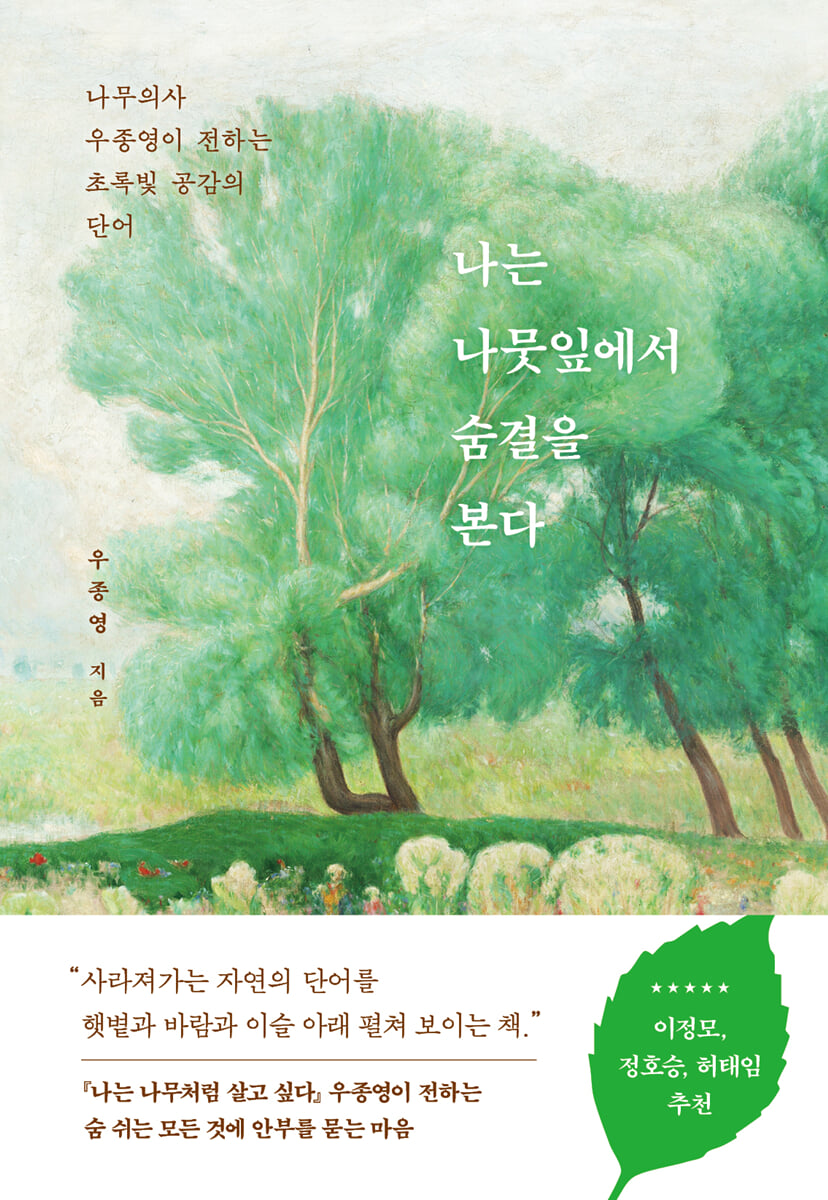

I see breath in the leaves

|

Description

Book Introduction

If we could feel the world with the heart of a bird and the gentleness of a tree,

What 'Leaf Color' and 'Sankyul' Tell Us: The closer we get, the more nature tells us.

"I See Breath in Leaves" talks about "ecological sensitivity," the empathy that sees the world through nature's eyes, in today's world where we experience the climate crisis anew every day through the warm sunlight touching our skin.

Woo Jong-young, a tree doctor who has treated tens of thousands of trees across the country for over 30 years and an author who has recorded nature's life lessons with a calm and honest attitude, walks through the forest and studies nature, and through dozens of ecological words he has collected, he awakens us to nature through the eyes of grass, flowers, birds, and foxes, breaking away from a human-centered perspective.

Woo Jong-young, who has conveyed the 'power of nature that comforts us' to numerous readers through 'I Want to Live Like a Tree', a bestseller published in 2001, and 'I Learned Life from Trees', which contains the wisdom of life he learned while caring for trees for decades, talks about 'an attitude toward life that resonates with nature' by encompassing science, philosophy, and literature and incorporating his own experiences and insights from working with the soil.

When we can live next to greenery, our lives become more colorful and rich.

This book contains the voice of the forest, which will awaken city dwellers who have forgotten nature and become absorbed in consumption.

What 'Leaf Color' and 'Sankyul' Tell Us: The closer we get, the more nature tells us.

"I See Breath in Leaves" talks about "ecological sensitivity," the empathy that sees the world through nature's eyes, in today's world where we experience the climate crisis anew every day through the warm sunlight touching our skin.

Woo Jong-young, a tree doctor who has treated tens of thousands of trees across the country for over 30 years and an author who has recorded nature's life lessons with a calm and honest attitude, walks through the forest and studies nature, and through dozens of ecological words he has collected, he awakens us to nature through the eyes of grass, flowers, birds, and foxes, breaking away from a human-centered perspective.

Woo Jong-young, who has conveyed the 'power of nature that comforts us' to numerous readers through 'I Want to Live Like a Tree', a bestseller published in 2001, and 'I Learned Life from Trees', which contains the wisdom of life he learned while caring for trees for decades, talks about 'an attitude toward life that resonates with nature' by encompassing science, philosophy, and literature and incorporating his own experiences and insights from working with the soil.

When we can live next to greenery, our lives become more colorful and rich.

This book contains the voice of the forest, which will awaken city dwellers who have forgotten nature and become absorbed in consumption.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommendation

Introduction

Chapter 1.

The highs and lows of feeling

Heart: Shaking is the default value

Empathy: Why the why is more important than the how

Notice: Don't hit, but with a warm heart

Ecological Sensitivity: To Meet You Within Me

Umwelt: If you see the world through the eyes of a tree

Empathy: Don't ask if it hurts

Laziness: Sweet Fruit

Competition: something that needs to be properly controlled and managed, like diabetes.

Pain: A mindless device for self-protection

Walking: An act of unifying the divided me.

Different: How I Make Myself

Buen Vivir: True Life

Ecological Language: A Rich Language Leads to a Rich Ecosystem

Fun: The first thing to consider when making decisions

Eye Buddha: Mother's reflection in baby's eyes

Fantasy Wandering: The End of Wandering is the Beginning of Wandering

Ecological Renaming: The Name is Half

Bioethics: Why Medicine Must Engage with Ethics

Chapter 2.

Sex, the basis of

Earth: Lonely, Terraforming

Eggplant: The result of questions and hesitation

Mountain: Resisting gravity

Baekdudaegan: The idea that mountains cannot cross water

River: Water Highway

Seasons: Natural phenomena caused by the Earth's eccentric rotation.

Microclimate: Sunny and Shady Moxibustion

Air: Why We Should Love It

Water: Poverty in the midst of plenty

The Sea: The Womb of Humanity

Wind: A hyena wandering in search of sunshine

Light: The Designer of All Things

Sound: Remembering Things That Have Gone in the Anthropocene

Size: Relative and Subjective

Earth: The Station of Living and Non-Living Things

Ecological niche: Aim for the dance

Symbiosis: A form of life where the one who loves more is not the 'one'

Interdependence: What is seen depends on what is unseen.

Evolution: What happens when you add cooperation to the desire for diversity.

Chapter 3.

Life, born by chance

The Nature of Trees: The Buddhas Among Us

Trees and Hangul: Why I'm Proud to Be Born in This Land

Gaia: Living organism

Microbes: Why Earth is a Living Planet

Body: From an object of curse to an object of service

Pet: Put me in the stroller so I can comfort you.

Companion Plants: Soothing Your Heart at the Lowest Cost

Insects: Produce, to keep producing

Bird: The beauty of flapping wings is that they leave no trace.

Homie: Grandma and Homie get smaller as time goes by.

Chapter 4.

Tae (態), made by gathering together

Me and You: Your Shadow Is Within Me

Ecosystem: Monkey Butt and Baekdu Mountain

Community: The reason there is a sense of belonging is because there is treasure there.

Commons: Do not covet sacred land.

Forest: A combination of a daycare center, playground, hospital, gym, home, and meditation center.

Eco-City: Why Toilets and Tables Are Close Together

Tidal flats: soft forests

Biotope: Children and Grasshoppers Must Live Together

Ecological Footprint: What's Lost When We Live Off Nature's Interest?

Daisy's World: Let's Make "Honeymoon" Work

Climate Change: I Believe It, But I Won't

Growth: Why Human Nature Is Looking at the Opposite Side of Truth

Purification: Let go of the reins

Chapter 5.

Receiving, receiving and giving

Gongmu Doha: My love, don't disappear.

Solomon's Ring: How to Communicate with Animals

Philosophy of Science: The Flower of Critical Thinking

Observation: The Art of Conversation

Conservation and Preservation: Overcoming the Temperature of Difference

The Elephant in the Room: The Power of Words

Mistakes: Good Mistakes, Bad Mistakes, So-So Mistakes

Hope: that they are still alive

References

Further Reading

Introduction

Chapter 1.

The highs and lows of feeling

Heart: Shaking is the default value

Empathy: Why the why is more important than the how

Notice: Don't hit, but with a warm heart

Ecological Sensitivity: To Meet You Within Me

Umwelt: If you see the world through the eyes of a tree

Empathy: Don't ask if it hurts

Laziness: Sweet Fruit

Competition: something that needs to be properly controlled and managed, like diabetes.

Pain: A mindless device for self-protection

Walking: An act of unifying the divided me.

Different: How I Make Myself

Buen Vivir: True Life

Ecological Language: A Rich Language Leads to a Rich Ecosystem

Fun: The first thing to consider when making decisions

Eye Buddha: Mother's reflection in baby's eyes

Fantasy Wandering: The End of Wandering is the Beginning of Wandering

Ecological Renaming: The Name is Half

Bioethics: Why Medicine Must Engage with Ethics

Chapter 2.

Sex, the basis of

Earth: Lonely, Terraforming

Eggplant: The result of questions and hesitation

Mountain: Resisting gravity

Baekdudaegan: The idea that mountains cannot cross water

River: Water Highway

Seasons: Natural phenomena caused by the Earth's eccentric rotation.

Microclimate: Sunny and Shady Moxibustion

Air: Why We Should Love It

Water: Poverty in the midst of plenty

The Sea: The Womb of Humanity

Wind: A hyena wandering in search of sunshine

Light: The Designer of All Things

Sound: Remembering Things That Have Gone in the Anthropocene

Size: Relative and Subjective

Earth: The Station of Living and Non-Living Things

Ecological niche: Aim for the dance

Symbiosis: A form of life where the one who loves more is not the 'one'

Interdependence: What is seen depends on what is unseen.

Evolution: What happens when you add cooperation to the desire for diversity.

Chapter 3.

Life, born by chance

The Nature of Trees: The Buddhas Among Us

Trees and Hangul: Why I'm Proud to Be Born in This Land

Gaia: Living organism

Microbes: Why Earth is a Living Planet

Body: From an object of curse to an object of service

Pet: Put me in the stroller so I can comfort you.

Companion Plants: Soothing Your Heart at the Lowest Cost

Insects: Produce, to keep producing

Bird: The beauty of flapping wings is that they leave no trace.

Homie: Grandma and Homie get smaller as time goes by.

Chapter 4.

Tae (態), made by gathering together

Me and You: Your Shadow Is Within Me

Ecosystem: Monkey Butt and Baekdu Mountain

Community: The reason there is a sense of belonging is because there is treasure there.

Commons: Do not covet sacred land.

Forest: A combination of a daycare center, playground, hospital, gym, home, and meditation center.

Eco-City: Why Toilets and Tables Are Close Together

Tidal flats: soft forests

Biotope: Children and Grasshoppers Must Live Together

Ecological Footprint: What's Lost When We Live Off Nature's Interest?

Daisy's World: Let's Make "Honeymoon" Work

Climate Change: I Believe It, But I Won't

Growth: Why Human Nature Is Looking at the Opposite Side of Truth

Purification: Let go of the reins

Chapter 5.

Receiving, receiving and giving

Gongmu Doha: My love, don't disappear.

Solomon's Ring: How to Communicate with Animals

Philosophy of Science: The Flower of Critical Thinking

Observation: The Art of Conversation

Conservation and Preservation: Overcoming the Temperature of Difference

The Elephant in the Room: The Power of Words

Mistakes: Good Mistakes, Bad Mistakes, So-So Mistakes

Hope: that they are still alive

References

Further Reading

Detailed image

.jpg)

Into the book

You should not ask which is the real oak tree.

To get a real answer, you have to start by rephrasing the question.

We must ask, "Why does an oak tree appear large in someone's Umwelt (the subjective world experienced by each individual) and small in someone else's? Why do some animals perceive an oak tree as hard and others as soft?"

If only we could ask questions like these, the world would look different.

In reality, we know very little about nature.

I'm just asking questions from a human perspective.

If you take the time to observe how the creatures you see before you sense and live, it will be truly worthwhile.

--- p.46

Sunlight sparkles through the leaves.

I'm wondering what to call this.

(…) If we were to add another word to the Korean dictionary, "leaf" (leaf-like), meaning "between leaves," then the light that sparkles between leaves would be called "leaf-like." What do you think? Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein said, "The limits of my language are the limits of my world." It's only natural that if there's no corresponding vocabulary, no concept of it would arise.

--- p.85

Air is intangible, yet it is connected in three dimensions.

It is connected horizontally and vertically, and even connects the past, present, and future through the air.

The air that was in the lungs of dinosaurs hundreds of millions of years ago is now in the rooms we live in.

The rustling of leaves in the wind means that the leaves are ready to breathe air.

The tree will breathe in the air I just exhaled.

This also means that an invisible entity connects all life.

--- p.154~155

Trees cover the earth with their unique softness, making the world green.

By being empty and not being greedy, you benefit everyone, and by pursuing both light and darkness, you exert influence equally on both the above and below ground.

(…) There are countless other characteristics of trees, but to summarize them in one word, they are special beings that filter light and provide sunlight.

They live longer than animals, do not wander around looking for food, and live in one place, so their mere presence allows countless creatures to thrive in peace.

Do you picture a tree, its roots deeply embedded in the earth, immersed in meditation like the Buddha? After all, trees are the Buddhas of our own lives.

--- p.219~220

I often have a habit of standing in front of a tree and looking at it for a long time.

Sometimes, we can accept the gestures that a tree displays as simple phenomena, and we can use the characteristics that appear in such a way as a criterion for classifying it into a species.

In this case, the tree is still just my object.

But if the tree means more than just a species, then the tree and I have some kind of relationship.

Then the tree is no longer 'it' but 'you'.

‘You’ stand facing me and become a living being and form a deep relationship with me.

Only when the relationship changes from 'I-it' to 'I-you' does the tree finally show its wounds.

Then I also discover that my shadow is reflected in the tree's wounds.

--- p.277

Who pulled the trigger on the sixth mass extinction? With human activities threatening the extinction of approximately 1,550 marine species, or 9 percent of all marine life, and analyses indicating that at least 41 percent of these threatened species are impacted by climate change, it's clear that humanity is the trigger.

Fortunately, mourning first appeared during the sixth mass extinction.

The main characters are ecologists, people who want to protect the environment, and children.

These are people who recognize that the death of all living things is like our own death.

(…) [In “Gongmu Dohaga”] If Baek Su-gwang and his wife are missing creatures, then Gwak Ri-ja is the one who clumsily writes a letter of condolences, and Yeo-ok is you, a person with a rich ecological sensitivity.

To get a real answer, you have to start by rephrasing the question.

We must ask, "Why does an oak tree appear large in someone's Umwelt (the subjective world experienced by each individual) and small in someone else's? Why do some animals perceive an oak tree as hard and others as soft?"

If only we could ask questions like these, the world would look different.

In reality, we know very little about nature.

I'm just asking questions from a human perspective.

If you take the time to observe how the creatures you see before you sense and live, it will be truly worthwhile.

--- p.46

Sunlight sparkles through the leaves.

I'm wondering what to call this.

(…) If we were to add another word to the Korean dictionary, "leaf" (leaf-like), meaning "between leaves," then the light that sparkles between leaves would be called "leaf-like." What do you think? Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein said, "The limits of my language are the limits of my world." It's only natural that if there's no corresponding vocabulary, no concept of it would arise.

--- p.85

Air is intangible, yet it is connected in three dimensions.

It is connected horizontally and vertically, and even connects the past, present, and future through the air.

The air that was in the lungs of dinosaurs hundreds of millions of years ago is now in the rooms we live in.

The rustling of leaves in the wind means that the leaves are ready to breathe air.

The tree will breathe in the air I just exhaled.

This also means that an invisible entity connects all life.

--- p.154~155

Trees cover the earth with their unique softness, making the world green.

By being empty and not being greedy, you benefit everyone, and by pursuing both light and darkness, you exert influence equally on both the above and below ground.

(…) There are countless other characteristics of trees, but to summarize them in one word, they are special beings that filter light and provide sunlight.

They live longer than animals, do not wander around looking for food, and live in one place, so their mere presence allows countless creatures to thrive in peace.

Do you picture a tree, its roots deeply embedded in the earth, immersed in meditation like the Buddha? After all, trees are the Buddhas of our own lives.

--- p.219~220

I often have a habit of standing in front of a tree and looking at it for a long time.

Sometimes, we can accept the gestures that a tree displays as simple phenomena, and we can use the characteristics that appear in such a way as a criterion for classifying it into a species.

In this case, the tree is still just my object.

But if the tree means more than just a species, then the tree and I have some kind of relationship.

Then the tree is no longer 'it' but 'you'.

‘You’ stand facing me and become a living being and form a deep relationship with me.

Only when the relationship changes from 'I-it' to 'I-you' does the tree finally show its wounds.

Then I also discover that my shadow is reflected in the tree's wounds.

--- p.277

Who pulled the trigger on the sixth mass extinction? With human activities threatening the extinction of approximately 1,550 marine species, or 9 percent of all marine life, and analyses indicating that at least 41 percent of these threatened species are impacted by climate change, it's clear that humanity is the trigger.

Fortunately, mourning first appeared during the sixth mass extinction.

The main characters are ecologists, people who want to protect the environment, and children.

These are people who recognize that the death of all living things is like our own death.

(…) [In “Gongmu Dohaga”] If Baek Su-gwang and his wife are missing creatures, then Gwak Ri-ja is the one who clumsily writes a letter of condolences, and Yeo-ok is you, a person with a rich ecological sensitivity.

--- p.348~349

Publisher's Review

Always stay fresh as is,

About the empathetic heart that holds onto the evaporating green season

The author questions the relationship between humans and other living beings and restores that connection through dozens of words grouped into five chapters: ecology, fetus, sense, number, and nature.

'Umwelt' tells us that even when staying on the same tree, a woodpecker sees an oak tree differently from a fox, and that each breathing being has its own subjective world. 'Microclimate' tells us that even the ice and snow-covered ground of a deep mountainside can be a paradise for some flowers.

The word 'san-gyeol', which is not found in the dictionary, describes "a gathering of lines that resemble waves as the mountain ridge runs along" as if forming a harmony, and 'ip-sae-bit', which means "sunlight sparkling between leaves", allows us to name the thin light we encounter while walking under the trees.

The author says that adding one ecological word to the dictionary is like adding one more species to the world.

When we call its name, its existence comes to us.

When you feel the 'breath' of that existence, you begin to care deeply about it and cherish it.

When we realize that nature is alive and breathing in such a diverse way right beside us, we might begin taking small steps today to slow the climate crisis.

When I and the green 'I-it' become 'I-you'

“How can we perceive the climate crisis as ‘our own problem’ when we don’t understand nature?” Perhaps the reason we have lost the green nature today is because we have lost the ability to empathize with nature, and thus cannot regard nature’s work as ‘our own problem.’

Ecological sensitivity is the mind that asks nature why it is in pain and carefully considers what it is telling us through its gestures.

As if listening to the story of someone close to him, the author, as a tree doctor, tries to interpret the messages conveyed by the trees and forest creatures.

The method is to lower your body and watch 'lazily' for a long time.

The author suggests that we observe what changes will occur when the nature before our eyes becomes 'you' rather than just an 'object' through ecological sensitivity.

· “It’s getting close to the end of November, but I can’t help but notice that the autumn leaves aren’t turning their beautiful colors and the leaves aren’t falling on time.

Ask the trees.

“Why on earth are you doing that?” The answer the tree gets is always the same, no matter what question you ask.

“That’s because I can’t move.” That’s right, that’s because I can’t move. That’s the same answer I gave last time when I asked why I had cut off the branch like that.

(…) Trees are beings that cannot escape even an inch from the reality they face, so they cannot help but be sensitive to climate change.

The ultimate reason why trees do not change color until late and do not shed their leaves on time is global warming.

Trees in high mountains, including the fir trees on Mt. Halla, are weakening because they have nowhere left to climb.

As the Earth gets warmer, trees' respiration increases, and they use up all the nutrients they worked hard to create during the day as they gasp for air at night.” (pp. 381-382, “Hope”)

Let's live together, whispering words of nature

Languages that stimulate human desires thrive, while those that are unprofitable or out of interest easily disappear.

Ecological language is so detached from human desires that it is easily forgotten and disappears.

If there is no language, then the being that language refers to cannot be seen.

The author says that in order to change the future, he has collected in this book 'words' about ecological empathy that we have ignored and forgotten.

To him, who has lived his entire life touching the soil, ‘soil’ is not something dirty, but rather a “station for living and non-living things,” and ‘light’ is the “designer of all things” who nurtures and refines the vast nature.

The 'air' that all living things share and breathe becomes "the reason why we must love one another," and 'coexisting' in such consideration becomes "a form of life where no matter how much we love, it never becomes '乙'."

· “The word ‘murr-ma’ in the Wagiman language, spoken by a small group of Australian Aboriginal people, means ‘the act of feeling for something in the water with one’s toes.’”

What do they find underwater? It's likely they're searching for various foods, like shellfish and seaweed, rather than lost keys.

(…) The ecosystem will survive only when language is rich.

Language is not just a combination of sounds; it is how we perceive and experience the world.

From this perspective, linguistic richness goes beyond mere lexical diversity; it is directly linked to the health of the ecosystems we inhabit.

(…) When a language disappears, not only does the knowledge and understanding of the natural world it contained disappear, but the ecosystem also disappears.” (pp. 88-89, “Ecological Language”)

Connecting your heart with the green nature

“As we explore nature, there will inevitably come a point where we must explore ourselves as a part of nature.” (Max Planck) We are all connected within the ecological system.

The author asks what changes will occur when we can imagine that plants and animals also suffer, when we know that trees, rooted deep in the ground, gasp for air because they cannot find a better place to live, and when we understand that saving them means saving ourselves.

At the end of the book's questions, the green nature around us becomes a place of coexistence where all breathing beings colorfully unfold their own lives.

· “They say that in the eyes of the Buddha, only the Buddha is visible.

The Buddha's eyes tell us how important it is for us to look at each other and have conversations.

The Buddha's eyes contain the meaning of deeply understanding and protecting the other person.

So what if we expand our eyes and turn our eyes to nature?

You can find irises in the eyes of pets and wild animals as well.

We can see ourselves, our reflections, in trees and flowers.

The morning dew that disappears the moment the sun rises is as pure as a baby's eyes.

“If you look closely at the dew, you can see yourself.” (Page 99, “Snow Buddha”)

"I See Breath in Leaves" is a "dictionary of the natural mind" that tells us that all beings breathe the same air and resonate in the ecosystem on Earth.

Empathy changes the world.

If we could see the world with the heart of a bird and the gentleness of a tree, if we could listen to nature's quiet voice and understand its suffering, we might be able to slow the climate crisis.

This book is a warm story of ecological humanities delivered by tree doctor Woo Jong-young, and is a 'word of nature whispering to us to live together' read by the author at the side of the green.

About the empathetic heart that holds onto the evaporating green season

The author questions the relationship between humans and other living beings and restores that connection through dozens of words grouped into five chapters: ecology, fetus, sense, number, and nature.

'Umwelt' tells us that even when staying on the same tree, a woodpecker sees an oak tree differently from a fox, and that each breathing being has its own subjective world. 'Microclimate' tells us that even the ice and snow-covered ground of a deep mountainside can be a paradise for some flowers.

The word 'san-gyeol', which is not found in the dictionary, describes "a gathering of lines that resemble waves as the mountain ridge runs along" as if forming a harmony, and 'ip-sae-bit', which means "sunlight sparkling between leaves", allows us to name the thin light we encounter while walking under the trees.

The author says that adding one ecological word to the dictionary is like adding one more species to the world.

When we call its name, its existence comes to us.

When you feel the 'breath' of that existence, you begin to care deeply about it and cherish it.

When we realize that nature is alive and breathing in such a diverse way right beside us, we might begin taking small steps today to slow the climate crisis.

When I and the green 'I-it' become 'I-you'

“How can we perceive the climate crisis as ‘our own problem’ when we don’t understand nature?” Perhaps the reason we have lost the green nature today is because we have lost the ability to empathize with nature, and thus cannot regard nature’s work as ‘our own problem.’

Ecological sensitivity is the mind that asks nature why it is in pain and carefully considers what it is telling us through its gestures.

As if listening to the story of someone close to him, the author, as a tree doctor, tries to interpret the messages conveyed by the trees and forest creatures.

The method is to lower your body and watch 'lazily' for a long time.

The author suggests that we observe what changes will occur when the nature before our eyes becomes 'you' rather than just an 'object' through ecological sensitivity.

· “It’s getting close to the end of November, but I can’t help but notice that the autumn leaves aren’t turning their beautiful colors and the leaves aren’t falling on time.

Ask the trees.

“Why on earth are you doing that?” The answer the tree gets is always the same, no matter what question you ask.

“That’s because I can’t move.” That’s right, that’s because I can’t move. That’s the same answer I gave last time when I asked why I had cut off the branch like that.

(…) Trees are beings that cannot escape even an inch from the reality they face, so they cannot help but be sensitive to climate change.

The ultimate reason why trees do not change color until late and do not shed their leaves on time is global warming.

Trees in high mountains, including the fir trees on Mt. Halla, are weakening because they have nowhere left to climb.

As the Earth gets warmer, trees' respiration increases, and they use up all the nutrients they worked hard to create during the day as they gasp for air at night.” (pp. 381-382, “Hope”)

Let's live together, whispering words of nature

Languages that stimulate human desires thrive, while those that are unprofitable or out of interest easily disappear.

Ecological language is so detached from human desires that it is easily forgotten and disappears.

If there is no language, then the being that language refers to cannot be seen.

The author says that in order to change the future, he has collected in this book 'words' about ecological empathy that we have ignored and forgotten.

To him, who has lived his entire life touching the soil, ‘soil’ is not something dirty, but rather a “station for living and non-living things,” and ‘light’ is the “designer of all things” who nurtures and refines the vast nature.

The 'air' that all living things share and breathe becomes "the reason why we must love one another," and 'coexisting' in such consideration becomes "a form of life where no matter how much we love, it never becomes '乙'."

· “The word ‘murr-ma’ in the Wagiman language, spoken by a small group of Australian Aboriginal people, means ‘the act of feeling for something in the water with one’s toes.’”

What do they find underwater? It's likely they're searching for various foods, like shellfish and seaweed, rather than lost keys.

(…) The ecosystem will survive only when language is rich.

Language is not just a combination of sounds; it is how we perceive and experience the world.

From this perspective, linguistic richness goes beyond mere lexical diversity; it is directly linked to the health of the ecosystems we inhabit.

(…) When a language disappears, not only does the knowledge and understanding of the natural world it contained disappear, but the ecosystem also disappears.” (pp. 88-89, “Ecological Language”)

Connecting your heart with the green nature

“As we explore nature, there will inevitably come a point where we must explore ourselves as a part of nature.” (Max Planck) We are all connected within the ecological system.

The author asks what changes will occur when we can imagine that plants and animals also suffer, when we know that trees, rooted deep in the ground, gasp for air because they cannot find a better place to live, and when we understand that saving them means saving ourselves.

At the end of the book's questions, the green nature around us becomes a place of coexistence where all breathing beings colorfully unfold their own lives.

· “They say that in the eyes of the Buddha, only the Buddha is visible.

The Buddha's eyes tell us how important it is for us to look at each other and have conversations.

The Buddha's eyes contain the meaning of deeply understanding and protecting the other person.

So what if we expand our eyes and turn our eyes to nature?

You can find irises in the eyes of pets and wild animals as well.

We can see ourselves, our reflections, in trees and flowers.

The morning dew that disappears the moment the sun rises is as pure as a baby's eyes.

“If you look closely at the dew, you can see yourself.” (Page 99, “Snow Buddha”)

"I See Breath in Leaves" is a "dictionary of the natural mind" that tells us that all beings breathe the same air and resonate in the ecosystem on Earth.

Empathy changes the world.

If we could see the world with the heart of a bird and the gentleness of a tree, if we could listen to nature's quiet voice and understand its suffering, we might be able to slow the climate crisis.

This book is a warm story of ecological humanities delivered by tree doctor Woo Jong-young, and is a 'word of nature whispering to us to live together' read by the author at the side of the green.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 25, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 396 pages | 534g | 145*210*25mm

- ISBN13: 9788965967354

- ISBN10: 896596735X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)