Gyeongju is the sound of a mother calling

|

Description

Book Introduction

The life of the colonized through the eyes of the colonizer

Kazue Morisaki, a native of Daegu and Gyeongju, has published his autobiography in Korean!

A poignant portrayal of the 17 years of growth in colonial Korea from 1927 to 1944.

A masterpiece of autobiographical literature that quietly captures the trajectory of the mind!

In the eyes of the young girl, the land of Joseon shone warmly like a mother.

And the sky of that land was always blue and clear.

As the principal of a school established by the Japanese in a colonial area, my father had to be aware of anti-Japanese sentiment among Koreans and was also under surveillance by the Japanese military police.

I thought the war was far away, but before I knew it, it had seeped into my life.

Without even knowing the sorrow of those who had their land and language taken away… … A girl raised by the land and ‘Omoni’ for 17 years.

She tells in detail the trajectory of her heart, containing the hope that one day she will stand on the land of her original sin, in order to live as a post-war Japanese.

What is language? What is home? What did the girl see there? A moving book that leaves readers feeling solemn!

“What Kazue Morisaki experienced as a girl in colonial Korea was ‘the sensibility of breathing with the people’ and ‘the hybridity of harmonizing differences.’

This book depicts the origin of the author's ideological trajectory, which sought to overcome the fundamental question of "What does the Korean issue mean to the Japanese people?"

How should we perceive Kazue Morisaki, who, bearing the "original sin" of being born and raised as a Japanese person in Joseon, pursued solidarity across borders?

“It is now our turn to answer Morisaki’s ‘nostalgia.’” (Professor Hyunmuam, Hokkaido University)

Kazue Morisaki, a native of Daegu and Gyeongju, has published his autobiography in Korean!

A poignant portrayal of the 17 years of growth in colonial Korea from 1927 to 1944.

A masterpiece of autobiographical literature that quietly captures the trajectory of the mind!

In the eyes of the young girl, the land of Joseon shone warmly like a mother.

And the sky of that land was always blue and clear.

As the principal of a school established by the Japanese in a colonial area, my father had to be aware of anti-Japanese sentiment among Koreans and was also under surveillance by the Japanese military police.

I thought the war was far away, but before I knew it, it had seeped into my life.

Without even knowing the sorrow of those who had their land and language taken away… … A girl raised by the land and ‘Omoni’ for 17 years.

She tells in detail the trajectory of her heart, containing the hope that one day she will stand on the land of her original sin, in order to live as a post-war Japanese.

What is language? What is home? What did the girl see there? A moving book that leaves readers feeling solemn!

“What Kazue Morisaki experienced as a girl in colonial Korea was ‘the sensibility of breathing with the people’ and ‘the hybridity of harmonizing differences.’

This book depicts the origin of the author's ideological trajectory, which sought to overcome the fundamental question of "What does the Korean issue mean to the Japanese people?"

How should we perceive Kazue Morisaki, who, bearing the "original sin" of being born and raised as a Japanese person in Joseon, pursued solidarity across borders?

“It is now our turn to answer Morisaki’s ‘nostalgia.’” (Professor Hyunmuam, Hokkaido University)

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

To Korean readers

letter

Chapter 1: The Milky Way

Chapter 2: Azalea leaves

Chapter 3 Royal Tombs

Chapter 4: Soul Fire

Cross-dressing

Reviews

Morisaki Kazue Chronology

Translator's Note

letter

Chapter 1: The Milky Way

Chapter 2: Azalea leaves

Chapter 3 Royal Tombs

Chapter 4: Soul Fire

Cross-dressing

Reviews

Morisaki Kazue Chronology

Translator's Note

Into the book

We play together, the four of us, with my sister always following me and my brother, while my mother prepares dinner.

I went down the hill and crossed the wide road between the upper and lower army quarters to the pond.

My younger brother is crawling on the grass.

My sister and I picked mulberry fruits.

A Korean man and woman hurrying home pass by on a wide road.

“Have you eaten yet?” “What did that mother say?” “I asked if you had eaten.” “You haven’t eaten yet.”

--- p.61

My father told my mother that Mr. Kim was a relative of a high-ranking person in Joseon named Kim Ok-gyun.

He was also a relative of the old king, and his parents lived in Gyeongseong.

My mother told me that the children of Mr. Kim's family were well-mannered, so I should emulate them.

When talking to their parents, whether boys or girls, they sat up straight and spoke in Korean.

He spoke to me in Japanese.

The book was in Japanese.

--- p.80

“It’s full of honey,” says a classmate.

“It’s true.

“But my father said not to call me honey.” “Why? My father said to call me honey.” This conversation was also drowned out by the noisy chatter.

Japanese people use the word "honey" to refer to Koreans in a derogatory way.

It's embarrassing to hear.

When Koreans call each other, they say 'Honey!' or 'Hello?'

But Japanese people write things like “Honey, you’re so pretty.”

--- p.134~135

Among them, there was someone who seemed like a grown man even to a child like me.

Mr. Choi Geung, a gentle and honest man with a white beard, always has a big smile on his face, tolerating even the rude behavior of the Japanese.

He seemed to be quietly watching his father, who was deeply troubled by the Japanese middle school official who was causing trouble.

It had that much style.

--- p.179

I appeared in a school play and danced wearing Joseon clothing.

I forgot the title of the play.

But it was about the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

I volunteered to play the role of a Korean daughter.

By that time, I had stopped messing around with the Emperor's shit, but I still felt very ambiguous when I heard my teacher say, "How dare you", and talk about the Imperial Family.

--- p.224

In Korean, mother is called 'Omoni'.

Joseon, reflected in the mind of a child, must have been a world of Omoni.

I thought that an individual's home was like a flower blooming in the vast world, and that the world was a place where, in addition to the sky, trees, and wind, many Koreans lived and mixed with Japanese.

I always felt like I was being watched over by complete strangers.

I went down the hill and crossed the wide road between the upper and lower army quarters to the pond.

My younger brother is crawling on the grass.

My sister and I picked mulberry fruits.

A Korean man and woman hurrying home pass by on a wide road.

“Have you eaten yet?” “What did that mother say?” “I asked if you had eaten.” “You haven’t eaten yet.”

--- p.61

My father told my mother that Mr. Kim was a relative of a high-ranking person in Joseon named Kim Ok-gyun.

He was also a relative of the old king, and his parents lived in Gyeongseong.

My mother told me that the children of Mr. Kim's family were well-mannered, so I should emulate them.

When talking to their parents, whether boys or girls, they sat up straight and spoke in Korean.

He spoke to me in Japanese.

The book was in Japanese.

--- p.80

“It’s full of honey,” says a classmate.

“It’s true.

“But my father said not to call me honey.” “Why? My father said to call me honey.” This conversation was also drowned out by the noisy chatter.

Japanese people use the word "honey" to refer to Koreans in a derogatory way.

It's embarrassing to hear.

When Koreans call each other, they say 'Honey!' or 'Hello?'

But Japanese people write things like “Honey, you’re so pretty.”

--- p.134~135

Among them, there was someone who seemed like a grown man even to a child like me.

Mr. Choi Geung, a gentle and honest man with a white beard, always has a big smile on his face, tolerating even the rude behavior of the Japanese.

He seemed to be quietly watching his father, who was deeply troubled by the Japanese middle school official who was causing trouble.

It had that much style.

--- p.179

I appeared in a school play and danced wearing Joseon clothing.

I forgot the title of the play.

But it was about the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

I volunteered to play the role of a Korean daughter.

By that time, I had stopped messing around with the Emperor's shit, but I still felt very ambiguous when I heard my teacher say, "How dare you", and talk about the Imperial Family.

--- p.224

In Korean, mother is called 'Omoni'.

Joseon, reflected in the mind of a child, must have been a world of Omoni.

I thought that an individual's home was like a flower blooming in the vast world, and that the world was a place where, in addition to the sky, trees, and wind, many Koreans lived and mixed with Japanese.

I always felt like I was being watched over by complete strangers.

--- p.284

Publisher's Review

The suffering of the second generation of colonial subjects who fell in love with Joseon

This book, "Gyeongju is the Sound of Mother Calling," is a memoir written by Kazue Morisaki, who was born in the Korean Peninsula in 1927, and covers the 17 years he spent there.

This book, which reflects on the 17 years she spent in Joseon, torn between her personal attachment to the land that embraced her as the daughter of a colonist and the historical and national responsibilities she must bear, depicts the pain of a second-generation colonist who loved the motherly affection of "colonial Joseon" and the Joseon that was like that mother.

After being published by Shinchosha in 1984, it was published by Chikuma Shobo in 1995 and Yosensha in 2006.

It can be said that this is a book that has been read for a long time in Japan.

Morisaki said of this work, “Writing about my colonial experience was painful, but I was concerned about the irreversible nature of history, and I hoped it could serve as a testimony for future generations. So, I wrote it by rereading as much of my personal information as possible, and limiting it to the time period.”

Morisaki meticulously described the daily lives of Japanese people in colonial Korea by comparing his own experiences with historical materials he read after the war.

Morisaki described his collected works, published in 2008, as “a chronicle of my struggles to correct the distorted sense of original sin felt by second-generation Japanese during colonial rule.”

For her, the sense of original sin from having been born and raised in colonial Korea was severe.

At the same time, it was the very core of her writing.

In other words, this book provides a clue to the daily lives of Japanese people living in colonial Korea, while also providing a background for reading the works of Kazue Morisaki, which cover a wide range of topics.

Who is Kazue Morisaki?

Kazue Morisaki was a poet and writer who lived and worked in a coal mining village.

In Japan, she is also known as a pioneering feminist.

She was born in 1927 in Korea under Japanese colonial rule.

And in 1944, she went to Japan to enter Fukuoka Prefectural Women's College.

After the war, he worked for the poetry magazine "Moon" (母音) edited by Yutaka Maruyama.

Also, in 1958, he moved to Nakama, a coal mining town in the Chikuho region, with poet Kan Tanigawa, and started a cultural movement called "Circle Village."

And from August 1959 to July 1961, she also published the women's magazine "Nameless Communications."

Coal quarried from coal mines played a significant role in Japan's modernization, which began in the late 19th century.

However, between the late 1950s and the 1960s, as Japan's energy source shifted from coal to oil, coal mining towns underwent major changes.

It was around this time that she lived in a coal mining town, and everyone involved in the coal mining industry had to endure and fight against these changes and the resulting hardships.

And from 1979, he lived in a place called Munakata and continued his literary activities.

Morisaki, who was born in a colony, can be said to have worked with special interest and affection for those who could be considered socially disadvantaged.

The topics Morisaki has dealt with are diverse, including colonial issues, women's issues, coal mining history, labor issues, the imperial system, nationalism, the environment, and life.

There are also many books about Joseon and Korea.

『Gyeongju is the sound of my mother calling: My hometown』(1984), 『Into the Echoing Mountains and Rivers: A Korean Journey in the Spring of 1985』(1986), 『Two Languages, Two Hearts: A Second-Generation Japanese Colony After the War』(1995), 『Love is Waiting: A Message to the 21st Century』(1999, a book about Kim Im-soon, the director of Geoje Island Aegwangwon, a classmate from a girls' school and recipient of the Magsaysay Award in 1989).

In 2008, the complete works "Morisaki Kazue Collection: A Journey into the History of Mentality" (5 volumes) were published by Fujiwara Shoten.

When publishing the complete works, leading Japanese writers such as Shunsuke Tsurumi, Chizuko Ueno, and Sangjung Kang were invited.

Researchers active in wrote letters of recommendation.

About the translation process of this book

What is particularly noteworthy about this translation and publication in Korea is that the text describes in detail the environment in which she and her family lived (Daegu, Gyeongju, and Gimcheon).

It's not just a background thing.

Daegu, Gyeongju, and Gimcheon are the molds that shaped her, and the nature and people of the Korean Peninsula occupy a very important place in this book.

This detailed description of the Korean Peninsula became the impetus for publishing a translation in Korea.

This book was actually translated and published in Korea through exchanges with people from Daegu, her birthplace.

Since 2001, a civic movement has been underway in which citizens directly investigate and record the history of the physical spaces remaining in the city, thereby creating a new local history.

Then, I began to think that I needed materials from the Japanese colonial period, but since it was difficult to obtain such materials in Korea, I began to feel regret for the missing materials.

As a result, the civil movement developed a strong interest in the materials and texts remaining in Japan.

Because such stories are needed to interpret the physical space of the city.

Co-translator Rie Matsui has been conducting on-site research on village development in Samdeok-dong (formerly Samrip-jeong), Morisaki's birthplace, since 2003.

At the time, there were many Japanese-style houses (confiscated houses) remaining in Samdeok-dong, so Rie Matsui became interested in them and came into contact with the aforementioned civil movement.

Rie Matsui, who was searching for a text about Daegu during the Japanese colonial period, discovered the existence of this book in 2006.

And I introduce the book to my acquaintances who live in Daegu.

In 2007, the aforementioned civic movement published the results of its field research as 『Daegu Shintaekriji』.

And Matsui Rie delivered 『Daegu Shintaekriji』 to Mr. Morisaki.

This became the impetus for an exchange of letters between the two.

In 2008, Rie Matsui continued her relationship with Morisaki by visiting him in Munakata City, Fukuoka Prefecture.

In 2013, the joint activities of civil society and the Daegu Jung-gu Office were well-received and received the Asian Cityscape Award ('Urban Regeneration Project through Rediscovery of Daegu').

At this time, Kwon Sang-goo, who was attending the awards ceremony held in Fukuoka, made a separate schedule to visit Morisaki in Munakata.

The direct trigger for the book translation and publishing movement was Kwon Sang-goo's visit to Imunakata.

Rie Matsui, who accompanied him as his interpreter, received permission from Morisaki to publish the Korean translation.

Afterwards, Seungju Park and Rie Matsui, who are members of the aforementioned 'Daegu Reading Group' and currently run 'Daegu Haru', a private Korea-Japan exchange hub, carried out the translation work in a joint translation format.

First, Seung-ju Park did a rough translation, then Rie Matsui checked it against the original text, and then Seung-ju Park finished the translation.

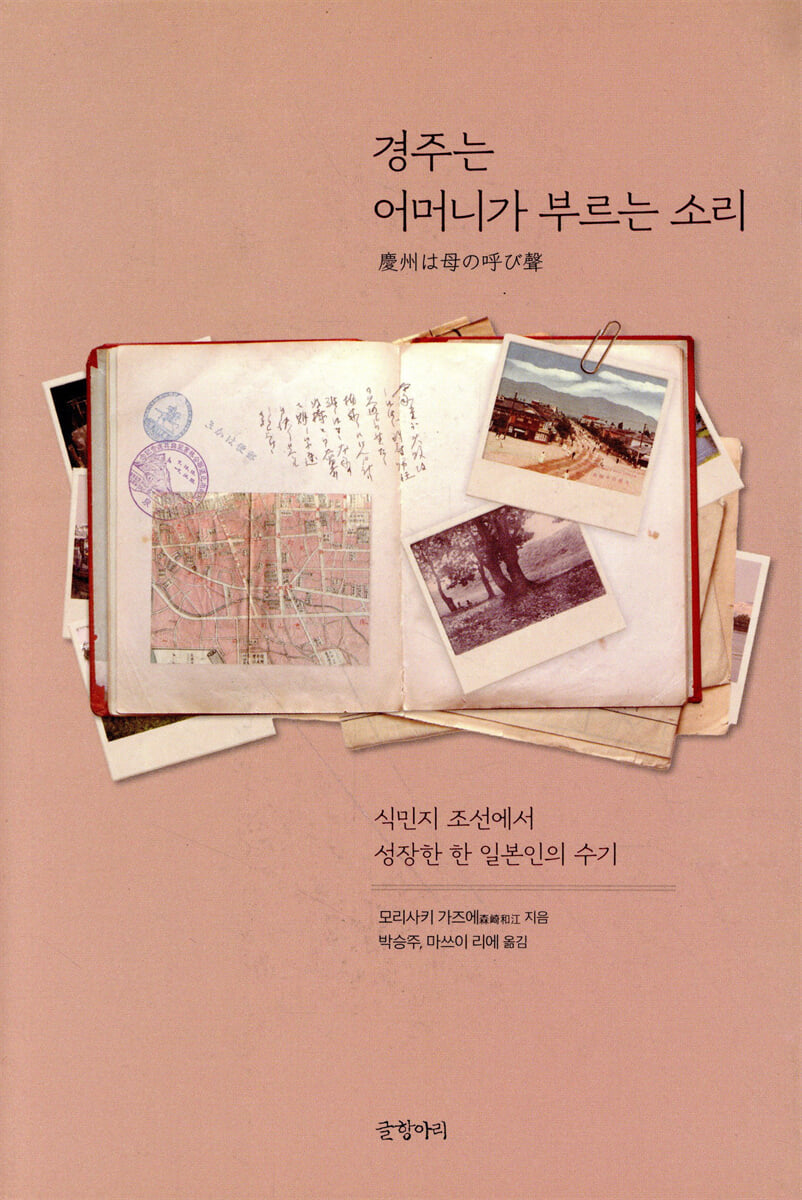

This book also contains many postcards, photographs, and maps from the Japanese colonial period, and the Daegu data is from materials collected by Kwon Sang-gu over a period of about 15 years.

Morisaki wrote this book to convey the story of Korea during the Japanese colonial period to young Japanese people.

So, the translators also wanted to introduce the story of colonial Joseon to young Koreans, and this material was indispensable for this translation and publication.

This book, "Gyeongju is the Sound of Mother Calling," is a memoir written by Kazue Morisaki, who was born in the Korean Peninsula in 1927, and covers the 17 years he spent there.

This book, which reflects on the 17 years she spent in Joseon, torn between her personal attachment to the land that embraced her as the daughter of a colonist and the historical and national responsibilities she must bear, depicts the pain of a second-generation colonist who loved the motherly affection of "colonial Joseon" and the Joseon that was like that mother.

After being published by Shinchosha in 1984, it was published by Chikuma Shobo in 1995 and Yosensha in 2006.

It can be said that this is a book that has been read for a long time in Japan.

Morisaki said of this work, “Writing about my colonial experience was painful, but I was concerned about the irreversible nature of history, and I hoped it could serve as a testimony for future generations. So, I wrote it by rereading as much of my personal information as possible, and limiting it to the time period.”

Morisaki meticulously described the daily lives of Japanese people in colonial Korea by comparing his own experiences with historical materials he read after the war.

Morisaki described his collected works, published in 2008, as “a chronicle of my struggles to correct the distorted sense of original sin felt by second-generation Japanese during colonial rule.”

For her, the sense of original sin from having been born and raised in colonial Korea was severe.

At the same time, it was the very core of her writing.

In other words, this book provides a clue to the daily lives of Japanese people living in colonial Korea, while also providing a background for reading the works of Kazue Morisaki, which cover a wide range of topics.

Who is Kazue Morisaki?

Kazue Morisaki was a poet and writer who lived and worked in a coal mining village.

In Japan, she is also known as a pioneering feminist.

She was born in 1927 in Korea under Japanese colonial rule.

And in 1944, she went to Japan to enter Fukuoka Prefectural Women's College.

After the war, he worked for the poetry magazine "Moon" (母音) edited by Yutaka Maruyama.

Also, in 1958, he moved to Nakama, a coal mining town in the Chikuho region, with poet Kan Tanigawa, and started a cultural movement called "Circle Village."

And from August 1959 to July 1961, she also published the women's magazine "Nameless Communications."

Coal quarried from coal mines played a significant role in Japan's modernization, which began in the late 19th century.

However, between the late 1950s and the 1960s, as Japan's energy source shifted from coal to oil, coal mining towns underwent major changes.

It was around this time that she lived in a coal mining town, and everyone involved in the coal mining industry had to endure and fight against these changes and the resulting hardships.

And from 1979, he lived in a place called Munakata and continued his literary activities.

Morisaki, who was born in a colony, can be said to have worked with special interest and affection for those who could be considered socially disadvantaged.

The topics Morisaki has dealt with are diverse, including colonial issues, women's issues, coal mining history, labor issues, the imperial system, nationalism, the environment, and life.

There are also many books about Joseon and Korea.

『Gyeongju is the sound of my mother calling: My hometown』(1984), 『Into the Echoing Mountains and Rivers: A Korean Journey in the Spring of 1985』(1986), 『Two Languages, Two Hearts: A Second-Generation Japanese Colony After the War』(1995), 『Love is Waiting: A Message to the 21st Century』(1999, a book about Kim Im-soon, the director of Geoje Island Aegwangwon, a classmate from a girls' school and recipient of the Magsaysay Award in 1989).

In 2008, the complete works "Morisaki Kazue Collection: A Journey into the History of Mentality" (5 volumes) were published by Fujiwara Shoten.

When publishing the complete works, leading Japanese writers such as Shunsuke Tsurumi, Chizuko Ueno, and Sangjung Kang were invited.

Researchers active in wrote letters of recommendation.

About the translation process of this book

What is particularly noteworthy about this translation and publication in Korea is that the text describes in detail the environment in which she and her family lived (Daegu, Gyeongju, and Gimcheon).

It's not just a background thing.

Daegu, Gyeongju, and Gimcheon are the molds that shaped her, and the nature and people of the Korean Peninsula occupy a very important place in this book.

This detailed description of the Korean Peninsula became the impetus for publishing a translation in Korea.

This book was actually translated and published in Korea through exchanges with people from Daegu, her birthplace.

Since 2001, a civic movement has been underway in which citizens directly investigate and record the history of the physical spaces remaining in the city, thereby creating a new local history.

Then, I began to think that I needed materials from the Japanese colonial period, but since it was difficult to obtain such materials in Korea, I began to feel regret for the missing materials.

As a result, the civil movement developed a strong interest in the materials and texts remaining in Japan.

Because such stories are needed to interpret the physical space of the city.

Co-translator Rie Matsui has been conducting on-site research on village development in Samdeok-dong (formerly Samrip-jeong), Morisaki's birthplace, since 2003.

At the time, there were many Japanese-style houses (confiscated houses) remaining in Samdeok-dong, so Rie Matsui became interested in them and came into contact with the aforementioned civil movement.

Rie Matsui, who was searching for a text about Daegu during the Japanese colonial period, discovered the existence of this book in 2006.

And I introduce the book to my acquaintances who live in Daegu.

In 2007, the aforementioned civic movement published the results of its field research as 『Daegu Shintaekriji』.

And Matsui Rie delivered 『Daegu Shintaekriji』 to Mr. Morisaki.

This became the impetus for an exchange of letters between the two.

In 2008, Rie Matsui continued her relationship with Morisaki by visiting him in Munakata City, Fukuoka Prefecture.

In 2013, the joint activities of civil society and the Daegu Jung-gu Office were well-received and received the Asian Cityscape Award ('Urban Regeneration Project through Rediscovery of Daegu').

At this time, Kwon Sang-goo, who was attending the awards ceremony held in Fukuoka, made a separate schedule to visit Morisaki in Munakata.

The direct trigger for the book translation and publishing movement was Kwon Sang-goo's visit to Imunakata.

Rie Matsui, who accompanied him as his interpreter, received permission from Morisaki to publish the Korean translation.

Afterwards, Seungju Park and Rie Matsui, who are members of the aforementioned 'Daegu Reading Group' and currently run 'Daegu Haru', a private Korea-Japan exchange hub, carried out the translation work in a joint translation format.

First, Seung-ju Park did a rough translation, then Rie Matsui checked it against the original text, and then Seung-ju Park finished the translation.

This book also contains many postcards, photographs, and maps from the Japanese colonial period, and the Daegu data is from materials collected by Kwon Sang-gu over a period of about 15 years.

Morisaki wrote this book to convey the story of Korea during the Japanese colonial period to young Japanese people.

So, the translators also wanted to introduce the story of colonial Joseon to young Koreans, and this material was indispensable for this translation and publication.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: November 25, 2020

- Page count, weight, size: 296 pages | 468g | 145*217*20mm

- ISBN13: 9788967358358

- ISBN10: 8967358350

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)