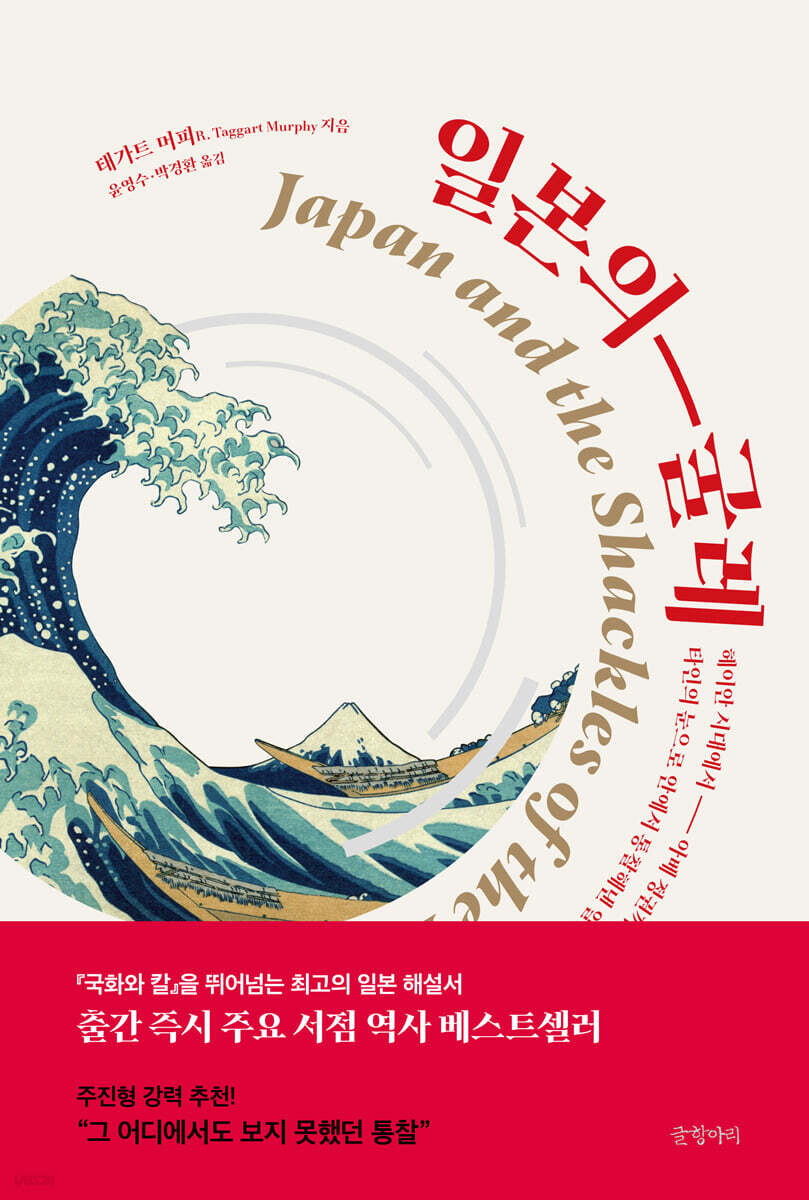

Japanese shackles

|

Description

Book Introduction

- A word from MD

-

Understanding Japan as a Problematic CountryJapan is a country that foreigners may find difficult to understand: a friendly people, a right-wing government, a strict patriarchal system, a peculiar sexual culture, and an imperial system.

Taggart Murphy, who has lived in Japan for over 40 years, wrote "The Shackles of Japan" and analyzed this aspect of Japan with a cool head.

March 5, 2021. History PD Son Min-gyu

There is probably no country today that causes more fatigue to our people than Japan.

Although the intense emotions have somewhat subsided since the “No Japan” movement of 2019, antipathy toward Japan is now higher than ever.

There is no guarantee that this atmosphere will improve any time soon.

Although the worst Abe administration has stepped down, the Suga administration has taken over as an extension of it, and the overall right-wing atmosphere in Japanese society, denial of past history, attacks on Korea on the international stage, and subtle disregard for Korea are creating a cycle of hostility.

We are also not at all forward-looking toward Japan.

I think I know Japan well, but can I really say I know it well beyond a cultural approach that focuses on interest?

In short, the two countries do not recognize each other, do not even try to get to know each other seriously, and are stuck in a state of superficial and hostile finger-pointing at each other.

What attitude should publishing take in such a situation?

Should we fan that animosity, or should we ignore the festering situation and focus solely on cultural and practical exchanges?

The recently published 『Japan's Shackles』 is based on the complex psychology of trying to resolve a frustrating situation where one cannot do anything.

Here is a thick humanities book called "The Japanese Shackles" written by an American named Taggart Murphy.

The subtitle is unique.

The phrase “the light and shadow of Japan as seen from within through the eyes of others” best captures the identity of this book.

The author of this book is an American expert in international politics and economics, and a Japan expert who has lived in Japan for over 40 years since first setting foot on Japanese soil at the age of 15.

As a Westerner, he is immersed in the unfamiliar, alien, and superficially incomprehensible aspects of Japan, but soon distances himself from it, gradually grasping the contradictory aspects of this society as both an insider and an outsider.

In his opinion, Japanese people were strange.

He was often humbled by his kind service, often remained silent when something worth complaining about, and routinely displayed a resigned attitude that rarely challenged power.

On the other hand, their sex industry has blossomed in ways that Westerners find difficult to imagine.

Also, Japanese people find pleasure in small things.

The most unique aspect of the Japanese is that they do not consider contradictions to be contradictions.

The more the author likes Japan, the more he realizes that there is a certain tragic element attached to their lives.

Much of Japan's modern history is tragic, and this book provides insight into the fact that these tragedies originated from "something" within the Japanese people rather than from a combination of internal and external factors.

“I’ve thought countless times about how great it would have been if I had read this book when I first came to Japan.

This book contains literally everything Mr. Taggart has seen and learned about Japan during his lifetime living there.

Beginning with the founding of Nara and Kyoto, the turmoil of the Warring States period, the fabric of Edo society, the isolationist policy and the Meiji Restoration, the madness of World War II, the postwar economic miracle and salaryman culture, the formation and collapse of the bubble economy of the 1980s, and the recent Abe administration, the author presents the author's comprehensive insight into Japanese society, crossing over history, economy, politics, and culture.

The translators, who have worked and lived in Japan for a long time, translated this book with the conviction that “there is no better book for understanding Japan.”

This is because it is not common to find a book that connects Japan's politics, economy, and culture in a clear and concise manner over the long course of history, offering comprehensive knowledge and insight.

Although the intense emotions have somewhat subsided since the “No Japan” movement of 2019, antipathy toward Japan is now higher than ever.

There is no guarantee that this atmosphere will improve any time soon.

Although the worst Abe administration has stepped down, the Suga administration has taken over as an extension of it, and the overall right-wing atmosphere in Japanese society, denial of past history, attacks on Korea on the international stage, and subtle disregard for Korea are creating a cycle of hostility.

We are also not at all forward-looking toward Japan.

I think I know Japan well, but can I really say I know it well beyond a cultural approach that focuses on interest?

In short, the two countries do not recognize each other, do not even try to get to know each other seriously, and are stuck in a state of superficial and hostile finger-pointing at each other.

What attitude should publishing take in such a situation?

Should we fan that animosity, or should we ignore the festering situation and focus solely on cultural and practical exchanges?

The recently published 『Japan's Shackles』 is based on the complex psychology of trying to resolve a frustrating situation where one cannot do anything.

Here is a thick humanities book called "The Japanese Shackles" written by an American named Taggart Murphy.

The subtitle is unique.

The phrase “the light and shadow of Japan as seen from within through the eyes of others” best captures the identity of this book.

The author of this book is an American expert in international politics and economics, and a Japan expert who has lived in Japan for over 40 years since first setting foot on Japanese soil at the age of 15.

As a Westerner, he is immersed in the unfamiliar, alien, and superficially incomprehensible aspects of Japan, but soon distances himself from it, gradually grasping the contradictory aspects of this society as both an insider and an outsider.

In his opinion, Japanese people were strange.

He was often humbled by his kind service, often remained silent when something worth complaining about, and routinely displayed a resigned attitude that rarely challenged power.

On the other hand, their sex industry has blossomed in ways that Westerners find difficult to imagine.

Also, Japanese people find pleasure in small things.

The most unique aspect of the Japanese is that they do not consider contradictions to be contradictions.

The more the author likes Japan, the more he realizes that there is a certain tragic element attached to their lives.

Much of Japan's modern history is tragic, and this book provides insight into the fact that these tragedies originated from "something" within the Japanese people rather than from a combination of internal and external factors.

“I’ve thought countless times about how great it would have been if I had read this book when I first came to Japan.

This book contains literally everything Mr. Taggart has seen and learned about Japan during his lifetime living there.

Beginning with the founding of Nara and Kyoto, the turmoil of the Warring States period, the fabric of Edo society, the isolationist policy and the Meiji Restoration, the madness of World War II, the postwar economic miracle and salaryman culture, the formation and collapse of the bubble economy of the 1980s, and the recent Abe administration, the author presents the author's comprehensive insight into Japanese society, crossing over history, economy, politics, and culture.

The translators, who have worked and lived in Japan for a long time, translated this book with the conviction that “there is no better book for understanding Japan.”

This is because it is not common to find a book that connects Japan's politics, economy, and culture in a clear and concise manner over the long course of history, offering comprehensive knowledge and insight.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

Recommended Preface

Introduction

introduction

Part 1: The Origin of the Shackles

Chapter 1 Japan before the Edo period

The Imperial System | The Fujiwara Family and the Establishment of Heian-kyo | The Legacy of the Heian Period | Literature Written by Women | The Makura no Soshi and The Tale of Genji | The Collapse of the Heian Order and the Rise of Feudalism | The Shogun | The Mongol Invasion, the Fall of Kamakura, and the Ashikaga Shogunate | Japanese Feudalism | Culture and Religion in the Feudal Era | The Arrival of Europeans | The Reunification of Japan

Chapter 2: The Birth of Japan as a Modern Nation

The Tokugawa Period's Isolation | The Tokugawa Shogunate's Obsession with Order and Stability | Economic and Social Change | Popular Culture | The Story of the 47 Ronin | Commodore Perry's "Black Ships" and the Fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate | The "Revolution" of 1868? | The End of the Shogunate

Chapter 3: From the Meiji Restoration to the US Military Government

Iwasaki Yataro and the Birth of Modern Japanese Industrial Organization | The Accumulation of Capital and the Appearance of a Constitutional Government | The First Sino-Japanese War of 1895 | The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 | The Tragedy of Modern Japan Rooted in the Meiji Era | Natsume Soseki's "Kokoro" and the Legacy of Meiji | Yamagata Aritomo and the Bureaucracy that Overcame Political Control | The Disasters of War | The Marco Polo Bridge Incident and the Battle of Nomonhan | Pearl Harbor, Surrender, and the Legacy of War

Chapter 4: The Economic Miracle

The Unusual Circumstances of the Postwar Decade | The Political and Cultural Foundations of High Growth

Chapter 5: Institutional Framework for High Growth

Japanese corporations | Industry associations and competition control | Employment practices | Education system | Financial system | Bureaucracy | 'Management of reality'

Chapter 6: What We Gained and Lost Through Growth

The Price of Growth | Baseball and the Emergence of Salaried Worker Culture | Women in Japan during the High-Growth Era | Seiko Matsuda | The Institutions of High-Growth and the Global Economic Framework

Part 2: The Shackles of Yesterday That Bind Today's Japan

Chapter 7: Economy and Finance

Balance Sheet Depression | The Japan Difference | Avoiding Panic: Rescuing Japan's Financial Institutions | Faulty Assumptions and the Wide Open Door to a Fiscal Deficit | The Origins of the Asian Financial Crisis | The Japanese Government's Fiscal Spending

Chapter 8 Business

The Service Sector | Changing Employment Practices | The Challenges of Globalization | Global Brands and Foreign Direct Investment | Abandoning Sunk Costs | Challenges from Korea | The Future of Japanese Business and the Global Crisis of Capitalism

Chapter 9 Socio-cultural Change

Japanese Culture Spreads Globally | Gyaru | Obatarian, Sodai Gomi, and Twilight Divorce | Herbivorous Men | Japanese Masculinity | The Changing Landscape of Japanese Men | The Rise of Class | The Decline of Japan's Leadership

Chapter 10 Politics

The 1955 System | Kakuei Tanaka | The Nixon Shock and Tanaka's Prime Ministership | The Lockheed Scandal | Shogun Tanaka | Close Entourage: Noboru Takeshita and Shin Kanemaru | Ichiro Ozawa | Guardians of Political Order | The 1994 Electoral Reform | Junichiro Koizumi | Yasukuni Shrine and the Koizumi Administration's Foreign Relations | The Liberal Democratic Party after Koizumi

Chapter 11 Japan and the World

'New Japan Experts' | Okinawa and the Futenma Marine Base | The Collapse of the Hatoyama Administration | 'Agents of Influence' | The Fate of the Naoto Kan Administration on March 11th | The Self-Destruction of the Noda Administration | The Senkaku Islands and Japan's Territorial Dispute | The Return of Shinzo Abe | Economic Recovery? | The Trans-Pacific Partnership, the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets Act, and the Abe Administration's Priorities | Establishing Relations with China | The Unsustainable US-Japan 'Alliance' | Returning to Asia | Abe's Excessive Greed and the Future

Appendix 1: Meiji Leaders

Appendix 2: Powerful Politicians and Bureaucrats in Postwar Japan

Further Reading

Author's Note on the Korean Edition

Translator's Note

Introduction

introduction

Part 1: The Origin of the Shackles

Chapter 1 Japan before the Edo period

The Imperial System | The Fujiwara Family and the Establishment of Heian-kyo | The Legacy of the Heian Period | Literature Written by Women | The Makura no Soshi and The Tale of Genji | The Collapse of the Heian Order and the Rise of Feudalism | The Shogun | The Mongol Invasion, the Fall of Kamakura, and the Ashikaga Shogunate | Japanese Feudalism | Culture and Religion in the Feudal Era | The Arrival of Europeans | The Reunification of Japan

Chapter 2: The Birth of Japan as a Modern Nation

The Tokugawa Period's Isolation | The Tokugawa Shogunate's Obsession with Order and Stability | Economic and Social Change | Popular Culture | The Story of the 47 Ronin | Commodore Perry's "Black Ships" and the Fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate | The "Revolution" of 1868? | The End of the Shogunate

Chapter 3: From the Meiji Restoration to the US Military Government

Iwasaki Yataro and the Birth of Modern Japanese Industrial Organization | The Accumulation of Capital and the Appearance of a Constitutional Government | The First Sino-Japanese War of 1895 | The Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 | The Tragedy of Modern Japan Rooted in the Meiji Era | Natsume Soseki's "Kokoro" and the Legacy of Meiji | Yamagata Aritomo and the Bureaucracy that Overcame Political Control | The Disasters of War | The Marco Polo Bridge Incident and the Battle of Nomonhan | Pearl Harbor, Surrender, and the Legacy of War

Chapter 4: The Economic Miracle

The Unusual Circumstances of the Postwar Decade | The Political and Cultural Foundations of High Growth

Chapter 5: Institutional Framework for High Growth

Japanese corporations | Industry associations and competition control | Employment practices | Education system | Financial system | Bureaucracy | 'Management of reality'

Chapter 6: What We Gained and Lost Through Growth

The Price of Growth | Baseball and the Emergence of Salaried Worker Culture | Women in Japan during the High-Growth Era | Seiko Matsuda | The Institutions of High-Growth and the Global Economic Framework

Part 2: The Shackles of Yesterday That Bind Today's Japan

Chapter 7: Economy and Finance

Balance Sheet Depression | The Japan Difference | Avoiding Panic: Rescuing Japan's Financial Institutions | Faulty Assumptions and the Wide Open Door to a Fiscal Deficit | The Origins of the Asian Financial Crisis | The Japanese Government's Fiscal Spending

Chapter 8 Business

The Service Sector | Changing Employment Practices | The Challenges of Globalization | Global Brands and Foreign Direct Investment | Abandoning Sunk Costs | Challenges from Korea | The Future of Japanese Business and the Global Crisis of Capitalism

Chapter 9 Socio-cultural Change

Japanese Culture Spreads Globally | Gyaru | Obatarian, Sodai Gomi, and Twilight Divorce | Herbivorous Men | Japanese Masculinity | The Changing Landscape of Japanese Men | The Rise of Class | The Decline of Japan's Leadership

Chapter 10 Politics

The 1955 System | Kakuei Tanaka | The Nixon Shock and Tanaka's Prime Ministership | The Lockheed Scandal | Shogun Tanaka | Close Entourage: Noboru Takeshita and Shin Kanemaru | Ichiro Ozawa | Guardians of Political Order | The 1994 Electoral Reform | Junichiro Koizumi | Yasukuni Shrine and the Koizumi Administration's Foreign Relations | The Liberal Democratic Party after Koizumi

Chapter 11 Japan and the World

'New Japan Experts' | Okinawa and the Futenma Marine Base | The Collapse of the Hatoyama Administration | 'Agents of Influence' | The Fate of the Naoto Kan Administration on March 11th | The Self-Destruction of the Noda Administration | The Senkaku Islands and Japan's Territorial Dispute | The Return of Shinzo Abe | Economic Recovery? | The Trans-Pacific Partnership, the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets Act, and the Abe Administration's Priorities | Establishing Relations with China | The Unsustainable US-Japan 'Alliance' | Returning to Asia | Abe's Excessive Greed and the Future

Appendix 1: Meiji Leaders

Appendix 2: Powerful Politicians and Bureaucrats in Postwar Japan

Further Reading

Author's Note on the Korean Edition

Translator's Note

Into the book

Instead, as with true love, the fascination was overlaid with a realization of tragedy.

It is a realization that loving imperfect creatures and what they create comes at a price.

Because now I know something I didn't know before.

Much of Japan's modern history is tragic, and as is often the case, it stems not from a combination of external factors and internal flaws, but from that very "something" that made me love this country and its people.

--- p.30~31

What drew them all together was sex.

Sex was the overt root and driving force behind the splendidly flourishing popular culture of the Edo period.

Later, as the Japanese began to pay attention to Western moral standards, the roots of authentic Japanese art forms such as Kabuki and Ukiyo-e were deliberately hidden.

This was especially true when Westerners began to become enthusiastic about woodblock prints and other works of art, which had until then been treated as trash by Japan's ruling class.

--- p.104

The idea that a young man would willingly cut open his own stomach to avenge an insult to his sovereign struck most peasants as bizarre and unfilial.

A young man must work hard until he collapses and be a son to continue the family line and be filial to his father.

The samurai spirit itself had already become so fossilized during the Edo period that it became a target of satire.

The samurai, as if protesting against a society in which such a spirit had become practically meaningless, fell into more exaggerated self-sacrifice and extreme asceticism.

But when Japan suddenly faced a military threat from outside and an intensifying civil rights movement at home, the values of the samurai were taken out of the Edo-period museum and repackaged as values needed not just for a modernized military but for a militaristic society as a whole.

--- p.140

The fate of religion during the Meiji period mirrors in many ways the path Japan followed thereafter.

By branding it as "un-Japanese," they destroyed the existing order, and by creating what were essentially new religions, they packaged them as "pure" and indigenous traditions, while at the same time, a small elite enthusiastic about Western civilization left its institutional legacy in Japan for a long time.

Furthermore, Meiji Japan, obsessed with clarifying the meaning of "Japaneseness," tried hard to erase the influence of mainland China, which could be said to be essential for understanding the true nature of Japan.

At the same time, we hastily accepted a lot of Western culture and immaturely digested it.

The result was a kind of schizophrenia with regard to other Asian countries and the West, a contradiction that would later lead to disastrous political consequences.

--- p.144

Regardless of how the spirit of Japanese business manifests itself in the future, it's best not to hold out high hopes that Japanese companies will regain the vitality they once possessed through various reforms.

The extraordinary decades in which Japan's limited liability companies achieved truly miraculous feats will not be repeated.

Because the problems of Japanese companies cannot be considered separately from the broader challenges facing Japan as a nation adrift both culturally and politically.

To gauge the future of Japanese business, we must consider not only global geopolitical and economic factors, but also the future of the culture and politics within which Japanese business operates.

It is a realization that loving imperfect creatures and what they create comes at a price.

Because now I know something I didn't know before.

Much of Japan's modern history is tragic, and as is often the case, it stems not from a combination of external factors and internal flaws, but from that very "something" that made me love this country and its people.

--- p.30~31

What drew them all together was sex.

Sex was the overt root and driving force behind the splendidly flourishing popular culture of the Edo period.

Later, as the Japanese began to pay attention to Western moral standards, the roots of authentic Japanese art forms such as Kabuki and Ukiyo-e were deliberately hidden.

This was especially true when Westerners began to become enthusiastic about woodblock prints and other works of art, which had until then been treated as trash by Japan's ruling class.

--- p.104

The idea that a young man would willingly cut open his own stomach to avenge an insult to his sovereign struck most peasants as bizarre and unfilial.

A young man must work hard until he collapses and be a son to continue the family line and be filial to his father.

The samurai spirit itself had already become so fossilized during the Edo period that it became a target of satire.

The samurai, as if protesting against a society in which such a spirit had become practically meaningless, fell into more exaggerated self-sacrifice and extreme asceticism.

But when Japan suddenly faced a military threat from outside and an intensifying civil rights movement at home, the values of the samurai were taken out of the Edo-period museum and repackaged as values needed not just for a modernized military but for a militaristic society as a whole.

--- p.140

The fate of religion during the Meiji period mirrors in many ways the path Japan followed thereafter.

By branding it as "un-Japanese," they destroyed the existing order, and by creating what were essentially new religions, they packaged them as "pure" and indigenous traditions, while at the same time, a small elite enthusiastic about Western civilization left its institutional legacy in Japan for a long time.

Furthermore, Meiji Japan, obsessed with clarifying the meaning of "Japaneseness," tried hard to erase the influence of mainland China, which could be said to be essential for understanding the true nature of Japan.

At the same time, we hastily accepted a lot of Western culture and immaturely digested it.

The result was a kind of schizophrenia with regard to other Asian countries and the West, a contradiction that would later lead to disastrous political consequences.

--- p.144

Regardless of how the spirit of Japanese business manifests itself in the future, it's best not to hold out high hopes that Japanese companies will regain the vitality they once possessed through various reforms.

The extraordinary decades in which Japan's limited liability companies achieved truly miraculous feats will not be repeated.

Because the problems of Japanese companies cannot be considered separately from the broader challenges facing Japan as a nation adrift both culturally and politically.

To gauge the future of Japanese business, we must consider not only global geopolitical and economic factors, but also the future of the culture and politics within which Japanese business operates.

--- p.365

Publisher's Review

A complex country like Japan

Amazing insights that are transparently revealed

“The most important book about Japan by a foreign author in the past 20 years!”

Combining thoughts on Japanese politics and economics with history and culture

When he received the offer from Oxford University Press, Professor Taggart Murphy decided to “combine Japanese politics and economics with history and culture in a way that no other kind of writing could do.”

Although it is not widely known, the author's basic position is that "it is difficult to understand Japan by separating each issue," considering the central role that Japan's creation of credit and credit unions has played in shaping the framework of today's global financial markets.

It is difficult to understand any aspect of Japanese reality without addressing the sum total of the Japanese experience.

In other words, the Bank of Japan's monetary policy, the personnel practices of Japanese companies, Tokyo's bizarre street fashions, the endless game of musical chairs in Japanese politics, and Japan's centuries of isolation—these issues are all interconnected in some way.

The author, whose thoughts had reached this point, said, “It would give me the opportunity to organize the themes that had captivated me since I was fifteen, when I got off at the old, bustling Haneda Airport, took a long-distance bus, and saw the gray, vibrant cityscape I had never seen before, and to bring order to my lifelong thoughts.

“That’s how I decided to write a book,” he says.

"Japan's Shackles" covers Japan's politics, economy, society, culture, and history.

As I mentioned in the preface to the book, it combines Professor Murphy's thoughts on Japanese politics and economics with his thoughts on history and culture.

The author's multifaceted analysis of Japanese society, combining an outsider's perspective with an insider's understanding, offers insights unparalleled elsewhere.

A country brimming with responsibility, a country running at the height of irresponsibility

Most Japanese people take their responsibilities very seriously.

In the West, they say that if something is worth doing, you should do it well.

In Japan, even if something isn't worth doing (and everyone knows it isn't), you have to do it well.

The level of courtesy and service I encounter in Japan, even in the most menial or, indeed, grimy tasks, is so high that it's almost impossible to imagine anywhere else, to the point where I sometimes find myself fantasizing that the world exists solely for my pleasure.

If you do even a little bit of something, you will hear a cry of "Otsukaresama deshita! Thank you for your hard work!" (a tone of exaggerated gratitude that says "Thank you for your great sacrifice").

If you treat someone to a cup of tea and dessert, you will be thanked for treating them to a sumptuous feast (gochisosama deshita).

On the other hand, if you are invited to a grand dinner, you will be greeted with an embarrassing greeting because the food is not very well prepared.

Of course, all this is a formality.

But even if this is a formality and everyone knows it, we must act as if the formality is filled with spontaneous emotions.

Because everyone is acting in accordance with such expectations, and because it is an open secret, perhaps the most empty and formal acts actually take on meaning.

This formality also applies to interpersonal relationships.

Even if you're working a boring job dealing with difficult, lousy clients who don't particularly like you or who have no intention of rewarding you financially for your efforts, treat them as if they were your best friend or passionate colleague.

But when you act as if you genuinely care about the well-being of others, as if you have the best colleagues, as if your most important job is to meet the needs of whoever the customer is, you actually internalize feelings like affection, respect, and a will to do the best job you can.

Before I know it, I am surrounded by people I care deeply about, and I feel like they care about me too.

It's easy to see that there are tremendous advantages to a society where everyone can be reassured that they will do what they promise, and that they will do it well.

What is often overlooked is that this attitude of trying to deny contradictions while believing that everything is going well when in reality it is not, has a fatal political dimension.

That attitude may be what makes Japan so attractive and successful.

But this also explains the tragedy of modern Japanese history.

Because it creates an ideal environment for exploiting the public.

It's not just a matter of the public internalizing the attitude of accepting everything as it is, which they consider maturity, and finding meaning in life by pursuing goals they know are perhaps worthless.

When the influence of these fluid values, deeply ingrained in Japan, reaches the level of society's leaders, it causes those in power to engage in double-think, deluding themselves about what they do and their motivations.

The Japanese people's victim mentality and habit of resignation

Japan is no longer a country that poses a threat enough to turn its own country and its neighbors into a sea of fire.

However, the awareness that we live in a world where various things happen for reasons that are neither clear nor explainable, and that individuals have no choice but to do their best to adapt and fulfill their own duties, still prevails.

The Japanese have a word for this ritual.

This is the victim consciousness (higaisha ishiki).

There are many situations in which victim consciousness can lead to real-world consequences, including:

For example, Japan, in order to solve its dire fiscal dilemma, has abandoned the social norms that once ensured near-universal economic stability for its entire population.

They also raised taxes and prices, destroying household purchasing power and breaking promises that the national pension system was supposed to keep.

The world of corporations guaranteeing a quality of life for their employees has been replaced by a world of low-income contract workers with no security or future.

Those who pursue these policies don't snicker at the thought of what they've done, like the Wall Street bankers who destroy corporate assets and lay off employees.

Instead, they bow their heads with gloomy faces, thinking that they too have no choice but to join the ranks of sacrifice.

It doesn't matter if they gain personal benefit through that sacrifice.

Because millions of Japanese people will just shrug their shoulders, sigh, and say, “Shikaga nai (I can’t do it).”

The fact that there are other alternatives (strong unions, a healthy political party representing workers, a robust social safety net, and various policies to boost real household income and stimulate domestic demand to revive Japanese industry) is not taken into account.

Even if it is considered, it is criticized as immature populism.

Even if such an alternative were somehow initiated, it would be attacked as "un-Japanese" and belittled by a system that has evolved to silence those who threaten the establishment.

In the book, the author examines some of these systems from the Heian period through Edo and into modern times.

The last two chapters, in particular, deal with how the forces that could have offered a better alternative to Japan's dilemma in recent decades were destroyed by direct American complicity and intervention.

The author emphasizes that we must begin by understanding how organizations like corporations, banks, governments, the military, and police, whose purpose is to provide citizens with a decent and safe life, have been corrupted and controlled by those who exploit them to fill their own pockets and those who attempt to control and monitor the entire population under the pretext of protecting the nation from imaginary threats.

These people require a peculiar psychological state of doing what is necessary to run an organization in this way, while hiding their real motivations from themselves. George Orwell famously gave this ideological acrobatics the name "doublethink."

Those in power in Japan were accustomed to a political and cultural tradition in which tolerance of contradiction was not only permitted but essential.

The Origins of Japan's Political Structure: The Shackles of the 100 Years Since Meiji

This book basically deals with Japanese history.

Among these, it is worth recalling that the Edo period maintained peace for hundreds of years based on the strong authority of the shogunate, and achieved remarkable socioeconomic development beyond imagination.

The accumulation of wealth was centered around the merchants at the very bottom, but the enormous contradictory energy that arose from the tenacious and thorough maintenance of the class system dominated by the samurai is still useful in explaining various phenomena in Japanese society today.

This analysis is brilliant, showing how the compressed efforts of just one generation after the Meiji Restoration to break away from Asia and join the ranks of Western powers transformed the Japanese mentality and how it still serves as a shackle to Japan's future.

And the analysis that while the Meiji Restoration put forward the two "fictions" of the imperial system and the parliamentary system, in reality the main players of the Restoration practiced oligarchic politics behind the scenes, and that the large power vacuum left by their deaths in old age gave birth to the current structure of Japanese politics, which is swayed by bureaucrats without ultimate responsibility, and that the reason fundamental reform in Japan's organization is so difficult is precisely because of this culture without a place for ultimate responsibility is also insightful.

As a scholar of international political economy, the author also devotes a significant portion of the book to discussions of politics and economics after World War II.

The author clearly differs from the "new Japan experts" in the United States who act to protect the existing US-Japan relationship.

As the title suggests, the book not only criticizes Japan's chronic problems, but also unhesitatingly criticizes the United States, which bears the original sin for Japan's current problems.

The fact that the US military government was largely responsible for the difficulty of reconciling Japan's past by blocking the opportunity for the Japanese people to reflect on their own mistakes during the post-war process is something that Americans should hear with pain.

The issue of the Futenma naval base in Okinawa, which has been a hot potato in U.S.-Japan relations since the 1990s, has also been criticized for being unnecessarily prolonged and complicated due to competition and selfishness among U.S. bureaucracies.

Discussions about exchange rate policy and bubbles delve into considerable depth, allowing you to grasp the dramatic trajectory of the Japanese economy.

One of the important themes covered in this book is that after Japan's defeat in the war, it entrusted its national defense and foreign affairs to the United States, and instead used the United States as leverage to develop its economy. Later, the United States, in turn, relied on Japan's economic power to maintain a dollar-centered global economy.

The more I read this book, the more I am surprised by how many aspects of Korean society resemble those of post-war Japan.

Even though our country's economic growth model is inevitably similar to that of Japan, there are many sentences that would not be awkward at all if only the subject were changed from Japan to Korea.

Korea, which had been following Japan in this way, has gradually changed its trajectory since the late 20th century. However, I think that is why the same issues that Japan is struggling with - chronic low growth, media independence, judicial reform, and a low birth rate and aging society - are also homework for us.

An insightful analysis of what ails Japan.

- [The Economist]

"The Shackles of Japan" is an excellent and immersive introduction to Japan.

Analysis of Japanese politics and economics is also full of intellectual stimulation.

There are many lessons to be learned not only for Japan, but also for the United States and other countries.

- [Complete Review]

Murphy concretely demonstrates how Japan is dependent on the United States to maintain its existing political system and future.

The final part of the book provides an in-depth analysis of the Abe administration.

- [Publisher's Weekly]

Amazing insights that are transparently revealed

“The most important book about Japan by a foreign author in the past 20 years!”

Combining thoughts on Japanese politics and economics with history and culture

When he received the offer from Oxford University Press, Professor Taggart Murphy decided to “combine Japanese politics and economics with history and culture in a way that no other kind of writing could do.”

Although it is not widely known, the author's basic position is that "it is difficult to understand Japan by separating each issue," considering the central role that Japan's creation of credit and credit unions has played in shaping the framework of today's global financial markets.

It is difficult to understand any aspect of Japanese reality without addressing the sum total of the Japanese experience.

In other words, the Bank of Japan's monetary policy, the personnel practices of Japanese companies, Tokyo's bizarre street fashions, the endless game of musical chairs in Japanese politics, and Japan's centuries of isolation—these issues are all interconnected in some way.

The author, whose thoughts had reached this point, said, “It would give me the opportunity to organize the themes that had captivated me since I was fifteen, when I got off at the old, bustling Haneda Airport, took a long-distance bus, and saw the gray, vibrant cityscape I had never seen before, and to bring order to my lifelong thoughts.

“That’s how I decided to write a book,” he says.

"Japan's Shackles" covers Japan's politics, economy, society, culture, and history.

As I mentioned in the preface to the book, it combines Professor Murphy's thoughts on Japanese politics and economics with his thoughts on history and culture.

The author's multifaceted analysis of Japanese society, combining an outsider's perspective with an insider's understanding, offers insights unparalleled elsewhere.

A country brimming with responsibility, a country running at the height of irresponsibility

Most Japanese people take their responsibilities very seriously.

In the West, they say that if something is worth doing, you should do it well.

In Japan, even if something isn't worth doing (and everyone knows it isn't), you have to do it well.

The level of courtesy and service I encounter in Japan, even in the most menial or, indeed, grimy tasks, is so high that it's almost impossible to imagine anywhere else, to the point where I sometimes find myself fantasizing that the world exists solely for my pleasure.

If you do even a little bit of something, you will hear a cry of "Otsukaresama deshita! Thank you for your hard work!" (a tone of exaggerated gratitude that says "Thank you for your great sacrifice").

If you treat someone to a cup of tea and dessert, you will be thanked for treating them to a sumptuous feast (gochisosama deshita).

On the other hand, if you are invited to a grand dinner, you will be greeted with an embarrassing greeting because the food is not very well prepared.

Of course, all this is a formality.

But even if this is a formality and everyone knows it, we must act as if the formality is filled with spontaneous emotions.

Because everyone is acting in accordance with such expectations, and because it is an open secret, perhaps the most empty and formal acts actually take on meaning.

This formality also applies to interpersonal relationships.

Even if you're working a boring job dealing with difficult, lousy clients who don't particularly like you or who have no intention of rewarding you financially for your efforts, treat them as if they were your best friend or passionate colleague.

But when you act as if you genuinely care about the well-being of others, as if you have the best colleagues, as if your most important job is to meet the needs of whoever the customer is, you actually internalize feelings like affection, respect, and a will to do the best job you can.

Before I know it, I am surrounded by people I care deeply about, and I feel like they care about me too.

It's easy to see that there are tremendous advantages to a society where everyone can be reassured that they will do what they promise, and that they will do it well.

What is often overlooked is that this attitude of trying to deny contradictions while believing that everything is going well when in reality it is not, has a fatal political dimension.

That attitude may be what makes Japan so attractive and successful.

But this also explains the tragedy of modern Japanese history.

Because it creates an ideal environment for exploiting the public.

It's not just a matter of the public internalizing the attitude of accepting everything as it is, which they consider maturity, and finding meaning in life by pursuing goals they know are perhaps worthless.

When the influence of these fluid values, deeply ingrained in Japan, reaches the level of society's leaders, it causes those in power to engage in double-think, deluding themselves about what they do and their motivations.

The Japanese people's victim mentality and habit of resignation

Japan is no longer a country that poses a threat enough to turn its own country and its neighbors into a sea of fire.

However, the awareness that we live in a world where various things happen for reasons that are neither clear nor explainable, and that individuals have no choice but to do their best to adapt and fulfill their own duties, still prevails.

The Japanese have a word for this ritual.

This is the victim consciousness (higaisha ishiki).

There are many situations in which victim consciousness can lead to real-world consequences, including:

For example, Japan, in order to solve its dire fiscal dilemma, has abandoned the social norms that once ensured near-universal economic stability for its entire population.

They also raised taxes and prices, destroying household purchasing power and breaking promises that the national pension system was supposed to keep.

The world of corporations guaranteeing a quality of life for their employees has been replaced by a world of low-income contract workers with no security or future.

Those who pursue these policies don't snicker at the thought of what they've done, like the Wall Street bankers who destroy corporate assets and lay off employees.

Instead, they bow their heads with gloomy faces, thinking that they too have no choice but to join the ranks of sacrifice.

It doesn't matter if they gain personal benefit through that sacrifice.

Because millions of Japanese people will just shrug their shoulders, sigh, and say, “Shikaga nai (I can’t do it).”

The fact that there are other alternatives (strong unions, a healthy political party representing workers, a robust social safety net, and various policies to boost real household income and stimulate domestic demand to revive Japanese industry) is not taken into account.

Even if it is considered, it is criticized as immature populism.

Even if such an alternative were somehow initiated, it would be attacked as "un-Japanese" and belittled by a system that has evolved to silence those who threaten the establishment.

In the book, the author examines some of these systems from the Heian period through Edo and into modern times.

The last two chapters, in particular, deal with how the forces that could have offered a better alternative to Japan's dilemma in recent decades were destroyed by direct American complicity and intervention.

The author emphasizes that we must begin by understanding how organizations like corporations, banks, governments, the military, and police, whose purpose is to provide citizens with a decent and safe life, have been corrupted and controlled by those who exploit them to fill their own pockets and those who attempt to control and monitor the entire population under the pretext of protecting the nation from imaginary threats.

These people require a peculiar psychological state of doing what is necessary to run an organization in this way, while hiding their real motivations from themselves. George Orwell famously gave this ideological acrobatics the name "doublethink."

Those in power in Japan were accustomed to a political and cultural tradition in which tolerance of contradiction was not only permitted but essential.

The Origins of Japan's Political Structure: The Shackles of the 100 Years Since Meiji

This book basically deals with Japanese history.

Among these, it is worth recalling that the Edo period maintained peace for hundreds of years based on the strong authority of the shogunate, and achieved remarkable socioeconomic development beyond imagination.

The accumulation of wealth was centered around the merchants at the very bottom, but the enormous contradictory energy that arose from the tenacious and thorough maintenance of the class system dominated by the samurai is still useful in explaining various phenomena in Japanese society today.

This analysis is brilliant, showing how the compressed efforts of just one generation after the Meiji Restoration to break away from Asia and join the ranks of Western powers transformed the Japanese mentality and how it still serves as a shackle to Japan's future.

And the analysis that while the Meiji Restoration put forward the two "fictions" of the imperial system and the parliamentary system, in reality the main players of the Restoration practiced oligarchic politics behind the scenes, and that the large power vacuum left by their deaths in old age gave birth to the current structure of Japanese politics, which is swayed by bureaucrats without ultimate responsibility, and that the reason fundamental reform in Japan's organization is so difficult is precisely because of this culture without a place for ultimate responsibility is also insightful.

As a scholar of international political economy, the author also devotes a significant portion of the book to discussions of politics and economics after World War II.

The author clearly differs from the "new Japan experts" in the United States who act to protect the existing US-Japan relationship.

As the title suggests, the book not only criticizes Japan's chronic problems, but also unhesitatingly criticizes the United States, which bears the original sin for Japan's current problems.

The fact that the US military government was largely responsible for the difficulty of reconciling Japan's past by blocking the opportunity for the Japanese people to reflect on their own mistakes during the post-war process is something that Americans should hear with pain.

The issue of the Futenma naval base in Okinawa, which has been a hot potato in U.S.-Japan relations since the 1990s, has also been criticized for being unnecessarily prolonged and complicated due to competition and selfishness among U.S. bureaucracies.

Discussions about exchange rate policy and bubbles delve into considerable depth, allowing you to grasp the dramatic trajectory of the Japanese economy.

One of the important themes covered in this book is that after Japan's defeat in the war, it entrusted its national defense and foreign affairs to the United States, and instead used the United States as leverage to develop its economy. Later, the United States, in turn, relied on Japan's economic power to maintain a dollar-centered global economy.

The more I read this book, the more I am surprised by how many aspects of Korean society resemble those of post-war Japan.

Even though our country's economic growth model is inevitably similar to that of Japan, there are many sentences that would not be awkward at all if only the subject were changed from Japan to Korea.

Korea, which had been following Japan in this way, has gradually changed its trajectory since the late 20th century. However, I think that is why the same issues that Japan is struggling with - chronic low growth, media independence, judicial reform, and a low birth rate and aging society - are also homework for us.

An insightful analysis of what ails Japan.

- [The Economist]

"The Shackles of Japan" is an excellent and immersive introduction to Japan.

Analysis of Japanese politics and economics is also full of intellectual stimulation.

There are many lessons to be learned not only for Japan, but also for the United States and other countries.

- [Complete Review]

Murphy concretely demonstrates how Japan is dependent on the United States to maintain its existing political system and future.

The final part of the book provides an in-depth analysis of the Abe administration.

- [Publisher's Weekly]

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: February 15, 2021

- Page count, weight, size: 660 pages | 1,012g | 145*210*35mm

- ISBN13: 9788967358624

- ISBN10: 8967358628

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)