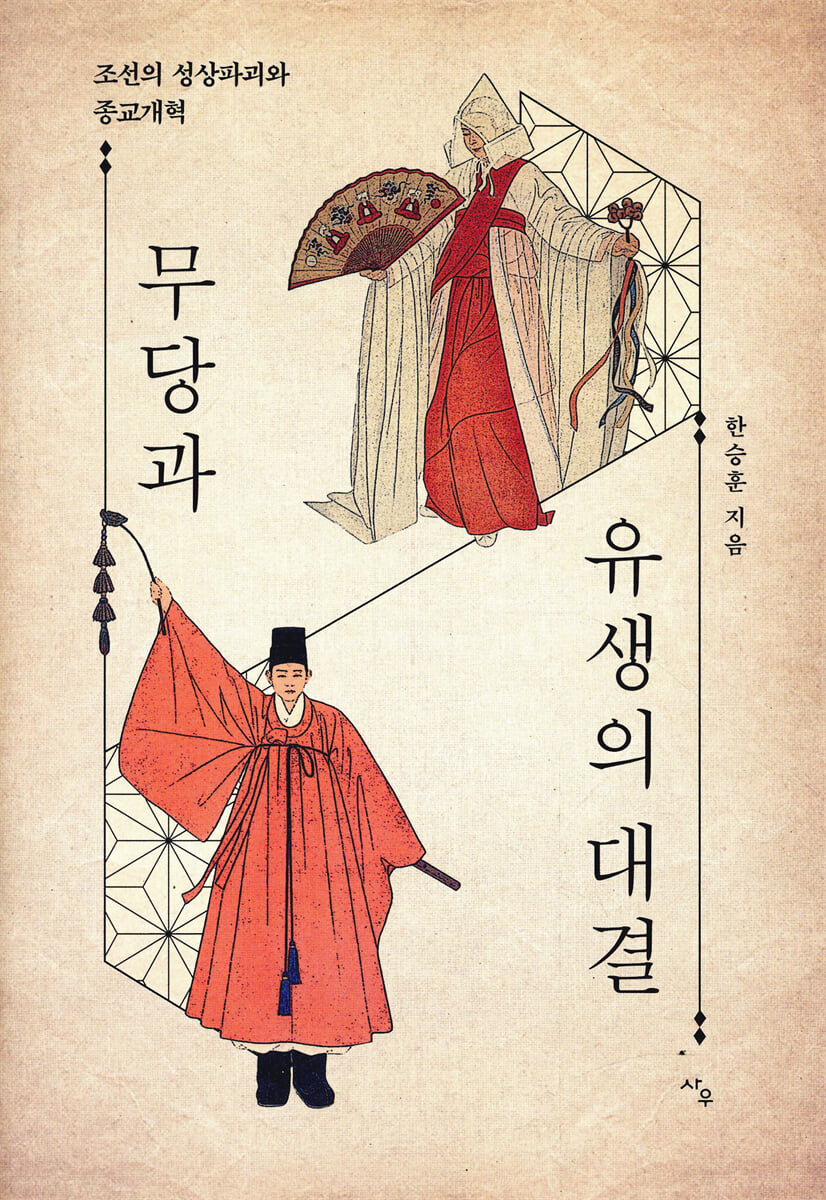

The confrontation between a shaman and a Confucian scholar

|

Description

Book Introduction

The destruction of icons and the competition surrounding gods during the Joseon Dynasty's religious reform process

This book examines the dynamic process of religious reform that unfolded over a long period of time during the Joseon Dynasty.

Joseon attempted to establish a new ruling system through Confucianism.

This project began at the founding of Joseon and continued until the dynasty's fall.

This book examines the history of religion in the Joseon Dynasty, focusing on two topics.

First, we will examine how the religion of the Goryeo Dynasty, which used abundant imagery, changed into an iconoclastic religious culture through the process of Confucianization.

What motivated the demolition of not only mountain spirits and Buddhist statues, but also statues of Confucius, revered as saints in Confucian tradition? Why was the destruction of icons more rigorous in the peripheral Joseon Dynasty than in the Ming Dynasty, the epicenter of ritual reform? To answer these questions, Part 1 meticulously examines how Confucianization in Joseon was achieved in ritual, practical, and material terms.

Part 2 examines how Confucianization and shamanism were implemented in the field of folk religion.

Although the central government succeeded in excluding shamanism from Hanyang, the ruling power of the pre-modern state could not extend beyond the capital.

In the arena of national religion, the logic of rites did not work, and criticizing it as a shamanistic act was meaningless.

In communicating with the gods and performing rituals for the dead, shamans held an overwhelming advantage.

The Confucian scholars competed fiercely to usurp the position held by the shamans.

The shaman's resistance to this was also formidable.

This confrontation continued hundreds of years later during the military regime, leading to the 'dismantling of superstitions'.

Part 2 vividly portrays the fierce confrontation between the shaman and the Confucian scholar.

This book presents the religious history of the Joseon Dynasty through a wide range of materials.

Through this book, we can not only learn about the formation and evolution of pre-modern Korean religious culture, but also grasp the foundation upon which today's Korean religious culture is formed.

This book examines the dynamic process of religious reform that unfolded over a long period of time during the Joseon Dynasty.

Joseon attempted to establish a new ruling system through Confucianism.

This project began at the founding of Joseon and continued until the dynasty's fall.

This book examines the history of religion in the Joseon Dynasty, focusing on two topics.

First, we will examine how the religion of the Goryeo Dynasty, which used abundant imagery, changed into an iconoclastic religious culture through the process of Confucianization.

What motivated the demolition of not only mountain spirits and Buddhist statues, but also statues of Confucius, revered as saints in Confucian tradition? Why was the destruction of icons more rigorous in the peripheral Joseon Dynasty than in the Ming Dynasty, the epicenter of ritual reform? To answer these questions, Part 1 meticulously examines how Confucianization in Joseon was achieved in ritual, practical, and material terms.

Part 2 examines how Confucianization and shamanism were implemented in the field of folk religion.

Although the central government succeeded in excluding shamanism from Hanyang, the ruling power of the pre-modern state could not extend beyond the capital.

In the arena of national religion, the logic of rites did not work, and criticizing it as a shamanistic act was meaningless.

In communicating with the gods and performing rituals for the dead, shamans held an overwhelming advantage.

The Confucian scholars competed fiercely to usurp the position held by the shamans.

The shaman's resistance to this was also formidable.

This confrontation continued hundreds of years later during the military regime, leading to the 'dismantling of superstitions'.

Part 2 vividly portrays the fierce confrontation between the shaman and the Confucian scholar.

This book presents the religious history of the Joseon Dynasty through a wide range of materials.

Through this book, we can not only learn about the formation and evolution of pre-modern Korean religious culture, but also grasp the foundation upon which today's Korean religious culture is formed.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

preface

Part 1: Iconoclasm and Iconoclasm in Joseon

1.

Statues on the mountain

Absence of religion and excess of religion

The 'Protestant' Landscape of Korean Religion

Consideration of religion in images

Wang Geon statue worshipped as a god

Taoist messenger sent by the emperor

The abbot who wanted to become both pope and kaiser

Do gods have families?

Standardized gods

From the gods to the gods

Confucian scholars' iconoclastic movement

The statue of the Virgin Mary destroyed by a monk

2.

The image of heresy

The royal family's Buddhist faith

You cannot bow down to a Buddha statue.

Emperor Wu of Liang and Emperor Yongle, who favored Buddhism

dried and rotten Buddha bones

The yellow face of Shakyamuni

Buddha statue causing migration

Decapitated Buddha statue

Seated Buddha statue

possessed Buddha statue

Sweating Buddha

Shinto and Buddhist statues

Iconoclasm against the new gods

bleeding crucifix

3.

Confucianism's nature

Young Kim Jong-jik and the Seongju Confucius Temple

Confucius's temple and Buddha's palace

From the wandering Confucius to the emperor

The Holy Spirit and Demons

Sosang's Confucian shrine

Shinju's Confucian shrine

The image of Confucius in Joseon as seen by Chinese envoys

100 years of dirty customs

A dignified statue of Confucius to behold

Ritual reform of the family system

Statue of Confucius buried in the ground

Part 2: The Shaman and the Confucian Scholar

4.

Confucianism's conquest of shamanism

Confucianization and Christianization

The founding of Joseon as a religious reform

Shamans performing rain rituals

National rituals to appease vengeful spirits

Two stages: official religion and folk religion

Shamans expelled from Hanyang

Shamans in the palace

Punishment for shamans

5.

A 'strange' shaman and a 'heroic' local official

The shamanic tradition that was created

From reporter to Dangun

Shamans in Confucian classics

The divine shaman and the lowly shaman

evil shamans

A police officer and a shaman

Seomunpyo model

Ham Yu-il's defeat and An Hyang's victory

The Age of Heroic Governors

Revenge of the Insulted God

6.

The struggle between the gods and the dead

Confucian scholars on the stage of folk religion

Scholars who summon ghosts

Warriors who exorcise ghosts

Ogeumjamshin and Samcheok Seonghwangshin

Heo Gyun, who accused God

The Virgin Mary of Jirisan and Kim Jong-jik

Scholars who meet gods in their dreams

Qualification to worship the ancestral gods

Between ancestral rites and rituals

Near-death experiences of scholars

Real and fake shamans

Conclusion

main

References

Part 1: Iconoclasm and Iconoclasm in Joseon

1.

Statues on the mountain

Absence of religion and excess of religion

The 'Protestant' Landscape of Korean Religion

Consideration of religion in images

Wang Geon statue worshipped as a god

Taoist messenger sent by the emperor

The abbot who wanted to become both pope and kaiser

Do gods have families?

Standardized gods

From the gods to the gods

Confucian scholars' iconoclastic movement

The statue of the Virgin Mary destroyed by a monk

2.

The image of heresy

The royal family's Buddhist faith

You cannot bow down to a Buddha statue.

Emperor Wu of Liang and Emperor Yongle, who favored Buddhism

dried and rotten Buddha bones

The yellow face of Shakyamuni

Buddha statue causing migration

Decapitated Buddha statue

Seated Buddha statue

possessed Buddha statue

Sweating Buddha

Shinto and Buddhist statues

Iconoclasm against the new gods

bleeding crucifix

3.

Confucianism's nature

Young Kim Jong-jik and the Seongju Confucius Temple

Confucius's temple and Buddha's palace

From the wandering Confucius to the emperor

The Holy Spirit and Demons

Sosang's Confucian shrine

Shinju's Confucian shrine

The image of Confucius in Joseon as seen by Chinese envoys

100 years of dirty customs

A dignified statue of Confucius to behold

Ritual reform of the family system

Statue of Confucius buried in the ground

Part 2: The Shaman and the Confucian Scholar

4.

Confucianism's conquest of shamanism

Confucianization and Christianization

The founding of Joseon as a religious reform

Shamans performing rain rituals

National rituals to appease vengeful spirits

Two stages: official religion and folk religion

Shamans expelled from Hanyang

Shamans in the palace

Punishment for shamans

5.

A 'strange' shaman and a 'heroic' local official

The shamanic tradition that was created

From reporter to Dangun

Shamans in Confucian classics

The divine shaman and the lowly shaman

evil shamans

A police officer and a shaman

Seomunpyo model

Ham Yu-il's defeat and An Hyang's victory

The Age of Heroic Governors

Revenge of the Insulted God

6.

The struggle between the gods and the dead

Confucian scholars on the stage of folk religion

Scholars who summon ghosts

Warriors who exorcise ghosts

Ogeumjamshin and Samcheok Seonghwangshin

Heo Gyun, who accused God

The Virgin Mary of Jirisan and Kim Jong-jik

Scholars who meet gods in their dreams

Qualification to worship the ancestral gods

Between ancestral rites and rituals

Near-death experiences of scholars

Real and fake shamans

Conclusion

main

References

Into the book

King Taejong's refusal to bow to a Buddhist statue was remembered as an incident that declared Joseon to be a country that did not believe in Buddhism.

It was a conception of a very unique system.

Dynasties in China, the Korean Peninsula, Vietnam, and other countries generally included all three religions—Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism—in the category of official religions.

Although the power of each tradition weakened or strengthened depending on the tastes and policies of individual monarchs, Joseon was building a national system that worshipped only Confucianism.

--- p.71

Filial piety was an important justification for maintaining royal Buddhist worship.

Royal women were generally deeply religious, and even kings who considered themselves Confucianists actively introduced Buddhist rituals to their parents' funerals.

Compared to the Confucian tradition, Buddhism excelled at the function of guiding the dead to heaven.

--- p.96

The tragedy of early Korean Catholicism was that Christianity was introduced in earnest after this situation had developed in China.

Joseon believers, who had accepted Catholicism on their own while studying Western learning without the guidance of missionaries, began to worry about the issue of ancestral rites only in the late 18th century.

After the Jesuits in China were disbanded, the missionaries who remained in Qing were those who strongly prohibited Confucian ancestral rites.

In the end, in Joseon, there were people who abandoned Catholicism in order to observe ancestral rites, and people who tried to preserve their faith even by removing ancestral tablets.

--- p.101

Confucius was a man who wandered the world without even obtaining a stable official position, let alone becoming the emperor.

Why was he, who was like that, an object of worship in the temple, in the form of an emperor?

--- p.111

From a religious historical perspective, the founding of Joseon was also the beginning of Confucianization through Neo-Confucianism.

The signal flare was 『Bulssi Japbyeon (佛氏雜辨)』 written by Jeong Do-jeon.

Even before this, there was a wariness among Confucian scholars about the indiscriminate construction of Buddhist temples and political intervention.

However, Jeong Do-jeon's criticism went far beyond that level.

He denied the worldview, cosmology, metaphysics, self-cultivation, anthropology, and morality of Buddhism and attempted to replace them with strict Confucianism.

What made this possible was the confidence of the intellectuals who accepted Neo-Confucianism.

Song Dynasty Neo-Confucianism was an attempt to complete the religious worldview, which was relatively lacking compared to Confucianism or Taoism, into a self-contained system.

It was the optimal ideology for building a new nation free from the influence of the Goryeo Dynasty and the Yuan Dynasty.

--- p.155

No Buddhist temples were built in the new capital.

Instead, spaces for Confucian rituals were systematically arranged.

Monks and shamans were banished from the city.

However, this does not mean that all of this happened in an instant.

The resistance of customs and culture was formidable.

In the royal capital Hanyang, the 'conquest' was completed relatively quickly.

But even if one took just one step out of the city walls, the ruling power seemed to lose its strength in an instant.

Vast tracts of land beyond the mountains and rivers also remained unconquered.

Ultimately, Confucianization was not completed for hundreds of years, even until the day the dynasty fell.

--- p.156

The Confucian state of Joseon's rain-making ritual involved kings and officials bowing to the gods of the capital city, children banging on jars containing lizards, shamans desperately crying out to the gods under the hot sun, and monks gathering in temples to pray.

Although this was far from the ideal of Neo-Confucianism in any sense, it was maintained until the mid-Joseon period because there was no suitable alternative.

--- p.161

Legally, even shamans were prohibited from entering the city walls.

But in reality, there were shamans who entered the palace and worked there.

In particular, women in the royal court openly invited shamans to perform prayers.

Among them were people called national shamans, or national shamans.

--- p.172

Shamanism, viewed from the perspective of a remnant of ancient national culture, is a 'created tradition' like the nation itself.

It is a fiction that the original form of shamanism existed in its complete form in the distant past, and it is also a story that has been reconstructed today that it has gone through repeated corruption and decline to become the base form it is today.

Rather than choosing whether or not to believe these fictions, we should examine why and in what era such discourses emerged and became popular.

--- p.188

'Attracting happiness and keeping disasters away [祈福禳災]' is a general goal of religions, from primitive religions to new religions that have emerged in modern times.

So, the reason Korean religion seems to be in turmoil is not due to the influence of shamanism.

Rather, things like philosophical doctrines and ethical teachings are closer to 'decoration' than the 'essence' of religion.

Because it lacks such institutional 'decoration,' shamanism is vulnerable to external attacks.

--- p.198

The scholars are communicating with ghosts 'like shamans'.

However, unlike the shaman who generally 'welcomes' and 'appeases' ghosts, the way scholars deal with ghosts is much more violent and authoritarian.

The art of dealing with ghosts was something that only scholars in the field could do, not those in government positions.

But they suppressed the ghosts with authority and majesty, like officials.

--- p.221

Like shamans, Confucian scholars could communicate with gods or the dead through dreams.

Even the disasters caused by the mountain god and the plagues spread by the demon mama that even shamans could not control could be controlled.

The people who could most directly contact the ancestral spirits were the descendants who had inherited their energy.

But we should not be fooled by these declarations.

All these stories were written by Yuja.

That's not reality.

The Confucian scholar believed that he could not only completely replace the role of the shaman, but also serve the gods and ancestors much better than the shaman.

However, there is no evidence that this kind of thinking received widespread public approval at the time.

Rather, another story that contrasts with this appears in the historical data.

The claim is that ancestral gods would prefer a shaman's ritual over a Confucian rite.

--- p.242

In the arena of folk religion, both Confucian scholars and shamans were merely religious specialists competing for the leadership of rituals and spiritual authority.

Under these conditions, Confucian scholars had an advantage in social status and authority, while shamans had a more familiar and suitable system for satisfying the religious sentiments and needs of the general public.

As a result, Confucianism's control over rituals for local gods such as Seonghwang and Sansin, which were incorporated into the national ritual system and thus easily penetrated by Confucianism, grew.

However, the shaman's dominance in access to the spirits of the dead and the world of the dead remained.

In the end, Joseon was unable to complete 'Confucianization' on the stage of folk religion until the very last moment.

It was a conception of a very unique system.

Dynasties in China, the Korean Peninsula, Vietnam, and other countries generally included all three religions—Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism—in the category of official religions.

Although the power of each tradition weakened or strengthened depending on the tastes and policies of individual monarchs, Joseon was building a national system that worshipped only Confucianism.

--- p.71

Filial piety was an important justification for maintaining royal Buddhist worship.

Royal women were generally deeply religious, and even kings who considered themselves Confucianists actively introduced Buddhist rituals to their parents' funerals.

Compared to the Confucian tradition, Buddhism excelled at the function of guiding the dead to heaven.

--- p.96

The tragedy of early Korean Catholicism was that Christianity was introduced in earnest after this situation had developed in China.

Joseon believers, who had accepted Catholicism on their own while studying Western learning without the guidance of missionaries, began to worry about the issue of ancestral rites only in the late 18th century.

After the Jesuits in China were disbanded, the missionaries who remained in Qing were those who strongly prohibited Confucian ancestral rites.

In the end, in Joseon, there were people who abandoned Catholicism in order to observe ancestral rites, and people who tried to preserve their faith even by removing ancestral tablets.

--- p.101

Confucius was a man who wandered the world without even obtaining a stable official position, let alone becoming the emperor.

Why was he, who was like that, an object of worship in the temple, in the form of an emperor?

--- p.111

From a religious historical perspective, the founding of Joseon was also the beginning of Confucianization through Neo-Confucianism.

The signal flare was 『Bulssi Japbyeon (佛氏雜辨)』 written by Jeong Do-jeon.

Even before this, there was a wariness among Confucian scholars about the indiscriminate construction of Buddhist temples and political intervention.

However, Jeong Do-jeon's criticism went far beyond that level.

He denied the worldview, cosmology, metaphysics, self-cultivation, anthropology, and morality of Buddhism and attempted to replace them with strict Confucianism.

What made this possible was the confidence of the intellectuals who accepted Neo-Confucianism.

Song Dynasty Neo-Confucianism was an attempt to complete the religious worldview, which was relatively lacking compared to Confucianism or Taoism, into a self-contained system.

It was the optimal ideology for building a new nation free from the influence of the Goryeo Dynasty and the Yuan Dynasty.

--- p.155

No Buddhist temples were built in the new capital.

Instead, spaces for Confucian rituals were systematically arranged.

Monks and shamans were banished from the city.

However, this does not mean that all of this happened in an instant.

The resistance of customs and culture was formidable.

In the royal capital Hanyang, the 'conquest' was completed relatively quickly.

But even if one took just one step out of the city walls, the ruling power seemed to lose its strength in an instant.

Vast tracts of land beyond the mountains and rivers also remained unconquered.

Ultimately, Confucianization was not completed for hundreds of years, even until the day the dynasty fell.

--- p.156

The Confucian state of Joseon's rain-making ritual involved kings and officials bowing to the gods of the capital city, children banging on jars containing lizards, shamans desperately crying out to the gods under the hot sun, and monks gathering in temples to pray.

Although this was far from the ideal of Neo-Confucianism in any sense, it was maintained until the mid-Joseon period because there was no suitable alternative.

--- p.161

Legally, even shamans were prohibited from entering the city walls.

But in reality, there were shamans who entered the palace and worked there.

In particular, women in the royal court openly invited shamans to perform prayers.

Among them were people called national shamans, or national shamans.

--- p.172

Shamanism, viewed from the perspective of a remnant of ancient national culture, is a 'created tradition' like the nation itself.

It is a fiction that the original form of shamanism existed in its complete form in the distant past, and it is also a story that has been reconstructed today that it has gone through repeated corruption and decline to become the base form it is today.

Rather than choosing whether or not to believe these fictions, we should examine why and in what era such discourses emerged and became popular.

--- p.188

'Attracting happiness and keeping disasters away [祈福禳災]' is a general goal of religions, from primitive religions to new religions that have emerged in modern times.

So, the reason Korean religion seems to be in turmoil is not due to the influence of shamanism.

Rather, things like philosophical doctrines and ethical teachings are closer to 'decoration' than the 'essence' of religion.

Because it lacks such institutional 'decoration,' shamanism is vulnerable to external attacks.

--- p.198

The scholars are communicating with ghosts 'like shamans'.

However, unlike the shaman who generally 'welcomes' and 'appeases' ghosts, the way scholars deal with ghosts is much more violent and authoritarian.

The art of dealing with ghosts was something that only scholars in the field could do, not those in government positions.

But they suppressed the ghosts with authority and majesty, like officials.

--- p.221

Like shamans, Confucian scholars could communicate with gods or the dead through dreams.

Even the disasters caused by the mountain god and the plagues spread by the demon mama that even shamans could not control could be controlled.

The people who could most directly contact the ancestral spirits were the descendants who had inherited their energy.

But we should not be fooled by these declarations.

All these stories were written by Yuja.

That's not reality.

The Confucian scholar believed that he could not only completely replace the role of the shaman, but also serve the gods and ancestors much better than the shaman.

However, there is no evidence that this kind of thinking received widespread public approval at the time.

Rather, another story that contrasts with this appears in the historical data.

The claim is that ancestral gods would prefer a shaman's ritual over a Confucian rite.

--- p.242

In the arena of folk religion, both Confucian scholars and shamans were merely religious specialists competing for the leadership of rituals and spiritual authority.

Under these conditions, Confucian scholars had an advantage in social status and authority, while shamans had a more familiar and suitable system for satisfying the religious sentiments and needs of the general public.

As a result, Confucianism's control over rituals for local gods such as Seonghwang and Sansin, which were incorporated into the national ritual system and thus easily penetrated by Confucianism, grew.

However, the shaman's dominance in access to the spirits of the dead and the world of the dead remained.

In the end, Joseon was unable to complete 'Confucianization' on the stage of folk religion until the very last moment.

--- p.251

Publisher's Review

Is authoritarianism due to Confucianism, and is shamanism due to shamanism?

The oppression and resistance that occurred during the Confucianization process in Joseon,

Exploring the background of the dual structure of Confucianism and Shamanism

Joseon's religious reform and iconoclasm that began with the founding of the nation

It is often said that Korea's institutional religion has the characteristics of 'Confucian' authoritarianism and 'shamanistic' fortune-telling.

The patriarchal religious culture that reveres pastors and monks is said to be due to Confucianism, and the sight of people praying for success in front of schools where the college entrance exam is administered is said to be due to the influence of shamanism.

Is that really true? The author explains that this perspective is based on a reversed causal relationship.

The appearance of Korean religious culture today is not a remnant of tradition.

So, what historical process did Korean religious culture go through to become what it is today?

This book examines the dynamic process of religious reform that unfolded over a long period of time during the Joseon Dynasty.

Joseon attempted to establish a new ruling system through Confucianism.

This project began at the founding of Joseon and continued until the dynasty's fall.

The author calls this process, which took place across all areas of politics, ideology, society, and culture, Confucianization.

Confucianization is the corresponding expression for Christianization in Europe.

Christianization is the process of conquering heresy and paganism that rejected Christianity.

A long and violent process, including witch hunts and the Inquisition, was carried out to convert pagan monarchs and Christianize individuals.

Confucianism, unlike Christianity, did not force conversion or exclusive affiliation.

While claiming to be a Confucian scholar, he was able to maintain a balance between Buddhist and Taoist rituals and practices.

However, the situation changed when Song Dynasty's Neo-Confucianism entered the Korean Peninsula.

While Confucianism focused on the institutions and ritual systems of the state, Neo-Confucianism greatly expanded its scope to include self-cultivation and cosmology, which were the domains of Buddhism and Taoism.

Now, Yuja could reach the state of a saint through practice without having to borrow the systems of Buddhism or Taoism.

Confucian scholars in the late Goryeo and early Joseon Dynasties began to have an identity that was distinctly different from that of the past.

From the perspective of religious history, the founding of Joseon was also the beginning of Confucianization through Neo-Confucianism.

In this book, the author looks at the meaning of Confucianism from a slightly different angle.

Confucianization was closer to a religious reform that sought to reform not only ideological and institutional issues but also the entire culture.

Why did Confucian scholars in Joseon, a Confucian country, destroy statues of Confucius?

Confucianization took place in two different ways on two stages: official religion and folk religion.

In Part 1, we explore how the religion of the Goryeo Dynasty, which used rich imagery, transformed into an iconoclastic religious culture through the process of Confucianization.

Until the early Joseon Dynasty, statues of mountain gods and city gods were made of clay, wood, or metal.

God also has a family, so they make a statue of him and worship him together and perform sacrifices.

There were such shrines all over the country.

But these days, it is difficult to find places or ceremonies like this.

This is because the dwellings of the gods, which were filled with images throughout most of the Joseon Dynasty, were destroyed or replaced with other things.

Confucian scholars also rejected Buddhism.

You may personally like Buddhism, and your family may have continued Buddhist rituals.

However, there should not be any Buddhist statues in the palaces of Confucian countries.

“By the 16th century, Confucian scholars were destroying Buddhist statues, burning down shrines, and throwing away statues of gods.

The result of iconoclasm was the demolition of the statue of Confucius, the most sacred object of Confucianism.

The historic statues of Confucius that remained in Kaesong and Pyongyang were removed by the state.

The logic was that serving the gods was like Buddhism, and that it was a barbarian custom.”

What motivated the demolition of not only mountain spirits and Buddhist statues, but also statues of Confucius, revered as saints in Confucian tradition? Why was the destruction of icons more rigorous in the peripheral Joseon Dynasty than in the Ming Dynasty, the epicenter of ritual reform? To answer these questions, Part 1 meticulously examines how Confucianization in Joseon was achieved in ritual, practical, and material terms.

Another goal of Confucianism was to eradicate shamanism.

First of all, shamans were excluded from official state ceremonies.

And the shaman was banished from Hanyang.

However, when problems such as drought or illness of the royal family occurred, they had to rely on shamans.

Completely excluding shamanism from the institutional sphere was not easy.

Eventually, by the late Joseon Dynasty, most shamanistic elements had disappeared from the official religious sphere.

Finally, Confucianism came to dominate the official religion.

Who is better at dealing with ghosts?

A tense confrontation between a shaman and a scholar surrounding the gods and the dead

Part 2 examines how Confucianization and shamanism were implemented in the field of folk religion.

Confucian scholars considered shamans to be shallow and uncivilized beings who practiced sorcery and deceived the people.

Although shamanism was excluded and banished from the official religious sphere, Confucianism and shamanism coexisted for a while.

Shamanism existed only to a limited extent, to the extent of mobilizing shamans for rain-making rituals during severe droughts.

As Confucian examples were refined, shamanistic elements were gradually banished.

The situation in the folk religion field during the same period was different.

Although the central government succeeded in excluding shamanism from Hanyang, the ruling power of the pre-modern state could not extend beyond the capital.

The suppression of shamanism in the provinces was led by local officials and local noble families.

The Confucian scholars sought to strengthen their cultural dominance in the region.

However, this area was dominated by folk religious experts such as shamans and sorcerers.

It was right here that the fierce competition took place.

The lords had no legal or physical power of compulsion.

Since neither side was overwhelmingly superior, it lasted much longer and more tediously than the Confucianization that took place on the official religious stage.

“The way local officials broke away from shamanism was qualitatively different from the discussions taking place in the court.

The general way of dealing with shamanism in the institutional arena of discussion was to weigh the right path and the right way through the scriptures and past precedents.

However, in situations where local officials are trying to persuade local residents, this kind of theoretical and prescriptive discussion rarely takes place.

What stands out is the display of power.

The more bold, swift, and violent the overthrow of shamanism, the more likely it was to succeed.

The fact that the officials who committed such blasphemies did not suffer the vengeance of ghosts was clear evidence that their power was superior to that of the shamans' ghosts.”

In the arena of national religion, the logic of rites did not work, and criticizing it as a shamanistic act was meaningless.

In communicating with the gods and performing rituals for the dead, shamans held an overwhelming advantage.

The Confucian scholars competed fiercely to usurp the position held by the shamans.

The shaman's resistance to this was also formidable.

Confucian scholars attempted to abolish shamanism, but in the lives of the common people, shamanism played a religious role that Confucianism could not replace.

This created a unique Korean religious culture structure of dual Confucianism and shamanism.

Part 2 vividly portrays the fierce confrontation between the shaman and the Confucian scholar.

This book presents the religious history of the Joseon Dynasty through a wide range of materials.

Through this book, we can not only learn about the formation and evolution of pre-modern Korean religious culture, but also understand the foundation upon which today's Korean religious culture is formed.

The oppression and resistance that occurred during the Confucianization process in Joseon,

Exploring the background of the dual structure of Confucianism and Shamanism

Joseon's religious reform and iconoclasm that began with the founding of the nation

It is often said that Korea's institutional religion has the characteristics of 'Confucian' authoritarianism and 'shamanistic' fortune-telling.

The patriarchal religious culture that reveres pastors and monks is said to be due to Confucianism, and the sight of people praying for success in front of schools where the college entrance exam is administered is said to be due to the influence of shamanism.

Is that really true? The author explains that this perspective is based on a reversed causal relationship.

The appearance of Korean religious culture today is not a remnant of tradition.

So, what historical process did Korean religious culture go through to become what it is today?

This book examines the dynamic process of religious reform that unfolded over a long period of time during the Joseon Dynasty.

Joseon attempted to establish a new ruling system through Confucianism.

This project began at the founding of Joseon and continued until the dynasty's fall.

The author calls this process, which took place across all areas of politics, ideology, society, and culture, Confucianization.

Confucianization is the corresponding expression for Christianization in Europe.

Christianization is the process of conquering heresy and paganism that rejected Christianity.

A long and violent process, including witch hunts and the Inquisition, was carried out to convert pagan monarchs and Christianize individuals.

Confucianism, unlike Christianity, did not force conversion or exclusive affiliation.

While claiming to be a Confucian scholar, he was able to maintain a balance between Buddhist and Taoist rituals and practices.

However, the situation changed when Song Dynasty's Neo-Confucianism entered the Korean Peninsula.

While Confucianism focused on the institutions and ritual systems of the state, Neo-Confucianism greatly expanded its scope to include self-cultivation and cosmology, which were the domains of Buddhism and Taoism.

Now, Yuja could reach the state of a saint through practice without having to borrow the systems of Buddhism or Taoism.

Confucian scholars in the late Goryeo and early Joseon Dynasties began to have an identity that was distinctly different from that of the past.

From the perspective of religious history, the founding of Joseon was also the beginning of Confucianization through Neo-Confucianism.

In this book, the author looks at the meaning of Confucianism from a slightly different angle.

Confucianization was closer to a religious reform that sought to reform not only ideological and institutional issues but also the entire culture.

Why did Confucian scholars in Joseon, a Confucian country, destroy statues of Confucius?

Confucianization took place in two different ways on two stages: official religion and folk religion.

In Part 1, we explore how the religion of the Goryeo Dynasty, which used rich imagery, transformed into an iconoclastic religious culture through the process of Confucianization.

Until the early Joseon Dynasty, statues of mountain gods and city gods were made of clay, wood, or metal.

God also has a family, so they make a statue of him and worship him together and perform sacrifices.

There were such shrines all over the country.

But these days, it is difficult to find places or ceremonies like this.

This is because the dwellings of the gods, which were filled with images throughout most of the Joseon Dynasty, were destroyed or replaced with other things.

Confucian scholars also rejected Buddhism.

You may personally like Buddhism, and your family may have continued Buddhist rituals.

However, there should not be any Buddhist statues in the palaces of Confucian countries.

“By the 16th century, Confucian scholars were destroying Buddhist statues, burning down shrines, and throwing away statues of gods.

The result of iconoclasm was the demolition of the statue of Confucius, the most sacred object of Confucianism.

The historic statues of Confucius that remained in Kaesong and Pyongyang were removed by the state.

The logic was that serving the gods was like Buddhism, and that it was a barbarian custom.”

What motivated the demolition of not only mountain spirits and Buddhist statues, but also statues of Confucius, revered as saints in Confucian tradition? Why was the destruction of icons more rigorous in the peripheral Joseon Dynasty than in the Ming Dynasty, the epicenter of ritual reform? To answer these questions, Part 1 meticulously examines how Confucianization in Joseon was achieved in ritual, practical, and material terms.

Another goal of Confucianism was to eradicate shamanism.

First of all, shamans were excluded from official state ceremonies.

And the shaman was banished from Hanyang.

However, when problems such as drought or illness of the royal family occurred, they had to rely on shamans.

Completely excluding shamanism from the institutional sphere was not easy.

Eventually, by the late Joseon Dynasty, most shamanistic elements had disappeared from the official religious sphere.

Finally, Confucianism came to dominate the official religion.

Who is better at dealing with ghosts?

A tense confrontation between a shaman and a scholar surrounding the gods and the dead

Part 2 examines how Confucianization and shamanism were implemented in the field of folk religion.

Confucian scholars considered shamans to be shallow and uncivilized beings who practiced sorcery and deceived the people.

Although shamanism was excluded and banished from the official religious sphere, Confucianism and shamanism coexisted for a while.

Shamanism existed only to a limited extent, to the extent of mobilizing shamans for rain-making rituals during severe droughts.

As Confucian examples were refined, shamanistic elements were gradually banished.

The situation in the folk religion field during the same period was different.

Although the central government succeeded in excluding shamanism from Hanyang, the ruling power of the pre-modern state could not extend beyond the capital.

The suppression of shamanism in the provinces was led by local officials and local noble families.

The Confucian scholars sought to strengthen their cultural dominance in the region.

However, this area was dominated by folk religious experts such as shamans and sorcerers.

It was right here that the fierce competition took place.

The lords had no legal or physical power of compulsion.

Since neither side was overwhelmingly superior, it lasted much longer and more tediously than the Confucianization that took place on the official religious stage.

“The way local officials broke away from shamanism was qualitatively different from the discussions taking place in the court.

The general way of dealing with shamanism in the institutional arena of discussion was to weigh the right path and the right way through the scriptures and past precedents.

However, in situations where local officials are trying to persuade local residents, this kind of theoretical and prescriptive discussion rarely takes place.

What stands out is the display of power.

The more bold, swift, and violent the overthrow of shamanism, the more likely it was to succeed.

The fact that the officials who committed such blasphemies did not suffer the vengeance of ghosts was clear evidence that their power was superior to that of the shamans' ghosts.”

In the arena of national religion, the logic of rites did not work, and criticizing it as a shamanistic act was meaningless.

In communicating with the gods and performing rituals for the dead, shamans held an overwhelming advantage.

The Confucian scholars competed fiercely to usurp the position held by the shamans.

The shaman's resistance to this was also formidable.

Confucian scholars attempted to abolish shamanism, but in the lives of the common people, shamanism played a religious role that Confucianism could not replace.

This created a unique Korean religious culture structure of dual Confucianism and shamanism.

Part 2 vividly portrays the fierce confrontation between the shaman and the Confucian scholar.

This book presents the religious history of the Joseon Dynasty through a wide range of materials.

Through this book, we can not only learn about the formation and evolution of pre-modern Korean religious culture, but also understand the foundation upon which today's Korean religious culture is formed.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Publication date: January 27, 2021

- Page count, weight, size: 280 pages | 434g | 152*224*20mm

- ISBN13: 9791187332619

- ISBN10: 1187332615

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)