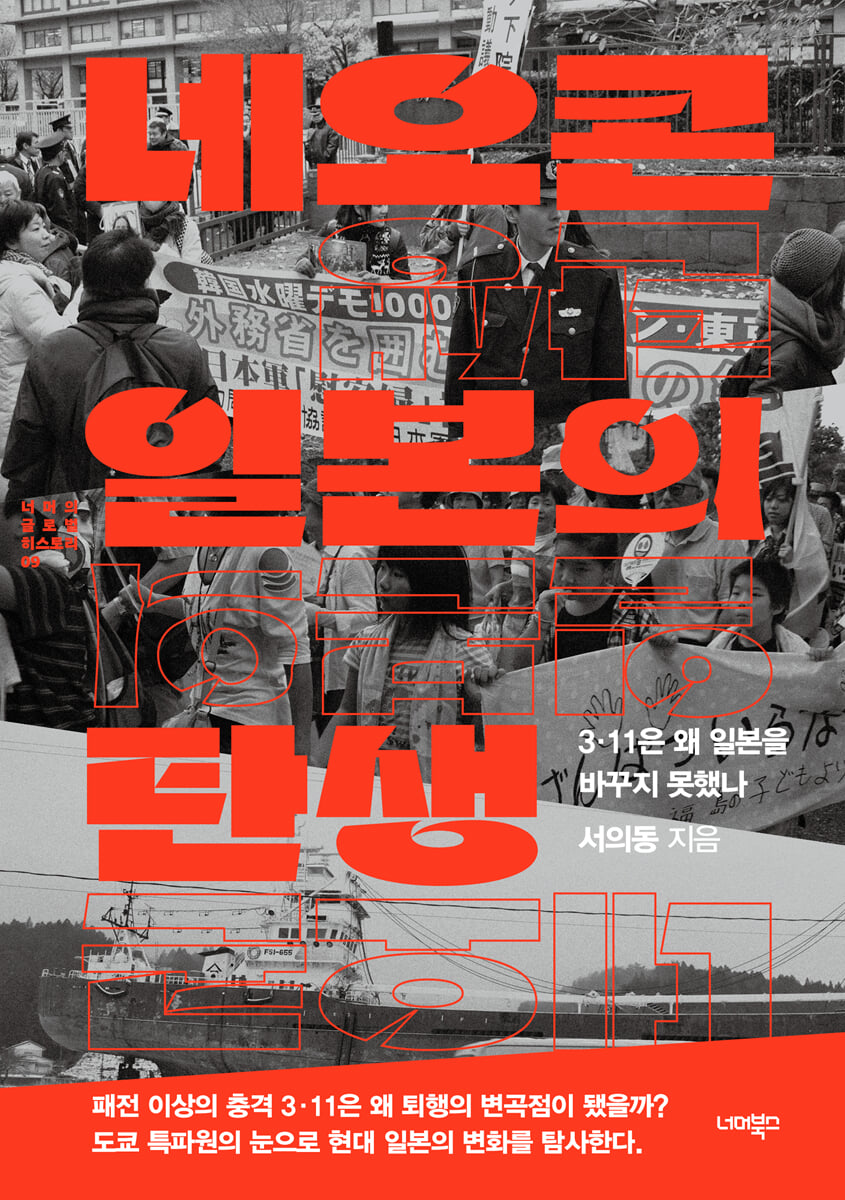

The Birth of Neocon Japan

|

Description

Book Introduction

Special Project for the 60th Anniversary of the Korea-Japan Agreement

Where is 'Neocon Japan' headed?

"The Birth of Neoconservative Japan" refers to the conservative right-wing group represented by Shinzo Abe as "neoconservatives" and dissects the process of rightward shift in Japanese society through their unstoppable dominance.

The turning point was the Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima nuclear power plant accident on March 11, 2011 (hereinafter referred to as 3/11).

Why did Japanese society choose the "regression" of a neoconservative government instead of addressing the causes of March 11th and moving toward a new future? Why did March 11th become the turning point of this regression? This book is a vivid investigative report and an attempt to answer these questions by journalist Seo Ui-dong, who witnessed the critical three years from March 11th to Abe's rise to power, which shaped the current Japan.

This book begins by turning back the clock 20 years to March 11th and examining the crisis and instability in post-Cold War Japan, and the process by which a right-wing shift developed within it.

Since the end of the Cold War in the 1990s, the conflict surrounding Japan's future path has culminated in the neoliberalism of Junichiro Koizumi, the welfareism of Yukio Hatoyama, and the neoconservatism of Shinzo Abe.

Abe sought to transform Japan from a "one-nation pacifist" nation into an "Indo-Pacific" strategic nation capable of designing its own chessboard.

The author said that the main motivation for writing the book was to examine the background and process of the enormous changes taking place in neighboring Japan since the 1990s.

The March 11th incident occurred five days after the author took up his post as a correspondent, and the story of his four-day coverage of the Sendai tsunami, risking exposure to the atomic bomb, along with various interviews and photographs over the past three years, adds to the vividness of the book.

Seo Ui-dong believes that in relations between nations, a balance of dignity and emotions is just as important as a balance of interests.

Properly remembering and passing on the wrongdoings of the aggressor nation in the past is the foundational task of balancing respect and emotion, and is emphasized as the "minimum principle" of Korea-Japan relations.

Examining the profound changes in contemporary Japanese society through "The Birth of Neoconservative Japan" will also provide many insights into the current right-wing tendencies and direction of our society.

This is the ninth book in Beyond Books' 'Beyond Global History' series.

Where is 'Neocon Japan' headed?

"The Birth of Neoconservative Japan" refers to the conservative right-wing group represented by Shinzo Abe as "neoconservatives" and dissects the process of rightward shift in Japanese society through their unstoppable dominance.

The turning point was the Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima nuclear power plant accident on March 11, 2011 (hereinafter referred to as 3/11).

Why did Japanese society choose the "regression" of a neoconservative government instead of addressing the causes of March 11th and moving toward a new future? Why did March 11th become the turning point of this regression? This book is a vivid investigative report and an attempt to answer these questions by journalist Seo Ui-dong, who witnessed the critical three years from March 11th to Abe's rise to power, which shaped the current Japan.

This book begins by turning back the clock 20 years to March 11th and examining the crisis and instability in post-Cold War Japan, and the process by which a right-wing shift developed within it.

Since the end of the Cold War in the 1990s, the conflict surrounding Japan's future path has culminated in the neoliberalism of Junichiro Koizumi, the welfareism of Yukio Hatoyama, and the neoconservatism of Shinzo Abe.

Abe sought to transform Japan from a "one-nation pacifist" nation into an "Indo-Pacific" strategic nation capable of designing its own chessboard.

The author said that the main motivation for writing the book was to examine the background and process of the enormous changes taking place in neighboring Japan since the 1990s.

The March 11th incident occurred five days after the author took up his post as a correspondent, and the story of his four-day coverage of the Sendai tsunami, risking exposure to the atomic bomb, along with various interviews and photographs over the past three years, adds to the vividness of the book.

Seo Ui-dong believes that in relations between nations, a balance of dignity and emotions is just as important as a balance of interests.

Properly remembering and passing on the wrongdoings of the aggressor nation in the past is the foundational task of balancing respect and emotion, and is emphasized as the "minimum principle" of Korea-Japan relations.

Examining the profound changes in contemporary Japanese society through "The Birth of Neoconservative Japan" will also provide many insights into the current right-wing tendencies and direction of our society.

This is the ninth book in Beyond Books' 'Beyond Global History' series.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Prologue_Japan's Inflection Point 3?11

Part 1: Post-Cold War and the Gulf War

Chapter 1: Japan's Chaos in the 1990s

1 The Gulf War: 'Paid for and got slapped in the face'

2 The chaos after the bubble burst

3. Stripped bare by 'comfort women'

Chapter 2: The 'Pivot to Asia' Ends in Failure

1 Hatoyama Visits Yu Gwan-sun's Prison Cell

2 Okinawa, the 'Graveyard of the Democratic Party'

3. The short spring days of Korea-Japan relations

Chapter 3: Japan's Loss of Brakes

1 The left that failed to overcome the imperial system

2 Why Did the Socialist Party Fall?

Part 2: The Unlocked Right-Wingers

Chapter 4: How They Became 'Victims'

1 “Japanese kidnapped”, bomb thrown by Kim Jong-il

2 Collision between Coast Guard and Chinese fishing boats

3 From San Francisco to the Senkakus: The Politics of Territorial Disputes

Chapter 5: Historical Revisionism, the Internet Right, and Anti-Koreanism

1. Yoshinori Kobayashi's "Gomanimism"

2 Kono's Statement and the 'New Rebellion'

3. Net Right and Anti-Korean Rhetoric

Chapter 6: The Right-Wingers Who Shake Up Japanese Politics

1 Hashimoto, who grew up eating Kansai's frustrations

2. Right-wing signboard, "Sun Tribe" Ishihara

3 Abe, the 'neoconservative darling'

Part 3 Japan after 3/11

Chapter 7: Why Didn't 3?11 Change Japan?

1 The Great Earthquake That Destroyed the Democratic Party

2 The Unfulfilled 'Hydrangea Revolution'

3 “Let’s revive the glory of Showa”

Chapter 8: The Neocon Abe Era

1. Bureaucracy is over.

2 Japan's abandonment of the Peace Constitution

3 “No more apologies”

Chapter 9: Japan Dreams of a Strategic Nation

1. The US is tying the 'Indo-Pacific' together, followed by Japan.

2 The US-Japan Alliance, a 'national system'

Chapter 10: Where is Northeast Asia headed?

1 Japan's Rush to Become a Security State

2 Japan's 'Semiconductor Rise' and the Acheson Line

Epilogue

Search

Part 1: Post-Cold War and the Gulf War

Chapter 1: Japan's Chaos in the 1990s

1 The Gulf War: 'Paid for and got slapped in the face'

2 The chaos after the bubble burst

3. Stripped bare by 'comfort women'

Chapter 2: The 'Pivot to Asia' Ends in Failure

1 Hatoyama Visits Yu Gwan-sun's Prison Cell

2 Okinawa, the 'Graveyard of the Democratic Party'

3. The short spring days of Korea-Japan relations

Chapter 3: Japan's Loss of Brakes

1 The left that failed to overcome the imperial system

2 Why Did the Socialist Party Fall?

Part 2: The Unlocked Right-Wingers

Chapter 4: How They Became 'Victims'

1 “Japanese kidnapped”, bomb thrown by Kim Jong-il

2 Collision between Coast Guard and Chinese fishing boats

3 From San Francisco to the Senkakus: The Politics of Territorial Disputes

Chapter 5: Historical Revisionism, the Internet Right, and Anti-Koreanism

1. Yoshinori Kobayashi's "Gomanimism"

2 Kono's Statement and the 'New Rebellion'

3. Net Right and Anti-Korean Rhetoric

Chapter 6: The Right-Wingers Who Shake Up Japanese Politics

1 Hashimoto, who grew up eating Kansai's frustrations

2. Right-wing signboard, "Sun Tribe" Ishihara

3 Abe, the 'neoconservative darling'

Part 3 Japan after 3/11

Chapter 7: Why Didn't 3?11 Change Japan?

1 The Great Earthquake That Destroyed the Democratic Party

2 The Unfulfilled 'Hydrangea Revolution'

3 “Let’s revive the glory of Showa”

Chapter 8: The Neocon Abe Era

1. Bureaucracy is over.

2 Japan's abandonment of the Peace Constitution

3 “No more apologies”

Chapter 9: Japan Dreams of a Strategic Nation

1. The US is tying the 'Indo-Pacific' together, followed by Japan.

2 The US-Japan Alliance, a 'national system'

Chapter 10: Where is Northeast Asia headed?

1 Japan's Rush to Become a Security State

2 Japan's 'Semiconductor Rise' and the Acheson Line

Epilogue

Search

Into the book

The issue of contamination and exposure due to the massive release of radioactive materials when the reactor 'melts down' was a subject of reporting and an 'existential' issue.

Three days after the Great East Japan Earthquake, I left Tokyo in a rental car and headed to Miyagi Prefecture, an area hit by the tsunami.

The original goal was Iwate Prefecture, north of Miyagi Prefecture, and the navigation system predicted that it would take 6 hours, but the earthquake damaged many roads heading north, so it took 20 hours just to get to Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture.

It was already two days ago when the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Unit 1 had exploded and radioactive material was leaking in earnest, but the weather was so hot that I drove with the windows open, and as the sun set on the way, I had to stay overnight at a hotel in Fukushima City.

The purpose of the business trip was to cover the devastation caused by the tsunami, and since I was driving a rental car myself, I couldn't focus on the progress of the nuclear accident.

Their knowledge of nuclear power plants and radiation was so limited that they did not question the Japanese government spokesperson (Chief Cabinet Secretary)’s statement that “there will be no immediate health impact from the radiation leak.”

Above all, at the time, we could not have guessed how big of a disaster the Fukushima nuclear accident would be.

During my four days covering the tsunami, additional explosions occurred at the nuclear power plant, and the fear of nuclear power and radiation became a reality as the leaked radioactive material was carried by the wind and contaminated a water purification plant in Tokyo.

It has become a habit to carefully check the country of origin when buying bottled water or going grocery shopping.

Although the mental burden was less than that of my fellow correspondents because it was a solo assignment, I continued to feel ‘nervous.’

My heart sank every time the Russian-made radiation dosimeter I carried with me on a business trip to Fukushima to write a special feature article beeped.

--- p.9

3/11 was expected to be a "decisive moment" that would open the door to reform after fundamentally reflecting on the very nature of Japan's existence as a nation.

3?11 was to be the new era demarcation line that would replace Japan's defeat on August 15, 1945.

Immediately after 3/11, the Japanese newspapers began using the coined word "Jae-hu" (災後), meaning "after the Great East Japan Earthquake," instead of "Jeon-hu," which was an abbreviation for "after the defeat in World War II."

After the nuclear accident, Japan's new future was presented as a "small and safe country" that would break away from great power politics.

There were also voices demanding accountability for the media's reporting on nuclear power plants.

There is essentially no difference between reporting the announcements of the Imperial General Headquarters, which concealed the unfavorable situation at the end of the Pacific War, without verification, and transcribing the propaganda of the power company that “nuclear power plants are safe” without verification.

But in less than two years, Japanese society returned to "normalcy" without any meaningful change, and tilted toward the right, fueled by historical revisionism and nationalism.

Despite the shock of defeat, why did we choose a rapid 'regression' instead of eliminating the cause and moving toward a new future?

Why did March 11th become a turning point for regression?

This book is an attempt to find an answer to this question.

--- p.11~12

Former Sungkonghoe University professor Kwon Hyuk-tae believes that the phenomenon of fragmented individuals wandering in search of a safe haven through "self-discovery" due to the emergence of a consumer society driven by rapid economic growth in the 1990s ultimately led to them entrusting themselves to the "state."

The new network of relationships created by the informatization of the 1990s, combined with subcultures such as comics, animation, and games, has become the basis of a new nationalism in which fragmented and wealthy individuals have turned to the community of Japan as a sanctuary for their lives.

For them, the post-war period, symbolized by peace, democracy, and high economic growth, was a grand narrative that defined their lives, but it was also a story of a ‘different world’ unrelated to their ‘endless daily life.’

For Akagi and Amamiya, who live in this world, democracy, civil movements, and human rights were dull words they could only encounter at school, and they developed hostility toward the leftists who used such language and pretended to be cool.

--- p.36

Japan created a 'victim identity' through the innocent victims of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki just before its defeat in World War II.

As Japan's defeat and the occupation by the Allied Powers General Headquarters (GHQ) destroyed Japan's identity as an "emperor-based family state," postwar Japan had to find a new identity.

During this period of confusion, they attempted to build a collective identity of “war victims = Japanese people” by mobilizing and rearranging the emotions of the atomic bomb victims’ suffering.

However, this victim identity could not avoid the 'logical disqualification' of not being able to identify the perpetrator.

Unlike Germany, which established victimhood by setting up the Nazis as the perpetrators, Japan was in a position where it could not point out the United States or even imperial fascism as the perpetrators.

Because Japan was unable to condemn the use of the atomic bomb by the United States and to self-criticize its war of aggression, it was unable to avoid the emptiness of its "atomic bomb victim identity" by "dehistoricizing" the tragedy of the bombing into a universal wish for peace for humanity.

It was a natural consequence that postwar pacifism based on this identity had difficulty taking firm root in Japanese society.

Then, in 2002, I had a crucial opportunity to stand in the shoes of a victim who had an offender.

North Korean leader Kim Jong-il's official admission of the abduction of Japanese nationals in the 1970s and 1980s allowed Japan to obtain the identity of the victims, enabling it to identify the perpetrators for the first time since the war.

--- p.110~115

The person who captivated the younger generation during this period was the cartoonist Yoshinori Kobayashi.

Kobayashi began to preach a right-wing view of history with the "Gomaism Declaration" in 1992, and solidified his position as a right-wing thinker in 1998 by publishing "On War," which supports wars of aggression and advocates for the possession of military forces.

He calls the Japanese who participated in Japan's war of aggression in the first half of the 20th century "grandfather."

The past imperialist wars are elevated to the 'passion' of our grandfathers for justice.

By replacing the cause of the war started by our grandfathers with personal sentiments such as “for the sake of loved ones, for the sake of family,” we block critical thinking.

--- p.139

For the Japanese, the Great East Japan Earthquake was a shock comparable to their defeat in World War II.

Historian Yonaha Jun commented, “The earthquake seemed to have dragged Japan back into the chaos immediately following its defeat, cruelly tearing apart the languid daily life of the ‘late postwar period’ that seemed destined to last forever.”

Cultural critic Tsunehiro Uno described the Japanese people's feelings after the nuclear accident as a feeling that something "human-created, yet beyond human control, is eating away at our living world from within," making them live "daily lives imbued with an extraordinary tension."

Haruki Wada, Professor Emeritus of the University of Tokyo, said, “If August 15th was a time when we stopped the war we started ourselves and lived in peace from now on, now is the time when those who have collapsed under the power of nature and doubled the misfortune with their foolishness rise from the depths of that pain and call for a new coexistence with nature.”

It was seen as the end of the 'postwar period' that began with Emperor Showa's declaration of the end of the war on August 15, 1945.

Historian of science Yoshitaka Yamamoto said that the nuclear accident “marked the end of the illusion of science and technology that had dominated Japan for 150 years since the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and the Meiji Restoration.”

The Great East Japan Earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear accident came to symbolize a dividing line between one era and the beginning of a new one.

Three days after the Great East Japan Earthquake, I left Tokyo in a rental car and headed to Miyagi Prefecture, an area hit by the tsunami.

The original goal was Iwate Prefecture, north of Miyagi Prefecture, and the navigation system predicted that it would take 6 hours, but the earthquake damaged many roads heading north, so it took 20 hours just to get to Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture.

It was already two days ago when the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Unit 1 had exploded and radioactive material was leaking in earnest, but the weather was so hot that I drove with the windows open, and as the sun set on the way, I had to stay overnight at a hotel in Fukushima City.

The purpose of the business trip was to cover the devastation caused by the tsunami, and since I was driving a rental car myself, I couldn't focus on the progress of the nuclear accident.

Their knowledge of nuclear power plants and radiation was so limited that they did not question the Japanese government spokesperson (Chief Cabinet Secretary)’s statement that “there will be no immediate health impact from the radiation leak.”

Above all, at the time, we could not have guessed how big of a disaster the Fukushima nuclear accident would be.

During my four days covering the tsunami, additional explosions occurred at the nuclear power plant, and the fear of nuclear power and radiation became a reality as the leaked radioactive material was carried by the wind and contaminated a water purification plant in Tokyo.

It has become a habit to carefully check the country of origin when buying bottled water or going grocery shopping.

Although the mental burden was less than that of my fellow correspondents because it was a solo assignment, I continued to feel ‘nervous.’

My heart sank every time the Russian-made radiation dosimeter I carried with me on a business trip to Fukushima to write a special feature article beeped.

--- p.9

3/11 was expected to be a "decisive moment" that would open the door to reform after fundamentally reflecting on the very nature of Japan's existence as a nation.

3?11 was to be the new era demarcation line that would replace Japan's defeat on August 15, 1945.

Immediately after 3/11, the Japanese newspapers began using the coined word "Jae-hu" (災後), meaning "after the Great East Japan Earthquake," instead of "Jeon-hu," which was an abbreviation for "after the defeat in World War II."

After the nuclear accident, Japan's new future was presented as a "small and safe country" that would break away from great power politics.

There were also voices demanding accountability for the media's reporting on nuclear power plants.

There is essentially no difference between reporting the announcements of the Imperial General Headquarters, which concealed the unfavorable situation at the end of the Pacific War, without verification, and transcribing the propaganda of the power company that “nuclear power plants are safe” without verification.

But in less than two years, Japanese society returned to "normalcy" without any meaningful change, and tilted toward the right, fueled by historical revisionism and nationalism.

Despite the shock of defeat, why did we choose a rapid 'regression' instead of eliminating the cause and moving toward a new future?

Why did March 11th become a turning point for regression?

This book is an attempt to find an answer to this question.

--- p.11~12

Former Sungkonghoe University professor Kwon Hyuk-tae believes that the phenomenon of fragmented individuals wandering in search of a safe haven through "self-discovery" due to the emergence of a consumer society driven by rapid economic growth in the 1990s ultimately led to them entrusting themselves to the "state."

The new network of relationships created by the informatization of the 1990s, combined with subcultures such as comics, animation, and games, has become the basis of a new nationalism in which fragmented and wealthy individuals have turned to the community of Japan as a sanctuary for their lives.

For them, the post-war period, symbolized by peace, democracy, and high economic growth, was a grand narrative that defined their lives, but it was also a story of a ‘different world’ unrelated to their ‘endless daily life.’

For Akagi and Amamiya, who live in this world, democracy, civil movements, and human rights were dull words they could only encounter at school, and they developed hostility toward the leftists who used such language and pretended to be cool.

--- p.36

Japan created a 'victim identity' through the innocent victims of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki just before its defeat in World War II.

As Japan's defeat and the occupation by the Allied Powers General Headquarters (GHQ) destroyed Japan's identity as an "emperor-based family state," postwar Japan had to find a new identity.

During this period of confusion, they attempted to build a collective identity of “war victims = Japanese people” by mobilizing and rearranging the emotions of the atomic bomb victims’ suffering.

However, this victim identity could not avoid the 'logical disqualification' of not being able to identify the perpetrator.

Unlike Germany, which established victimhood by setting up the Nazis as the perpetrators, Japan was in a position where it could not point out the United States or even imperial fascism as the perpetrators.

Because Japan was unable to condemn the use of the atomic bomb by the United States and to self-criticize its war of aggression, it was unable to avoid the emptiness of its "atomic bomb victim identity" by "dehistoricizing" the tragedy of the bombing into a universal wish for peace for humanity.

It was a natural consequence that postwar pacifism based on this identity had difficulty taking firm root in Japanese society.

Then, in 2002, I had a crucial opportunity to stand in the shoes of a victim who had an offender.

North Korean leader Kim Jong-il's official admission of the abduction of Japanese nationals in the 1970s and 1980s allowed Japan to obtain the identity of the victims, enabling it to identify the perpetrators for the first time since the war.

--- p.110~115

The person who captivated the younger generation during this period was the cartoonist Yoshinori Kobayashi.

Kobayashi began to preach a right-wing view of history with the "Gomaism Declaration" in 1992, and solidified his position as a right-wing thinker in 1998 by publishing "On War," which supports wars of aggression and advocates for the possession of military forces.

He calls the Japanese who participated in Japan's war of aggression in the first half of the 20th century "grandfather."

The past imperialist wars are elevated to the 'passion' of our grandfathers for justice.

By replacing the cause of the war started by our grandfathers with personal sentiments such as “for the sake of loved ones, for the sake of family,” we block critical thinking.

--- p.139

For the Japanese, the Great East Japan Earthquake was a shock comparable to their defeat in World War II.

Historian Yonaha Jun commented, “The earthquake seemed to have dragged Japan back into the chaos immediately following its defeat, cruelly tearing apart the languid daily life of the ‘late postwar period’ that seemed destined to last forever.”

Cultural critic Tsunehiro Uno described the Japanese people's feelings after the nuclear accident as a feeling that something "human-created, yet beyond human control, is eating away at our living world from within," making them live "daily lives imbued with an extraordinary tension."

Haruki Wada, Professor Emeritus of the University of Tokyo, said, “If August 15th was a time when we stopped the war we started ourselves and lived in peace from now on, now is the time when those who have collapsed under the power of nature and doubled the misfortune with their foolishness rise from the depths of that pain and call for a new coexistence with nature.”

It was seen as the end of the 'postwar period' that began with Emperor Showa's declaration of the end of the war on August 15, 1945.

Historian of science Yoshitaka Yamamoto said that the nuclear accident “marked the end of the illusion of science and technology that had dominated Japan for 150 years since the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and the Meiji Restoration.”

The Great East Japan Earthquake and the Fukushima nuclear accident came to symbolize a dividing line between one era and the beginning of a new one.

--- p.209~210

Publisher's Review

Japan's turning point: March 11th

The author described Japan, which he observed for three years as a correspondent since 2011, as a time of political and social chaos and upheaval reminiscent of the period following World War II, with blurred vision due to the dust of upheaval.

March 11th was an event that heightened the Japanese people's anxiety to the max.

From immediately after the incident until the end of 2012, Japan was in a state of 'interregnum' (a period of absence of authority) where the substance of a new order was not clear, similar to the period after our 'December 3' civil war.

However, the tectonic shift brought about by March 11 created a space in which neoconservatives could take power.

While the Democratic Party, including the Social Democratic Party, lacked the leadership to lead it to the left, it was full of energy to lead it to the right.

Ultimately, the Democratic Party's short three-year term in power failed, and at the end of 2012, a political group with neoconservatism and historical revisionism as its identity, represented by Abe, came to the forefront.

This book, divided into three parts, begins by examining the circumstances in which Japan, faced with a crisis in the international community after the Gulf War in the 1990s, advocated for the theory of a normal nation that violated its pacifist constitution, and felt anxiety and bewilderment as it confronted issues of the past, while political forces such as the Democratic Party and the Socialist Party failed to present alternatives. It then examines the events and process in which neoconservatism emerged in earnest and Japanese society shifted to the right.

Historical Revisionism, Internet Right, and Anti-Koreanism as Psychological Mechanisms of Right-Wing Shift

It may be difficult for younger readers to grasp, but Japan's postwar prosperity reached its peak in the late 1980s.

At that time, many experts predicted that Japan would soon surpass the United States.

But the Japanese economy collapsed as soon as this prediction was made, and Japanese society, which had been dominated by cosmopolitanism until the 1980s, was suddenly engulfed in an identity crisis.

This book vividly portrays the chaos of 1990s Japan, including the anxiety and bewilderment of the Japanese people who were confronted with unsealed historical issues just as the economic bubble burst.

The political and economic turmoil has hit the younger generation hard.

The gaping gap in society is putting pressure on young people, and the number of young people turning to nationalism and the right wing is increasing.

A comic-like subculture seduced young people.

This book examines the process by which right-wing cartoonist Yoshinori Kobayashi popularized historical revisionism, the textbook war of the New History Textbook Making Association (Saeyokmo), and the rise of online right-wingers and anti-Korean sentiment.

In particular, the influence of Yoshinori Kobayashi's manga "On War" on the younger generation was enormous.

Young people were enthusiastic about this cartoon, which affirmed the Greater East Asia War and even argued for the need to have an army.

Now, things like peace, democracy, and high growth have become stories from another world, unrelated to their daily lives.

Democracy, civil rights, and human rights were just empty words I encountered in school, and I grew to harbor hostility toward the leftists who used such language and pretended to be cool.

Taking advantage of this gap, the right-wing movement, which argued that the pre-war history had been distorted by the US military and that Japan's modern history should be re-examined in a way that would increase national pride, gained strength as the "New Rebellion Movement."

Japan's 'mistakes' have been revealed through historical issues such as the Japanese military comfort women and the Nanjing Massacre, but the new generation in Japan has not learned about such past history in school.

Rather than seriously confronting and reflecting on past mistakes, Japanese society chose a roundabout path by mobilizing the frame of nationalism.

The Decline of the Japanese Left After the Cold War

The Democratic Party's rise to power in 2009 was merely an interlude in Japan's overall conservatism following the end of the Cold War.

In the 1990s, Japan experienced a prolonged recession and frequent conflicts over past history and territorial disputes with neighboring countries, leading to the consolidation of the conservative right wing.

The center-right Democratic Party government needed to join forces with the left to change Japan's course, but Japan's left-wing politics began to lose its presence after peaking in the late 1980s.

Although the Socialist Party had no chance of taking power, it played a role in protecting Japan's "constitutional pacifism" during the Cold War by securing a barrier to constitutional revision.

However, in the cohabitation system of the Liberal Democratic Party and the Socialist Party, which was a shortened version of the East-West conflict, the Socialist Party was complacent as a 'perennial opposition party', and in the mid-1990s, when the long-term ruling LDP system collapsed due to a money scandal, the Socialist Party also fell along with it in the political realignment.

After forming a coalition government with the Liberal Democratic Party, he lost his identity as a "constitutional pacifist" by making a 180-degree turn in his previous stance on the Japan-US Security Treaty, the Rising Sun Flag, the Kimigayo, and the Self-Defense Forces.

Even in the media, the influence of international cooperation-oriented newspapers such as the Asahi Shimbun has been steadily weakening.

When the issue of North Korea's abduction of Japanese citizens was confirmed to be true in 2002, progressive left-wing public opinion was shocked.

The second shock came in 2014 when the Asahi Shimbun, which had been active in raising the issue of Japanese military "comfort women," retracted its initial comfort women report, which unverified Yoshida Seiji's claim that military comfort women were forcibly taken from Jeju Island, calling it an incorrect article.

The overall conservative shift in the media landscape has ultimately contributed significantly to Abe's long-term monopoly.

With the total collapse of the left, the political and ideological base to counter the historical revisionism and rightward shift that began in earnest in the late 1990s disappeared.

March 11 and the Expansion of Neoconservative Power

Since the end of the Cold War in the 1990s, Japan has been mired in an identity crisis.

As the Cold War structure disintegrated, a sense of anxiety gripped the Japanese, as if they had been thrown into the middle of the international community.

As the international political front of the anti-communist alliance disappeared in East Asia, the movement to hold people accountable for the sealed past emerged with the issue of the "Japanese military comfort women," which served as an opportunity to reaffirm the hypocrisy of Japan's "closed pacifism" built without an apology, reflection, or settlement of the past.

The comfort women issue has gone beyond the level of relations between Korea and Japan and has been elevated to a common international agenda as a problem of "wartime sexual violence."

The shock brought about by the past served as an opportunity to unite the conservative right wing in Japan, and Japan's nationalistic nationalism began to grow amid this identity anxiety.

North Korea's admission of Japanese abductions in 2002 transformed Japan from a perpetrator into a victim, and in the process, Abe emerged as a key figure of neoconservatism.

It also spread the desire for a "strong Japan" by causing disputes such as the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands in Chinese) dispute between China and Japan and the territorial dispute between Korea and Dokdo.

Japan was helpless in the face of 3/11.

In the meantime, Japan's status in the international community collapsed in an instant.

A new vision of a "small and safe country" was presented, and voices criticizing the nuclear mafia and advocating for nuclear phase-out erupted, but ultimately, these voices were defeated in their confrontation with the retrograde growth-oriented policies represented by Abe.

The Democratic Party, which was in power at the time, attempted to pursue a nuclear phase-out policy, but was thwarted by US restraint, and was forced to resign after three years and three months, failing to impress during the disaster recovery process.

"The Birth of Neoconservative Japan" examines the process by which Abe, after returning to power, established a "prime ministerial dictatorship" system and nullified the Peace Constitution, as well as the significance of the declaration made on the 70th anniversary of the end of the war that "Japan will no longer apologize to other countries" from the perspective of Korea-Japan relations.

We examine how the revision of the US-Japan Defense Cooperation Guidelines, known as the 2015 Guidelines, and its subsequent measures, such as the enactment and revision of security legislation, have transformed Japan into a country capable of launching war on its own initiative.

This paper examines the process by which Abe, who sought to transform Japan into a strategic nation, created the geopolitical concept of the "Indo-Pacific," and its significance within the context of strengthening the "US-Japan alliance."

In addition, we examine Japan's recently aggressively pursued strategy to revitalize the semiconductor industry, along with its mandatory security measures, in the context of Korea-Japan relations.

The author described Japan, which he observed for three years as a correspondent since 2011, as a time of political and social chaos and upheaval reminiscent of the period following World War II, with blurred vision due to the dust of upheaval.

March 11th was an event that heightened the Japanese people's anxiety to the max.

From immediately after the incident until the end of 2012, Japan was in a state of 'interregnum' (a period of absence of authority) where the substance of a new order was not clear, similar to the period after our 'December 3' civil war.

However, the tectonic shift brought about by March 11 created a space in which neoconservatives could take power.

While the Democratic Party, including the Social Democratic Party, lacked the leadership to lead it to the left, it was full of energy to lead it to the right.

Ultimately, the Democratic Party's short three-year term in power failed, and at the end of 2012, a political group with neoconservatism and historical revisionism as its identity, represented by Abe, came to the forefront.

This book, divided into three parts, begins by examining the circumstances in which Japan, faced with a crisis in the international community after the Gulf War in the 1990s, advocated for the theory of a normal nation that violated its pacifist constitution, and felt anxiety and bewilderment as it confronted issues of the past, while political forces such as the Democratic Party and the Socialist Party failed to present alternatives. It then examines the events and process in which neoconservatism emerged in earnest and Japanese society shifted to the right.

Historical Revisionism, Internet Right, and Anti-Koreanism as Psychological Mechanisms of Right-Wing Shift

It may be difficult for younger readers to grasp, but Japan's postwar prosperity reached its peak in the late 1980s.

At that time, many experts predicted that Japan would soon surpass the United States.

But the Japanese economy collapsed as soon as this prediction was made, and Japanese society, which had been dominated by cosmopolitanism until the 1980s, was suddenly engulfed in an identity crisis.

This book vividly portrays the chaos of 1990s Japan, including the anxiety and bewilderment of the Japanese people who were confronted with unsealed historical issues just as the economic bubble burst.

The political and economic turmoil has hit the younger generation hard.

The gaping gap in society is putting pressure on young people, and the number of young people turning to nationalism and the right wing is increasing.

A comic-like subculture seduced young people.

This book examines the process by which right-wing cartoonist Yoshinori Kobayashi popularized historical revisionism, the textbook war of the New History Textbook Making Association (Saeyokmo), and the rise of online right-wingers and anti-Korean sentiment.

In particular, the influence of Yoshinori Kobayashi's manga "On War" on the younger generation was enormous.

Young people were enthusiastic about this cartoon, which affirmed the Greater East Asia War and even argued for the need to have an army.

Now, things like peace, democracy, and high growth have become stories from another world, unrelated to their daily lives.

Democracy, civil rights, and human rights were just empty words I encountered in school, and I grew to harbor hostility toward the leftists who used such language and pretended to be cool.

Taking advantage of this gap, the right-wing movement, which argued that the pre-war history had been distorted by the US military and that Japan's modern history should be re-examined in a way that would increase national pride, gained strength as the "New Rebellion Movement."

Japan's 'mistakes' have been revealed through historical issues such as the Japanese military comfort women and the Nanjing Massacre, but the new generation in Japan has not learned about such past history in school.

Rather than seriously confronting and reflecting on past mistakes, Japanese society chose a roundabout path by mobilizing the frame of nationalism.

The Decline of the Japanese Left After the Cold War

The Democratic Party's rise to power in 2009 was merely an interlude in Japan's overall conservatism following the end of the Cold War.

In the 1990s, Japan experienced a prolonged recession and frequent conflicts over past history and territorial disputes with neighboring countries, leading to the consolidation of the conservative right wing.

The center-right Democratic Party government needed to join forces with the left to change Japan's course, but Japan's left-wing politics began to lose its presence after peaking in the late 1980s.

Although the Socialist Party had no chance of taking power, it played a role in protecting Japan's "constitutional pacifism" during the Cold War by securing a barrier to constitutional revision.

However, in the cohabitation system of the Liberal Democratic Party and the Socialist Party, which was a shortened version of the East-West conflict, the Socialist Party was complacent as a 'perennial opposition party', and in the mid-1990s, when the long-term ruling LDP system collapsed due to a money scandal, the Socialist Party also fell along with it in the political realignment.

After forming a coalition government with the Liberal Democratic Party, he lost his identity as a "constitutional pacifist" by making a 180-degree turn in his previous stance on the Japan-US Security Treaty, the Rising Sun Flag, the Kimigayo, and the Self-Defense Forces.

Even in the media, the influence of international cooperation-oriented newspapers such as the Asahi Shimbun has been steadily weakening.

When the issue of North Korea's abduction of Japanese citizens was confirmed to be true in 2002, progressive left-wing public opinion was shocked.

The second shock came in 2014 when the Asahi Shimbun, which had been active in raising the issue of Japanese military "comfort women," retracted its initial comfort women report, which unverified Yoshida Seiji's claim that military comfort women were forcibly taken from Jeju Island, calling it an incorrect article.

The overall conservative shift in the media landscape has ultimately contributed significantly to Abe's long-term monopoly.

With the total collapse of the left, the political and ideological base to counter the historical revisionism and rightward shift that began in earnest in the late 1990s disappeared.

March 11 and the Expansion of Neoconservative Power

Since the end of the Cold War in the 1990s, Japan has been mired in an identity crisis.

As the Cold War structure disintegrated, a sense of anxiety gripped the Japanese, as if they had been thrown into the middle of the international community.

As the international political front of the anti-communist alliance disappeared in East Asia, the movement to hold people accountable for the sealed past emerged with the issue of the "Japanese military comfort women," which served as an opportunity to reaffirm the hypocrisy of Japan's "closed pacifism" built without an apology, reflection, or settlement of the past.

The comfort women issue has gone beyond the level of relations between Korea and Japan and has been elevated to a common international agenda as a problem of "wartime sexual violence."

The shock brought about by the past served as an opportunity to unite the conservative right wing in Japan, and Japan's nationalistic nationalism began to grow amid this identity anxiety.

North Korea's admission of Japanese abductions in 2002 transformed Japan from a perpetrator into a victim, and in the process, Abe emerged as a key figure of neoconservatism.

It also spread the desire for a "strong Japan" by causing disputes such as the Senkaku Islands (Diaoyu Islands in Chinese) dispute between China and Japan and the territorial dispute between Korea and Dokdo.

Japan was helpless in the face of 3/11.

In the meantime, Japan's status in the international community collapsed in an instant.

A new vision of a "small and safe country" was presented, and voices criticizing the nuclear mafia and advocating for nuclear phase-out erupted, but ultimately, these voices were defeated in their confrontation with the retrograde growth-oriented policies represented by Abe.

The Democratic Party, which was in power at the time, attempted to pursue a nuclear phase-out policy, but was thwarted by US restraint, and was forced to resign after three years and three months, failing to impress during the disaster recovery process.

"The Birth of Neoconservative Japan" examines the process by which Abe, after returning to power, established a "prime ministerial dictatorship" system and nullified the Peace Constitution, as well as the significance of the declaration made on the 70th anniversary of the end of the war that "Japan will no longer apologize to other countries" from the perspective of Korea-Japan relations.

We examine how the revision of the US-Japan Defense Cooperation Guidelines, known as the 2015 Guidelines, and its subsequent measures, such as the enactment and revision of security legislation, have transformed Japan into a country capable of launching war on its own initiative.

This paper examines the process by which Abe, who sought to transform Japan into a strategic nation, created the geopolitical concept of the "Indo-Pacific," and its significance within the context of strengthening the "US-Japan alliance."

In addition, we examine Japan's recently aggressively pursued strategy to revitalize the semiconductor industry, along with its mandatory security measures, in the context of Korea-Japan relations.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 27, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 304 pages | 153*224*30mm

- ISBN13: 9788994606972

- ISBN10: 8994606971

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)