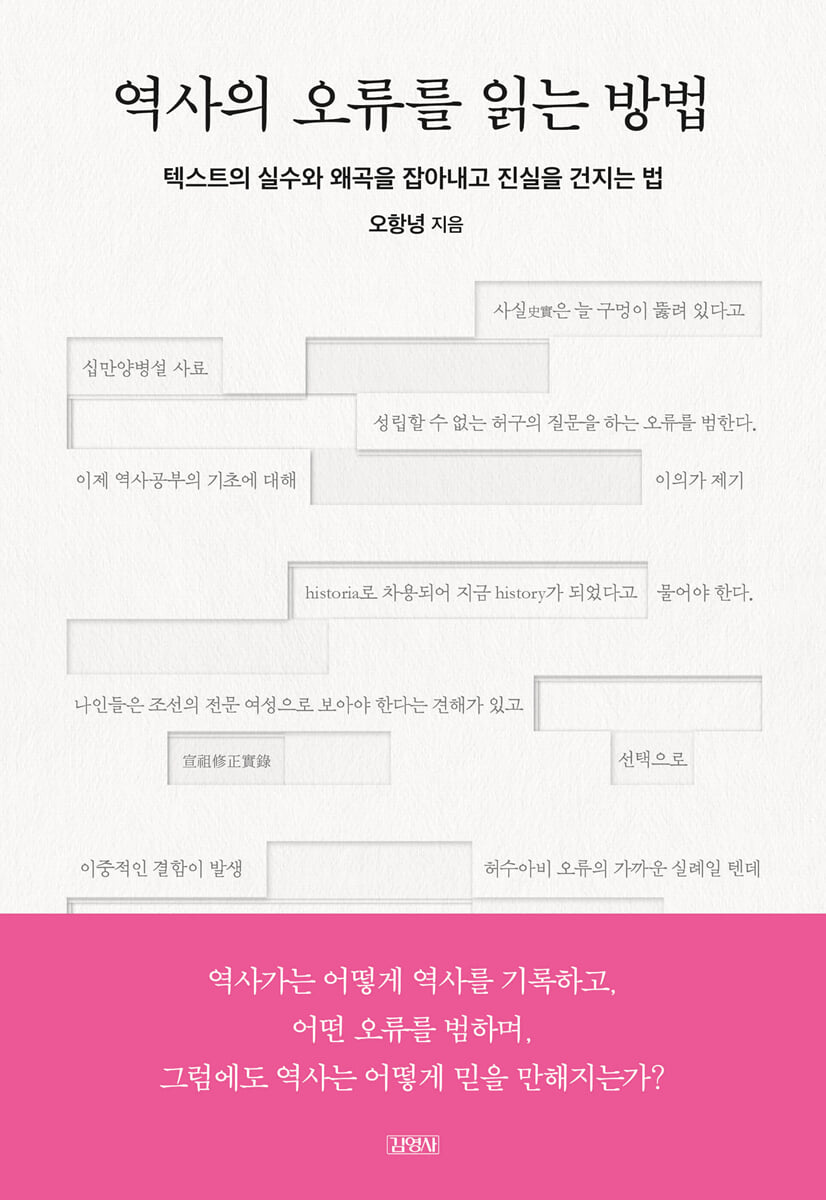

How to Read the Errors of History

|

Description

Book Introduction

Oh Hang-nyeong's Special Lecture on Historical Literacy for Healthy Historical Thinking

From the Hollywood movie “300” to the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty,

From Herodotus's "History" to Yuji's "Historical Works"

How do historians record history, what mistakes do they make,

So how does history become trustworthy?

How is history made, who writes it, and what errors do historians commit? Professor Oh Hang-nyeong, a leading scholar of Joseon history, uses a variety of examples and analogies to illustrate the errors and distortions that can arise in historical records, narratives, and interpretations, drawing on Eastern and Western literature and popular culture.

Historians also make mistakes, sometimes through minor misreadings, sometimes through unconscious bias, and sometimes, in rare cases, through making inappropriate corrections in the name of correcting historical records.

The reason why historical research is difficult is because it is impossible to record a time and situation completely, and the subjects of the record are also 'humans' with imperfect memories.

However, the author suggests that we use these historical gaps and limitations as a starting point for our study of history.

By developing an eye for critically examining texts and rationally reasoning, we aim to overcome the vague distrust and cynicism surrounding historical scholarship.

Thus, readers will realize that our journey, which began with the search for 'historical errors,' is connected to the 'noble journey' of previous historians who struggled to approach the truth.

From the Hollywood movie “300” to the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty,

From Herodotus's "History" to Yuji's "Historical Works"

How do historians record history, what mistakes do they make,

So how does history become trustworthy?

How is history made, who writes it, and what errors do historians commit? Professor Oh Hang-nyeong, a leading scholar of Joseon history, uses a variety of examples and analogies to illustrate the errors and distortions that can arise in historical records, narratives, and interpretations, drawing on Eastern and Western literature and popular culture.

Historians also make mistakes, sometimes through minor misreadings, sometimes through unconscious bias, and sometimes, in rare cases, through making inappropriate corrections in the name of correcting historical records.

The reason why historical research is difficult is because it is impossible to record a time and situation completely, and the subjects of the record are also 'humans' with imperfect memories.

However, the author suggests that we use these historical gaps and limitations as a starting point for our study of history.

By developing an eye for critically examining texts and rationally reasoning, we aim to overcome the vague distrust and cynicism surrounding historical scholarship.

Thus, readers will realize that our journey, which began with the search for 'historical errors,' is connected to the 'noble journey' of previous historians who struggled to approach the truth.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Introduction_ There are no bugs in harmony

Part 1 Even Historians Can Be Wrong: Factual Errors

1 Memento in my body

2 I knew my father's grave

3 Prejudices in the name of civilization

4 300? Sparta?

5. Sleep, Hygiene, and Feudalism

6 The History of Kongjwi and Patjwi

Part 2: How to Convey Reliable Memories—Failures in Narrative

7 The Distance Between Fact and Fiction

8. Encourage healthy skepticism.

9 What is the question of history?

10 Jeonbuk Hyundai FC without coach Choi Kang-hee?

11 Jeongjo did not ascend to the throne in 1776.

12 Streets of History and Commercialism

13 Suspicion is not a mistake, but a disease

14 Criticism of the 19th-century Joseon crisis theory

15 Memories Distorted by the Eiffel Tower

16 Why Did That Happen? - The Boundary of Cause and Effect

17 The Anthropology of Historical Distortion

Part 3: How to Interpret History: Errors in Interpretation

18 Finding the Lee Kwang-soo within us

19. The distortion of the Sado Crown Prince's story

20 I thought they were all the same

21 The Double-Edged Sword of 'Parable'

22 Facts are the basis for interpretation and debate

23 'Oh Hang-nyeong is a far-right fascist!'

24 The Truth of History, Hope for Life

Epilogue_ Study history later?

main

Source of the illustration

Search

Part 1 Even Historians Can Be Wrong: Factual Errors

1 Memento in my body

2 I knew my father's grave

3 Prejudices in the name of civilization

4 300? Sparta?

5. Sleep, Hygiene, and Feudalism

6 The History of Kongjwi and Patjwi

Part 2: How to Convey Reliable Memories—Failures in Narrative

7 The Distance Between Fact and Fiction

8. Encourage healthy skepticism.

9 What is the question of history?

10 Jeonbuk Hyundai FC without coach Choi Kang-hee?

11 Jeongjo did not ascend to the throne in 1776.

12 Streets of History and Commercialism

13 Suspicion is not a mistake, but a disease

14 Criticism of the 19th-century Joseon crisis theory

15 Memories Distorted by the Eiffel Tower

16 Why Did That Happen? - The Boundary of Cause and Effect

17 The Anthropology of Historical Distortion

Part 3: How to Interpret History: Errors in Interpretation

18 Finding the Lee Kwang-soo within us

19. The distortion of the Sado Crown Prince's story

20 I thought they were all the same

21 The Double-Edged Sword of 'Parable'

22 Facts are the basis for interpretation and debate

23 'Oh Hang-nyeong is a far-right fascist!'

24 The Truth of History, Hope for Life

Epilogue_ Study history later?

main

Source of the illustration

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

If our food is unclean and lacks nutrition, our bodies cannot be healthy.

Likewise, if history is not healthy, neither history nor any other discipline can be healthy.

This book is a small effort toward a healthy exploration of history.

--- p.6~7

What traces are complete, what transmissions are accurate, what stories are reproductions of the past itself? History, which deals with past events in space and time, possesses such an inherent aporia.

However, like the word aporia, which means both a dead end and a beginning, history is an academic discipline that approaches the truth by gradually removing its limitations and distortions.

--- p.16

If the view that "all history is the history of the victors" is correct, where does all the attention we pay to the losers of history come from? Isn't even the view that "all history is the history of the victors" a possible perspective because "all history is not the history of the victors"? Yes, it is.

Even if victory or defeat is determined and recorded, history is not written only through the eyes of the victor.

--- p.24

There is a saying that the word 'bin' means to set up a funeral hall, but at the time, it meant a shallow, temporary grave.

You can understand it as a temporary grave.

Meanwhile, a deep burial (deep burial) refers to a grave that is buried forever without being moved.

So, it was not that Confucius did not know where his father's tomb was, but rather that he did not know whether his father's tomb at the intersection of the five-bu was in the ceiling or in the heart, that is, whether it was a temporary tomb or a permanent tomb.

--- p.53

Medieval physical forms were brutal, but not barbaric.

It is a civilized act with meticulous calculation of reasons, procedures and processes, punishment, and effects.

Therefore, calling medieval physical punishments barbaric is a ploy by the 'civilized world' to define as 'barbaric' a world where punishments of a different dimension still exist, as in the case of 'Chinese cruelty'.

Would it be justifiable to say that ‘civilization’ replaces ‘civilization’?

--- p.66

Everyone makes mistakes in the process of exploring history.

Therefore, historians should not strive to become people who do not make mistakes, but rather to reduce their errors.

One of the good ways is doubt.

I doubt myself and I doubt the data.

Even research papers and books that have already been submitted are viewed with suspicion.

--- p.147

A close example of the straw man fallacy is when the term Silhak is used to contrast the real and the false, thereby defining Neo-Confucianism as a "false study." If the selfish desire to elevate one's family learning is added to this, one's own ancestors are portrayed as good people, while scholars who are not like that are portrayed as bad or flawed.

--- p.159

Fisher refused to answer the question 'why'.

That's an inaccurate question.

Because the word 'why' can be a cause, a motive, a reason, a description, a process, a purpose, or a justification.

'Why' lacks direction and clarity, which diverts the historian's energy and attention.

So who, when, where, what, and how are important.

Because you can get a much more specific and satisfactory answer.

--- p.174~175

Questions like “Would Hyundai have won the championship without Lee Dong-gook?” cannot be considered historical questions.

Why? Because it's a hypothesis that never happened.

The phenomenon that could have occurred 'if' Lee Dong-guk was, ironically, extracted from the 'conditions in which Lee Dong-guk actually played' on the field.

--- p.182

Whether capitalism or socialism is seen as the end of history, or in other words, whether one views modernity as the end of history, during the era when historicism, which considered modernization to be an absolute good, was prevalent, Silhak (practical learning) hovered over Joseon history like a ghost.

So, the study of Joseon history was not really a study of Joseon history.

It was merely a secondary history that intermittently provided material for explaining modernization, that is, for writing modern history.

--- p.272

Although the defeat of the Invincible Armada was a very powerful historical event, its consequences may not have been significant.

In reality, the defeat of the Invincible Armada had little impact thereafter.

Because we believe that major events inevitably have serious consequences.

But that's not always the case.

In the view of causality surrounding the defeat of the Invincible Armada and its consequences, we find the 'error that followed'.

Because it happened first, it is pointed out as the cause of the incident.

--- p.286

The most serious error in evaluating reality by being obsessed with justification is the error of mistaking responsibility for the cause.

I repeat, whether it is Seonjo or Injo, the rulers must take responsibility for the war.

That's why he's a politician.

But these people or their policies are not the cause of the war.

One of the main causes was the invasion of the Japanese army and the Later Jin (Qing) dynasty.

If we confuse these points, we fall into a swamp of causes.

--- p.295~296

As previously mentioned, the reason why Crown Prince Sado died in the back room was distorted by his son, Jeongjo, who tried to cover up his father's madness and misconduct.

However, the reproduction of the distortion of Jeongjo is largely due to the academic world's insufficient review of historical materials.

Moreover, because of the tragic nature of the situation, rather than approaching the facts to determine the cause, they cater to the public's sensationalism by finding some plausible reason and preferring tragedy.

There was also a tendency to do so.

--- p.345

Modern enlightenment thinkers likened their era to 'light' and the feudal era to 'darkness'.

'Enlightenment' is a translation of 'Enlightenment (English), Aufklarung (German),' and is a translation that appropriately expresses the metaphor of the Dark Age and the Age of Light.

Because it is ‘awakening [啓] foolishness [蒙].’

Through this metaphor, the Middle Ages and feudalism came to mean darkness, barbarism, and stagnation, while the modern era was described as an era of reason, civilization, freedom, and liberation.

The moment we use this metaphor, the contrast between light and darkness becomes stark, and we unknowingly fall into the 'fallacy of clichéd, unconscious metaphor'.

--- p.367

The reason historical sources are important is because they serve to prevent perspectives or interpretations from drifting into delusion.

This is also the most important value among the virtues of history.

You need to look at a lot of historical data.

That way you don't make mistakes.

Some people are not interested in feed.

I'm only interested in 'perspectives'.

History shouldn't be like this.

--- p.388

Historians, too, when trying to be more persuasive, use expressions such as "always" instead of "sometimes," "occasionally" instead of "occasionally," "sometimes" instead of "rarely," and "rarely" instead of "once."

So there's a joke that when a historian says "certainly," you should understand it as "probably," when he says "probably," you should understand it as "maybe," and when he says "maybe," you should understand it as "presumably."

--- p.390

Errors discovered in inquiry or argument are not outward manifestations of the author's vices.

Even competent historians make mistakes.

No, the more competent a historian is, the more likely he is to make mistakes because he reads and writes extensively.

It is not the task of history to investigate whether he intended to deceive the reader.

If you lied, write that you lied. If it seems like you lied, write that you seemed to have lied. If there is no such circumstance, just point out the error, and that's it.

Likewise, if history is not healthy, neither history nor any other discipline can be healthy.

This book is a small effort toward a healthy exploration of history.

--- p.6~7

What traces are complete, what transmissions are accurate, what stories are reproductions of the past itself? History, which deals with past events in space and time, possesses such an inherent aporia.

However, like the word aporia, which means both a dead end and a beginning, history is an academic discipline that approaches the truth by gradually removing its limitations and distortions.

--- p.16

If the view that "all history is the history of the victors" is correct, where does all the attention we pay to the losers of history come from? Isn't even the view that "all history is the history of the victors" a possible perspective because "all history is not the history of the victors"? Yes, it is.

Even if victory or defeat is determined and recorded, history is not written only through the eyes of the victor.

--- p.24

There is a saying that the word 'bin' means to set up a funeral hall, but at the time, it meant a shallow, temporary grave.

You can understand it as a temporary grave.

Meanwhile, a deep burial (deep burial) refers to a grave that is buried forever without being moved.

So, it was not that Confucius did not know where his father's tomb was, but rather that he did not know whether his father's tomb at the intersection of the five-bu was in the ceiling or in the heart, that is, whether it was a temporary tomb or a permanent tomb.

--- p.53

Medieval physical forms were brutal, but not barbaric.

It is a civilized act with meticulous calculation of reasons, procedures and processes, punishment, and effects.

Therefore, calling medieval physical punishments barbaric is a ploy by the 'civilized world' to define as 'barbaric' a world where punishments of a different dimension still exist, as in the case of 'Chinese cruelty'.

Would it be justifiable to say that ‘civilization’ replaces ‘civilization’?

--- p.66

Everyone makes mistakes in the process of exploring history.

Therefore, historians should not strive to become people who do not make mistakes, but rather to reduce their errors.

One of the good ways is doubt.

I doubt myself and I doubt the data.

Even research papers and books that have already been submitted are viewed with suspicion.

--- p.147

A close example of the straw man fallacy is when the term Silhak is used to contrast the real and the false, thereby defining Neo-Confucianism as a "false study." If the selfish desire to elevate one's family learning is added to this, one's own ancestors are portrayed as good people, while scholars who are not like that are portrayed as bad or flawed.

--- p.159

Fisher refused to answer the question 'why'.

That's an inaccurate question.

Because the word 'why' can be a cause, a motive, a reason, a description, a process, a purpose, or a justification.

'Why' lacks direction and clarity, which diverts the historian's energy and attention.

So who, when, where, what, and how are important.

Because you can get a much more specific and satisfactory answer.

--- p.174~175

Questions like “Would Hyundai have won the championship without Lee Dong-gook?” cannot be considered historical questions.

Why? Because it's a hypothesis that never happened.

The phenomenon that could have occurred 'if' Lee Dong-guk was, ironically, extracted from the 'conditions in which Lee Dong-guk actually played' on the field.

--- p.182

Whether capitalism or socialism is seen as the end of history, or in other words, whether one views modernity as the end of history, during the era when historicism, which considered modernization to be an absolute good, was prevalent, Silhak (practical learning) hovered over Joseon history like a ghost.

So, the study of Joseon history was not really a study of Joseon history.

It was merely a secondary history that intermittently provided material for explaining modernization, that is, for writing modern history.

--- p.272

Although the defeat of the Invincible Armada was a very powerful historical event, its consequences may not have been significant.

In reality, the defeat of the Invincible Armada had little impact thereafter.

Because we believe that major events inevitably have serious consequences.

But that's not always the case.

In the view of causality surrounding the defeat of the Invincible Armada and its consequences, we find the 'error that followed'.

Because it happened first, it is pointed out as the cause of the incident.

--- p.286

The most serious error in evaluating reality by being obsessed with justification is the error of mistaking responsibility for the cause.

I repeat, whether it is Seonjo or Injo, the rulers must take responsibility for the war.

That's why he's a politician.

But these people or their policies are not the cause of the war.

One of the main causes was the invasion of the Japanese army and the Later Jin (Qing) dynasty.

If we confuse these points, we fall into a swamp of causes.

--- p.295~296

As previously mentioned, the reason why Crown Prince Sado died in the back room was distorted by his son, Jeongjo, who tried to cover up his father's madness and misconduct.

However, the reproduction of the distortion of Jeongjo is largely due to the academic world's insufficient review of historical materials.

Moreover, because of the tragic nature of the situation, rather than approaching the facts to determine the cause, they cater to the public's sensationalism by finding some plausible reason and preferring tragedy.

There was also a tendency to do so.

--- p.345

Modern enlightenment thinkers likened their era to 'light' and the feudal era to 'darkness'.

'Enlightenment' is a translation of 'Enlightenment (English), Aufklarung (German),' and is a translation that appropriately expresses the metaphor of the Dark Age and the Age of Light.

Because it is ‘awakening [啓] foolishness [蒙].’

Through this metaphor, the Middle Ages and feudalism came to mean darkness, barbarism, and stagnation, while the modern era was described as an era of reason, civilization, freedom, and liberation.

The moment we use this metaphor, the contrast between light and darkness becomes stark, and we unknowingly fall into the 'fallacy of clichéd, unconscious metaphor'.

--- p.367

The reason historical sources are important is because they serve to prevent perspectives or interpretations from drifting into delusion.

This is also the most important value among the virtues of history.

You need to look at a lot of historical data.

That way you don't make mistakes.

Some people are not interested in feed.

I'm only interested in 'perspectives'.

History shouldn't be like this.

--- p.388

Historians, too, when trying to be more persuasive, use expressions such as "always" instead of "sometimes," "occasionally" instead of "occasionally," "sometimes" instead of "rarely," and "rarely" instead of "once."

So there's a joke that when a historian says "certainly," you should understand it as "probably," when he says "probably," you should understand it as "maybe," and when he says "maybe," you should understand it as "presumably."

--- p.390

Errors discovered in inquiry or argument are not outward manifestations of the author's vices.

Even competent historians make mistakes.

No, the more competent a historian is, the more likely he is to make mistakes because he reads and writes extensively.

It is not the task of history to investigate whether he intended to deceive the reader.

If you lied, write that you lied. If it seems like you lied, write that you seemed to have lied. If there is no such circumstance, just point out the error, and that's it.

--- p.418~419

Publisher's Review

How do historians record history, what mistakes do they make,

So how does history become trustworthy?

From the Hollywood movie [300] to the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty,

From Herodotus's "History" to Yuji's "Shi Tong"

Professor Oh Hang-nyeong's special lecture on historical literacy for healthy historical thinking

Even historians get it wrong

Historians also make mistakes, sometimes through minor misreadings, sometimes through unconscious bias, and sometimes, in rare cases, through making inappropriate corrections in the name of correcting historical records.

How is history made, who writes it, and what errors do historians commit? "How to Read the Errors of History" is a history textbook written by Professor Oh Hang-nyeong, a leading Korean scholar of Joseon history, who humorously explains the mistakes made by historians throughout history.

Errors and mistakes that appear in each process of historical recording, description, and interpretation are organized by theme along with the main concepts of history.

These are interesting cases collected through research, debate, and teaching over a long period of time through lectures and writing.

The literature referenced and cited by the author is also extensive.

The works of Herodotus and Sima Qian, two giants representing Eastern and Western history (『History』, 『Records of the Grand Historian』) cannot be left out, and important historical documents are included in significant quantities, from 『Sitong (史通)』, the first introductory book on history in human history, to [Joseon Dynasty Annals], which represents our recorded culture.

He explains the subject at a level suitable for general readers, using appropriate metaphors from popular culture, such as the movie [300] and the musical [Les Miserables], sports, and even citing test questions given to students during class and his own diary.

In particular, it actively brings up controversial issues in Korean historiography as examples of historical errors and criticizes them. It covers a wide range of important issues in Korean history, including the historical records of the Annals of King Seonjo and the Annals of King Seonjo, biographical assessments of King Gwanghaegun and Crown Prince Sado, the Silhak/Heohak debate, and the controversy surrounding Yulgok Yi I's theory of raising 100,000 troops.

Ordinary people who find history vaguely difficult and burdensome will be able to experience the deep pleasure of reading history, and historians who wish to pursue history as a career will be able to obtain useful tips on what to watch out for when reading, interpreting, and critiquing historical materials.

How to Read the Errors of History

The title of the book is a bit unusual.

Some readers may be indifferent, thinking, “I don’t even know much about history… do I really need to know all the details about the errors in history?” since it’s not about “how to read history.”

The author likens history to 'food' that keeps all other disciplines healthy.

If we eat nutritious and healthy food, our body (and intellectual foundation) will be strong, but if we eat food that is poor in nutrients and spoiled, all other academic fields will be in jeopardy.

Because history is “the form and nature of all disciplines (including the history of science, the history of philosophy, and even the history of history).”

Reducing and preventing 'historical errors' is as essential as preserving the foundation of our scholarship.

Moreover, in any field, failures serve as guides to the secrets of success, and it is difficult to find a more useful textbook for studying history than the stories of historians' mistakes.

The theme of 'historical errors' is also a methodology adopted by the author while contemplating how to explain history more easily.

This book presents various examples of historical errors.

In the case of Confucius, later scholars misread the 『Book of Rites』, which recorded his childhood, by placing punctuation marks in the wrong places, so for a long time Confucius was known as someone who did not even know his father's grave, and China's 5,000-year civilization was reduced to a synonym for barbarism because of a single photo (the execution of Wang Weiqin) taken by a British person who had a prejudice against the East.

Some high school Korean history textbooks even included a section from Yeonam Park Ji-won's 『Yeolha Diary』, using a subtitle that was diametrically opposed to Park Ji-won's own views on China.

Of course, the author of this book is no exception to this error, and he honestly confesses that he suffered a setback because he misinterpreted the words of Hu Sancheng of the Yuan Dynasty, a researcher of the Zizhi Tongjian.

Likewise, historians' theses and writings, middle and high school textbooks, guidebooks for Joseon Dynasty royal tombs, and even the respected Confucian masters of East Asia can all be wrong.

Because the subjects who record, convey, and interpret history are people.

Examples of typical errors

This book is divided into three parts.

Part 1, 'Factual Errors', deals with errors that occur when leaving records and errors that occur when approaching facts with some preconceived notion or bias.

It explains errors that arise, especially from ignorance or misunderstanding of letters and language.

Part 2, “Failures in Narration,” deals with errors that occur in the process of writing, conveying, and telling facts.

For example, hypothetical questions that we ask ourselves without much thought in our daily lives, such as, "Would Joseon have fallen without Admiral Yi Sun-sin?" are also examined here.

Explains why such questions should not be brought into the study of history.

Part 3, “Errors in Criticism,” deals with errors that can be found in debates surrounding history.

These include errors such as confusing the topic and the person, such as saying, "I can't believe what you're saying!", and errors such as inducing a fight to hide one's own errors.

An interesting example is the warning to be careful of the common hyperbole of historians: “Even historians, when trying to be persuasive, use expressions such as ‘always’ instead of ‘sometimes,’ ‘occasionally’ instead of ‘sometimes,’ and ‘rarely’ instead of ‘seldom.’

So there's a joke that when a historian says 'certainly,' you should understand it as 'probably,' when he says 'probably,' you should understand it as 'perhaps,' and when he says 'perhaps,' you should understand it as 'presumably.'" Here are just a few representative concepts among the examples of errors included in this book.

· The fallacy of fictitious questions

It refers to asking hypothetical questions based on assumptions that have not occurred.

American economic historian Robert W.

In "Railroads and Economic Growth," Fogel concluded that highways and canals were sufficient for the development of the 19th-century American economy, and that railroads were unnecessary.

This is a conclusion based on analysis of various statistical data, but in fact, the statistics were taken from a world where railways already exist.

A simple example is the familiar question, “If it weren’t for Admiral Yi Sun-sin, would we have lost the Imjin War?”

Any citizen of the Republic of Korea who admires Admiral Yi Sun-sin would be confident that without him, we would have lost to the Japanese army. However, the basis for such a judgment is actually derived from the circumstances of the time when Yi Sun-sin was active.

We have absolutely no data on who would replace Admiral Yi Sun-sin or what new variables might emerge.

So, the reason why history cannot answer such hypothetical questions is because there is no historical material to explain them.

History begins with reading 'source materials'.

· The straw man fallacy

Readers of history should be wary of historians who attribute events to specific enemies without clear evidence.

It is a kind of putting up a scarecrow. “During the Song Dynasty, when the treacherous official Han Tak-ju tried to frame the famous general and loyal official Yue Fei, he put forward the logic of ‘no need to have.’

“It is said that ‘there is nothing that has been revealed, but it is certain.’” It is similar to cases in which ‘enemies’ were created through assumptions and speculations during the past military regimes.

The author adds that defining Neo-Confucianism as “empty learning” by contrasting “real” and “empty” by using the term “silhak” is also an example of the fallacy of straw man.

· Anachronistic error

This refers to a historian describing, analyzing, and judging an event as if it had occurred in a time other than the one it actually occurred in.

For example, it is to interpret the agriculture of Goryeo and Joseon, which used hoes and plows, from the perspective of the current rural area that uses tractors.

On the other hand, there are cases where civilizations with different time units are interpreted based on one standard.

The Western calendar, also known as the Gregorian calendar, is the calendar used in Joseon after the Gabo Reform.

Before that, there was no such distinction of years, and the standard was the year of Gapja (60 years) or the king's reign.

Recently, local governments have been commemorating the births of Joseon Dynasty figures such as Yulgok Yi I and Dasan Jeong Yak-yong in 100-year and 50-year increments, but this is only our current standard.

During the Joseon Dynasty, 3-gapja and 4-gapja would have been more memorable time units.

· The fallacy of 'as you all know'

It is an error that involves drawing on the opinions of the majority and using them as a basis, and is accompanied by intellectual laziness on the part of the researcher.

According to the author, “At one time, it was fashionable in Joseon Dynasty theses to begin the introduction with ‘In the late Joseon Dynasty, the commodity money economy developed and the class system was shaken…’”

Even in the late Joseon Dynasty, it was only 300 years, but that 300 years was summarized in one word, as if 'we all knew it'.

According to the author, while actual Joseon society was not friendly to the 'commodity money economy' and changes in the class system were taking place, there was scant evidence to support calling it a '300-year period of unrest.'

To avoid such errors, we must cultivate the integrity and courage to reexamine the claims of existing researchers based on our own research, rather than blindly following their arguments.

· The error of confusing responsibility with cause

This refers to cases where the issue of ethical responsibility is confused with the issue of the performer.

For example, if a war breaks out, the rulers cannot avoid responsibility, regardless of the cause.

In the case of the Byeongja Horan and the Jeongmyo Horan, King Injo, who was the ruler at the time, took infinite responsibility for the war.

However, this does not mean that the king or his policies were the direct cause of the war.

The main cause was the invasion of the Japanese army and the Later Jin (Qing) dynasty.

The question “How did it happen?” is one thing, and the question “Who is to blame?” is another.

It's difficult to confuse the two.

· The fallacy of appealing to authority

It's a familiar fallacy, one that historians often use to discourage readers and cover up their weak arguments.

Arguments that begin with, ‘The scientist who won such-and-such award said,’ or ‘Confucius (Buddha, Jesus) said,’ fall into this category.

Variants include:

Excessive bibliography, descriptions centered on numerous quotations, a staggeringly large volume (Arnold Toynbee's 『A Study of History』 was published in 14 volumes in Korea in 1974, and many readers might not have been persuaded by the monumental length of the work?), and the overuse of mathematical formulas that completely silence the reader.

For a rich and healthy study of history

The reason why historical research is difficult is because it is impossible to record a time and situation completely, and the subjects of the records are also 'humans' with imperfect memories.

However, the author suggests that we use these historical gaps and limitations as a starting point for our study of history.

By developing an eye for critically examining texts and rationally reasoning, we aim to overcome the vague distrust and cynicism surrounding historical scholarship.

Readers who have reached the final chapter of this book will realize that our journey, which began with the search for "historical errors," is connected to the "noble spirits" of previous historians who struggled to approach the truth.

The true power of history comes from its ability to correct itself.

Because even leaving errors on record is history and the historian's job.

“If there was a lie, write that there was a lie. If there seems to be a lie, write that there seems to be a lie. If there is no such circumstance, just point out the error, and that’s it.” However, it is not right for the historian’s creative thinking to be stifled by an excessive obsession with error.

Reducing errors is not the goal of history; it is merely a means to a rich and healthy history.

“A reason without errors is not the only healthy reason.

Reasoning that consists only of propositions is antique.

How much does the thought of questioning, doubting, and creating enrich our lives?

“It would be foolish to give up the possibility of abundance in order to avoid error.” This exhortation from the author is worth pondering for both those who teach history and those who study it.

So how does history become trustworthy?

From the Hollywood movie [300] to the Annals of the Joseon Dynasty,

From Herodotus's "History" to Yuji's "Shi Tong"

Professor Oh Hang-nyeong's special lecture on historical literacy for healthy historical thinking

Even historians get it wrong

Historians also make mistakes, sometimes through minor misreadings, sometimes through unconscious bias, and sometimes, in rare cases, through making inappropriate corrections in the name of correcting historical records.

How is history made, who writes it, and what errors do historians commit? "How to Read the Errors of History" is a history textbook written by Professor Oh Hang-nyeong, a leading Korean scholar of Joseon history, who humorously explains the mistakes made by historians throughout history.

Errors and mistakes that appear in each process of historical recording, description, and interpretation are organized by theme along with the main concepts of history.

These are interesting cases collected through research, debate, and teaching over a long period of time through lectures and writing.

The literature referenced and cited by the author is also extensive.

The works of Herodotus and Sima Qian, two giants representing Eastern and Western history (『History』, 『Records of the Grand Historian』) cannot be left out, and important historical documents are included in significant quantities, from 『Sitong (史通)』, the first introductory book on history in human history, to [Joseon Dynasty Annals], which represents our recorded culture.

He explains the subject at a level suitable for general readers, using appropriate metaphors from popular culture, such as the movie [300] and the musical [Les Miserables], sports, and even citing test questions given to students during class and his own diary.

In particular, it actively brings up controversial issues in Korean historiography as examples of historical errors and criticizes them. It covers a wide range of important issues in Korean history, including the historical records of the Annals of King Seonjo and the Annals of King Seonjo, biographical assessments of King Gwanghaegun and Crown Prince Sado, the Silhak/Heohak debate, and the controversy surrounding Yulgok Yi I's theory of raising 100,000 troops.

Ordinary people who find history vaguely difficult and burdensome will be able to experience the deep pleasure of reading history, and historians who wish to pursue history as a career will be able to obtain useful tips on what to watch out for when reading, interpreting, and critiquing historical materials.

How to Read the Errors of History

The title of the book is a bit unusual.

Some readers may be indifferent, thinking, “I don’t even know much about history… do I really need to know all the details about the errors in history?” since it’s not about “how to read history.”

The author likens history to 'food' that keeps all other disciplines healthy.

If we eat nutritious and healthy food, our body (and intellectual foundation) will be strong, but if we eat food that is poor in nutrients and spoiled, all other academic fields will be in jeopardy.

Because history is “the form and nature of all disciplines (including the history of science, the history of philosophy, and even the history of history).”

Reducing and preventing 'historical errors' is as essential as preserving the foundation of our scholarship.

Moreover, in any field, failures serve as guides to the secrets of success, and it is difficult to find a more useful textbook for studying history than the stories of historians' mistakes.

The theme of 'historical errors' is also a methodology adopted by the author while contemplating how to explain history more easily.

This book presents various examples of historical errors.

In the case of Confucius, later scholars misread the 『Book of Rites』, which recorded his childhood, by placing punctuation marks in the wrong places, so for a long time Confucius was known as someone who did not even know his father's grave, and China's 5,000-year civilization was reduced to a synonym for barbarism because of a single photo (the execution of Wang Weiqin) taken by a British person who had a prejudice against the East.

Some high school Korean history textbooks even included a section from Yeonam Park Ji-won's 『Yeolha Diary』, using a subtitle that was diametrically opposed to Park Ji-won's own views on China.

Of course, the author of this book is no exception to this error, and he honestly confesses that he suffered a setback because he misinterpreted the words of Hu Sancheng of the Yuan Dynasty, a researcher of the Zizhi Tongjian.

Likewise, historians' theses and writings, middle and high school textbooks, guidebooks for Joseon Dynasty royal tombs, and even the respected Confucian masters of East Asia can all be wrong.

Because the subjects who record, convey, and interpret history are people.

Examples of typical errors

This book is divided into three parts.

Part 1, 'Factual Errors', deals with errors that occur when leaving records and errors that occur when approaching facts with some preconceived notion or bias.

It explains errors that arise, especially from ignorance or misunderstanding of letters and language.

Part 2, “Failures in Narration,” deals with errors that occur in the process of writing, conveying, and telling facts.

For example, hypothetical questions that we ask ourselves without much thought in our daily lives, such as, "Would Joseon have fallen without Admiral Yi Sun-sin?" are also examined here.

Explains why such questions should not be brought into the study of history.

Part 3, “Errors in Criticism,” deals with errors that can be found in debates surrounding history.

These include errors such as confusing the topic and the person, such as saying, "I can't believe what you're saying!", and errors such as inducing a fight to hide one's own errors.

An interesting example is the warning to be careful of the common hyperbole of historians: “Even historians, when trying to be persuasive, use expressions such as ‘always’ instead of ‘sometimes,’ ‘occasionally’ instead of ‘sometimes,’ and ‘rarely’ instead of ‘seldom.’

So there's a joke that when a historian says 'certainly,' you should understand it as 'probably,' when he says 'probably,' you should understand it as 'perhaps,' and when he says 'perhaps,' you should understand it as 'presumably.'" Here are just a few representative concepts among the examples of errors included in this book.

· The fallacy of fictitious questions

It refers to asking hypothetical questions based on assumptions that have not occurred.

American economic historian Robert W.

In "Railroads and Economic Growth," Fogel concluded that highways and canals were sufficient for the development of the 19th-century American economy, and that railroads were unnecessary.

This is a conclusion based on analysis of various statistical data, but in fact, the statistics were taken from a world where railways already exist.

A simple example is the familiar question, “If it weren’t for Admiral Yi Sun-sin, would we have lost the Imjin War?”

Any citizen of the Republic of Korea who admires Admiral Yi Sun-sin would be confident that without him, we would have lost to the Japanese army. However, the basis for such a judgment is actually derived from the circumstances of the time when Yi Sun-sin was active.

We have absolutely no data on who would replace Admiral Yi Sun-sin or what new variables might emerge.

So, the reason why history cannot answer such hypothetical questions is because there is no historical material to explain them.

History begins with reading 'source materials'.

· The straw man fallacy

Readers of history should be wary of historians who attribute events to specific enemies without clear evidence.

It is a kind of putting up a scarecrow. “During the Song Dynasty, when the treacherous official Han Tak-ju tried to frame the famous general and loyal official Yue Fei, he put forward the logic of ‘no need to have.’

“It is said that ‘there is nothing that has been revealed, but it is certain.’” It is similar to cases in which ‘enemies’ were created through assumptions and speculations during the past military regimes.

The author adds that defining Neo-Confucianism as “empty learning” by contrasting “real” and “empty” by using the term “silhak” is also an example of the fallacy of straw man.

· Anachronistic error

This refers to a historian describing, analyzing, and judging an event as if it had occurred in a time other than the one it actually occurred in.

For example, it is to interpret the agriculture of Goryeo and Joseon, which used hoes and plows, from the perspective of the current rural area that uses tractors.

On the other hand, there are cases where civilizations with different time units are interpreted based on one standard.

The Western calendar, also known as the Gregorian calendar, is the calendar used in Joseon after the Gabo Reform.

Before that, there was no such distinction of years, and the standard was the year of Gapja (60 years) or the king's reign.

Recently, local governments have been commemorating the births of Joseon Dynasty figures such as Yulgok Yi I and Dasan Jeong Yak-yong in 100-year and 50-year increments, but this is only our current standard.

During the Joseon Dynasty, 3-gapja and 4-gapja would have been more memorable time units.

· The fallacy of 'as you all know'

It is an error that involves drawing on the opinions of the majority and using them as a basis, and is accompanied by intellectual laziness on the part of the researcher.

According to the author, “At one time, it was fashionable in Joseon Dynasty theses to begin the introduction with ‘In the late Joseon Dynasty, the commodity money economy developed and the class system was shaken…’”

Even in the late Joseon Dynasty, it was only 300 years, but that 300 years was summarized in one word, as if 'we all knew it'.

According to the author, while actual Joseon society was not friendly to the 'commodity money economy' and changes in the class system were taking place, there was scant evidence to support calling it a '300-year period of unrest.'

To avoid such errors, we must cultivate the integrity and courage to reexamine the claims of existing researchers based on our own research, rather than blindly following their arguments.

· The error of confusing responsibility with cause

This refers to cases where the issue of ethical responsibility is confused with the issue of the performer.

For example, if a war breaks out, the rulers cannot avoid responsibility, regardless of the cause.

In the case of the Byeongja Horan and the Jeongmyo Horan, King Injo, who was the ruler at the time, took infinite responsibility for the war.

However, this does not mean that the king or his policies were the direct cause of the war.

The main cause was the invasion of the Japanese army and the Later Jin (Qing) dynasty.

The question “How did it happen?” is one thing, and the question “Who is to blame?” is another.

It's difficult to confuse the two.

· The fallacy of appealing to authority

It's a familiar fallacy, one that historians often use to discourage readers and cover up their weak arguments.

Arguments that begin with, ‘The scientist who won such-and-such award said,’ or ‘Confucius (Buddha, Jesus) said,’ fall into this category.

Variants include:

Excessive bibliography, descriptions centered on numerous quotations, a staggeringly large volume (Arnold Toynbee's 『A Study of History』 was published in 14 volumes in Korea in 1974, and many readers might not have been persuaded by the monumental length of the work?), and the overuse of mathematical formulas that completely silence the reader.

For a rich and healthy study of history

The reason why historical research is difficult is because it is impossible to record a time and situation completely, and the subjects of the records are also 'humans' with imperfect memories.

However, the author suggests that we use these historical gaps and limitations as a starting point for our study of history.

By developing an eye for critically examining texts and rationally reasoning, we aim to overcome the vague distrust and cynicism surrounding historical scholarship.

Readers who have reached the final chapter of this book will realize that our journey, which began with the search for "historical errors," is connected to the "noble spirits" of previous historians who struggled to approach the truth.

The true power of history comes from its ability to correct itself.

Because even leaving errors on record is history and the historian's job.

“If there was a lie, write that there was a lie. If there seems to be a lie, write that there seems to be a lie. If there is no such circumstance, just point out the error, and that’s it.” However, it is not right for the historian’s creative thinking to be stifled by an excessive obsession with error.

Reducing errors is not the goal of history; it is merely a means to a rich and healthy history.

“A reason without errors is not the only healthy reason.

Reasoning that consists only of propositions is antique.

How much does the thought of questioning, doubting, and creating enrich our lives?

“It would be foolish to give up the possibility of abundance in order to avoid error.” This exhortation from the author is worth pondering for both those who teach history and those who study it.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: July 19, 2024

- Page count, weight, size: 452 pages | 672g | 148*215*25mm

- ISBN13: 9788934935575

- ISBN10: 893493557X

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)