Red Hunger

|

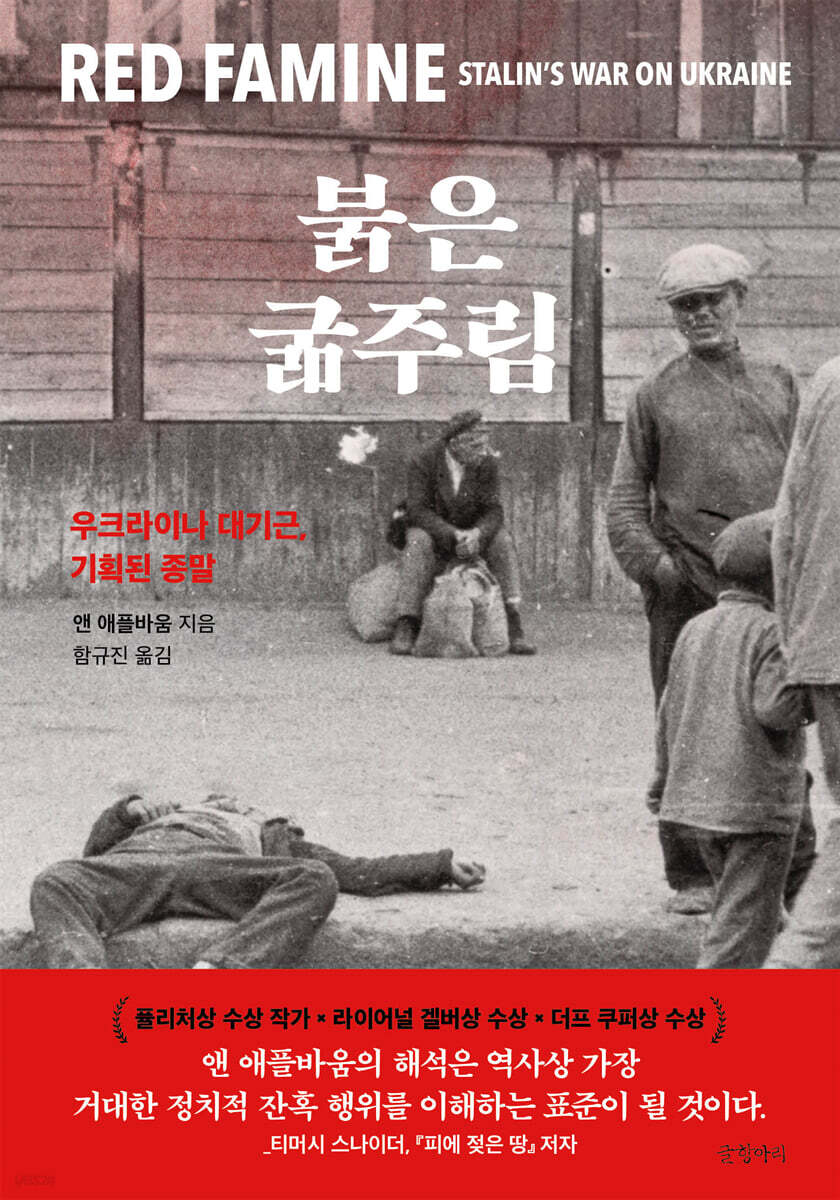

Description

Book Introduction

We, the witnesses of destruction,

What kind of historical sense will be embodied?

Anne Applebaum's interpretation is the most

It will become the standard by which we understand massive political atrocities.

Timothy Snyder, author of Blood-Soaked Soil

What chain of events led to the disaster?

What other emotions organize the genocide of a nation?

A starving human body first consumes glucose stored in the body and then burns fat.

This process lasts several weeks and during this time the body's tissues rapidly weaken.

Soon after, the body breaks down its own proteins and eats away at tissues and muscles.

The skin becomes thinner and the eyes bulge out.

The unbalanced accumulation of moisture replaces the bloated stomach, causing the stomach to swell.

Various diseases that hasten death strike in no particular order.

But up to this point, it is only a hunger of the flesh.

A Ukrainian famine survivor says hunger “ruined his soul.”

Hunger stops thinking.

They say that before they starved, they even remembered losing one of their earrings, but after their stomachs were empty, their memories became hazy, like a fog.

Even fear and sadness become dull.

I stared at the corpses strewn across the street as if they were objects, and all I could think about was that I was hungry.

It is nonsense to distinguish between the physical and the mental when such extreme harm is being done to the body.

And Stalin knew this too.

Stalin's politics were thoroughly death politics, and there could not have been a more effective means of deciding who to kill than the confiscation of grain.

In other words, hunger was an excellent means of eliminating Ukraine in one fell swoop, both materially and spiritually.

Hunger engulfed the Ukrainian people.

“The richest land in the world, the harvest is taken from the hands of those who till it, and the grain is exported to supplement the national treasury, while the farmers are left to starve.

The policy's effectiveness was clear.

“In the midst of hellish hunger, Ukrainians (…) became obedient socialist proletarians.”

The Ukrainian famine caused by Stalin was the worst famine in European history, and it was a war started by the Soviet Union wielding food as a weapon against its own people.

In the early spring of 1932, secret police officers throughout the Soviet Union were writing reports and letters.

If I were to write down the reality that unfolded before my eyes, it would be hell.

Children were starving, their bellies were swollen, train stations were teeming with refugees, and corpses were strewn across the streets.

Those who had seen hell made desperate appeals to party officials.

But it was a cry that went unanswered, not properly conveyed anywhere.

The famine of 1932-1933 was a thoroughly planned civil war.

War politicizes every context and strategically redeploys every means.

Stalin politicized the very identity of the Ukrainian people and meticulously planned the destruction of a nation by selectively distributing confiscated food.

The Marxist economic view he espoused distorted the existence of peasants.

Peasants deserved to be sacrificed for the industrialization of the Soviet Union, and therefore their land and grain should be donated to the state.

In particular, the wealthy peasants, the 'kulaks', who owned private property, were no different from class enemies and had to be purged first.

Only farm collectivization and communal farm reform could lead to true proletarian transformation.

Stalin's obsessive belief, though dressed up in the language of 'revolution', amounted to colonizing his own people, and the disastrous results were proof of this.

“Russians moved into the empty houses where the owners starved to death or fled, weakening Ukraine’s national identity.

Stalin, who persistently pushed forward this brutal policy and purged revolutionary comrades who opposed it by labeling them reactionaries, seized absolute power and held a 'victors' congress'.

“It was January 1934, after four million Ukrainians had died.”

Ukraine is not alone in suffering from famine.

Especially in Russia's Volga region, countless people starved due to Stalin's indiscriminate grain confiscation orders, no less than in Ukraine.

Evidence of famine damage throughout the Soviet Union has reduced Ukraine to a laughing stock, exaggerating its own losses.

However, Applebaum, quoting historian Andrea Graziosi, points out that “no one confuses the general history of ‘Nazi atrocities’ with the very specific story of Hitler’s genocide of Jews and Gypsies.”

If the famine that swept across the Soviet Union was a major strand of history, Ukraine's special situation is a branch branching off from it.

And to get closer to the truth through history, we must pave the way for more stems to spread out like leaf veins.

This is also the perspective that Anne Applebaum presents in this book, and it is also here that we can understand why she gave the book the subtitle, 'Stalin's War in Ukraine.'

Soviet historian Sheila Fitzpatrick discusses the question of "intention," arguing that Stalin's intention was not to kill millions, but to obtain as much grain as possible.

However, he acknowledges Applebaum's argument as a legitimate difference of interpretation, and furthermore, he believes that Applebaum's book not only exposes the political and academic impulse to downplay the Soviet famine, but also provides historians with interesting insights by examining how Ukraine exploited the issue after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Applebaum synthesizes correspondence between Stalin and his entourage, secret police reports, and various documents handed down to local party officials to uncover Stalin's ambition to exterminate the Ukrainian people, a thorn in Russia's side.

Russia never recognized Ukraine as a sovereign state in the first place.

Since the time of the Russian Empire, Ukraine has been considered a remote village of Russia.

Ukrainian was nothing more than a dialect of Russian, and Ukrainians were an ignorant and uncivilized people, little more than former serfs.

But no matter how the surrounding powers defined Ukraine, a unique national identity emerged in this land.

That is why, when the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917, Ukraine finally felt that its opportunity had come to establish its own sovereign state.

The demonstrations that took place in Kiev on April 1st of that year became a nightmare for the Soviet Union and continued to make Stalin anxious.

Ukrainian people and peasants were almost synonymous.

This is because the nationalist movement began with the restoration of the Ukrainian language and culture, which were usually found only in rural areas.

Thus, Stalin's deep-rooted distrust and contempt for the peasantry was part of a paranoia that, along with the problem of revolutionary ideology, he would crush any remnant of national identity that might pose a threat to Russia.

Applebaum analyzes the material he has gathered to trace the path this madness took, leading to frenzied grain plunder, confiscations, extraordinary measures, mass purges, the Gulag, and the Holodomor.

What kind of historical sense will be embodied?

Anne Applebaum's interpretation is the most

It will become the standard by which we understand massive political atrocities.

Timothy Snyder, author of Blood-Soaked Soil

What chain of events led to the disaster?

What other emotions organize the genocide of a nation?

A starving human body first consumes glucose stored in the body and then burns fat.

This process lasts several weeks and during this time the body's tissues rapidly weaken.

Soon after, the body breaks down its own proteins and eats away at tissues and muscles.

The skin becomes thinner and the eyes bulge out.

The unbalanced accumulation of moisture replaces the bloated stomach, causing the stomach to swell.

Various diseases that hasten death strike in no particular order.

But up to this point, it is only a hunger of the flesh.

A Ukrainian famine survivor says hunger “ruined his soul.”

Hunger stops thinking.

They say that before they starved, they even remembered losing one of their earrings, but after their stomachs were empty, their memories became hazy, like a fog.

Even fear and sadness become dull.

I stared at the corpses strewn across the street as if they were objects, and all I could think about was that I was hungry.

It is nonsense to distinguish between the physical and the mental when such extreme harm is being done to the body.

And Stalin knew this too.

Stalin's politics were thoroughly death politics, and there could not have been a more effective means of deciding who to kill than the confiscation of grain.

In other words, hunger was an excellent means of eliminating Ukraine in one fell swoop, both materially and spiritually.

Hunger engulfed the Ukrainian people.

“The richest land in the world, the harvest is taken from the hands of those who till it, and the grain is exported to supplement the national treasury, while the farmers are left to starve.

The policy's effectiveness was clear.

“In the midst of hellish hunger, Ukrainians (…) became obedient socialist proletarians.”

The Ukrainian famine caused by Stalin was the worst famine in European history, and it was a war started by the Soviet Union wielding food as a weapon against its own people.

In the early spring of 1932, secret police officers throughout the Soviet Union were writing reports and letters.

If I were to write down the reality that unfolded before my eyes, it would be hell.

Children were starving, their bellies were swollen, train stations were teeming with refugees, and corpses were strewn across the streets.

Those who had seen hell made desperate appeals to party officials.

But it was a cry that went unanswered, not properly conveyed anywhere.

The famine of 1932-1933 was a thoroughly planned civil war.

War politicizes every context and strategically redeploys every means.

Stalin politicized the very identity of the Ukrainian people and meticulously planned the destruction of a nation by selectively distributing confiscated food.

The Marxist economic view he espoused distorted the existence of peasants.

Peasants deserved to be sacrificed for the industrialization of the Soviet Union, and therefore their land and grain should be donated to the state.

In particular, the wealthy peasants, the 'kulaks', who owned private property, were no different from class enemies and had to be purged first.

Only farm collectivization and communal farm reform could lead to true proletarian transformation.

Stalin's obsessive belief, though dressed up in the language of 'revolution', amounted to colonizing his own people, and the disastrous results were proof of this.

“Russians moved into the empty houses where the owners starved to death or fled, weakening Ukraine’s national identity.

Stalin, who persistently pushed forward this brutal policy and purged revolutionary comrades who opposed it by labeling them reactionaries, seized absolute power and held a 'victors' congress'.

“It was January 1934, after four million Ukrainians had died.”

Ukraine is not alone in suffering from famine.

Especially in Russia's Volga region, countless people starved due to Stalin's indiscriminate grain confiscation orders, no less than in Ukraine.

Evidence of famine damage throughout the Soviet Union has reduced Ukraine to a laughing stock, exaggerating its own losses.

However, Applebaum, quoting historian Andrea Graziosi, points out that “no one confuses the general history of ‘Nazi atrocities’ with the very specific story of Hitler’s genocide of Jews and Gypsies.”

If the famine that swept across the Soviet Union was a major strand of history, Ukraine's special situation is a branch branching off from it.

And to get closer to the truth through history, we must pave the way for more stems to spread out like leaf veins.

This is also the perspective that Anne Applebaum presents in this book, and it is also here that we can understand why she gave the book the subtitle, 'Stalin's War in Ukraine.'

Soviet historian Sheila Fitzpatrick discusses the question of "intention," arguing that Stalin's intention was not to kill millions, but to obtain as much grain as possible.

However, he acknowledges Applebaum's argument as a legitimate difference of interpretation, and furthermore, he believes that Applebaum's book not only exposes the political and academic impulse to downplay the Soviet famine, but also provides historians with interesting insights by examining how Ukraine exploited the issue after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Applebaum synthesizes correspondence between Stalin and his entourage, secret police reports, and various documents handed down to local party officials to uncover Stalin's ambition to exterminate the Ukrainian people, a thorn in Russia's side.

Russia never recognized Ukraine as a sovereign state in the first place.

Since the time of the Russian Empire, Ukraine has been considered a remote village of Russia.

Ukrainian was nothing more than a dialect of Russian, and Ukrainians were an ignorant and uncivilized people, little more than former serfs.

But no matter how the surrounding powers defined Ukraine, a unique national identity emerged in this land.

That is why, when the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917, Ukraine finally felt that its opportunity had come to establish its own sovereign state.

The demonstrations that took place in Kiev on April 1st of that year became a nightmare for the Soviet Union and continued to make Stalin anxious.

Ukrainian people and peasants were almost synonymous.

This is because the nationalist movement began with the restoration of the Ukrainian language and culture, which were usually found only in rural areas.

Thus, Stalin's deep-rooted distrust and contempt for the peasantry was part of a paranoia that, along with the problem of revolutionary ideology, he would crush any remnant of national identity that might pose a threat to Russia.

Applebaum analyzes the material he has gathered to trace the path this madness took, leading to frenzied grain plunder, confiscations, extraordinary measures, mass purges, the Gulag, and the Holodomor.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

preface

Introduction: The Ukrainian Problem

Chapter 1: The Ukrainian Revolution, 1917

Chapter 2: The Rebellion, 1919

Chapter 3: Famine and Armistice, 1920s

Chapter 4: The Double Crisis, 1927–1929

Chapter 5: Collectivization: Revolution in the Rural Areas, 1930

Chapter 6: Rebellion, 1930

Chapter 7: The Failure of Collectivization, 1931–1932

Chapter 8: The Decision to Promote Famine, 1932: Requisitions, Blacklists, and Border Closures

Chapter 9: The Decision to Promote Famine, 1932: The End of Ukrainianization

Chapter 10: The Decision to Promote Famine, 1932: The Search and the Searchers

Chapter 11: Hunger: Spring and Summer, 1933

Chapter 12 Survival: Spring and Summer, 1933

Chapter 13: The Famine and Aftermath

Chapter 14 Concealment

Chapter 15: The Holodomor in History and Memory

Conclusion: Reflecting on the Ukraine Issue

Translator's Note

main

References

Photo source

Search

Introduction: The Ukrainian Problem

Chapter 1: The Ukrainian Revolution, 1917

Chapter 2: The Rebellion, 1919

Chapter 3: Famine and Armistice, 1920s

Chapter 4: The Double Crisis, 1927–1929

Chapter 5: Collectivization: Revolution in the Rural Areas, 1930

Chapter 6: Rebellion, 1930

Chapter 7: The Failure of Collectivization, 1931–1932

Chapter 8: The Decision to Promote Famine, 1932: Requisitions, Blacklists, and Border Closures

Chapter 9: The Decision to Promote Famine, 1932: The End of Ukrainianization

Chapter 10: The Decision to Promote Famine, 1932: The Search and the Searchers

Chapter 11: Hunger: Spring and Summer, 1933

Chapter 12 Survival: Spring and Summer, 1933

Chapter 13: The Famine and Aftermath

Chapter 14 Concealment

Chapter 15: The Holodomor in History and Memory

Conclusion: Reflecting on the Ukraine Issue

Translator's Note

main

References

Photo source

Search

Detailed image

Into the book

The book begins in 1917.

At that time, the Ukrainian Revolution took place, and the Ukrainian national movement was launched, but it was destroyed by the famine of 1932-1933.

The end of the book is the present.

It concludes by discussing the ongoing politics of memory in Ukraine.

Historian Andrea Graziosi points out that no one confuses the general history of "Nazi atrocities" with the very specific story of Hitler's genocide of Jews and Gypsies.

Following the same logic, the book discusses the high mortality rates caused by the massive famine that the Soviet Union suffered between 1930 and 1934, particularly in Kazakhstan and other Soviet peripheries, but focuses more directly on the tragedy suffered by Ukraine.

--- p.20~21

Now, and only now, when famine is raging in the lands where people are being devoured, and when hundreds if not thousands of corpses lie in the streets, we can (and must) use the most mad and ruthless energy to destroy Church property with the least resistance.

Now, and only now, the majority of the peasants will be on our side, or at least will not stand in the position of helping this handful of (reactionary) priests and the reactionary urban petty bourgeoisie.

--- p.153

Exhibition communism failed.

The radical workers' state failed to bring prosperity to workers.

But by the late 1920s, Lenin's New Economic Policy was also failing.

--- p.186

If you work hard and grow your farm, you become a kulak, an 'enemy of the people'.

But if you choose to remain a poor farmer, a Bednyak, you will be worse off than your rival, the 'American farmer'.

There seemed to be no way out of this trap.

“What should we do now?” Ivanisov asked his friend.

“How should I eat and live?” The situation was getting worse.

“We have to sell the cow now.

Without cows, there would be nothing left.

The peasant's house is filled with tears, endless screams, pain and curses.

If you come here and visit a peasant's home, you will hear the same thing.

'This is not living.

It's hard work, it's hell, it's such a horrible thing that even the devil doesn't know.

“There is nothing left but pain.”

--- p.193~194

Like everyone in my generation, I firmly believed that the ends justify the means.

The great goal we pursued was the universal victory of communism, and if it could achieve this goal, lying, stealing, and even killing hundreds of thousands or millions of people who could interfere with or hinder our work were permissible.

And to hesitate or doubt about all this was to succumb to the 'intellectual cowardice' and 'foolish liberalism' that characterize people who 'cannot see the forest for the trees'.

--- p.243~244

The mere fact that he was alive raised suspicion.

Being alive meant having food.

But if you had food, you had to hand it over, otherwise you were considered a kulaks, Petliurapa, Polish spy or other enemy.

A group searching the house of Mikhailo Balanovsky in Cherkasy Oblast demanded an explanation: “How is it that no one in this family has died?”51 A group searching the roof thatch of Khrykhori Moroz in Sumy Oblast, finding no food, asked: “Who is helping you survive?”52 As the days passed, the demands grew louder and the language became more ruder.

Why haven't you disappeared yet? Why haven't you died yet? Why on earth are you still alive?

--- p.446

The fear and exhaustion, the inhumane indifference to life, and the constant exposure to the language of hate left their mark.

These factors, combined with extreme food shortages, have led to a form of madness that is very rare in rural Ukraine.

In late spring and summer, cannibalism became widespread.

--- p.500

In the 1970s and 1980s, the concept of a large-scale Ukrainian national movement seemed completely dead and buried.

Although intellectuals kept the flame alive in some cities, most Russians and many Ukrainians considered Ukraine a province of Russia.

Outsiders could not distinguish between Russia and Ukraine, and some even forgot the name Ukraine itself.

--- p.569

Diaspora scholar Frank Cissin has written that the “ethnicization” of academia may have made Ukrainian history seem like a secondary and unworthy subject of study, alienating it from other academic disciplines.44 Furthermore, because of the memory of the Nazi occupation and the fact that some Ukrainians collaborated with the Nazis, advocates for an independent Ukraine were often labeled “fascists” decades later.

Those who left Ukraine and clung to their own identities were seen by many North Americans and Europeans as mere "nationalists," and as a result, they were viewed with suspicion.

--- p.645~646

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian state again put forward 'complete denial' about the famine.

The Holodomor never happened, only the Nazis claim so.

All these controversies have made it difficult to apply the word 'genocide'.

In Russia and Ukraine, the word has become so controversial that its mere use is considered tiresome.

People were tired of the debate, and perhaps this was precisely why Russia attacked the historiography that dealt with the famine.

--- p.684

Today, the Russian government, much like the Soviet government in the past, is using disinformation, corruption, and military force to undermine Ukrainian sovereignty.

Russia's continued references to "war" and "enemy", as in 1932, remain a useful tool for Russian leaders who cannot explain stagnant living standards or justify the privileges, wealth, and power they enjoy.

--- p.690

As the lyrics of the Ukrainian national anthem declare, Ukraine is not dead.

In the end, Stalin failed.

An entire generation of Ukrainian intellectuals and politicians were murdered in the 1930s, but their legacy lived on.

In the 1960s, nationalist aspirations were revived, in the 1970s and 1980s they persisted underground, and in the 1990s they emerged publicly again.

In the 2000s, a new generation of Ukrainian intellectuals and activists emerged.

The history of famine is a tragedy without a happy ending.

But Ukraine's history is not a tragedy.

At that time, the Ukrainian Revolution took place, and the Ukrainian national movement was launched, but it was destroyed by the famine of 1932-1933.

The end of the book is the present.

It concludes by discussing the ongoing politics of memory in Ukraine.

Historian Andrea Graziosi points out that no one confuses the general history of "Nazi atrocities" with the very specific story of Hitler's genocide of Jews and Gypsies.

Following the same logic, the book discusses the high mortality rates caused by the massive famine that the Soviet Union suffered between 1930 and 1934, particularly in Kazakhstan and other Soviet peripheries, but focuses more directly on the tragedy suffered by Ukraine.

--- p.20~21

Now, and only now, when famine is raging in the lands where people are being devoured, and when hundreds if not thousands of corpses lie in the streets, we can (and must) use the most mad and ruthless energy to destroy Church property with the least resistance.

Now, and only now, the majority of the peasants will be on our side, or at least will not stand in the position of helping this handful of (reactionary) priests and the reactionary urban petty bourgeoisie.

--- p.153

Exhibition communism failed.

The radical workers' state failed to bring prosperity to workers.

But by the late 1920s, Lenin's New Economic Policy was also failing.

--- p.186

If you work hard and grow your farm, you become a kulak, an 'enemy of the people'.

But if you choose to remain a poor farmer, a Bednyak, you will be worse off than your rival, the 'American farmer'.

There seemed to be no way out of this trap.

“What should we do now?” Ivanisov asked his friend.

“How should I eat and live?” The situation was getting worse.

“We have to sell the cow now.

Without cows, there would be nothing left.

The peasant's house is filled with tears, endless screams, pain and curses.

If you come here and visit a peasant's home, you will hear the same thing.

'This is not living.

It's hard work, it's hell, it's such a horrible thing that even the devil doesn't know.

“There is nothing left but pain.”

--- p.193~194

Like everyone in my generation, I firmly believed that the ends justify the means.

The great goal we pursued was the universal victory of communism, and if it could achieve this goal, lying, stealing, and even killing hundreds of thousands or millions of people who could interfere with or hinder our work were permissible.

And to hesitate or doubt about all this was to succumb to the 'intellectual cowardice' and 'foolish liberalism' that characterize people who 'cannot see the forest for the trees'.

--- p.243~244

The mere fact that he was alive raised suspicion.

Being alive meant having food.

But if you had food, you had to hand it over, otherwise you were considered a kulaks, Petliurapa, Polish spy or other enemy.

A group searching the house of Mikhailo Balanovsky in Cherkasy Oblast demanded an explanation: “How is it that no one in this family has died?”51 A group searching the roof thatch of Khrykhori Moroz in Sumy Oblast, finding no food, asked: “Who is helping you survive?”52 As the days passed, the demands grew louder and the language became more ruder.

Why haven't you disappeared yet? Why haven't you died yet? Why on earth are you still alive?

--- p.446

The fear and exhaustion, the inhumane indifference to life, and the constant exposure to the language of hate left their mark.

These factors, combined with extreme food shortages, have led to a form of madness that is very rare in rural Ukraine.

In late spring and summer, cannibalism became widespread.

--- p.500

In the 1970s and 1980s, the concept of a large-scale Ukrainian national movement seemed completely dead and buried.

Although intellectuals kept the flame alive in some cities, most Russians and many Ukrainians considered Ukraine a province of Russia.

Outsiders could not distinguish between Russia and Ukraine, and some even forgot the name Ukraine itself.

--- p.569

Diaspora scholar Frank Cissin has written that the “ethnicization” of academia may have made Ukrainian history seem like a secondary and unworthy subject of study, alienating it from other academic disciplines.44 Furthermore, because of the memory of the Nazi occupation and the fact that some Ukrainians collaborated with the Nazis, advocates for an independent Ukraine were often labeled “fascists” decades later.

Those who left Ukraine and clung to their own identities were seen by many North Americans and Europeans as mere "nationalists," and as a result, they were viewed with suspicion.

--- p.645~646

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian state again put forward 'complete denial' about the famine.

The Holodomor never happened, only the Nazis claim so.

All these controversies have made it difficult to apply the word 'genocide'.

In Russia and Ukraine, the word has become so controversial that its mere use is considered tiresome.

People were tired of the debate, and perhaps this was precisely why Russia attacked the historiography that dealt with the famine.

--- p.684

Today, the Russian government, much like the Soviet government in the past, is using disinformation, corruption, and military force to undermine Ukrainian sovereignty.

Russia's continued references to "war" and "enemy", as in 1932, remain a useful tool for Russian leaders who cannot explain stagnant living standards or justify the privileges, wealth, and power they enjoy.

--- p.690

As the lyrics of the Ukrainian national anthem declare, Ukraine is not dead.

In the end, Stalin failed.

An entire generation of Ukrainian intellectuals and politicians were murdered in the 1930s, but their legacy lived on.

In the 1960s, nationalist aspirations were revived, in the 1970s and 1980s they persisted underground, and in the 1990s they emerged publicly again.

In the 2000s, a new generation of Ukrainian intellectuals and activists emerged.

The history of famine is a tragedy without a happy ending.

But Ukraine's history is not a tragedy.

--- p.691

Publisher's Review

A curse to survive the impossible

With honest, uncompromising commitment, what will we build as truth?

“We appeal to everyone, especially to the Russian Federation.

Be truthful, honest, and sincere before your brothers in denouncing the crimes of Stalinism and the totalitarian USSR… … We were all in the same hell.

We reject the blatant lie that we blame a particular individual for our tragedy.

This is not true.

“There is only one culprit: the imperialist communist Soviet regime.”

Even when the Nazis invaded Ukraine, the framework of repression laid down by Stalin was restored, with only wartime slogans changed.

Even after the war ended, the language of the regime had changed.

Since Hitler used Soviet grain-grabbing policies in his propaganda, exposing Soviet atrocities by mentioning the Ukrainian famine was considered collaboration with the Nazis.

Indeed, the fact that some Ukrainians collaborated with the Nazis made the fight for an independent Ukraine more difficult.

The West turned to Ukraine.

"If such a famine existed, why didn't the Ukrainian government respond? What government would stand by and watch its own people starve?"

But by the 1980s, changes had begun to take place in the Ukrainian diaspora.

Diaspora groups, having escaped poverty and refugee status, are gathering scattered literary sources and oral testimonies, organizing research, and getting closer to the reality of the Ukrainian famine.

Moreover, the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident in 1986 not only undermined the belief that Soviet communism could lead its people into a future of high-tech development, but also raised doubts about the catastrophic consequences of Soviet secrecy.

The hidden truth was slowly coming to light.

And it was only after Ukraine's independence in 1991 that the full extent of the famine was revealed.

Rafał Lemkin, who coined the term “genocide,” called the Ukrainian famine a “classic example” of the concept.

Genocide is a 'process' of annihilating an entire nation, not an individual.

As hunger becomes more severe, the material foundation of the body and the spiritual foundation of the soul gradually disappear, and a nation is gradually erased from history.

History tells us that this is too easy.

Hardened ideologies and paranoia fuel each other, and deep-rooted exclusion and contempt are inertial.

We remember February 24, 2022, the day Russia bombed Ukraine.

Even today, the Russian government uses disinformation, corruption, and military force to undermine Ukrainian sovereignty.

The curse that was inflicted on the land of Ukraine 100 years ago, a curse to live as if dead, to survive the impossible, is being repeated.

But we remember at the same time.

The Ukrainian people returned, as if in a Soviet nightmare, unfazed, and the survivors dug up and opened the diaries they had buried in the ground to avoid surveillance. Stalin failed, and the Ukrainian legacy lived on.

We, who stand before this history, must choose what to build as truth through uncompromising honesty.

And then the contemporary slaughter scene embodied by Applebaum and countless testimonies will become an irreplaceable narrative.

With honest, uncompromising commitment, what will we build as truth?

“We appeal to everyone, especially to the Russian Federation.

Be truthful, honest, and sincere before your brothers in denouncing the crimes of Stalinism and the totalitarian USSR… … We were all in the same hell.

We reject the blatant lie that we blame a particular individual for our tragedy.

This is not true.

“There is only one culprit: the imperialist communist Soviet regime.”

Even when the Nazis invaded Ukraine, the framework of repression laid down by Stalin was restored, with only wartime slogans changed.

Even after the war ended, the language of the regime had changed.

Since Hitler used Soviet grain-grabbing policies in his propaganda, exposing Soviet atrocities by mentioning the Ukrainian famine was considered collaboration with the Nazis.

Indeed, the fact that some Ukrainians collaborated with the Nazis made the fight for an independent Ukraine more difficult.

The West turned to Ukraine.

"If such a famine existed, why didn't the Ukrainian government respond? What government would stand by and watch its own people starve?"

But by the 1980s, changes had begun to take place in the Ukrainian diaspora.

Diaspora groups, having escaped poverty and refugee status, are gathering scattered literary sources and oral testimonies, organizing research, and getting closer to the reality of the Ukrainian famine.

Moreover, the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident in 1986 not only undermined the belief that Soviet communism could lead its people into a future of high-tech development, but also raised doubts about the catastrophic consequences of Soviet secrecy.

The hidden truth was slowly coming to light.

And it was only after Ukraine's independence in 1991 that the full extent of the famine was revealed.

Rafał Lemkin, who coined the term “genocide,” called the Ukrainian famine a “classic example” of the concept.

Genocide is a 'process' of annihilating an entire nation, not an individual.

As hunger becomes more severe, the material foundation of the body and the spiritual foundation of the soul gradually disappear, and a nation is gradually erased from history.

History tells us that this is too easy.

Hardened ideologies and paranoia fuel each other, and deep-rooted exclusion and contempt are inertial.

We remember February 24, 2022, the day Russia bombed Ukraine.

Even today, the Russian government uses disinformation, corruption, and military force to undermine Ukrainian sovereignty.

The curse that was inflicted on the land of Ukraine 100 years ago, a curse to live as if dead, to survive the impossible, is being repeated.

But we remember at the same time.

The Ukrainian people returned, as if in a Soviet nightmare, unfazed, and the survivors dug up and opened the diaries they had buried in the ground to avoid surveillance. Stalin failed, and the Ukrainian legacy lived on.

We, who stand before this history, must choose what to build as truth through uncompromising honesty.

And then the contemporary slaughter scene embodied by Applebaum and countless testimonies will become an irreplaceable narrative.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: September 8, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 816 pages | 1,078g | 149*217*52mm

- ISBN13: 9791169094207

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)