100-year meal

|

Description

Book Introduction

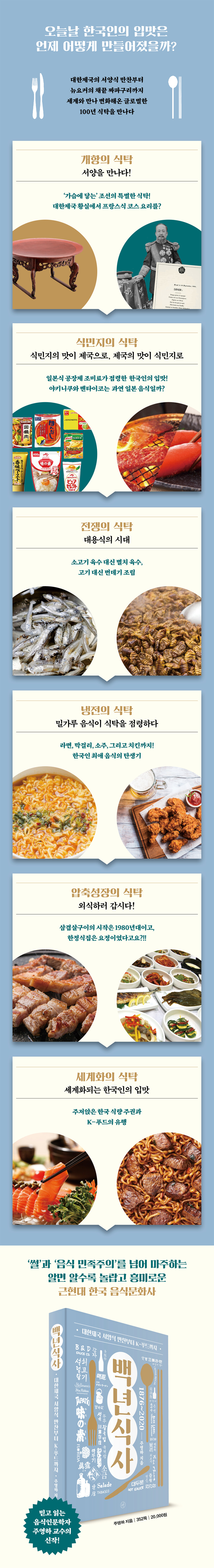

When and how did today's Korean palate develop? From Western-style banquets in the Korean Empire to New Yorkers' chapaghetti japaguri Meet the 100-year-old global dining table that has changed through meeting the world! Korean food and the Korean diet have evolved over the past 100 years, mingling with and encountering diverse world cultures amidst the rapid changes of the times. Professor Joo Young-ha, a food humanist who provides the most reliable history of food culture, meticulously analyzes a vast and diverse body of data to trace the Korean Peninsula's incorporation into the global food system from the opening of ports to the present, dividing it into six periods and vividly illustrating how Koreans' dining tables and tastes have changed. From the Western-style banquets of the Korean Empire to today's K-food trends, let's enjoy 100 years of global Korean dining together. |

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

In publishing the book

Prologue: The Formation of the Global Food System and the History of the Incorporation of the Korean Peninsula

Part 1: The Table of the Opening Ports - Encounters with Exotic Cuisine

1 Korean food described by American George Polk

2 Western food eaten by Kim Deuk-ryeon during his world tour

3 French course meal prepared by Emma Kroebel in Seoul

4. Korean lunch that Alice Roosevelt had with Emperor Gojong

5 Beer and whiskey drunk at the royal wedding

Part 2: Colonial Tables - Japanese Cuisine in Korea and Korean Cuisine in Japan

1. The trend of Japanese tofu and shaved ice

2 From Cheongguk Udon to Udon

3 Ajinomoto, the Japanese seasoning that permeates our tables

4. Japanese Jangyu that achieved the fusion of Japan and the West

Yakiniku and Karashi Mentaiko Moved to the Five Empires

Part 3: The War Table: A Diet of Rationing, Control, and Relief

1. “Let’s all save rice and eat substitute food.”

2 What should I eat instead of beef?

Hotteok and somen noodles attract attention with the promotion of 3-double meals

4. Street food in Cheonggyecheon during the liberation period

5 Relief supplies: milk porridge and a Hakkobang bar in Busan

Part 4: The Cold War Table: The Influx of American Agricultural Surplus and the Green Revolution

1. Establishing North Korea's National Cuisine

2 Chicken Ramen, Beef Ramen, and K-ration

3. The trend of wheat makgeolli and diluted soju

4. Increase in soybean oil production and fried foods

5 Green Revolution and Unified Rice

Part 5: The Table of Compressed Growth - The Warring States Period of Eating Business

1. The appearance of LA galbi and grilled pork belly

2 Food Industry: War-Like Competition

3 Soft drinks, hot promotions

4. A restaurant that blossomed in the pursuit of health

5. Gangnam development completed and a boom in high-end restaurants opening.

Part 6: The Table of Globalization: The Global Food System That Dominates Koreans' Tables

1 Tropical fruit import boom

2. Increased consumption of Western vegetables and seed property rights

3 Salmon and Lobster Become Popular Seafoods

4 Globalized Spicy Flavors

5 Changing tastes in the process of globalization

Epilogue: Reflections for the Next 100 Years

Notes in the text | References | Image sources and locations | Search

Prologue: The Formation of the Global Food System and the History of the Incorporation of the Korean Peninsula

Part 1: The Table of the Opening Ports - Encounters with Exotic Cuisine

1 Korean food described by American George Polk

2 Western food eaten by Kim Deuk-ryeon during his world tour

3 French course meal prepared by Emma Kroebel in Seoul

4. Korean lunch that Alice Roosevelt had with Emperor Gojong

5 Beer and whiskey drunk at the royal wedding

Part 2: Colonial Tables - Japanese Cuisine in Korea and Korean Cuisine in Japan

1. The trend of Japanese tofu and shaved ice

2 From Cheongguk Udon to Udon

3 Ajinomoto, the Japanese seasoning that permeates our tables

4. Japanese Jangyu that achieved the fusion of Japan and the West

Yakiniku and Karashi Mentaiko Moved to the Five Empires

Part 3: The War Table: A Diet of Rationing, Control, and Relief

1. “Let’s all save rice and eat substitute food.”

2 What should I eat instead of beef?

Hotteok and somen noodles attract attention with the promotion of 3-double meals

4. Street food in Cheonggyecheon during the liberation period

5 Relief supplies: milk porridge and a Hakkobang bar in Busan

Part 4: The Cold War Table: The Influx of American Agricultural Surplus and the Green Revolution

1. Establishing North Korea's National Cuisine

2 Chicken Ramen, Beef Ramen, and K-ration

3. The trend of wheat makgeolli and diluted soju

4. Increase in soybean oil production and fried foods

5 Green Revolution and Unified Rice

Part 5: The Table of Compressed Growth - The Warring States Period of Eating Business

1. The appearance of LA galbi and grilled pork belly

2 Food Industry: War-Like Competition

3 Soft drinks, hot promotions

4. A restaurant that blossomed in the pursuit of health

5. Gangnam development completed and a boom in high-end restaurants opening.

Part 6: The Table of Globalization: The Global Food System That Dominates Koreans' Tables

1 Tropical fruit import boom

2. Increased consumption of Western vegetables and seed property rights

3 Salmon and Lobster Become Popular Seafoods

4 Globalized Spicy Flavors

5 Changing tastes in the process of globalization

Epilogue: Reflections for the Next 100 Years

Notes in the text | References | Image sources and locations | Search

Detailed image

Into the book

I am a baby boomer born after the Korean War.

I was born when compressed growth was just beginning, I tasted cider and cola, I memorized the National Education Charter faster than anyone else at school and received bread as a prize, and around 1972, I was even tested at lunchtime to see if my lunchbox had white rice or mixed grain rice.

In the fall of 2016, when I told this story in a graduate school class, the students' eyes widened in wonder.

In the end, the class that day started with 'When I was young' and continued with stories from that time.

When I look back at the students' reactions at that time, my experiences in the 1960s and 1970s were a part of their history.

… … The stories in this book may be like ‘old tales’ to them.

Even though it's a bit long and boring, I ask you to listen at least once.

That's because only then can you know what historical process the food on your table has gone through.

--- p.5~7 From “Publishing a Book”

I believe that most of the food consumed by Koreans today is built around these six keywords.

The five periods of opening of ports, colonization, war, the Cold War, and compressed growth were the process of the Korean Peninsula being incorporated into the global food system.

However, as globalization became widespread in the 1990s, food and beverages produced in Korea began to spread to other countries.

When the film "Parasite" won an award at the 2020 Academy Awards, eating "Chae-kkeut Jjapaguri" became a trend among New Yorkers.

The reason they were able to eat that food was because Korea was already a key player in the global food system.

Among the foods consumed by Koreans today, there are both good and bad foods, depending on the tastes of individuals and communities.

While individual and community food preferences are inherently subjective, they are also, from another perspective, a product of history.

In this book, I will examine the history of Korean food habits over the past 145 years by wearing six different glasses from time to time.

--- p.14~15, from “Prologue: The Formation of the World Food System and the History of the Incorporation of the Korean Peninsula”

American George Clayton Foulk (1856-1893) is a representative foreigner who ate Korean food while traveling around the Korean Peninsula.

… … In the Jeonju Gamyeong’s quarters, Fork slept on a bed made of several blankets.

The next day, Fork woke up at 8 o'clock and ate honey, chestnuts, and persimmons for breakfast, which had already been brought into the room at 9 o'clock.

At ten o'clock, the magistrate sent a meal specially for Fork.

Fork wrote in his diary about the table set with food, “on a table reaching my breast.”

Fork also described the meal he received as excellent and described the table setting in his diary.

--- p.23~26, from Part 1, Chapter 1, “Korean Food Described by American George Polk”

Looking at this menu, one question arises.

Where on earth did the Korean Imperial Family get asparagus, olives, foie gras, truffles, pineapple, ice cream, and chocolate from in 1905 to prepare such a wealth of French cuisine? At the time, French ingredients were being canned and exported to countries around the world.

The Imperial kitchen of the Korean Empire also purchased canned food through Western European trading houses in Seoul.

Chocolate, of course, but also French cognac, wine, and champagne were prepared in the same way.

The kitchen was also equipped with cooking utensils for making cakes and ice cream.

So, it would not have been difficult for Kroebel to prepare French cuisine.

--- p.41~42, from Part 1, Chapter 3, “French Course Meal Prepared by Emma Kroebel in Seoul”

Ajinomoto's advertising, aimed at restaurant owners, was very specific.

The headline of the advertisement on page 6 of the October 22, 1929 edition of the Dong-A Ilbo was “Restaurant.”

“Everyone who chooses a restaurant is looking for a place that makes food delicious.

Restaurants that serve delicious food are places that use Ajinomoto well.

He wrote, “Don’t forget to try Ajinomoto with cold noodles, janggukbap, tteokguk, daegutang, and seolleongtang.”

This is an advertisement that says to always add Ajinomoto to dishes that contain soup.

… … In the middle of summer, it was difficult to prepare dongchimi at a cold noodle restaurant, so it was expensive to make the broth separately, but using Ajinomoto was much more economical.

In the end, the taste of Pyongyang Mul Naengmyeon's broth was dominated by Ajinomoto's monosodium glutamate.

--- p.80~83, from Part 2, Chapter 3, “Ajinomoto, the Japanese seasoning that has permeated the dining table”

Until the 1970s, each farm had one or two pigs, and they were raised mainly on food scraps rather than special feed.

The meat of pigs raised this way had a foul odor.

So, the wealthy class did not prefer pork.

However, as beef prices skyrocketed in the 1960s and 1970s, the government actively encouraged the consumption of pork along with chicken as a substitute to stabilize meat prices.

… … The fact that it was significantly cheaper than beef was a major factor in the popularity of grilled pork belly in the 1980s, but on the other hand, the Japanese portable gas burner and disposable butane gas that were released in Korea in June 1980 also played a big role.

As economic growth brought about more leisure, people began to go on outings with family and friends more frequently.

From this time on, it became popular to grill pork belly outdoors using a portable gas burner.

After all, since the 1990s, grilled pork belly has become one of Koreans' favorite meat dishes.

--- p.205~207, from Part 5, Chapter 1, “The Appearance of LA Galbi and Grilled Pork Belly”

Even in the 1980s, apartment prices in Gangnam skyrocketed, and Gangnam's emerging middle class had more money than ever before.

However, in Gangnam, there was no suitable place for the emerging middle class to spend leisure time with their families.

Since then, large, upscale restaurants such as Samwon Garden in Sinsa-dong, which opened in November 1981, Neulbom and Seorabeol in Nonhyeon-dong, and Chosung Park and Shillajeong in Seocho-dong have become popular holiday family outing destinations.

The large, upscale restaurants that mainly sold ribs and cold noodles were called 'Luxury Galbi Town', 'Countryside Galbi House', and 'Gongwonsik Galbi House'.

As the name suggests, this restaurant, a park-style rib house, is situated on a vast 1,000-pyeong site with high-quality ornamental trees, an artificial waterfall, a cloud bridge, a watermill, a pavilion, a stone pagoda, a fountain, a pond, an aquarium, and other facilities, so much so that it could almost be called a park.

--- p.235, from Part 5, Chapter 5, “Completion of Gangnam Development and the Boom of High-End Restaurant Openings”

Western vegetables that have been widely cultivated since the 2000s include broccoli, lettuce, and bell peppers.

… … But the problem is that the more Western vegetables Koreans eat, the more foreign currency is spent on buying foreign seeds.

… … In this age of globalization, securing property rights to agricultural seeds is food sovereignty and food security itself.

This is why you need to know who the seeds of the lettuce that goes into salads, which are a must-have menu item at mid-priced Korean restaurants, the bell peppers used as an ingredient in japchae, and the broccoli that comes as a side dish for boiled fish come from.

--- p.261~263, from Part 6, Chapter 2, “Increased Consumption of Western Vegetables and Seed Property Rights”

The popularity of K-food overseas is the result of efforts by food and beverage manufacturers and restaurant workers since the mid-1960s to adapt foreign foods to Korean tastes.

Added to this are consumer reactions to new and unfamiliar processed foods.

During the period of compressed growth, most things, from processed foods to street food, took the path of localization, or Koreanization.

Korean processed foods and restaurant menus have been well-received by foreigners visiting Korea in the era of globalization, when Korean society has opened up to the outside world.

The popularity of K-food is also a result of the sociocultural hybridization that Korean society has embraced through compressed growth and globalization.

--- p.292~293, from “Epilogue: Reflections for the Next 100 Years”

Since the mid-1980s, several Western European countries, including the United States, have been strongly requesting the Korean government to import agricultural, livestock and fishery products.

Farmers opposed the opening of the market and demanded that the government take measures to protect agricultural, livestock and fishery products.

The power elite, who prioritized economic growth through the export of manufactured goods, perceived the agricultural sector as an obstacle to greater trade and higher growth.

In the age of globalization, Korea's food sovereignty has fallen to rock bottom.

In these difficult times, the cliché “traditional food is the best” is prevalent across government, academia, the media, and business circles.

'Food nationalism' can be a very effective strategy for recovering the property rights to agricultural, livestock and fishery products lost after the last IMF foreign exchange crisis.

However, 'closed' food nationalism is not the answer to eradicating the dark shadows cast on the Korean diet and food that have breathlessly navigated the past 100 years.

I was born when compressed growth was just beginning, I tasted cider and cola, I memorized the National Education Charter faster than anyone else at school and received bread as a prize, and around 1972, I was even tested at lunchtime to see if my lunchbox had white rice or mixed grain rice.

In the fall of 2016, when I told this story in a graduate school class, the students' eyes widened in wonder.

In the end, the class that day started with 'When I was young' and continued with stories from that time.

When I look back at the students' reactions at that time, my experiences in the 1960s and 1970s were a part of their history.

… … The stories in this book may be like ‘old tales’ to them.

Even though it's a bit long and boring, I ask you to listen at least once.

That's because only then can you know what historical process the food on your table has gone through.

--- p.5~7 From “Publishing a Book”

I believe that most of the food consumed by Koreans today is built around these six keywords.

The five periods of opening of ports, colonization, war, the Cold War, and compressed growth were the process of the Korean Peninsula being incorporated into the global food system.

However, as globalization became widespread in the 1990s, food and beverages produced in Korea began to spread to other countries.

When the film "Parasite" won an award at the 2020 Academy Awards, eating "Chae-kkeut Jjapaguri" became a trend among New Yorkers.

The reason they were able to eat that food was because Korea was already a key player in the global food system.

Among the foods consumed by Koreans today, there are both good and bad foods, depending on the tastes of individuals and communities.

While individual and community food preferences are inherently subjective, they are also, from another perspective, a product of history.

In this book, I will examine the history of Korean food habits over the past 145 years by wearing six different glasses from time to time.

--- p.14~15, from “Prologue: The Formation of the World Food System and the History of the Incorporation of the Korean Peninsula”

American George Clayton Foulk (1856-1893) is a representative foreigner who ate Korean food while traveling around the Korean Peninsula.

… … In the Jeonju Gamyeong’s quarters, Fork slept on a bed made of several blankets.

The next day, Fork woke up at 8 o'clock and ate honey, chestnuts, and persimmons for breakfast, which had already been brought into the room at 9 o'clock.

At ten o'clock, the magistrate sent a meal specially for Fork.

Fork wrote in his diary about the table set with food, “on a table reaching my breast.”

Fork also described the meal he received as excellent and described the table setting in his diary.

--- p.23~26, from Part 1, Chapter 1, “Korean Food Described by American George Polk”

Looking at this menu, one question arises.

Where on earth did the Korean Imperial Family get asparagus, olives, foie gras, truffles, pineapple, ice cream, and chocolate from in 1905 to prepare such a wealth of French cuisine? At the time, French ingredients were being canned and exported to countries around the world.

The Imperial kitchen of the Korean Empire also purchased canned food through Western European trading houses in Seoul.

Chocolate, of course, but also French cognac, wine, and champagne were prepared in the same way.

The kitchen was also equipped with cooking utensils for making cakes and ice cream.

So, it would not have been difficult for Kroebel to prepare French cuisine.

--- p.41~42, from Part 1, Chapter 3, “French Course Meal Prepared by Emma Kroebel in Seoul”

Ajinomoto's advertising, aimed at restaurant owners, was very specific.

The headline of the advertisement on page 6 of the October 22, 1929 edition of the Dong-A Ilbo was “Restaurant.”

“Everyone who chooses a restaurant is looking for a place that makes food delicious.

Restaurants that serve delicious food are places that use Ajinomoto well.

He wrote, “Don’t forget to try Ajinomoto with cold noodles, janggukbap, tteokguk, daegutang, and seolleongtang.”

This is an advertisement that says to always add Ajinomoto to dishes that contain soup.

… … In the middle of summer, it was difficult to prepare dongchimi at a cold noodle restaurant, so it was expensive to make the broth separately, but using Ajinomoto was much more economical.

In the end, the taste of Pyongyang Mul Naengmyeon's broth was dominated by Ajinomoto's monosodium glutamate.

--- p.80~83, from Part 2, Chapter 3, “Ajinomoto, the Japanese seasoning that has permeated the dining table”

Until the 1970s, each farm had one or two pigs, and they were raised mainly on food scraps rather than special feed.

The meat of pigs raised this way had a foul odor.

So, the wealthy class did not prefer pork.

However, as beef prices skyrocketed in the 1960s and 1970s, the government actively encouraged the consumption of pork along with chicken as a substitute to stabilize meat prices.

… … The fact that it was significantly cheaper than beef was a major factor in the popularity of grilled pork belly in the 1980s, but on the other hand, the Japanese portable gas burner and disposable butane gas that were released in Korea in June 1980 also played a big role.

As economic growth brought about more leisure, people began to go on outings with family and friends more frequently.

From this time on, it became popular to grill pork belly outdoors using a portable gas burner.

After all, since the 1990s, grilled pork belly has become one of Koreans' favorite meat dishes.

--- p.205~207, from Part 5, Chapter 1, “The Appearance of LA Galbi and Grilled Pork Belly”

Even in the 1980s, apartment prices in Gangnam skyrocketed, and Gangnam's emerging middle class had more money than ever before.

However, in Gangnam, there was no suitable place for the emerging middle class to spend leisure time with their families.

Since then, large, upscale restaurants such as Samwon Garden in Sinsa-dong, which opened in November 1981, Neulbom and Seorabeol in Nonhyeon-dong, and Chosung Park and Shillajeong in Seocho-dong have become popular holiday family outing destinations.

The large, upscale restaurants that mainly sold ribs and cold noodles were called 'Luxury Galbi Town', 'Countryside Galbi House', and 'Gongwonsik Galbi House'.

As the name suggests, this restaurant, a park-style rib house, is situated on a vast 1,000-pyeong site with high-quality ornamental trees, an artificial waterfall, a cloud bridge, a watermill, a pavilion, a stone pagoda, a fountain, a pond, an aquarium, and other facilities, so much so that it could almost be called a park.

--- p.235, from Part 5, Chapter 5, “Completion of Gangnam Development and the Boom of High-End Restaurant Openings”

Western vegetables that have been widely cultivated since the 2000s include broccoli, lettuce, and bell peppers.

… … But the problem is that the more Western vegetables Koreans eat, the more foreign currency is spent on buying foreign seeds.

… … In this age of globalization, securing property rights to agricultural seeds is food sovereignty and food security itself.

This is why you need to know who the seeds of the lettuce that goes into salads, which are a must-have menu item at mid-priced Korean restaurants, the bell peppers used as an ingredient in japchae, and the broccoli that comes as a side dish for boiled fish come from.

--- p.261~263, from Part 6, Chapter 2, “Increased Consumption of Western Vegetables and Seed Property Rights”

The popularity of K-food overseas is the result of efforts by food and beverage manufacturers and restaurant workers since the mid-1960s to adapt foreign foods to Korean tastes.

Added to this are consumer reactions to new and unfamiliar processed foods.

During the period of compressed growth, most things, from processed foods to street food, took the path of localization, or Koreanization.

Korean processed foods and restaurant menus have been well-received by foreigners visiting Korea in the era of globalization, when Korean society has opened up to the outside world.

The popularity of K-food is also a result of the sociocultural hybridization that Korean society has embraced through compressed growth and globalization.

--- p.292~293, from “Epilogue: Reflections for the Next 100 Years”

Since the mid-1980s, several Western European countries, including the United States, have been strongly requesting the Korean government to import agricultural, livestock and fishery products.

Farmers opposed the opening of the market and demanded that the government take measures to protect agricultural, livestock and fishery products.

The power elite, who prioritized economic growth through the export of manufactured goods, perceived the agricultural sector as an obstacle to greater trade and higher growth.

In the age of globalization, Korea's food sovereignty has fallen to rock bottom.

In these difficult times, the cliché “traditional food is the best” is prevalent across government, academia, the media, and business circles.

'Food nationalism' can be a very effective strategy for recovering the property rights to agricultural, livestock and fishery products lost after the last IMF foreign exchange crisis.

However, 'closed' food nationalism is not the answer to eradicating the dark shadows cast on the Korean diet and food that have breathlessly navigated the past 100 years.

--- p.296, from “Epilogue: Reflections for the Next 100 Years”

Publisher's Review

The Globalized Taste of Koreans and the Globalization of Korean Food: A 100-Year History

─ Beyond 'Ssul' and 'Food Nationalism': A Century of Modern and Contemporary Tables

A new book by Professor Joo Young-ha, a food humanist you can trust and read!

Food humanist Joo Young-ha, who has emphasized the need for a humanistic exploration of food, saying, “If you know the history of food, you can see its society and culture,” will now focus on “the encounter between the global food system and Korean food” and trace the origins of Korean food culture in the context of world history.

With the emergence of a transnational food system along with globalization, imported ingredients and factory-made foods can be easily found in Korean supermarkets, and thanks to the global popularity of Korean food, Korean food can be found everywhere in Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

However, it is not recent that Korean food has come into contact with the global food system.

Since the late 19th century, when the country opened its doors to foreign countries, Korean food culture has been constantly influenced by the world, changing the tastes of Koreans.

This book examines the foods that served Koreans during six periods: the Korean Peninsula's opening to the world food system, colonization, war, the Cold War, compressed growth, and globalization. It traces how Koreans' tastes have evolved through encounters with the world amidst rapid changes in the times, leading to the present.

From Western-style banquets served at the Imperial Palace of the Korean Empire, to Korean and Japanese cuisine influenced by the colonial period, to the snacks created as war rations and food aid, to the instant food and restaurant industries that grew rapidly during economic growth and globalization, and even the recent K-food craze, this book vividly tells the surprising and fascinating history of how today's Korean food culture was created.

The modern and contemporary period is the period in which the foods and food cultures we are familiar with today were born, so it is true that there are many stories that emphasize interest-oriented 'stories' and traditions and stimulate nationalism.

The food humanist who wrote this book

Professor Joo Young-ha has meticulously analyzed vast amounts of historical data and has presented a reliable history of food culture based on theories and methodologies of various academic disciplines, including cultural anthropology, history, and sociology.

This book also goes beyond the 'stories' and 'food nationalism' about Korean food culture and contains stories about Korean food that readers can trust and read.

Moreover, it goes beyond simply sharing episodes about Korean food, and provides an opportunity for humanistic reflection by pointing out issues that are immediately before our eyes, such as food sovereignty, the massive factory-style agricultural and livestock industry, healthy eating, and eating habits in the pandemic era.

《A Hundred Years of Meals》 is a first-part series on the history of Korean food culture by food humanist Professor Joo Young-ha. Starting with the modern and contemporary era, it goes back in time to examine the origins and changes in today's Korean food culture.

How have Koreans' tastes and dining tables changed?

The more you learn about the history of Korean food, the more surprising and interesting it becomes.

The story of Korean food covered in this book is clearly a story from the past, yet it is familiar and friendly to us.

This shows that most of the food culture consumed by Koreans today was created over the past 100 years.

You can encounter the moments when the Korean table first met the world through the descriptions of Korean food by George Polk, a U.S. Navy sailor who enjoyed Korean food while traveling around the Korean Peninsula; the mistakes of interpreter Kim Deuk-ryeon who was first introduced to Western food; the menu of the luncheon where Emperor Gojong of the Korean Empire had his first official meal with a woman; and the stories of Son Tak and Madame Kroebel, who were appointed royal connoisseurs of the Korean Empire.

Just as the food culture of the Korean Peninsula was about to embark on a path of Westernization, Joseon came under Japanese colonial rule, and the taste buds of Joseon people also gradually became accustomed to the tastes of the empire.

The story of Japanese factory-made soy sauce, called jangyu, which is still a basic ingredient in Korean food today, Ajinomoto, a chemical seasoning that dominated Joseon's tables, and the process by which the tastes of the colonies crossed over to the empire and became Japanese foods such as 'yakiniku' and 'mentaiko' tells a new story about the relationship between the empire and the colony from the perspective of food and the food industry.

The Pacific War, the Korean War, and the subsequent Cold War that the Korean Peninsula had to endure also greatly changed Korean food culture.

In times of food shortages, substitute foods such as braised pupae appeared, as well as various snacks such as hotteok and somen made with wheat flour sent as relief and aid by the UN and the US, such as noodles, sujebi, bindaetteok, and pulppang.

The government's push to promote fast food to address food shortages has led to the creation of Korean-style ramen noodles with their signature spicy broth, spicy makgeolli, soju, a diluted version of the national drink, and even fried chicken, Korea's favorite.

The stories behind the creation of the foods that are most consumed and have become representative foods in Korea today will surprise readers.

From the story of Korea's factory-made food industry, which grew rapidly during the process of compressed growth and globalization, to the hidden stories of familiar foods and restaurants, such as the raw fish enjoyed in the 1970s, the pork belly grill and galbi restaurants that became popular in the 1980s, fast food restaurants that opened in the 1990s, and Korean restaurants where female hostesses disappeared, there is a flood of stories.

In addition, we can examine the globalized tastes of Koreans following the market opening and the IMF foreign exchange crisis, as well as the true face of Korea's food sovereignty, which has fallen to rock bottom.

This book introduces various aspects of Korean food culture through various sources, including travelogues written by Westerners traveling through Joseon, various documents including royal documents, and advertisements from newspapers and food companies.

The more you learn about this material, the more colorful and exciting the fascinating history of Korean food culture will become.

K-Food Trends and Pandemics: Where Should Korean Food Culture Go?

─Examining the history of Korean food culture and suggesting its future.

In this book, the author emphasizes that the history of food is by no means just a collection of episodes or the subject of entertainment programs.

He suggests that examining the origins and evolution of food can be a process of predicting and preparing for the future, and that we diagnose the present through the past 100 years of Korean food culture and look forward to the next 100 years together.

From the opening of its ports to globalization, Korean food has encountered and been influenced by various cultures, taking the path of Koreanization.

The author argues that it is this sociocultural hybridity of Korean food that has created today's K-food trend.

Despite this encouraging news, however, Koreans today face a dark shadow over their food and eating habits, akin to the food sovereignty issues of the globalized era, and the pandemic that may have been created by the massive multinational agricultural, livestock, and fishery industries and their value chains.

In this situation, closed-minded “food nationalism” that simply says “traditional food is the best” or banning eating together to prevent droplet infection cannot be the true answer.

Understanding our dining table over the past century offers an opportunity to deeply contemplate and reflect on the issues facing us, including food sovereignty, the global food chain, and post-pandemic eating habits, all of which surround tables not only in Korea but around the world.

─ Beyond 'Ssul' and 'Food Nationalism': A Century of Modern and Contemporary Tables

A new book by Professor Joo Young-ha, a food humanist you can trust and read!

Food humanist Joo Young-ha, who has emphasized the need for a humanistic exploration of food, saying, “If you know the history of food, you can see its society and culture,” will now focus on “the encounter between the global food system and Korean food” and trace the origins of Korean food culture in the context of world history.

With the emergence of a transnational food system along with globalization, imported ingredients and factory-made foods can be easily found in Korean supermarkets, and thanks to the global popularity of Korean food, Korean food can be found everywhere in Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

However, it is not recent that Korean food has come into contact with the global food system.

Since the late 19th century, when the country opened its doors to foreign countries, Korean food culture has been constantly influenced by the world, changing the tastes of Koreans.

This book examines the foods that served Koreans during six periods: the Korean Peninsula's opening to the world food system, colonization, war, the Cold War, compressed growth, and globalization. It traces how Koreans' tastes have evolved through encounters with the world amidst rapid changes in the times, leading to the present.

From Western-style banquets served at the Imperial Palace of the Korean Empire, to Korean and Japanese cuisine influenced by the colonial period, to the snacks created as war rations and food aid, to the instant food and restaurant industries that grew rapidly during economic growth and globalization, and even the recent K-food craze, this book vividly tells the surprising and fascinating history of how today's Korean food culture was created.

The modern and contemporary period is the period in which the foods and food cultures we are familiar with today were born, so it is true that there are many stories that emphasize interest-oriented 'stories' and traditions and stimulate nationalism.

The food humanist who wrote this book

Professor Joo Young-ha has meticulously analyzed vast amounts of historical data and has presented a reliable history of food culture based on theories and methodologies of various academic disciplines, including cultural anthropology, history, and sociology.

This book also goes beyond the 'stories' and 'food nationalism' about Korean food culture and contains stories about Korean food that readers can trust and read.

Moreover, it goes beyond simply sharing episodes about Korean food, and provides an opportunity for humanistic reflection by pointing out issues that are immediately before our eyes, such as food sovereignty, the massive factory-style agricultural and livestock industry, healthy eating, and eating habits in the pandemic era.

《A Hundred Years of Meals》 is a first-part series on the history of Korean food culture by food humanist Professor Joo Young-ha. Starting with the modern and contemporary era, it goes back in time to examine the origins and changes in today's Korean food culture.

How have Koreans' tastes and dining tables changed?

The more you learn about the history of Korean food, the more surprising and interesting it becomes.

The story of Korean food covered in this book is clearly a story from the past, yet it is familiar and friendly to us.

This shows that most of the food culture consumed by Koreans today was created over the past 100 years.

You can encounter the moments when the Korean table first met the world through the descriptions of Korean food by George Polk, a U.S. Navy sailor who enjoyed Korean food while traveling around the Korean Peninsula; the mistakes of interpreter Kim Deuk-ryeon who was first introduced to Western food; the menu of the luncheon where Emperor Gojong of the Korean Empire had his first official meal with a woman; and the stories of Son Tak and Madame Kroebel, who were appointed royal connoisseurs of the Korean Empire.

Just as the food culture of the Korean Peninsula was about to embark on a path of Westernization, Joseon came under Japanese colonial rule, and the taste buds of Joseon people also gradually became accustomed to the tastes of the empire.

The story of Japanese factory-made soy sauce, called jangyu, which is still a basic ingredient in Korean food today, Ajinomoto, a chemical seasoning that dominated Joseon's tables, and the process by which the tastes of the colonies crossed over to the empire and became Japanese foods such as 'yakiniku' and 'mentaiko' tells a new story about the relationship between the empire and the colony from the perspective of food and the food industry.

The Pacific War, the Korean War, and the subsequent Cold War that the Korean Peninsula had to endure also greatly changed Korean food culture.

In times of food shortages, substitute foods such as braised pupae appeared, as well as various snacks such as hotteok and somen made with wheat flour sent as relief and aid by the UN and the US, such as noodles, sujebi, bindaetteok, and pulppang.

The government's push to promote fast food to address food shortages has led to the creation of Korean-style ramen noodles with their signature spicy broth, spicy makgeolli, soju, a diluted version of the national drink, and even fried chicken, Korea's favorite.

The stories behind the creation of the foods that are most consumed and have become representative foods in Korea today will surprise readers.

From the story of Korea's factory-made food industry, which grew rapidly during the process of compressed growth and globalization, to the hidden stories of familiar foods and restaurants, such as the raw fish enjoyed in the 1970s, the pork belly grill and galbi restaurants that became popular in the 1980s, fast food restaurants that opened in the 1990s, and Korean restaurants where female hostesses disappeared, there is a flood of stories.

In addition, we can examine the globalized tastes of Koreans following the market opening and the IMF foreign exchange crisis, as well as the true face of Korea's food sovereignty, which has fallen to rock bottom.

This book introduces various aspects of Korean food culture through various sources, including travelogues written by Westerners traveling through Joseon, various documents including royal documents, and advertisements from newspapers and food companies.

The more you learn about this material, the more colorful and exciting the fascinating history of Korean food culture will become.

K-Food Trends and Pandemics: Where Should Korean Food Culture Go?

─Examining the history of Korean food culture and suggesting its future.

In this book, the author emphasizes that the history of food is by no means just a collection of episodes or the subject of entertainment programs.

He suggests that examining the origins and evolution of food can be a process of predicting and preparing for the future, and that we diagnose the present through the past 100 years of Korean food culture and look forward to the next 100 years together.

From the opening of its ports to globalization, Korean food has encountered and been influenced by various cultures, taking the path of Koreanization.

The author argues that it is this sociocultural hybridity of Korean food that has created today's K-food trend.

Despite this encouraging news, however, Koreans today face a dark shadow over their food and eating habits, akin to the food sovereignty issues of the globalized era, and the pandemic that may have been created by the massive multinational agricultural, livestock, and fishery industries and their value chains.

In this situation, closed-minded “food nationalism” that simply says “traditional food is the best” or banning eating together to prevent droplet infection cannot be the true answer.

Understanding our dining table over the past century offers an opportunity to deeply contemplate and reflect on the issues facing us, including food sovereignty, the global food chain, and post-pandemic eating habits, all of which surround tables not only in Korea but around the world.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: November 2, 2020

- Page count, weight, size: 352 pages | 586g | 150*220*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791160805031

- ISBN10: 1160805032

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)