Philosophizing about death

|

Description

Book Introduction

Everything about life and death in one volume

To be alive, to die, to kill

Philosophical Arguments on Life, Existence, and Death

The weight of death determined by the value of life

The second title in the Antares Humanities Planning Series, “Reading Philosophy with the Heart,” following “Philosophy of Anxiety.”

This is a philosophical book that concludes the debate on 'death'.

The author, Steven Luper, is a professor of philosophy at Trinity College, a prestigious American humanities school. He began teaching 'death' before Professor Shelly Kagan of Yale University, who is well-known in Korea for 'DEATH', and has continued to do so. He is a true 'death expert' philosopher.

If Professor Kagan's introductory book stirred up the social atmosphere that made discussing death taboo, Professor Rufer's book, "The Philosophy of Death," as its title suggests, jumps into the middle of the debate on "death" and confronts it head-on.

After establishing the meaning of 'being alive', it deals with 'death', 'murder', 'suicide', 'euthanasia', and even 'fetal killing (abortion)', a topic that most philosophers avoid.

It persistently delves into the rationality and morality of 'being alive', 'dying', 'killing', 'dying oneself', and 'dying at the hands of others'.

Although death is thoroughly considered in the language of reason, it is based on a heartwarming love for humanity.

“We are mortal beings who will inevitably die someday, so the more we understand death, the more courage we gain to face life,” he emphasizes, and like the saying “A good life leaves a bad death behind,” he also delivers a weighty message that “the weight of death is ultimately determined by the value of life.”

To be alive, to die, to kill

Philosophical Arguments on Life, Existence, and Death

The weight of death determined by the value of life

The second title in the Antares Humanities Planning Series, “Reading Philosophy with the Heart,” following “Philosophy of Anxiety.”

This is a philosophical book that concludes the debate on 'death'.

The author, Steven Luper, is a professor of philosophy at Trinity College, a prestigious American humanities school. He began teaching 'death' before Professor Shelly Kagan of Yale University, who is well-known in Korea for 'DEATH', and has continued to do so. He is a true 'death expert' philosopher.

If Professor Kagan's introductory book stirred up the social atmosphere that made discussing death taboo, Professor Rufer's book, "The Philosophy of Death," as its title suggests, jumps into the middle of the debate on "death" and confronts it head-on.

After establishing the meaning of 'being alive', it deals with 'death', 'murder', 'suicide', 'euthanasia', and even 'fetal killing (abortion)', a topic that most philosophers avoid.

It persistently delves into the rationality and morality of 'being alive', 'dying', 'killing', 'dying oneself', and 'dying at the hands of others'.

Although death is thoroughly considered in the language of reason, it is based on a heartwarming love for humanity.

“We are mortal beings who will inevitably die someday, so the more we understand death, the more courage we gain to face life,” he emphasizes, and like the saying “A good life leaves a bad death behind,” he also delivers a weighty message that “the weight of death is ultimately determined by the value of life.”

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction: The Irreversible Interruption of the Life Process

Part 1_DYING

Chapter 1: Being Alive

Life and Living Beings | Humanity, Personhood, and Identity

Chapter 2: Dying

Aging, Termination, Cessation of Life, and the Cessation of Existence | The Standard of Death

Chapter 3: Debates on Death

Symmetry Argument | The Problem of Perspective | The Path to Peace

Chapter 4: Mortal Harm

The Calculative Value of Life | Harmful Thesis

Chapter 5: When is death harmful?

Epicurus' Challenge | Five Times When Death Becomes Bad

Part 2_KILLING

Chapter 6: Killing

Harmful Explanation | Subject Value Explanation | Agreement Explanation | Combination Explanation

Chapter 7: Dying by Oneself and Dying by the Hands of Another

Suicide and Euthanasia | Rationally Chosen Death | Morally Chosen Death | Preventing or Assisting

Chapter 8: The Dilemma of Fetal Murder

Arguments Against Abortion | Arguments for Abortion | The Only Death Difficult to Solve Philosophically

main

References

Search

Part 1_DYING

Chapter 1: Being Alive

Life and Living Beings | Humanity, Personhood, and Identity

Chapter 2: Dying

Aging, Termination, Cessation of Life, and the Cessation of Existence | The Standard of Death

Chapter 3: Debates on Death

Symmetry Argument | The Problem of Perspective | The Path to Peace

Chapter 4: Mortal Harm

The Calculative Value of Life | Harmful Thesis

Chapter 5: When is death harmful?

Epicurus' Challenge | Five Times When Death Becomes Bad

Part 2_KILLING

Chapter 6: Killing

Harmful Explanation | Subject Value Explanation | Agreement Explanation | Combination Explanation

Chapter 7: Dying by Oneself and Dying by the Hands of Another

Suicide and Euthanasia | Rationally Chosen Death | Morally Chosen Death | Preventing or Assisting

Chapter 8: The Dilemma of Fetal Murder

Arguments Against Abortion | Arguments for Abortion | The Only Death Difficult to Solve Philosophically

main

References

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

We feel we must take some action in the present because we take for granted that we will continue to exist in the future.

This is why I believe that living each busy day diligently will be helpful to my 'future self'.

My future self is ultimately my present self.

At the same time, my future self is like a child that I raise and care for.

We all want that child to be happy in the future, to become a person we can be proud of, and to remember his or her past with warmth.

But much of what we do today only makes sense when that child grows and thrives.

If extinction, the disappearance of our very existence, were to occur, all this planning and care would become meaningless.

There is nothing to look forward to in life.

Since there is no future self to care for, there is no reason to continue doing what I consider important now, and there is nothing new to challenge.

What good is it if the very existence of 'I' disappears completely?

So if death means extinction, then for most of us, death is a very bad thing.

---From "Introduction: The Irreversible Interruption of the Life Process"

For a being to be said to be alive, it must have considerable ability to sustain itself.

However, this does not mean that self-maintenance is achieved in any way.

The self-maintenance of living organisms is controlled by persistent replicators.

These replicators can reproduce themselves, mutate, and pass those mutations on to the next generation.

Only when an entity has the ability to repeat the process of maintaining itself under the control of a continuous replicator within it can we say that entity is a living being.

---From "Chapter 1: Being Alive"

We often say that we are “always dying,” but death is a distinct concept from aging.

Aging is the process by which our bodies gradually lose their ability to regenerate and maintain themselves, partly as a result of cellular senescence.

Somatic cells have a genetically pre-designed limit called the Hayflick limit, which, when reached, causes the body to lose its ability to regenerate and maintain itself.

These aged cells die more easily, usually through necrosis, a "messy" way in which the cell bursts and damages surrounding tissue, or apoptosis, a "clean" way in which the cell cleans up after itself.

Apoptosis is a normal process inherent in the growth and maintenance of the body.

---From "Chapter 2: Dying"

If death is to be harmful to the dead entity, there must be a 'subject' who suffers harm because of the death, the 'content' of the harm must be clear, and there must be a 'time point' when the harm occurs.

The key here is 'point of view'.

In other words, when is death bad?

What harm can there be if we are dead and gone?

If we consider the 'timing' of this harm, there are only two possible cases, since death follows immediately after life ends.

One is that death harms while we are alive, and the other is that death harms us after we die.

---From "Chapter 3: Debates on Death"

Some things can be 'overall' good or bad for us.

This means that it can be good or bad for us, taking all the circumstances into account.

If something happens and our lives become better than they would have been if it hadn't happened, then overall, that event is good for us.

If something happened and our lives would have been better if it hadn't happened, but it did and made things worse, then the event was bad for us overall.

On the other hand, when we say that something is 'overall' good or bad, there will also be things that are 'partially' good or bad.

For example, let's say you're shipwrecked and you drink salty seawater to quench your thirst.

It may be 'partially' beneficial as it may quench your thirst for a while, but 'overall' it will be detrimental to your health.

While increasing the intrinsically good things in our lives or reducing the inherently bad things may be seen as partially beneficial, what really matters is the overall benefit.

Because 'partial' benefits often end up being detrimental to us 'overall'.

---From "Chapter 4: Mortal Harm"

Death is harmful to us beyond time.

Death is harmful to us throughout our lives precisely because it makes our lives worse than if we had not died.

However, it is not that there is no plausible solution to the question of perspective.

Unlike 'eternalism', which holds that we suffer mortal harm forever, 'postmortemism', which holds that we suffer harm after we die, and 'indeterminism', which holds that we cannot precisely specify the point in time when we suffer mortal harm because the concept of a blurred boundary exists, 'antecedentism' holds that we suffer mortal harm while we are alive, that is, while we possess the benefits that death deprives us of.

Events after death are equally detrimental to our interests while alive.

Another solution, 'simultaneity', holds that we suffer mortal harm while we are dying, which is also a reasonable view.

However, this perspective does not explain when we are harmed by events after death.

---From "Chapter 5: When is Death Harmful?"

Determining whether an action is wrong is a rather complex matter.

If certain characteristics are directed toward wrongdoing, it may strongly suggest that the action is wrong.

Conversely, some characteristics may indicate that the behavior is not wrong.

Whether an action is wrong or not must be judged by comprehensively examining all of these characteristics.

Even if an act has characteristics that constitute wrongdoing, it may not be wrong in the aggregate.

But if you have that kind of trait, then that action is 'first of all' wrong.

So instead of asking, “Why is murder wrong?” I want to ask, “What is it about murder that makes it ‘prima facie wrong’?”

---From "Chapter 6: Killing"

When and how should we die? It might be perfectly reasonable to fight to the end against a fatal illness or injury.

When life itself is at stake, seeking aggressive medical treatment, including pain medications to reduce suffering, is sometimes the best option.

But that's not always the case.

For some people, it may be better to refuse life-sustaining treatment and accept death on their own.

For others, especially those whose lives are not directly threatened but whose quality of life is so severely impaired that it is beyond recovery, a more aggressive option may be the best option.

This is why I believe that living each busy day diligently will be helpful to my 'future self'.

My future self is ultimately my present self.

At the same time, my future self is like a child that I raise and care for.

We all want that child to be happy in the future, to become a person we can be proud of, and to remember his or her past with warmth.

But much of what we do today only makes sense when that child grows and thrives.

If extinction, the disappearance of our very existence, were to occur, all this planning and care would become meaningless.

There is nothing to look forward to in life.

Since there is no future self to care for, there is no reason to continue doing what I consider important now, and there is nothing new to challenge.

What good is it if the very existence of 'I' disappears completely?

So if death means extinction, then for most of us, death is a very bad thing.

---From "Introduction: The Irreversible Interruption of the Life Process"

For a being to be said to be alive, it must have considerable ability to sustain itself.

However, this does not mean that self-maintenance is achieved in any way.

The self-maintenance of living organisms is controlled by persistent replicators.

These replicators can reproduce themselves, mutate, and pass those mutations on to the next generation.

Only when an entity has the ability to repeat the process of maintaining itself under the control of a continuous replicator within it can we say that entity is a living being.

---From "Chapter 1: Being Alive"

We often say that we are “always dying,” but death is a distinct concept from aging.

Aging is the process by which our bodies gradually lose their ability to regenerate and maintain themselves, partly as a result of cellular senescence.

Somatic cells have a genetically pre-designed limit called the Hayflick limit, which, when reached, causes the body to lose its ability to regenerate and maintain itself.

These aged cells die more easily, usually through necrosis, a "messy" way in which the cell bursts and damages surrounding tissue, or apoptosis, a "clean" way in which the cell cleans up after itself.

Apoptosis is a normal process inherent in the growth and maintenance of the body.

---From "Chapter 2: Dying"

If death is to be harmful to the dead entity, there must be a 'subject' who suffers harm because of the death, the 'content' of the harm must be clear, and there must be a 'time point' when the harm occurs.

The key here is 'point of view'.

In other words, when is death bad?

What harm can there be if we are dead and gone?

If we consider the 'timing' of this harm, there are only two possible cases, since death follows immediately after life ends.

One is that death harms while we are alive, and the other is that death harms us after we die.

---From "Chapter 3: Debates on Death"

Some things can be 'overall' good or bad for us.

This means that it can be good or bad for us, taking all the circumstances into account.

If something happens and our lives become better than they would have been if it hadn't happened, then overall, that event is good for us.

If something happened and our lives would have been better if it hadn't happened, but it did and made things worse, then the event was bad for us overall.

On the other hand, when we say that something is 'overall' good or bad, there will also be things that are 'partially' good or bad.

For example, let's say you're shipwrecked and you drink salty seawater to quench your thirst.

It may be 'partially' beneficial as it may quench your thirst for a while, but 'overall' it will be detrimental to your health.

While increasing the intrinsically good things in our lives or reducing the inherently bad things may be seen as partially beneficial, what really matters is the overall benefit.

Because 'partial' benefits often end up being detrimental to us 'overall'.

---From "Chapter 4: Mortal Harm"

Death is harmful to us beyond time.

Death is harmful to us throughout our lives precisely because it makes our lives worse than if we had not died.

However, it is not that there is no plausible solution to the question of perspective.

Unlike 'eternalism', which holds that we suffer mortal harm forever, 'postmortemism', which holds that we suffer harm after we die, and 'indeterminism', which holds that we cannot precisely specify the point in time when we suffer mortal harm because the concept of a blurred boundary exists, 'antecedentism' holds that we suffer mortal harm while we are alive, that is, while we possess the benefits that death deprives us of.

Events after death are equally detrimental to our interests while alive.

Another solution, 'simultaneity', holds that we suffer mortal harm while we are dying, which is also a reasonable view.

However, this perspective does not explain when we are harmed by events after death.

---From "Chapter 5: When is Death Harmful?"

Determining whether an action is wrong is a rather complex matter.

If certain characteristics are directed toward wrongdoing, it may strongly suggest that the action is wrong.

Conversely, some characteristics may indicate that the behavior is not wrong.

Whether an action is wrong or not must be judged by comprehensively examining all of these characteristics.

Even if an act has characteristics that constitute wrongdoing, it may not be wrong in the aggregate.

But if you have that kind of trait, then that action is 'first of all' wrong.

So instead of asking, “Why is murder wrong?” I want to ask, “What is it about murder that makes it ‘prima facie wrong’?”

---From "Chapter 6: Killing"

When and how should we die? It might be perfectly reasonable to fight to the end against a fatal illness or injury.

When life itself is at stake, seeking aggressive medical treatment, including pain medications to reduce suffering, is sometimes the best option.

But that's not always the case.

For some people, it may be better to refuse life-sustaining treatment and accept death on their own.

For others, especially those whose lives are not directly threatened but whose quality of life is so severely impaired that it is beyond recovery, a more aggressive option may be the best option.

---From "Chapter 7: Dying by Oneself and Dying at the Hands of Another"

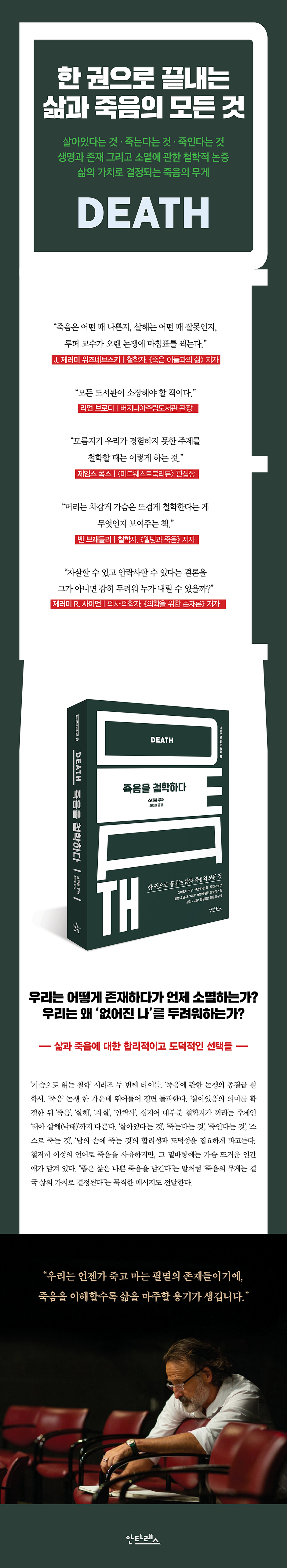

Publisher's Review

How do we come into existence and when do we disappear?

Why are we afraid of the 'disappeared self'?

Rational and moral choices about life and death

A social atmosphere has been created in which we can talk about death with greater candor than before.

Many people now express their opinions on euthanasia and assisted death (physician-assisted suicide), which were previously difficult to talk about.

The abortion law has become virtually meaningless.

Perhaps because the concept has become somewhat clearer, we no longer blindly treat death as a taboo.

Still, hearing the word 'death' doesn't give me a very good feeling.

Still, most of us conjure up feelings of anxiety, fear, and loss.

It goes without saying that we all die someday.

We are mortal beings who move towards death from the moment we are born.

This fact sometimes casts a dark shadow over our lives.

But paradoxically, the truth that all living beings are mortal fuels our will to live better.

Death takes away the good things from us, but it also takes away the bad things.

So death can be either bad or good for us.

In other words, for death to be bad, we must live better lives.

The more I philosophize about death, the more I find myself looking back on life.

Epicurus's provocation: Death is nothing.

The philosophical debate about death was sparked by this passage from Epicurus, the ancient Greek philosopher known to us as 'hedonist', in his Letter to Menoeceus (Epistol? Pros Menoikea).

“Death is actually nothing to us.

As long as we ourselves exist, death has nothing to do with us.

When death comes for us, we are already gone.

So, whether we are alive or dead, death has nothing to do with us.

“Because when we are alive there is no death, and when we are dead there is no us.”

Epicurus confronted our fear of death head-on with this simple yet powerful argument.

His argument against the 'harm thesis' that death is harmful to us was this:

For something to harm us, the 'subject' of the harm, the 'content' of the harm, and the 'time' when the harm occurs must be clear.

According to him, there are only two times when death can be said to be harmful: while we are alive and after we die.

However, since dead people no longer exist, it is difficult to address these three points.

Once you die, there is no subject called 'I' who will be harmed, so death cannot be said to be bad. Conversely, while you are alive, there is clearly a subject who will be harmed, but since you have not yet died, there is no way to explain what harm death does to that subject.

This is why Epicurus argued that death is not a bad thing at all.

At first glance, Epicurus' argument seems perfect and even comforting.

That is understandable, as the ultimate goal of Epicurean philosophy was to help us find ataraxia, or peace of mind.

This is also why the argument was made that death is not harmful to us.

The fear of death is Ataraxia's biggest obstacle, so he would have wanted to remove it.

But no matter how hard I try, thinking about death makes me uncomfortable.

This is our intuition.

In fact, what we fear is not 'death' but 'loss of life', but Epicurus cleverly avoided that point.

―Asymmetry of Time: Why is it okay for me to be ‘nonexistent’, but I don’t like the ‘me that will not exist’?

Lucretius, a Roman philosopher who followed Epicurus, went a step further and asked an interesting question.

This is the so-called 'symmetry argument'.

He told us to think about the 'non-existent me' before we were born.

No one would feel anxiety or pain over the non-existence of that past.

So, the logic was that there was no reason to fear the non-existence of the 'non-existent self' after death, which was the opposite of it.

But this 'symmetry argument' immediately ran into strong objections.

This is none other than the 'asymmetry argument' that non-existence before birth and non-existence after death are different.

What this means is that not being born and not existing are essentially different from not existing after death.

Our lives and interests are fundamentally 'future' oriented.

Our plans, our goals, our hopes, our loves all stretch toward the time to come.

We want life to continue into the future rather than extending it into the past and being born earlier.

Moreover, death, crucially, takes away the 'good life' we could have enjoyed had we lived longer, but it never took anything away from our non-existence before birth.

Birth is only the 'beginning' of good things to come, but death is the 'end' of good things we have enjoyed so far and will enjoy in the future.

Nevertheless, the ancient philosophical view that death does not harm us at all sharply reveals not only our attitude toward death, but also the fundamental psychology of human existence, which experiences time and lives with an orientation toward the future.

The more you fear death, the more you perceive death negatively, the more you think about life.

Is our fear of death really just an irrational illusion?

The Harm of Loss and Deprivation: Being 'Dead' Isn't Bad

Professor Steven Rufer explains why Epicurus' provocative arguments and sophisticated logic fail to fully convince us.

Because our fundamental fear of death is not an irrational emotion, but a rational and natural response that stems from our attachment to life.

The more you have to lose, the greater the pain of loss.

The more valuable life is, the more fearful death is.

The real reason death is bad for us is not because being dead is painful.

It is bad because it 'deprives' us of the good things we would have enjoyed if we were alive.

The real harm that death inflicts is that we are forever deprived of the opportunity to enjoy all the valuable things we would have experienced if we had not died: love, friendship, accomplishments, happiness, beautiful scenery, delicious food.

Of course, death doesn't only take away good things.

As the author points out, death takes away both good and bad things.

For someone suffering from irreversible pain, death may actually be a good thing by taking away that pain.

There is a saying that “a good life leaves a bad death.”

The more valuable and rich life is, the more we lose in death.

If you have lived a miserable life, you have little to lose by dying, but if you have lived a full life, death is that much more harmful.

As Professor Ruper puts it, “my future self is like a child that I raise and care for.”

We strive to live better in the present, hoping that the child will become a happy and proud person.

But death destroys the very existence of that ‘future self.’

If the child I've been caring for disappears, all the planning and care I've put in up to this point will become meaningless.

This perspective completely changes our thinking about death.

Because it shifts the issue of death from the mystery of ‘after death’ to the value of ‘while alive.’

This leads to the profound insight that the weight of death is determined by how we cultivate our lives.

So here we come to another question.

If our lives were no longer filled with anything good and were filled only with terrible suffering, what would death mean to us then?

The Two Faces of Death: Death is a Mirror of Life

Death takes away from us both the good life and the bad life.

Like the two sides of a coin, death has two faces.

The other side of the coin is that when life itself becomes unbearable suffering, we must also realize that death can actually be a salvation from harm.

Through this, we learn that the value of life is never absolute.

Life can be quite awful sometimes.

Think of situations like the grief of losing all your loved ones, a disease that leaves you with nothing but endless pain, or dementia that causes you to lose your memory.

In the sense that it frees us from this suffering, death may actually be a 'good thing' for us.

This discussion leads us to the very difficult and sensitive philosophical question of suicide and euthanasia.

If continuing to live is absolutely against our interests—if, in other words, living is nothing but a continuation of suffering—wouldn't a painless death be a rational and moral choice? Professor Rufer also addresses these issues head-on, as they arise at the very edge of life.

So, all the discussions in this book lead us to ask ourselves the most fundamental questions.

“What determines the value of life?”

“What is a life worth living?”

The effort to find the answer to this question will be a process of realizing the true meaning of our lives reflected in the mirror of death.

We do not philosophize about death in order to become immersed in death itself.

―The Weight of Death: The better life is, the heavier death becomes.

The weight of death is proportional to the value of life.

At the end of a trivial life, a light death awaits us, and at the summit of a valuable life, a heavy death awaits us.

This book covers everything about life and death, beginning with Epicurus' provocative claim that death is nothing.

What we have covered here is only a very small part.

It delves deeply into the meaning of 'being alive', 'dying', 'killing', and even 'dying oneself' and 'dying at the hands of others'.

Philosophy often appears at first glance to be a relentless analysis of a question, but a closer look reveals that it is not far removed from our lives.

Although this book, "Philosophy of Death," seems to delve into death solely through the language of reason, it contains a heartwarming love for humanity at its core.

We are mortal beings who will inevitably die someday, so the more we understand death, the more courage we gain to face life.

Ultimately, what we encounter at the end of this philosophical journey is not ‘death’ but ‘life’.

It is an attempt to find answers to the meaning and value of how to fill our limited, one-time life.

Because there is a clear end called death, every moment, every relationship, every experience of life given to us becomes more precious and meaningful.

This is the greatest paradox that death presents to us.

If death is bad because it deprives us of the good things we would have enjoyed while alive, why not, instead of simply fearing such a death, make our lives better by completely establishing death as something worse and more burdensome?

Why are we afraid of the 'disappeared self'?

Rational and moral choices about life and death

A social atmosphere has been created in which we can talk about death with greater candor than before.

Many people now express their opinions on euthanasia and assisted death (physician-assisted suicide), which were previously difficult to talk about.

The abortion law has become virtually meaningless.

Perhaps because the concept has become somewhat clearer, we no longer blindly treat death as a taboo.

Still, hearing the word 'death' doesn't give me a very good feeling.

Still, most of us conjure up feelings of anxiety, fear, and loss.

It goes without saying that we all die someday.

We are mortal beings who move towards death from the moment we are born.

This fact sometimes casts a dark shadow over our lives.

But paradoxically, the truth that all living beings are mortal fuels our will to live better.

Death takes away the good things from us, but it also takes away the bad things.

So death can be either bad or good for us.

In other words, for death to be bad, we must live better lives.

The more I philosophize about death, the more I find myself looking back on life.

Epicurus's provocation: Death is nothing.

The philosophical debate about death was sparked by this passage from Epicurus, the ancient Greek philosopher known to us as 'hedonist', in his Letter to Menoeceus (Epistol? Pros Menoikea).

“Death is actually nothing to us.

As long as we ourselves exist, death has nothing to do with us.

When death comes for us, we are already gone.

So, whether we are alive or dead, death has nothing to do with us.

“Because when we are alive there is no death, and when we are dead there is no us.”

Epicurus confronted our fear of death head-on with this simple yet powerful argument.

His argument against the 'harm thesis' that death is harmful to us was this:

For something to harm us, the 'subject' of the harm, the 'content' of the harm, and the 'time' when the harm occurs must be clear.

According to him, there are only two times when death can be said to be harmful: while we are alive and after we die.

However, since dead people no longer exist, it is difficult to address these three points.

Once you die, there is no subject called 'I' who will be harmed, so death cannot be said to be bad. Conversely, while you are alive, there is clearly a subject who will be harmed, but since you have not yet died, there is no way to explain what harm death does to that subject.

This is why Epicurus argued that death is not a bad thing at all.

At first glance, Epicurus' argument seems perfect and even comforting.

That is understandable, as the ultimate goal of Epicurean philosophy was to help us find ataraxia, or peace of mind.

This is also why the argument was made that death is not harmful to us.

The fear of death is Ataraxia's biggest obstacle, so he would have wanted to remove it.

But no matter how hard I try, thinking about death makes me uncomfortable.

This is our intuition.

In fact, what we fear is not 'death' but 'loss of life', but Epicurus cleverly avoided that point.

―Asymmetry of Time: Why is it okay for me to be ‘nonexistent’, but I don’t like the ‘me that will not exist’?

Lucretius, a Roman philosopher who followed Epicurus, went a step further and asked an interesting question.

This is the so-called 'symmetry argument'.

He told us to think about the 'non-existent me' before we were born.

No one would feel anxiety or pain over the non-existence of that past.

So, the logic was that there was no reason to fear the non-existence of the 'non-existent self' after death, which was the opposite of it.

But this 'symmetry argument' immediately ran into strong objections.

This is none other than the 'asymmetry argument' that non-existence before birth and non-existence after death are different.

What this means is that not being born and not existing are essentially different from not existing after death.

Our lives and interests are fundamentally 'future' oriented.

Our plans, our goals, our hopes, our loves all stretch toward the time to come.

We want life to continue into the future rather than extending it into the past and being born earlier.

Moreover, death, crucially, takes away the 'good life' we could have enjoyed had we lived longer, but it never took anything away from our non-existence before birth.

Birth is only the 'beginning' of good things to come, but death is the 'end' of good things we have enjoyed so far and will enjoy in the future.

Nevertheless, the ancient philosophical view that death does not harm us at all sharply reveals not only our attitude toward death, but also the fundamental psychology of human existence, which experiences time and lives with an orientation toward the future.

The more you fear death, the more you perceive death negatively, the more you think about life.

Is our fear of death really just an irrational illusion?

The Harm of Loss and Deprivation: Being 'Dead' Isn't Bad

Professor Steven Rufer explains why Epicurus' provocative arguments and sophisticated logic fail to fully convince us.

Because our fundamental fear of death is not an irrational emotion, but a rational and natural response that stems from our attachment to life.

The more you have to lose, the greater the pain of loss.

The more valuable life is, the more fearful death is.

The real reason death is bad for us is not because being dead is painful.

It is bad because it 'deprives' us of the good things we would have enjoyed if we were alive.

The real harm that death inflicts is that we are forever deprived of the opportunity to enjoy all the valuable things we would have experienced if we had not died: love, friendship, accomplishments, happiness, beautiful scenery, delicious food.

Of course, death doesn't only take away good things.

As the author points out, death takes away both good and bad things.

For someone suffering from irreversible pain, death may actually be a good thing by taking away that pain.

There is a saying that “a good life leaves a bad death.”

The more valuable and rich life is, the more we lose in death.

If you have lived a miserable life, you have little to lose by dying, but if you have lived a full life, death is that much more harmful.

As Professor Ruper puts it, “my future self is like a child that I raise and care for.”

We strive to live better in the present, hoping that the child will become a happy and proud person.

But death destroys the very existence of that ‘future self.’

If the child I've been caring for disappears, all the planning and care I've put in up to this point will become meaningless.

This perspective completely changes our thinking about death.

Because it shifts the issue of death from the mystery of ‘after death’ to the value of ‘while alive.’

This leads to the profound insight that the weight of death is determined by how we cultivate our lives.

So here we come to another question.

If our lives were no longer filled with anything good and were filled only with terrible suffering, what would death mean to us then?

The Two Faces of Death: Death is a Mirror of Life

Death takes away from us both the good life and the bad life.

Like the two sides of a coin, death has two faces.

The other side of the coin is that when life itself becomes unbearable suffering, we must also realize that death can actually be a salvation from harm.

Through this, we learn that the value of life is never absolute.

Life can be quite awful sometimes.

Think of situations like the grief of losing all your loved ones, a disease that leaves you with nothing but endless pain, or dementia that causes you to lose your memory.

In the sense that it frees us from this suffering, death may actually be a 'good thing' for us.

This discussion leads us to the very difficult and sensitive philosophical question of suicide and euthanasia.

If continuing to live is absolutely against our interests—if, in other words, living is nothing but a continuation of suffering—wouldn't a painless death be a rational and moral choice? Professor Rufer also addresses these issues head-on, as they arise at the very edge of life.

So, all the discussions in this book lead us to ask ourselves the most fundamental questions.

“What determines the value of life?”

“What is a life worth living?”

The effort to find the answer to this question will be a process of realizing the true meaning of our lives reflected in the mirror of death.

We do not philosophize about death in order to become immersed in death itself.

―The Weight of Death: The better life is, the heavier death becomes.

The weight of death is proportional to the value of life.

At the end of a trivial life, a light death awaits us, and at the summit of a valuable life, a heavy death awaits us.

This book covers everything about life and death, beginning with Epicurus' provocative claim that death is nothing.

What we have covered here is only a very small part.

It delves deeply into the meaning of 'being alive', 'dying', 'killing', and even 'dying oneself' and 'dying at the hands of others'.

Philosophy often appears at first glance to be a relentless analysis of a question, but a closer look reveals that it is not far removed from our lives.

Although this book, "Philosophy of Death," seems to delve into death solely through the language of reason, it contains a heartwarming love for humanity at its core.

We are mortal beings who will inevitably die someday, so the more we understand death, the more courage we gain to face life.

Ultimately, what we encounter at the end of this philosophical journey is not ‘death’ but ‘life’.

It is an attempt to find answers to the meaning and value of how to fill our limited, one-time life.

Because there is a clear end called death, every moment, every relationship, every experience of life given to us becomes more precious and meaningful.

This is the greatest paradox that death presents to us.

If death is bad because it deprives us of the good things we would have enjoyed while alive, why not, instead of simply fearing such a death, make our lives better by completely establishing death as something worse and more burdensome?

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: October 30, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 476 pages | 616g | 145*210*24mm

- ISBN13: 9791191742329

- ISBN10: 1191742326

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)