The Evolution of Investment

|

Description

Book Introduction

It gave birth to today's global companies such as Apple, Google, Facebook, and Alibaba.

If you want to know the secrets of venture capitalists, this is the one book you must read!

Just because you start a business with technology or an idea, that doesn't mean the business will survive.

What is needed above all else is funds to maintain and develop the business.

Venture capitalists provide entrepreneurs with the necessary funding to help them create new worlds.

Venture capitalists were also present at the start of today's global companies, such as Apple, Google, Facebook, and Alibaba.

So how did venture investment begin, and what processes led to the creation of today's global companies? Sebastian Mallaby, a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist who boasts exceptional research and writing skills, vividly illustrates the frustrations and failures that shaped the venture capital industry, Silicon Valley, the broader technology sector, and the world as a whole.

From the dawn of venture capital in the mid-20th century to its current role in shaking up the global economy, this book will reveal the mindset of venture capitalists, how they invest, and how they have changed the world.

If you want to know the secrets of venture capitalists, this is the one book you must read!

Just because you start a business with technology or an idea, that doesn't mean the business will survive.

What is needed above all else is funds to maintain and develop the business.

Venture capitalists provide entrepreneurs with the necessary funding to help them create new worlds.

Venture capitalists were also present at the start of today's global companies, such as Apple, Google, Facebook, and Alibaba.

So how did venture investment begin, and what processes led to the creation of today's global companies? Sebastian Mallaby, a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist who boasts exceptional research and writing skills, vividly illustrates the frustrations and failures that shaped the venture capital industry, Silicon Valley, the broader technology sector, and the world as a whole.

From the dawn of venture capital in the mid-20th century to its current role in shaking up the global economy, this book will reveal the mindset of venture capitalists, how they invest, and how they have changed the world.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Preface: The Irrational Person

Chapter 1: Arthur Locke and Liberated Capital

Chapter 2: No Finance

Chapter 3: Sequoia Capital, Kleiner Perkins, and Activist Investing

Chapter 4 Apple's Whispers

Chapter 5: Cisco, 3Com, and Silicon Valley's Leap Forward

Chapter 6: The Planner and the Improviser

Chapter 7: Benchmarks, Softbank, and "Everyone Needs $100 Million"

Chapter 8: Money for Google, Some Free Money

Chapter 9: Peter Thiel, Y Combinator, and the Rebellion of Silicon Valley Youth

Chapter 10: Just go to China and stir up money.

Chapter 11: Axel, Facebook, and the Decline of Kleiner Perkins

Chapter 12: Russians, Tiger Global, and the Rise of Growth

Chapter 13: Sequoia Capital: The Power of the Many

Chapter 14: Poker with the Unicorn

Conclusion: Luck, Capability, and Competition Between Nations

Acknowledgements

chart

Chronology

annotation

Search

Chapter 1: Arthur Locke and Liberated Capital

Chapter 2: No Finance

Chapter 3: Sequoia Capital, Kleiner Perkins, and Activist Investing

Chapter 4 Apple's Whispers

Chapter 5: Cisco, 3Com, and Silicon Valley's Leap Forward

Chapter 6: The Planner and the Improviser

Chapter 7: Benchmarks, Softbank, and "Everyone Needs $100 Million"

Chapter 8: Money for Google, Some Free Money

Chapter 9: Peter Thiel, Y Combinator, and the Rebellion of Silicon Valley Youth

Chapter 10: Just go to China and stir up money.

Chapter 11: Axel, Facebook, and the Decline of Kleiner Perkins

Chapter 12: Russians, Tiger Global, and the Rise of Growth

Chapter 13: Sequoia Capital: The Power of the Many

Chapter 14: Poker with the Unicorn

Conclusion: Luck, Capability, and Competition Between Nations

Acknowledgements

chart

Chronology

annotation

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

Bill Gurley of Benchmark once said:

“Venture capital is not a business that aims for a one-run home run.

“It’s a business that aims for a Grand Slam.”

This means that venture capitalists must be ambitious.

Julian Robertson, a famous hedge fund manager, used to say that he could find stocks that would double in value within three years.

This is a great result in his eyes.

But if venture capitalists pursue the same goals, almost all of them will fail.

According to the power law, relatively few startups will ever see their valuations merely double.

If the majority of companies go bankrupt and their stock values become zero, it would be a huge disaster for stock market investors.

But every year there are a few outliers who produce notable Grand Slams.

And the only important thing for venture capitalists is to catch them.

Today, venture capitalists are following this power-law logic as they back flying cars, space tourism, and AI systems that write movie scripts.

They look beyond the horizon and pursue high-risk, high-reward opportunities that many believe are unlikely to materialize.

Thiel speaks with passion and contempt for gradualism:

“We can cure cancer, dementia, all diseases associated with aging, and the decline of metabolic function.

We can develop means to travel much faster to anywhere on Earth.

We could even develop the technology to leave Earth and settle somewhere new.” Of course, investing in something absolutely impossible would be a waste of resources.

But a common mistake we humans make is investing too cautiously, investing in obvious ideas that others can easily copy and ultimately make little profit.

--- p.21~22

This book has two main goals.

The first goal is to explain the mindset of a venture capitalist.

There are quite a few books that focus on the history of Silicon Valley, focusing on inventors and entrepreneurs.

However, these books left much to be desired when it came to understanding the minds of those who raise funds and build businesses.

This book closely examines investments in world-renowned companies, from Apple to Cisco, WhatsApp to Uber, demonstrating what happens when venture capitalists engage with startups and how venture capital differs from other forms of capital.

Financiers allocate scarce capital based on quantitative analysis.

Venture capitalists are interested in meeting people, engaging them, and not spreadsheets.

Financiers evaluate a company's value by looking at its cash flow.

Venture capitalists often back startups before even analyzing their cash flow.

Financiers trade millions of dollars in financial assets in the blink of an eye.

Venture capitalists own relatively small stakes in companies.

At its most fundamental, financiers forecast future trends based on past data, ignoring the risk of unusual events that are highly unlikely to occur.

Venture capitalists seek a radical departure from the past.

They only pay attention to unusual events.

A second goal of this book is to assess the social impact of venture capitalists.

Venture capitalists claim they are making the world a better place.

This is certainly true sometimes.

Impossible Foods is a case in point.

But while video games and social media provide entertainment, information, and allow grandmothers to see their grandchildren from afar, they also foster screen addiction and fake news.

--- p.29~30

The 1957 revolt was made possible by a new form of finance, initially called adventure capital.

This capital was intended to back engineers who were too risky and poor to qualify for conventional bank loans, but whose bold inventions promised the potential for huge returns for investors.

Perhaps the funding of Fairchild Semiconductor, founded by the eight rebels, was the first such venture on the West Coast, and it changed the course of history for the region.

Since Fairchild Semiconductor raised $1.4 million in funding, any team with a big idea and a strong ambition in Silicon Valley has been able to branch out and form a new company, creating the organizational structure that best suits them.

This new capital allowed engineers, inventors, activists, and artistic visionaries to meet, combine, separate, compete, and collaborate.

Sometimes venture capital becomes renegade capital, sometimes it becomes team-building capital, and sometimes it becomes simply experimental capital.

But no matter how you look at it, talents were liberated and a revolution occurred.

--- p.36

It's time for Rock to move on to the next thing.

His company, like the Eight Rebels, made a decent profit of about $700,000, or 600 times its investment.

But I felt that Rock could do better than this.

Although he did close the deal, most of the profits went to Fairchild Camera & Instruments.

Rock tried to protect the eight scientists, but only partially.

But what he did was prove that liberation capital does much more than allow eight rebels to start their own company and continue to work as a team.

Liberated capital was about unleashing human talent.

It was about reinforcing incentives.

It was creating a new kind of applied science and commercial culture.

--- p.68

Valentine made a decision at the end of 1974, a few weeks after visiting the Atari factory.

He decided not to invest right away.

Because Atari was so confusing.

But I wasn't going to let go.

Because Atari's potential was so great.

Instead, we'll approach our relationship with Atari carefully and step by step, starting by rolling up our sleeves and writing the Atari business plan.

After everything went smoothly (Bushnell had bought into his strategy and the business plan had caught the attention of other venture capitalists), Valentine planned to invest.

In other words, he would only invest money if Atari's risks were at least partially eliminated.

So, to support a company with a hot tub culture, we had to combine activism and incrementalism.

--- p.107

Yet, when Apple was raising funds, the stars of the venture capital industry failed to seize the opportunity.

This shows that even the best venture capitalists can make big mistakes.

Tom Perkins and Eugene Kleiner refused to even meet Jobs.

Bill Draper of Sutter Hill Ventures sent an employee to Apple, but was so displeased when he heard reports that Jobs and Wozniak had kept his employee waiting that he lost interest.

Meanwhile, Fitch Johnson, who previously worked with Draper as an SBIC partner, said this:

“How can you have a computer at home? You want to put cookbooks on it?” Jobs kept getting rejected, and then he reached out to Stan Veit, who ran the first computer retail store in faraway New York.

Jobs offered Byte a 10 percent stake in Apple if he invested just $10,000.

Byte recalled with regret:

“I looked at the long-haired hippie youth and his friends and thought,

“If you were the last person left in the world, I could give you $10,000.” Jobs offered Nolan Bushnell, who had hired him at Atari, $50,000 to invest in Apple and get a third of the company.

Bushnell remembers:

“I was so smart that I said, ‘No.’

It's funny when I think about that time.

“When I’m not crying.”

Fortunately for Jobs and Wozniak, by 1976 a large venture capital network had already been established in Silicon Valley, so they didn't have to despair if they were rejected by many.

Soon after, the two found their way to Don Valentine of Sequoia Capital.

--- p.137~138

Before the Yahoo team could reach a conclusion, Son made a second, more radical move.

He asked Moritz and the founders who Yahoo's main competitors were.

They answered like this.

“It’s Excite and Lycos.”

Son Jeong-ui instructed one of his secretaries:

“Take it and write it down.”

Then he said to Moritz and the founders:

“If I don’t invest in Yahoo, I’ll invest in Excite and Lycos and ruin Yahoo.”

For Yang and Philo, and especially for Moritz, Son's threat was a kind of divine revelation.

In the competition to become the most sought-after internet guide, there will be only one winner, and an investor with $100 million to write a check will get to choose who will win.

Like the Don Corleone of the digital world, Son made Moritz an offer he couldn't refuse.

Moritz later resolved never to be in that position again.

--- p.259~260

As summer wore on, Brin and Page rowed back to Door.

They said to the door:

“I have some surprising news for you.

“We have decided to accept your idea.” Now they wanted to bring in a CEO from outside, and they even went so far as to name the person they wanted.

There was only one person who met their standards.

Brin and Page said:

“We want Steve Jobs.”

It was impossible to recruit Jobs.

The door hurried to find an alternative.

He sometimes described himself as “an ordinary scout, contrary to what people say.”

He argued that the nature of venture capital has not changed since the days of Arthur Locke and Tommy Davis.

“We don’t invest based on business plans.

I don't invest based on cash flow.

We invest in people.” Doerr started to network to find executives with computer science backgrounds, but his first choice wasn’t willing to entrust his future to the latest search engine.

Then, in October 2000, Door set his sights on another computer scientist turned executive.

That man was Eric Schmidt, and he was running a software company called Novell.

--- p.305

A day or so later, Levchin met Musk.

Musk said mockingly:

“The reason we decided 6 to 4 is because we were very considerate of you.

As you can see, you made a huge deal.

“An unfair merger like this is nothing short of a windfall for you.”

Levchin turned around with a faint smile and complained to Till on the phone.

“It's all over.

I will not do this kind of deal.

I feel terribly insulted.

“I can’t stand it.” He left the office briskly and walked home.

Harris heard that Levchin had kicked him out.

Harris, who took a position at X.com at Moritz's request, was particularly conscious of shareholders who valued cooperation over competition.

He left the office in a hurry and went to see Levchin.

Levchin took refuge in the apartment's laundry room.

There was an old washing machine there, made by a company with the amusing name of WEB.

This old washing machine requires a quarter to operate.

Harris appealed to Rebchin to reconsider his decision while helping him fold the clothes.

He pleaded with Musk to forget the insult he had recently received with the 6-4 vote.

He and the X.com board only respected Levchin.

In fact, he came with a proposal to appease Levchin, to show that he was sincere.

It was supposed to be 5 vs 5.

Finally, Levchin changed his mind and the merger went ahead.

Musk lost a lot of money by needlessly mocking his opponents.

--- p.333~334

Thiel met Musk, a longtime rival since the PayPal days, by chance at a friend's wedding.

Relations between the two weren't always smooth, given that Thiel's comrades forced Musk out of PayPal.

But Musk was moving on from his bad days at PayPal by investing his share of the profits in two new startups: Tesla, which makes electric cars, and SpaceX, which boasted noble ambitions of drastically reducing the cost of space transportation enough to establish new colonies on Mars.

At the wedding, Musk encouraged Thiel to invest in SpaceX.

Till said this:

“Of course.

“Let’s forget the past.”

--- p.349

It was no surprise that Milner was a huge success.

As he predicted, Facebook's user base and revenue exploded.

By the end of 2010, a year and a half later, Facebook's valuation had reached $50 billion. DST had generated over $1.5 billion in revenue, and Facebook's valuation continued to soar.

In Silicon Valley, this became a watershed moment.

13 years ago, Masayoshi Son surprised traditional venture capitalists by investing $100 million in Yahoo.

In contrast, Milner initially purchased over $300 million worth of Facebook stock.

Meanwhile, Son provided what amounted to bridge financing ahead of Yahoo's stock market debut.

Milner's investment was so substantial that Zuckerberg didn't need to immediately launch an initial public offering. DST's investment met both Facebook's growth capital needs and its employees' liquidity needs.

It was a signal that unlisted technology companies could delay their initial public offerings for about three years.

As a result, private investors were able to create enormous wealth and reap monopolistic profits by leaving the stock market.

Along with this, Milner's investment in Facebook heralds a phase in which entrepreneurs' power will be strengthened more than ever before.

Peter Thiel ran his venture capital firm on Sand Hill Road as a founder-friendly alternative, but Milner took the concept to a whole new level.

He invested in later stages and invested much more money.

It was surprising that he was willing to risk hundreds of millions of dollars while giving up any say in the company.

And while Thiel's respect for founders was based on an understanding of power laws, Milner's was, simply put, based on compromise.

He invested in companies that were qualified to go public in terms of size and sophistication.

So he will act like a stock market investor.

And that too in a passive manner.

--- p.455~456

The apparent success of venture capital-backed companies sometimes raises one question:

Does venture capital create success, or does it simply appear where success already exists? However, as we've already seen, there's research showing that startups supported by venture capital outperform other startups, and this book illustrates numerous instances where venture capital positively impacts portfolio companies.

Even if venture capital's capabilities depend solely on selecting companies to invest in, rather than guiding startups, these capabilities are still valuable.

Making smart choices about which companies to invest in increases the likelihood that the most promising startups will secure the funding they need.

It ensures that society's savings are allocated productively.

“Venture capital is not a business that aims for a one-run home run.

“It’s a business that aims for a Grand Slam.”

This means that venture capitalists must be ambitious.

Julian Robertson, a famous hedge fund manager, used to say that he could find stocks that would double in value within three years.

This is a great result in his eyes.

But if venture capitalists pursue the same goals, almost all of them will fail.

According to the power law, relatively few startups will ever see their valuations merely double.

If the majority of companies go bankrupt and their stock values become zero, it would be a huge disaster for stock market investors.

But every year there are a few outliers who produce notable Grand Slams.

And the only important thing for venture capitalists is to catch them.

Today, venture capitalists are following this power-law logic as they back flying cars, space tourism, and AI systems that write movie scripts.

They look beyond the horizon and pursue high-risk, high-reward opportunities that many believe are unlikely to materialize.

Thiel speaks with passion and contempt for gradualism:

“We can cure cancer, dementia, all diseases associated with aging, and the decline of metabolic function.

We can develop means to travel much faster to anywhere on Earth.

We could even develop the technology to leave Earth and settle somewhere new.” Of course, investing in something absolutely impossible would be a waste of resources.

But a common mistake we humans make is investing too cautiously, investing in obvious ideas that others can easily copy and ultimately make little profit.

--- p.21~22

This book has two main goals.

The first goal is to explain the mindset of a venture capitalist.

There are quite a few books that focus on the history of Silicon Valley, focusing on inventors and entrepreneurs.

However, these books left much to be desired when it came to understanding the minds of those who raise funds and build businesses.

This book closely examines investments in world-renowned companies, from Apple to Cisco, WhatsApp to Uber, demonstrating what happens when venture capitalists engage with startups and how venture capital differs from other forms of capital.

Financiers allocate scarce capital based on quantitative analysis.

Venture capitalists are interested in meeting people, engaging them, and not spreadsheets.

Financiers evaluate a company's value by looking at its cash flow.

Venture capitalists often back startups before even analyzing their cash flow.

Financiers trade millions of dollars in financial assets in the blink of an eye.

Venture capitalists own relatively small stakes in companies.

At its most fundamental, financiers forecast future trends based on past data, ignoring the risk of unusual events that are highly unlikely to occur.

Venture capitalists seek a radical departure from the past.

They only pay attention to unusual events.

A second goal of this book is to assess the social impact of venture capitalists.

Venture capitalists claim they are making the world a better place.

This is certainly true sometimes.

Impossible Foods is a case in point.

But while video games and social media provide entertainment, information, and allow grandmothers to see their grandchildren from afar, they also foster screen addiction and fake news.

--- p.29~30

The 1957 revolt was made possible by a new form of finance, initially called adventure capital.

This capital was intended to back engineers who were too risky and poor to qualify for conventional bank loans, but whose bold inventions promised the potential for huge returns for investors.

Perhaps the funding of Fairchild Semiconductor, founded by the eight rebels, was the first such venture on the West Coast, and it changed the course of history for the region.

Since Fairchild Semiconductor raised $1.4 million in funding, any team with a big idea and a strong ambition in Silicon Valley has been able to branch out and form a new company, creating the organizational structure that best suits them.

This new capital allowed engineers, inventors, activists, and artistic visionaries to meet, combine, separate, compete, and collaborate.

Sometimes venture capital becomes renegade capital, sometimes it becomes team-building capital, and sometimes it becomes simply experimental capital.

But no matter how you look at it, talents were liberated and a revolution occurred.

--- p.36

It's time for Rock to move on to the next thing.

His company, like the Eight Rebels, made a decent profit of about $700,000, or 600 times its investment.

But I felt that Rock could do better than this.

Although he did close the deal, most of the profits went to Fairchild Camera & Instruments.

Rock tried to protect the eight scientists, but only partially.

But what he did was prove that liberation capital does much more than allow eight rebels to start their own company and continue to work as a team.

Liberated capital was about unleashing human talent.

It was about reinforcing incentives.

It was creating a new kind of applied science and commercial culture.

--- p.68

Valentine made a decision at the end of 1974, a few weeks after visiting the Atari factory.

He decided not to invest right away.

Because Atari was so confusing.

But I wasn't going to let go.

Because Atari's potential was so great.

Instead, we'll approach our relationship with Atari carefully and step by step, starting by rolling up our sleeves and writing the Atari business plan.

After everything went smoothly (Bushnell had bought into his strategy and the business plan had caught the attention of other venture capitalists), Valentine planned to invest.

In other words, he would only invest money if Atari's risks were at least partially eliminated.

So, to support a company with a hot tub culture, we had to combine activism and incrementalism.

--- p.107

Yet, when Apple was raising funds, the stars of the venture capital industry failed to seize the opportunity.

This shows that even the best venture capitalists can make big mistakes.

Tom Perkins and Eugene Kleiner refused to even meet Jobs.

Bill Draper of Sutter Hill Ventures sent an employee to Apple, but was so displeased when he heard reports that Jobs and Wozniak had kept his employee waiting that he lost interest.

Meanwhile, Fitch Johnson, who previously worked with Draper as an SBIC partner, said this:

“How can you have a computer at home? You want to put cookbooks on it?” Jobs kept getting rejected, and then he reached out to Stan Veit, who ran the first computer retail store in faraway New York.

Jobs offered Byte a 10 percent stake in Apple if he invested just $10,000.

Byte recalled with regret:

“I looked at the long-haired hippie youth and his friends and thought,

“If you were the last person left in the world, I could give you $10,000.” Jobs offered Nolan Bushnell, who had hired him at Atari, $50,000 to invest in Apple and get a third of the company.

Bushnell remembers:

“I was so smart that I said, ‘No.’

It's funny when I think about that time.

“When I’m not crying.”

Fortunately for Jobs and Wozniak, by 1976 a large venture capital network had already been established in Silicon Valley, so they didn't have to despair if they were rejected by many.

Soon after, the two found their way to Don Valentine of Sequoia Capital.

--- p.137~138

Before the Yahoo team could reach a conclusion, Son made a second, more radical move.

He asked Moritz and the founders who Yahoo's main competitors were.

They answered like this.

“It’s Excite and Lycos.”

Son Jeong-ui instructed one of his secretaries:

“Take it and write it down.”

Then he said to Moritz and the founders:

“If I don’t invest in Yahoo, I’ll invest in Excite and Lycos and ruin Yahoo.”

For Yang and Philo, and especially for Moritz, Son's threat was a kind of divine revelation.

In the competition to become the most sought-after internet guide, there will be only one winner, and an investor with $100 million to write a check will get to choose who will win.

Like the Don Corleone of the digital world, Son made Moritz an offer he couldn't refuse.

Moritz later resolved never to be in that position again.

--- p.259~260

As summer wore on, Brin and Page rowed back to Door.

They said to the door:

“I have some surprising news for you.

“We have decided to accept your idea.” Now they wanted to bring in a CEO from outside, and they even went so far as to name the person they wanted.

There was only one person who met their standards.

Brin and Page said:

“We want Steve Jobs.”

It was impossible to recruit Jobs.

The door hurried to find an alternative.

He sometimes described himself as “an ordinary scout, contrary to what people say.”

He argued that the nature of venture capital has not changed since the days of Arthur Locke and Tommy Davis.

“We don’t invest based on business plans.

I don't invest based on cash flow.

We invest in people.” Doerr started to network to find executives with computer science backgrounds, but his first choice wasn’t willing to entrust his future to the latest search engine.

Then, in October 2000, Door set his sights on another computer scientist turned executive.

That man was Eric Schmidt, and he was running a software company called Novell.

--- p.305

A day or so later, Levchin met Musk.

Musk said mockingly:

“The reason we decided 6 to 4 is because we were very considerate of you.

As you can see, you made a huge deal.

“An unfair merger like this is nothing short of a windfall for you.”

Levchin turned around with a faint smile and complained to Till on the phone.

“It's all over.

I will not do this kind of deal.

I feel terribly insulted.

“I can’t stand it.” He left the office briskly and walked home.

Harris heard that Levchin had kicked him out.

Harris, who took a position at X.com at Moritz's request, was particularly conscious of shareholders who valued cooperation over competition.

He left the office in a hurry and went to see Levchin.

Levchin took refuge in the apartment's laundry room.

There was an old washing machine there, made by a company with the amusing name of WEB.

This old washing machine requires a quarter to operate.

Harris appealed to Rebchin to reconsider his decision while helping him fold the clothes.

He pleaded with Musk to forget the insult he had recently received with the 6-4 vote.

He and the X.com board only respected Levchin.

In fact, he came with a proposal to appease Levchin, to show that he was sincere.

It was supposed to be 5 vs 5.

Finally, Levchin changed his mind and the merger went ahead.

Musk lost a lot of money by needlessly mocking his opponents.

--- p.333~334

Thiel met Musk, a longtime rival since the PayPal days, by chance at a friend's wedding.

Relations between the two weren't always smooth, given that Thiel's comrades forced Musk out of PayPal.

But Musk was moving on from his bad days at PayPal by investing his share of the profits in two new startups: Tesla, which makes electric cars, and SpaceX, which boasted noble ambitions of drastically reducing the cost of space transportation enough to establish new colonies on Mars.

At the wedding, Musk encouraged Thiel to invest in SpaceX.

Till said this:

“Of course.

“Let’s forget the past.”

--- p.349

It was no surprise that Milner was a huge success.

As he predicted, Facebook's user base and revenue exploded.

By the end of 2010, a year and a half later, Facebook's valuation had reached $50 billion. DST had generated over $1.5 billion in revenue, and Facebook's valuation continued to soar.

In Silicon Valley, this became a watershed moment.

13 years ago, Masayoshi Son surprised traditional venture capitalists by investing $100 million in Yahoo.

In contrast, Milner initially purchased over $300 million worth of Facebook stock.

Meanwhile, Son provided what amounted to bridge financing ahead of Yahoo's stock market debut.

Milner's investment was so substantial that Zuckerberg didn't need to immediately launch an initial public offering. DST's investment met both Facebook's growth capital needs and its employees' liquidity needs.

It was a signal that unlisted technology companies could delay their initial public offerings for about three years.

As a result, private investors were able to create enormous wealth and reap monopolistic profits by leaving the stock market.

Along with this, Milner's investment in Facebook heralds a phase in which entrepreneurs' power will be strengthened more than ever before.

Peter Thiel ran his venture capital firm on Sand Hill Road as a founder-friendly alternative, but Milner took the concept to a whole new level.

He invested in later stages and invested much more money.

It was surprising that he was willing to risk hundreds of millions of dollars while giving up any say in the company.

And while Thiel's respect for founders was based on an understanding of power laws, Milner's was, simply put, based on compromise.

He invested in companies that were qualified to go public in terms of size and sophistication.

So he will act like a stock market investor.

And that too in a passive manner.

--- p.455~456

The apparent success of venture capital-backed companies sometimes raises one question:

Does venture capital create success, or does it simply appear where success already exists? However, as we've already seen, there's research showing that startups supported by venture capital outperform other startups, and this book illustrates numerous instances where venture capital positively impacts portfolio companies.

Even if venture capital's capabilities depend solely on selecting companies to invest in, rather than guiding startups, these capabilities are still valuable.

Making smart choices about which companies to invest in increases the likelihood that the most promising startups will secure the funding they need.

It ensures that society's savings are allocated productively.

--- p.635

Publisher's Review

The creation of Silicon Valley and the redrawing of the global economic map

The surprising and exciting stories of venture capitalists and venture investors.

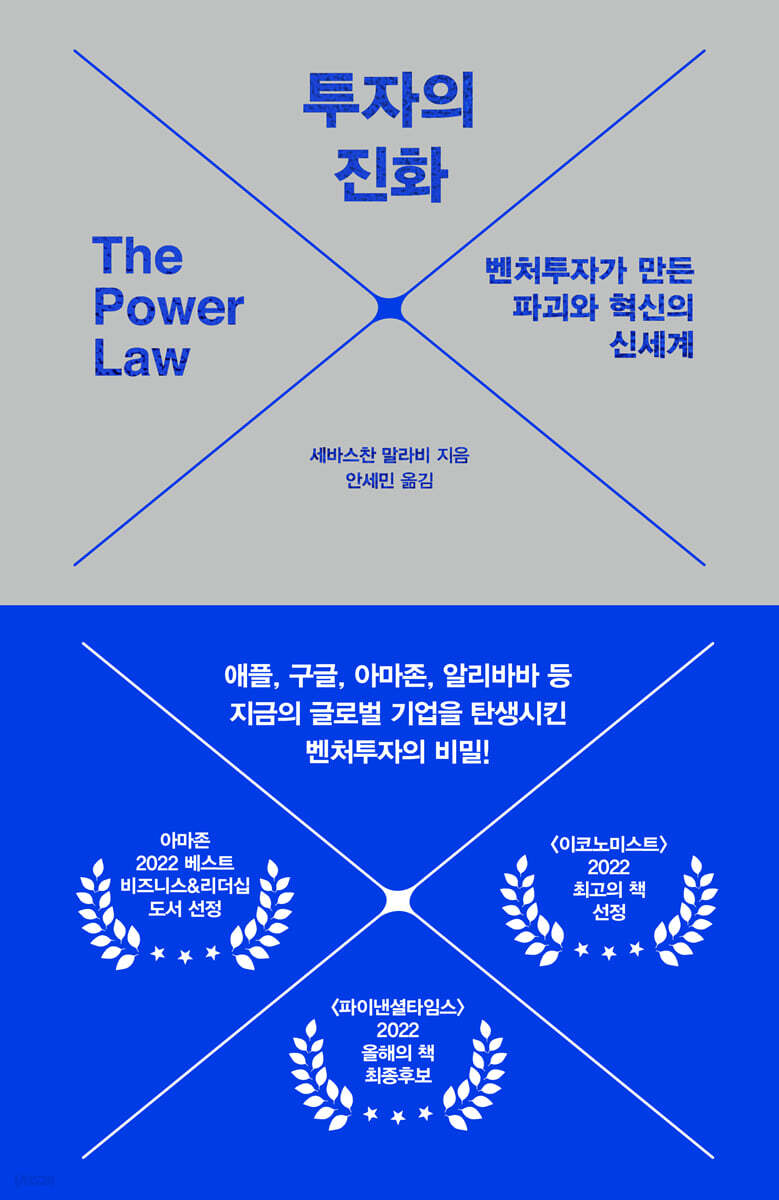

★★★★★ Amazon's Best Business & Leadership Books of 2022

★★★★★ [The Economist] Best Books of 2022

★★★★★ [Financial Times] 2022 Book of the Year Finalist

★★★★★ [TechCrunch] The Best Books Venture Investors Should Read in 2022

Innovations that change the world don't actually come from 'experts'.

Jeff Bezos didn't work in a bookstore before founding Amazon, and Elon Musk didn't work in the automobile industry before founding Tesla.

Venture capitalist Vinod Khosla says, “If I were to start a healthcare company, I wouldn’t hire a healthcare expert as CEO.

Also, if I were to start a manufacturing company, I wouldn't hire a manufacturing expert as CEO.

“I want really smart people who are willing to start from scratch and think outside the box,” he said.

Ultimately, innovation in retail came from Amazon, not Walmart, innovation in media came from Facebook and YouTube, innovation in automobiles came from Tesla, and innovation in the space industry came from SpaceX.

Most attempts by non-expert but intelligent people fail, but a very small number succeed on a scale large enough to offset all others.

Author Sebastian Mallaby refers to this large-scale success as "The Power Law," and argues that it is the essence of venture investing.

Peter Thiel once said, “The greatest secret in venture capital is that the best investment return from a single successful fund equals or exceeds the return of all the other funds.”

Of course, investing in something that is absolutely impossible is a waste.

But investing timidly—into obvious ideas that others can easily copy and ultimately yield little return—is a bigger mistake.

Bold innovators, and the even bolder venture capitalists who invest in them, ultimately changed the future of humanity.

How did Peter Thiel and Elon Musk's success begin?

Was Steve Jobs the CEO Google wanted?

How did Son Jeong-ui swallow Yahoo?

Explore the evolution of investment through the history of venture capital!

We are familiar with the founders and success stories of successful companies like Apple, Google, Facebook, and Alibaba.

But I don't know what the venture capitalists who invested in them were thinking.

This book turns its attention to the beginnings of Silicon Valley and examines the origins of venture investment.

Venture investment began with a rebellion at William Shockley's company, which first brought silicon (semiconductors) to the Valley (West Coast).

Disgusted by Shockley's overbearing leadership, the eight rebels seek another path.

Arthur Rock's funding of these rebels, who were too risky and poor to qualify for conventional bank loans but who promised investors who loved bold inventions the potential for huge returns, was the first venture capital investment in Silicon Valley.

Venture capital has enabled inventors and dreamers to experiment with new possibilities.

Of course, venture capitalists have also had tremendous success.

Arthur Rock, who invested in Fairchild Semiconductor, founded by eight rebels, earned a return of more than 600 times his investment.

However, support from venture capitalists is not limited to funding.

Venture capitalists use their networks to hire executives or help establish partnerships with other companies to ensure the success of the companies they invest in.

Google's Eric Schmidt was also recommended by venture capitalist John Doerr.

Of course, the CEO that Sergey Brin and Larry Page wanted was Steve Jobs.

Confinity, founded by Peter Thiel and Max Levchin, and X.com, founded by Elon Musk, merged with venture capitalists and changed their name to PayPal, ultimately bringing tremendous success to both the founders and venture capitalists.

A venture capitalist who creates the world's best companies through investment!

What draws them to discover businesses,

How to grow and generate huge investment returns?

Uncovering the laws of venture investment: How a small number of successful ventures generate enormous profits!

Venture capitalists don't always succeed.

The power law in investing also shows that there have been countless failures that ultimately did not lead to success.

To minimize investment failures, the best venture capitalists consciously create their own luck.

If success is about meeting an inventor inspired by some unknown magic, then it's better to work systematically to increase the likelihood of this encounter.

While we identify technological trends and anticipate which types of startups will thrive, we also work to overcome cognitive biases through behavioral science.

Sequoia Capital is a venture capital firm that has succeeded through such systematic efforts, investing in Apple, Google, LinkedIn, WhatsApp, and Dropbox.

However, 『The Evolution of Investment』 does not focus solely on the success of venture investment.

The cases of WeWork and Uber, which faced greater risks due to poor investments, show how reckless investments can lead to failure.

Venture investing sometimes seems to involve a huge amount of luck.

But the author says that investors need not only intelligence but also “the vitality to mobilize apathetic entrepreneurs, the patience to endure the inevitable dark days when investments fail, and the emotional intelligence to encourage and guide talented but wayward entrepreneurs.”

So, how can you succeed in investing? "Try and fail.

This is better than not trying.

Above all, remember the logic of the power law.

“The rewards of success will far outweigh the costs of honorable failure.”

The surprising and exciting stories of venture capitalists and venture investors.

★★★★★ Amazon's Best Business & Leadership Books of 2022

★★★★★ [The Economist] Best Books of 2022

★★★★★ [Financial Times] 2022 Book of the Year Finalist

★★★★★ [TechCrunch] The Best Books Venture Investors Should Read in 2022

Innovations that change the world don't actually come from 'experts'.

Jeff Bezos didn't work in a bookstore before founding Amazon, and Elon Musk didn't work in the automobile industry before founding Tesla.

Venture capitalist Vinod Khosla says, “If I were to start a healthcare company, I wouldn’t hire a healthcare expert as CEO.

Also, if I were to start a manufacturing company, I wouldn't hire a manufacturing expert as CEO.

“I want really smart people who are willing to start from scratch and think outside the box,” he said.

Ultimately, innovation in retail came from Amazon, not Walmart, innovation in media came from Facebook and YouTube, innovation in automobiles came from Tesla, and innovation in the space industry came from SpaceX.

Most attempts by non-expert but intelligent people fail, but a very small number succeed on a scale large enough to offset all others.

Author Sebastian Mallaby refers to this large-scale success as "The Power Law," and argues that it is the essence of venture investing.

Peter Thiel once said, “The greatest secret in venture capital is that the best investment return from a single successful fund equals or exceeds the return of all the other funds.”

Of course, investing in something that is absolutely impossible is a waste.

But investing timidly—into obvious ideas that others can easily copy and ultimately yield little return—is a bigger mistake.

Bold innovators, and the even bolder venture capitalists who invest in them, ultimately changed the future of humanity.

How did Peter Thiel and Elon Musk's success begin?

Was Steve Jobs the CEO Google wanted?

How did Son Jeong-ui swallow Yahoo?

Explore the evolution of investment through the history of venture capital!

We are familiar with the founders and success stories of successful companies like Apple, Google, Facebook, and Alibaba.

But I don't know what the venture capitalists who invested in them were thinking.

This book turns its attention to the beginnings of Silicon Valley and examines the origins of venture investment.

Venture investment began with a rebellion at William Shockley's company, which first brought silicon (semiconductors) to the Valley (West Coast).

Disgusted by Shockley's overbearing leadership, the eight rebels seek another path.

Arthur Rock's funding of these rebels, who were too risky and poor to qualify for conventional bank loans but who promised investors who loved bold inventions the potential for huge returns, was the first venture capital investment in Silicon Valley.

Venture capital has enabled inventors and dreamers to experiment with new possibilities.

Of course, venture capitalists have also had tremendous success.

Arthur Rock, who invested in Fairchild Semiconductor, founded by eight rebels, earned a return of more than 600 times his investment.

However, support from venture capitalists is not limited to funding.

Venture capitalists use their networks to hire executives or help establish partnerships with other companies to ensure the success of the companies they invest in.

Google's Eric Schmidt was also recommended by venture capitalist John Doerr.

Of course, the CEO that Sergey Brin and Larry Page wanted was Steve Jobs.

Confinity, founded by Peter Thiel and Max Levchin, and X.com, founded by Elon Musk, merged with venture capitalists and changed their name to PayPal, ultimately bringing tremendous success to both the founders and venture capitalists.

A venture capitalist who creates the world's best companies through investment!

What draws them to discover businesses,

How to grow and generate huge investment returns?

Uncovering the laws of venture investment: How a small number of successful ventures generate enormous profits!

Venture capitalists don't always succeed.

The power law in investing also shows that there have been countless failures that ultimately did not lead to success.

To minimize investment failures, the best venture capitalists consciously create their own luck.

If success is about meeting an inventor inspired by some unknown magic, then it's better to work systematically to increase the likelihood of this encounter.

While we identify technological trends and anticipate which types of startups will thrive, we also work to overcome cognitive biases through behavioral science.

Sequoia Capital is a venture capital firm that has succeeded through such systematic efforts, investing in Apple, Google, LinkedIn, WhatsApp, and Dropbox.

However, 『The Evolution of Investment』 does not focus solely on the success of venture investment.

The cases of WeWork and Uber, which faced greater risks due to poor investments, show how reckless investments can lead to failure.

Venture investing sometimes seems to involve a huge amount of luck.

But the author says that investors need not only intelligence but also “the vitality to mobilize apathetic entrepreneurs, the patience to endure the inevitable dark days when investments fail, and the emotional intelligence to encourage and guide talented but wayward entrepreneurs.”

So, how can you succeed in investing? "Try and fail.

This is better than not trying.

Above all, remember the logic of the power law.

“The rewards of success will far outweigh the costs of honorable failure.”

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: November 1, 2023

- Format: Hardcover book binding method guide

- Page count, weight, size: 772 pages | 1,168g | 145*225*41mm

- ISBN13: 9791168127807

- ISBN10: 1168127807

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)