning.

The poetic perspective is not the best alternative, but it is an excellent perspective from which to reflect on the rigid framework of literary narrative form.

And, it is most important to develop both ‘abstraction’ through literary studies and ‘imagination’ through poetry, calligraphy, painting, and music.

Studying rationality and emotionality must be done simultaneously.

Through the story of an elderly inmate he met in prison, the teacher talks about how to understand people and how truth is a more honest perception of the world than facts.

On the first day a newcomer arrives, this old man invariably calls the newcomer over and sits him down, telling him the story of his long life.

This life story is of course not true.

By leaving out the embarrassing things and exaggerating the heroic or good stories, a few years later, he becomes the main character of a pretty cool drama.

It is said that the teacher had this thought one day in late autumn when it was drizzling and he was looking at the back of an old man who was staring out the iron bars.

'If that old man were to start his life over again, wouldn't he at least try to live the life he'd portrayed in the story?' If so, to properly understand this old man, shouldn't we see him not as a seemingly inmate, but as a true protagonist with hope and reflection?

The reason for borrowing the framework of poetry, calligraphy, painting, and music rather than the rigid framework of Munsa Cheol is that the poetic perspective is faithful to reality and social beauty, but is not confined to the facts themselves.

The Book of Changes: To fully understand the world, one must examine the relationships between people.

In the 『Book of Changes』, the topic of this lecture is ‘relationship theory’.

We perceive people as individuals, even as numbers.

But to fully understand a person, we must place him or her within the network of relationships he or she has.

This is the framework of perception of the 『Book of Changes』.

In this regard, Professor Shin Young-bok tells the story of the prison episode of Professor Lee Ung-no, who was imprisoned during the East Berlin Incident.

Mr. Goam, who called prisoners by their names rather than their numbers.

The anecdote of the teacher saying to a prisoner named 'Eung-il', "Whose eldest son is in prison?" shows the difference in the framework of perceiving people.

If the relational theory of the Book of Changes serves as a framework for perception, the person who was perceived as a number becomes 'the eldest son of someone' - this is a big difference.

The Analects: The idea that "unification is a great fortune" is hegemonism and the logic of the same.

The discourse on harmony and unity in the Analects is an abbreviation of the saying, “A gentleman is harmonious but different,” and “A small man is harmonious but different.”

“A gentleman recognizes diversity and does not seek to dominate, while a petty man seeks to dominate and cannot coexist.”

Just as the concept of a gentleman and a small man is a concept of contrast, harmony and sameness should also be read as concepts of contrast.

This discourse on the flower boy is the world view of the Confucian school of the Spring and Autumn Period.

They oppose annexation through war and advocate for a world of harmony where large and small countries, strong and weak countries coexist peacefully.

Harmony (和) is the logic of tolerance and coexistence that respects diversity, while sameness (同) is the logic of domination and merger and absorption.

The reason why the teacher rereads the discourse of Hwadong in a modern context is because the same logic can illuminate today's hegemonic structure.

Hegemonic order is the trend of our time.

The US invasion of Iraq is a violent act by a powerful country to maintain dollar hegemony, and it is the same logic.

We must consider whether the hegemonic structure of a great power, marked by massive destruction and killing, can truly be sustained.

The hegemonic structure is still intact.

The discourse on Hwadong also has very important issues as our country's 'discourse on unification.'

The teacher writes unification as '通一'.

Peaceful settlement, exchange and cooperation, and acceptance of differences and diversity are what constitute 'unification.'

If 'unification' is achieved, the road to 'unification' will also be smooth, although we don't know when that will be.

The idea that “unification is a jackpot” mentioned by President Park Geun-hye some time ago is an extremely economical idea, and its foundation is the logic of the same.

Expressing the nation's long-cherished wish and tearful reconciliation as a 'daebak' is an economic logic that views unification.

If unification suddenly comes like a jackpot, as the president said, it will be a disaster and a shock.

Unification is sufficient as unification.

Mencius: A Dwarfed Encounter in a Capitalist Society Without "Relationships"

There is a famous parable in the Mencius, commonly called the 'Goksokjang'.

This is an anecdote about a king of the state of Qi during the Warring States period who saw an ox being taken as a sacrifice and felt sorry for it, so he ordered that it be replaced with a sheep.

What this story is trying to say is not compassion for animals.

Why did he change the cow into a sheep? Because he saw the cow but not the sheep.

The most important thing is the fact that we ‘see’.

To see means to 'meet', and to see [見], to meet [友], and to know [知] each other.

That is, 'relationship'.

What we must draw from this passage is the reality of our society, which lacks encounters.

As we see in the news, the reason why 'unthinkable things' are happening so brazenly is because there is no 'meeting'.

The reason that harmful substances can be added to food is because the producer has not met the consumer.

Since we have no relationship with each other, there is no need to care about each other.

Although the cause of this indifference and cold human relations is sometimes explained as the characteristics of cities, cities are created by capitalism.

The city is the existential form in which capitalism actually exists.

Along with this parable from Mencius, the teacher introduces an anecdote about the subway that he personally experienced.

It is said that the teacher can almost accurately predict who will get off at which station on the subway, perhaps because of his long prison term.

One day, I was standing right in front of someone who was getting off at Sindorim Station, and as expected, when the train arrived at Sindorim Station, that person stood up.

The moment the teacher was about to sit down, the woman sitting right next to him quickly moved to that seat and helped her friend who was standing in front of him sit in her seat, an entirely unexpected event occurred.

What the teacher was reminded of here was this parable from Mencius.

The woman and the teacher have never met, and never will.

A very brief encounter on the subway does not establish a 'relationship'.

They say that if they had lived together in that subway for about three years, eating, sleeping, and living together, that person would not have done such a thing.

We live in a society where human contact and intergenerational contact are cut off.

The Difference Between an Illegal Offender and a Criminal

In 『Han Feizi』, through the story of Tak (度) and Jok (足) of Cha Chiri who went to the market to buy shoes, it talks about our foolishness of not being able to properly perceive the changing world and being trapped in a rigid framework of perception.

The teacher says that we are like teacups going back home to get a table.

When we try to solve a difficult problem, instead of facing the reality itself, we go to the library or search the Internet to find a model of reality.

It is more trusting in books that model reality than in facing the reality itself.

This rigid framework of perception is similar to the framework we use to evaluate people.

The principle of the Legalists during the Warring States Period was that everyone should be punished with punishment regardless of class, but at the time, the prevailing principle of punishment was to punish those above the rank of magnate with rites and commoners with punishments.

And our current judicial reality is similar to this.

Politicians and economic criminals are given light punishments and their sentences are pardoned after a while.

There is a saying, 'Innocent until proven guilty, guilty until proven guilty.'

And a bigger problem than this judicial reality is our social consciousness.

Political and economic criminals are recognized as 'illegal actors', while common criminals such as theft and robbery are called 'criminals'.

It's a huge difference in perception.

On one hand, only the person's 'actions' are illegal, while on the other hand, 'the human being itself' becomes a criminal.

It is a stubborn frame of mind.

20 years and 20 days, my college days

Words Left Unsaid in the 'Censored' Letter

The teacher's representative work, "Reflections from Prison," is a collection of letters he sent to his family while in prison.

The teacher's letters were addressed to his wife, sister-in-law, and parents, but they contained sincere reflections on humanity and society.

The process leading up to the publication of this book is somewhat known, but the newly published [Discourse] details the circumstances leading up to the book's publication.

The writings in 『Reflections from Prison』 are all neat and calm.

The hardships and suffering of prison life are not visible at all.

Why is that? Many readers of this book ask the same question.

The teacher explained the reason as follows:

First, because the family was the ultimate readers of the letters.

The least a teacher could do for his family was to show them that he was living an upright life.

Second, because the letter was censored.

It was a pride that prevented the state power, represented by the prison authorities, from collapsing through self-censorship before censoring the letter.

In this book, 『Discourse』, I included words that were not written in the censored letters.

He described not only the hardships and suffering of prison life, but also his state of mind at the time he wrote the letter.

You can read the meaning between the lines of the letters included in [Reflections from Prison].

Autobiographical writings of Shin Young-bok

It is a well-known fact that Mr. Shin Young-bok was sentenced to death for his involvement in the Tonghyeokdang incident and later served 20 years and 20 days as a life prisoner.

However, he has rarely mentioned in detail his feelings since he was first sentenced to death and later served a life sentence.

The [discourse] is like Shin Young-bok's autobiography, including his state of mind at the time he wrote "Memories of the Claims Court," and the reason he did not commit suicide during his long life as a life sentence prisoner.

* Memories of "Billing Memories"

"Memories of the Claims Court" is a story written by the teacher while he was on death row for nearly a year at the Namhansanseong Army Prison in 1969. It is a story about children he met in front of Jangchung Gymnasium at 5 PM on the last Saturday of every month.

This is a message written on two sheets of recycled paper given out each day, to remind me of the children who wait in front of Jangchung Gymnasium every Saturday, unaware that their teacher is in prison, and to ensure that I never forget the memories I have with those children.

The teacher said of this writing, “It was more of a recollection than a record, and it was a time of salvation, walking from the gloomy darkness of the jade room to the splendid Seooreung like azalea flowers.”

This article was discovered more than 20 years later, the year after his release.

A young man is said to have delivered it to his home. It seems to be the same military policeman who had been transferred after receiving a transfer notice and had hurriedly left a bundle of toilet paper.

Thanks to that young man, this writing was not forgotten and was included in the expanded edition of 『Reflections from Prison』 in 1998, and was later published as a book with illustrations.

* Why I didn't commit suicide

After spending a year on death row at Namhansanseong Fortress, the teacher was transferred to a civilian prison as a life sentence prisoner.

The teacher describes his 20 years in prison as “my college days,” but at the time, it was a long cave whose end was unimaginable.

An inmate who had been incarcerated for 10 years committed suicide in a prison where the teacher was.

It is said that he died after cutting his wrists in the bathroom in the middle of the night.

The prison has a clause in its [inmate compliance guidelines] that says suicide is not allowed, so this must mean that this kind of thing happens frequently.

The teacher said that he had a harsh near-death experience as a death row inmate at Namhansanseong Fortress, and that he often agonized over the 20 years he served in prison.

“Why am I serving an indefinite life sentence instead of committing suicide?”

The teacher confesses that the reason he did not commit suicide was because of the 'sunshine'.

He says that the warmth of having a newspaper-sized piece of sunlight on your lap, which lasts only two hours at most, was the pinnacle of being alive.

For the teacher, the sunlight in the winter solitary cell was the reason he lived without committing suicide, and it was life itself.

Even through the horrific near-death experience at Namhansanseong Fortress and the seemingly endless tunnel of life imprisonment, the teacher never gave up.

Rather, I learned about history, society, and humanity through it.

Mr. Shin Young-bok, who constantly reformed, changed, escaped, and protected himself like an abstraction.

That is why we call teachers the adults of this age.

20 years and 20 days of college life

It is no exaggeration to say that the teacher's understanding of humanity is the result of his long life in prison.

The teacher recounts how he walked through the lives of countless inmates in a prison where practice was eliminated, and how this gave him the ability to understand humanity and, furthermore, to reflect on himself.

Therefore, the teacher's understanding of humanity is direct and first-person.

The teacher describes his 20 years in prison as 'my college days.'

You say that the term "university years" was inspired by Maxim Gorky's "My University," but the 20 years of imprisonment that you refer to as your university years were as harsh as Gorky's arduous "university of life," and it was a world of steel that ordinary people could not even dare to imagine.

But for the teacher, solitary confinement was a philosophy classroom, and prison was a sociology classroom, a history classroom, and ultimately a anthropology classroom.

This book contains the lives of many inmates the teacher met in prison.

The story of the teacher, which features a diverse group of human figures, includes the story of the trumpeter, who burst into tears wanting to live while looking at the green barley fields, the little boy who became famous as a rice cake believer alongside the teacher, Pastor Cho who secretly ate hardtack in the middle of the night, the elderly long-term prisoners with a surprisingly flexible way of thinking that “left-leaning in theory, right-leaning in practice,” the story of the “tragic protagonist” who believes that everyone born into this world is the protagonist of their own life, and the inmate who was tormented by his conscience for donating blood mixed with water.

If in 『Reflections from Prison』 they appeared flat, in this book 『Discourse』 they come to life in three dimensions, one by one, along with the teacher's honest confession of his feelings.

It must have been difficult for the teacher to relive and relive each and every experience he had with the people he met in prison.

Yet, why does the teacher willingly share his story with us? Perhaps it's because he hopes that we, who live lives of empty theory without practice, can use his story as a crutch to stand on our own two feet and live a life of practice.

* Studying is the effort to take two steps: The story of the old carpenter Moon Do-duk

In prison, the teacher met an old carpenter with the amusing name of Moon Do-deok.

The teacher is shocked to see the carpenter's drawing of a house, which he had drawn carelessly on the ground with a wooden skewer.

A carpenter starts with the cornerstone and draws the roof last, while a teacher who has only developed his ideas through books draws the roof first.

There is a big difference between someone who practices and someone who only has theories.

Through this anecdote, the teacher points out the problem of 'tolerance', which is considered the highest level of modernization.

If you look at this picture and say, “Okay.

You draw from the cornerstone.

I draw from the roof.

If we say, “We respect each other’s differences and coexist,” then this is tolerance.

Of course, it is very important to respect differences and acknowledge diversity.

However, differences and diversity should be another starting point that leads to self-change.

Differences should not be objects of coexistence, but objects of gratitude, should be a textbook for learning, and should be the beginning of change.

If tolerance is the knowledge in your head coming down to your heart, then moving towards self-transformation is a journey of practice from your heart to your feet, an escape, and nomadism.

It is post-modern.

* The shallowness of human understanding: hypocrisy and hypocrisy

Many prison inmates have tattoos.

Tattoos are a declaration that you are a bad person, a bad tempered person.

It is hypocrisy.

It's one way for the weak to survive in this tough world.

On the contrary, hypocrisy is the clothing and disguise of the strong.

It is only what is shown on the surface, not the essence.

The red headbands we often see at protest sites are a type of tattoo.

It is a hypocritical expression of the weak showing off their unity and fighting spirit.

The court is the place for the strong.

The solemnity and quietness of the black robes contrasts sharply with the commotion at the protest site.

The problem is that hypocrisy is judged as a virtue and hypocrisy as a crime.

This is also the logic of the strong.

The logic that terrorism is destruction and murder, and war is peace and justice is the hypocrisy of the powerful.

If terrorism is the war of the weak, then war is the terrorism of the strong.

Nevertheless, our reality boldly uses the contradictory term 'war on terror'.

We must study to remove the veil of hypocrisy and falsehood.

Of course, it is nearly impossible for us to face the reality amidst the illusion created by the splendid stage and costumes, the dazzling lighting of audio and video, and the countless words.

But the greater cause of failure lies not in these devices, but in the shallowness of our human understanding.

We must blame the lack of truly human effort to evenly cultivate love and hate for humans.

Studying is a deepening of our inner self.

Shin Young-bok's Lecture Room: A Place of Comfort, Encouragement, Empathy, and Communication

Every Thursday evening at 8 o'clock, people gather in groups of three or five in the lecture room without fail.

This is a lecture room at Sungkonghoe University.

A small university lecture hall in a remote area, not in the heart of Seoul but adjacent to Bucheon City, is teeming with students.

Among the students, there are students from Sungkonghoe University, but there are also quite a few older auditors.

Teachers who teach children at school, office workers at insurance companies, banks, and other general companies.

This is Professor Shin Young-bok's lecture room, where people from various professions have gathered.

The teacher says that he has learned something through his long teaching experience.

First, the relationship between teachers and students is not asymmetrical, and second, there should be no attempt to persuade or indoctrinate.

A person's thoughts are the conclusion of their life and are very stubborn, so you shouldn't think you can persuade or indoctrinate them.

So, the teacher's lectures are centered around problems that have no correct answers.

The teacher's classroom is always filled with laughter.

The wit and humor of an old scholar in his seventies is something that young people simply cannot match.

There is a textbook, but they don't ask you to read it in advance.

The reason is, first of all, that even if you ask people to read it in advance, there are not many people who will read it.

Second, the classroom scene where one person reads aloud a textbook and everyone listens quietly together is the pinnacle of empathy.

The classroom is filled with the energy of communication as one student reads from the textbook.

“Ah! You were thinking that too!”, this heartwarming comfort is conveyed.

The teacher's lecture is like a journey that many people go on together.

On the last day of the long journey that began in autumn and continued through late autumn and until the snows of early winter, the teacher took all the students to the bottom of a bare zelkova tree.

And he asks each of them to hang a beautiful star on the end of a branch.

Although we cannot be together forever, isn't it meant to ask each and every student to have a star in their heart that will shine like the North Star on their long journey ahead?

After being released from prison on special parole in 1988, the professor began teaching at Sungkonghoe University the following year in 1989, and continued to lecture as a distinguished professor even after his retirement in 2006.

I have been teaching at universities for almost 25 years.

The professor will no longer be teaching at the university after the winter semester of 2014.

Except for the occasional special lectures for the general public, it seems unlikely that you will see the professor on a university podium.

Instead, the teacher reveals that he is making up for his regret of not being able to stand on the podium with this book.

This book is based on a manuscript recorded from the author's lectures at Sungkonghoe University.

The teacher's lecture was recorded a total of three times.

It was conducted without the teacher's prior consent, and the students recorded it voluntarily according to their own needs.

After receiving the transcript, the teacher confessed that he felt ashamed because his lectures were repetitive and lacked content. However, the 'lecture materials' that the teacher personally edited and created and the several volumes of 'lecture notes' that he organized for his lectures show that not a single lecture was wasted.

The 'discourse' that unfolds calmly like flowing water contains the teacher's high level of restraint and strong spirit.

『Discourse』 is based on the teacher's "Lecture Notes 2014-2" and transcripts.

A Flexible Framework for World Perception in Eastern Classics

[Lecture] 10 Years Later, My Reading of Eastern Classics Has Deepened and Richer

Following the publication of 『Lecture』 in 2004, in his new work 『Discourse』, the teacher perceives the world through the thinking of ‘relationalism’ through the reading of Eastern classics.

The reason I chose Eastern classics as my study text is because the rich ideas they contain are the core of my understanding of the world.

The ideas contained in Eastern classics are, above all, centered on humans.

Here, human-centeredness does not mean humanism that assumes humans as exclusive beings or places humans at the center of the universe.

In Eastern thought, humans are one of the three elements of heaven, earth, and man, and are both a part and a whole.

The harmony and balance inherent in Eastern thought, as well as its excellent perspective for reflecting on the past and envisioning the future, provide a flexible framework for correctly perceiving the world.

The teacher reads the classics in their current context and connects them to today's challenges.

Of course, this method of interpretation would not be acceptable to positivists, but the teacher thinks differently.

Every classic must be a dynamic space where past and present intersect, where reality and imagination, reality and ideals intersect.

The Confucian view of development and the belief in progress must also be reexamined from the perspective of whether the capital accumulation method of modern financial capital is truly sustainable.

In this way, the Eastern classics discussed in this book are not obsessed with literal interpretations or the meaning of individual words, but are read anew in the current context by combining them with various aspects of our current society.

The teacher believes that every text should be read anew.

Additionally, by sharing various anecdotes from the teacher's experiences and the small, everyday things he experienced in his life, he makes it easier to understand the modern context of Eastern classics.

This book is the definitive guide to reading Eastern classics, containing much deeper discussions and richer examples over the past ten years since 『Lectures』.

The Book of Songs: Containing the World Through the Poet's Sensibility, Not Through the Small Vessel of a Literary "Concept"

Poetry contains truth that transcends facts.

Poetry is not part of the rational realm of literature, history, and philosophy, but belongs to the emotional realm along with calligraphy, painting, and music.

It is free from concepts and logical thinking.

It broadens our horizon of perception.

What we must pay attention to in poetry is the poetic perspective as a flexible ‘frame of perception.’

The teacher talks about the importance of a framework of perception by 'contrasting' the realism and authenticity of the 『Book of Songs』 and the romance and creativity of the 『Chushi』.

We are trapped in a rigid framework of perception called the literary world.

Munsacheol is a literary narrative form centered on language, concepts, and logic.

It goes without saying that we cannot contain the constantly changing world with the abstract vessels of language, concepts, and logic, nor can we perceive the world properly.

It's like not being able to put the vast ocean into the word 'sea'.

Breaking these perceptions is the beginning of learning.

The poetic perspective is not the best alternative, but it is an excellent perspective from which to reflect on the rigid framework of literary narrative form.

And, it is most important to develop both ‘abstraction’ through literary studies and ‘imagination’ through poetry, calligraphy, painting, and music.

Studying rationality and emotionality must be done simultaneously.

Through the story of an elderly inmate he met in prison, the teacher talks about how to understand people and how truth is a more honest perception of the world than facts.

On the first day a newcomer arrives, this old man invariably calls the newcomer over and sits him down, telling him the story of his long life.

This life story is of course not true.

By leaving out the embarrassing things and exaggerating the heroic or good stories, a few years later, he becomes the main character of a pretty cool drama.

It is said that the teacher had this thought one day in late autumn when it was drizzling and he was looking at the back of an old man who was staring out the iron bars.

'If that old man were to start his life over again, wouldn't he at least try to live the life he'd portrayed in the story?' If so, to properly understand this old man, shouldn't we see him not as a seemingly inmate, but as a true protagonist with hope and reflection?

The reason for borrowing the framework of poetry, calligraphy, painting, and music rather than the rigid framework of Munsa Cheol is that the poetic perspective is faithful to reality and social beauty, but is not confined to the facts themselves.

The Book of Changes: To fully understand the world, one must examine the relationships between people.

In the 『Book of Changes』, the topic of this lecture is ‘relationship theory’.

We perceive people as individuals, even as numbers.

But to fully understand a person, we must place him or her within the network of relationships he or she has.

This is the framework of perception of the 『Book of Changes』.

In this regard, Professor Shin Young-bok tells the story of the prison episode of Professor Lee Ung-no, who was imprisoned during the East Berlin Incident.

Mr. Goam, who called prisoners by their names rather than their numbers.

The anecdote of the teacher saying to a prisoner named 'Eung-il', "Whose eldest son is in prison?" shows the difference in the framework of perceiving people.

If the relational theory of the Book of Changes serves as a framework for perception, the person who was perceived as a number becomes 'the eldest son of someone' - this is a big difference.

The Analects: The idea that "unification is a great fortune" is hegemonism and the logic of the same.

The discourse on harmony and unity in the Analects is an abbreviation of the saying, “A gentleman is harmonious but different,” and “A small man is harmonious but different.”

“A gentleman recognizes diversity and does not seek to dominate, while a petty man seeks to dominate and cannot coexist.”

Just as the concept of a gentleman and a small man is a concept of contrast, harmony and sameness should also be read as concepts of contrast.

This discourse on the flower boy is the world view of the Confucian school of the Spring and Autumn Period.

They oppose annexation through war and advocate for a world of harmony where large and small countries, strong and weak countries coexist peacefully.

Harmony (和) is the logic of tolerance and coexistence that respects diversity, while sameness (同) is the logic of domination and merger and absorption.

The reason why the teacher rereads the discourse of Hwadong in a modern context is because the same logic can illuminate today's hegemonic structure.

Hegemonic order is the trend of our time.

The US invasion of Iraq is a violent act by a powerful country to maintain dollar hegemony, and it is the same logic.

We must consider whether the hegemonic structure of a great power, marked by massive destruction and killing, can truly be sustained.

The hegemonic structure is still intact.

The discourse on Hwadong also has very important issues as our country's 'discourse on unification.'

The teacher writes unification as '通一'.

Peaceful settlement, exchange and cooperation, and acceptance of differences and diversity are what constitute 'unification.'

If 'unification' is achieved, the road to 'unification' will also be smooth, although we don't know when that will be.

The idea that “unification is a jackpot” mentioned by President Park Geun-hye some time ago is an extremely economical idea, and its foundation is the logic of the same.

Expressing the nation's long-cherished wish and tearful reconciliation as a 'daebak' is an economic logic that views unification.

If unification suddenly comes like a jackpot, as the president said, it will be a disaster and a shock.

Unification is sufficient as unification.

Mencius: A Dwarfed Encounter in a Capitalist Society Without "Relationships"

There is a famous parable in the Mencius, commonly called the 'Goksokjang'.

This is an anecdote about a king of the state of Qi during the Warring States period who saw an ox being taken as a sacrifice and felt sorry for it, so he ordered that it be replaced with a sheep.

What this story is trying to say is not compassion for animals.

Why did he change the cow into a sheep? Because he saw the cow but not the sheep.

The most important thing is the fact that we ‘see’.

To see means to 'meet', and to see [見], to meet [友], and to know [知] each other.

That is, 'relationship'.

What we must draw from this passage is the reality of our society, which lacks encounters.

As we see in the news, the reason why 'unthinkable things' are happening so brazenly is because there is no 'meeting'.

The reason that harmful substances can be added to food is because the producer has not met the consumer.

Since we have no relationship with each other, there is no need to care about each other.

Although the cause of this indifference and cold human relations is sometimes explained as the characteristics of cities, cities are created by capitalism.

The city is the existential form in which capitalism actually exists.

Along with this parable from Mencius, the teacher introduces an anecdote about the subway that he personally experienced.

It is said that the teacher can almost accurately predict who will get off at which station on the subway, perhaps because of his long prison term.

One day, I was standing right in front of someone who was getting off at Sindorim Station, and as expected, when the train arrived at Sindorim Station, that person stood up.

The moment the teacher was about to sit down, the woman sitting right next to him quickly moved to that seat and helped her friend who was standing in front of him sit in her seat, an entirely unexpected event occurred.

What the teacher was reminded of here was this parable from Mencius.

The woman and the teacher have never met, and never will.

A very brief encounter on the subway does not establish a 'relationship'.

They say that if they had lived together in that subway for about three years, eating, sleeping, and living together, that person would not have done such a thing.

We live in a society where human contact and intergenerational contact are cut off.

The Difference Between an Illegal Offender and a Criminal

In 『Han Feizi』, through the story of Tak (度) and Jok (足) of Cha Chiri who went to the market to buy shoes, it talks about our foolishness of not being able to properly perceive the changing world and being trapped in a rigid framework of perception.

The teacher says that we are like teacups going back home to get a table.

When we try to solve a difficult problem, instead of facing the reality itself, we go to the library or search the Internet to find a model of reality.

It is more trusting in books that model reality than in facing the reality itself.

This rigid framework of perception is similar to the framework we use to evaluate people.

The principle of the Legalists during the Warring States Period was that everyone should be punished with punishment regardless of class, but at the time, the prevailing principle of punishment was to punish those above the rank of magnate with rites and commoners with punishments.

And our current judicial reality is similar to this.

Politicians and economic criminals are given light punishments and their sentences are pardoned after a while.

There is a saying, 'Innocent until proven guilty, guilty until proven guilty.'

And a bigger problem than this judicial reality is our social consciousness.

Political and economic criminals are recognized as 'illegal actors', while common criminals such as theft and robbery are called 'criminals'.

It's a huge difference in perception.

On one hand, only the person's 'actions' are illegal, while on the other hand, 'the human being itself' becomes a criminal.

It is a stubborn frame of mind.

20 years and 20 days, my college days

Words Left Unsaid in the 'Censored' Letter

The teacher's representative work, "Reflections from Prison," is a collection of letters he sent to his family while in prison.

The teacher's letters were addressed to his wife, sister-in-law, and parents, but they contained sincere reflections on humanity and society.

The process leading up to the publication of this book is somewhat known, but the newly published [Discourse] details the circumstances leading up to the book's publication.

The writings in 『Reflections from Prison』 are all neat and calm.

The hardships and suffering of prison life are not visible at all.

Why is that? Many readers of this book ask the same question.

The teacher explained the reason as follows:

First, because the family was the ultimate readers of the letters.

The least a teacher could do for his family was to show them that he was living an upright life.

Second, because the letter was censored.

It was a pride that prevented the state power, represented by the prison authorities, from collapsing through self-censorship before censoring the letter.

In this book, 『Discourse』, I included words that were not written in the censored letters.

He described not only the hardships and suffering of prison life, but also his state of mind at the time he wrote the letter.

You can read the meaning between the lines of the letters included in [Reflections from Prison].

Autobiographical writings of Shin Young-bok

It is a well-known fact that Mr. Shin Young-bok was sentenced to death for his involvement in the Tonghyeokdang incident and later served 20 years and 20 days as a life prisoner.

However, he has rarely mentioned in detail his feelings since he was first sentenced to death and later served a life sentence.

The [discourse] is like Shin Young-bok's autobiography, including his state of mind at the time he wrote "Memories of the Claims Court," and the reason he did not commit suicide during his long life as a life sentence prisoner.

* Memories of "Billing Memories"

"Memories of the Claims Court" is a story written by the teacher while he was on death row for nearly a year at the Namhansanseong Army Prison in 1969. It is a story about children he met in front of Jangchung Gymnasium at 5 PM on the last Saturday of every month.

This is a message written on two sheets of recycled paper given out each day, to remind me of the children who wait in front of Jangchung Gymnasium every Saturday, unaware that their teacher is in prison, and to ensure that I never forget the memories I have with those children.

The teacher said of this writing, “It was more of a recollection than a record, and it was a time of salvation, walking from the gloomy darkness of the jade room to the splendid Seooreung like azalea flowers.”

This article was discovered more than 20 years later, the year after his release.

A young man is said to have delivered it to his home. It seems to be the same military policeman who had been transferred after receiving a transfer notice and had hurriedly left a bundle of toilet paper.

Thanks to that young man, this writing was not forgotten and was included in the expanded edition of 『Reflections from Prison』 in 1998, and was later published as a book with illustrations.

* Why I didn't commit suicide

After spending a year on death row at Namhansanseong Fortress, the teacher was transferred to a civilian prison as a life sentence prisoner.

The teacher describes his 20 years in prison as “my college days,” but at the time, it was a long cave whose end was unimaginable.

An inmate who had been incarcerated for 10 years committed suicide in a prison where the teacher was.

It is said that he died after cutting his wrists in the bathroom in the middle of the night.

The prison has a clause in its [inmate compliance guidelines] that says suicide is not allowed, so this must mean that this kind of thing happens frequently.

The teacher said that he had a harsh near-death experience as a death row inmate at Namhansanseong Fortress, and that he often agonized over the 20 years he served in prison.

“Why am I serving an indefinite life sentence instead of committing suicide?”

The teacher confesses that the reason he did not commit suicide was because of the 'sunshine'.

He says that the warmth of having a newspaper-sized piece of sunlight on your lap, which lasts only two hours at most, was the pinnacle of being alive.

For the teacher, the sunlight in the winter solitary cell was the reason he lived without committing suicide, and it was life itself.

Even through the horrific near-death experience at Namhansanseong Fortress and the seemingly endless tunnel of life imprisonment, the teacher never gave up.

Rather, I learned about history, society, and humanity through it.

Mr. Shin Young-bok, who constantly reformed, changed, escaped, and protected himself like an abstraction.

That is why we call teachers the adults of this age.

20 years and 20 days of college life

It is no exaggeration to say that the teacher's understanding of humanity is the result of his long life in prison.

The teacher recounts how he walked through the lives of countless inmates in a prison where practice was eliminated, and how this gave him the ability to understand humanity and, furthermore, to reflect on himself.

Therefore, the teacher's understanding of humanity is direct and first-person.

The teacher describes his 20 years in prison as 'my college days.'

You say that the term "university years" was inspired by Maxim Gorky's "My University," but the 20 years of imprisonment that you refer to as your university years were as harsh as Gorky's arduous "university of life," and it was a world of steel that ordinary people could not even dare to imagine.

But for the teacher, solitary confinement was a philosophy classroom, and prison was a sociology classroom, a history classroom, and ultimately a anthropology classroom.

This book contains the lives of many inmates the teacher met in prison.

The story of the teacher, which features a diverse group of human figures, includes the story of the trumpeter, who burst into tears wanting to live while looking at the green barley fields, the little boy who became famous as a rice cake believer alongside the teacher, Pastor Cho who secretly ate hardtack in the middle of the night, the elderly long-term prisoners with a surprisingly flexible way of thinking that “left-leaning in theory, right-leaning in practice,” the story of the “tragic protagonist” who believes that everyone born into this world is the protagonist of their own life, and the inmate who was tormented by his conscience for donating blood mixed with water.

If in 『Reflections from Prison』 they appeared flat, in this book 『Discourse』 they come to life in three dimensions, one by one, along with the teacher's honest confession of his feelings.

It must have been difficult for the teacher to relive and relive each and every experience he had with the people he met in prison.

Yet, why does the teacher willingly share his story with us? Perhaps it's because he hopes that we, who live lives of empty theory without practice, can use his story as a crutch to stand on our own two feet and live a life of practice.

* Studying is the effort to take two steps: The story of the old carpenter Moon Do-duk

In prison, the teacher met an old carpenter with the amusing name of Moon Do-deok.

The teacher is shocked to see the carpenter's drawing of a house, which he had drawn carelessly on the ground with a wooden skewer.

A carpenter starts with the cornerstone and draws the roof last, while a teacher who has only developed his ideas through books draws the roof first.

There is a big difference between someone who practices and someone who only has theories.

Through this anecdote, the teacher points out the problem of 'tolerance', which is considered the highest level of modernization.

If you look at this picture and say, “Okay.

You draw from the cornerstone.

I draw from the roof.

If we say, “We respect each other’s differences and coexist,” then this is tolerance.

Of course, it is very important to respect differences and acknowledge diversity.

However, differences and diversity should be another starting point that leads to self-change.

Differences should not be objects of coexistence, but objects of gratitude, should be a textbook for learning, and should be the beginning of change.

If tolerance is the knowledge in your head coming down to your heart, then moving towards self-transformation is a journey of practice from your heart to your feet, an escape, and nomadism.

It is post-modern.

* The shallowness of human understanding: hypocrisy and hypocrisy

Many prison inmates have tattoos.

Tattoos are a declaration that you are a bad person, a bad tempered person.

It is hypocrisy.

It's one way for the weak to survive in this tough world.

On the contrary, hypocrisy is the clothing and disguise of the strong.

It is only what is shown on the surface, not the essence.

The red headbands we often see at protest sites are a type of tattoo.

It is a hypocritical expression of the weak showing off their unity and fighting spirit.

The court is the place for the strong.

The solemnity and quietness of the black robes contrasts sharply with the commotion at the protest site.

The problem is that hypocrisy is judged as a virtue and hypocrisy as a crime.

This is also the logic of the strong.

The logic that terrorism is destruction and murder, and war is peace and justice is the hypocrisy of the powerful.

If terrorism is the war of the weak, then war is the terrorism of the strong.

Nevertheless, our reality boldly uses the contradictory term 'war on terror'.

We must study to remove the veil of hypocrisy and falsehood.

Of course, it is nearly impossible for us to face the reality amidst the illusion created by the splendid stage and costumes, the dazzling lighting of audio and video, and the countless words.

But the greater cause of failure lies not in these devices, but in the shallowness of our human understanding.

We must blame the lack of truly human effort to evenly cultivate love and hate for humans.

Studying is a deepening of our inner self.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: April 20, 2015

- Page count, weight, size: 428 pages | 700g | 153*224*24mm

- ISBN13: 9788971996676

- ISBN10: 8971996676

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)