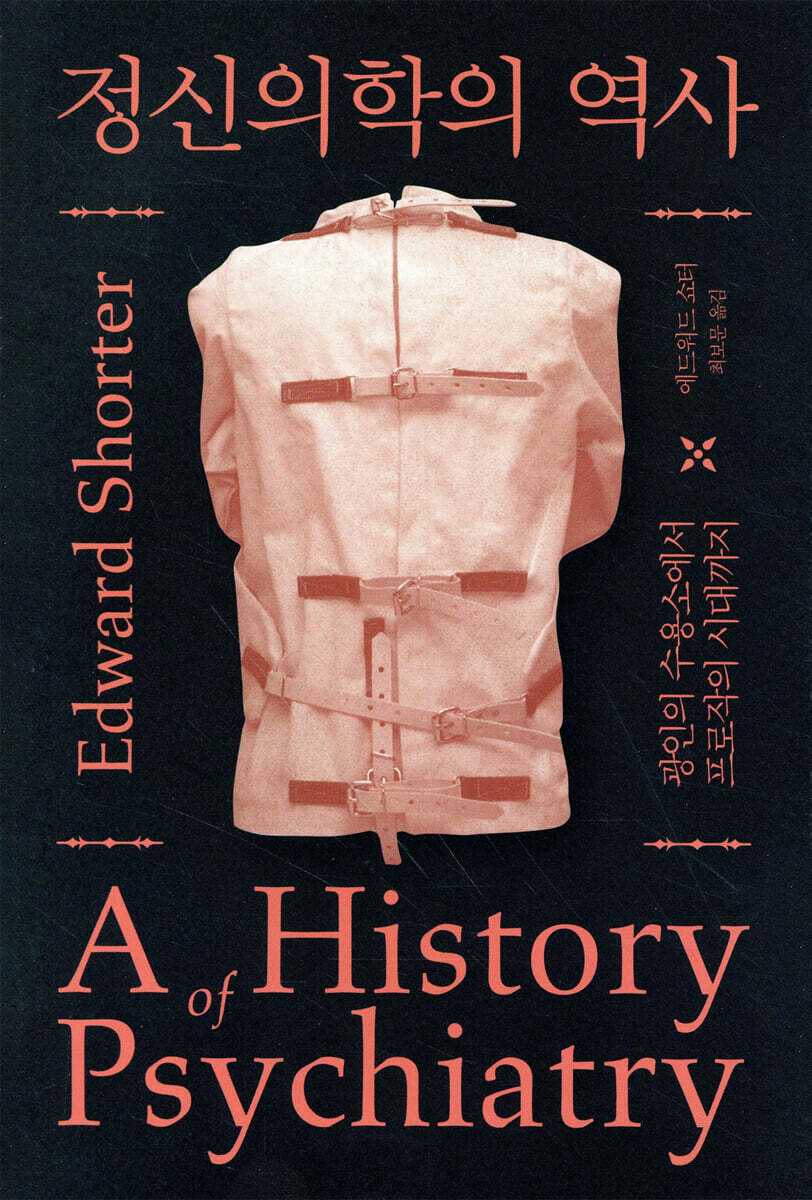

History of Psychiatry

|

Description

Book Introduction

Writing the history of psychiatry

Records that run the gap between science and society Before the modern era, madmen were “handled” by each household or village, and psychiatry, which emerged only after the 17th century, took its first steps while being stigmatized as “mass confinement.”

Doctors performed sloppy brain surgeries, patients had their skulls amputated for no apparent reason, and victims of unfounded treatments like cold and hot water friction and electric shock. Fifty years later, modern psychiatrists are trying to lump all personality traits and existential suffering under the umbrella of illness, and big pharmaceutical companies have made psychiatric drugs like Prozac into household remedies.

The history this book tells is linear.

The story begins with the emergence of a psychiatric hospital in the late 18th century and ends in the quiet examination room of a psychiatrist in the late 20th century.

Freudian theory, which has dominated psychiatry for the past half-century, is disappearing like the last snow of winter.

It is time to take a fresh look at the history of psychiatry.

The trend of viewing mental illness as originating in the brain has reached a biological perspective in our time that places top priority on the brain.

Moreover, the history this book writes about is not a history of intellect, but a social history that vividly restores forgotten figures.

We will focus on how psychiatry has influenced and interacted with culture.

It will show how culture and commerce have infiltrated events often portrayed as triumphs of pure science.

The original version of this book, A History of Psychiatry, was published in 1997, and the Korean translation was published in 2009.

And in 2020, a revised edition of the translation will be published.

There is an interval of about 10 years.

If we consider psychiatry in 2009 as quantitatively expanding and broadening its scope from 1997, how will psychiatry in 2020 differ from a decade ago? For over 200 years, psychiatry has pursued the ultimate goal of finding the scientific reality of mental illness, free from the influence of social values and policies.

Does medicine have a responsibility to address the miseries of life beyond illness? At what point does "need" become "want"? (See Translator's Note, p. 545)

Records that run the gap between science and society Before the modern era, madmen were “handled” by each household or village, and psychiatry, which emerged only after the 17th century, took its first steps while being stigmatized as “mass confinement.”

Doctors performed sloppy brain surgeries, patients had their skulls amputated for no apparent reason, and victims of unfounded treatments like cold and hot water friction and electric shock. Fifty years later, modern psychiatrists are trying to lump all personality traits and existential suffering under the umbrella of illness, and big pharmaceutical companies have made psychiatric drugs like Prozac into household remedies.

The history this book tells is linear.

The story begins with the emergence of a psychiatric hospital in the late 18th century and ends in the quiet examination room of a psychiatrist in the late 20th century.

Freudian theory, which has dominated psychiatry for the past half-century, is disappearing like the last snow of winter.

It is time to take a fresh look at the history of psychiatry.

The trend of viewing mental illness as originating in the brain has reached a biological perspective in our time that places top priority on the brain.

Moreover, the history this book writes about is not a history of intellect, but a social history that vividly restores forgotten figures.

We will focus on how psychiatry has influenced and interacted with culture.

It will show how culture and commerce have infiltrated events often portrayed as triumphs of pure science.

The original version of this book, A History of Psychiatry, was published in 1997, and the Korean translation was published in 2009.

And in 2020, a revised edition of the translation will be published.

There is an interval of about 10 years.

If we consider psychiatry in 2009 as quantitatively expanding and broadening its scope from 1997, how will psychiatry in 2020 differ from a decade ago? For over 200 years, psychiatry has pursued the ultimate goal of finding the scientific reality of mental illness, free from the influence of social values and policies.

Does medicine have a responsibility to address the miseries of life beyond illness? At what point does "need" become "want"? (See Translator's Note, p. 545)

index

introduction

Chapter 1: The Birth of Psychiatry

Chapter 2: The Age of the Camps

Chapter 3: The Birth of Biological Psychiatry

Chapter 4: The Age of Neurotic Disorders

Chapter 5: Psychoanalysis and the Break from Psychiatry

Chapter 6: Finding an Alternative

Chapter 7: The Resurgence of Biological Psychiatry

Chapter 8 From Freud to Prozac

Translator's Note

Translator's Note for the Revised Edition

annotation

Search

Chapter 1: The Birth of Psychiatry

Chapter 2: The Age of the Camps

Chapter 3: The Birth of Biological Psychiatry

Chapter 4: The Age of Neurotic Disorders

Chapter 5: Psychoanalysis and the Break from Psychiatry

Chapter 6: Finding an Alternative

Chapter 7: The Resurgence of Biological Psychiatry

Chapter 8 From Freud to Prozac

Translator's Note

Translator's Note for the Revised Edition

annotation

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

Mental illness has existed in every era.

Mental illness, which is as old as human history, is partly biological and partly genetic.

Although not all mental illnesses arise from the nervous system, some are clearly caused by chemical abnormalities in the brain.

And every society has its own way of dealing with mental illness.

---From "Chapter 1: The Birth of Psychiatry"

To cut to the chase, the camps were a failure.

However, this failure did not mean that the biological paradigm as a standard for diagnosing and treating patients had failed.

It means that the good intention of simply trying to treat the patient was crushed to death by surrounding incidents.

At this point, I break with social constructivism, which claims that psychiatry's good intentions are nothing more than a lie and are solely for the purpose of gaining power as a professional.

The history of the concentration camp era is a story of how faith in humanity and the desire for progress were brutally and repeatedly frustrated.

---From "Chapter 2: The Age of the Concentration Camps"

Even medical students viewed mental illness as something that was possessed by the devil, so it was necessary to change the perspective of the general public, who had similar prejudices.

Family physicians had to learn that mental illness was not a curse from the devil, but something they saw in common practice.

There were also huge stakes involved in determining the condition of the many patients I encountered in the clinic, whether they were manic, depressed, had panic disorder, or had dementia, and deciding who was sick, who could be treated at home, and who should be sent to a concentration camp.

Introducing psychiatry to family physicians meant, in another sense, bringing mental illness into the medical field and “medicalizing” it.

---From "Chapter 3: The Birth of Biological Psychiatry"

In 1920, psychiatry began to flourish outside the camps.

The intellectual trend that gave psychiatry its energies and made it flourish was clearly psychoanalysis.

Until then, the center of gravity of history had been located in Europe, so the pulse from Central Europe finally began to spread to the international community.

By the 1930s, the history of psychiatry had undergone a major change.

Because the Nazis, rising in Germany and Austria, began to gradually kill the rich history of scientific psychiatry that had flourished in those lands for a century and a half.

In the midst of the chaos, when prominent Jewish doctors were murdered in the Holocaust or emigrated to other countries, the scientific energy they had accumulated was scattered in all directions.

---From Chapter 5, Psychoanalysis and the Break from Psychiatry

By the late 20th century, psychoanalysis had flowed far beyond the realm of psychiatry and into the spiritual realm of art and literature.

In any case, psychoanalysis no longer enjoys a privileged position in the treatment of mental illness.

What went wrong with psychoanalysis? External factors also played a role, primarily the changing demographics demanding analysis.

However, internal factors also played a significant role.

Lack of flexibility and resistance to incorporating new findings from neuroscience contributed significantly to the decline of psychoanalysis.

And this resistance stemmed from analysts' fear of being proven wrong.

---From Chapter 8, From Freud to Prozac

To quote Eysenck from 1985:

“All science must undergo the discipline of pseudoscience.” “Chemistry had to shake off the shackles of alchemy.

Neuroscience had to break with the dogmatism of phrenology… and psychology and psychiatry had to abandon the pseudoscience of psychoanalysis… and to transform into true science, they had to continue their work without interruption.

Mental illness, which is as old as human history, is partly biological and partly genetic.

Although not all mental illnesses arise from the nervous system, some are clearly caused by chemical abnormalities in the brain.

And every society has its own way of dealing with mental illness.

---From "Chapter 1: The Birth of Psychiatry"

To cut to the chase, the camps were a failure.

However, this failure did not mean that the biological paradigm as a standard for diagnosing and treating patients had failed.

It means that the good intention of simply trying to treat the patient was crushed to death by surrounding incidents.

At this point, I break with social constructivism, which claims that psychiatry's good intentions are nothing more than a lie and are solely for the purpose of gaining power as a professional.

The history of the concentration camp era is a story of how faith in humanity and the desire for progress were brutally and repeatedly frustrated.

---From "Chapter 2: The Age of the Concentration Camps"

Even medical students viewed mental illness as something that was possessed by the devil, so it was necessary to change the perspective of the general public, who had similar prejudices.

Family physicians had to learn that mental illness was not a curse from the devil, but something they saw in common practice.

There were also huge stakes involved in determining the condition of the many patients I encountered in the clinic, whether they were manic, depressed, had panic disorder, or had dementia, and deciding who was sick, who could be treated at home, and who should be sent to a concentration camp.

Introducing psychiatry to family physicians meant, in another sense, bringing mental illness into the medical field and “medicalizing” it.

---From "Chapter 3: The Birth of Biological Psychiatry"

In 1920, psychiatry began to flourish outside the camps.

The intellectual trend that gave psychiatry its energies and made it flourish was clearly psychoanalysis.

Until then, the center of gravity of history had been located in Europe, so the pulse from Central Europe finally began to spread to the international community.

By the 1930s, the history of psychiatry had undergone a major change.

Because the Nazis, rising in Germany and Austria, began to gradually kill the rich history of scientific psychiatry that had flourished in those lands for a century and a half.

In the midst of the chaos, when prominent Jewish doctors were murdered in the Holocaust or emigrated to other countries, the scientific energy they had accumulated was scattered in all directions.

---From Chapter 5, Psychoanalysis and the Break from Psychiatry

By the late 20th century, psychoanalysis had flowed far beyond the realm of psychiatry and into the spiritual realm of art and literature.

In any case, psychoanalysis no longer enjoys a privileged position in the treatment of mental illness.

What went wrong with psychoanalysis? External factors also played a role, primarily the changing demographics demanding analysis.

However, internal factors also played a significant role.

Lack of flexibility and resistance to incorporating new findings from neuroscience contributed significantly to the decline of psychoanalysis.

And this resistance stemmed from analysts' fear of being proven wrong.

---From Chapter 8, From Freud to Prozac

To quote Eysenck from 1985:

“All science must undergo the discipline of pseudoscience.” “Chemistry had to shake off the shackles of alchemy.

Neuroscience had to break with the dogmatism of phrenology… and psychology and psychiatry had to abandon the pseudoscience of psychoanalysis… and to transform into true science, they had to continue their work without interruption.

---From Chapter 8, From Freud to Prozac

Publisher's Review

Where is the line between illness and normal?

Questioning the boundaries of psychiatry

The 19th century, when madmen were sent to asylums,

From the surge in mental illness to the triumph of the biological paradigm

The narrow gap between science and society

A vivid history of psychiatry's dangerous run!

The psychiatrist in the clinic has to wrap his head around it.

To differentiate between everyday pain and diseases requiring treatment, and to allocate limited medical resources.

As market economic logic became more prevalent, passive patients transformed into consumer customers.

The demand for health care raises ethical questions.

It is the ontology of suffering.

Is pain an emotion that should simply disappear? Drugs that dull the stress and unhappiness that accompany pain may actually worsen efforts to improve the situation.

So what kind of suffering can only be addressed by a psychiatrist? In a world where various psychological treatments proliferate, is psychiatry rightfully assigned the role of treating everyday misfortunes? Is the criterion for mental illness normal or subjective discomfort?

Not a heroic tale of overcoming disease

A history that explicitly portrays the medical perspective on humanity.

A revised edition of "A History of Psychiatry," written by Edward Shorter, a renowned Canadian medical historian who examines the history of psychiatry from a social historical perspective, has been published.

The original first edition of this book was published in 1997 and has since become a classic in the field of psychiatry.

Furthermore, it has been evaluated as a book of profound social significance, not simply as a historical textbook for psychiatrists, but as a book that examines the medicalization of the human psyche's existential suffering during the modernization process. The history of psychiatry lies within a different context from the general history of medicine.

Because it cannot exist only as a heroic tale of overcoming disease and developing new treatments.

Psychiatry is a field that fully reveals the medical perspective on humanity, from the madmen who were treated most inhumanely yet were human, to the horrific and humiliating asylums, to the vulgar and inhumane treatments such as cold and hot friction, electric shock, and various shock therapies. The story of this book, which begins with the scenery of a therapeutic asylum in the late 18th century, ends in the quiet consulting room of a psychiatrist in the late 20th century.

This book is full of twists and turns about facts we either knew nothing about or only knew part of, including rebuttals to Foucault's "Great Confinement" claims, the horrific conditions of the early camps, and harsh criticisms of Freud.

It also delves into the recent conspiracy by big pharmaceutical companies to medicalize mental illness, asking where the future of psychiatry lies.

According to the patient records of the camp

Evidence directly refuting Foucault's "Great Confinement"

In his History of Madness, Michel Foucault argues that psychiatry was invented to bureaucratically control social pathology in the process of strengthening control over the people by state power.

On that basis, it is said that there was a “great confinement” throughout Europe at that time.

Foucault's claims became a huge hit among 20th-century intellectuals and served as a mechanism to reinforce prejudice and stigma against psychiatry. According to the author of this book, Foucault's "Great Confinement" is nothing but absurd nonsense.

Foucault says that “psychiatry” was invented by state power, but even in Germany, where state control was strong, the word “psychiatry” did not even exist until the 19th century.

The author also cites numerous historical records and statistics to provide an idea of the number of asylums and inmates at the time.

According to this, even Bicetre, the largest facility in France, was in fact a general hospital, and only 245 lunatics, including epileptics and the mentally retarded, were admitted there. Even in England, which Foucault cited as an example of the "Great Confinement," an 1826 survey showed that only a small number of people were in asylums, whether public or private, and the combined number of patients in Bethlem and St. Luke's hospitals was 500.

Of those in prison, only 53 were classified as insane.

Therefore, the basis for the 'mass confinement' of over 30 million mentally ill people, as Foucault said, is weak.

“Look, look.

"There goes the crazy guy"

Living as a madman in a world without psychiatry

"If a strong man or woman is considered crazy, the village's way of controlling them is to dig a hole in the floor of a hut, push them in, and then cover it so they can't crawl out.

The hole is about 1.5 meters deep… … and most people die inside it.” _ Records of an Irish constituency member, 1817 (page 14)

Mental illness has existed in every era.

Mental illness, as old as human history, is partly biological and partly genetic.

Although ancient Greek physicians cared for the mentally ill and had written guidelines for their care, psychiatry as a specialized medical field did not exist until the late 18th century.

Until the 18th century, the caregivers for the insane were families or villages.

However, the way of 'care' was very rare.

In a time when traditional customs and social roles were paramount, people with mental and emotional illnesses were treated with the most brutal and ruthless cruelty. In 1870, a study was conducted on the condition of mentally ill people in the Swiss canton of Freiburg.

Of the 164 identified mental patients, one-fifth were confined to “cramped, dark, damp places, stinking of filth” or “straw bales covered in their own excrement” due to being chained to air conditioning or lighting.

Having a madman in a household or village was considered shameful, and even if there were asylums, criminal practices (forced isolation) were commonplace at the household level. The United States was no exception.

What social reformer Dorothea Dix found while traveling through rural Massachusetts were “a woman in a cage,” “a mentally retarded man in chains,” “a man who had been locked in a barn for 17 years,” and “four women in a cage with iron bars.”

These anecdotes were not extreme or bizarre situations, but rather typical symptoms of the time.

In the days before psychiatry existed, patients were not treated with leniency, nor were they left to wander about as they pleased.

All they were allowed was barbaric treatment and exile without compassion.

“Even people who seem beyond recovery have the potential to return to society.”

The rise of Enlightenment physicians and the birth of therapeutic asylums

In 1793, the Jacobin government of France entrusted the management of the Bicetre Hospice to the young 38-year-old doctor Philippe Pinel.

Inspired by the Enlightenment and the philosophy of social progress, Pinel developed his reformist ideals of humanitarian care and the possibility of curing mental illness at Bicetre.

Here he gained fame for freeing madmen from their chains, and thanks to this, he became director of the Salpêtrière in 1795 and freed madmen there too.

Philip Pinel's argument was clear.

The camps were supposed to be used therapeutically, and the essence of the camps was to be places for psychological treatment.

He was close to his patients, soothing them with warm baths, and ensuring that they lived diligently and regularly. If France had Philippe Pinel, Germany had Johann Reil of the University of Halle.

The enlightenment thinker Rail, appalled by the horrors of the camps, believed that doctors were the only ones capable of resolving this unfortunate situation, where humanity and civic consciousness were absent.

He emphasized humane treatment, arguing that asylums should be places that provide facilities and supplementary care that families cannot provide, and developed new treatment methods. Thus, as the 18th century progressed, asylums for the insane were gradually transformed into therapeutic asylums.

At that time, there were two conditions necessary for the camp to have a therapeutic effect.

One was an environment with a sense of community, and the other was the doctor-patient relationship.

The method that strengthened the double doctor-patient relationship was called “moral therapy,” and it marked a new historical starting point for the asylum, distinguishing it from the previous “madhouses.”

“No one has ever asked me this!”

Is psychoanalysis a revolution in psychiatry or a historical regression?

Contrary to popular belief, Freud's psychoanalysis was a major "break" in the history of psychiatry that lasted half a century.

During the decades that psychoanalysis dominated psychiatry, psychiatry drifted away from general medicine, and scientific progress stagnated for a long time.

However, the repercussions of this disconnect on the psychiatric community were enormous.

The most significant of these was that it freed psychiatrists from the concentration camps.

Freudian psychoanalysis established psychiatrists as specialists, seeing patients in their own clinics, for the first time in history. The conventional psychiatric community's reaction to psychoanalysis was negative.

Mainstream psychiatrists reacted to Freud's claim that sex was the cause of mental illness by saying, "Freudian sociability is nauseating," and "No experienced psychiatrist can read Freud without feeling disgusted." Contrary to this negative response from academia, middle-class society is enthusiastic about Freud.

The reason for this enthusiasm was that educated, middle-class people suffering from mental distress could see their problems as relatively "cool" problems that could be solved in a couple of hours of counseling in a fancy counseling room, rather than shameful problems that warranted confinement in a "madhouse."

Psychoanalysis has become the latest fad in German society.

Psychoanalysis Becomes a Faith, Taking Over the World

Josef Breuer, who co-wrote Studies on Hysteria with Freud, introduced Freud, who was originally “a neurologist who patients did not come to,” to a Jewish hysterical girl patient to “give him some work.”

Freud became preoccupied with the sexual elements contained in the stories of this girl and a series of other young women, and developed his theory that real-life psychological suffering stemmed from childhood sexual trauma. In 1902, Freud continued to hold weekly Wednesday discussion groups at his home, attracting a following.

The problem was that Freud was so enthusiastic about spreading his doctrine that he tried to transform it into a kind of movement, rather than limiting it to a method of studying the anxious psychological states of patients.

For this group of demanders, the words of the leader, Freud, were like faith, and opposition was impossible.

The reason was simple.

This is because they all relied on the patients sent by Freud for financial gain. The persecution of Jews before and after World War II was a decisive factor in the spread of psychoanalysis around the world.

For European Jewish psychoanalysts who fled Nazi Germany to the United States, America was a new paradise, and trend-conscious Americans quickly became enthusiastic about psychoanalysis.

The exiled Jews saw their psychoanalysis as a kind of "civilizing mission" and a healing gift to the world.

In New York, there is even a term called "New Yorker Syndrome," referring to the desperate need for psychoanalysis.

In fact, in 1932 the American Psychoanalytic Association had 92 members, but by 1968 that number had grown to 1,300.

During the 1960s, the so-called "golden age of American psychoanalysis," there were 20 training institutes and 29 regional associations, and the military even paid for psychoanalytic training for psychiatrists serving in the military.

“Let’s try one last time with a higher bolt.”

Lobotomy and electroconvulsive therapy...

The Cruel History of Mental Experiments

The basic idea of biological psychiatry is that mental disorders are not simply diseases of the mind, but biological abnormalities caused by specific dysfunctions in the brain.

This began to slowly emerge towards the end of the early camp period.

Of course, even before the modern era, there were surgical treatments such as 'cutting it open first', saying that mental illness was caused by the 'stone of madness' in the head of a madman.

However, this was an era of "myth," not "science." Early surgical procedures were crude and dangerous.

In particular, Egas Moniz, winner of the 1949 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, brutally abused the human brain through 'lobotomy', which destroys part of the brain lobe.

Walter Freeman, an American who was influenced by Moniz, also developed a technique called transorbital lobotomy, which involves inserting an instrument into the brain through the roof of the eye to resect the brain.

Although lobotomy was effective in calming down the violent patients who were difficult to manage, it usually caused loss of judgment and social functioning, and made the patient dull in his or her ability to perceive social situations and become inappropriately repressed. In the 1930s, treatments such as insulin coma therapy, which involved inducing a coma with insulin and then waking the patient up, and metrazol convulsion therapy, which attempted to improve symptoms by inducing convulsions with injections of metrazol, became popular.

And then there was electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), first used in 1938 by Ugo Cerletti of the University of Rome.

This was a method of inducing a seizure by sending an electrical shock to the brain.

Once again, a “click-” electrical noise was heard.

The patient lay motionless and began to sing. “Let’s try one last time with a higher voltage,” the patient said.

"look.

“The first one was annoying, and the second one almost killed me.” The practitioners looked at each other in bewilderment. “Okay, let’s continue.

“Leave it alone,” said Cherleti. The practitioner turned up the power of his equipment to its maximum.

After the third shock, the patient began to have typical grand mal seizures, with rhythmic muscle contractions and relaxations.

My breathing stopped.

His face turned pale, his heartbeat became rapid, and his pupillary reflex disappeared.

After 48 seconds, the patient exhaled deeply.

The doctors also took a deep breath.

They had just determined the amount of electricity that could safely induce convulsions in humans.

(Page 361)

Electroshock therapy was clearly not a cure for schizophrenia.

However, it has been described as alleviating symptoms and helping the individual to function to some extent.

And this soon spread rapidly throughout the world.

By 1959, electroconvulsive therapy had become an “essential treatment” for patients with bipolar disorder and major depression.

It was effective, quick, and the patients didn't mind it.

However, electroshock therapy became a catalyst for reinforcing the negative image of psychiatry.

The emergence of psychoanalysis and the development of psychopharmacology played a major role in this.

Compared to lying on a luxurious sofa and talking to a well-dressed psychoanalyst, compared to a simple prescription for a packet of medication, electroshock therapy was both highly uncertain and, above all, extremely inhumane.

“Prozac will rule the world!”

Psychopharmacology and the Emergence of Big Pharma

Suffering from a mental illness was once an insult not only to the individual, but also to the family and community.

But the birth of the term "neuroticism" and Freudian psychoanalysis obscured its shamefulness, and by the time Prozac received FDA approval in 1987, it had become a well-educated, middle-class fad.

The emergence of psychotropic drugs, such as Prozac, was called 'cosmetic psychopharmacology' and helped to remove the stigma attached to mental illness.

Now, the urban middle class no longer tried to hide their psychological pain and existential angst, and they shared their 'Prozac experiences' at dinner parties.

The word beginning with 'P' is no longer psychoanalysis, but now prozac. In fact, the first psychiatric drug that the American public was crazy about was a tranquilizer called 'Miltown.'

This drug, introduced in articles as a "drug of happiness" or a "drug for peace of mind," quickly swept the United States.

A 1956 survey found that one in 20 Americans took the drug.

In 1970, one in five American women and one in 13 American men used "mild tranquilizers and sedatives."

Since then, the prescription of psychotropic drugs has continued to increase. In 1975, 25.2% of patients per clinic received a prescription, but by 1990, 50.2% of patients received a prescription. After this, a series of psychotropic drugs, including Prozac, further expanded their influence thanks to the marketing power of pharmaceutical companies.

Since the 1960s, American psychiatry has defined simple feelings of unhappiness, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbances as depression, and depression diagnoses have begun to be given to young children as well.

The boys' boisterous behavior was diagnosed as ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), and they were prescribed a drug called Ritalin.

Even common childhood fears of ghosts were given psychiatric diagnoses and prescribed medications. The psychiatric community, lobbied by the giant pharmaceutical companies that dominate psychopharmacology, constantly created new diagnoses, and the pharmaceutical companies steadily produced selective treatments to match these new diagnoses.

As the threshold for illness, which determines a level above which illness is diagnosed, has steadily decreased, the range of psychiatric patients has increased unprecedentedly.

And those who sought out psychiatrists were not there for a couple of hours of interviews, but simply to get a prescription that suited them.

Psychiatrists have been reduced to just people who prescribe magical drugs.

Questioning the boundaries of psychiatry

The 19th century, when madmen were sent to asylums,

From the surge in mental illness to the triumph of the biological paradigm

The narrow gap between science and society

A vivid history of psychiatry's dangerous run!

The psychiatrist in the clinic has to wrap his head around it.

To differentiate between everyday pain and diseases requiring treatment, and to allocate limited medical resources.

As market economic logic became more prevalent, passive patients transformed into consumer customers.

The demand for health care raises ethical questions.

It is the ontology of suffering.

Is pain an emotion that should simply disappear? Drugs that dull the stress and unhappiness that accompany pain may actually worsen efforts to improve the situation.

So what kind of suffering can only be addressed by a psychiatrist? In a world where various psychological treatments proliferate, is psychiatry rightfully assigned the role of treating everyday misfortunes? Is the criterion for mental illness normal or subjective discomfort?

Not a heroic tale of overcoming disease

A history that explicitly portrays the medical perspective on humanity.

A revised edition of "A History of Psychiatry," written by Edward Shorter, a renowned Canadian medical historian who examines the history of psychiatry from a social historical perspective, has been published.

The original first edition of this book was published in 1997 and has since become a classic in the field of psychiatry.

Furthermore, it has been evaluated as a book of profound social significance, not simply as a historical textbook for psychiatrists, but as a book that examines the medicalization of the human psyche's existential suffering during the modernization process. The history of psychiatry lies within a different context from the general history of medicine.

Because it cannot exist only as a heroic tale of overcoming disease and developing new treatments.

Psychiatry is a field that fully reveals the medical perspective on humanity, from the madmen who were treated most inhumanely yet were human, to the horrific and humiliating asylums, to the vulgar and inhumane treatments such as cold and hot friction, electric shock, and various shock therapies. The story of this book, which begins with the scenery of a therapeutic asylum in the late 18th century, ends in the quiet consulting room of a psychiatrist in the late 20th century.

This book is full of twists and turns about facts we either knew nothing about or only knew part of, including rebuttals to Foucault's "Great Confinement" claims, the horrific conditions of the early camps, and harsh criticisms of Freud.

It also delves into the recent conspiracy by big pharmaceutical companies to medicalize mental illness, asking where the future of psychiatry lies.

According to the patient records of the camp

Evidence directly refuting Foucault's "Great Confinement"

In his History of Madness, Michel Foucault argues that psychiatry was invented to bureaucratically control social pathology in the process of strengthening control over the people by state power.

On that basis, it is said that there was a “great confinement” throughout Europe at that time.

Foucault's claims became a huge hit among 20th-century intellectuals and served as a mechanism to reinforce prejudice and stigma against psychiatry. According to the author of this book, Foucault's "Great Confinement" is nothing but absurd nonsense.

Foucault says that “psychiatry” was invented by state power, but even in Germany, where state control was strong, the word “psychiatry” did not even exist until the 19th century.

The author also cites numerous historical records and statistics to provide an idea of the number of asylums and inmates at the time.

According to this, even Bicetre, the largest facility in France, was in fact a general hospital, and only 245 lunatics, including epileptics and the mentally retarded, were admitted there. Even in England, which Foucault cited as an example of the "Great Confinement," an 1826 survey showed that only a small number of people were in asylums, whether public or private, and the combined number of patients in Bethlem and St. Luke's hospitals was 500.

Of those in prison, only 53 were classified as insane.

Therefore, the basis for the 'mass confinement' of over 30 million mentally ill people, as Foucault said, is weak.

“Look, look.

"There goes the crazy guy"

Living as a madman in a world without psychiatry

"If a strong man or woman is considered crazy, the village's way of controlling them is to dig a hole in the floor of a hut, push them in, and then cover it so they can't crawl out.

The hole is about 1.5 meters deep… … and most people die inside it.” _ Records of an Irish constituency member, 1817 (page 14)

Mental illness has existed in every era.

Mental illness, as old as human history, is partly biological and partly genetic.

Although ancient Greek physicians cared for the mentally ill and had written guidelines for their care, psychiatry as a specialized medical field did not exist until the late 18th century.

Until the 18th century, the caregivers for the insane were families or villages.

However, the way of 'care' was very rare.

In a time when traditional customs and social roles were paramount, people with mental and emotional illnesses were treated with the most brutal and ruthless cruelty. In 1870, a study was conducted on the condition of mentally ill people in the Swiss canton of Freiburg.

Of the 164 identified mental patients, one-fifth were confined to “cramped, dark, damp places, stinking of filth” or “straw bales covered in their own excrement” due to being chained to air conditioning or lighting.

Having a madman in a household or village was considered shameful, and even if there were asylums, criminal practices (forced isolation) were commonplace at the household level. The United States was no exception.

What social reformer Dorothea Dix found while traveling through rural Massachusetts were “a woman in a cage,” “a mentally retarded man in chains,” “a man who had been locked in a barn for 17 years,” and “four women in a cage with iron bars.”

These anecdotes were not extreme or bizarre situations, but rather typical symptoms of the time.

In the days before psychiatry existed, patients were not treated with leniency, nor were they left to wander about as they pleased.

All they were allowed was barbaric treatment and exile without compassion.

“Even people who seem beyond recovery have the potential to return to society.”

The rise of Enlightenment physicians and the birth of therapeutic asylums

In 1793, the Jacobin government of France entrusted the management of the Bicetre Hospice to the young 38-year-old doctor Philippe Pinel.

Inspired by the Enlightenment and the philosophy of social progress, Pinel developed his reformist ideals of humanitarian care and the possibility of curing mental illness at Bicetre.

Here he gained fame for freeing madmen from their chains, and thanks to this, he became director of the Salpêtrière in 1795 and freed madmen there too.

Philip Pinel's argument was clear.

The camps were supposed to be used therapeutically, and the essence of the camps was to be places for psychological treatment.

He was close to his patients, soothing them with warm baths, and ensuring that they lived diligently and regularly. If France had Philippe Pinel, Germany had Johann Reil of the University of Halle.

The enlightenment thinker Rail, appalled by the horrors of the camps, believed that doctors were the only ones capable of resolving this unfortunate situation, where humanity and civic consciousness were absent.

He emphasized humane treatment, arguing that asylums should be places that provide facilities and supplementary care that families cannot provide, and developed new treatment methods. Thus, as the 18th century progressed, asylums for the insane were gradually transformed into therapeutic asylums.

At that time, there were two conditions necessary for the camp to have a therapeutic effect.

One was an environment with a sense of community, and the other was the doctor-patient relationship.

The method that strengthened the double doctor-patient relationship was called “moral therapy,” and it marked a new historical starting point for the asylum, distinguishing it from the previous “madhouses.”

“No one has ever asked me this!”

Is psychoanalysis a revolution in psychiatry or a historical regression?

Contrary to popular belief, Freud's psychoanalysis was a major "break" in the history of psychiatry that lasted half a century.

During the decades that psychoanalysis dominated psychiatry, psychiatry drifted away from general medicine, and scientific progress stagnated for a long time.

However, the repercussions of this disconnect on the psychiatric community were enormous.

The most significant of these was that it freed psychiatrists from the concentration camps.

Freudian psychoanalysis established psychiatrists as specialists, seeing patients in their own clinics, for the first time in history. The conventional psychiatric community's reaction to psychoanalysis was negative.

Mainstream psychiatrists reacted to Freud's claim that sex was the cause of mental illness by saying, "Freudian sociability is nauseating," and "No experienced psychiatrist can read Freud without feeling disgusted." Contrary to this negative response from academia, middle-class society is enthusiastic about Freud.

The reason for this enthusiasm was that educated, middle-class people suffering from mental distress could see their problems as relatively "cool" problems that could be solved in a couple of hours of counseling in a fancy counseling room, rather than shameful problems that warranted confinement in a "madhouse."

Psychoanalysis has become the latest fad in German society.

Psychoanalysis Becomes a Faith, Taking Over the World

Josef Breuer, who co-wrote Studies on Hysteria with Freud, introduced Freud, who was originally “a neurologist who patients did not come to,” to a Jewish hysterical girl patient to “give him some work.”

Freud became preoccupied with the sexual elements contained in the stories of this girl and a series of other young women, and developed his theory that real-life psychological suffering stemmed from childhood sexual trauma. In 1902, Freud continued to hold weekly Wednesday discussion groups at his home, attracting a following.

The problem was that Freud was so enthusiastic about spreading his doctrine that he tried to transform it into a kind of movement, rather than limiting it to a method of studying the anxious psychological states of patients.

For this group of demanders, the words of the leader, Freud, were like faith, and opposition was impossible.

The reason was simple.

This is because they all relied on the patients sent by Freud for financial gain. The persecution of Jews before and after World War II was a decisive factor in the spread of psychoanalysis around the world.

For European Jewish psychoanalysts who fled Nazi Germany to the United States, America was a new paradise, and trend-conscious Americans quickly became enthusiastic about psychoanalysis.

The exiled Jews saw their psychoanalysis as a kind of "civilizing mission" and a healing gift to the world.

In New York, there is even a term called "New Yorker Syndrome," referring to the desperate need for psychoanalysis.

In fact, in 1932 the American Psychoanalytic Association had 92 members, but by 1968 that number had grown to 1,300.

During the 1960s, the so-called "golden age of American psychoanalysis," there were 20 training institutes and 29 regional associations, and the military even paid for psychoanalytic training for psychiatrists serving in the military.

“Let’s try one last time with a higher bolt.”

Lobotomy and electroconvulsive therapy...

The Cruel History of Mental Experiments

The basic idea of biological psychiatry is that mental disorders are not simply diseases of the mind, but biological abnormalities caused by specific dysfunctions in the brain.

This began to slowly emerge towards the end of the early camp period.

Of course, even before the modern era, there were surgical treatments such as 'cutting it open first', saying that mental illness was caused by the 'stone of madness' in the head of a madman.

However, this was an era of "myth," not "science." Early surgical procedures were crude and dangerous.

In particular, Egas Moniz, winner of the 1949 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, brutally abused the human brain through 'lobotomy', which destroys part of the brain lobe.

Walter Freeman, an American who was influenced by Moniz, also developed a technique called transorbital lobotomy, which involves inserting an instrument into the brain through the roof of the eye to resect the brain.

Although lobotomy was effective in calming down the violent patients who were difficult to manage, it usually caused loss of judgment and social functioning, and made the patient dull in his or her ability to perceive social situations and become inappropriately repressed. In the 1930s, treatments such as insulin coma therapy, which involved inducing a coma with insulin and then waking the patient up, and metrazol convulsion therapy, which attempted to improve symptoms by inducing convulsions with injections of metrazol, became popular.

And then there was electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), first used in 1938 by Ugo Cerletti of the University of Rome.

This was a method of inducing a seizure by sending an electrical shock to the brain.

Once again, a “click-” electrical noise was heard.

The patient lay motionless and began to sing. “Let’s try one last time with a higher voltage,” the patient said.

"look.

“The first one was annoying, and the second one almost killed me.” The practitioners looked at each other in bewilderment. “Okay, let’s continue.

“Leave it alone,” said Cherleti. The practitioner turned up the power of his equipment to its maximum.

After the third shock, the patient began to have typical grand mal seizures, with rhythmic muscle contractions and relaxations.

My breathing stopped.

His face turned pale, his heartbeat became rapid, and his pupillary reflex disappeared.

After 48 seconds, the patient exhaled deeply.

The doctors also took a deep breath.

They had just determined the amount of electricity that could safely induce convulsions in humans.

(Page 361)

Electroshock therapy was clearly not a cure for schizophrenia.

However, it has been described as alleviating symptoms and helping the individual to function to some extent.

And this soon spread rapidly throughout the world.

By 1959, electroconvulsive therapy had become an “essential treatment” for patients with bipolar disorder and major depression.

It was effective, quick, and the patients didn't mind it.

However, electroshock therapy became a catalyst for reinforcing the negative image of psychiatry.

The emergence of psychoanalysis and the development of psychopharmacology played a major role in this.

Compared to lying on a luxurious sofa and talking to a well-dressed psychoanalyst, compared to a simple prescription for a packet of medication, electroshock therapy was both highly uncertain and, above all, extremely inhumane.

“Prozac will rule the world!”

Psychopharmacology and the Emergence of Big Pharma

Suffering from a mental illness was once an insult not only to the individual, but also to the family and community.

But the birth of the term "neuroticism" and Freudian psychoanalysis obscured its shamefulness, and by the time Prozac received FDA approval in 1987, it had become a well-educated, middle-class fad.

The emergence of psychotropic drugs, such as Prozac, was called 'cosmetic psychopharmacology' and helped to remove the stigma attached to mental illness.

Now, the urban middle class no longer tried to hide their psychological pain and existential angst, and they shared their 'Prozac experiences' at dinner parties.

The word beginning with 'P' is no longer psychoanalysis, but now prozac. In fact, the first psychiatric drug that the American public was crazy about was a tranquilizer called 'Miltown.'

This drug, introduced in articles as a "drug of happiness" or a "drug for peace of mind," quickly swept the United States.

A 1956 survey found that one in 20 Americans took the drug.

In 1970, one in five American women and one in 13 American men used "mild tranquilizers and sedatives."

Since then, the prescription of psychotropic drugs has continued to increase. In 1975, 25.2% of patients per clinic received a prescription, but by 1990, 50.2% of patients received a prescription. After this, a series of psychotropic drugs, including Prozac, further expanded their influence thanks to the marketing power of pharmaceutical companies.

Since the 1960s, American psychiatry has defined simple feelings of unhappiness, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbances as depression, and depression diagnoses have begun to be given to young children as well.

The boys' boisterous behavior was diagnosed as ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), and they were prescribed a drug called Ritalin.

Even common childhood fears of ghosts were given psychiatric diagnoses and prescribed medications. The psychiatric community, lobbied by the giant pharmaceutical companies that dominate psychopharmacology, constantly created new diagnoses, and the pharmaceutical companies steadily produced selective treatments to match these new diagnoses.

As the threshold for illness, which determines a level above which illness is diagnosed, has steadily decreased, the range of psychiatric patients has increased unprecedentedly.

And those who sought out psychiatrists were not there for a couple of hours of interviews, but simply to get a prescription that suited them.

Psychiatrists have been reduced to just people who prescribe magical drugs.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of publication: December 7, 2020

- Page count, weight, size: 660 pages | 948g | 153*225*35mm

- ISBN13: 9791189932909

- ISBN10: 1189932903

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)