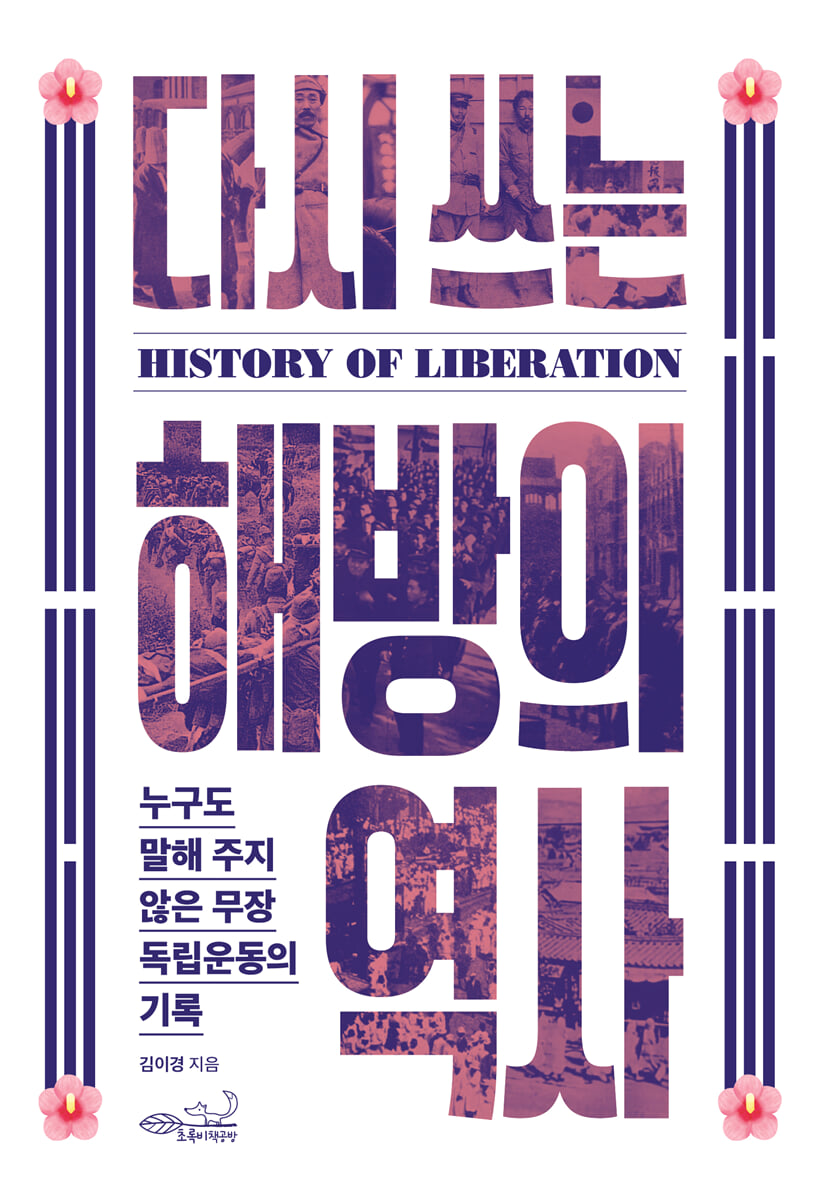

Rewriting the History of Liberation

|

Description

Book Introduction

80th Anniversary of Liberation: Now is the Time to Tell the Truth

Rewriting the Hidden Truth of Liberation

2025 marks the 80th anniversary of liberation.

Countless patriotic martyrs sacrificed their lives for the liberation of our country.

During the independence movement, there was no division between the South and the North.

The liberation of the fatherland was the earnest wish and goal of all Koreans, transcending ideology.

However, after the division, the perspectives on the history of liberation changed significantly amidst different ideologies and perspectives.

"Rewriting the History of Liberation" is a book that reconstructs the history of Korea from the end of the Japanese colonial period to immediately after liberation through historical materials, testimonies, and research from both the South and the North.

The author, who has been involved in civilian exchanges between the South and the North since 2001, has felt that the South and the North, who share a common history, have quite different perspectives on the history of liberation.

Based on that experience, we aim to restore the North's independence movement, which is largely unknown in the South, and thereby open a new chapter in understanding the North and historical exchange between the two Koreas.

Rewriting the Hidden Truth of Liberation

2025 marks the 80th anniversary of liberation.

Countless patriotic martyrs sacrificed their lives for the liberation of our country.

During the independence movement, there was no division between the South and the North.

The liberation of the fatherland was the earnest wish and goal of all Koreans, transcending ideology.

However, after the division, the perspectives on the history of liberation changed significantly amidst different ideologies and perspectives.

"Rewriting the History of Liberation" is a book that reconstructs the history of Korea from the end of the Japanese colonial period to immediately after liberation through historical materials, testimonies, and research from both the South and the North.

The author, who has been involved in civilian exchanges between the South and the North since 2001, has felt that the South and the North, who share a common history, have quite different perspectives on the history of liberation.

Based on that experience, we aim to restore the North's independence movement, which is largely unknown in the South, and thereby open a new chapter in understanding the North and historical exchange between the two Koreas.

- You can preview some of the book's contents.

Preview

index

In order to establish a complete, not half-baked, history of the independence movement,

Part 1.

Begin national resistance

I'd rather die standing than live on my knees.

The March 1st Movement that opened the gates to independence

The Two Faces of the Independence Movement in the 1920s

From West Gando to Cheongsanri, the Armed Independence Movement Unfolds

Division and Unification, from the Gyeongsin Massacre to the Unification of the Three Kingdoms

Part 2.

Raising a new banner for the independence movement

The young revolution that began in Jilin

A New Milestone in the Independence Movement: The Kalun Conference

Raising the first flag of revolution

Part 3.

Opening the prelude to the anti-Japanese war

Beginning a guerrilla war with the people

A liberated area built by the power of the people

The days of the Sowangcheong guerrilla base

The leap forward in armed struggle and the securing of the legitimacy of Korean communism

Towards a wider front

Part 4.

The Korean People's Revolutionary Army, the main force in the war for independence

A watershed moment for the Korean Revolution

The Korean People's Revolutionary Army Opens a New Era

The Fatherland Restoration Association established with revolutionary comrades

Expansion into Musong and the Jangbaek region

From "Sea of Blood" to Secret Camp, the Flame of Anti-Japanese Resistance Embraced by Baekdu Mountain

Japanese offensive and guerrilla response

Underground revolutionary organizations are being built one after another

Battle of Pochonbo

Part 5.

Time for reorganization and counterattack

The Sino-Japanese War and Korea's Anti-Japanese Strategy

Back to the homeland while rebuilding the organization

Reorganization and counterattack of guerrilla warfare

Arduous March

Part 6.

Domestic political and military activities intensify

Spring's March to the Fatherland

The spark of national liberation sprouting from underground

From Gyegwan Raja to Hong Giha, the path of counterattack

Part 7.

Achieve liberation through one's own efforts

Transition to small unit activities

Strategy for national liberation through small unit activities

Preparation for the liberation of the fatherland

Final preparations for an all-out attack

The last general offensive that took place across the country

Liberation achieved by the people beyond surrender

Part 1.

Begin national resistance

I'd rather die standing than live on my knees.

The March 1st Movement that opened the gates to independence

The Two Faces of the Independence Movement in the 1920s

From West Gando to Cheongsanri, the Armed Independence Movement Unfolds

Division and Unification, from the Gyeongsin Massacre to the Unification of the Three Kingdoms

Part 2.

Raising a new banner for the independence movement

The young revolution that began in Jilin

A New Milestone in the Independence Movement: The Kalun Conference

Raising the first flag of revolution

Part 3.

Opening the prelude to the anti-Japanese war

Beginning a guerrilla war with the people

A liberated area built by the power of the people

The days of the Sowangcheong guerrilla base

The leap forward in armed struggle and the securing of the legitimacy of Korean communism

Towards a wider front

Part 4.

The Korean People's Revolutionary Army, the main force in the war for independence

A watershed moment for the Korean Revolution

The Korean People's Revolutionary Army Opens a New Era

The Fatherland Restoration Association established with revolutionary comrades

Expansion into Musong and the Jangbaek region

From "Sea of Blood" to Secret Camp, the Flame of Anti-Japanese Resistance Embraced by Baekdu Mountain

Japanese offensive and guerrilla response

Underground revolutionary organizations are being built one after another

Battle of Pochonbo

Part 5.

Time for reorganization and counterattack

The Sino-Japanese War and Korea's Anti-Japanese Strategy

Back to the homeland while rebuilding the organization

Reorganization and counterattack of guerrilla warfare

Arduous March

Part 6.

Domestic political and military activities intensify

Spring's March to the Fatherland

The spark of national liberation sprouting from underground

From Gyegwan Raja to Hong Giha, the path of counterattack

Part 7.

Achieve liberation through one's own efforts

Transition to small unit activities

Strategy for national liberation through small unit activities

Preparation for the liberation of the fatherland

Final preparations for an all-out attack

The last general offensive that took place across the country

Liberation achieved by the people beyond surrender

Detailed image

Into the book

For a country under the colonial rule of a powerful country to achieve independence, national spirit and self-confidence are essential above all else.

Japan's policy of internal integration was an attempt to destroy this spirit, but the March 1st Movement clearly demonstrated that our entire people possessed the will to fight against Japanese imperialism.

Although this movement did not immediately bring about independence, it became a turning point that broadened the direction and horizon of the subsequent independence movement.

(…) The March 1st Movement also had an influence overseas.

Indian independence activist Jawaharlal Nehru heard news of the March 1st Movement from prison and sent a letter to his daughter.

“In the March 1st Movement in Korea in 1919, the Korean people, especially young men and women, fought bravely against an overwhelming enemy.

In Joseon, even young women who had just graduated from school are said to have played an important role in the independence movement.

I believe you too will be deeply moved by this story.”

--- p.26

The two-year military school Hwasong Uisuk run by the Justice Department in Jilin Hwajeon was mainly attended by children of independence activists and students from the independence army, from 15-year-old Kim Seong-ju to 20-year-old Choi Chang-geol.

At the center of it all was Kim Seong-ju, the eldest son of Kim Hyung-jik, the leader of the Joseon National Association.

He entered Hwaseong High School in 1926 on the recommendation of his father's friends.

The students wanted to become independence fighters and contribute to the independence of their country, but they were disappointed with the outdated nationalist education at Hwaseong High School.

Even the armed struggle manual was not properly equipped, and the history education centered on the Joseon Dynasty was not interesting.

Above all, Hwaseong High School was ideologically closed to the point that anyone who read communist literature could be expelled.

They judged that independence would be difficult to achieve through the provisional government's diplomatic focus or limited armed struggle alone.

He began to take an interest in the Soviet Revolution in Russia by secretly reading communist books.

--- p.57~58

The activities of the members of the Overthrow Imperialism League were known beyond Jilin and even reached Seoul and Shanghai, and people said, “A new wind is blowing in Jilin.”

“If you want to fight for independence, you have to go to Jilin,” he said.

This wind was called the 'Jilin Wind' and spread widely.

Among the young men who came to see Kim Seong-ju after hearing this rumor, Cha Gwang-su and Kim Hyeok later became his closest comrades.

Around this time, Kim Seong-ju was also called 'Kim Il-sung' or 'Hanbyeol'.

In October 1928, Kim Seong-ju organized a demonstration against the construction of the Gilhoe Line railroad and issued a statement condemning it.

The protests soon spread throughout Manchuria, and Kim Seong-ju expanded them into a movement to boycott Japanese goods.

As a result, the Chinese people resisted by taking Japanese products out of Japanese stores and throwing them into the Songhua River or burning them.

The protests against the construction of the Gilhoe Line railroad and the boycott of Japanese goods, which lasted for about 40 days from October to November 1928, were the first mass anti-Japanese struggles led by Kim Seong-ju.

--- p.62~63

On December 16, 1931, about 40 young fighters, including Kim Il-sung, Cha Gwang-su, and Lee Gwang, gathered in Myeongwol District, Yanji County and began preparations to establish the Anti-Japanese People's Guerrilla Force.

The Anti-Japanese People's Guerrilla Army was a revolutionary army composed of children of workers and peasants, fighting for the liberation of the fatherland and the freedom and happiness of the people.

They planned to seize Japanese weapons, arm themselves, and establish a liberated area through guerrilla warfare, then install a revolutionary government, schools, hospitals, weapons repair shops, and publishing houses within it.

It was decided to form a semi-guerrilla zone by placing revolutionary rural areas around the guerrilla zone.

In each county of Dongman, small guerrilla groups of 1 to 20 people were organized, and in early March 1932, in Sosaha, Ando, a youth guerrilla group of 18 people directly commanded by Kim Il-sung was formed.

Afterwards, guerrilla organizations continued to form in various places.

For the young Koreans who had to just beat their chests and cry while losing their families to the Japanese army right before their eyes, taking up real guns and fighting the Japanese was a fervent wish and hope.

--- p.77~78

Even as Chinese and Korean independence activists fled to China immediately after the Manchurian Incident in 1931, Kim Il-sung raised the slogan, “Armed with Arms,” and set out to establish the Anti-Japanese People’s Guerrilla Army.

In 1934, when the Japanese surrounded and pressured the guerrilla base, he responded with a surprise attack from behind rather than a passive defense.

He responded to the unprecedented and vicious suppression known as Operation Weigong by further expanding the guerrilla zone, and eventually voluntarily disbanded the guerrilla zone, thereby breaking away from defensive battles and launching an expedition to northern Manchuria.

As a result, the flag of the Korean People's Revolutionary Army was able to fly even more vigorously.

The confidence in this offensive strategy stems from the people's independent line, which is the starting point of Kim Il-sung's ideology.

In the mid-1930s, while many patriotic leaders who supported the independence movement remained silent or defected, Kim Il-sung found hope among the people.

As the oppression of the Japanese became more severe, the people, who had lost everything, had no choice but to engage in an even more fierce anti-Japanese struggle.

His policy was to believe in the people and achieve independence through their power.

--- p.115~116

But he was moved by the sight of the people rising up with guns and clubs in the midst of such tragedy.

In particular, the scene where women took part in the anti-Japanese struggle left a strong impression.

Kim Il-sung wanted to create a play featuring such women as the main characters.

(…) The curtain finally rose on the play.

The atrocities of the Japanese that turned the entire village into a sea of blood, the lamentations of a family that lost their husbands and fathers, and the images of mothers and children who were reborn as fighters unfolded on stage.

The audience wept, and one old man jumped onto the stage and struck the forehead of the actor playing the leader of the punitive expedition with a long stick.

As the performance ended, applause poured in.

“Let us also join the fight against the Japanese!” The young men petitioned to enlist, and the villagers enjoyed the play by lamplight until past midnight.

The performance of “Sea of Blood” transformed the blind mountain villagers into supporters and direct participants in the anti-Japanese struggle.

When a revolutionary battlefield survey team visited Manjiang some 20 years later, the residents vividly remembered the names of the characters, the plot, and even the dialogue.

The shock and impression that the performance of “Sea of Blood” left on the villagers at the time was deep.

--- p.141~142

The Battle of Pochonbo was an ordinary raid without aircraft or tanks, but the way it unfolded demonstrated the essence of guerrilla warfare.

It was a three-dimensional battle in which all elements were meticulously combined, including target setting, timing selection, surprise attacks, psychological shock through arson, and even political propaganda.

(…) 1937 was a time when colonial rule was further strengthened and the domestic national movement was suppressed and stagnant before and after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War.

The Battle of Pochonbo, which broke out at this time, rekindled the spark of national liberation.

“The Korean people are alive and not dead.

“If we fight against the Japanese, we can win.” The flames of Pochonbo spread this conviction throughout the country.

The guerrillas, having finished the battle, escaped with clubs.

The members each put a handful of soil from their homeland into their backpacks.

A handful of soil from the motherland was like a heart to the guerrillas.

--- p.174~175

The column advancing to the fatherland left Begibong Peak and continued to march until it finally reached Samjiyeon Pond.

In that place where clear, blue waves rippled, the team members rushed to drink water and quench their thirst.

Azaleas were in full bloom along the pond, and their reflections were clearly visible on the still water.

The scenery above and below the water, reality and reflection mixed together, was truly breathtaking.

The members were so immersed in the peace and joy they felt in the embrace of their homeland that they felt like building a hut and staying there.

The unique alpine atmosphere of Baekdu Plain and the peaceful harmony of the fields were a beauty of the motherland that could not be exchanged for a billion dollars.

But that beauty soon gave way to the sorrow of colonial reality.

Facing the majestic mountains and rivers, the members felt anew how precious our people's land had been taken away by the Japanese.

--- p.208~209

The Korean People's Revolutionary Army Command held meetings of the organization leaders of the Fatherland Restoration Association at a secret temporary base on Sangdansan Mountain in Yeonsa-myeon, Musan County in July 1944 and June 1945.

At this meeting, it was decided to expand the Fatherland Restoration Movement nationwide to further expand national unity.

At that time, various independence movement forces at home and abroad were also paying attention to the activities of the Korean People's Revolutionary Army.

Kim Gu of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in Chongqing attempted to establish contact by sending a liaison officer and also appealed to Koreans living in the United States to raise funds to support the Korean People's Revolutionary Army.

Yeo Un-hyeong also sought cooperation from 1944, and the Korean Independence Alliance and the Korean Volunteer Army also showed signs of cooperation.

In this way, the Korean People's Revolutionary Army emerged as more than just a simple armed force, becoming a central axis where the hopes of the Korean people gathered and where independence movement forces at home and abroad cooperated.

--- p.246~247

On August 9, 1945, when the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and entered the war, Kim Il-sung also gave the order for a general attack to liberate the fatherland.

The Korean People's Revolutionary Army, together with the Soviet Army, entered the great battle for national liberation by eliminating the Japanese army.

The Soviet Army was impressed by the Korean People's Revolutionary Army's sacrifice of their lives for the liberation of the nation and the people.

The greatest task of the fatherland liberation operation was to break through the border fortresses along the Tumen River.

Japan boasted of the Gyeongheung, Najin, and Unggi fortresses, as well as the Hunchun and Dongheungjin fortresses in Manchuria, as "impregnable defense lines."

If the Allied Forces failed to break through this defensive line, the victory of the general offensive operation could not be guaranteed.

(…) The fortress of Unggi at the mouth of the Tuman River was a key military stronghold located between Gyeongheung and Najin, and if it fell, both fortresses would be threatened.

Oh Baek-ryong's small unit crossed the Tumen River by surprise in heavy rain, attacked a Japanese military post, and liberated the Tori area.

They watched the police station burning before reinforcements could even approach and withdrew.

At the same time, a surprise attack was successful at Nambyeol-ri and Dongheungjin in Hunchun, Manchuria, causing confusion in the Japanese defense network and exposing weaknesses in the defense line.

With the border fortresses, which were considered impregnable, being taken over in one fell swoop, a breakthrough for the liberation of the fatherland was opened.

This means that the Korean People's Revolutionary Army took the lead in breaking through the decisive battles of the war against Japan and took the lead in liberation.

--- p.255~256

Even after Japan's surrender on August 15, 1945, the Korean People's Revolutionary Army continued military operations.

(…) Along with this, the Fatherland Restoration Association, the National Resistance Organization, and the people rose up in armed uprisings in various places to help the military advance.

At the heart of the people's armed organizations, which have various names such as the Red Guard, Security Corps, Autonomous Corps, and Self-Defense Corps, there have always been members of revolutionary organizations.

(…) According to statistics, excluding South and North Hamgyong Provinces, which had already been liberated by the Korean People's Revolutionary Army and the Soviet Army, armed uprisings and demonstrations occurred in over 1,000 places across the country from August 13 to 23, effectively paralyzing the Japanese ruling system.

The people organized people's committees in each liberated area and created a new order.

For example, in South Hamgyong Province, people's committees were formed in three cities, 16 counties, and 129 townships by the end of August.

In this way, our people began to practice building an independent and autonomous nation.

The liberation of our people was achieved through the power of the Korean People's Revolutionary Army and the people themselves, under favorable conditions in which the Sino-Soviet Allied Forces defeated the Japanese Kwantung Army.

The final offensive operation, the people's active resistance, and the rear strike operation carried out under Kim Il-sung's orders were the driving force behind the collapse of the Japanese colonial rule and the achievement of liberation.

Japan's policy of internal integration was an attempt to destroy this spirit, but the March 1st Movement clearly demonstrated that our entire people possessed the will to fight against Japanese imperialism.

Although this movement did not immediately bring about independence, it became a turning point that broadened the direction and horizon of the subsequent independence movement.

(…) The March 1st Movement also had an influence overseas.

Indian independence activist Jawaharlal Nehru heard news of the March 1st Movement from prison and sent a letter to his daughter.

“In the March 1st Movement in Korea in 1919, the Korean people, especially young men and women, fought bravely against an overwhelming enemy.

In Joseon, even young women who had just graduated from school are said to have played an important role in the independence movement.

I believe you too will be deeply moved by this story.”

--- p.26

The two-year military school Hwasong Uisuk run by the Justice Department in Jilin Hwajeon was mainly attended by children of independence activists and students from the independence army, from 15-year-old Kim Seong-ju to 20-year-old Choi Chang-geol.

At the center of it all was Kim Seong-ju, the eldest son of Kim Hyung-jik, the leader of the Joseon National Association.

He entered Hwaseong High School in 1926 on the recommendation of his father's friends.

The students wanted to become independence fighters and contribute to the independence of their country, but they were disappointed with the outdated nationalist education at Hwaseong High School.

Even the armed struggle manual was not properly equipped, and the history education centered on the Joseon Dynasty was not interesting.

Above all, Hwaseong High School was ideologically closed to the point that anyone who read communist literature could be expelled.

They judged that independence would be difficult to achieve through the provisional government's diplomatic focus or limited armed struggle alone.

He began to take an interest in the Soviet Revolution in Russia by secretly reading communist books.

--- p.57~58

The activities of the members of the Overthrow Imperialism League were known beyond Jilin and even reached Seoul and Shanghai, and people said, “A new wind is blowing in Jilin.”

“If you want to fight for independence, you have to go to Jilin,” he said.

This wind was called the 'Jilin Wind' and spread widely.

Among the young men who came to see Kim Seong-ju after hearing this rumor, Cha Gwang-su and Kim Hyeok later became his closest comrades.

Around this time, Kim Seong-ju was also called 'Kim Il-sung' or 'Hanbyeol'.

In October 1928, Kim Seong-ju organized a demonstration against the construction of the Gilhoe Line railroad and issued a statement condemning it.

The protests soon spread throughout Manchuria, and Kim Seong-ju expanded them into a movement to boycott Japanese goods.

As a result, the Chinese people resisted by taking Japanese products out of Japanese stores and throwing them into the Songhua River or burning them.

The protests against the construction of the Gilhoe Line railroad and the boycott of Japanese goods, which lasted for about 40 days from October to November 1928, were the first mass anti-Japanese struggles led by Kim Seong-ju.

--- p.62~63

On December 16, 1931, about 40 young fighters, including Kim Il-sung, Cha Gwang-su, and Lee Gwang, gathered in Myeongwol District, Yanji County and began preparations to establish the Anti-Japanese People's Guerrilla Force.

The Anti-Japanese People's Guerrilla Army was a revolutionary army composed of children of workers and peasants, fighting for the liberation of the fatherland and the freedom and happiness of the people.

They planned to seize Japanese weapons, arm themselves, and establish a liberated area through guerrilla warfare, then install a revolutionary government, schools, hospitals, weapons repair shops, and publishing houses within it.

It was decided to form a semi-guerrilla zone by placing revolutionary rural areas around the guerrilla zone.

In each county of Dongman, small guerrilla groups of 1 to 20 people were organized, and in early March 1932, in Sosaha, Ando, a youth guerrilla group of 18 people directly commanded by Kim Il-sung was formed.

Afterwards, guerrilla organizations continued to form in various places.

For the young Koreans who had to just beat their chests and cry while losing their families to the Japanese army right before their eyes, taking up real guns and fighting the Japanese was a fervent wish and hope.

--- p.77~78

Even as Chinese and Korean independence activists fled to China immediately after the Manchurian Incident in 1931, Kim Il-sung raised the slogan, “Armed with Arms,” and set out to establish the Anti-Japanese People’s Guerrilla Army.

In 1934, when the Japanese surrounded and pressured the guerrilla base, he responded with a surprise attack from behind rather than a passive defense.

He responded to the unprecedented and vicious suppression known as Operation Weigong by further expanding the guerrilla zone, and eventually voluntarily disbanded the guerrilla zone, thereby breaking away from defensive battles and launching an expedition to northern Manchuria.

As a result, the flag of the Korean People's Revolutionary Army was able to fly even more vigorously.

The confidence in this offensive strategy stems from the people's independent line, which is the starting point of Kim Il-sung's ideology.

In the mid-1930s, while many patriotic leaders who supported the independence movement remained silent or defected, Kim Il-sung found hope among the people.

As the oppression of the Japanese became more severe, the people, who had lost everything, had no choice but to engage in an even more fierce anti-Japanese struggle.

His policy was to believe in the people and achieve independence through their power.

--- p.115~116

But he was moved by the sight of the people rising up with guns and clubs in the midst of such tragedy.

In particular, the scene where women took part in the anti-Japanese struggle left a strong impression.

Kim Il-sung wanted to create a play featuring such women as the main characters.

(…) The curtain finally rose on the play.

The atrocities of the Japanese that turned the entire village into a sea of blood, the lamentations of a family that lost their husbands and fathers, and the images of mothers and children who were reborn as fighters unfolded on stage.

The audience wept, and one old man jumped onto the stage and struck the forehead of the actor playing the leader of the punitive expedition with a long stick.

As the performance ended, applause poured in.

“Let us also join the fight against the Japanese!” The young men petitioned to enlist, and the villagers enjoyed the play by lamplight until past midnight.

The performance of “Sea of Blood” transformed the blind mountain villagers into supporters and direct participants in the anti-Japanese struggle.

When a revolutionary battlefield survey team visited Manjiang some 20 years later, the residents vividly remembered the names of the characters, the plot, and even the dialogue.

The shock and impression that the performance of “Sea of Blood” left on the villagers at the time was deep.

--- p.141~142

The Battle of Pochonbo was an ordinary raid without aircraft or tanks, but the way it unfolded demonstrated the essence of guerrilla warfare.

It was a three-dimensional battle in which all elements were meticulously combined, including target setting, timing selection, surprise attacks, psychological shock through arson, and even political propaganda.

(…) 1937 was a time when colonial rule was further strengthened and the domestic national movement was suppressed and stagnant before and after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War.

The Battle of Pochonbo, which broke out at this time, rekindled the spark of national liberation.

“The Korean people are alive and not dead.

“If we fight against the Japanese, we can win.” The flames of Pochonbo spread this conviction throughout the country.

The guerrillas, having finished the battle, escaped with clubs.

The members each put a handful of soil from their homeland into their backpacks.

A handful of soil from the motherland was like a heart to the guerrillas.

--- p.174~175

The column advancing to the fatherland left Begibong Peak and continued to march until it finally reached Samjiyeon Pond.

In that place where clear, blue waves rippled, the team members rushed to drink water and quench their thirst.

Azaleas were in full bloom along the pond, and their reflections were clearly visible on the still water.

The scenery above and below the water, reality and reflection mixed together, was truly breathtaking.

The members were so immersed in the peace and joy they felt in the embrace of their homeland that they felt like building a hut and staying there.

The unique alpine atmosphere of Baekdu Plain and the peaceful harmony of the fields were a beauty of the motherland that could not be exchanged for a billion dollars.

But that beauty soon gave way to the sorrow of colonial reality.

Facing the majestic mountains and rivers, the members felt anew how precious our people's land had been taken away by the Japanese.

--- p.208~209

The Korean People's Revolutionary Army Command held meetings of the organization leaders of the Fatherland Restoration Association at a secret temporary base on Sangdansan Mountain in Yeonsa-myeon, Musan County in July 1944 and June 1945.

At this meeting, it was decided to expand the Fatherland Restoration Movement nationwide to further expand national unity.

At that time, various independence movement forces at home and abroad were also paying attention to the activities of the Korean People's Revolutionary Army.

Kim Gu of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea in Chongqing attempted to establish contact by sending a liaison officer and also appealed to Koreans living in the United States to raise funds to support the Korean People's Revolutionary Army.

Yeo Un-hyeong also sought cooperation from 1944, and the Korean Independence Alliance and the Korean Volunteer Army also showed signs of cooperation.

In this way, the Korean People's Revolutionary Army emerged as more than just a simple armed force, becoming a central axis where the hopes of the Korean people gathered and where independence movement forces at home and abroad cooperated.

--- p.246~247

On August 9, 1945, when the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and entered the war, Kim Il-sung also gave the order for a general attack to liberate the fatherland.

The Korean People's Revolutionary Army, together with the Soviet Army, entered the great battle for national liberation by eliminating the Japanese army.

The Soviet Army was impressed by the Korean People's Revolutionary Army's sacrifice of their lives for the liberation of the nation and the people.

The greatest task of the fatherland liberation operation was to break through the border fortresses along the Tumen River.

Japan boasted of the Gyeongheung, Najin, and Unggi fortresses, as well as the Hunchun and Dongheungjin fortresses in Manchuria, as "impregnable defense lines."

If the Allied Forces failed to break through this defensive line, the victory of the general offensive operation could not be guaranteed.

(…) The fortress of Unggi at the mouth of the Tuman River was a key military stronghold located between Gyeongheung and Najin, and if it fell, both fortresses would be threatened.

Oh Baek-ryong's small unit crossed the Tumen River by surprise in heavy rain, attacked a Japanese military post, and liberated the Tori area.

They watched the police station burning before reinforcements could even approach and withdrew.

At the same time, a surprise attack was successful at Nambyeol-ri and Dongheungjin in Hunchun, Manchuria, causing confusion in the Japanese defense network and exposing weaknesses in the defense line.

With the border fortresses, which were considered impregnable, being taken over in one fell swoop, a breakthrough for the liberation of the fatherland was opened.

This means that the Korean People's Revolutionary Army took the lead in breaking through the decisive battles of the war against Japan and took the lead in liberation.

--- p.255~256

Even after Japan's surrender on August 15, 1945, the Korean People's Revolutionary Army continued military operations.

(…) Along with this, the Fatherland Restoration Association, the National Resistance Organization, and the people rose up in armed uprisings in various places to help the military advance.

At the heart of the people's armed organizations, which have various names such as the Red Guard, Security Corps, Autonomous Corps, and Self-Defense Corps, there have always been members of revolutionary organizations.

(…) According to statistics, excluding South and North Hamgyong Provinces, which had already been liberated by the Korean People's Revolutionary Army and the Soviet Army, armed uprisings and demonstrations occurred in over 1,000 places across the country from August 13 to 23, effectively paralyzing the Japanese ruling system.

The people organized people's committees in each liberated area and created a new order.

For example, in South Hamgyong Province, people's committees were formed in three cities, 16 counties, and 129 townships by the end of August.

In this way, our people began to practice building an independent and autonomous nation.

The liberation of our people was achieved through the power of the Korean People's Revolutionary Army and the people themselves, under favorable conditions in which the Sino-Soviet Allied Forces defeated the Japanese Kwantung Army.

The final offensive operation, the people's active resistance, and the rear strike operation carried out under Kim Il-sung's orders were the driving force behind the collapse of the Japanese colonial rule and the achievement of liberation.

--- p.268~272

Publisher's Review

Asking questions to establish a correct national history!

“Did we become independent on our own, or were we liberated by foreign powers?”

There are three main perspectives on the process of our country's liberation.

First, the American-centric perspective that "the Korean Peninsula was liberated when the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Japan and forced its surrender," second, the compromise interpretation that "liberation was achieved through the Allied victory in the war and independence movements at home and abroad," and third, the nationalist perspective that "liberation was achieved by our people themselves."

Among these, the perspective of the national subject was rarely discussed in history books from the South after the division because it had to acknowledge the achievements of the socialist independence movement.

As a result, the pro-Japanese vested interests that have continued since the Japanese colonial period have downplayed and distorted the significance of the independence movement in the history of liberation.

The author says that records of the North's independence movement, which we were unaware of, are essential for a balanced understanding of the history of liberation.

The question of whether we have achieved liberation through our own strength, rather than through the power of a powerful nation, is the starting point of this book and the most fundamental question the author poses to the world.

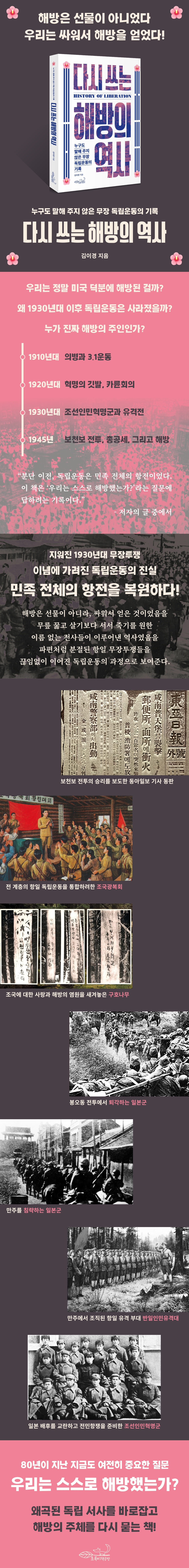

In search of the truth about the armed struggle of the 1930s

Stories of those who sacrificed their lives for the liberation of their country

It is difficult to find records of armed struggles after the 1930s in the history of liberation.

This book traces the footsteps of armed independence fighters fighting against Japanese colonial rule until just before liberation, tracing the whereabouts and activities of the independence army after the Battle of Bongodong and the Battle of Cheongsanri.

We examine the process by which the spark of national resistance that began with the March 1st Movement spread into armed struggle, and, through division and unification, developed into an organized and strategic war for independence.

In particular, the gathering of young revolutionaries that began in Jilin, the establishment of a new course through the Kalun Conference, the guerrilla warfare with the people, and the fierce anti-Japanese armed struggle centered around Mt. Baekdu are vividly restored through various materials.

It also deals with the history of armed struggle centered on Kim Il-sung, which has been intentionally excluded or distorted in the history of the South, as an important axis.

It sheds light on the 19-year journey of the youth group organized by Kim Il-sung, who began contributing to the independence of the fatherland during their teenage years at Hwaseong High School, and their anti-Japanese armed struggle that continued until 1945 with consistent strategies and tactics.

This is not simply to defend the North's view of history or the legitimacy of its socialist regime, but rather a necessary process for properly understanding one axis of our independence movement history that is clearly recorded in Japanese records.

Commemorating the 80th anniversary of liberation

Re-recording the history of the independence movement between the South and the North

Knowing history correctly is not just an academic pursuit; it is a matter that determines the direction of the future.

As we mark the 80th anniversary of liberation, looking back on the history of the independence movement between the South and the North is not just a matter of restoring the past, but also a task of correcting today's perception of history.

This book will serve as a reliable guide for readers seeking to correctly understand modern history since liberation, teachers in the field of history education, and all those seeking to bridge the gap in perspectives between the South and the North.

“Did we become independent on our own, or were we liberated by foreign powers?”

There are three main perspectives on the process of our country's liberation.

First, the American-centric perspective that "the Korean Peninsula was liberated when the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Japan and forced its surrender," second, the compromise interpretation that "liberation was achieved through the Allied victory in the war and independence movements at home and abroad," and third, the nationalist perspective that "liberation was achieved by our people themselves."

Among these, the perspective of the national subject was rarely discussed in history books from the South after the division because it had to acknowledge the achievements of the socialist independence movement.

As a result, the pro-Japanese vested interests that have continued since the Japanese colonial period have downplayed and distorted the significance of the independence movement in the history of liberation.

The author says that records of the North's independence movement, which we were unaware of, are essential for a balanced understanding of the history of liberation.

The question of whether we have achieved liberation through our own strength, rather than through the power of a powerful nation, is the starting point of this book and the most fundamental question the author poses to the world.

In search of the truth about the armed struggle of the 1930s

Stories of those who sacrificed their lives for the liberation of their country

It is difficult to find records of armed struggles after the 1930s in the history of liberation.

This book traces the footsteps of armed independence fighters fighting against Japanese colonial rule until just before liberation, tracing the whereabouts and activities of the independence army after the Battle of Bongodong and the Battle of Cheongsanri.

We examine the process by which the spark of national resistance that began with the March 1st Movement spread into armed struggle, and, through division and unification, developed into an organized and strategic war for independence.

In particular, the gathering of young revolutionaries that began in Jilin, the establishment of a new course through the Kalun Conference, the guerrilla warfare with the people, and the fierce anti-Japanese armed struggle centered around Mt. Baekdu are vividly restored through various materials.

It also deals with the history of armed struggle centered on Kim Il-sung, which has been intentionally excluded or distorted in the history of the South, as an important axis.

It sheds light on the 19-year journey of the youth group organized by Kim Il-sung, who began contributing to the independence of the fatherland during their teenage years at Hwaseong High School, and their anti-Japanese armed struggle that continued until 1945 with consistent strategies and tactics.

This is not simply to defend the North's view of history or the legitimacy of its socialist regime, but rather a necessary process for properly understanding one axis of our independence movement history that is clearly recorded in Japanese records.

Commemorating the 80th anniversary of liberation

Re-recording the history of the independence movement between the South and the North

Knowing history correctly is not just an academic pursuit; it is a matter that determines the direction of the future.

As we mark the 80th anniversary of liberation, looking back on the history of the independence movement between the South and the North is not just a matter of restoring the past, but also a task of correcting today's perception of history.

This book will serve as a reliable guide for readers seeking to correctly understand modern history since liberation, teachers in the field of history education, and all those seeking to bridge the gap in perspectives between the South and the North.

GOODS SPECIFICS

- Date of issue: August 30, 2025

- Page count, weight, size: 272 pages | 356g | 141*205*17mm

- ISBN13: 9791199385337

- ISBN10: 1199385336

You may also like

카테고리

korean

korean

![ELLE 엘르 스페셜 에디션 A형 : 12월 [2025]](http://librairie.coreenne.fr/cdn/shop/files/b8e27a3de6c9538896439686c6b0e8fb.jpg?v=1766436872&width=3840)